Future of the Gardiner Expressway - Nanos Research

Future of the Gardiner Expressway - Nanos Research

Future of the Gardiner Expressway - Nanos Research

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

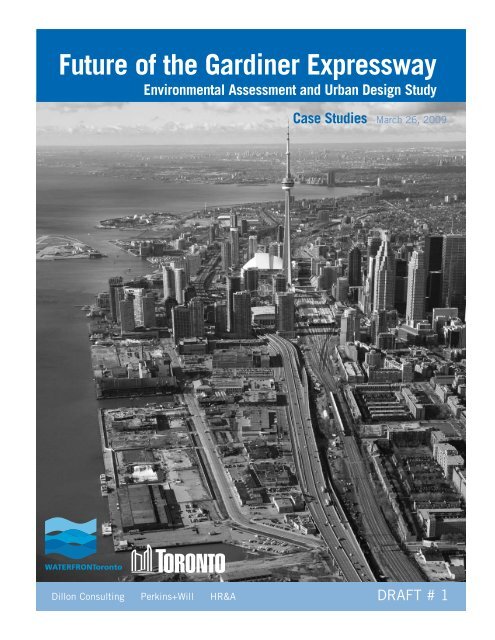

<strong>Future</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gardiner</strong> <strong>Expressway</strong>Environmental Assessment and Urban Design StudyCase StudiesMarch 26, 2009Dillon Consulting Perkins+Will HR&A DRAFT # 1

(This page intentionally left blank.)

ContentsIIntroductionII Scale ComparisionsIII AlternativesIV Computive AnalysisV Case StudiesAlaskan Way Viaduct – Seattle, WAWest Side Highway – New York, NYBonaventure <strong>Expressway</strong> – Montreal, QURiverfront Parkway – Chattanooga, TNEmbarcadero Freeway – San Francisco, CACheonggyecheon <strong>Expressway</strong> – Seoul, KoreaSheridan <strong>Expressway</strong> – Bronx, NYA8ern8 – Zaanstadt, The Ne<strong>the</strong>rlandsViaduct des Arts – Paris, FranceEast River Esplanade – New York, NYBuffalo Skyway – Buffalo, NYWhitehurst Freeway – Washington, DCVI Teasers and Urban BoulevardsVII Summary MatrixVIII Sources

(This page intentionally left blank.)

(This page intentionally left blank.)

ScaleComparisonsSECTION II: Scale comparisons 3

Scale ComparisonsA8ern8• Zaanstadt, The Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands, 0.4 km (0.25 miles)Bonaventure <strong>Expressway</strong>• Montreal, QC, 1 km (0.6 mile)Whitehurst Freeway• Washington, DC, 1.2 km (0.75 miles)Buffalo Skyway• Buffalo, NY, 1.6 km (1 mile)Sheridan <strong>Expressway</strong>• Bronx, NY, 2 km (1.25 mile)Viaduct des Arts• Paris, France, 2 km (1.25 miles)<strong>Gardiner</strong> <strong>Expressway</strong>• Toronto, ON, 2.4 km (1.5 miles)Embarcadero Freeway• San Francisco, CA, 2.5 km (1.6 mile)Riverfront Parkway• Chattanooga, TN, 2.7 km (1.7 mile)East River Esplanade• New York, NY, 3.2 km (2 miles)Alaskan Way Viaduct• Seattle, WA, 3.2 km (2 miles)Cheonggyecheon <strong>Expressway</strong>• Seoul, Korea, 6.1 km (3.75 miles)West Side Highway• New York, NY, 8.2 km (5 miles)0 0.25 0.5 km0 0.25 0.5 mile4<strong>Future</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gardiner</strong> <strong>Expressway</strong>

SECTION II: Scale comparisons 5

Scale Comparisons<strong>Gardiner</strong> <strong>Expressway</strong> – Toronto, ON• Year built: 1965; Length: 2.4 km; Vehicles per day: 120,000Viaduct des Arts – Paris, France – “Ameliorate”• Year built: 1850s; Length: 2 km; Vehicles per day: N / ABuffalo Skyway – Buffalo, NY – “Do Nothing”• Year built: 1966; Length: 1.6 km; Vehicles per day: 43,400East River Esplanade – New York, NY – “Ameliorate”• Year built: 1954; Length: 3.2 km; Vehicles per day: 175,000Whitehurst Freeway – Washington, D.C. – “Do Nothing”• Year built: 1949; Length: 1.2 km; Vehicles per day: 45,000A8ern8 – Zaanstadt, The Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands – “Ameliorate”• Year built: 1970s; Length: 0.4 km; Vehicles per day: N / A0 0.5 1 km0 0.5 1 mile6<strong>Future</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gardiner</strong> <strong>Expressway</strong>

Alaskan Way Viaduct – Seattle, WA – “Replace”• Year built: 1959; Length: 3.2 km; Vehicles per day: 110,000West Side Highway – New York, NY – “Remove / Replace”• Year built: 1937; Length: 8.2 km; Vehicles per day: 140,0000 0.5 1 km0 0.5 1 mileSECTION II: Scale comparisons 7

Scale ComparisonsEmbarcadero Freeway – San Francisco, CA – “Remove”• Year built: 1957; Length: 2.5 km; Vehicles per day: 80,000Bonaventure <strong>Expressway</strong> – Montreal, QU – “Remove”• Year built: 1967; Length: 1 km; Vehicles per day: 55,000Sheridan <strong>Expressway</strong> – Bronx, NY – “Remove”• Year built: 1962; Length: 2 km; Vehicles per day: 40,0000 0.5 1 km0 0.5 1 mile8<strong>Future</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gardiner</strong> <strong>Expressway</strong>

Cheonggyecheon <strong>Expressway</strong> – Seoul, Korea – “Remove”• Year built: 1958-76; Length: 6.1 km; Vehicles per day: 120,000Riverfront Parkway / 21st Century Waterfront – Chattanooga, TN – “Remove”• Year built: 1960s; Length: 2.7 km; Vehicles per day: 20,0000 0.5 1 km0 0.5 1 mileSECTION II: Scale comparisons 9

(This page intentionally left blank.)

AlternativesSECTION III: alternatives 11

The following describes additional alternativesillustrated by <strong>the</strong> 12 case studies. These casestudy alternatives may <strong>of</strong>fer ideas for newunique alternatives or design variations on <strong>the</strong>four initial alternatives.Rebuild• Highway removal studies have beeninitiated when elevated structures havebecome unsafe or damaged ei<strong>the</strong>r bynatural disaster or reaching <strong>the</strong> end <strong>of</strong>useful life. This was <strong>the</strong> case, in particular,after earthquakes in San Francisco andSeattle.Infillsome case studies, however, <strong>the</strong> preferredalternative reduced traffic capacity.In Chattanooga, Tennessee, for example,studies showed that an existing parkwayhad excess capacity. A new boulevard,<strong>the</strong>refore, was designed to accommodatelower traffic volumes than <strong>the</strong> demolishedhighway.• Studies to remove waterfront elevatedstructures have considered <strong>the</strong> opportunityto modify <strong>the</strong> waterfront edge through infill.In <strong>the</strong>se instances, alternatives toreconstruct and reestablish an elevatedhighway’s structural integrity wereconsidered. This alternative maintains <strong>the</strong>“status quo”.Remove Plus• In some case studies, highway removal<strong>of</strong>fered opportunities to create new largescalepublic amenities or reclaimed landfor redevelopment. In Seoul, Korea, forexample, <strong>the</strong> Cheonggyecheon <strong>Expressway</strong>was replaced with a 6-kilometer (3.75miles) linear park.An example is <strong>the</strong> Westway proposal forManhattan’s Hudson River waterfront. Itproposed replacing an elevated highwaywith a tunnel buried underneath infill –<strong>the</strong>reby adding 178 acres <strong>of</strong> new waterfrontland.Air-rights• New construction on elevated highway airrightshas also been considered. Studiesfor <strong>the</strong> East River Esplanade, for example,considered building new residential towersover F.D.R. Drive on Lower Manhattan’seast side.Reduce• A key issue in highway removal studiesis whe<strong>the</strong>r future scenarios shouldaccommodate traffic volumes (vehiclesper daily) at or above existing levels. InSECTION III: alternatives 13

(This page intentionally left blank.)

