May Issue - Stage Directions Magazine

May Issue - Stage Directions Magazine

May Issue - Stage Directions Magazine

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

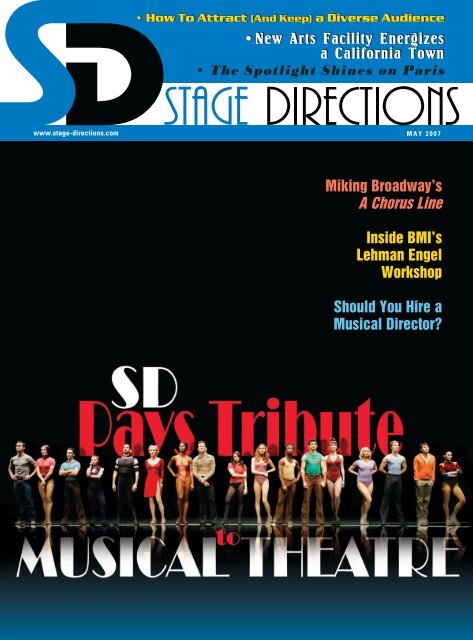

• How To Attract (And Keep) a Diverse Audience<br />

•New Arts Facility Energizes<br />

a California Town<br />

www.stage-directions.com<br />

M A Y 2 0 0 7<br />

Miking Broadway’s<br />

A Chorus Line<br />

Inside BMI’s<br />

Lehman Engel<br />

Workshop<br />

Should You Hire a<br />

Musical Director?

Table Of Contents<br />

M a y 2 0 0 7<br />

Feature<br />

24 Theatre Space<br />

A West Coast community gets a theatre that’s no joke.<br />

By Charles Conte<br />

26 Theatre For Everyone<br />

Building diversity is smart, but it takes staying power.<br />

By John Crawford<br />

Spotlight:Paris<br />

20 Molière’s Legacy<br />

Inside the French Academy at the Comédie Française.<br />

By Karyn Bauer-Prevost<br />

22 Parfait of Excellence<br />

For more than 30 years, the Training Center for Professional<br />

Theatre Technicians has been training France’s finest techs.<br />

By Karyn Bauer-Prevost<br />

Special Section:Musical Theatre<br />

30 The Eternal Dilemma<br />

Computers versus live musicians — it’s a question that’s<br />

only going to get hotter as computers keep sounding better.<br />

By Kevin M. Mitchell<br />

33 Covering Your Tracks<br />

What you need to know about using backing tracks.<br />

By Jerry Cobb<br />

34 Music & Lyrics<br />

The BMI Workshop is nirvana to musical theatre makers; we<br />

examine why. By Brooke Pierce<br />

36 A Perfect Harmony<br />

For everything there is a season, but is your show the time<br />

for a musical director? By Lisa Mulcahy<br />

22<br />

COURTESY OF CFPTS

Departments<br />

7 Editor’s Note<br />

There’s no such thing as summer vacation.<br />

By Iris Dorbian<br />

9 Letters<br />

A TD weighs in on tardy designers.<br />

10 In the Greenroom<br />

Yale rep finds a new #1; the Tacoma Actors Guild<br />

and the Jean Cocteau rep fold; a Disney VP retires<br />

and more.<br />

14 Tools of the Trade<br />

The onset of summer brings gear for the outdoor<br />

season.<br />

16 Light On the Subject<br />

Building a profile for the profile spot. By Andy Ciddor<br />

44 Answer Box<br />

Getting the fog just right. By Jason Reberski<br />

Columns<br />

15 Vital Stats<br />

Lighting designer Ryan Koharchik flexes his craft at a<br />

number of venues. Just don’t ask him to fill out<br />

paperwork. By Kevin M. Mitchell<br />

18 On Broadway<br />

A Chorus Line, that one singular sensation, is back. By<br />

Bryan Reesman<br />

39 TD Talk<br />

The bid system might be designed to save money, but<br />

inexpensive and cheap are different. By Dave McGinnis<br />

40 Show Biz<br />

Is there really any such thing as competition?<br />

By Jacob Coakley<br />

41 Off the Shelf<br />

New books and CDs imply that musicals still have life<br />

yet to live. By Stephen Peithman<br />

42 The Play’s the Thing<br />

Diversity in tone grabs the ear. By Stephen Peithman<br />

26<br />

34<br />

ON OUR COVER: The cast of A Chorus Line<br />

PHOTOGRAPHY BY: Paul Kolnik<br />

DAVID GRAPES COURTESY OF AMERICAN STAGE

Editor’s Note<br />

What Hiatus?<br />

kimberly butler<br />

One of the biggest fallacies<br />

that theatre outsiders have<br />

is that the season rumbles<br />

to an end in <strong>May</strong>, remaining dormant<br />

for the summer until the fall<br />

when everything revs up again.<br />

From the inside, it’s a much different<br />

story. Sure, for most venues<br />

throughout the country, the regular<br />

season does end this month, but that doesn’t mean<br />

all is quiet on the theatrical front. Some theatres rent out<br />

their space to local companies and schools for various<br />

functions (i.e. trade shows, conferences, parties, etc.);<br />

others take stock of their inventory and make plans to<br />

upgrade gear or renovate dilapidated space. Still others<br />

are putting the final touches to the next season’s programming,<br />

conferring with board members and artistic<br />

staff about casting and logistics. Then there are those<br />

who are launching their new seasons in mid to late summer<br />

with new productions. (Broadway has begun doing<br />

this the last few years with certain productions.) When it<br />

comes to theatre, all is relative, subjective and arbitrary<br />

— pretty much the way human opinion is on any topic!<br />

But then again, problems may arise when theatres<br />

find themselves multitasking during the summer. For<br />

instance, I remember one time when I was interning at a<br />

regional theatre in New Jersey, the artistic director decided<br />

to not only mount a small cast revue in the mainstage<br />

during the summer months — but to commence a long<br />

overdue lobby renovation. Suffice it to say the theatre<br />

looked like a mess (and it didn’t smell too good, either)<br />

when patrons trooped in to buy tickets. If the gung-ho<br />

artistic director had simply planned ahead, listened to<br />

advisers and realistically weighed the consequences of<br />

doing this type of renovation while still keeping a show<br />

running in the mainstage, he might have realized the<br />

disaster that ensued. Clearly, the solution would have<br />

been to postpone the revue to the following season and<br />

begin the renovation when the theatre was dark; or the<br />

exact opposite.<br />

So the moral of this story is…be patient, plan ahead and<br />

don’t jump the gun until you’ve thought everything out.<br />

Iris Dorbian<br />

Editor<br />

<strong>Stage</strong> <strong>Directions</strong><br />

www.stage-directions.com • <strong>May</strong> 2007

www.stage-directions.com<br />

Publisher Terry Lowe<br />

tlowe@stage-directions.com<br />

Editor Iris Dorbian<br />

Editorial Director Bill Evans<br />

idorbian@stage-directions.com<br />

bevans@fohonline.com<br />

Audio Editor Jason Pritchard<br />

jpritchard@stage-directions.com<br />

Lighting & Staging Editor Richard Cadena<br />

rcadena@plsn.com<br />

Managing Editor Jacob Coakley<br />

jcoakley@stage-directions.com<br />

Associate Editor David McGinnis<br />

dmcginnis@stage-directions.com<br />

Contributing Writers Karyn Bauer-Prevost, Andy Ciddor,<br />

Jerry Cobb, Charles Conte, John<br />

Crawford, Kevin M. Mitchell,<br />

Lisa Mulcahy, Stephen Peithman,<br />

Brooke Pierce and Bryan Reesman<br />

Consulting Editor Stephen Peithman<br />

ART<br />

Art Director Garret Petrov<br />

Graphic Designers Crystal Franklin, David Alan<br />

Production<br />

Production Manager Linda Evans<br />

levans@stage-directions.com<br />

WEB<br />

Web Designer Josh Harris<br />

ADVERTISING<br />

Advertising Director Greg Gallardo<br />

gregg@stage-directions.com<br />

Account Manager James Leasing<br />

jleasing@stage-directions.com<br />

Warren Flood<br />

wflood@stage-directions.com<br />

Audio Advertising Manager Peggy Blaze<br />

pblaze@stage-directions.com<br />

OPERATIONS<br />

General Manager William Vanyo<br />

wvanyo@stage-directions.com<br />

Office Manager Mindy LeFort<br />

CIRCULATION<br />

BUSINESS OFFICE<br />

mlefort@stage-directions.com<br />

Stark Services<br />

P.O. Box 16147<br />

North Hollywood, CA 91615<br />

6000 South Eastern Ave.<br />

Suite 14-J<br />

Las Vegas, NV 89119<br />

TEL. 702.932.5585<br />

FAX 702.932.5584<br />

<strong>Stage</strong> <strong>Directions</strong> (ISSN: 1047-1901) Volume 20, Number 05 Published monthly by Timeless Communications<br />

