Living Architecture Monitor - Green Roofs for Healthy Cities

Living Architecture Monitor - Green Roofs for Healthy Cities

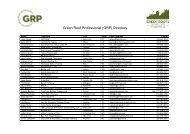

Living Architecture Monitor - Green Roofs for Healthy Cities

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

THEGROWINGMEDIA&PLANTISSUE<br />

“Organic matter breaks<br />

down and goes away; to<br />

replace lost material could<br />

require many trips with<br />

heavy bags up steps or<br />

an elevator.”<br />

Chuck Friedrich<br />

the particles which lighten the load, retain nutrients and water, and<br />

best of all it is permanent. A good quality graded sand as filler is<br />

good <strong>for</strong> stability, and a measured amount of the proper organic<br />

compost provides microbial activity that is beneficial to the biology<br />

of the media. Currently, there are no standards related to the use of<br />

compost on green roofs.<br />

What about fertilizer? Save it <strong>for</strong> planting time. There is absolutely<br />

no reason to add fertilizer to a green roof media during the blending<br />

process. For good reason, in most cases the media is installed<br />

months be<strong>for</strong>e the first plant is installed. There<strong>for</strong>e, why spend<br />

money on fertilizer that will only end up leaching out and down the<br />

drain be<strong>for</strong>e the plants show up on the job? The best method is to<br />

blend a good slow release fertilizer into the top layer of the media<br />

during the planting operation.<br />

Once planted, provide lots of maintenance and irrigation; with that<br />

it can be beautiful and last <strong>for</strong> several decades. I <strong>for</strong>got to mention,<br />

also add lots of money, you get what you pay <strong>for</strong>. If you can keep the<br />

general contractor and schedule in check, the process can actually<br />

go smooth, right? Wrong. Don’t <strong>for</strong>get about the engineer.<br />

AWEIGHTYSUBJECT<br />

I am amazed how the specification on the weight of the media can<br />

be so tight, while in the same specification, the plan calls <strong>for</strong> 14<br />

Oak trees to be planted. It tickles me when I am asked at least<br />

twice per month by designers, “how much does a full grown tree<br />

weigh?” What? Dogwood or Sequoia? Does an additional pound or<br />

two per cubic foot of media, one way or another, make that much<br />

of a difference? I guess it will when 350-pound Aunt Bertha and<br />

the twins decide to have lunch up on the roof.<br />

All kidding aside, weight is an issue, especially on retrofitted extensive<br />

roofs. It is important to design using the saturated weight of the<br />

media. The ASTM Sub-committee <strong>for</strong> <strong>Green</strong> <strong>Roofs</strong> has developed<br />

standards <strong>for</strong> the practice and test methods <strong>for</strong> the determination<br />

almost as absurd to consider all organics to be the same. There are<br />

some organics that I would never use on a green roof (some of which<br />

were used in the research behind the FLL Standard). From cellular<br />

structure to composting process and beyond, organics are far too complex<br />

to generalize within a Standard.<br />

Secondly, the FLL Standard dictates organic content by mass. I can<br />

understand why, since the dominant testing method <strong>for</strong> organic content<br />

is the burn method, which can only measure by mass. However, by doing<br />

so, the Standard leaves a lot open to interpretation. For instance, one<br />

can use an extremely heavy inorganic material to achieve a high percentage<br />

of organic content since organics are generally much lighter. I was<br />

able to achieve organic content of over 60 per cent by volume in the<br />

growing medium but only eight per cent by mass. Was this ambiguity<br />

intended by the Standard?<br />

Interestingly, contrary to what I heard in the industry, the FLL Standard<br />

did allow <strong>for</strong> higher levels of organics. Section 9.2.2 states: “A greater<br />

proportion of organic matter may be required where special <strong>for</strong>ms of<br />

vegetation, such as humus rooting plants, are used.” This shows the<br />

importance of matching the growing medium to the physiological<br />

needs of the plants, another area largely uninitiated by many suppliers<br />

in our industry.<br />

Thirdly, the Standard focused on material specifications instead of<br />

per<strong>for</strong>mance specifications and by doing so, essentially closed the<br />

door on innovation. (It seems the lowly sedum is the order of the day,<br />

matched to equally low per<strong>for</strong>mance mediums). This caused companies<br />

to scramble to find similar products in North America with the<br />

prize going to those who could quickly identify and corner the market<br />

on certain products. As most of the construction industry in North<br />

America makes the change to per<strong>for</strong>mance-based specifications, the<br />

FLL Standard represents a step backward.<br />

Lastly, I concluded the Standard itself was not as much a problem<br />

as people’s interpretation of it. For example; there seems to be much<br />

misunderstanding of what organic content is. One hundred per cent<br />

FORMULATING, TESTING, PLANT<br />

GROWTH TRIALS, PROBLEM SOLVING<br />

“SEND US YOUR<br />

EXTENSIVE/INTENSIVE 5<br />

GALLON PAIL PLEASE!”<br />

SOIL CONTROL LAB<br />

42 HANGAR WAY<br />

WATSONVILLE, CA 95076<br />

(831) 724-5422 PHONE,<br />

(831) 724-3188 FAX,<br />

WWW.GREENROOFLAB.COM<br />

FRANK@COMPOSTLAB.COM<br />

CONTACT: FRANK SHIELDS