ComparativeAnalysisSECTION IV: COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS 15

Comparative AnalysisKEY CASE STUDY LESSONS• Solutions come in different shapesand sizes.• Transportation solutions should beseen through <strong>the</strong> lens <strong>of</strong> city-buildingand quality <strong>of</strong> life.• Transportation uses are continuallyevolving – changes in demographics,economics, and lifestyle effect trafficdemand.• Traffic demand can be managed.• Transportation infrastructure <strong>of</strong>fersextraordinary opportunities for design,creativity, and new public realm.• Infrastructure does not have to besingle-purpose or boring.• The public sector must be strategic inorder to capture value <strong>of</strong> investmentsin infrastructure to serve both communityand development goals.• City-building projects <strong>of</strong> this magnituderequire vision and activecommitment at <strong>the</strong> highest levels <strong>of</strong>leadership – mayors, governors, andcity councils. Moreover, <strong>the</strong> full range<strong>of</strong> stakeholder input, from support toopposition, must be understood andresponded to substantively.The <strong>Gardiner</strong> <strong>Expressway</strong> is 2.4 km long (1.5miles) elevated highway. Its construction wascompleted in 1966. The six-lane highway(three lanes in both directions) carries120,000 vehicles per day in <strong>the</strong> area betweenJarvis Street and Leslie Street.The <strong>Gardiner</strong> passes through mostly industrialland on <strong>the</strong> Lake Ontario waterfront. Thearea includes East Bay Front and LowerDon Lands, two precincts currently beingplanned by Waterfront Toronto. A railroadembankment forms a barrier between <strong>the</strong>seprecincts and three medium-density, mixeduseneighborhoods upland – St. Lawrence, <strong>the</strong>Distillery District, and West Don Lands.In terms <strong>of</strong> scale and urban context, <strong>the</strong><strong>Gardiner</strong> <strong>Expressway</strong> is most similar, among<strong>the</strong> case studies, to <strong>the</strong> Embarcadero Freewayin San Francisco; Bonaventure <strong>Expressway</strong> inMontreal; Alaskan Way Viaduct in Seattle; andF.D.R. Drive in New York City.The 12 case studies in this report wereanalyzed from <strong>the</strong> combined perspectives <strong>of</strong>urban design, open space and public realm,transportation, and economic development.Applying <strong>the</strong>se four lenses revealed overalllessons that may resonate for <strong>the</strong> current<strong>Gardiner</strong> study. These lessons follow.It is important to note that whereas about half<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> case studies are built, o<strong>the</strong>rs are still inplanning and design stages. In this way, <strong>the</strong>cases <strong>of</strong>fer both lessons from implementationand inspiration for design ideas.Solutions come in different shapesand sizes.The case studies reflect a diversity <strong>of</strong>approaches – which suggests <strong>the</strong>re is nosingle strategy for addressing elevated highwayissues. Design and development strategiesundertaken by cities depend on physicalcontext, transportation needs, public realmgoals, and available resources, among o<strong>the</strong>rfactors.New York City, for example, had over US $1billion in federal funds available to createa 8.3 km (5 mile) urban boulevard. Theboulevard is abundantly landscaped andincludes a bicycle greenway. In contrast, <strong>the</strong>Amsterdam suburb Zaanstadt took a moremodest approach. It choose to live with anelevated highway by improving <strong>the</strong> spaceunderneath with a grocery and recreationprograms. The project cost €2.7 million.Though <strong>the</strong>se solutions have different scalesand costs, both became equally significantpublic ga<strong>the</strong>ring spaces for <strong>the</strong>ir respectivecity.Transportation solutions should beseen through <strong>the</strong> lens <strong>of</strong> city-buildingand quality <strong>of</strong> life.Elevated highway removal decisions areconventionally measured against transportationcriteria – level <strong>of</strong> service, travel time, etc.However, ambitious cities like San Franciscoand Montreal have viewed <strong>the</strong>ir highwaysfrom a different perspective. They have setgoals for waterfront access, public realm,transportation, sustainability, and development,<strong>the</strong>n accessed how <strong>the</strong>ir highways will have tochange to achieve <strong>the</strong>se greater urban goals.Transportation uses are continuallyevolving – changes in demographics,economics, and lifestyle effect trafficdemand.The highways <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mid-20th century,particularly in <strong>the</strong> United States, weredesigned with specific goals in mind. One keyplanning agenda was to connect downtownsto suburbs. Planners also sought to linkindustrial waterfronts to <strong>the</strong> new interstatehighway system.In some cases studied, city agencies foundthat <strong>the</strong>se historic goals no longer apply.Moreover, while <strong>the</strong>re is always concern abouturban highway congestion, sometimes trafficdemand actually decreases over time.In Chattanooga, for example, RiverfrontParkway no longer served as a though-routefor industrial trucking in <strong>the</strong> Tennessee River16<strong>Future</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gardiner</strong> <strong>Expressway</strong>

Valley as it did in <strong>the</strong> 1960s. In fact, <strong>the</strong>parkway had excess capacity. Redesigning<strong>the</strong> road as an at-grade boulevard did not<strong>the</strong>refore produce congestion downtown.Traffic demand can be managed.The most successful highway reconfigurationprojects complement changes to expresswayfunctions with new transit infrastructureand policy. Traffic demand strategies rangefrom increased public transit to user fees forparking, from incentives for alternatives tocommuting by car to congestion pricing.Seoul, for example, complemented <strong>the</strong>demolition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Cheonnggyecheon<strong>Expressway</strong> – which carried 120,000 vehiclesper day – with new bus rapid transit. Seattlewill add new light rail when <strong>the</strong> Alaskan WayViaduct is replaced with a tunnel. Theseimprovements not only encourage mode shift(from car to public transit, for example), butset <strong>the</strong> stage for reducing carbon emissions.Transportation infrastructure <strong>of</strong>fersextraordinary opportunities for design,creativity, and new public realm.Highway reconfiguration provides rareopportunities for cities to streng<strong>the</strong>nwaterfront connections and create new publicrealm <strong>the</strong>re. At <strong>the</strong> same time, some citieshave learned that <strong>the</strong>y need not always turn<strong>the</strong>ir back to infrastructure.New York City is developing a new publicesplanade under <strong>the</strong> elevated F.D.R. Drive inLower Manhattan. Through lighting, programdiversity, surface materials, and noiseattenuatingcladding, <strong>the</strong> space under <strong>the</strong>highway will be transformed into an inviting,active space. Moreover, innovative designwill give <strong>the</strong> East River Esplanade a uniquecharacter, making it a one-<strong>of</strong>-a-kind publicspace in <strong>the</strong> city.Infrastructure does not have to besingle-purpose or boring.Cities are transforming both de-commissionedand active infrastructure into new civiclandmarks and unexpected spaces for urbanactivity. Paris closes <strong>the</strong> Georges Pompidou<strong>Expressway</strong> in summer to create an urbanbeach along <strong>the</strong> banks <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Seine. BothParis and New York have re-imagined elevatedrailroads as linear parks. The design <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>High Line in New York integrates landscapewith an iconic industrial-era elevated structure.The public sector must be strategicin order to capture value <strong>of</strong> investmentsin infrastructure to serve bothcommunity and development goals.Public investment in highway reconfigurationand removal creates benefits – fromdevelopment parcels to increased propertyvalues to improved quality <strong>of</strong> life. The publicsector must act strategically in order tocapture this value. In Montreal, for example,parcels created by removing <strong>the</strong> Bonaventure<strong>Expressway</strong> will be sold to <strong>the</strong> privatesector for mixed-use development. Highwayremoval will also enhance <strong>the</strong> value <strong>of</strong> recentredevelopment in <strong>the</strong> neighboring CiteMultimedia.Conversely, opportunity costs accumulatewhen decision-making processes drag on.In Seattle, real estate speculators acquiredproperties along <strong>the</strong> Alaskan Way Viaductduring a decade <strong>of</strong> transportation studies. Thepublic sector lost <strong>the</strong> opportunity to acquire<strong>the</strong>se properties itself, <strong>the</strong>n increase revenuethrough disposition.City-building projects <strong>of</strong> this magnituderequire vision and active commitmentat <strong>the</strong> highest levels <strong>of</strong> leadership– mayors, governors, and citycouncils. Moreover, <strong>the</strong> full range <strong>of</strong>stakeholder input, from support toopposition, must be understood andresponded to substantively.City leaders need to support and advocate forintegrated approaches to infrastructure design.Their vision must embrace <strong>the</strong> full range <strong>of</strong>urban design, public realm, transportation,and economic development opportunities.Visionary leadership is complemented by aninformed and engaged public that has anactive role in developing design solutions.The <strong>Gardiner</strong> <strong>Expressway</strong> and downtown Toronto viewed from <strong>the</strong> south-east.SECTION IV: COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS 17

(This page intentionally left blank.)