Corp. 6000 South Eastern Ave., Suite 14J, Las Vegas, NV 89119. It is distributed free<br />

to qualified individuals in the lighting and staging industries in the United States and Canada.<br />

Periodical Postage paid at Las Vegas, NV office and additional offices. Postmaster please send<br />

address changes to: <strong>Stage</strong> <strong>Directions</strong>, PO Box 16147 North Hollywood, CA 91615. Editorial submissions<br />

are encouraged but must include a self-addressed stamped envelope to be returned.<br />

<strong>Stage</strong> <strong>Directions</strong> is a Registered Trademark. All Rights Reserved. Duplication, transmission by any<br />

method of this publication is strictly prohibited without permission of <strong>Stage</strong> <strong>Directions</strong>.<br />

Advisory Board<br />

Joshua Alemany<br />

Rosco<br />

Julie Angelo<br />

American Association of<br />

Community Theatre<br />

Robert Barber<br />

BMI Supply<br />

Ken Billington<br />

Lighting Designer<br />

Roger claman<br />

Rose Brand<br />

Patrick Finelli, PhD<br />

University of<br />

South Florida<br />

Gene Flaharty<br />

Mehron Inc.<br />

Cathy Hutchison<br />

Acoustic Dimensions<br />

Keith Kankovsky<br />

Apollo Design<br />

Becky Kaufman<br />

Period Corsets<br />

Todd Koeppl<br />

Chicago Spotlight Inc.<br />

Kimberly Messer<br />

Lillenas Drama Resources<br />

John Meyer<br />

Meyer Sound<br />

John Muszynski<br />

Theater Director<br />

Maine South High School<br />

Scott Parker<br />

Pace University/USITT-NY<br />

Ron Ranson<br />

Theatre Arts<br />

Video Library<br />

David Rosenberg<br />

I. Weiss & Sons Inc.<br />

Karen Rugerio<br />

Dr. Phillips High School<br />

Ann Sachs<br />

Sachs Morgan Studio<br />

Bill Sapsis<br />

Sapsis Rigging<br />

Richard Silvestro<br />

Franklin Pierce College<br />

OTHER TIMELESS COMMUNICATIONS PUBLICATIONS

Letters<br />

SALUTES NEW YORK CITY<br />

• A TALE OF TWO SCENE SHOPS<br />

• THEATRE TOURS TAKE YOU BEHIND THE SCENES<br />

A P R I L 2 0 0 7<br />

www.stage-directions.com<br />

Utah Plaudits for<br />

New Mexico<br />

Just thought<br />

I’d send along a<br />

thanks for the range<br />

of articles you put<br />

together for the April<br />

2007 issue of <strong>Stage</strong><br />

<strong>Directions</strong>. Having<br />

gone to the University<br />

of New Mexico way back in the dark ages (the<br />

new Rodey Theatre hadn’t been built yet), it was interesting<br />

to hear what’s happening on campus and in the<br />

city of Albuquerque. It was also exciting to hear about<br />

Fusion Theatre Company. I checked out their Web site,<br />

and it looks like they are doing some interesting work.<br />

The Special Section focus on New York City was also an<br />

enjoyable read.<br />

Bill Byrnes<br />

Dean, College of Performing & Visual Arts<br />

Southern Utah University<br />

A TD Weighs In<br />

Regarding the TD Talk article “On Your Hands” (SD<br />

April 2007) where the TD is waiting for long overdue scenic<br />

plans or has only napkin scribbles, I have worn both<br />

hats as scenic designer and TD. If a director has difficulty<br />

reading ground plans, please let that be known to the set<br />

designer early on so alternatives like 3D CAD or a model<br />

can be built. If you are responsible for lighting a subtle<br />

drama, let someone know your past expertise is really as<br />

the lighting designer for a rock band. As a designer, let<br />

the director know up front if you expect to run late.<br />

I recall an opening night that came before I saw parts<br />

of one design; instead, we built what we had plans for. It<br />

is not fair for the designer to eat into the build time.<br />

The group you are working with does not want to hear<br />

about the other two groups you are also trying to keep<br />

happy. Don’t burn your bridges on purpose or by blaming<br />

others; just consider, “I might possibly be causing this<br />

difficulty so I better help fix it.”<br />

Rich Desilets<br />

Santa Rosa, CA<br />

Miking & Mixing<br />

the TRIPLE THREATS<br />

of COMPANY<br />

GELS<br />

Versus<br />

DICHROICS<br />

Albuquerque<br />

Gets its Moment<br />

in the Sun<br />

300.0704.CVR.indd 1 3/12/07 6:08:30 PM<br />

Correction<br />

On page 24 in April’s Vital Stats, the production photo<br />

of Romeo and Juliet was misidentified as being from<br />

Mockingbird Theatre. The production was produced at<br />

Tennessee Repertory Theatre on the Polk Theatre <strong>Stage</strong>.<br />

The production was directed by David Grapes who was<br />

then the producing artistic director.

