47 - SC Judicial Department

47 - SC Judicial Department

47 - SC Judicial Department

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

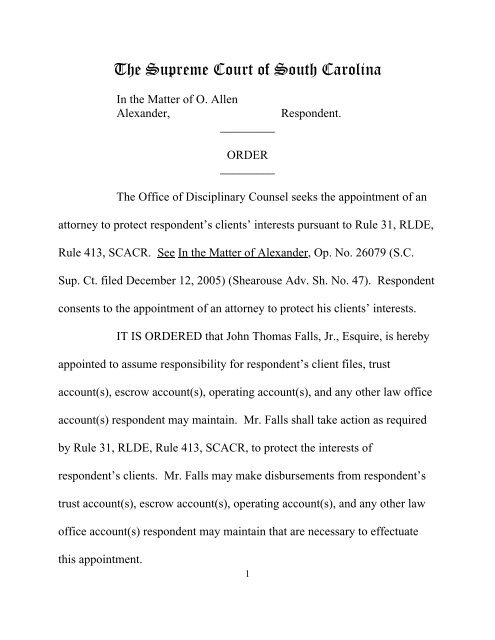

The Supreme Court of South Carolina<br />

In the Matter of O. Allen <br />

Alexander,<br />

_________<br />

Respondent. <br />

ORDER<br />

_________<br />

The Office of Disciplinary Counsel seeks the appointment of an<br />

attorney to protect respondent’s clients’ interests pursuant to Rule 31, RLDE,<br />

Rule 413, <strong>SC</strong>ACR. See In the Matter of Alexander, Op. No. 26079 (S.C.<br />

Sup. Ct. filed December 12, 2005) (Shearouse Adv. Sh. No. <strong>47</strong>). Respondent<br />

consents to the appointment of an attorney to protect his clients’ interests.<br />

IT IS ORDERED that John Thomas Falls, Jr., Esquire, is hereby<br />

appointed to assume responsibility for respondent’s client files, trust<br />

account(s), escrow account(s), operating account(s), and any other law office<br />

account(s) respondent may maintain. Mr. Falls shall take action as required<br />

by Rule 31, RLDE, Rule 413, <strong>SC</strong>ACR, to protect the interests of<br />

respondent’s clients. Mr. Falls may make disbursements from respondent’s<br />

trust account(s), escrow account(s), operating account(s), and any other law<br />

office account(s) respondent may maintain that are necessary to effectuate<br />

this appointment.<br />

1

This Order, when served on any bank or other financial <br />

institution maintaining trust, escrow and/or operating accounts of respondent,<br />

shall serve as an injunction to prevent respondent from making withdrawals<br />

from the account(s) and shall further serve as notice to the bank or other<br />

financial institution that John Thomas Falls, Jr., Esquire, has been duly<br />

appointed by this Court.<br />

Finally, this Order, when served on any office of the United<br />

States Postal Service, shall serve as notice that John Thomas Falls, Jr.,<br />

Esquire, has been duly appointed by this Court and has the authority to<br />

receive respondent's mail and the authority to direct that respondent’s mail be<br />

delivered to Mr. Falls’ office.<br />

This appointment shall be for a period of no longer than nine<br />

months unless request is made to this Court for an extension.<br />

s/Jean H. Toal<br />

FOR THE COURT<br />

C.J.<br />

Columbia, South Carolina<br />

December 12, 2005<br />

2

The Supreme Court of South Carolina<br />

In the Matter of Craig J. <br />

Poff,<br />

_________<br />

Respondent. <br />

ORDER<br />

_________<br />

The Office of Disciplinary Counsel seeks the appointment of an<br />

attorney to protect respondent’s clients’ interests pursuant to Rule 31, RLDE,<br />

Rule 413, <strong>SC</strong>ACR. See In the Matter of Poff, Op. No. 26080 (S.C. Sup. Ct.<br />

filed December 12, 2005) (Shearouse Adv. Sh. No. <strong>47</strong>). Respondent<br />

consents to the appointment of an attorney to protect his clients’ interests.<br />

IT IS ORDERED that Anthony O’Neil Dore, Esquire, is hereby<br />

appointed to assume responsibility for respondent’s client files, trust<br />

account(s), escrow account(s), operating account(s), and any other law office<br />

account(s) respondent may maintain. Mr. Dore shall take action as required<br />

by Rule 31, RLDE, Rule 413, <strong>SC</strong>ACR, to protect the interests of<br />

respondent’s clients. Mr. Dore may make disbursements from respondent’s<br />

trust account(s), escrow account(s), operating account(s), and any other law<br />

office account(s) respondent may maintain that are necessary to effectuate<br />

this appointment.<br />

3

This Order, when served on any bank or other financial <br />

institution maintaining trust, escrow and/or operating accounts of respondent,<br />

shall serve as an injunction to prevent respondent from making withdrawals<br />

from the account(s) and shall further serve as notice to the bank or other<br />

financial institution that Anthony O’Neil Dore, Esquire, has been duly<br />

appointed by this Court.<br />

Finally, this Order, when served on any office of the United<br />

States Postal Service, shall serve as notice that Anthony O’Neil Dore,<br />

Esquire, has been duly appointed by this Court and has the authority to<br />

receive respondent's mail and the authority to direct that respondent’s mail be<br />

delivered to Mr. Dore’s office.<br />

This appointment shall be for a period of no longer than nine<br />

months unless request is made to this Court for an extension.<br />

s/Jean H. Toal<br />

FOR THE COURT<br />

C.J.<br />

Columbia, South Carolina<br />

December 12, 2005<br />

4

OPINIONS <br />

OF <br />

THE SUPREME COURT <br />

AND <br />

COURT OF APPEALS <br />

OF<br />

SOUTH CAROLINA <br />

ADVANCE SHEET NO. <strong>47</strong><br />

December 12, 2005 <br />

Daniel E. Shearouse, Clerk<br />

Columbia, South Carolina <br />

www.sccourts.org <br />

5

CONTENTS<br />

THE SUPREME COURT OF SOUTH CAROLINA<br />

PUBLISHED OPINIONS AND ORDERS<br />

Page<br />

26079 - In the Matter of O. Allen Alexander 19<br />

26080 - In the Matter of Craig J. Poff 23<br />

UNPUBLISHED OPINIONS<br />

2005-MO-058 - Capricia Hampton v. State<br />

(Saluda County - Judge J. Michael Baxley and Judge James R.<br />

Barber, III)<br />

2005-MO-059 - In Re: Paul D. deHolczer<br />

(Dorchester County - Judge J. Michael Baxley)<br />

PETITIONS - UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT<br />

2005-OR-00357 - Donald J. Strable v. State<br />

Pending <br />

25991 - Gay Ellen Coon v. James Moore Coon Pending <br />

PETITIONS FOR REHEARING <br />

26022 - Strategic Resources Co., et al. v. BCS Life Insurance Co., et al. Pending <br />

26035 - Linda Gail Marcum v. Donald Mayon Bowden, et al. Pending <br />

26036 - Rudolph Barnes v. Cohen Dry Wall Pending <br />

26050 - James Simmons v. Mark Lift Industries, Inc., et al. Denied 12/12/05 <br />

2005-MO-052 - Kimberly Dunham v. Michael Coffey<br />

Pending <br />

6

THE SOUTH CAROLINA COURT OF APPEALS<br />

PUBLISHED OPINIONS<br />

Page<br />

4054-John E. Cooke and Barbara Cooke v. Palmetto Health Alliance 27<br />

d/b/a Palmetto Richland Memorial Hospital and Latisha C. Corley<br />

4055-Richard Aiken v. World Finance Corporation of South Carolina and 34<br />

World Acceptance Corporation<br />

4056-Timothy Jackson v. City of Abbeville, Riley’s BP, and Angela McCurry 42<br />

4057-Southern Glass & Plastics Co. v. Angela Duke 50<br />

4058-The State v. Kelvin R. Williams 60<br />

4059-Tawanda Simpson v. World Finance Corporation of South Carolina 67<br />

and World Acceptance Corporation<br />

UNPUBLISHED OPINIONS<br />

2005-UP-606-The State v. Christopher Dale Stepp<br />

(Greenville, Judge Larry R. Patterson)<br />

2005-UP-607-The State v. Dale Bruce Jenkins<br />

(Georgetown, Judge Paula H. Thomas)<br />

2005-UP-608-The State v. Isiah James, Jr.<br />

(Sumter, Judge Howard P. King)<br />

2005-UP-609-The State v. John Wallace Hayward<br />

(Richland, Judge Reginald I. Lloyd)<br />

2005-UP-610-The State v. Tammy Renee Jones<br />

(Spartanburg, Judge J. Derham Cole)<br />

2005-UP-611-The State v. Amy Hutto<br />

(Lexington, Judge Clifton Newman)<br />

7

2005-UP-612-The State v. Darrin Bellinger<br />

(Barnwell, Judge James C. Williams, Jr.)<br />

2005-UP-613-David Browder v. Ross Marine et al.<br />

(Charleston, Judge R. Markeley Dennis, Jr.)<br />

2005-UP-614-Sandra Bush, Employee v. South Carolina <strong>Department</strong> of<br />