Case StudiesSECTION V: Case studies 19

Case StudiesReplaceAlaskan Way Viaduct, Seattle, WABackgroundThe Alaskan Way Viaduct is a 3.2 kilometer(2 mile) four-lane double-stacked elevatedhighway (two one-way lanes on each level)along Elliot Bay in downtown Seattle.Constructed in 1959, <strong>the</strong> viaduct approachesdowntown Seattle from <strong>the</strong> south. It createsa physical barrier between Seattle’s baseballand football stadiums and its port area. Theviaduct mostly serves local traffic, whichby-passes downtown on <strong>the</strong> way from Seattle’snorth and south neighborhoods. The viaductalso limits access to <strong>the</strong> Elliot Bay waterfrontfrom downtown.An earthquake in 2001 damaged <strong>the</strong>structure’s joints and columns. Following<strong>the</strong> earthquake, <strong>the</strong> viaduct also settled,raising alarm that Seattle’s seawall sustaineddamage as well. It was determined after <strong>the</strong>earthquake that removing or replacing <strong>the</strong>viaduct would be more cost effective than aretr<strong>of</strong>it.Because <strong>the</strong> Washington State Department <strong>of</strong>Transportation (WSDOT) owns <strong>the</strong> viaduct and<strong>the</strong> City <strong>of</strong> Seattle owns <strong>the</strong> seawall, removaland replacement studies were jointly initiated.A range <strong>of</strong> alternatives – from an urbanboulevard to a cut-and-cover tunnel similar toportions <strong>of</strong> Boston’s Big Dig – were analyzed.Parking is a common use under <strong>the</strong> Viaduct.The Alaskan Way Viaduct separates downtown Seattlefrom <strong>the</strong> waterfront.Alaskan Way Viaduct Section – Before (Existing)20<strong>Future</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gardiner</strong> <strong>Expressway</strong>

The Governor announced in early 2009that <strong>the</strong> viaduct will be replaced by deepbored tunnel under downtown Seattle. Thisalternative was not evaluated in <strong>the</strong> EIS. Costfor <strong>the</strong> bored tunnel is estimated at US $4.24billion.Urban DesignThe Alaskan Way Viaduct, in particularbecause it is a double-decker structure,is thought to reduce <strong>the</strong> quality <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>downtown environment and potential portareadevelopment value. Its visual impact onSteinbreuk Park is especially felt, since thisopen space is symbolically important to bothdowntown and <strong>the</strong> city.Most land in <strong>the</strong> downtown waterfront areais privately-owned. While some developmentparcels will be created, <strong>the</strong> City <strong>of</strong> Seattledoes not stand to significantly re-capturepublic investment value through landdisposition. Direct economic benefits to <strong>the</strong>City would come through increased tourismand rising property values.The viaduct also poses a sharp environmentalchallenge to Seattle – maintaining currenttraffic volumes on <strong>the</strong> viaduct will likelyexceed state carbon reduction goals, some <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> most ambitious in <strong>the</strong> U.S.The study’s urban design objectives weremostly related to existing waterfront land useplans. Pedestrian and bicycle access werekey goals, as well enhanced waterfront andmountain views. All alternatives studied howto create waterfront pedestrian realm andwhe<strong>the</strong>r bringing <strong>the</strong> viaduct to grade might,in fact, diminish existing pedestrian realm.The viaduct is an aging infrastructure. For thisreason, safety and design deficiencies – forexample, 3-meter-wide (10 feet) lanes – werekey concerns. Yet transportation strategiesrevolved around a key question. Shouldviaduct redesign accommodate existing trafficvolumes – 110,000 vehicles per day – orencourage mode shift?Existing condition under <strong>the</strong> Viaduct.Rendering <strong>of</strong> proposed condition.Alaskan Way Viaduct Section – After (Proposed)SECTION V: Case studies 21

Case StudiesAll alternatives were designed for multiplemodes, including light rail. However,alternatives posed markedly differentreplacement approaches. On <strong>the</strong> onehand, investment could be made in a largeinfrastructure solution. On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r, manysmaller street reconfigurations and transitprojects might fulfill <strong>the</strong> City’s needs.ProcessSix alternatives were studied: no build;“rebuild” – rebuild a section <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> elevatedstructure and replace <strong>the</strong> rest with an urbanboulevard; “aerial” – rebuild <strong>the</strong> entireelevated structure; “tunnel” – two alternativeswith varying capacity; and “surface” – a newurban boulevard.These were combined and narrowed to twoalternatives: a tunnel with a four-lane at-gradeboulevard and an elevated structure with a sixlaneat-grade boulevard.Public dialogue about <strong>the</strong> Alaskan Way Viaductfocused primarily on congestion. In a 2008ballot initiative, <strong>the</strong> public rejected bothalternatives. Media suggested voters wereinfluenced by <strong>the</strong> specter <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Big Dig.Ultimately, decision-making authority lay with<strong>the</strong> state. The deep bored tunnel is <strong>the</strong> mostexpensive alternative and has limited lanewidth and access ramps. However, it will allowfor minimal disruption during construction(as compared to cut-and-cover technology).The state will assume US $2.81 billion <strong>of</strong>expenses for <strong>the</strong> tunnel. The city and port willpay for seawall reconstruction. The project isestimated to create 10,000 jobs over 10 years.Throughout <strong>the</strong> eight-year process, <strong>the</strong> city lostopportunities to capture incremental value <strong>the</strong>project would potentially create. Real estatespeculators began purchasing land within <strong>the</strong>viaduct corridor that might have come undercity-ownership.LESSONS <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> alaskan way viaduct• Choice <strong>of</strong> technology played a key role in political decisionmaking.Yet while <strong>the</strong> deep bored tunnel and urban boulevard willenable significant urban design improvements, it requires massiveresource allocation and trade-<strong>of</strong>fs – over US $4 billion.• Choice <strong>of</strong> technology also posed transportation trade-<strong>of</strong>fs. Lanewidths are constrained and <strong>the</strong>re are limited ramp connections.• All alternatives considered design implications for integratingmultiple transportation modes, including light rail, pedestrian, andbicycle.• Development and value capture opportunities were lost to <strong>the</strong> Citythroughout <strong>the</strong> prolonged study process.22<strong>Future</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gardiner</strong> <strong>Expressway</strong>

West Side Highway, New York, NYReplace / RemoveBackgroundThe West Side Highway extends for 8.2kilometers (5 miles) from 58th Street toBattery Park along Manhattan’s Hudson Riverwaterfront.Construction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> West Side Highwaywas completed in 1937. The new elevatedhighway with an at-grade street below servicedriver piers and adjacent manufacturing anddistribution districts. A section <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> highwaycollapsed in 1974, closing it to traffic andopening a twenty-year debate on <strong>the</strong> WestSide’s future.The Mayor, Governor, and o<strong>the</strong>r cityleaders shortly-<strong>the</strong>reafter advocated for <strong>the</strong>Westway. This massive project, designed byVenturi Scott Brown, proposed 220 acres<strong>of</strong> redevelopment, all funded with federaland state transportation grants. A tunnelunder 178 acres <strong>of</strong> landfill would replace<strong>the</strong> highway. Open space and new housingwould be constructed on <strong>the</strong> fill. Legal battles,however, stalled <strong>the</strong> project until 1985,when <strong>the</strong> City diverted <strong>the</strong> funds to o<strong>the</strong>rtransportation projects.US $690 million remained for <strong>the</strong> West SideHighway’s reconstruction. In 1987, <strong>the</strong> Citydeveloped a new plan for an at-grade six-laneboulevard (three lanes in each direction),which was completed in 2001.Urban DesignThe Westway and final West Side HighwayReconstruction Project reflect two different,era-specific planning approaches. Whereas<strong>the</strong> Westway is more aligned with largescaleurban renewal, <strong>the</strong> eventual West SideHighway reconstruction illustrates a moreView <strong>of</strong> West Side Highway facing north; circa 1940s. Hudson River waterfront shipping and industrial uses are seen on <strong>the</strong> left.SECTION V: Case studies 23

contextual approach. Even so, <strong>the</strong> Westwaywas conceptualized as a more contextsensitivedesign than 1960s-era highwayprojects that displaced neighborhoods.By <strong>the</strong> time <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> collapse, <strong>the</strong> West SideHighway’s role had changed. The industrialHudson waterfront was in decline as anactive city economy sector. The highway’snarrow lanes and sharp turns also made <strong>the</strong>structure technologically obsolete. Following<strong>the</strong> highway closure, <strong>the</strong> West Side was largelyperceived to be a haven for crime.The Westway would have created long-termreal estate opportunities for <strong>the</strong> City forland disposition. However, <strong>the</strong> cost – US$1.7 billion – was generally perceived to beexcessive for a new highway. The West SideHighway Reconstruction project created newdemand for adaptive reuse and infill along <strong>the</strong>West Side. Former industrial buildings havebeen converted to residential, for example.Area property values increased by 20 percent,View <strong>of</strong> West Side Highway facing south after completion <strong>of</strong> restoration project in 2000s.West Side Highway Section – Before (1930s to 1970s)24<strong>Future</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gardiner</strong> <strong>Expressway</strong>

