BOOTH WHO? - Washington State Digital Archives

BOOTH WHO? - Washington State Digital Archives

BOOTH WHO? - Washington State Digital Archives

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

ut the environment pulls the trigger. They didn’t talk much about what ailed Uncle Edwin<br />

back then. It was embarrassing when his hands shook.<br />

Bill Clapp, Booth’s half-brother, let him work on some real-estate projects. It was<br />

a sweet gesture that didn’t come to much because his attention span was spotty. When<br />

Booth learned that depression and anxiety were common symptoms of Parkinson’s, he<br />

was glad he wasn’t just losing his mind. The chemistry of his brain was under attack. “I was<br />

bouncing along at the bottom,” he recalls. “I was dysfunctional. I went four to six weeks<br />

one time without being able to sleep.” The first time he visited a neurologist in Seattle, he<br />

complained that he couldn’t imagine feeling more terrible. “If I keep feeling this way,” he<br />

said, “I don’t think I want to keep on living.” The doctor immediately called a Parkinson’s<br />

specialist who said he could see the former governor immediately. “Can I trust you to<br />

walk over there, or do you want me to take you?” the doctor asked intently. Relieved that<br />

someone understood how desperate he was, Booth said he could make it on his own.<br />

They adjusted his meds. A new drug called Mirapex quickly made him feel dramatically<br />

better for a quite a while. About three weeks after first taking it, he felt “reborn” – “It was a<br />

reawakening,” he said. He took up golf, which was physically and emotionally therapeutic.<br />

Parkinson’s tremors often decrease, even disappear, when major muscles contract under<br />

strenuous movement, so his chip shots had some extra oomph. He became president of the<br />

board of Seattle’s Municipal Golf Association and joined the board of the Seattle/King County<br />

YMCA. He tried to learn to cook, which “didn’t take,” and learned woodworking, which did. He<br />

loved sawing and hammering “because I can see the results of what I do.” Working with power<br />

saws, he joked, also required concentration. His sister Joan was the recipient of one of his first<br />

projects, a handsome table. Other relatives and friends received rockers and clocks. He began<br />

splitting his time between the condo in Seattle and his new basement workshop on Vashon<br />

Island. His loved going to his grandchildren’s games. Gardner also returned to the Central Area<br />

to help revitalize its athletic programs and tutor kids. He joined his old friend Emory Bundy in<br />

opposing Sound Transit’s light-rail expansion plan, asserting that the money would be better<br />

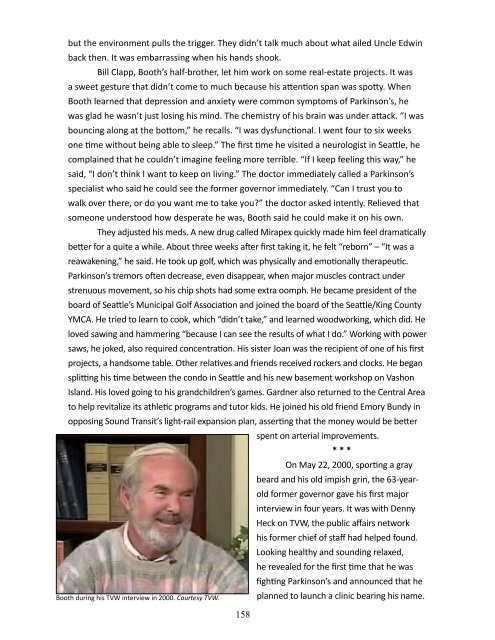

Booth during his TVW interview in 2000. Courtesy TVW.<br />

spent on arterial improvements.<br />

* * *<br />

On May 22, 2000, sporting a gray<br />

beard and his old impish grin, the 63-yearold<br />

former governor gave his first major<br />

interview in four years. It was with Denny<br />

Heck on TVW, the public affairs network<br />

his former chief of staff had helped found.<br />

Looking healthy and sounding relaxed,<br />

he revealed for the first time that he was<br />

fighting Parkinson’s and announced that he<br />

planned to launch a clinic bearing his name.<br />

158