Corrections, Employer, and State Accident Fund, Carrier<br />

(Dorchester, Judge James C. Williams, Jr.)<br />

2005-UP-615-The State v. Leonard A. Carter<br />

(Florence, Judge Clifton Newman)<br />

2005-UP-616-The State v. Heather R. Herring<br />

(Dorchester, Judge James C. Williams, Jr.)<br />

2005-UP-617-The Gatherings Horizontal Property Regime v. Bobby S. Williams<br />

(Beaufort, Judge Curtis L. Coltrane)<br />

PETITIONS FOR REHEARING<br />

4026-Wogan v. Kunze<br />

Pending<br />

4030-State v. Mekler Pending<br />

4034-Brown v. Greenwood Mills Inc.<br />

Pending<br />

4036-State v. Pichardo & Reyes Pending<br />

4037-Eagle Cont. v. County of Newberry et al.<br />

4039-Shuler v. Gregory Electric et al.<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

4040-Commander Healthcare v. <strong>SC</strong>DHEC Pending<br />

4041-Bessinger v. BI-LO<br />

Pending<br />

2005-UP-535-Tindall v. H&S Homes Pending<br />

2005-UP-539-Tharington v. Votor<br />

2005-UP-540-Fair et al. v. Gary Realty et al.<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

8

2005-UP-543-Jamrok v. Rogers et al.<br />

2005-UP-549-Jacobs v. Jackson<br />

2005-UP-574-State v. T. Phillips<br />

2005-UP-577-Pallanck et al. v. Lemieux et al.<br />

2005-UP-580-Garrett v. Garrett<br />

2005-UP-585-Newberry Elec. v. City of Newberry<br />

2005-UP-586-State v. T. Pate<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

PETITIONS - SOUTH CAROLINA SUPREME COURT<br />

3780-Pope v. Gordon<br />

3787-State v. Horton<br />

3809-State v. Belviso<br />

3821-Venture Engineering v. Tishman<br />

3825-Messer v. Messer<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

3832-Carter v. U<strong>SC</strong> Pending<br />

3836-State v. Gillian<br />

Pending<br />

3842-State v. Gonzales Pending<br />

3849-Clear Channel Outdoor v. City of Myrtle Beach<br />

3852-Holroyd v. Requa<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

3853-McClain v. Pactiv Corp. Pending<br />

3855-State v. Slater Pending<br />

3857-Key Corporate v. County of Beaufort<br />

Pending<br />

9

3858-O’Braitis v. O’Braitis<br />

Pending<br />

3860-State v. Lee Pending<br />

3861-Grant v. Grant Textiles et al.<br />

Pending<br />

3863-Burgess v. Nationwide Pending<br />

3864-State v. Weaver Pending<br />

3865-DuRant v. <strong>SC</strong>DHEC et al<br />

Pending<br />

3866-State v. Dunbar Pending<br />

3871-Cannon v. <strong>SC</strong>DPPPS Pending<br />

3877-B&A Development v. Georgetown Cty.<br />

3879-Doe v. Marion (Graf)<br />

3883-Shadwell v. Craigie<br />

3890-State v. Broaddus<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

3900-State v. Wood Pending<br />

3903-Montgomery v. CSX Transportation<br />

Pending<br />

3906-State v. James Pending<br />

3910-State v. Guillebeaux<br />

3911-Stoddard v. Riddle<br />

3912-State v. Brown<br />

3914-Knox v. Greenville Hospital<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

3917-State v. Hubner Pending<br />

3918-State v. N. Mitchell<br />

Pending<br />

10

3919-Mulherin et al. v. Cl. Timeshare et al.<br />

Pending<br />

3926-Brenco v. <strong>SC</strong>DOT Pending<br />

3928-Cowden Enterprises v. East Coast<br />

3929-Coakley v. Horace Mann<br />

3935-Collins Entertainment v. White<br />

3936-Rife v. Hitachi Construction et al.<br />

3938-State v. E. Yarborough<br />

3939-State v. R. Johnson<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

3940-State v. H. Fletcher Pending<br />

3943-Arnal v. Arnal Pending<br />

39<strong>47</strong>-Chassereau v. Global-Sun Pools Pending<br />

3949-Liberty Mutual v. S.C. Second Injury Fund<br />

Pending<br />

3950-State v. Passmore Pending<br />

3952-State v. K. Miller<br />

3954-Nationwide Mutual Ins. v. Erwood<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

3955-State v. D. Staten Pending<br />

3963-McMillan v. <strong>SC</strong> Dep’t of Agriculture<br />

3965-State v. McCall<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

3966-Lanier v. Lanier Pending<br />

3967-State v. A. Zeigler<br />

3968-Abu-Shawareb v. S.C. State University<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

11

3970-State v. C. Davis Pending<br />

3971-State v. Wallace<br />

3976-Mackela v. Bentley<br />

3977-Ex parte: USAA In Re: Smith v. Moore)<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

3978-State v. K. Roach Pending<br />

3981-Doe v. <strong>SC</strong>DDSN et al.<br />

3983-State v. D. Young<br />

3984-Martasin v. Hilton Head<br />

3985-Brewer v. Stokes Kia<br />

3988-Murphy v. Jefferson Pilot<br />

3989-State v. Tuffour<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

3993-Thomas v. Lutch (Stevens) Pending<br />

3994-Huffines Co. v. Lockhart<br />

Pending<br />

3995-Cole v. Raut Pending<br />

3996-Bass v. Isochem Pending<br />

3998-Anderson v. Buonforte Pending<br />

4000-Alexander v. Forklifts Unlimited<br />

4004-Historic Charleston v. Mallon<br />

4005-Waters v. Southern Farm Bureau<br />

4006-State v. B. Pinkard<br />

4014-State v. D. Wharton<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

12

4015-Collins Music Co. v. IGT<br />

Pending<br />

4020-Englert, Inc. v. LeafGuard USA, Inc. Pending<br />

4022-Widdicombe v. Tucker-Cales Pending<br />

2003-UP-642-State v. Moyers<br />

Pending<br />

2003-UP-716-State v. Perkins Pending<br />

2003-UP-757-State v. Johnson<br />

2004-UP-219-State v. Brewer<br />

2004-UP-271-Hilton Head v. Bergman<br />

2004-UP-366-Armstong v. Food Lion<br />

2004-UP-381-Crawford v. Crawford<br />

2004-UP-394-State v. Daniels<br />

2004-UP-409-State v. Moyers<br />

2004-UP-422-State v. Durant<br />

2004-UP-427-State v. Rogers<br />

2004-UP-430-Johnson v. S.C. Dep’t of Probation<br />

2004-UP-439-State v. Bennett<br />

2004-UP-460-State v. Meggs<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

2004-UP-482-Wachovia Bank v. Winona Grain Co. Pending<br />

2004-UP-485-State v. Rayfield<br />

2004-UP-487-State v. Burnett<br />

2004-UP-496-Skinner v. Trident Medical<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

13

2004-UP-500-Dunbar v. Johnson<br />

2004-UP-504-Browning v. Bi-Lo, Inc.<br />

2004-UP-505-Calhoun v. Marlboro Cty. School<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

2004-UP-513-BB&T v. Taylor Pending<br />

2004-UP-517-State v. Grant Pending<br />

2004-UP-520-Babb v. Thompson et al (5)<br />

2004-UP-521-Davis et al. v. Dacus<br />

2004-UP-537-Reliford v. Mitsubishi Motors<br />

2004-UP-540-<strong>SC</strong>DSS v. Martin<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

2004-UP-542-Geathers v. 3V, Inc. Pending<br />

2004-UP-550-Lee v. Bunch<br />

2004-UP-554-Fici v. Koon<br />

2004-UP-555-Rogers v. Griffith<br />

2004-UP-556-Mims v. Meyers<br />

2004-UP-560-State v. Garrard<br />

2004-UP-596-State v. Anderson<br />

2004-UP-598-Anchor Bank v. Babb<br />

2004-UP-600-McKinney v. McKinney<br />

2004-UP-605-Moring v. Moring<br />

2004-UP-606-Walker Investment v. Carolina First<br />

2004-UP-607-State v. Randolph<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

14

2004-UP-609-Davis v. Nationwide Mutual Pending<br />

2004-UP-610-Owenby v. Kiesau et al. Pending<br />

2004-UP-613-Flanary v. Flanary<br />

2004-UP-617-Raysor v. State<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

2004-UP-632-State v. Ford Pending<br />

2004-UP-635-Simpson v. Omnova Solutions<br />

2004-UP-650-Garrett v. Est. of Jerry Marsh<br />

2004-UP-653-State v. R. Blanding<br />

2004-UP-654-State v. Chancy<br />

2004-UP-657-<strong>SC</strong>DSS v. Cannon<br />

2004-UP-658-State v. Young<br />

2005-UP-001-Hill v. Marsh et al.<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