totalling US $200 million <strong>of</strong> added value.The boulevard proposal EIS questionedwhe<strong>the</strong>r Manhattan even needed a limitedaccessarterial. The transportation studyanalyzed nearly all <strong>of</strong> Manhattan andconcluded that <strong>the</strong> West Side Highway actedmore as a collector-distributor road. Replacing<strong>the</strong> highway with an at-grade boulevard,<strong>the</strong>refore, wouldn’t be a loss for most drivers.(Whereas <strong>the</strong> West Side Highway carried140,000 vehicles per day in <strong>the</strong> 1970s, todayit carries 95,000).The Department <strong>of</strong> City Planning authored<strong>the</strong> new boulevard plan. Design objectivesincluded creating a new multi-modal routeand pedestrian waterfront connections as wellas streetscape improvements. To this firstend, <strong>the</strong> design incorporates a segment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>Manhattan Greenway bicycle and pedestrianpath. The plan also limits auto access andturning locations, and provides a raisedmedian in order to increase pedestrian safety.Landscape plays a significant role <strong>the</strong>boulevard’s overall visual quality. Barrier curbsand <strong>the</strong> median are designed to be 0.6- to0.85-meters-tall. These high curbs <strong>of</strong>fer deepplanting beds, allowing for a variety <strong>of</strong> trees,shrubs, and flowers. The diverse plantingpalette gives <strong>the</strong> West Side Highway a parkwaycharacter.The West Side Highway is also integrated, interms <strong>of</strong> design, with surrounding planninginitiatives. Pedestrian crossing locations,for example, are coordinated with plannedentrances to Hudson River Park. Surfacematerials, paving, and exterior furnishingswere also aligned with design standardsfor Hudson River Park and <strong>the</strong> ManhattanGreenway.ProcessThe Westway was ultimately stalled in courton environmental grounds. The court uphelda lawsuit contending that <strong>the</strong> project EIS didnot properly consider impacts on striped bass.These migratory fish make habitat in <strong>the</strong> piles<strong>of</strong> abandoned piers along <strong>the</strong> Hudson.The scale and ambition <strong>of</strong> both <strong>the</strong> Westwayand West Side Highway Reconstruction Projectwere surely enabled by <strong>the</strong> funding source.Because most funds were federal, <strong>the</strong> projectswere more politically palatable to local leadersand residents.The Manhattan Waterfront Greenway parallels<strong>the</strong> West Side Highway.LESSONS <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> west side highway / westway• The West Side Highway Reconstruction Project did not leverageas much development as is likely to occur in Toronto. Instead, itprovided amenity access that encouraged substantial economicgrowth in upland neighborhoods.• The details <strong>of</strong> roadbed design provided <strong>the</strong> opportunity for a richerlandscape. The West Side Highway’s parkway character makes<strong>the</strong> boulevard an appealing urban amenity and refers to <strong>the</strong> City’slegacy <strong>of</strong> constructing parkways.West Side Highway Section – After (Existing)SECTION V: Case studies 25

Case StudiesRemoveBonaventure <strong>Expressway</strong>, Montreal, QCBackgroundThe Bonaventure <strong>Expressway</strong> is a 1-kilometer(0.6 miles) elevated highway extendingeastward from downtown Montreal to <strong>the</strong>Lachine Canal.Constructed in <strong>the</strong> 1967, <strong>the</strong> six-laneBonaventure <strong>Expressway</strong> parallels <strong>the</strong>CN Railroad viaduct, which terminates atBonaventure Place and Central Stationdowntown. The expressway opened shortlybefore Expo ‘67, a large-scale “world’s fair”event. Two three-lane one-way at-grade streets– Rue Duke and Rue Nazareth – are located onei<strong>the</strong>r side <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> elevated structure.The viaduct and highway separate twoneighborhoods. To <strong>the</strong> south, Griffintown ischaracterized by nineteenth-century industrialbuildings. To <strong>the</strong> north, <strong>the</strong> Cite Multimedia isa new mixed-use redevelopment area .The Societe du Havre de Montreal (SHM), aquasi-governmental organization establishedin 2002, proposed demolition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>Bonaventure in 2005. As part <strong>of</strong> Montreal’soverall waterfront development strategy, RuesDuke and Nazareth would be expanded. Landreclaimed from <strong>the</strong> Bonaventure would beredeveloped as <strong>of</strong>fice, residential, and hotel.The development plan also includes improvedarea public transit and new waterfront openspace.The Bonaventure <strong>Expressway</strong> enters downtownMontreal from <strong>the</strong> east; Peel Basin andLachine Canal are in <strong>the</strong> foreground.Parking is a current use under <strong>the</strong>Bonaventure <strong>Expressway</strong>.Bonaventure <strong>Expressway</strong> Section – Before (Existing)26<strong>Future</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gardiner</strong> <strong>Expressway</strong>

The City is currently reviewing <strong>the</strong> projectand approval may come in spring 2009. Theproject cost is estimated at CA $90 million.Urban DesignFrom <strong>the</strong> perspective <strong>of</strong> SHM, removing<strong>the</strong> Bonaventure <strong>Expressway</strong> posed keydevelopment opportunities – creating 4.25acres <strong>of</strong> new development parcels andincreasing <strong>the</strong> value <strong>of</strong> Cite Multimediaredevelopment efforts. The Bonaventure hadplayed a role in <strong>the</strong> area’s decline during <strong>the</strong>1970s and 80s. In addition, <strong>the</strong> structureblocked views and diminished pedestrianaccess to Peel Basin, a potential waterfrontamenity.Urban design objectives integratetransportation, open space, and developmentplanning. The new district would, first <strong>of</strong>all, provide an entrance to <strong>the</strong> city and <strong>the</strong>recently redeveloped Cite Multimedia andQuartier International de Montreal. Though <strong>the</strong>plan proposes expanding Rues Duke andNarazeth from three to four lanes, improvedpublic transit is planned to reduce overalltraffic demand. Light rail is proposed to serveas a link within Montreal’s waterfront tramsystem.O<strong>the</strong>r key objectives are pedestrian andbicycle realm improvements. In particular,<strong>the</strong> plan includes an underground pedestriannetwork connecting Montreal Metro stationswith new <strong>of</strong>fice and residential destinations.Rendering <strong>of</strong> proposed condition.Rendering <strong>of</strong> proposed condition.Removal <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Bonaventure <strong>Expressway</strong> willcreate parcels for new development.Bonaventure <strong>Expressway</strong> Section – After (Proposed)SECTION V: Case studies 27

Montreal already has an extensive network<strong>of</strong> tunnels – known as La Ville Souterraine –which link transit stations and undergroundretail centers.The plan also incorporates <strong>the</strong> railroad viaductas a development site. Similar to <strong>the</strong> Viaductdes Arts in Paris, <strong>the</strong> plan proposes to carveretail spaces into <strong>the</strong> CN Railroad viaduct’svolume.The project is estimated to encourage$2.7 billion in private investment. Overall,employment created by <strong>the</strong> project would addmore than CA $2 billion to Quebec’s grossdomestic product. Jobs estimates range from25,700 to 41,400.ProcessSHM purposed an integrated designapproach with L’autoroute BonaventureVision 2025, specifically prioritizingsustainable development over mobility-basedplanning. The plan’s five key principlesemphasize quality <strong>of</strong> life, economic benefits,public transit, public realm, and an opendevelopment process. Accommodatingautomobile traffic was not <strong>the</strong> only projectdrivingpriority.lessons <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> bonaventure expressway• Ra<strong>the</strong>r than evaluating <strong>the</strong> highway removal project only in terms<strong>of</strong> transportation planning, <strong>the</strong> implementing agency set ambitiousgoals for urban design, public realm, and development, <strong>the</strong>n askedhow <strong>the</strong> highway would have to change to achieve <strong>the</strong> goals. SHMframed <strong>the</strong> project as <strong>the</strong> process <strong>of</strong> creating a new urban district.• Removal <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Bonaventure will reduce traffic capacity at <strong>the</strong>same time that new development will increase demand. The planproposes a combination <strong>of</strong> increased public transit capacity, rushhourdemand management, and optimization <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> local roadnetwork to reduce automobile traffic. These strategies are alignedwith Montreal’s transportation plan and <strong>the</strong> Kyoto Protocols.Rendering <strong>of</strong> proposed condition looking south on Rue Nazareth. New development is to <strong>the</strong> left; new retail in <strong>the</strong> ground-level <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> rail roadembankment is to <strong>the</strong> right.28<strong>Future</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gardiner</strong> <strong>Expressway</strong>

Riverfront Parkway, Chattanooga, TNRemoveBackgroundThe City <strong>of</strong> Chattanooga has since 2000increasing turned its attention to orientingrecent downtown investments toward <strong>the</strong>Tennessee River. Doing so required replacingRiverfront Parkway with an urban boulevardand, subsequently, creating new waterfrontopen space.Riverfront Parkway followed <strong>the</strong> TennesseeRiver’s contour for 2.7 kilometers (1.7 mile)as it curved around downtown Chattanooga’snor<strong>the</strong>rn edge. The four-lane parkway wasconstructed in <strong>the</strong> 1960s in order to speedregional industrial truck traffic throughChattanooga. It separated <strong>the</strong> medium densitydowntown from <strong>the</strong> river. Its median-dividersprevented pedestrians from crossing <strong>the</strong> roadto access <strong>the</strong> waterfront.The City constructed and renovated severalcultural amenities on both sides <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>parkway during <strong>the</strong> 1980s and 90s. Theseincluded <strong>the</strong> Tennessee Aquarium, a baseballstadium, and a museum <strong>of</strong> American art.Following <strong>the</strong>se investments, <strong>the</strong> City soughtto reconnect downtown to <strong>the</strong> river andinitiated efforts to remove Riverfront Parkway.A quasi-governmental organization, RiverCityCompany, hired Hargreaves Associatesin 2004 to develop <strong>the</strong> “21st CenturyRiverfront Parkway was reconfigured as an at-grade urban boulevard during <strong>the</strong> 2000s.SECTION V: Case studies 29

