Download a PDF - Stage Directions Magazine

Download a PDF - Stage Directions Magazine

Download a PDF - Stage Directions Magazine

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Sound Design<br />

By Bryan Reesman<br />

Volley<br />

Paul Charlier<br />

Up<br />

Paul Charlier serves up<br />

his sound artistry in<br />

the Broadway drama<br />

Deuce.<br />

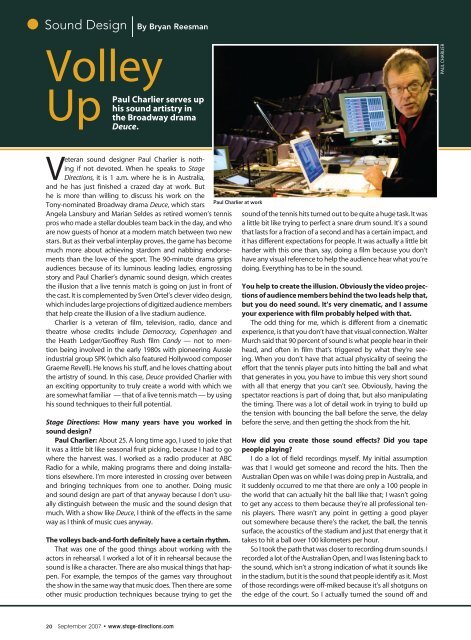

Veteran sound designer Paul Charlier is nothing<br />

if not devoted. When he speaks to <strong>Stage</strong><br />

<strong>Directions</strong>, it is 1 a.m. where he is in Australia,<br />

and he has just finished a crazed day at work. But<br />

he is more than willing to discuss his work on the<br />

Tony-nominated Broadway drama Deuce, which stars<br />

Angela Lansbury and Marian Seldes as retired women’s tennis<br />

pros who made a stellar doubles team back in the day, and who<br />

are now guests of honor at a modern match between two new<br />

stars. But as their verbal interplay proves, the game has become<br />

much more about achieving stardom and nabbing endorsements<br />

than the love of the sport. The 90-minute drama grips<br />

audiences because of its luminous leading ladies, engrossing<br />

story and Paul Charlier’s dynamic sound design, which creates<br />

the illusion that a live tennis match is going on just in front of<br />

the cast. It is complemented by Sven Ortel’s clever video design,<br />

which includes large projections of digitized audience members<br />

that help create the illusion of a live stadium audience.<br />

Charlier is a veteran of film, television, radio, dance and<br />

theatre whose credits include Democracy, Copenhagen and<br />

the Heath Ledger/Geoffrey Rush film Candy — not to mention<br />

being involved in the early 1980s with pioneering Aussie<br />

industrial group SPK (which also featured Hollywood composer<br />

Graeme Revell). He knows his stuff, and he loves chatting about<br />

the artistry of sound. In this case, Deuce provided Charlier with<br />

an exciting opportunity to truly create a world with which we<br />

are somewhat familiar — that of a live tennis match — by using<br />

his sound techniques to their full potential.<br />

<strong>Stage</strong> <strong>Directions</strong>: How many years have you worked in<br />

sound design?<br />

Paul Charlier: About 25. A long time ago, I used to joke that<br />

it was a little bit like seasonal fruit picking, because I had to go<br />

where the harvest was. I worked as a radio producer at ABC<br />

Radio for a while, making programs there and doing installations<br />

elsewhere. I’m more interested in crossing over between<br />

and bringing techniques from one to another. Doing music<br />

and sound design are part of that anyway because I don’t usually<br />

distinguish between the music and the sound design that<br />

much. With a show like Deuce, I think of the effects in the same<br />

way as I think of music cues anyway.<br />

The volleys back-and-forth definitely have a certain rhythm.<br />

That was one of the good things about working with the<br />

actors in rehearsal. I worked a lot of it in rehearsal because the<br />

sound is like a character. There are also musical things that happen.<br />

For example, the tempos of the games vary throughout<br />

the show in the same way that music does. Then there are some<br />

other music production techniques because trying to get the<br />

Paul Charlier at work<br />

sound of the tennis hits turned out to be quite a huge task. It was<br />

a little bit like trying to perfect a snare drum sound. It’s a sound<br />

that lasts for a fraction of a second and has a certain impact, and<br />

it has different expectations for people. It was actually a little bit<br />

harder with this one than, say, doing a film because you don’t<br />

have any visual reference to help the audience hear what you’re<br />

doing. Everything has to be in the sound.<br />

You help to create the illusion. Obviously the video projections<br />

of audience members behind the two leads help that,<br />

but you do need sound. It’s very cinematic, and I assume<br />

your experience with film probably helped with that.<br />

The odd thing for me, which is different from a cinematic<br />

experience, is that you don’t have that visual connection. Walter<br />

Murch said that 90 percent of sound is what people hear in their<br />

head, and often in film that’s triggered by what they’re seeing.<br />

When you don’t have that actual physicality of seeing the<br />

effort that the tennis player puts into hitting the ball and what<br />

that generates in you, you have to imbue this very short sound<br />

with all that energy that you can’t see. Obviously, having the<br />

spectator reactions is part of doing that, but also manipulating<br />

the timing. There was a lot of detail work in trying to build up<br />

the tension with bouncing the ball before the serve, the delay<br />

before the serve, and then getting the shock from the hit.<br />

How did you create those sound effects? Did you tape<br />

people playing?<br />

I do a lot of field recordings myself. My initial assumption<br />

was that I would get someone and record the hits. Then the<br />

Australian Open was on while I was doing prep in Australia, and<br />

it suddenly occurred to me that there are only a 100 people in<br />

the world that can actually hit the ball like that; I wasn’t going<br />

to get any access to them because they’re all professional tennis<br />

players. There wasn’t any point in getting a good player<br />

out somewhere because there’s the racket, the ball, the tennis<br />

surface, the acoustics of the stadium and just that energy that it<br />

takes to hit a ball over 100 kilometers per hour.<br />

So I took the path that was closer to recording drum sounds. I<br />

recorded a lot of the Australian Open, and I was listening back to<br />

the sound, which isn’t a strong indication of what it sounds like<br />

in the stadium, but it is the sound that people identify as it. Most<br />

of those recordings were off-miked because it’s all shotguns on<br />

the edge of the court. So I actually turned the sound off and<br />

20 September 2007 • www.stage-directions.com