2005-UP-002-Lowe v. Lowe Pending<br />

2005-UP-014-Dodd v. Exide Battery Corp. et al.<br />

2005-UP-016-Averette v. Browning<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

2005-UP-018-State v. Byers Pending<br />

2005-UP-022-Ex parte Dunagin<br />

Pending<br />

2005-UP-023-Cantrell v. <strong>SC</strong>DPS Pending<br />

2005-UP-039-Keels v. Poston<br />

Pending<br />

2005-UP-046-CCDSS v. Grant Pending<br />

2005-UP-054-Reliford v. Sussman<br />

Pending<br />

15

2005-UP-058-Johnson v. Fort Mill Chrysler Pending<br />

2005-UP-113-McCallum v. Beaufort Co. Sch. Dt.<br />

2005-UP-115-Toner v. <strong>SC</strong> Employment Sec. Comm’n<br />

2005-UP-116-S.C. Farm Bureau v. Hawkins<br />

2005-UP-122-State v. K. Sowell<br />

2005-UP-124-Norris v. Allstate Ins. Co.<br />

2005-UP-128-Discount Auto Center v. Jonas<br />

2005-UP-130-Gadson v. ECO Services<br />

2005-UP-138-N. Charleston Sewer v. Berkeley County<br />

2005-UP-139-Smith v. Dockside Association<br />

2005-UP-149-Kosich v. Decker Industries, Inc.<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

2005-UP-152-State v. T. Davis Pending<br />

2005-UP-160-Smiley v. <strong>SC</strong>DHEC/OCRM Pending<br />

2005-UP-163-State v. L. Staten<br />

2005-UP-165-Long v. Long<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

2005-UP-170-State v. Wilbanks Pending<br />

2005-UP-171-GB&S Corp. v. Cnty. of Florence et al.<br />

2005-UP-173-DiMarco v. DiMarco<br />

2005-UP-174-Suber v. Suber<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

2005-UP-188-State v. T. Zeigler Pending<br />

2005-UP-192-Mathias v. Rural Comm. Ins. Co. Pending<br />

16

2005-UP-195-Babb v. Floyd<br />

Pending<br />

2005-UP-197-State v. L. Cowan Pending<br />

2005-UP-200-Cooper v. Permanent General Pending<br />

2005-UP-216-Hiott v. Kelly et al.<br />

2005-UP-219-Ralphs v. Trexler (Nordstrom)<br />

2005-UP-222-State v. E. Rieb<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

2005-UP-224-Dallas et al. v. Todd et al. Pending<br />

2005-UP-256-State v. T. Edwards<br />

Pending<br />

2005-UP-274-State v. R. Tyler Pending<br />

2005-UP-283-Hill v. Harbert<br />

2005-UP-296-State v. B. Jewell<br />

2005-UP-297-Shamrock Ent. v. The Beach Market<br />

2005-UP-298-Rosenblum v. Carbone et al.<br />

2005-UP-303-Bowen v. Bowen<br />

2005-UP-305-State v. Boseman<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

2005-UP-319-Powers v. Graham Pending<br />

2005-UP-337-Griffin v. White Oak Prop. Pending<br />

2005-UP-340-Hansson v. Scalise<br />

2005-UP-345-State v. B. Cantrell<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

2005-UP-348-State v. L. Stokes Pending<br />

2005-UP-354-Fleshman v. Trilogy & CarOrder<br />

Pending<br />

17

2005-UP-365-Maxwell v. <strong>SC</strong>DOT Pending<br />

2005-UP-373-State v. Summersett<br />

2005-UP-375-State v. V. Mathis<br />

2005-UP-422-Zepsa v. Randazzo<br />

2005-UP-425-Reid v. Maytag Corp.<br />

2005-UP-459-Seabrook v. Simmons<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

2005-UP-460-State v. McHam Pending<br />

2005-UP-<strong>47</strong>1-Whitworth v. Window World et al.<br />

2005-UP-<strong>47</strong>2-Roddey v. NationsWaste et al.<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

2005-UP-483-State v. A. Collins Pending<br />

2005-UP-506-Dabbs v. Davis et al.<br />

2005-UP-519-Talley v. Jonas<br />

2005-UP-523-Ducworth v. Stubblefield<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

Pending<br />

18

THE STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA <br />

In The Supreme Court <br />

In the Matter of O. Allen<br />

Alexander,<br />

_________<br />

__________<br />

Respondent.<br />

Opinion No. 26079<br />

Submitted October 11, 2005 - Filed December 12, 2005<br />

__________<br />

INDEFINITE SUSPENSION<br />

_________<br />

Henry B. Richardson, Jr., Disciplinary Counsel, and Susan M.<br />

Johnston, Deputy Disciplinary Counsel, both of Columbia, for<br />

Office of Disciplinary Counsel.<br />

O. Allen Alexander, of Columbia, pro se.<br />

_________<br />

PER CURIAM: In this attorney disciplinary matter,<br />

respondent and the Office of Disciplinary Counsel (ODC) have entered<br />

into an Agreement for Discipline by Consent (Agreement) pursuant to<br />

Rule 21, RLDE, Rule 413, <strong>SC</strong>ACR. In the Agreement, respondent<br />

admits misconduct and consents to either a definite suspension not to<br />

exceed two years or an indefinite suspension. We accept the<br />

Agreement and indefinitely suspend respondent from the practice of<br />

law in this state. The facts, as set forth in the Agreement, are as<br />

follows.<br />

19

FACTS<br />

Matter I<br />

In October 2003, a client retained respondent to initiate<br />

post-divorce litigation. The client advised respondent that her exhusband<br />

travels frequently out of the country and she made respondent<br />

aware of his travel schedule. The client expressed concern regarding<br />

her ex-husband’s instability and her own safety. Despite apparent<br />

opportunities, the client’s ex-husband had not been served at the time<br />

the client filed her complaint on July 28, 2004.<br />

Matter II<br />

In February 2004, respondent ordered a transcript from a<br />

court reporter. The court reporter sent respondent more than ten<br />

statements requesting payment. As of the date of the Agreement,<br />

respondent had not paid the court reporter.<br />

Matter III<br />

Clients retained respondent to assist with a property<br />

damage claim on their automobile. Respondent accepted the settlement<br />

check on the condition he would send the insurance company title to<br />

the automobile. Respondent disbursed the monies but never sent the<br />

title.<br />

Matter IV<br />

Respondent was retained to proceed in a collection matter.<br />

Respondent accepted approximately $1,125.00 in fees and costs and<br />

then ignored all inquires by the client and has not completed his<br />

services to the client.<br />

20

Matter V<br />

A couple retained respondent to represent them in regard to<br />

a non-disclosure issue in a real estate transaction. Respondent accepted<br />

a retainer of approximately $2,030.00 but failed to complete the<br />

services and subsequently refused all contact with the couple. The<br />

couple filed a claim with the Resolution of Fee Disputes Board which<br />

awarded them $1,530.00. Respondent failed to refund the unearned fee<br />

as awarded.<br />

Matter VI<br />

A circuit court judge reported respondent had failed to<br />

appear in his court for several matters even though he had been<br />

scheduled and notified to appear. Respondent’s failures to appear were<br />

to the detriment of his clients. All of the judge’s attempts to contact<br />

respondent about his failure to appear were unsuccessful.<br />

__________<br />

Respondent has fully cooperated with ODC in connection<br />

with these matters.<br />

LAW<br />

Respondent admits that, by his misconduct, he has violated<br />

the following provisions of the Rules of Professional Conduct, Rule<br />

407, <strong>SC</strong>ACR: Rule 1.1 (lawyer shall provide competent<br />

representation); Rule 1.3 (lawyer shall act with reasonable diligence<br />

and promptness in representing a client); Rule 1.4 (lawyer shall keep a<br />

client reasonably informed about the status of a matter and promptly<br />

comply with reasonable requests for information)); Rule 1.5 (lawyer’s<br />

fee shall be reasonable); Rule 1.15 (lawyer shall promptly deliver any<br />

fees or property that a client or third person is entitled to receive);<br />

Rule 3.2 (lawyer shall make reasonable efforts to expedite litigation<br />

consistent with the interests of the client); Rule 8.4(a) (it is professional<br />

misconduct for lawyer to violate the Rules of Professional Conduct);<br />

and Rule 8.4(e) (it is professional misconduct for a lawyer to engage in<br />

21

conduct that is prejudicial to the administration of justice). 1 In<br />

addition, respondent admits his misconduct constitutes grounds for<br />

discipline under Rule 7, RLDE, of Rule 413, <strong>SC</strong>ACR, specifically Rule<br />