Case StudiesWaterfront”. The plan creates connectionsacross <strong>the</strong> new boulevard to 129 acres <strong>of</strong> newopen spaces and mixed-use districts along <strong>the</strong>Tennessee River.The 21st Century Waterfront cost US $120million to construct (which excludes cost <strong>of</strong>removing Riverfront Parkway).Urban DesignThe parkway project and 21st CenturyWaterfront were implemented in parallel.Chattanooga’s downtown grid was integratedwith <strong>the</strong> boulevard, <strong>the</strong>reby creating waterfrontpedestrian connections and new developmentparcels. The new waterfront amenitiesenhanced <strong>the</strong>ir value.By <strong>the</strong> 1990s, Riverfront Parkway no longerserved its initial use. In fact, <strong>the</strong> parkwayhad excess capacity. Its redesign was not anissue <strong>of</strong> accommodating traffic, but ra<strong>the</strong>rcalibrating its dimensions for current volumes.Lanes were reduced to two, except fordowntown, where it has four. Two additionaldowntown intersections were added to dispersepotential congestion.The 21st Century Waterfront is composed<strong>of</strong> six open space and development districtson both sides <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> river. Because <strong>the</strong>re islittle developable land between <strong>the</strong> parkwayand river, most planned development hasoccurred just upland <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> new roadway. Thedowntown side includes a reconstructed parkwith terraced public spaces leading to <strong>the</strong> riveredge and amphi<strong>the</strong>ater <strong>the</strong>re. Piers provideboat launches and river views.Hargreaves’ plan is characterized by stronglandforms and active shapes. These provideboth flood control as well as recreation space.The Riverfront Parkway streetscape today connects downtown to <strong>the</strong> Tennessee River.30<strong>Future</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gardiner</strong> <strong>Expressway</strong>

A sweeping fly-over bridge connects a newdowntown public plaza to <strong>the</strong> arts district,located on a dramatic river bluff. The design<strong>the</strong>refore gives downtown and <strong>the</strong> riverfront acontemporary character.ProcessRiverCity Company was established in <strong>the</strong>1980s to steward redevelopment alongChattanooga’s waterfront. The organizationfinanced <strong>the</strong> 21st Century Waterfront usingno Chattanooga general funds. Fifty percent<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> development budget came from a hoteltax, <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r fifty from private sources.The vision for <strong>the</strong> waterfront was alsoestablished by political and agency leadership.Both <strong>the</strong> Mayor and <strong>the</strong> city’s Planningand Design Studio strongly advocated foran innovative approach for downtown and<strong>the</strong> river. Whe<strong>the</strong>r such vision will continuewas questioned in 2005. The mayoralelection in that year was won by a candidatewho specifically ran on an anti-downtowninvestment platform.The City <strong>of</strong> Chattanooga reports that itleveraged <strong>the</strong> US $120 million investment in<strong>the</strong> waterfront for US $2 billion in new publicand private development. Before <strong>the</strong> parkwayremoval was complete, more than US $100million in new mixed-use and residentialdevelopment downtown had already beenconstructed or planned.The 21st Century Waterfront <strong>of</strong>fers publicaccess to <strong>the</strong> river.lessons <strong>of</strong> riverfront parkway / 21st century waterfront• This project illustrates that to implement an innovative designvision, it must be supported and sought after by <strong>the</strong> highest levels<strong>of</strong> leadership.• The City recognized that <strong>the</strong> role <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> highway had shifted –from serving as a through-route for industrial trucking to providingaccess to cultural and natural amenities.• The roadway design is calibrated for current traffic volumes.Pedestrian connections across <strong>the</strong> River over views <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> new watefront park.SECTION V: Case studies 31

Case StudiesRemoveEmbarcadero Freeway, San Francisco, CABackgroundThe Embarcadero Freeway was a 2.5 kilometer(1.6 mile) double-deck highway constructed in1957 in order to provide a connection between<strong>the</strong> Bay Bridge and Golden Gate Bridge.The freeway wound through medium densityresidential neighborhoods, includingChinatown, Rincon Hill, and Transbay, as wellas San Francisco’s central business district.Public protest in <strong>the</strong> 1950s – <strong>the</strong> “freewayrevolt” – led to a reduction in scale <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>new highway. Even so, <strong>the</strong> Embarcadero was avisual and physical barrier between downtownand <strong>the</strong> bay.Following damage sustained during <strong>the</strong> 1989Loma Prieta earthquake, CALTRANS studiedreplacement strategies for <strong>the</strong> Embarcadero.Two years later, <strong>the</strong> Embarcadero wasdemolished and replaced with a six-laneWhen constructed in <strong>the</strong> 1950s, <strong>the</strong> Embarcadero separated downtown from <strong>the</strong>Ferry Building and Bay.Embarcadero Freeway Section – Before (1950s to 1980s)32<strong>Future</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gardiner</strong> <strong>Expressway</strong>

at-grade boulevard. The new boulevardwas developed along with a new waterfrontpromenade, pedestrian- and bicycle-ways, anda streetcar line.Fifty percent less cars use <strong>the</strong> boulevarddaily than <strong>the</strong> elevated structure, whichcarried 80,000 vehicles per day. There wasno significant increase in downtown trafficcongestion.Urban DesignThe 1989 earthquake and subsequent collapserevived in public imagination <strong>the</strong> potential for<strong>the</strong> San Francisco to reestablish its historicrelationship to <strong>the</strong> bay. The Embarcadero wasperceived to be an urban eyesore and barrierto waterfront access. In addition, it marred <strong>the</strong>city’s front door, separating <strong>the</strong> iconic FerryBuilding from <strong>the</strong> foot <strong>of</strong> Market Street.Urban boulevard and esplanade constructionwas guided by clear urban design principles,<strong>the</strong>reby creating new developmentopportunities. Design guidelines and a publicart program shaped <strong>the</strong> boulevard’s consistentand unique character. Pedestrian-amenabledesign made <strong>the</strong> boulevard a generous publicga<strong>the</strong>ring space.Subsequently, 100 acres <strong>of</strong> land werereclaimed for new development. The FerryBuilding was reopened to <strong>the</strong> public as aregional food market. Two o<strong>the</strong>r waterfrontprojects – Pier 1 and <strong>the</strong> Embarcadero Center– attracted new retail and <strong>of</strong>fice development.Housing development also significantlyincreased. Over 7,000 new housing units wereplanned for former rights-<strong>of</strong>-way and rampsin Rincon Hill and Transbay. 2,000 unitswere developed in <strong>the</strong> south <strong>of</strong> Market area.Today, over 83 percent <strong>of</strong> residents in south <strong>of</strong>Market arrived after 1990.The redesign envisioned EmbarcaderoBoulevard as a multi-modal street integratedwith <strong>the</strong> surrounding urban grid. TransitView <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Ferry Building from <strong>the</strong> south-east.Removing <strong>the</strong> Embarcadero reclaimed over one mile <strong>of</strong> waterfront.Embarcadero Freeway Section – After (Existing)SECTION V: Case studies 33

improvements in <strong>the</strong> Embarcadero corridor,however, built upon existing efforts. SanFrancisco had implemented “transit first”policies since 1972. The city Board hadpassed highway demolition resolutions threetimes in <strong>the</strong> 1970s and 80s. In 1986, <strong>the</strong>issue was brought to public referendum, whichwas voted down.Concern over congestion increases downtowndid not materialize despite an immediate25 percent capacity reduction. Forty-twopercent <strong>of</strong> drivers found alternate routes withinsix weeks <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> earthquake. O<strong>the</strong>r driversreduced discretionary trips or opted for publictransit.ProcessCALTRANS studied three alternatives for <strong>the</strong>damaged Embarcadero Freeway: seismologicalretr<strong>of</strong>it; a tunnel; and an at-grade urbanboulevard.The third alternative was selected primarilybased on cost. This alternative attractedsignificant public support, in particular fromanti-growth advocates. Almost immediatelyafter <strong>the</strong> earthquake, San Francisco’s Mayorannounced his support for demolishing <strong>the</strong>Embarcadero.Yet <strong>the</strong>re was also opposition. Chinatownmerchants argued removing <strong>the</strong> highway woulddecrease <strong>the</strong>ir customer base, which wasincreasingly shopping in suburban locations.lessons <strong>of</strong> embarcadero freeway• The Embarcadero Freeway removal signaled a shift in prioritiesamong municipal <strong>of</strong>ficials from mobility-based planning tosustainable urban development.• Values <strong>of</strong> property adjacent to <strong>the</strong> new Embarcadero Boulevardincreased by 300 percent; jobs in <strong>the</strong> area increased by 23percent.• Urban design has a key role to play in highway removal –boulevard design slowed traffic, <strong>the</strong>reby creating an environmentamenable to retail and residential development. In addition, landuse planning was intergrated with traffic engineering.The Ferry Building has becoming a ga<strong>the</strong>ring space for <strong>the</strong> city. Over 25,000 people visitit each weekend.34<strong>Future</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gardiner</strong> <strong>Expressway</strong>