By Iris Dorbian<br />

In The Greenroom<br />

theatre buzz<br />

Theatre Critics Honor Playwright with Award<br />

The American Theatre Critics Association recently named<br />

Ken LaZebnik winner of the 2006 M. Elizabeth Osborn New<br />

Play Award for an emerging playwright. LaZebnik picked up<br />

his award March 31 at the Humana Festival of New American<br />

Plays in Louisville, Ky. His play Vestibular Sense was also one of<br />

six finalists in the 2006 Harold and Mimi Steinberg/American<br />

Theatre Critics New Play Awards.<br />

“I’m deeply appreciative to the ATCA for recognizing<br />

that a playwright may emerge at any age,” says LaZebnik.<br />

“The Osborn Award inspires me to continue writing for the<br />

theatre, which remains vital and essential for the heartbeat<br />

of American culture.”<br />

The award, chosen by ATCA’s 12-person New Plays<br />

Committee, is designed to recognize the work of an author<br />

whose plays have not yet received a major production,<br />

such as off-Broadway or Broadway, nor received other<br />

major national awards.<br />

The Osborn Award was established in 1993 to honor the<br />

memory of Theatre Communications Group and American<br />

Theatre play editor M. Elizabeth Osborn. It carries a $1,000 cash<br />

prize and receives recognition in The Best Plays Theater Yearbook,<br />

the annual chronicle of United States theatre founded by Burns<br />

Mantle in 1920 and currently edited by Jeffrey Eric Jenkins.<br />

Brian Skellenger and Karen Landry in Mixed Blood Theatre’s world premiere,<br />

Vestibular Sense by Ken LaZebnik<br />

Ann Marsden<br />

Yale Taps New Press Chief<br />

Yale Repertory Theatre and Yale School of Drama<br />

recently named Susan R. Hood as its press director; she<br />

assumed the post March 5.<br />

Hood has more than 20 years of experience in public<br />

relations covering theatre, dance, music and the visual<br />

arts. She has promoted and marketed choreographer<br />

Eliot Feld and the tours of Felds Ballet/NY, as well as the<br />

New Ballet School (now Ballet Tech). Also, as a member<br />

of Ellen Jacobs & Associates, she served the press needs<br />

of Martha Graham, Merce Cunningham, Bill T. Jones,<br />

Pilobolus and other renowned dance companies. She<br />

has also represented Mabou Mines, one of America’s<br />

foremost avant-garde theatre companies.<br />

Prior to her stint with Ellen Jacobs & Associates,<br />

Hood was the senior press representative for Brooklyn<br />

Academy of Music (BAM). Her work at BAM included<br />

publicizing commissions and premieres of work by<br />

Philip Glass, Robert Wilson, Laurie Anderson, Meredith<br />

Monk, Twyla Tharp and Mark Morris. Most recently,<br />

she has served for nine years as the media relations<br />

manager for the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art<br />

in Hartford, Conn.<br />

Lack of Money Dooms Tacoma Theatre<br />

According to a Seattle Times article dated March 8, 2007 by<br />

Misha Berson, the Tacoma Actors Guild, which was Tacoma’s<br />

only professional resident theatre company, shut down<br />

operations in late February because it didn’t have the funds<br />

to continue. This follows the recent closing of Seattle’s Empty<br />

Space Theatre, which also shuttered due to a cash shortfall.<br />

James V. Handmacher, a local attorney who is president of<br />

the theatre’s board of directions, stated, “We canceled the last<br />

show of our season, Romeo and Juliet, and have no intention<br />

of going on with a season for next year. Our entire staff has<br />

been laid off.”<br />

Although a major fundraising campaign liquidated much<br />

of TAG’s debt, it still owes money to its landlord and the<br />

Broadway Center for the Performing Arts, as well as actors<br />

and staff. Yet there are no immediate plans for TAG, which<br />

was founded in 1978, to file for bankruptcy.<br />

“We really fell short on support from foundations,” explains<br />

Handmacher of the board’s decision to close down the theatre.<br />

“Many took the position of ‘wait and see,’ which doomed us<br />

to failure. What we needed was another $100,000 of working<br />

capital to get us through the year. If that had come, TAG would<br />

have survived.”<br />

10 <strong>May</strong> 2007 • www.stage-directions.com

industry news<br />

New Music Licensing Agency Opens<br />

After several decades of experience<br />

in management positions at Music<br />

Theatre International, the William Morris<br />

Agency and Rodgers and Hammerstein<br />

Theatricals, Steve Spiegel recently<br />

launched Theatrical Rights Worldwide, a<br />

new musical theatre licensing company.<br />

In its first few months of operation,<br />

the NYC-based agency has acquired a<br />

number of well-known titles, including<br />

All Shook Up, Forbidden Broadway, I Love<br />

You Because, Ring of Fire and Zanna Don’t.<br />

They also have an exclusive relationship<br />

with Nickelodeon to develop and license<br />

live stage adaptations of their properties,<br />

starting with Blue’s Clues.<br />

“We’ve learned from our customers<br />

what they need to produce the best<br />

possible shows for their audiences,<br />

and we have applied those lessons to<br />

making licensing a musical from TRW as<br />

easy and rewarding as possible,” explains<br />

Spiegel. For example, customers keep<br />

all materials — scripts and scores; they<br />

can be used, marked and personalized<br />

to their wishes. Also, all scripts and<br />

scores are available in large, clear print,<br />

prepared in Microsoft Word and Finale<br />

software, designed for ease-of-use both<br />

by directors and performers.<br />

Steve Spiegel<br />

To find out more, visit the Web site at<br />

www.theatricalrights.com.<br />

Courtesy of TRW<br />

Montreal Staging Co. Names New Bigwig<br />

Courtesy of Scene Ethique<br />

Ron Morissette<br />

Scene Ethique, a Montrealbased<br />

scenic design and<br />

fabrication company, recently<br />

appointed Ron Morissette to<br />

corporate development. There he<br />

will oversee standard staging and<br />

grandstand products that have<br />

evolved from Scene Ethique’s<br />

custom fabrication products.<br />

Martin Ouellet, president of<br />

Scene Ethique, says, “Ron will<br />

allow us to use the technology<br />

that we have developed with our<br />

custom designs for international<br />

tours and apply it to standard<br />

products that can be used in a<br />

wide range of live performance<br />

applications from staging, to<br />

turntables, to grandstands.”<br />

Morissette, who is a past<br />

president of the Canadian Institute<br />

of Theatre Technology (CITT ) and is<br />

currently vice-president external for<br />

CITT, has been involved in design,<br />

sales and consulting for more than<br />

25 years. Most recently, he served<br />

as vice-president of operations for<br />

the Montreal company Realisations,<br />

where he worked closely with<br />

its founder and president, Roger<br />

Parent (who helped bring Cirque du<br />

Soleil to international audiences),<br />

on projects in Las Vegas, Honolulu<br />

and Detroit.<br />

PRG Partners Up<br />

Production Resource Group,<br />

LLC (PRG), a top equipment rental<br />

and services company in the<br />

entertainment technology industry, is<br />

expanding with its latest acquisition:<br />

High Performance Images (HPI), a<br />

Chicago-based video operation.<br />

“HPI’s resources and expertise in<br />

high-end video staging solutions<br />

adds depth and breadth to our<br />

video division and gives us a greatly<br />

enhanced presence in the Chicago<br />

video market,” says Kevin Baxley, PRG’s<br />

co-president and chief operating<br />

officer. “It will greatly enhance our<br />

ability to offer our clients the complete<br />

package of PRG equipment and<br />

services — video, lighting, audio and<br />

scenic — as well as the start-to-finish<br />

production management that so many<br />

customers are looking for today.”<br />

HPI founder and president, Adam<br />

Benjamin, who has been named<br />

general manager of PRG Video in<br />

Chicago, is enthusiastic about this<br />

milestone change: “I am delighted<br />

to be able to offer PRG’s full range of<br />

products and services to my customers.<br />

I look forward to helping grow PRG’s<br />

video division into one of the leading<br />

professional video resources in the<br />

United States.”<br />

Known as a fully integrated<br />

equipment rental and services<br />

company, the expanded PRG has a<br />

global presence, with major operations<br />

in New York, Chicago, Detroit, Nashville,<br />

Toronto, Orlando, Las Vegas, Los<br />

Angeles, London and Tokyo.<br />

12 <strong>May</strong> 2007 • www.stage-directions.com

changing roles<br />

Walt Disney Entertainment<br />

DISNEY VP RETIRES<br />

Rich Taylor flanked by friends<br />

Rich Taylor, who headed Walt<br />

Disney Entertainment’s costuming,<br />

cosmetology and entertainment<br />

divisions for the past 10 years, retired<br />

in February to “pursue a variety<br />

of other professional endeavors,”<br />

according to the press release. Overall,<br />

