Rose-Marie Dechaine and Martina Wiltschko (UBC)

Rose-Marie Dechaine and Martina Wiltschko (UBC)

Rose-Marie Dechaine and Martina Wiltschko (UBC)

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Dissolving Condition A<br />

<strong>Rose</strong>-<strong>Marie</strong> Déchaine & <strong>Martina</strong> <strong>Wiltschko</strong>; <strong>UBC</strong><br />

dechaine@interchange.ubc.ca; wmartina@interchange.ubc.ca<br />

1. The residue of Binding Theory: Condition A. Classical binding theory (Chomsky 1981) posits<br />

three binding conditions to account for the resolution of referential dependencies. While Conditions B<br />

<strong>and</strong> C have been argued to be the effect of independent factors -- see Burzio 1989 <strong>and</strong> Reinhart 1986<br />

respectively – Condition A still remains a primitive in the theory. The classical formulation of Condition<br />

A requires that “anaphors” be locally bound. In addition, it defines anaphors as including both reflexives<br />

<strong>and</strong> reciprocals. These definitions are problematic for two reasons.<br />

(i) local binding as a primitive: Most current analyses still posit local binding as a primitive: for<br />

example, Reinhart & Reul<strong>and</strong> 1993, Safir 2003 still retain a version of Condition A. Such approaches<br />

fail to account for the heterogeneity of reflexive expressions both within <strong>and</strong> across languages.<br />

(ii) stipulated parallelism between reflexives <strong>and</strong> reciprocals: Lebeaux (1983) observes that<br />

reciprocals occur in a wider range of environments than reflexives; this remains unexpected under the<br />

st<strong>and</strong>ard account.<br />

2. Proposal. We argue that just as Condition B <strong>and</strong> C effects are derivative, so too are Condition A<br />

effects. In particular, we propose that Condition A effects are accounted for if we assume that binding<br />

properties are in part determined by syntactic category. In particular, we adopt the D/φ/N- distinction as<br />

in (1) where D is an R-expression, φ a variable <strong>and</strong> N a nominal constant (Déchaine&<strong>Wiltschko</strong> 2002a).<br />

(1) [ DP [D] [ φP [φ] [ NP [N]]]<br />

We further propose that reflexives <strong>and</strong> reciprocals differ such that reflexives display structural variance<br />

<strong>and</strong> consequently local binding is derived in different ways. In contrast, we argue that reciprocals are<br />

always associated with a DP-structure due to the semantics of reciprocal construals.<br />

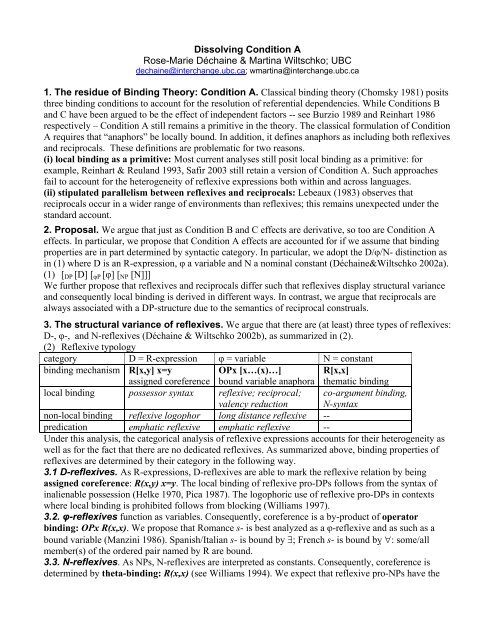

3. The structural variance of reflexives. We argue that there are (at least) three types of reflexives:<br />

D-, φ-, <strong>and</strong> N-reflexives (Déchaine & <strong>Wiltschko</strong> 2002b), as summarized in (2).<br />

(2) Reflexive typology<br />

category D = R-expression φ = variable N = constant<br />

binding mechanism R[x,y] x=y OPx [x…(x)…] R[x,x]<br />

assigned coreference bound variable anaphora thematic binding<br />

local binding possessor syntax reflexive; reciprocal; co-argument binding,<br />

valency reduction N-syntax<br />

non-local binding reflexive logophor long distance reflexive --<br />

predication emphatic reflexive emphatic reflexive --<br />

Under this analysis, the categorical analysis of reflexive expressions accounts for their heterogeneity as<br />

well as for the fact that there are no dedicated reflexives. As summarized above, binding properties of<br />

reflexives are determined by their category in the following way.<br />

3.1 D-reflexives. As R-expressions, D-reflexives are able to mark the reflexive relation by being<br />

assigned coreference: R(x,y) x=y. The local binding of reflexive pro-DPs follows from the syntax of<br />

inalienable possession (Helke 1970, Pica 1987). The logophoric use of reflexive pro-DPs in contexts<br />

where local binding is prohibited follows from blocking (Williams 1997).<br />

3.2. φ-reflexives function as variables. Consequently, coreference is a by-product of operator<br />