Cheonggyecheon <strong>Expressway</strong>, Seoul, KoreaRemoveBackgroundThe Cheonggyecheon Restoration Projecttransformed a 6.1-kilometer (3.75 miles)elevated expressway corridor in downtownSeoul into a linear park and reclaimed stream.Between 1958 and 1976, <strong>the</strong>Cheonggyecheon stream was incrementallycovered by a ten-lane at-grade street. A fourlaneelevated highway was constructed above.The Cheonggye district, composed <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong>ficebuildings and retail markets, became amongSeoul’s most congested areas.business district eastward, day-light <strong>the</strong>buried stream, and create an open spaceamenity for <strong>the</strong> city. Highway removal wouldbe complemented by new bus rapid transit.In just 27 months, <strong>the</strong> highway had beenreplaced by pedestrian esplanades andgardens. Two-lane boulevards were locatedat-grade on ei<strong>the</strong>r side <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> open space,which, along with <strong>the</strong> stream, is two meters(6.5 feet) below-grade.The project cost was publicly reported as US$390 million, though <strong>the</strong> budget may havebeen as much as US $900 million.A new mayor initiated a plan in 2002 todemolish <strong>the</strong> highway from <strong>the</strong> centralThe Cheonggyecheon <strong>Expressway</strong> contributed to declining property values and populationloss in Seoul’s downtown before it was replaced by a linear park.SECTION V: Case studies 35

A esplanade <strong>of</strong>fers public access to <strong>the</strong> daylightedcreek.Urban DesignThe Cheonggyecheon Restoration Projectsignaled a shift in municipal <strong>of</strong>ficials’priorities towards quality <strong>of</strong> life issues.Moreover, <strong>the</strong> new Mayor committed toremaking Seoul as a sustainable city. Not onlydid <strong>the</strong> Cheonggye area suffer from congestion,but also population and property valuedecline. The new open space would benefit<strong>the</strong> 200,000 area merchants as well as Seoulresidents as a whole.Pedestrian access to <strong>the</strong> below-grade publicspace is provided at 5-minute-walk intervalsby terraced steps. New pedestrian bridgesconnect ei<strong>the</strong>r side <strong>of</strong> Cheonggyecheon. Avariety <strong>of</strong> landscape types and water featurescharacterize different park segments. In <strong>the</strong>year following its opening, <strong>the</strong> park attracted90,000 visitors daily. Thirty percent <strong>of</strong> visitorscame from outside Seoul’s metropolitan area.The elevated structure removal occurred at<strong>the</strong> same time as significant upgrades toSeoul’s public transportation system. A busrapid transit route was introduced to absorbriders from at least 120,000 cars formerlyon <strong>the</strong> expressway. Bus rapid transit was alsoincreased on feeder routes. In <strong>the</strong> previousdecade, <strong>the</strong> City created incentive programs toencourage commuters to use transit and raiseduser fees for parking downtown.Combined, <strong>the</strong>se transportation strategiesresulted in a nine percent decrease in trafficinto <strong>the</strong> central business district.Cheonggyecheon Highway Section – Before (1950s to 2000s)36<strong>Future</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gardiner</strong> <strong>Expressway</strong>

Sustainability objectives guided <strong>the</strong> project aswell. The City recycled ninety-six percent <strong>of</strong>demolition debris for street paving material.Removal <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> expressway appears to havelowered summer temperatures in <strong>the</strong> projectarea by seven degrees.The seasonal Cheonggyecheon stream, however,is not truly restored. Water is diverted from <strong>the</strong>nearby Han River to assure continuous waterflow in <strong>the</strong> 1-meter-deep (3 feet) streambed.ProcessMuch impetus behind <strong>the</strong> project was political.The Mayor had campaigned on quality <strong>of</strong> lifeissues, including <strong>the</strong> proposal to demolish <strong>the</strong>Cheonggyecheon <strong>Expressway</strong>. Having madegood on his promise, he campaigned for andwon <strong>the</strong> Korean presidency.Values <strong>of</strong> property adjacent to <strong>the</strong>Cheonggyecheon project are estimated tohave increased by 30 percent. Between US$8.5 and $25 billion <strong>of</strong> long-term economicbenefits are estimated as a result <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>project.lessons <strong>of</strong> cheonggyecheon restoration project• Highway removal was coordinated with system-wide transportationstrategies. New bus rapid transit, a form <strong>of</strong> congestion pricing, andparking user fees toge<strong>the</strong>r helped to reduce traffic downtown after<strong>the</strong> Cheonggyecheon <strong>Expressway</strong> was demolished.• The Cheonggyecheon Restoration Project illustrates how <strong>the</strong> desireto remake <strong>the</strong> city’s image can drive large-scale infrastructureimprovements.• Implementation occurred in an incredibly short timeframe. Yet<strong>the</strong> project followed a top-down, urban renewal planning model– thousands <strong>of</strong> street merchants, for example, were relocated out<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> district. This planning approach is less feasible in NorthAmerica.Cheonggyecheon Highway Section – After (Existing)SECTION V: Case studies 37

Case StudiesRemoveSheridan <strong>Expressway</strong>, Bronx, NYBackgroundThe Sheridan <strong>Expressway</strong> is a 2 kilometer(1.25 mile) highway along <strong>the</strong> Bronx Riverin <strong>the</strong> Bronx. It connects <strong>the</strong> Bruckner<strong>Expressway</strong> to <strong>the</strong> Cross Bronx <strong>Expressway</strong>.The Sheridan was constructed in <strong>the</strong> 1960sas a minor link in <strong>the</strong> Bronx highway system.The Bronx has historically shared <strong>the</strong> heaviestproportion <strong>of</strong> New York City’s trucking traffic.The Sheridan separates a high densityresidential neighborhood <strong>of</strong> five- to six-storyapartment buildings from <strong>the</strong> Bronx River.Immediately to <strong>the</strong> south is Hunts PointMarket, <strong>the</strong> world’s largest wholesale fooddistribution center.The New York State Department <strong>of</strong>Transportation (NYSDOT) undertook studiesin <strong>the</strong> late-1990s to improve access toHunts Point. Fulton Fish Market had justrelocated from Lower Manhattan to HuntsPoint. At <strong>the</strong> same time, a coalition <strong>of</strong> nonpr<strong>of</strong>itorganizations – including South BronxWatershed Alliance and Sustainable SouthBronx – developed in 1999 a community plan.It proposed an at-grade boulevard to replace<strong>the</strong> Sheridan, reclaiming 28 acres for openspace and housing.Though NYSDOT incorporated <strong>the</strong> communityplan into its alternative plan, <strong>the</strong> agency’srecommendation in 2007 was to retain <strong>the</strong>Sheridan <strong>Expressway</strong>. Subsequently, NYSDOTannounced in 2008 that because <strong>the</strong> earlierrecommendation was determined to beinfeasible, <strong>the</strong> agency will continue to studytwo options – highway removal and retention –and will issue a new report in 2010.Urban DesignThe community plan argues <strong>the</strong> Sheridan<strong>Expressway</strong> has excess capacity. Replacing itwith an at-grade boulevard would <strong>the</strong>reforeremove a waterfront barrier without increasingcongestion or travel times. The Sheridan<strong>Expressway</strong> is also bound to historicenvironmental justice issues in <strong>the</strong> SouthBronx.Since <strong>the</strong> Bronx shares <strong>the</strong> largest volumeCyclists on Sheridan <strong>Expressway</strong> during bicycle event.38<strong>Future</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gardiner</strong> <strong>Expressway</strong>