7(a)(1) (it shall be ground for discipline for lawyer to violate the Rules<br />

of Professional Conduct), Rule 7(a)(5) (it shall be ground for discipline<br />

for lawyer to engage in conduct tending to pollute the administration of<br />

justice), Rule 7(a)(6) (it shall be ground for discipline for lawyer to<br />

violate the oath of office taken upon admission to practice law in this<br />

state), and Rule 7(a)(10) (it shall be ground for discipline for lawyer to<br />

willfully fail to comply with a final decision of the Resolution of Fee<br />

Disputes Board).<br />

CONCLUSION<br />

We accept the Agreement for Discipline by Consent and<br />

indefinitely suspend respondent from the practice of law. ODC shall 1)<br />

determine the amount of restitution owed to respondent’s clients and<br />

others who have been harmed as a result of respondent’s misconduct<br />

and 2) institute a meaningful restitution plan. Within fifteen days of the<br />

date of this opinion, respondent shall surrender his certificate of<br />

admission to practice law in this state to the Clerk of Court and shall<br />

file an affidavit with the Clerk of Court showing that he has complied<br />

with Rule 30, RLDE, Rule 413, <strong>SC</strong>ACR. 2<br />

INDEFINITE SUSPENSION.<br />

TOAL, C.J., MOORE, WALLER, BURNETT and<br />

PLEICONES, JJ., concur.<br />

1<br />

Respondent’s misconduct occurred before the effective<br />

date of the Amendments to the Rules of Professional Conduct. See<br />

Court Order dated June 20, 2005. The Rules cited in this opinion are<br />

those which were in effect at the time of respondent’s misconduct.<br />

2 The parties agreed to the appointment of an attorney to<br />

protect respondent’s clients’ interests. By separate order, the Court will<br />

appoint an attorney to protect respondent’s clients’ interests.<br />

22

THE STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA <br />

In The Supreme Court <br />

_________<br />

In the Matter of Craig J. Poff,<br />

__________<br />

Respondent.<br />

Opinion No. 26080<br />

Submitted October 24, 2005 - Filed December 12, 2005<br />

__________<br />

DEFINITE SUSPENSION<br />

_________<br />

Henry B. Richardson, Jr., Disciplinary Counsel, and C. Tex<br />

Davis, Jr., Assistant Disciplinary Counsel, both of Columbia, for<br />

the Office of Disciplinary Counsel.<br />

Craig J. Poff, of Beaufort, pro se.<br />

_________<br />

PER CURIAM: In this attorney disciplinary matter,<br />

respondent and the Office of Disciplinary Counsel (ODC) have entered<br />

into an Agreement for Discipline by Consent (Agreement) pursuant to<br />

Rule 21, RLDE, Rule 413, <strong>SC</strong>ACR. In the Agreement, respondent<br />

admits misconduct and consents to the imposition of an admonition,<br />

public reprimand, or definite suspension not to exceed sixty (60) days.<br />

We accept the Agreement and definitely suspend respondent from the<br />

practice of law in this state for a sixty (60) day period. The facts, as set<br />

forth in the Agreement, are as follows.<br />

23

FACTS<br />

In or about May 2003, the complainant obtained a home<br />

equity line of credit from Navy Federal Credit Union (Navy Federal).<br />

She was told by Navy Federal that Don Young would be the closing<br />

attorney. Don Young is the owner of American Title & Abstract; he is<br />

not a licensed attorney.<br />

Respondent represents that, on the morning of May 12,<br />

2003, a member of Mr. Young’s office contacted him and asked if he<br />

could handle a closing in the afternoon. Respondent agreed to handle<br />

the closing. Respondent did not attend the closing; he represents he<br />

was unable to attend the closing at the scheduled time because he was<br />

in court on an unrelated matter.<br />

Because he was unable to attend the closing, respondent<br />

telephoned a staff member at American Title & Abstract, where the<br />

closing was to occur, and requested that the complainant postpone the<br />

closing until he could arrive. When the complainant indicated she did<br />

not want any delay, respondent instructed the staff member to let the<br />

complainant execute the closing documents and leave them for him to<br />

review. Respondent never spoke with the complainant prior to<br />

executing the closing documents; he was not present at the closing<br />

itself; and respondent did not speak with the complainant after the<br />

closing.<br />

Respondent represents he arrived at American Title &<br />

Abstract the following morning and, for the first time, reviewed the<br />

closing documents. Respondent asserts he spoke with a staff member<br />

at American Title & Abstract who stated that she had been present<br />

when the complainant executed the closing documents. The staff<br />

member provided respondent with the mortgage which the complainant<br />

had signed at the closing the day before. On page seven of the<br />

mortgage, the staff member verified to respondent that her own<br />

signature appeared on the line designated as Witness #1 and that she<br />

had personally observed the complainant execute the mortgage.<br />

24

Respondent admits he affixed his signature on the line<br />

designated as Witness #2 even though he had not been present for the<br />

closing and had not personally witnessed the complainant execute the<br />

mortgage. On page eight of the mortgage, respondent notarized the<br />

staff member’s statement that she, along with the other witness<br />

delineated on page seven (i.e., respondent), had witnessed the execution<br />

of the mortgage. Respondent admits this was a false statement as he<br />

was not personally present at the time the complainant executed the<br />

mortgage. He further admits he allowed the staff member to falsely<br />

swear before him as a Notary Public.<br />

Respondent admits that, after reviewing the mortgage and<br />

settlement statement, he returned all original documents to Navy<br />

Federal pursuant to Navy Federal’s instructions. Respondent represents<br />

he did not file the mortgage as this was not within the scope of his<br />

representation when contacted to handle the closing by American Title<br />

& Abstract. Respondent admits he assisted American Title & Abstract<br />

and Navy Federal in engaging in the unauthorized practice of law and<br />

that he participated in a real estate closing in clear violation of this<br />

Court’s precedent.<br />

LAW<br />

Respondent admits that, by his misconduct, he has violated<br />

the following provisions of the Rules of Professional Conduct, Rule<br />

407, <strong>SC</strong>ACR: Rule 1.1 (lawyer shall provide competent<br />

representation); Rule 1.2 (when lawyer knows client expects assistance<br />

not permitted by Rules of Professional Conduct, lawyer shall consult<br />

with client regarding relevant limitations on lawyer’s conduct); Rule<br />

5.5(b) (lawyer shall not assist a person who is not a member of the bar<br />

in the unauthorized practice of law); Rule 8.4(a) (lawyer shall not<br />

violate Rules of Professional Conduct); Rule 8.4(d) (lawyer shall not<br />

engage in conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit, or<br />

misrepresentation); and Rule 8.4(e) (lawyer shall not engage in conduct<br />

25

that is prejudicial to administration of justice). 1 In addition, respondent<br />

admits his misconduct constitutes grounds for discipline under Rule 7,<br />

RLDE, of Rule 413, <strong>SC</strong>ACR, specifically Rule 7(a)(1) (lawyer shall<br />

not violate Rules of Professional Conduct or any other rules of this<br />

jurisdiction regarding professional conduct of lawyers) and Rule<br />

7(a)(5) (lawyer shall not engage in conduct tending to pollute the<br />

administration of justice or to bring the courts or the legal profession<br />

into disrepute or conduct demonstrating an unfitness to practice law).<br />

CONCLUSION<br />

We accept the Agreement for Discipline by Consent and<br />

definitely suspend respondent from the practice of law for a sixty (60)<br />

day period. 2 Within fifteen days of the date of this opinion, respondent<br />

shall file an affidavit with the Clerk of Court showing that he has<br />

complied with Rule 30, RLDE, Rule 413, <strong>SC</strong>ACR.<br />

DEFINITE SUSPENSION.<br />

TOAL, C.J., WALLER, BURNETT and PLEICONES,<br />

JJ., concur. MOORE, J., not participating.<br />

1<br />

Respondent’s misconduct occurred before the effective<br />

date of the Amendments to the Rules of Professional Conduct. See<br />

Court Order dated June 20, 2005. The Rules cited in this opinion are<br />

those which were in effect at the time of respondent’s misconduct.<br />

2<br />

In the event the Court suspended respondent, the parties<br />

agreed to the appointment of an attorney to protect respondent’s<br />

clients’ interests. By separate order, the Court will appoint an attorney<br />

to protect respondent’s clients’ interests.<br />

26

THE STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA <br />

In The Court of Appeals <br />

John E. Cooke and Barbara <br />

Cooke,<br />

Respondents, <br />

v.<br />

Palmetto Health Alliance d/b/a<br />

Palmetto Richland Memorial<br />

Hospital, and Latisha C. Corley,<br />

Appellants.<br />

__________<br />

Appeal From Richland County <br />

Alison Renee Lee, Circuit Court Judge <br />

__________<br />

Opinion No. 4054<br />

Heard October 11, 2005 – Filed December 12, 2005<br />

__________<br />

AFFIRMED<br />

__________<br />

Charles E. Carpenter, Jr., George C. Beighley, S.<br />

Elizabeth Brosnan and Drew Hamilton Butler, all of<br />

Columbia, for Appellants.<br />

John S. Nichols and Robert B. Ransom, both of<br />

Columbia, for Respondents.<br />

27

HEARN, C.J.: This is an appeal from the order of the circuit<br />

court, finding John E. Cooke was not a statutory employee of Palmetto<br />

Health Alliance (the Hospital) when he was injured. Because of this ruling,<br />