Taylor, whose last position made him<br />

a vice president with Disney, had<br />

been with the company for 26 years.<br />

EAW Taps Rowe For Appointment<br />

EAW recently announced<br />

that veteran concert sound<br />

professional Martyn “Ferrit”<br />

Rowe will join their staff as<br />

product specialist. One of Rowe’s<br />

first duties will be providing<br />

hands-on training for operation<br />

of EAW’s new UMX-96 largeformat<br />

digital mixing console;<br />

he will also develop curriculum<br />

and presentations for company<br />

educational programs.<br />

Prior to EAW, Rome worked<br />

for several years as the head of<br />

audio technical services for the<br />

Las Vegas branch of Production<br />

Resource Group (PRG). He has<br />

also freelanced as a monitor<br />

engineer for the Cranberries and<br />

as a system technician for Mötley<br />

Crüe, in addition to working on<br />

myriad Las Vegas productions.<br />

“It’s an exciting time to come<br />

aboard as a member of the EAW<br />

Martyn Rowe<br />

Courtesy of EAW<br />

team,” says Rowe. “There’s a<br />

congregation of veteran pro audio<br />

talent that is firmly committed<br />

to truly serving the pro audio<br />

industry in terms of technological<br />

innovation combined with indepth<br />

support, such as a deep<br />

commitment to education, to<br />

back it up.”<br />

www.stage-directions.com • <strong>May</strong> 2007 13

Tools Of The Trade<br />

<strong>May</strong> MélangeThe rise in temperature<br />

Wybron Transition<br />

T h e W y b r o n , I n c .<br />

Transition, a CMY Fiber<br />

Illuminator, uses similar<br />

CMY dichroic color mixing<br />

technology to Wybron’s<br />

Nexera lighting fixtures. The<br />

Transition offers smooth color<br />

changes with nearly infinite<br />

color choices and silent operation. The advantage of using fiber<br />

optics is that the light source is separated from the light output,<br />

and its fiber optic strands do not conduct UV radiation, all of<br />

which is meant to allow practically heatless illumination.<br />

The Transition allows the fiber common ends to remain cool,<br />

and the unit will not burn PMMA fiber. It has a compact design<br />

that measures less than 6 inches wide and weighs just less than<br />

8 pounds. The Transition includes an integral electronic ballast<br />

and power supply. It uses a 150-watt compact UHI light source<br />

and has a 10,000-hour lamp life. It accepts 17 through 34 mm<br />

common end fiber bundles and is RDM compliant. The Transition<br />

can be placed in an accessible location for easy maintenance.<br />

www.wybron.com<br />

QSC SC28 System Controller<br />

The QSC SC28 System Controller is a two-input, eight<br />

output DSP controller that additionally offers user-adjustable EQ<br />

and delay.<br />

The SC28’s<br />

audio quality is<br />

rooted in 48 kHz,<br />

24-bit A/D and<br />

D/A conversion<br />

technology with 32-bit, floating-point DSP offering wide dynamic<br />

range and low distortion. System tunings can be selected by<br />

scrolling through a list of QSC loudspeakers found on the SC28’s<br />

front LCD panel and selecting the desired configuration.<br />

Once the SC28 has been configured to match a system, integral<br />

six-band parametric equalization can be added along with high<br />

and low shelving filters and signal delay. Password protected to<br />

deter unauthorized tampering, the SC28 also provides thermal<br />

and excursion loudspeaker protection, as well as a channellinking<br />

feature that can be used to select linked or independent<br />

control of stereo channel settings. www.qscaudio.com<br />

ETC SmartFade ML<br />

ETC’s new SmartFade ML is a compact, portable and easyto-use<br />

board. The<br />

SmartFade ML<br />

is intended for<br />

small touring acts,<br />

schools, house of<br />

worship venues,<br />

industrials and<br />

other applications.<br />

SmartFade ML brings professional features like palettes,<br />

parameter “fan” and built-in dynamic effects to novice or<br />

experienced users. Its direct-access style of operation means that<br />

Photo Courtesy of Wybron<br />

Photo Courtesy of QSC<br />

Courtesy of ETC<br />

students, volunteers, non-technical staffers and others will be<br />

able to use the console.<br />

With a capacity for up to 24 moving lights and an additional<br />

48 intensity channels (dimmers), and the ability to patch to<br />

two universes of DMX512A (1,024 outputs), SmartFade ML<br />

provides control for smaller lighting rigs. www.etcconnect.com/<br />

SmartFadeML<br />

Look Solutions and City Theatrical Wireless DMX-it<br />

The Wireless DMX-it, by Look Solutions and City Theatrical,<br />

i s a n a c c e s s o r y<br />

d e s i g n e d t o m a k e<br />

any Look Solutions<br />

fog or haze machine<br />

WDS-ready; also, City<br />

T h e a t r i c a l ’s W D S<br />

wireless technology<br />

can control any Look<br />

Solutions product from<br />

their DMX console without DMX cables.<br />

The Wireless DMX-it has a built-in WDS receiver and two<br />

control output jacks: a 1 /8-inch Mini, to control Look Solutions’<br />

Tiny-Fogger or Tiny-Compact, and a 3-pin XLR to control a<br />

Power-Tiny, Viper NT or Unique2. A 5-pin XLR DMX Out is also<br />

included, allowing the unit to function as a conventional WDS<br />

DMX Receiver while simultaneously controlling a fog machine.<br />

looksolutionsusa.com<br />

Clear-Com Tempest<br />

The Clear-Com<br />

Tempest 2400<br />

a n d Te m p e s t<br />

900 is a wireless<br />

intercom system<br />

that has been<br />

continues to usher in a diverse<br />

array of new products.<br />

engineered to<br />

avoid the need<br />

for licensing and<br />

frequency coordination. Utilizing Frequency Hopping Spread<br />

Spectrum (FHSS) in conjunction with TDMA technology, Tempest<br />

operates in both the 2.4 GHz and 900 MHz bands.<br />

Tempest is intended to serve as a solution for the dilemma<br />

wireless communication system users will face when the DTV<br />

transition is completed in early 2009. Tempest operates in the<br />

unlicensed 2.4 GHz and 900 MHz bands, so it is unaffected by the<br />

reallocation of the UHF-TV spectrum. 2xTX Transmission Voice<br />

Data Redundancy sends each packet of audio data twice on<br />

different frequencies and through different antennas.<br />

Tempest can interoperate with other Clear-Com intercom<br />

systems, as well as those from other manufacturers through fourwire<br />

and two-wire connections. Each base-station can operate<br />

up to five wireless belt-stations.<br />

A Shared-Slot feature allows one of the five belt-stations slots<br />

to be used for up to 25 half-duplex, single transmit belt-stations.<br />

The new system has a PC-based control panel, with set-up and<br />

programming transferred to belt-stations via Ethernet or a USB<br />

connection. www.clearcom.com<br />

Courtesy of City Theatrical<br />

and Look Solutions<br />

14 <strong>May</strong> 2007 • www.stage-directions.com

Vital Stats<br />

By Kevin M. Mitchell<br />

Hoosier<br />

Journeyman<br />

Based in Indianapolis, lighting<br />

designer Ryan Koharchik flexes his<br />

craft at a number of venues. Just<br />

don’t ask him to fill out paperwork.<br />

From IRT’s production of A<br />

Midsummer Night’s Dream<br />

Current Home: Indiana Repertory Theater, Indianapolis<br />

About the Organization: The IRT was founded in 1972, and since 1980 has occupied<br />

a 1927 movie house that was renovated to feature three stages (Main, Upper and<br />

Cabaret). The Main <strong>Stage</strong> is a proscenium-style theatre, seating around 620, and the<br />

upper stage, a three-quarter thrust, Ryan seats Koharchik 315. The IRT typically puts on nine shows a<br />

season.<br />

Moonlights At: Indianapolis Civic Theater, the Gregory Hancock Dance Theater and the<br />

ShadowApe Theatre Company, which he co-founded.<br />

Schooling: Koharchik holds an MFA in lighting design from Boston University and a BS<br />

in theatre design from Ball State University.<br />

Recent Work: Beauty and the Beast, Driving Miss Daisy, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Most<br />

Valuable Player and The Turn of the Screw.<br />

Up Next: Twelfth Night.<br />

From IRT’s production<br />

of Turn of the Screw<br />

His Approach to the Work: “I like to meet with the whole creative team and talk about<br />

the script. I don’t like the word ‘concept’ because it’s limiting after a while and can<br />

hinder the creative process. But I like to come up with ideas, impressions and ways to<br />

tell the story as a group.”<br />

Tools of the Trade: ETC lights run by ETC Obsession.<br />

ALL PHOTOS COURTESY OF RYAN KOHARCHIK<br />

On Moving Lights: “I love moving lights, but they can become burdensome. They are<br />

great for musicals and shows that require a lot of scenery, but they do become very<br />

loud, which is difficult to deal with.”<br />

Favorite Part: “I love the beginning because it’s most creative. You work with others<br />

and make ideas concrete. And I love the end — the tech process — from focus on to<br />

opening. I must admit the drafting, paperwork, data entry… if I had enough money to<br />