binding: OPx R(x,x). We propose that Romance s- is best analyzed as a φ-reflexive <strong>and</strong> as such as a<br />

bound variable (Manzini 1986). Spanish/Italian s- is bound by ∃; French s- is bound by ∀: some/all<br />

member(s) of the ordered pair named by R are bound.<br />

3.3. N-reflexives. As NPs, N-reflexives are interpreted as constants. Consequently, coreference is<br />

determined by theta-binding: R(x,x) (see Williams 1994). We expect that reflexive pro-NPs have the

distribution of N, e.g. the occurrence of English self in compounding. Languages which have noun<br />

incorporation also have incorporated reflexive pro-NPs; this a predictable by-product of their N-syntax.<br />

4. The structural invariance of reciprocals. Heim, Lasnik & May 1991 argue that a reciprocal<br />

construction involves at least 4 parts: a plural antecedent, a distributor, a reciprocator, <strong>and</strong> a predicate, as<br />

in (3).<br />

(3) a. The men saw each other.<br />

b. [ S [ NP [ NP the men i ] each 2 ] [ S e 1 [ VP [ NP e 2=VBL other] 3 [ VP saw e 3 ]]]]<br />

GROUP DISTRIBUTOR RECIPROCATOR PREDICATE<br />

In a similar vein we argue that the syntax of a reciprocal expression (defined as the linguistic element<br />

which marks the reciprocal relation, e.g. each other in English) derives from independently motivated<br />

properties. We claim that there is a transparent relation between the semantics <strong>and</strong> the syntax of<br />

reciprocals, such that the distributor corresponds to a syntactic D-position, the plural variable induced<br />

by the distributive operator corresponds to a syntactic φ-position, <strong>and</strong> the reciprocator (a kind of disjoint<br />

anaphor) corresponds to a syntactic N-position. This is illustrated in (4):<br />

(4) syntax/semantics mapping for reciprocals<br />

distributor D = distributor (derives effect of ∀)<br />

plural variable φ = plural variable (Déchaine & <strong>Wiltschko</strong> 2002)<br />

plurality is forced by distributor which in turn forces plural antecedent via<br />

agreement<br />

local disjointness N = reciprocator (a kind of disjoint anaphor; cf. Saxon 1984, 1986)<br />

Consequently, argument-type reciprocals are invariantly realized as DPs - language internally as well as<br />

cross-linguistically. We analyze apparent surface differences in the overt realization of reciprocal<br />

expressions as reflecting which part of the DP-structure is spelled out. We will show that this proposal<br />

solves some long-st<strong>and</strong>ing problems in the syntax <strong>and</strong> semantics of reciprocals.<br />

4.1. Non-parallelism between reflexives <strong>and</strong> reciprocals. Under our account the distributional<br />

differences between reflexives <strong>and</strong> reciprocals follows from two factors. First, reciprocals are always<br />

DPs whereas reflexives can be DPs, φPs or NPs. In addition, we argue that non-local binding of<br />

reciprocals is possible because there is no other way of expressing the reciprocal relation (i.e. there is no<br />

blocking). Conversely, the occurrence of reflexives in the same context is blocked by the existence of<br />

the more highly specified form his own (Williams 1994).<br />

Moreover, in languages that permit long-distance binding of reflexives, we observe the absence of<br />

long-distance reciprocals. We take this to reflect the fact that reciprocals are always evaluated w.r.t to<br />

the most accessible antecedent. Under the proposed analysis, this follows from the status of the<br />

reciprocator as a disjoint anaphor, which according to Saxon 1984, is always disjoint in reference from<br />

the most locally accessible antecedent.<br />

4.2. Absence of dedicated reciprocals. Our proposal further predicts that there are no dedicated<br />

reciprocals, which we take to be a welcome result, given the goal of the principles <strong>and</strong> parameters<br />

framework to get rid of construction specific notions. We observe that the elements which make up a<br />

reciprocal expression occur in non-reciprocal contexts. The syntactic analysis proposed here predicts<br />

that when the reciprocal construal is not forced, then the overt element(s) of the reciprocal expression<br />

are construed in terms of their inherent semantics. Thus, the distributor/D component is interpreted as a<br />

pure distributive operator in non-reciprocal contexts (e.g. in Madurese). The variable/φ component is<br />

interpreted as a pure variable in non-reciprocal contexts (e.g. Romance se). The reciprocator/N<br />

component is interpreted as a pure disjoint anaphor in non-reciprocal contexts (e.g. Plains Cree).<br />

5. Consequences. In this talk we show that just like Condition B <strong>and</strong> C can be derived, so can<br />

Condition A. Consequently, with this analysis in place we can dispense with binding theory as a separate<br />

module of grammar. This is a welcome result given the general goals of recent theorizing (i.e. the<br />

minimalist program).