<strong>of</strong> truck traffic, its neighborhoods have highincidences <strong>of</strong> asthma and o<strong>the</strong>r air-qualityrelatedhealth issues. Construction <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>highway in <strong>the</strong> early-1960s was followed bytwo decades <strong>of</strong> neighborhood disinvestment.NYSDOT focused its study on access to HuntsPoint Market. It did not consider urban designissues.The community plan aligned highwayremoval with neighborhood and open spaceplanning goals. The plan includes 1,200affordable housing units, 120,000 SF <strong>of</strong>retail, community, and manufacturing space,and a 10-acre park. The new waterfront openspace would provide a key link in <strong>the</strong> overallplan for <strong>the</strong> 37-kilometer (23 miles) BronxRiver watershed – which has gained two newopen spaces in <strong>the</strong> last five years. In addition,highway removal would reclaim land forhousing development.The Community plan estimates newdevelopment would create 700 new jobs.Similar waterfront park projects in NewYork City, such as Hudson River Park,have stimulated reinvestment in uplandneighborhoods.ProcessThree families <strong>of</strong> alternatives were considered:remove <strong>the</strong> Sheridan <strong>Expressway</strong> andreplace in an at-grade boulevard; reconstructexpressway ramps to improve Hunts Pointaccess; and reconstruct <strong>the</strong> ramps andprovide additional access from Port Morristo <strong>the</strong> south. Overall, 21 alternatives wereevaluated within <strong>the</strong> three families. NYSDOTrecommended two alternatives from family two.A multi-step process evaluated <strong>the</strong> alternativesagainst 14 objectives. First, through apublic process, <strong>the</strong> alternatives were scoredagainst <strong>the</strong> objectives. Second, quantitativemeasures were assigned to each objective and<strong>the</strong> alternatives were scored again. In bothinstances, <strong>the</strong> scores were weighted based onpublic input.NYSDOT’s ramp improvement alternativesoutscored <strong>the</strong> highway removal alternatives. Infact, because public input preferred reducingtruck traffic on local streets as well as truckemissions, <strong>the</strong> highway removal alternativesquantitatively scored poorly.lessons <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> sheridan expressway• The evaluation methodology was overly complicated. By focusingon transportation objectives, <strong>the</strong> evaluation obscured neighborhoodopen space and development goals.• The community plan reclaims land for development and increasesneighborhood value through new waterfront connections.The Bronx River Watershed Alliance proposes to create a 10-acre park and 1,200 housing units by removing <strong>the</strong> Sheridan <strong>Expressway</strong>.SECTION V: Case studies 39

Case StudiesAmeliorateA8ern8, Zaanstadt, The Ne<strong>the</strong>rlandsBackgroundThe City Council <strong>of</strong> this small suburb 16kilometers (10 miles) north <strong>of</strong> Amsterdamundertook in 2003 an initiative to createa new town square. The project sought toreactivate <strong>the</strong> space under A8, a 7-meter-tallelevated highway.A8 enters town from <strong>the</strong> east, just afterspanning <strong>the</strong> River Zaan. When constructed in<strong>the</strong> 1970s, A8 formed a harsh physical barrierbetween <strong>the</strong> town’s two civic activity centers,<strong>the</strong> church and town hall. Residents <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>low-slung apartment blocks and townhousesin <strong>the</strong> surrounding neighborhood lost <strong>the</strong>irriver views and access. The effort to redesignA8 was advocated for primarily by residentsand private businesses. At <strong>the</strong> time <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>Council’s initiative, A8’s underside was mostlyused for parking.NL Architects, <strong>the</strong> town’s design consultant,conceptualized <strong>the</strong> 40- by 400-meter areaas a long “civic arcade”. The introduction<strong>of</strong> new programs, cladding <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> elevatedstructure, and surface treatments transformedA8 from a barrier into a ga<strong>the</strong>ring place. Inaddition, adjacent streetscape improvementsre-established visual and physical connectionsamong <strong>the</strong> town’s three public realms – <strong>the</strong>river, church, and town hall.The project cost was €2.7 million. A8ernA wasawarded <strong>the</strong> European Prize for Urban PublicSpace in 2006.Urban DesignStakeholder input established <strong>the</strong> key projectobjective to create an open and simplemeeting place and public face for <strong>the</strong> town.This objective responded directly to A8’sA8ern8 Highway Section – Before (1970s to 2000s); an Albert Heijn grocery store opened under <strong>the</strong> highway along with o<strong>the</strong>rneighborhood retail (above).40<strong>Future</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gardiner</strong> <strong>Expressway</strong>

impact on <strong>the</strong> town fabric. A8 is a physicalbarrier between <strong>the</strong> north and south sides<strong>of</strong> town and <strong>the</strong> River Zaan. Aes<strong>the</strong>tically, itdetracts from <strong>the</strong> surrounding architecture andnatural landscape. Lastly, it diminishes use<strong>of</strong> public spaces next to <strong>the</strong> church and townhall.Program is key to achieving <strong>the</strong> projectobjective. A variety <strong>of</strong> uses were introducedinto <strong>the</strong> site, appealing to a range <strong>of</strong> townresident needs and interests. For this reason,A8ernA attracts residents <strong>of</strong> all ages.The retail program includes an Albert Heijnsupermarket, a pet shop, and flower shop aswell as 120 parking spaces. Albert Heijn, inparticular, was attracted to <strong>the</strong> site becauseit <strong>of</strong>fered a highway accessibility and a rareopportunity for a large floor plate in town.A skateboarding park, basketball courts, andping pong tables provide youth with recreationamenities. A graffiti gallery serves as a publicart component. A small marina with publicseating was constructed where A8 lifts over<strong>the</strong> Zaan, opening up river views.Material selection and surface treatmentmakes A8’s understory inviting and attractive.Structural columns were clad in a variety <strong>of</strong>materials, including herringbone-patternedtimber and reflective steel, into which backlitlettering is dye-cut. Similarly, groundtreatments – from timber decking to orangesurface paint – differentiate program spaces.ProcessThe A8ernA project was coordinated with alarger, city-wide planning effort to identifyredevelopment sites for 10 new squaresin Zaanstadt. Alternatives for at-grade ortunnel replacement <strong>of</strong> A8 were not seriouslyconsidered due to high costs.The Mayor and City Council, church <strong>of</strong>ficials,merchants, and residents participated in <strong>the</strong>planning process. Stakeholder objectivesand desires guided <strong>the</strong> design process. NLArchitects incorporated nearly all communityprogram requests into <strong>the</strong> final design.The businesses under A8 have been incrediblysuccessful. Albert Heijn has expressed interestin expanding and bringing in additional in-lineretail.Cladding and lighting on <strong>the</strong> highway columnsmakes <strong>the</strong> space more inviting; <strong>the</strong> skate-parkgenerates amble activity.lessons <strong>of</strong> a8ern8• A8ernA shows it is possible to live with an elevated structure.This project adapts a visually repetitive space (concrete overhead,evenly space piers) with programmatic and visual diversity. Theprovision <strong>of</strong> a density <strong>of</strong> small programs and spaces with differentcharacters makes an unappealing environment attractive.• A8ernA is a small scale project guided by a highly participatoryplanning process. The process illustrates that a full range<strong>of</strong> stakeholder desires can be incorporated into projectimplementation without diminishing design quality or resorting to<strong>the</strong> “lowest common denominator”.• The project was driven, in part, by private market interest inutilizing a unique retail site.A8ern8 Highway Section – After (Existing)SECTION V: Case studies 41

Case StudiesAmeliorateViaduct des Arts, Paris, FranceBackgroundThe Viaduct des Arts / Promenade Planteeis a 2-kilometer (1.25-mile) elevated railwaystructure in <strong>the</strong> 12th arrondissment <strong>of</strong> Paris.The viaduct runs parallel to Avenue Daumesnilwithin a dense residential neighborhood <strong>of</strong>five- to six-story buildings.The brick and masonry viaduct wasconstructed in <strong>the</strong> nineteenth century. Therailroad closed in 1969. From its closure to<strong>the</strong> late-1990s, <strong>the</strong> viaduct’s large archwayswere episodically occupied by assortments <strong>of</strong>antique shops, auto garages, used bookstores,and o<strong>the</strong>r uses.Atelier Parisien d’ Urbanisme (APUR), <strong>the</strong>city’s urban design agency, developed in <strong>the</strong>1980s an historic restoration strategy for <strong>the</strong>viaduct. The plan proposed re-tenanting <strong>the</strong>64 archways with artists, craftspeople, andrestaurants. In addition, it included a newlinear park and gardens overhead, whichwere designed by Philippe Mathieu andJacques Vergely. APUR partnered with alocal development corporation to identify andmanage new tenants.Whereas <strong>the</strong>re were studios and workshopsin <strong>the</strong> viaduct prior to renovation, <strong>the</strong> APURproject represented significant up-scaling <strong>of</strong>both <strong>the</strong> viaduct and Avenue Daumesnil.Urban DesignBy <strong>the</strong> 1980s <strong>the</strong> viaduct was considered anurban eyesore. Its shops did not contributepositively to neighborhood identity. In addition,<strong>the</strong> city had recently invested in <strong>the</strong> grandprojet, Opera Bastille. As such, <strong>the</strong> OperaBastille brought with it benefits for o<strong>the</strong>r arearedevelopment and public amenities. Theviaduct’s eventual restoration was intendedto enhance neighborhood retail, but also tocreate a contemporary Paris landmark.The viaduct and promenade designemphasizes <strong>the</strong> structure’s character andvisual connections to <strong>the</strong> city. The archwayrestoration, designed by Patrick Berger, isintended to minimally distract from <strong>the</strong>structure’s historic character. Glass claddingover <strong>the</strong> archways is set back in order toaccentuate <strong>the</strong> masonry, which was restored inViews <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> city below are a key element <strong>of</strong><strong>the</strong> Promenade design.The archways under <strong>the</strong> viaduct provide space for artist studios, workshops, and restaurants.42<strong>Future</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gardiner</strong> <strong>Expressway</strong>