pay people to do it, I would.”<br />

www.stage-directions.com • <strong>May</strong> 2007 15

Light On The Subject<br />

By Andy Ciddor<br />

The Right<br />

Profile<br />

Why are profile spots so different in the U.S.<br />

as opposed to the rest of the world?<br />

One of North America’s most widely used ellipsoidal<br />

spots is the basic fixed focus Altman 360Q.<br />

Selecon’s Rama 150 PC is an example<br />

of a spot fixture that’s popular abroad.<br />

The ETC Source Four is another very popular<br />

ellipsoidal spot used in North America.<br />

Globalization has been bulldozing its inexorable path<br />

through the world of theatre since Genghis Kahn decided<br />

to take his European vacation. Wandering about<br />

backstage in any vaguely modern performance space anywhere<br />

in the world, most of the equipment will seem familiar to you.<br />

But only at first glance.<br />

You may well see your favorite brands of dimmers, consoles<br />

and luminaires, but look more closely — you are likely to find<br />

some surprising differences. Some of the ellipsoidal reflector<br />

spots (known in other parts of the English speaking world as<br />

profile spots) may have a zoom focus knob on the lens barrel,<br />

and some of the Fresnel spots may actually have smooth (plano<br />

convex) lenses rather than the stepped lens you were expecting.<br />

While not entirely absent from North American equipment<br />

inventories, these variations are not very common in the U.S.<br />

In Historical Context<br />

The plano-convex spot (known in some places as a focus<br />

spot) was in common worldwide use in the early 20th century.<br />

Like today’s Fresnel spots, these luminaires used a spherical<br />

reflector to capture some of the light from the lamp and send<br />

it forward through a lens that allowed the beam to be focused<br />

onto the stage. At that time, the lens was a simple plano-convex<br />

lump of moderately heat-resistant glass, and the lamp was likely<br />

to have a cage or drum-shaped filament.<br />

The combination of the comparatively crudely made lens<br />

with a filament that lay anywhere but on the focal plane of the<br />

optics produced a vaguely rectangular blob of light with dark<br />

and light bands due to the structure of the filament. Moving<br />

the lamp and reflector within the fixture enabled some variation<br />

in the size of the beam and the sharpness of the striations.<br />

The uneven output pattern from these plano-convex (PC) spots<br />

made them particularly difficult to blend together to get an<br />

even stage wash.<br />

It should come as no surprise to learn that the lighting industry<br />

was anxious to find a better instrument than the PC spot.<br />

Developments took two directions. The first approach, taken by<br />

Levy and Kook, was to build a more efficient and accurate optical<br />

system using an ellipsoidal reflector and a grid filament lamp,<br />

which provided a more even beam of light through the PC lens.<br />

The beam was sufficiently flat that it projected a crude profile<br />

of any object placed at the right point in the beam. Thus arose<br />

the Leko ellipsoidal reflector spot (ERS), or profile spot, whose<br />

descendents would be fitted with shutters, irises and gobos.<br />

The other tactic for dealing with the PC spot’s main imperfection<br />

was to use a fuzzier and less accurate lens to remedy<br />

the uneven beam. The Fresnel lens, with its molded-in “imperfections”<br />

and its inaccurate focus due to the stepped rings,<br />

turned out to be ideal. The more diffuse beam was less striated<br />

and much easier to blend into even coverage. The shorter<br />

focal length of the Fresnel lenses also brought with it a wider<br />

range of beam angles. Although cost was initially a barrier to<br />

its widespread adoption, once manufacturing processes were<br />

improved, the Fresnel spot drove the PC spot to virtual extinction<br />

by the middle of last century. The archeologically inclined<br />

reader may be able to find a few dead PC spots (usually with a<br />

big crack in the lens) buried in the equipment graveyards under<br />

the stages and in the back corners of the equipment stores in<br />

older performing spaces.<br />

The States Versus Abroad<br />

Since its introduction, the ERS has been the subject of much<br />

research and development effort. The reflector system has been<br />

redesigned several times to collect more light and to focus it<br />

more sharply. A variety of lamps, featuring higher outputs and<br />

better filament arrangements, have been developed. In different<br />

efforts, the lens system has been both simplified for higher<br />

efficiency and made more complex by introducing zoom focus.<br />

The projection capabilities have been vastly improved through<br />

the addition of condenser optics before the gate, while the<br />

gate itself has been fitted with a vast variety of shutter systems,<br />

including a second set of offset blades to allow for both soft<br />

and hard focused edges. Despite all of these possibilities, North<br />

America’s most widely used ellipsoidal spots remain the basic<br />

fixed focus Altman 360Q and the fixed focus models of the ETC<br />

Source Four.<br />

The situation in the 200V+ regions (i.e., Asia, Africa and<br />

Europe) has been almost the complete reverse. Since the CCT<br />

Silhouette, a zoom-focusing quartz-halogen powered profile<br />

spot, first appeared in the UK in the early 1970s, there has been<br />

almost no interest in the fixed focus variety. So little interest, that<br />

even the world’s most popular ellipsoidal, the ETC Source Four,<br />

only became popular in the 200V+ regions after a range of zoom<br />

focusing models were introduced.<br />

16 <strong>May</strong> 2007 • www.stage-directions.com

Why the Difference?<br />

There has been much gnashing of teeth and pounding of<br />

café tables and bars over why these differences have arisen. The<br />

fixed focus fanatics base their fervor on the higher output and<br />

sharper focus possible with the simpler optics of their favored<br />

fixture. The zoom focus acolytes believe that the additional<br />

flexibility offered by the wider range of beam angles justifies<br />

the marginal light loss, the higher weight and higher price of<br />

their choice. One particularly hurtful (but valid) comment from<br />

the fixed beam camp is that, in many installations, the front-ofhouse<br />

rig is immutable because of a venue’s structure, and so<br />

nullifies any possible benefit from zoom optics.<br />

There may be other, less clearly identified forces at work,<br />

however. In most of the world, a luminaire is seen as a long-term<br />

investment that may not be replaced for 15 to 25 years, so buying<br />

the most flexible unit possible is seen as a measure of futureproofing<br />

the investment. Equipment upgrade and replacement<br />

cycles tend to be much shorter than this in the U.S., particularly<br />

when the inventory belongs to a commercial enterprise.<br />

In the same way that continental drift has separated the continents<br />

and allowed differing evolutionary paths for related species<br />

of animals and plants; so, too, has supply voltage difference<br />

isolated the two branches of luminaire development. Ohm’s<br />

law makes it quite clear that if you halve the voltage to a device<br />

(230V to 110V), you will need twice the current to produce the<br />

same amount of power (approximately 4 amps per kilowatt at<br />

230V and 8 amps per kilowatt at 110V).<br />

What Ohm’s law doesn’t tell you is that a 100V+ lamp is<br />

almost 10 percent more efficient than<br />

its 200V+ equivalent, due to increased<br />

heating efficiencies in the heavier filament.<br />

It also neglects to mention that<br />

the thinner filament is much more fragile<br />

or that the insulation required for<br />

200V+ devices is substantially heavier<br />

and more expensive than that required<br />

for 100V+. There may be 200V+ and<br />

100V+ versions of many lamps, but they<br />

are by no means equivalents in terms of<br />

filament size, robustness or efficiency.<br />

It was only quite recently, when voltage-independent<br />

switching power supplies<br />

became standard on some moving<br />

lights, that it was possible to make a<br />

luminaire that would work wherever in<br />

the world it was plugged in.<br />

The Altman 360Q probably didn’t<br />

make it in the 200V+ regions because<br />

there was no decent lamp available for<br />

it and because it came with 110V insulation<br />

that could not be approved by<br />

electrical authorities. Similarly, CCT was<br />

so busy building Silhouette luminaires<br />

to run at 200V+ that no effort was made<br />

to develop a 100V+ version. Even in this<br />

time of galloping globalization, only a<br />

handful of theatrical luminaire manufacturers<br />

set out to build products that<br />

can work across the entire voltage and<br />

regulatory spectrum.<br />

While one evolutionary branch of the<br />

plano convex spot may have become the Fresnel spot in most<br />

of the world, in Europe in the early 1980s, Fresnel lens technology<br />

was used to craft a hybrid lens. This is a kind of back-cross<br />

between the original ground and polished plano-convex lens<br />

and the molded Fresnel lens. Variously known as a prism convex<br />

or pebble convex lens, this variation has some knobby features<br />

molded onto what was previously the flat surface of the PC lens.<br />

The intention is to remove the unevenness of the original PC’s<br />

beam without losing its sharp focus. The result lies somewhere<br />

between an ellipsoidal and a Fresnel spot. Some less charitable<br />

critics of the result have observed that it combines the worst<br />

characteristics of both. While many LDs will use this luminaire<br />

for specific applications, such as tight stage pools, their use in<br />

the professional industry is not widespread. Nevertheless, most<br />

200V+ theatrical Fresnel manufacturers also offer a PC variant<br />

of their products.<br />

Nigel Levings, the 2003 Tony Award-winning lighting designer<br />

(La Boheme) who works in venues and productions on both<br />

sides of the Atlantic, gets to have the final to say on the subject.<br />

“From time to time, I have been forced to use PCs in repertory<br />

rigs, but I don’t like them much, “ he admits. “I see them as a lazy<br />

substitute for those who can’t calculate beam coverage. My rigs<br />

these days are mostly S4 fixed beam profiles (ERS) with various<br />

frosts and PAR cans.” I guess that this argument will probably<br />

continue in the bar after tonight’s show.<br />

Andy Ciddor has been involved in lighting for nearly four decades<br />

as a practitioner, teacher and technical writer.<br />

www.stage-directions.com • <strong>May</strong> 2007 17

Sound Design<br />

By Bryan Reesman<br />

What I Did For<br />

At a time when glitzy, big budget productions dominate<br />

Broadway, the revival of Michael Bennett’s Pulitzer Prizewinning<br />

A Chorus Line is a welcome breath of fresh air. The<br />

current producers of this high energy, character-driven show even<br />

kept the show’s original 1970s look and musical vibe intact to<br />

present its timeless tale of a group of aspiring chorus line singers<br />

and dancers auditioning for a demanding but personable director.<br />

The staging is simple, with the actors being the focus, and the<br />

director’s voice generally emanating from offstage. The one visually<br />

dazzling element is the mirrored wall that occasionally is used<br />

to give the audience a sense of the performers’ perspective.<br />

The new Chorus Line features sound design by Tom Clark of<br />

Acme Sound Partners, and the live mixer is long-time Broadway<br />

veteran Scott Sanders, who spent seven years on Les Misérables<br />

and recently tackled Chitty Chitty Bang Bang and Hot Feet. During<br />

a break in his busy production schedule, he chatted about working<br />

on this classic show, which had a profitable run at the Curran<br />

Theater in San Francisco last summer, and which reportedly made<br />

back its $8 million budget on Broadway in 18 weeks — a new<br />

record.<br />

<strong>Stage</strong> <strong>Directions</strong>: A Chorus Line is more stripped down compared<br />