the circuit court found Cooke’s negligence action and his wife’s loss of<br />

consortium action were not barred by the exclusive remedy provision of the<br />

Workers’ Compensation Act. We affirm.<br />

FACTS<br />

Cooke was employed as a pilot for Petroleum Helicopter, Inc., which<br />

contracted with the Hospital to transport critically injured patients to the<br />

emergency room. On December 13, 1999, Cooke tripped and fell over a<br />

metal rod that Latisha Corley, an employee of the Hospital, allegedly used to<br />

prop open a door at the Hospital. Because Cooke’s injury occurred while in<br />

the course of his employment with Petroleum Helicopter, Cooke filed for and<br />

received workers’ compensation benefits.<br />

In addition to his workers’ compensation claim, Cooke and his wife,<br />

Barbara, filed a complaint against the Hospital, alleging negligence and loss<br />

of consortium. After the court ruled that the Hospital could not be sued for<br />

punitive damages because of its status as a charitable organization, the<br />

Cookes amended their complaint to add Latisha Corley individually, alleging<br />

her method of propping open the door amounted to gross negligence.<br />

In their answer, the Hospital and Corley (collectively Appellants)<br />

asserted, among other things, that Cooke was either the Hospital’s statutory<br />

employee or borrowed servant at the time of the accident, and therefore, the<br />

exclusive remedy provision of the Workers’ Compensation Act served as a<br />

complete bar to the Cookes’ tort action. 1 After filing their answer, Appellants<br />

notified the Cookes of their intent to seek summary judgment. However,<br />

before the summary judgment motion was heard, Appellants, with the<br />

consent of the Cookes, made a motion for a hearing on the merits to<br />

1 Section 42-1-540 of the South Carolina Code (1985) provides that workers’<br />

compensation is the exclusive remedy against an employer for an employee’s<br />

work related accident.<br />

28

determine whether “the exclusive jurisdiction and exclusive remedy” was<br />

with the workers’ compensation commission or with the circuit court.<br />

At the hearing, the circuit court judge characterized the action before<br />

her as a “motion hearing” on “jurisdictional issues.” The Appellants’<br />

attorney did not agree with the judge’s characterization and said: “Your<br />

honor, this [is] not a motion. It was originally a motion for summary<br />

judgment. We’re here today on the merits of whether . . . Mr. Cooke<br />

qualifies as a statutory employee of the hospital; and, therefore, barred under<br />

workmen’s (sic) compensation.” The attorney for the Cookes added: “We’re<br />

here today to decide the merits of that. It’s a question of law anyway, so it<br />

would be for your decision. But we decided to tee this issue up before we go<br />

further with the case, since this issue may decide the – will obviously decide<br />

the future course of the case.” After hearing those explanations, the circuit<br />

court judge stated: “Well, that’s why it seems to come up as a motion to<br />

dismiss the case . . . I didn’t consider it to be a hearing on the merits where<br />

there would be testimony from an individual who would provide information<br />

about who his employer was and the contract, and all that information.”<br />

The hearing then proceeded, and although there were no live witnesses,<br />

both parties submitted deposition testimony in support of their respective<br />

positions. The Appellants argued that Cooke was a statutory employee<br />

because helicopter transport allows paramedics to reach critically injured<br />

patients more quickly than other forms of transportation, and therefore,<br />

helicopter service is essential to the Hospital’s business of saving lives. The<br />

Appellants further argued that Cooke was a borrowed servant of the Hospital<br />

because there was a contract for hire, the work Cooke performed benefited<br />

the Hospital, and the Hospital had control over Cooke. To illustrate that<br />

control, the Appellants’ attorney pointed out that Cooke had a uniform and<br />

identification tag issued by the Hospital, and the Hospital told Cooke where<br />

to pick up and deliver patients.<br />

The Cookes’ attorney argued Cooke was not a statutory employee<br />

because the Hospital was not in the business of transporting patients, the<br />

helicopter service was only a miniscule part of the overall business of the<br />

Hospital, and the Hospital and Petroleum Helicopter entered a contract in<br />

29

which they agreed that pilots were not employees of the Hospital. In regards<br />

to the Hospital’s borrowed servant argument, the Cookes’ attorney pointed<br />

out that the Hospital does not decide “if or when the helicopters ever fly,” nor<br />

does the Hospital have any say in who Petroleum Helicopters hires as pilots.<br />

After hearing arguments, the circuit court judge issued a written order,<br />

finding Cooke was not a statutory employee or borrowed servant of the<br />

Hospital. In her order, the judge characterized the action as “a motion to<br />

dismiss for lack of subject matter jurisdiction,” and the last sentence of her<br />

order denied “Defendant’s Motion to Dismiss.” This appeal followed.<br />

STANDARD OF REVIEW<br />

“The determination of whether a worker is a statutory employee is<br />

jurisdictional and therefore the question on appeal is one of law.” Harrell v.<br />

Pineland Plantation, Ltd., 337 S.C. 313, 320, 523 S.E.2d 766, 769 (1999)<br />

(citing Glass v. Dow Chemical Co., 325 S.C. 198, 482 S.E.2d 49 (1997)).<br />

Thus, the appellate court reviews the entire record and decides the<br />

jurisdictional facts in accord with the preponderance of the evidence. Id.<br />

LAW/ANALYSIS<br />

The Appellants argue the circuit court erred by failing to find Cooke<br />

was either a statutory employee or borrowed servant of the Hospital. The<br />

Cookes argue, initially, that the order of the circuit court is not immediately<br />

appealable. Thus, before delving into the merits of the Appellants’<br />

arguments, we first address the threshold issue of appealability.<br />

I. Appealability<br />

An order denying a motion to dismiss for lack of subject matter<br />

jurisdiction is not immediately appealable. Deskins v. Boltin, 319 S.C. 356,<br />

461 S.E.2d 395 (1995); Woodard v. Westvaco Corp., 319 S.C. 240, 460<br />

S.E.2d 392 (1995), overruled on other grounds by Sabb v. S.C. State Univ.,<br />

350 S.C. 416, 567 S.E.2d 231 (2002). However, the issue before the circuit<br />

30

court was not brought via a motion to dismiss; rather, both parties consented<br />

to have a non-jury hearing on the merits of the Hospital’s exclusivity defense.<br />

Furthermore, pursuant to Sabb v. South Carolina State University, the<br />

exclusivity provision of the Workers’ Compensation Act does not involve<br />

subject matter jurisdiction. 350 S.C. at 423, 567 S.E.2d at 234.<br />

Here, the circuit court held a hearing to determine the merits of the<br />

Hospital’s exclusivity defense. The circuit court rejected this defense, but the<br />

merits of the Cookes’ action has yet to be determined. Thus, the circuit<br />

court’s order is interlocutory.<br />

For an interlocutory order to be appealable, the order must “involve the<br />

merits.” S.C. Code Ann. § 14-3-330 (1985). To involve the merits, an order<br />

‘“must finally determine some substantial matter forming the whole or a part<br />

of some cause of action or defense . . . .’” Mid-State Distributors, Inc. v.<br />

Century Importers, Inc., 310 S.C. 330, 334, 426 S.E.2d 777, 780 (1993)<br />

(quoting Jefferson v. Gene’s Used Cars, Inc., 295 S.C. 317, 318, 368 S.E.2d<br />

456, 456 (1988)). Here, the circuit court weighed the evidence and<br />

concluded that the exclusivity provision did not apply because Cooke was<br />

neither a statutory employee nor a borrowed servant of the Hospital. In so<br />

holding, the circuit court “finally determined a substantial matter forming a<br />

part of the Hospital’s defense,” and thus, the order is appealable.<br />

II. Statutory Employee<br />

On the merits, the Appellants first argue the trial court erred in failing<br />

to find Cooke was a statutory employee of the Hospital. We disagree.<br />

To qualify as a statutory employee under the Workers’ Compensation<br />

Act, an individual must be engaged in an activity that “is a part of [the<br />

employer’s] trade, business or occupation.” S.C. Code Ann. § 42-1-400<br />

(1985). A particular activity is part of the putative employer’s “trade,<br />

business or occupation” if it “(1) is an important part of the [employer’s]<br />

business or trade; (2) is a necessary, essential, and integral part of the<br />

[employer’s] business; or (3) has previously been performed by the<br />

31

[employer’s] employees.” Olmstead v. Shakespeare, 354 S.C. 421, 424, 571<br />

S.E.2d 483, 485 (2003).<br />

We agree with the circuit court’s determination that none of these<br />

criteria is met. First, as is apparent from its articles of incorporation, the<br />

Hospital is in the business of providing health care, not transportation. 2<br />

While air transportation of patients helps facilitate the Hospital’s treatment of<br />

critically injured patients, that alone does not make transportation an<br />

important or essential part of the Hospital’s general business. See Abbott v.<br />

