BOOTH WHO? - Washington State Digital Archives

BOOTH WHO? - Washington State Digital Archives

BOOTH WHO? - Washington State Digital Archives

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Capitol in March, demanding bigger raises from a projected $400 million revenue windfall.<br />

The buttons depicted Gardner as a smug cheapskate with a “3%” pin on his lapel.<br />

* * *<br />

Gardner’s executive request package was pushing a hundred bills when Heck came<br />

on board. “That’s not the way this can work,” he insisted. “The governor has to be for three<br />

or four big things. Our priorities have to be clear.” Heck was determined to reassert Booth<br />

forcefully into the legislative process. The Cabbage Patch Governor became The Terminator.<br />

Booth shot down nearly 18 percent of the bills that arrived on his desk in 1989, using his<br />

veto a record 83 times. Overall, he vetoed 14 percent of the bills sent to him, more than<br />

Dan Evans in his three terms. Gardner was also more forceful with the veto pen than Dixy<br />

Lee Ray, John Spellman and his successor, Mike Lowry.<br />

Weary after nearly five months of tax reform horse-trading and peeved at Gardner’s<br />

new cheekiness, the 1989<br />

Legislature overrode his veto<br />

of a bill creating a new crime,<br />

residential burglary. The lawmakers<br />

wanted to emphasize the threat<br />

to human life created by a home<br />

invasion. The House vote was 97-0;<br />

the Senate 46-1. Gardner said he<br />

supported the idea, but vetoed the<br />

bill on the grounds that the longer<br />

prison sentences prescribed in the<br />

legislation would strain the budget.<br />

Dan Evans promptly sent him a<br />

letter that Booth had framed. Today it hangs prominently on a wall in his office. “You’re not a<br />

governor,” Evans said, “until you have been overridden.”<br />

Gardner, Heck and Foster had decided to pave the way to an income tax with a plan<br />

that boosted the gas tax and reduced the sales and business-and-occupation taxes. In “Sine<br />

Die,” a fascinating guidebook to the <strong>Washington</strong> legislative process, Edward D. Seeberger<br />

offers the anatomy of the dustup that ensued: “The Senate took politically tough votes to<br />

pass one gas tax increase at seven cents and another at five cents. Gardner let it be known he<br />

would veto both efforts without overall tax reform, so much-relieved House Democrats let the<br />

proposals die. To make up for their earlier tax increase votes, senators passed a transportation<br />

budget with no gas tax increase at all and the House concurred.” The first special session ended<br />

on that note. Although he still lacked a deal, the governor called a second special session. Two<br />

days of arm-twisting made the lawmakers even crankier. Gardner said he would accept a fourcent<br />

increase, “but by then few legislators cared. …Leaders made it known they were prepared<br />

to vote to override six more Gardner vetoes if he called another special session.”<br />

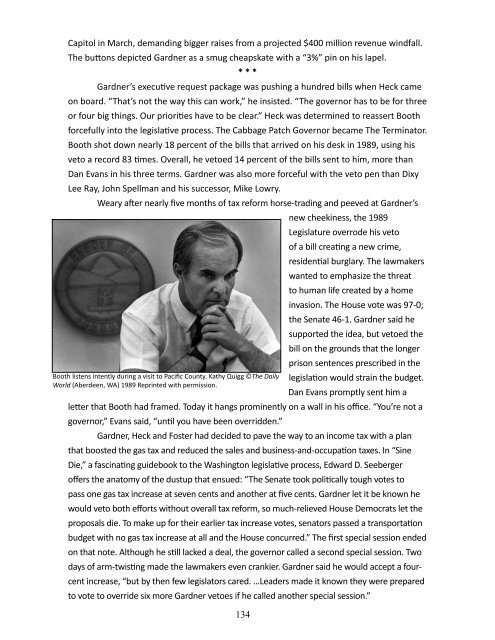

Booth listens intently during a visit to Pacific County. Kathy Quigg ©The Daily<br />

World (Aberdeen, WA) 1989 Reprinted with permission.<br />

134