with the other stuff you’ve worked on recently.<br />

Scott Sanders: This one’s really simple. The original production<br />

was foots and shots. I think they had five foots and three<br />

or four shots. There are no sound effects; there is very little happening,<br />

and the band takes care of itself for the most part, unlike<br />

Hot Feet, where I was constantly mixing the band. Having no<br />

sound effects and being based on a lot of monologues, it’s pretty<br />

straightforward.<br />

Which console are using?<br />

A DiGiCo D5T. I’d say we’re using about 90 to 100 inputs. We’ve<br />

got duplicate wireless for the cast. We’ve got 20-some wireless<br />

mics to start the show; then we have another set of 17 that we use<br />

for the finale costumes. So for the quick change, there’s a transmitter<br />

already rigged into the gold costumes. There are 40-some<br />

inputs and wireless inputs just there, and then there are another<br />

60 in the 18-piece band.<br />

Which mics are you using on the actors?<br />

We’re using Sennheiser SK-5012 transmitters with the DPA<br />

4061 microphones. The one tough challenge in this show was the<br />

fact that the director was adamant that he didn’t want to see any<br />

wires, so we sort of stepped back a generation and almost everybody<br />

is rigged on their chest.<br />

I recall when one of the actors put her hands together, I could<br />

hear a little bit of a thud.<br />

Yeah, everybody seems to like to touch their heart when they<br />

say something about themselves. That’s about where most of the<br />

women are wearing them, right in the seam of their bra, and the<br />

men are wearing them in various positions on their shirt, in a lot of<br />

cases, underneath the shirt. We found the DPA works surprisingly<br />

well there, even if it’s covered by fabric. We use a lot of high boost<br />

caps, more than any other show I’ve ever done. Typically, when<br />

you’ve got mics on their head, you don’t need the high boost. We<br />

found that the high-boost cap on the people with it in their clothing<br />

gives not only a little more high-end articulation, but because<br />

the windscreen is flat, it also gets less fabric noise.<br />

So this show is high-tech but old school at the same time.<br />

It’s like going backwards. Fifteen years ago, when people realized<br />

that if you put mics on actors’ heads you could solve a lot of<br />

problems and get so much better quality, they stopped putting<br />

mics on people’s chests. But here it was the only way to do it<br />

because of the shorter haircuts. There are three women who do<br />

have it on their heads. The woman who plays Diana wears it on<br />

her head the entire show, and for the other two women who wear<br />

it on their heads, it changes over to a chest position during the<br />

18 <strong>May</strong> 2007 • www.stage-directions.com

Theater Spotlight<br />

Sound<br />

The challenges of microphone placement — foot<br />

and head — figures prominently into the current<br />

Broadway revival of A Chorus Line.<br />

Cassie dance and monologue, because the problem during the<br />

second half of the show is that they start playing with their hats.<br />

So if we had left those head mics on, we would’ve probably lost<br />

those two voices due to hat noise. We don’t have a great mic position,<br />

but I think with all the EQs that Tom put on people and the<br />

tuning of the system, they did a good job for what we were put up<br />

against. It wasn’t our choice to not have mics on people’s heads,<br />

but it still sounds clear, and because of all the delay changes we<br />

keep it pretty fairly well imaged to the stage, as long as they give<br />

me enough source to image.<br />

Is anyone double miked?<br />

No, because the leotards are so small. In fact, most of the<br />

women are wearing the pack itself in the bra, and most of the<br />

men are wearing their packs in their dance belts. A couple of the<br />

women wear it in the back portion of their bodies because they’re<br />

not comfortable with that in their bra.<br />

You have a separate mic for the director when he leaves the<br />

stage and goes to the back of the theatre, correct?<br />

I use that like any other wireless microphone. I only bring it up<br />

when he speaks. Then there’s one regular mic backstage, where<br />

he does his final speech. It’s just an SM58, like the one he sits in<br />

front of when he goes to the back of the theatre. I only use his<br />

wireless when he’s onstage. Otherwise, he’s right in front of me,<br />

at the very back of the house in one of the last two seats, behind<br />

a pillar.<br />

Was there live sound in the original production that ran from<br />

1975 to 1990?<br />

Yes. In fact, my mentor was Otts Munderloh, who was the<br />

designer that I first worked for when I came to Broadway, and he<br />

was the original sound man on this show. That was one of the<br />

turning points for me in taking the job. It was a nice circle for me<br />

because he’d been the original mixer. I’m not sure what they used<br />

back then, but he described it as dials, so the first console they had<br />

must have been a radio static dial of some fashion. I think that it<br />

had more dials than faders. As a matter of fact, a lot of the blocking,<br />

which is still true in our production, came from the necessity<br />

of the foot mics. When Sheila first has her conversation with Zach,<br />

and he asks her to step downstage, she takes a diagonal step to<br />

her right — that was originally to get her in front of foot two. For<br />

a lot of the blocking, where you see them step from the line and<br />

head to a certain place, there were five various sections along the<br />

front of the stage that they utilized. So when they were primarily<br />

singing a lot of their solo work, they were dead center in front of<br />

one of the foot mics.<br />

Do you have foot mics this time?<br />

We’re using some DPA mics with boundary mounts, but that’s<br />

only for emergencies. We have three total, but because we don’t<br />

have anybody double packed. If I lose somebody, it’s the only way<br />

the band would know that they were still singing. The center foot<br />

is the most important one, and it goes pre-fader down to the band<br />

because they’re in the basement in a room called “the bunker”<br />

with a double sheet rock wall with soundproofing, installation<br />

and air-conditioning. It’s a whole isolated room that, if I didn’t<br />

have any mics there, you wouldn’t know there was a band in the<br />

building. It’s that isolated. So if I were to lose somebody’s mic, the<br />

conductor wouldn’t know where the hell he was. I have the center<br />

mic pre-fade going to the Aviom mixers downstairs, so he’s always<br />

getting something from the stage. The only other times I’ve used<br />

them have been when Diana’s mic went dead a couple of times<br />

during “What I Did For Love.” Thank God the blocking was the<br />

way it was, because she stepped downstage to sing most of the<br />

big part of the number and was standing right in front of mic two.<br />

That worked out pretty well.<br />

Bryan Reesman is a New York-based writer who has been published in<br />

the New York Times, MIX, Billboard, and FOH.<br />

www.stage-directions.com • <strong>May</strong> 2007 19

Theatre Spotlight<br />

By Karyn Bauer-Prevost<br />

Molière’s Legacy<br />

all photos courtesy of Comedie Francaise<br />

The façade of the Comedie Francaise<br />

After nearly 400 years, the Comédie Française is more than just<br />

France’s oldest theatre — it’s an institution.<br />

Affectionately referred to as the “Française,” with a capital “F”,<br />

the Comédie Française remains, after almost four centuries<br />

of brilliant performances, dramatic failures, internal battles<br />

and popular successes, France’s foremost cultural beacon. With<br />

nearly 400 employees on the roster, three distinct theatres and an<br />

amazing performance schedule, the Française is more than just a<br />

theatre; it is an institution that holds its own amid the 150 working<br />

theatres in Paris.<br />

The Comédie Française is composed of the historic 18th century<br />

Salle Richelieu, located at the Palais Royal, a luxurious marble<br />

and red velvet lined Italian-style theatre where 900 spectators can<br />

admire the chair where Molière pronounced his last words in Le<br />

Malade Imaginaire; the Théâtre du Vieux Colombier, whose bare<br />

stage was designed for performances without sets and, with its 300-<br />

person seating capacity, was acquired in 1993; and the smallest of<br />

“Ours is an ancient company. It<br />

is also contradictory, passionate<br />

and fragile.” — Denis Podalydès<br />

the three, the 100-seat Studio Théâtre, built in 1996 in the basement<br />

of the Carrousel du Louvre shopping plaza, providing for a most<br />

intimate, if technically complicated, setting.<br />

On any given week, from September through the end of July,<br />

the audience can enjoy five different performances, with three<br />

different shows at the Salle Richelieu alone. Actors are required to<br />

juggle roles among the three theatres and are often required to<br />

perform three times in one day, starting with a matinee at the Vieux<br />

Colombier, an early evening performance at the Studio Théâtre and<br />

ending with a role at the Salle Richelieu.<br />

“They must be very versatile,” says company administrator<br />

Isabelle Baragan. “It is a very demanding schedule.”<br />