The Limited, 338 S.C. 161, 163-64, 526 S.E.2d 513, 514 (2000) (holding that<br />

a truck driver who delivered goods to a clothing store was not a statutory<br />

employee of the store because, even though it was important for the store to<br />

receive those goods, the store was in the business of retail sales not<br />

transportation). Second, helicopter service is not “necessary, essential, or<br />

integral” to the Hospital’s operation because less than one percent of the<br />

Hospital’s patients use the service and the Hospital’s emergency room<br />

services do not cease when the helicopter cannot fly. Finally, the Hospital<br />

did not have an FAA certificate and has never directly employed helicopter<br />

pilots. Thus, the preponderance of the evidence supports the circuit court’s<br />

determination that Cooke was not a statutory employee of the Hospital.<br />

II.<br />

Borrowed Servant<br />

The Hospital next argues the circuit court erred in failing to find Cooke<br />

was a borrowed servant. We disagree.<br />

Under the borrowed servant doctrine, when a general employer lends<br />

an employee to a special employer, that special employer is liable for<br />

workers’ compensation if: (1) there is a contract of hire between the<br />

employee and the special employer; (2) the work being done by the employee<br />

is essentially that of the special employer; and (3) the special employer has<br />

the right to control the details of the employee’s work. Eaddy v. A.J. Metler<br />

2 According to the Hospital’s articles of incorporation, its corporate purpose<br />

is to “provid[e] hospital facilities and health care services for inpatient<br />

medical care of the sick and injured.”<br />

32

Hauling & Rigging Co., 284 S.C. 270, 272, 325 S.E.2d 581, 582-83 (Ct. App.<br />

1985). While the circuit court found that the first two prongs of the borrowed<br />

servant doctrine were met, it found the Hospital did not control the details of<br />

Cooke’s work, and therefore, the third prong was not satisfied.<br />

When determining whether a special employer has the right to control<br />

the details of an employee’s work, courts consider the following four factors:<br />

“(1) direct evidence of the right to, or exercise of, control; (2) method of<br />

payment; (3) furnishings of equipment; and (4) right to fire.” Chavis v.<br />

Watkins, 256 S.C. 30, 33, 180 S.E.2d 648, 649 (1971). Although the hospital<br />

provided Cooke with a helicopter, Cooke was paid by Petroleum Helicopters,<br />

which was also charged with hiring (and presumably firing) its pilots.<br />

Furthermore, pursuant to the contract between the Hospital and Petroleum<br />

Helicopters, “the methods and details” of each flight were not left up to the<br />

Hospital. Thus, we agree with the circuit court’s determination that Cooke<br />

was not the Hospital’s borrowed servant.<br />

CONCLUSION<br />

Based on the foregoing, we find Cooke is neither a statutory employee<br />

nor a borrowed servant of the Hospital. Accordingly, the circuit court’s order<br />

resolving the merits of the Hospital’s exclusivity defense is<br />

AFFIRMED.<br />

STILWELL and KITTREDGE, JJ., concur.<br />

33

THE STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA <br />

In The Court of Appeals <br />

__________<br />

Richard Aiken,<br />

Respondent,<br />

v.<br />

World Finance Corporation of <br />

South Carolina and World <br />

Acceptance Corporation,<br />

Appellants. <br />

__________<br />

Appeal From Laurens County <br />

James W. Johnson, Jr., Circuit Court Judge <br />

__________<br />

Opinion No. 4055 <br />

Heard November 9, 2005 – Filed December 12, 2005 <br />

__________<br />

AFFIRMED<br />

__________<br />

Judson K. Chapin, III, of Greenville, for Appellants.<br />

Matthew Price Turner and Rhett D. Burney, both of<br />

Laurens, for Respondent.<br />

BEATTY, J.: World Finance Corporation of South Carolina and<br />

World Acceptance Corporation (“Appellants”) appeal the circuit court’s<br />

order denying their motion to compel arbitration. We affirm.<br />

34

FACTS<br />

Beginning in October 1997 through late 1999, Richard Aiken entered<br />

into a series of consumer loan transactions with Appellants. In conjunction<br />

with each of these loan agreements, Aiken signed an arbitration agreement, 1<br />

which provided that the parties agreed to settle all disputes and claims<br />

through arbitration.<br />

In late 2002, after Aiken had paid his loan in full, former employees of<br />

Appellants used Aiken’s personal financial information to illegally procure<br />

loans and embezzle the proceeds from those loans. 2 Upon discovering the<br />

misuse of his personal information, Aiken filed suit against Appellants<br />

seeking a jury trial for damages arising out of the following causes of action:<br />

intentional infliction of emotional distress; negligence; negligent<br />

hiring/supervision; and unfair trade practices. In response, Appellants denied<br />

the allegations and filed a motion to dismiss pursuant to Rule 12(b)(6),<br />

<strong>SC</strong>RCP, and a motion to compel arbitration.<br />

After a hearing, the circuit court denied Appellants’ motions to dismiss<br />

and to compel arbitration. In reaching this decision, the court found the<br />

creditor/debtor relationship between Appellants and Aiken ended once Aiken<br />

satisfied his loan in full. As a result, the court concluded the “effectiveness<br />

of the arbitration clause ceased when the relationship of the parties ceased.”<br />

The court also held the tort claims raised by Aiken were not subject to<br />

arbitration because the acts of Appellants’ employees were “completely<br />

independent of the loan agreement.” This appeal followed.<br />

1 Aiken signed several arbitration agreements. However, the only agreements<br />

pertinent to this appeal are those executed on February 3, 1999 and July 21,<br />

1999.<br />

2<br />

The former employees pleaded guilty for these offenses and were sentenced<br />

in the United States District Court for the District of South Carolina.<br />

35

STANDARD OF REVIEW<br />

“The question whether a claim is subject to arbitration is a matter of<br />

judicial determination, unless the parties have provided otherwise. Appeal<br />

from the denial of a motion to compel arbitration is subject to de novo<br />

review.” Chassereau v. Global-Sun Pools, Inc., 363 S.C. 628, 631, 611<br />

S.E.2d 305, 307 (Ct. App. 2005) (citations omitted).<br />

DI<strong>SC</strong>USSION<br />

Appellants argue the circuit court erred in denying their motion to<br />

compel arbitration. 3 Specifically, they contend that once the court<br />

determined that an arbitration agreement existed between the parties, the<br />

court’s “decisional function” was completed and any decisions regarding the<br />

validity of the agreement and the arbitrability of Aiken’s claims were to be<br />

decided by an arbitrator. Even if the circuit court was authorized to<br />

determine the effectiveness of the agreement, Appellants claim the broad<br />

terms of the arbitration agreement encompassed any disputes beyond the<br />

expiration of the underlying loan transactions between the parties.<br />

As a threshold matter, we find Appellants’ argument that the circuit<br />

court’s authority was strictly limited to determining whether the parties<br />

entered into an arbitration agreement is not properly before this court. First,<br />

Appellants did not raise this precise argument in their motion to compel<br />

arbitration or during the hearing before the circuit court. Secondly, the<br />

circuit court did not address this issue in its order, but instead, only ruled on<br />

the effectiveness of the arbitration agreement. Appellants did not file a<br />

motion pursuant to Rule 59 of the South Carolina Rules of Civil Procedure to<br />

challenge this omission. See Lucas v. Rawl Family Ltd. P’ship, 359 S.C.<br />

505, 511, 598 S.E.2d 712, 715 (2004) (recognizing that in order for an issue<br />

to be preserved for appellate review, with few exceptions, it must be raised to<br />

3<br />

Although Appellants raise four issues in their brief, we have consolidated<br />

these issues in the interest of brevity and clarity.<br />

36

and ruled upon by the trial court); Hawkins v. Mullins, 359 S.C. 497, 502,<br />

597 S.E.2d 897, 899 (Ct. App. 2004) (noting an issue is not preserved where<br />

the trial court does not explicitly rule on an argument and the appellant does<br />

not make a Rule 59(e) motion to alter or amend the judgment).<br />

In terms of the merits of Appellants’ motion to compel arbitration, we<br />

turn to recently established precedent. “Arbitration is a matter of contract,<br />

and the range of issues that can be arbitrated is restricted by the terms of the<br />

agreement.” Palmetto Homes, Inc. v. Bradley, 357 S.C. 485, 492, 593 S.E.2d<br />

480, 484 (Ct. App. 2004), cert. denied (July 8, 2005). Our supreme court has<br />

outlined the analytical framework for determining whether a particular claim<br />

is subject to arbitration. Zabinski v. Bright Acres Assocs., 346 S.C. 580, 597,<br />

553 S.E.2d 110, 118-19 (2001). In Zabinski, the court stated:<br />

To decide whether an arbitration agreement encompasses a<br />

dispute, a court must determine whether the factual allegations<br />

underlying the claim are within the scope of the broad arbitration<br />

clause, regardless of the label assigned to the claim. Hinson v.<br />

Jusco Co., 868 F.Supp. 145 (D.S.C. 1994); S.C. Pub. Serv. Auth.<br />

v. Great W. Coal, 312 S.C. 559, 437 S.E.2d 22 (1993). Any<br />

doubts concerning the scope of arbitrable issues should be<br />

resolved in favor of arbitration. Towles, supra. Furthermore,<br />

unless the court can say with positive assurance that the<br />

arbitration clause is not susceptible to an interpretation that<br />

covers the dispute, arbitration should be ordered. Great W. Coal,<br />

312 S.C. at 564, 437 S.E.2d at 25. A motion to compel<br />

arbitration made pursuant to an arbitration clause in a written<br />

contract should only be denied where the clause is not susceptible<br />

to any interpretation which would cover the asserted dispute.<br />

Tritech, supra.<br />

Id. at 597, 553 S.E.2d at 118-19. The court further articulated that “[a]<br />

broadly-worded arbitration clause applies to disputes that do not arise under<br />

the governing contract when a ‘significant relationship’ exists between the<br />

asserted claims and the contract in which the arbitration clause is contained.”<br />

