evaluating blood films evaluating blood films - Hungarovet

evaluating blood films evaluating blood films - Hungarovet

evaluating blood films evaluating blood films - Hungarovet

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

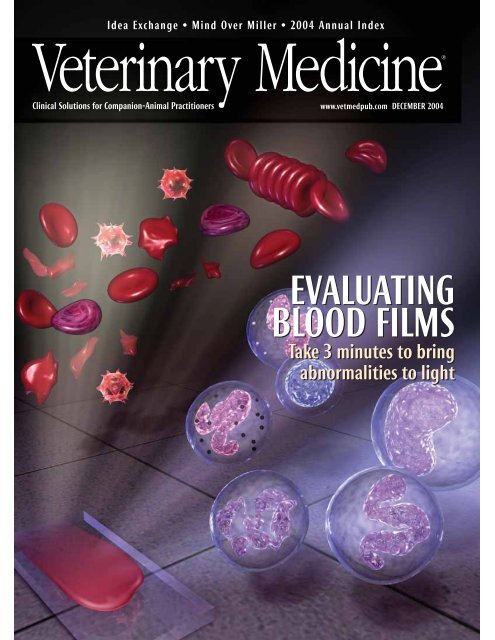

Idea Exchange • Mind Over Miller • 2004 Annual IndexClinical Solutions for Companion-Animal Practitionerswww.vetmedpub.com DECEMBER 2004EVALUATINGBLOOD FILMSTake 3 minutes to bringabnormalities to light1

Page 3Page 83814Symposium on a three-minuteperipheral <strong>blood</strong> film evaluationThree-minute peripheral <strong>blood</strong> film evaluation: Preparing the filmFred L. Metzger Jr. and Alan RebarNo single hematology procedure produces more valuable information yet requires so littletime and expense than a peripheral <strong>blood</strong> film. Proper preparation and staining of the filmare critical.Three-minute peripheral <strong>blood</strong> film evaluation: The erythron and thrombonFred L. Metzger Jr. and Alan RebarWhen examining the red <strong>blood</strong> cells and platelets in a <strong>blood</strong> film, ask yourself thesequestions to quickly identify and further characterize conditions such as anemia andthrombocytopenia.Three-minute peripheral <strong>blood</strong> film evaluation: The leukonFred L. Metzger Jr. and Alan RebarTaking a moment to briefly examine white <strong>blood</strong> cells will help you identify conditions suchas inflammation or stress that may indicate serious disease.PEER-REVIEWEDSymposium on a three-minuteperipheral <strong>blood</strong> film evaluationMYRIAM KIRKMAN-OH, KO STUDIOSMany veterinarians and technicians do not routinely evaluate <strong>blood</strong> <strong>films</strong> microscopically,largely because they lack confidence in either preparing a well-made <strong>blood</strong>film or in being able to accurately identify important abnormalities. But <strong>blood</strong> <strong>films</strong>should be evaluated whenever a complete <strong>blood</strong> count (CBC) is requested, regardless ofwhether the CBC is done in the clinic or at a reference laboratory. Blood film evaluation is asessential to a CBC as a microscopic examination of urine sediment is to a complete urinalysisor two views are to proper radiographic interpretation. No single hematology procedure producesmore valuable information yet requires so little additional time (we recommend threeminutes) and expense.Even the most expensive hematology analyzers are not designed to eliminate peripheral<strong>blood</strong> film evaluation. Morphologic features that instruments cannot identify include left shifts(increased immature neutrophils), neutrophil toxicity, lymphocyte reactivity, white <strong>blood</strong> cell(WBC) malignancy, red <strong>blood</strong> cell (RBC) poikilocytosis, RBC inclusions, and platelet abnormalities.A quick <strong>blood</strong> film review will help validate certain numerical data including plateletcounts, WBC counts, WBC differentials, and RBC density, since even reference laboratory analyzersprove inaccurate with some of the more abnormal samples.In this symposium, we suggest using a systematic method for <strong>evaluating</strong> <strong>blood</strong> <strong>films</strong>. Thismethod—which requires veterinarians and technicians to answer basic questions about RBC,WBC, and platelet numbers and morphology—maximizes hematologic information. And wecover the most common and important morphologic findings in the peripheral <strong>blood</strong>.We hope this symposium will provide veterinary practitioners and technicians with theskills to properly prepare, stain, and evaluate a peripheral <strong>blood</strong> film and will encouragethem to use this vital hematology tool in their practices.—Dr. Fred L. Metzger Jr.All articles have been reviewed by at least two board-certified specialists or recognized experts to ensure accuracy, thoroughness, and suitability.2