Mandated in Versailles in 1680 by King Louis XIV, the original<br />

company, under the direction of Molière, functioned as an independent<br />

unit, with actors surviving on profits from ticket sales. The<br />

better the performances, the greater the crowds, the higher the<br />

pay. Despite heavy government funding covering nearly two thirds<br />

of operating costs, France’s only permanently salaried theatrical<br />

company has maintained its 17th century philosophy.<br />

The company works under the direction of an administrateur<br />

général, appointed by the French Minister of Culture, who selects<br />

the season’s performances, their respective directors and hires<br />

new actors. The new actors are hired for a two-year trial period as<br />

pensionnaires. They are then judged annually by a jury of their peers,<br />

known as the comité, who can promote them to the coveted level of<br />

sociétaire, providing them with a 10-year renewable contract, profit<br />

dividends and tremendous pride. Currently, there are 60 members<br />

of the company, of which 37 are sociétaires and 23 pensionnaires.<br />

“Despite the monetary progression,” adds Baragan, “it is a great<br />

honor to be recognized by a jury of your peers. Becoming a sociétaire<br />

allows an actor to become a member of a very elite and prestigious<br />

company. They carry on a 400-year-old tradition.”<br />

The six-member jury, known as the comité, is also responsible<br />

for firing actors at any level. The ax can fall, without warning, at any<br />

time. Both pensionnaires and sociétaires can have their contracts<br />

revoked, provoking anger and fury. Some may fall back on lawyers<br />

to defend their status.<br />

“Ours is an ancient company,” says sociétaire Denis Podalydès,<br />

director of the hugely successful Cyrano de Bergerac. “It is also contradictory,<br />

passionate and fragile.” The election process is severe<br />

and inflicts hostility, but prevents stagnation, keeping this otherwise<br />

permanent company in constant flux.<br />

Three theatres and an impressive production schedule allow<br />

20 <strong>May</strong> 2007 • www.stage-directions.com

“One false move can provoke<br />

a dramatic domino effect of<br />

hazards.” — Nicolas Fralin<br />

the Française to offer diverse fare, from Racine and Corneille to Pier<br />

Paolo Pasolini’s Orgie and Nathalie Sarraute’s For Yes or No, to its<br />

enthusiastic audiences. Nine hundred yearly performances attract<br />

nearly 350,000 theatregoers in Paris alone. Thanks to private funding<br />

by the Pierre Bergé Foundation, the Jacques Toja Foundation,<br />

the Crédit Agricole Bank and the Accor Groupe, The Française can<br />

export such ambitious productions as the Fables de la Fontaine,<br />

staged in 2005 by Robert Wilson and headed for the Lincoln Center<br />

Festival in July 2007.<br />

For Nicolas Fralin, chief production manager for the three<br />

theatres, the heavy programming schedule at the Salle Richelieu,<br />

known as alternance, is a source of daily headaches. “It is so complex,”<br />

he says, “that one false move can provoke a dramatic domino<br />

effect of hazards.”<br />

The Salle Richelieu boasts a staff of 150 stage technicians. The<br />

flies are equipped on a permanent basis with sets for four different<br />

productions. At the Salle Richelieu, a production is never performed<br />

consecutively. At 8:30 a.m., a team dismounts the sets from the<br />

prior evening. They then install decor for the play in preparation.<br />

At 1:00 p.m., the actors begin rehearsing, and at 5:00 p.m., another<br />

technical team installs the sets for yet another different evening<br />

performance.<br />

In addition to the ETC Congo lighting console that was installed<br />

last year, one of the more recent production improvements that<br />

has eased the load for Fralin came in 2005, when the sound<br />

technicians were provided with a discreet and<br />

open position on the level of the second balcony.<br />

Until then, the sound engineers had been<br />

working behind a glass panel on the third balcony,<br />

thwarting their ability to properly control<br />

sound quality.<br />

When, in February 2007, the company performed<br />

Bernard-Marie Koltès’ Return to the<br />

Desert, under the direction of sociétaire and<br />

now Administrateur Général Muriel <strong>May</strong>ette,<br />

Fralin was faced with a predicament. He was<br />

The motto of the Comédie Française — “Simul et singulis,” which means<br />

together while alone<br />

required to install a wall stage center capable of moving to different<br />

levels smoothly and quietly throughout the performance, but<br />

he did it without fail. “It was complicated,” he says. “It required a<br />

special set of pulleys, maneuvered by the flies, which insured its<br />

smooth movement.”<br />

Perhaps last year’s arrival of <strong>May</strong>ette, appointed administrateur<br />

général in July 2006, is most symbolic of the historic Comédie<br />

Française’s efforts to remain resolutely modern. She is the first<br />

woman to hold such a function, the youngest to be appointed and<br />

the first staff sociétaire to be honored with such a promotion.<br />

<strong>May</strong>ette, 43, intends to export her company’s talents more<br />

often, with more demanding traveling time. She also hopes to<br />

bring greater notoriety to her actors, bringing them into the light<br />

of the media “prior to their retirement.” Two days after her official<br />

arrival in the administrative offices of the luxurious 17th century<br />

Salle Richelieu, the most prestigious of the three theatres, she had<br />

the gold letters “Comédie Française” mounted onto the building’s<br />

exterior wall. Until her arrival, the theatre was bare and enjoyed an<br />

elusive, hidden status. Another new era has begun.<br />

Inside the Salle Richelieu<br />

www.stage-directions.com • <strong>May</strong> 2007 21

School Spotlight<br />

By Karyn Bauer-Prevost<br />

Parfait<br />

of Excellence<br />

For more than 30 years, the<br />

Training Center for Professional<br />

Theatre Technicians has been<br />

training France’s finest.<br />

A student works the board for a production in rehearsal<br />

Deep inside the gritty Parisian suburb of Bagnolet lies<br />

a theatrical jewel. Unique in its vocation, and highly<br />

acclaimed for the excellence of its academic offerings,<br />

The Training Center for Professional Theatre Technicians (Centre<br />

de Formation Professionelle aux Techniques du Spectacle, or<br />

CFPTS), has been attracting students from across France for more<br />

than 30 years. Open to both high-school graduates and practicing<br />

technicians, the school is fertile ground where professionals<br />

and amateurs meet.<br />

“It is a crossroads,” says educational supervisor Béatrice<br />

Marivaux. “Our goal is to promote the greatest amount of interaction<br />

among beginners and experts. Students often return to the<br />

school to engage in that rich exchange”.<br />

During an average year, some 200 active professionals will<br />

take time out of their demanding schedules to teach classes here.<br />

The school boasts nine classrooms, five stage facilities, four sound<br />

studios and nine extensive workshops. The incoming professors<br />

are invited on a rotating basis, keeping coursework contemporary<br />

and evolutionary.<br />

Often unaccustomed to working in a classroom environment,<br />

this rotating staff frequently requires assistance from the school’s<br />

in-house team of teachers who, according to Marivaux, “transform<br />

their enthusiasm into academic tools.”<br />

Nearly 1,000 professionals will have taken continuing education<br />

classes at the CFPTS this year, ranging from the more popular<br />

crash course on WYSIWYG Lighting Design and perfecting the<br />

grandMA console to working with the Pyramix Virtual Studio and<br />

understanding Flying Pig Systems. A variety of long-term training<br />

sessions are also available in the areas of theatre administration,<br />

technical direction, staging, rigging, lighting and sound.<br />

The school also prides itself on the diversity of its stage accessory<br />

classes, unique in France, which teach skills that include ironworking<br />

for designing stage jewelry; sculpture for creating masks<br />

and molds; and special effects for mastering onstage fires, explosions,<br />

snow, smoke and indoor fireworks. A variety of safety classes<br />

ensure that technicians function in a low-risk environment.<br />

Housed in a former sawmill factory, the CFPTS opened its<br />

doors in 1974 as a semi-private continuing education center for<br />

theatre technicians, who take classes to perfect their skills, or to<br />

change jobs entirely. It has since evolved, and in 1992 the school<br />

launched the Center for Art Training, otherwise known as the<br />

CFA. Unique in France, the program is open to recent high-school<br />

graduates, ages 18-25 years old. The 50 students admitted into<br />

each academic cycle must pass a written and oral examination,<br />

proving their scholastic level. They must also demonstrate their<br />

motivation by obtaining a two-year paid internship at a local<br />

theatre prior to enrollment.<br />

“If they are struggling to find an appropriate contact,” says<br />

Emmanuelle Saunier, the school’s outreach officer, “then we can<br />

provide them with some guidance, but we prefer to let them<br />

approach the various theatres on their own. It is essential for prospective<br />