<strong>the</strong> style <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Place des Vosges arcades. Thepromenade <strong>of</strong>fers a range <strong>of</strong> gardens – some<strong>of</strong> which enclose visitors in landscape, o<strong>the</strong>rsframe city views.At street-level, a six-meter-wide (20-feet) treelinedsidewalk separates <strong>the</strong> viaduct from athree-lane one-way street.The project also addresses railroadembankment reuse, though less successfully.At <strong>the</strong> viaduct’s eastern end, <strong>the</strong> promenadecontinues on an embankment. The restorationincludes new retail constructed along <strong>the</strong>embankment. The architecture here, however,is far less appealing than <strong>the</strong> restored viaduct.ProcessThe decision to retain and renovate <strong>the</strong> viaductwas guided by both design considerationsand strategic coordination with o<strong>the</strong>r planninginitiatives. APUR studied two alternativesin <strong>the</strong> 1980s – demolish and redevelopreclaimed land, or restore and create anelevated linear park.The park alternative was an opportunity tobuild upon <strong>the</strong> recently completed grandproject, <strong>the</strong> Opera Bastille, by adding ano<strong>the</strong>rnew public amenity. At <strong>the</strong> same time, <strong>the</strong>viaduct’s north side orients towards backs <strong>of</strong>existing buildings. Demolishing <strong>the</strong> viaductwould create <strong>the</strong> difficult task <strong>of</strong> integrating<strong>the</strong>se revealed buildings, now visuallyprominent, into <strong>the</strong> streetscape.Most importantly, <strong>the</strong> park alternative alignedwith APUR’s new agency focus on “greening<strong>the</strong> city”.The Viaduct des Arts and PromenadePlantee were advanced as two separate, butinterconnected projects. The Paris parksdepartment manages <strong>the</strong> Promenade. A localdevelopment corporation manages <strong>the</strong> archwayspaces and adjacent developments under an18-year lease.The dual-management structure is faultedfor <strong>the</strong> viaduct’s limited economic impact.Because two organizations manage <strong>the</strong>structure, a clear strategy has not be definedfor coordinating viaduct activities withneighborhood development and promoting itthroughout <strong>the</strong> city.lessons <strong>of</strong> viaduct des arts / promenade plantee• APUR advanced partnership with a local development corporationas a strategy for enhancing retail and residential development aswell as streng<strong>the</strong>ning <strong>the</strong> neighborhood’s identity.• The Promenade Plantee illustrates how potentially incompatibleprograms – when distributed on different levels – might co-existin <strong>the</strong> same place. The tranquil elevated linear park is separatedfrom <strong>the</strong> bustle <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> retail street below.• The Viaduct des Arts demonstrates a potential benefit to retainingexisting infrastructure. Containing new uses in an historicstructure creates a sense <strong>of</strong> connections between <strong>the</strong> past andpresent.• The Viaduct des Arts shows how existing infrastructure may besuccessfully integrated into <strong>the</strong> public realm.Some archways are left open to increasepedestrian connectivity within <strong>the</strong>neighborhood.The upper level <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> viaduct is a a 4 kilometer (2.5 miles) linear park.SECTION V: Case studies 43

Case StudiesAmeliorateEast River Esplanade, New York, NYBackgroundThe East River Esplanade is a planned3.2-kilometer-long (2-mile) series <strong>of</strong> publicspaces along <strong>the</strong> Lower Manhattan waterfrontand below F.D.R. Drive, an elevated highway.The F.D.R. was constructed in 1954. Thehighway extends over more than 125 cityblocks from Battery Park, north along <strong>the</strong> EastRiver to Harlem. In Lower Manhattan, it formsa barrier between downtown neighborhoodsand <strong>the</strong> waterfront. The Esplanade planningarea includes six waterfront districts, from<strong>the</strong> Financial District to <strong>the</strong> Lower East Side.The area is characterized by high-densitydevelopment – <strong>of</strong>fice towers to <strong>the</strong> south,“towers-in-<strong>the</strong>-park” housing development to<strong>the</strong> north.This project is one among many public realmand redevelopment efforts sponsored sinceSeptember 11th by <strong>the</strong> Lower ManhattanDevelopment Corporation, Department <strong>of</strong>City Planning, and Economic DevelopmentCorporation. Population in Lower Manhattanhas doubled – from 23,000 to 56,000 –in just eight years. The Esplanade is forthat reason linked to Lower Manhattan’stransformation into a residential neighborhoodand efforts to attract investment.SHoP and Ken Smith Landscape Architects,<strong>the</strong> City’s consultants, developed a planfor new programs, upland connections, andopen spaces on historic slips and piers. Newprogram pavilions under <strong>the</strong> F.D.R. andsurface treatments to its structure providea transition from Lower Manhattan to <strong>the</strong>waterfront.The project is funded by US $150 millionfrom <strong>the</strong> Lower Manhattan DevelopmentCorporation.Urban DesignThe F.D.R. poses development barriers at bothneighborhood and city scales. Within LowerManhattan, it reduces access to inter-modaltransportation – ferry and helicopter – andretail on East River piers. Improved access willmost directly benefit new area residents. AtRendering by SHoP <strong>of</strong> cladding, surfaces, plantings, and pavilions under F.D.R. Drive.44<strong>Future</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Gardiner</strong> <strong>Expressway</strong>

<strong>the</strong> same time, <strong>the</strong> Esplanade is one amongseveral new open spaces in New York Harbor,including Governor’s Island. The Esplanade isthus also considered a city-scale developmentstrategy.The Esplanade creates benefits at bothneighborhood and city scales throughconnections, program, and public realm.The design includes a diverse, yet visuallycoordinated streetscape and exteriorfurnishings palette. New seating, planters,arbors, and landforms upland create publicspaces and mark pedestrian paths to <strong>the</strong> river.The environment under <strong>the</strong> F.D.R. is alsoimproved so as to provide continuity <strong>of</strong> urbanactivity from upland neighborhoods to <strong>the</strong> river.New glass pavilions – 1,500 to 8,000 SF insize – are proposed to accommodate a range<strong>of</strong> retail, food, and community-requestedprograms. The underside <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> F.D.R. will beclad with a modular system <strong>of</strong> noise-abatingpanels and lighting. The design approachtreats <strong>the</strong> elevated structure as a “ro<strong>of</strong>”,creating a safe and inviting environment.The plan also addresses, in contrast to <strong>the</strong>Westway, ecological impacts on aquatic life.Existing piers will be renovated to increasewater flow through piles. Reef-balls will beinstalled at pile bases to encourage fishhabitat formation.ProcessThe purpose <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> project was primarilyesplanade design, and so highway removalalternatives were not considered in detail. TheEnvironmental Impact Statement proposed twoadditional alternatives.The first studied scenarios for building twoto six residential towers over <strong>the</strong> F.D.R.Construction feasibility and cost ruled out thisalternative. The second proposed replacing <strong>the</strong>F.D.R. with an at-grade boulevard.The F.D.R. has excess capacity in its LowerManhattan segment. However, accommodatingexisting capacity would require a six-laneat-grade boulevard – which would limitland available for <strong>the</strong> esplanade. There was<strong>the</strong>refore a trade-<strong>of</strong>f between <strong>the</strong> boulevardalternative and potential public space created.Though construction is publically funded, <strong>the</strong>Esplanade’s US $3.5 million operating budgethas a projected shortfall <strong>of</strong> 50 to 66 percent.lessons <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> east river esplanade• The Esplanade design embraced <strong>the</strong> elevated structure and itsform as an opportunity, leading to innovative approaches to publicrealm creation and a visually distinguished urban space.• This public amenity is created in <strong>the</strong> context <strong>of</strong> an existingcommuter population <strong>of</strong> hundreds <strong>of</strong> thousands, growingresidential population, and public and private investments.• The continued presence <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> F.D.R. increases development costsfor o<strong>the</strong>r waterfront sites. Construction costs for redevelopment <strong>of</strong>South Street Seaport, for example, were increased due to presence<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> elevated highway.Views <strong>of</strong> F.D.R. along <strong>the</strong> East River facingsouth towards Lower Manhattan.Rendering by SHoP <strong>of</strong> Esplandade south <strong>of</strong> Brooklyn Bridge.SECTION V: Case studies 45