Id. at 119, 553 S.E.2d at 598.<br />

37

With respect to tort claims, the supreme court noted the test from other<br />

jurisdictions stating, “the focus should be on the factual allegations contained<br />

in the petition rather than on the legal causes of actions asserted.” Zabinski,<br />

346 S.C. at 597 n.4, 553 S.E.2d at 119 n.4. The court elaborated:<br />

Id.<br />

The test is based on a determination of whether the particular tort<br />

claim is so interwoven with the contract that it could not stand<br />

alone. If the tort and contract claims are so interwoven, both are<br />

arbitrable. On the other hand, if the tort claim is completely<br />

independent of the contract and could be maintained without<br />

reference to the contract, the tort claim is not arbitrable.<br />

Shortly after the supreme court issued its decision in Zabinski, this<br />

court had the opportunity to apply the principles set forth and to interpret the<br />

“significant relationship” test. Vestry & Church Wardens of the Church of<br />

the Holy Cross v. Orkin Exterminating Co., 356 S.C. 202, 588 S.E.2d 136<br />

(Ct. App. 2003). Although this court utilized the Zabinski principles to<br />

analyze the question of whether separate arbitration agreements previously<br />

executed by the parties mandated arbitration for the claims in dispute, we<br />

believe the holding is, nevertheless, instructive. In Vestry, we concluded,<br />

“the mere fact that an arbitration clause might apply to matters beyond the<br />

express scope of the underlying contract does not alone imply that the clause<br />

should apply to every dispute between the parties.” Id. at 209, 588 S.E.2d at<br />

140.<br />

The arbitration agreement in the instant case provides in relevant part:<br />

ALL DISPUTES, CONTROVERSIES OR CLAIMS OF ANY<br />

KIND AND NATURE BETWEEN LENDER AND<br />

BORROWER ARISING OUT OF OR IN CONNECTION WITH<br />

THE LOAN AGREEMENT, OR ARISING OUT OF ANY<br />

TRANSACTION OR RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN LENDER<br />

AND BORROWER OR ARISING OUT OF ANY PRIOR OR<br />

38

FUTURE DEALINGS BETWEEN LENDER AND <br />

BORROWER, SHALL BE SUBMITTED TO ARBITRATION<br />

AND SETTLED BY ARBITRATION IN ACCORDANCE<br />

WITH THE UNITED STATES ARBITRATION ACT, THE<br />

EXPEDITED PROCEDURES OF THE COMMERCIAL<br />

ARBITRATION RULES OF THE AMERICAN<br />

ARBITRATION ASSOCIATION (THE “ARBITRATION<br />

RULES OF THE AAA”), AND THIS AGREEMENT.<br />

(Emphasis added). We would also note the arbitration agreement contained a<br />

provision that stated, “This Agreement applies even if the Loan Agreement is<br />

paid in full, charged-off by Lender, or discharged in Bankruptcy.”<br />

Given the broadly worded terms of the arbitration agreement, it is<br />

plausible that one could initially conclude that Aiken’s claims were subject to<br />

arbitration. However, as discussed above, the terms alone are not dispositive<br />

of this determination. Instead, we are required to focus on the factual<br />

allegations of the underlying causes of action to analyze whether a<br />

“significant relationship” existed between the claims and the loan contract.<br />

Moreover, because Aiken had satisfied his loan in full at the time his claims<br />

arose, we must also look at the parties’ intent to assess whether the arbitration<br />

agreement extended beyond the termination of the contract. See Towles v.<br />

United Healthcare Corp., 338 S.C. 29, 41, 524 S.E.2d 839, 846 (Ct. App.<br />

1999)(“When a party invokes an arbitration clause after the contractual<br />

relationship between the parties has ended, the parties’ intent governs<br />

whether the clause’s authority extends beyond the termination of the<br />

contract.”); see Zabinski, 346 S.C. at 596, 553 S.E.2d at 118 (“Arbitration is<br />

a matter of contract, and a party cannot be required to submit to arbitration<br />

any dispute which he has not agreed to submit.”).<br />

Applying the foregoing principles to the specific facts of this case, we<br />

agree with the circuit court’s conclusion that Aiken’s claims were not subject<br />

to arbitration. Initially, we reject Appellants’ contention that the claims arose<br />

out of the loan agreement simply because Appellants’ employees would not<br />

have had access to Aiken’s personal financial information but for the loan<br />

agreement. Although Appellants’ assertion is factually accurate, it disregards<br />

39

the analytical framework for determining whether claims are arbitrable.<br />

Aiken’s tort claims are independent of the loan agreement and require no<br />

reference to the contract. At the time Appellants’ employees misused<br />

Aiken’s personal financial information, Aiken had paid off his loan in full.<br />

Thus, a “significant relationship” does not exist between Aiken’s claims and<br />

the loan agreement. Moreover, it is inconceivable that Aiken intended to<br />

agree to maintain a contractual relationship with Appellants in perpetuity<br />

after he paid off his loan. Given Aiken had satisfied his contractual<br />

obligation, no further dealings with Appellants were necessary. Finally, we<br />

do not believe he could have foreseen the future tortious conduct of<br />

Appellants’ employees at the time he entered into the loan agreements.<br />

Additionally, we believe our holding is consistent with this court’s<br />

recent decision in Chassereau v. Global-Sun Pools, Inc., 363 S.C. 628, 611<br />

S.E.2d 305 (Ct. App. 2005). In Chassereau, a homeowner entered into a<br />

contract for the construction of a pool by Global-Sun Pools. The contract<br />

contained an arbitration provision that applied to “any disputes arising in any<br />

manner relating to this agreement.” Id. at 633, 611 S.E.2d at 307. After<br />

construction was completed, the homeowner began to experience problems<br />

with the pool. Because Global-Sun Pools failed to repair the pool, the<br />

homeowner stopped making payments on the pool. Id. at 630, 611 S.E.2d at<br />

306. A few months later, the homeowner filed a complaint against the pool<br />

company and one of its employees, alleging this employee and other<br />

employees made a series of harassing and intimidating telephone calls to her<br />

workplace. The homeowner claimed the pool company’s employees made<br />

defamatory statements about her to her co-workers and they disclosed<br />

information regarding her personal finances. Additionally, the homeowner<br />

asserted these same employees made numerous telephone calls to her home<br />

as well as to her relatives in an effort to intimidate and harass her. Id.<br />

In her complaint, the homeowner sought damages based on causes of<br />

action for defamation, violation of South Carolina Code of Laws section 16-<br />

17-430 which prohibits unlawful use of a telephone, and intentional infliction<br />

of emotional distress. Id. at 631, 611 S.E.2d at 306. The pool company and<br />

its employee filed a motion to compel arbitration, alleging the provisions of<br />

the construction contract mandated arbitration. The circuit court denied the<br />

40

motion, finding “[t]he complaint is based upon tortious conduct of the<br />

employees of [Global-Sun Pools] unrelated to the contract” and the<br />

“allegations of the complaint do not arise out of nor do they relate to the<br />

contract[.]” Id. at 631, 611 S.E.2d at 306-07.<br />

On appeal, this court affirmed the circuit court’s decision. In so<br />

holding, we found the homeowner’s claims did not arise out of the<br />

construction contract and could be proved independently of the contract. We<br />

further concluded the causes of action alleged in the complaint “constitute[d]<br />

tortious behavior that the parties . . . could not have reasonably foreseen and<br />

for which we seriously doubt they intended to provide a limited means of<br />

redress.” Id. at 634, 611 S.E.2d at 308.<br />

Similar to the homeowner’s tort claims in Chassereau, Aiken’s tort<br />

claims did not arise out of the loan agreement and could be proved<br />

independently of this agreement. Although we are cognizant of the policy<br />

favoring arbitration, we do not believe arbitration is warranted for Aiken’s<br />

claims. See Zabinski, 346 S.C. at 596, 553 S.E.2d at 118 (“The policy of the<br />