PEER-REVIEWEDThree-minute peripheral <strong>blood</strong> film evaluation:Preparing the filmNo single hematology procedure produces more valuable information yet requires so little time and expense than aperipheral <strong>blood</strong> film evaluation. Proper preparation and staining of the film are critical.Fred L. Metzger Jr., DVM, DABVP(canine and feline practice)Metzger Animal Hospital1044 Benner PikeState College, PA 16801Alan Rebar, DVM, PhD, DACVPDepartment of Veterinary PathobiologySchool of Veterinary MedicinePurdue UniversityWest Lafayette, IN 47907A PERIPHERAL BLOOD FILM evaluation should bepart of all complete <strong>blood</strong> counts (CBCs), regardlessof whether hematology is performedin-house or at a reference laboratory. Propersample collection, slide preparation, andstaining are essential to accurately evaluate a<strong>blood</strong> film, as is the correct use of a highqualitymicroscope. This article describes thesteps in preparing a <strong>blood</strong> film and theequipment you’ll need.Components of and indications for a CBCImportant components of a CBC include <strong>evaluating</strong>the erythron (hematocrit, total red <strong>blood</strong>cell [RBC] count, hemoglobin concentration,absolute reticulocyte count, and RBC indices),the leukon (total white <strong>blood</strong> cell [WBC] count,five-part differential count including immatureneutrophils), the thrombon (platelet countand platelet indices), and the total proteinconcentration. As mentioned earlier, alwaysinclude a peripheral <strong>blood</strong> film evaluation inthe CBC.A CBC should be included in evaluations ofevery sick patient, every patient with vaguesigns of disease, and every patient receivinglong-term medications. In addition, a CBCshould be performed as part of every preanestheticworkup, for adult wellness and geriatricprofiles, and as a recheck test for patients inwhich RBC, WBC, or platelet abnormalities werepreviously diagnosed.Collecting a sample for the <strong>blood</strong> filmArtifacts must be avoided for proper hematologicinterpretation. Causes of artifacts includepoor <strong>blood</strong> collection techniques, inadequatesample volumes, prolonged sample storage,and delayed sample analysis.Proper <strong>blood</strong> collection is vital to prevent erroneousresults from sample clotting and cellularlysis. Obtain hematology samples from thelargest <strong>blood</strong> vessel possible to minimize cellulartrauma and to prevent the activation of clottingmechanisms. For accurate results, discardclotted samples and collect fresh samples. Commonvenipuncture sites in dogs and cats includethe jugular, cephalic, and lateral and medialsaphenous veins. Anticoagulants includeEDTA, heparin, and citrate. EDTA is the preferredanticoagulant for <strong>blood</strong> film preparation becauseit preserves cellular detail better thanother anticoagulants do and does not interferewith Romanowsky staining of WBCs.Inadequate sample volume is a commoncause of inaccurate hematologic results. Properlyfill anticoagulated <strong>blood</strong> collection tubes toavoid falsely decreased hematocrits and cellcounts and to prevent RBC shrinkage.Hematologic samples must be analyzed assoon as possible to prevent artifacts created byexposure to anticoagulants and cell deteriorationdue to storage and shipment. Analyze sampleswithin three hours or refrigerate them at39.2 F (4 C) to avoid an artificially increasedhematocrit, increased mean corpuscular volume,and decreased mean corpuscular hemoglobinconcentration. 1 Prepare <strong>blood</strong> <strong>films</strong>within one hour of collection to avoid morphologicartifacts. RBC crenation, neutrophil hypersegmentation,lymphocytic nuclear distortion,and general WBC degeneration including vacuolizationin neutrophils may occur in agedsamples. In addition, monocyte vacuolization,monocyte cytoplasmic pseudopod formation,and platelet agglutination can be encounteredin stored samples. 2 If you use a reference laboratoryfor primary hematologic analyses, werecommend submitting freshly prepared <strong>blood</strong><strong>films</strong> along with the anticoagulated <strong>blood</strong>.3