students to demonstrate a certain level of enthusiasm<br />

and assertiveness prior to enrolling.”<br />

That assertiveness will be essential to their training throughout<br />

this two-year program as they alternate between six-week<br />

classroom sessions and hands-on work. Not only do interns<br />

receive a minimum salary, but the majority of those students<br />

studying here, whether in the CFPTS or in the CFA, pay no tuition.<br />

Fees, which can be extensive, (880€ Euros for a three-day rigging<br />

class, 17,200 Euros for a nine-month class in sound production)<br />

are covered by the “taxe d’apprentissage,” a French tax requiring<br />

businesses to reinvest a small percentage of their profits into<br />

training centers like the CFPTS.<br />

“We all learned by watching,” says Marie Noëlle Bourcard,<br />

lighting production supervisor at the Théâtre de l’Athénée Louis<br />

Jouvet in Paris, who frequently takes CFA interns under her wing.<br />

“We know how essential it is for theatre technicians to have that<br />

hands-on experience. They develop into an integral part of the<br />

team and are usually hired once their internship ends.”<br />

The post-graduation placement rate for CFA students is nearly<br />

100 percent. Among the prestigious venues where students have<br />

found jobs are the Paris National Opera and the National Theatre<br />

22 <strong>May</strong> 2007 • www.stage-directions.com

photos courtesy of CFPTS<br />

School Spotlight<br />

Students set up before a production<br />

A student works on a mold<br />

of Chaillot, as well as smaller, private-run theatres such as the<br />

Théâtre du Soleil or the Théâtre de l’Athénée.<br />

Degrees in lighting, sound or staging are only issued after<br />

the final exam that focuses on fully coordinating and executing<br />

a production. Students must demonstrate their technical skills<br />

and work as a team, negotiating situations with their peers and<br />

displaying problem-solving skills.<br />

A theatre company, dance troupe or circus act have come<br />

in occasionally, providing students with hands-on material. For<br />

Marivaux, “it is likely the first and only time in their careers that<br />

the actors will be working for the technicians.”<br />

The shows are often riddled with theatrical dilemmas, such as<br />

installing a curtain of rain without runoff or puddles, having an<br />

actor catch flying glasses on various intervals<br />

or creating a lighting atmosphere<br />

similar to one found under a sunlit tent<br />

in the desert. “If our students are asked to<br />

outfit a production in the middle of the<br />

Gobi desert, it is our job to ensure that<br />

they can, with no injuries,” notes Saunier.<br />

A recent production saw a rich collaboration<br />

between the graduating students<br />

of the National Circus School of Bondy,<br />

which allowed students from both sides<br />

of the curtain to work together in what<br />

might be considered a two-tiered final<br />

exam. “Many love stories resulted from<br />

that production,” chuckles Marivaux.<br />

Eric Proust, senior production supervisor<br />

for the annual Festival d’Art Lyrique<br />

in Aix-en-Provence, was among the 1996<br />

jury. “It was fabulous,” he recalls. “We<br />

were observing future technicians at work<br />

and exchanging ideas with fellow experts,<br />

some of whom were even former CFA<br />

graduates.” This 30-year veteran has since<br />

become one of the school’s most enthusiastic<br />

advocates.<br />

Prior to touring with the Théâtre<br />

Vidy-Lausanne’s latest production<br />

of Mademoiselle Julie, performed in<br />

November 2006, Proust enrolled in his<br />

first CFPTS class: Perfecting AutoCAD.<br />

“It was amazing to finally sit down in a<br />

classroom and work with other pros in a<br />

learning environment,” he says. “It is truly wonderful to learn. All<br />

theatre technicians should take classes — how stimulating!”<br />

Next year, Proust will teach his first class, a session on becoming<br />

a theatre administrator. While there, he may cross paths with<br />

Philippe Groggia, chief electrician from the Comédie Française,<br />

who will be teaching an electrical theory class, or perhaps he<br />

will meet Dominique Ledolley, sound operator from the Opéra<br />

Bastille, or art history professor Gérard Delpit from the Louvre<br />

Museum. Together they will be working to forge future talents,<br />

like Samuel Chatain, a young CFA student who is here for one<br />

simple reason: “Because they are the best.”<br />

Karyn Bauer-Prevost is a freelance writer based in Paris.<br />

www.stage-directions.com • Aprilr 2007 23

Theatre Space<br />

By Charles Conte<br />

Victoria Station<br />

ALL PHOTOGRAPHY BY JERRY LAURSEA,<br />

COURTESY OF CITY OF RANCHO CUCAMONGA<br />

An isolated West Coast community<br />

gets a cultural boost thanks to a<br />

new theatre complex.<br />

The exterior of the Victoria Gardens Cultural Center<br />

Interior view of the Playhouse<br />

Along with Timbuktu, Bora Bora and Walla Walla, Washington,<br />

Rancho Cucamonga, a city of some 170,000 42 miles east<br />

of Los Angeles, carries on the proud tradition of bearing a<br />

quirky name that’s guaranteed to make people smile.<br />

Far from hiding its heritage under a bushel, the city of Rancho<br />

Cucamonga embraces it. In 1993, the city erected a statue of<br />

Jack Benny (the comedian used the city name as the punch<br />

line in a running gag on his radio show) outside The Epicenter,<br />

home of baseball’s California Angels Class A affiliate, the Rancho<br />

Cucamonga Quakes. The statue was actually commissioned to<br />

encourage the creation of a performing arts center in the city.<br />

Today, that statue sits in the lobby of the 536-seat Lewis<br />

Family Playhouse, the focal venue of the Victoria Gardens<br />

Cultural Center, along with the Victoria Gardens Library.<br />

Completed in August 2006, the Cultural Center is a major<br />

anchor to the 1.5 million-square-foot Victoria Gardens<br />

retail center.<br />

The city enlisted WLC Architects and Pitassi Architects (both<br />

with offices in Rancho Cucamonga) to interpret the city’s vision<br />

for a facility combining a community-gathering place with a<br />

playhouse and a library. The city wanted to create a place that<br />

inspires, entertains, educates and sparks the imagination. The<br />

architects and the Berkeley Calif.-based design firm, Flying<br />

Colors, Inc., delivered on all counts.<br />

Auerbach Pollock Friedlander collaborated with the architectural<br />

team as theatre, sound, video and communications<br />

consultants. They also provided the design for all of the<br />

theatrical systems. The firm’s architectural lighting design<br />

division, Auerbach Glasow, provided lighting design services<br />

throughout the public spaces.<br />

In the Lewis Family Playhouse, home to the resident<br />

MainStreet Theatre Company, the Auerbach-specified FOH<br />

system is based around a Yamaha M7CL-48 digital audio console<br />

and loudspeaker arrays from NEXO.<br />

The Lewis Family Playhouse<br />

The Lewis Family Playhouse is a flexible proscenium theatre.<br />

As Auerbach’s project manager, Mike McMackin, explains, “A<br />

flexible platform system is configurable for use as a thrust stage,<br />

additional audience seating or as an orchestra pit. In-house side<br />

stages and side balconies provide an extension of the performance<br />

area into the volume of the audience chamber.” The<br />

proscenium opening is 40 feet wide by 22 feet high by 34 feet<br />

deep. The stage is fully trapped to accommodate entrances and<br />

exits from the space below.<br />

Sound system design for the theatre presented a number of<br />

challenges. First of all, the theatre would host a variety of performances:<br />

theatre for young audiences, professional theatre, classical<br />

music, musicals, pops performances and large format DVD<br />

presentations. Secondly, though line arrays were preferred for<br />

delivering the best possible left/center/right image to every seat,<br />

according to Auerbach sound system designer Greg Weddig, “We<br />

struggled with long line arrays, trying to integrate them into the<br />

architecture.”<br />

The NEXO Geo Series presented an interesting solution: their<br />

GEO S830 loudspeaker could be vertically or horizontally mounted.<br />

“Essentially, we turned a vertical line array on its side,” says<br />

Weddig. The center cluster consists of five GEO S830s, with appropriate<br />

(NEXO) processing, each delivering a 30 degree dispersion<br />

pattern. Vertical arrays consisting of three S830s each, left and<br />

right of the proscenium arch, are nearly invisible: the speakers<br />

measure approx. 16 inches by 10 inches by 6 inches.<br />

Two NEXO subs located at catwalk level above and slightly<br />