United States and South Carolina is to favor arbitration of disputes.”).<br />

Accordingly, the decision of the circuit court is<br />

AFFIRMED.<br />

HEARN, C.J., and HUFF, J., concur.<br />

41

THE STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA <br />

In The Court of Appeals <br />

Timothy Jackson,<br />

Appellant,<br />

v.<br />

City of Abbeville, Riley’s BP, <br />

and Angela McCurry, <br />

Defendants, <br />

of whom City of Abbeville is<br />

Respondent. <br />

__________<br />

Appeal From Abbeville County <br />

James W. Johnson, Jr., Circuit Court Judge <br />

__________<br />

Opinion No. 4056<br />

Submitted October 1, 2005 – Filed December 12, 2005<br />

___________<br />

AFFIRMED<br />

___________<br />

Fletcher N. Smith, Jr., of Greenville, for Appellant.<br />

James D. Jolly, Jr., of Anderson, for Respondent.<br />

42

KITTREDGE, J.: This is a civil action brought under the South<br />

Carolina Tort Claims Act for violation of the state constitution, malicious<br />

prosecution and false arrest. Timothy Jackson appeals from an order of the<br />

circuit court granting the City of Abbeville’s (City) motion for summary<br />

judgment and denying Jackson’s motion for summary judgment. At issue is<br />

whether a City police officer had probable cause to arrest Jackson at a<br />

convenience store in Abbeville on February 22, 1999. We hold the officer<br />

had probable cause to arrest Jackson and affirm.<br />

FACTS<br />

On February, 22, 1999, Jackson entered Riley’s BP, a convenience<br />

store located in Abbeville, South Carolina, and asked the attendant whether<br />

he could put up a flyer in the store for a party he was having at his club. The<br />

attendant said he could not. A video surveillance tape from the store<br />

indicates that Jackson became enraged, accusing the attendant of racism. She<br />

asked Jackson to leave the premises. Jackson refused to leave, and the<br />

attendant called the police.<br />

When the officer arrived, Jackson repeatedly interrupted the officer<br />

while he was attempting to find out what happened from the attendant. The<br />

officer told Jackson to be quiet several times, but Jackson refused to do so.<br />

The attendant again told Jackson to leave the premises. When Jackson<br />

refused to leave, the officer put Jackson on trespass notice. Jackson<br />

continued to interrupt. The officer told Jackson to be quiet or he would be<br />

arrested. Jackson ignored the officer’s repeated demands, and the officer<br />

attempted to place him under arrest. A scuffle ensued as Jackson resisted and<br />

backup was summoned to effect the arrest.<br />

After being arrested and taken to jail, Jackson was charged with<br />

disorderly conduct and resisting arrest. Jackson was not charged with<br />

trespass after notice. The municipal judge dismissed the charges. 1<br />

1<br />

The record is not clear as to the basis of the dismissal of the charges in<br />

municipal court. According to the City’s brief, the disorderly conduct charge<br />

was dismissed because Jackson’s “actions did not rise to the level of ‘fighting<br />

words’ as required by Houston v. Hill, 482 U.S. 451 (1987) and State v.<br />

43

Jackson sued the City of Abbeville 2 under the South Carolina Tort<br />

Claims Act 3 for: (1) violation of the South Carolina Constitution, (2)<br />

malicious prosecution, and (3) false arrest. Both sides moved for summary<br />

judgment. After a hearing, the circuit court granted the City’s motion for<br />

summary judgment and denied Jackson’s motion. This appeal followed.<br />

STANDARD OF REVIEW<br />

Under Rule 56, <strong>SC</strong>RCP, a party is entitled to a judgment as a matter of<br />

law if the pleadings, depositions, answers to interrogatories, and admissions<br />

on file, together with the affidavits, if any, show that there is no genuine issue<br />

as to any material fact. “Summary judgment is appropriate when it is clear<br />

there is no genuine issue of material fact and the conclusions and inferences<br />

to be drawn from the facts are undisputed.” McClanahan v. Richland County<br />

Council, 350 S.C. 433, 437, 567 S.E.2d 240, 242 (2002).<br />

LAW/ANALYSIS<br />

An essential element in each of Jackson’s causes of action is the lack of<br />

probable cause to arrest him. 4 The dispositive issue before us is whether the<br />

Perkins, 306 S.C. 353, 412 S.E.2d 385 (1991).” The resisting arrest charge<br />

was also dismissed, apparently on the belief that the dismissal of the<br />

underlying charge precluded a stand-alone prosecution for resisting arrest.<br />

The present uncertainty as to the reasons why the charges against Jackson<br />

were dismissed does not impact this appeal, because the City—for purposes<br />

of its summary judgment motion—assumed a lack of probable cause<br />

concerning the charged offenses.<br />

2<br />

Riley’s BP and Angela McCurry have been dismissed from the case.<br />

3<br />

S.C. Code Ann. §§ 15-78-10 to -200 (2005).<br />

4<br />

Jackson predicated his constitutional violation claim on the lack of<br />

probable cause. His false imprisonment claim also requires lack of probable<br />

cause. See Gist v. Berkeley County Sheriff’s Dep’t, 336 S.C. 611, 615, 521<br />

S.E.2d 163, 165 (Ct. App. 1999) (“An action for false imprisonment may not<br />

be maintained where the plaintiff was arrested by lawful authority . . . [and]<br />

[t]he fundamental issue in determining the lawfulness of an arrest is whether<br />

44

“probable cause to arrest” determination is confined to the actual charges or<br />

whether consideration of an uncharged offense is appropriate. The City<br />

concedes for purposes of this appeal the absence of probable cause to arrest<br />

Jackson for disorderly conduct and the related offense of resisting arrest. The<br />

City contends, however, that it may—to defeat Jackson’s claims—properly<br />

rely on the presence of probable cause in connection with an uncharged<br />

offense. We hold that the determination of “probable cause to arrest” for the<br />

purpose of Jackson’s tort claims may properly include consideration of an<br />

uncharged offense.<br />

The uncharged offense for which the City asserts probable cause<br />

existed is trespass after notice. Trespass after notice is a misdemeanor<br />

criminal offense prohibited by section 16-11-620 of the South Carolina Code<br />

(Supp. 1998). “Statutory criminal trespass involves . . . the failure to leave a<br />

dwelling house, place of business or premises of another after having been<br />

requested to leave.” State v. Cross, 323 S.C. 41, 43, 448 S.E.2d 569, 570 (Ct.<br />

App. 1994). The City has an ordinance patterned after section 16-11-620. A<br />

police officer may, without a warrant, arrest a person who commits trespass<br />

after notice—or any misdemeanor—in the officer’s presence. See S.C. Code<br />

Ann. § 17-13-30 (1985); State v. Mims, 263 S.C. 45, 208 S.E.2d 288 (1974).<br />

Jackson has the burden of demonstrating lack of probable cause.<br />

Parrott v. Plowden Motor Co., 246 S.C. 318, 322, 143 S.E.2d 607, 609<br />

(1965). Probable cause turns not on the individual’s actual guilt or<br />

innocence, but on whether facts within the officer’s knowledge would lead a<br />

reasonable person to believe the individual arrested was guilty of a crime.<br />

State v. George, 323 S.C. 496, 509, <strong>47</strong>6 S.E.2d 903, 911 (1996); Deaton v.<br />

Leath, 279 S.C. 82, 84, 302 S.E.2d 335, 336 (1983). “‘Probable cause’ is<br />

defined as a good faith belief that a person is guilty of a crime when this<br />

belief rests on such grounds as would induce an ordinarily prudent and<br />

there was ‘probable cause’ to make the arrest.”). Finally, a malicious<br />

prosecution action fails if the plaintiff cannot show malice and lack of<br />

probable cause. Parrott v. Plowden Motor Co., 246 S.C. 318, 322, 143<br />

S.E.2d 607, 609 (1965); see also Gaar v. North Myrtle Beach Realty Co.,<br />

Inc., 287 S.C. 525, 528, 339 S.E.2d 887, 889 (Ct. App. 1986) (listing the<br />

elements of malicious prosecution, including “want of probable cause”).<br />

45

cautious man, under the circumstances, to believe likewise.” Jones v. City of<br />

Columbia, 301 S.C. 62, 65, 389 S.E.2d 662, 663 (1990). Probable cause is<br />

determined as of the time of the arrest, based on facts and circumstances—<br />

objectively measured—known to the arresting officer. The determination of<br />

probable cause is not an academic exercise in hindsight. George, 323 S.C. at<br />

509, <strong>47</strong>6 S.E.2d at 911; Eaves v. Broad River Elec. Co-op., Inc., 277 S.C.<br />

<strong>47</strong>5, <strong>47</strong>8, 289 S.E.2d 414, 415-16 (1982); State v. Goodwin, 351 S.C. 105,<br />

110, 567 S.E.2d 912, 914 (Ct. App. 2002); State v. Robinson, 335 S.C. 620,<br />

634, 518 S.E.2d 269, 276-77 (Ct. App. 1999); 5 Am. Jur. 2d Arrest § 40; 6A<br />

C.J.S. Arrest § 25 (2004). “[E]venhanded law enforcement is best achieved<br />

by the application of objective standards of conduct, rather than standards<br />

that depend upon the subjective state of mind of the officer.” Horton v.<br />

California, 496 U.S. 128, 138 (1990).<br />

Concerning the narrow issue before us, we find no South Carolina case<br />

directly on point, but we find the reasoning of three cases persuasive.<br />

The first case is State v. Tyndall, 336 S.C. 8, 518 S.E.2d 278 (Ct. App.<br />