FIGURE 1Good staining technique is criticalto identifying polychromatophilson a peripheral <strong>blood</strong> film.1. The steps in preparing a <strong>blood</strong> film. A small dropof <strong>blood</strong> is placed near the end of a slide (top). Aspreader slide is drawn back into the <strong>blood</strong> dropat a 30-degree angle (middle). Then the spreaderslide is pushed away from the <strong>blood</strong> drop,creating a uniform film across the slide (bottom).Producing high-quality <strong>blood</strong> <strong>films</strong> begins byusing clean, new slides. Used slides frequentlyhave imperfections such as scratchesand other physical defects. Slides must befree of fingerprints, dust, alcohol, detergents,and debris. Using a microhematocrit tube,place a small drop (2 to 3 mm in diameter)of well-mixed EDTA <strong>blood</strong> about 1 to 1.5 cmfrom the end of the slide. Next, draw aspreader slide back into the <strong>blood</strong> drop atabout a 30-degree angle until the spreaderslide edge contacts the sample drop and capillaryaction disperses the sample along theedge. Then, using a smooth steady motion,push the spreader slide away from the <strong>blood</strong>drop, creating a uniform film that coversnearly the entire length of the slide (Figure1). Changing the angle of the spreader slidewill change the length and thickness of the<strong>blood</strong> film. For <strong>blood</strong> samples with lowhematocrits (severe anemia), you may needto decrease the angle of the spreader slide tomake a good-quality slide. In contrast, forsamples with high hematocrits (severe dehydrationand polycythemia due to a variety ofconditions), you may need to increase theangle of the spreader slide.Drying is an important step in the productionof good-quality <strong>blood</strong> <strong>films</strong>. Allow the<strong>blood</strong> film to thoroughly air-dry before applyingstain, or use a heat block (at the low setting)or a hair dryer to hasten the drying time,thus minimizing refractile markings that candistort erythrocyte morphology. In addition,keep formalin and formalin-containing containersaway from all <strong>blood</strong> and cytologysmears to prevent staining artifacts such as increasedcytoplasmic granularity and basophilia.Staining the <strong>blood</strong> filmMost veterinary practices use a modifiedWright’s stain (Romanowsky stain) for bothhematology and cytology. Modified Wright’sstains are available as either three- or two-solutionkits. We prefer kits with three separatesolutions: an alcohol fixative, an eosinophilicstaining solution, and a dark-blue stainingsolution. Veterinary practices should havetwo separate Coplin stain jar sets—one forhematology and cytology samples and onefor contaminated samples such as those collectedfor ear and fecal cytology. For optimalresults, replace staining solutions regularly.Recommended <strong>blood</strong> staining protocolincludes dipping the air-dried slide five to10 times in each solution while blotting oneedge briefly in between each solution. Rinsethe slide with distilled water after the finalstaining step, and allow the <strong>blood</strong> film to airdrybefore examination. Good staining techniqueis critical to identifying polychromatophilson a peripheral <strong>blood</strong> film. If thestaining is done improperly, many of thequick Romanowsky-type stains will not givethe needed tinctorial differences between matureRBCs (orange-red) and polychromatophils(bluish-pink). Typically, poor staining withthe various quick stains results in all RBCs havinga bluish or muddy tint.Evaluating the <strong>blood</strong> filmThe microscopeA high-quality microscope is essential forhematology. We recommend a binocular microscopewith a minimum of 10, 20, and100 (oil-immersion) objectives and widefield10 oculars. When <strong>evaluating</strong> the slide,make sure maximum light reaches the <strong>blood</strong>film. This means positioning the substage condenseras close as possible to the stage withthe iris wide open. The light source should beequipped with a variable rheostat to allowmaximal control of light intensity. To ensureoptimal focused light for the microscopic evaluation,the microscope should be in Köhler il-Feathered edgeMonolayer MonolayerBody of <strong>blood</strong> filmApplication point2. The components of the peripheral <strong>blood</strong> film slide.FIGURE 2Label4

FIGURE 3 FIGURE 4 FIGURE 5Patient IDPatient IDPatient IDlumination. Contact your microscope vendor,or review the microscope manual to ensureproper illumination.The three zonesA good-quality <strong>blood</strong> film has threezones: the body (near the point of <strong>blood</strong> application),the monolayer (the zone betweenthe body and feathered edge), and the featherededge (the area most distant from thepoint of application) (Figure 2). The definitionof the monolayer varies from institutionto institution, but the definition used to ensureconsistent semiquantification of variousmorphologic abnormalities is the area whereabout half of the RBCs are touching one anotherwithout overlapping. The monolayer isthe area of the <strong>blood</strong> film where WBCs andplatelet numbers are estimated and cell morphologyis examined. Although the monolayeris the only zone where morphologicevaluation of individual cells is performed atoil-immersion magnification, systematic<strong>blood</strong> film evaluation includes assessing ofall three zones.First, examine the <strong>blood</strong> film at low magnification(10 or 20), and scan the entireslide to evaluate overall film thickness, celldistribution, and differentiation of the threedifferent zones. Evaluate the feathered edge(Figure 3) for microfilariae, phagocytized organisms,atypical cells, and platelet clumping.Next, examine the body of the <strong>blood</strong> film(Figure 4 ) for rouleau formation or RBC agglutination.Then, still using low magnification,evaluate the monolayer (Figure 5), estimatethe total WBC count (see the third article in thissymposium), and predict the expected WBCdifferential count. Finally, use the oil-immersionobjective (100) to examine RBC, WBC,and platelet morphology in the monolayer.Evaluate RBCs for evidence of anisocytosis,poikilocytosis, polychromasia, hemoglobinconcentration, and RBC parasites. ImportantRBC morphologic abnormalities include spherocytes,schistocytes, acanthocytes, and leptocytes(see the second article in thissymposium).Evaluate neutrophils for toxicity and thepresence or absence of a left shift (increasednumbers of band neutrophils). Evaluate lymphocytesfor reactivity and monocytes forphagocytized organisms (see the third articlein this symposium).With relatively little practice, you canidentify most important morphologic abnormalitiesin the RBCs, WBCs, and platelets withthe 20 objective field of view; these can bequickly validated with the 100 oil-immersionview.SummaryExamining a properly prepared peripheral<strong>blood</strong> film offers invaluable informationabout cellular morphologic changes not providedby automated instruments and providesa quality assurance confirmation of CBCdata generated by in-clinic or reference laboratoryhematology analyzers. We recommendtaking about three minutes to view the <strong>blood</strong>film and, using the questions discussed in thenext two articles of this symposium, to systematicallyevaluate the RBC, platelet, and WBCcomponents of the peripheral <strong>blood</strong> film.ACKNOWLEDGMENTThe authors gratefully acknowledge the technicalassistance and images provided by Dennis DeNicola,DVM, PhD, DACVP.3. Look for platelet clumps, microfilariae, and large cellsin the feathered edge of the film ( purple section).4. Look for rouleau formation and RBC agglutination inthe body of the film ( purple section).5. Estimate platelet and WBC counts and examine cellmorphology in the monolayer zone ( purple section).REFERENCES1. Willard, M. et al.: The complete <strong>blood</strong> countand bone marrow examination. Textbook ofSmall Animal Clinical Diagnosis by LaboratoryMethods, 3rd Ed. W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia,Pa., 1999; pp 11-30.2. Rebar, A.; Metzger, F.: The Veterinary CE Advisor:Interpreting Hemograms in Cats and Dogs.Vet. Med. (suppl.) 96 (12):1-12; 2001.5

PEER-REVIEWEDThree-minute peripheral <strong>blood</strong> film evaluation:The erythron and thrombonWhen examining the red <strong>blood</strong> cells and platelets in a <strong>blood</strong> film, ask yourself these questionsto quickly identify and further characterize conditions such as anemia and thrombocytopenia.Fred L. Metzger Jr., DVM, DABVP(canine and feline practice)Metzger Animal Hospital1044 Benner PikeState College, PA 16801Alan Rebar, DVM, PhD, DACVPDepartment of Veterinary PathobiologySchool of Veterinary MedicinePurdue UniversityWest Lafayette, IN 47907EVALUATING A PERIPHERAL <strong>blood</strong> film validates cellcounts performed by hematology analyzers,plus it offers valuable diagnostic information relayedby erythrocytes, platelets, and leukocytes.The first article in this symposium describedhow to prepare a peripheral <strong>blood</strong> film. In thisarticle, we discuss important red <strong>blood</strong> cell(RBC) and platelet number and morphologicchanges. And in the next article, we discusswhite <strong>blood</strong> cell (WBC) alterations.If a patient’s RBC mass is reduced, then thepatient is anemic. Once anemia is recognized,the next concern is bone marrow responsiveness:Is the anemia regenerative or nonregenerative?If the RBC bone marrow precursorcells respond with increasedproduction of appropriate magnitude,the anemia is regenerative (responsive). IfRBC production is not effectively increased,the anemia is nonregenerative (nonresponsive).Keep in mind that a lag of 48 to 72hours exists before bone marrow responsivenessis perceived in the peripheral <strong>blood</strong>, sobe careful in defining nonresponsiveness.Evaluating the thrombon by first assessingplatelet numbers is another important part ofevery complete <strong>blood</strong> count (CBC). Thrombocytopeniais more common than thrombocytosisand can be of great clinical importance. Plateletcounts below 40,000/µl can lead to spontaneousbleeding. Platelet clumping, which can be seenin any species but is particularly problematic incats, can give a falsely low platelet count.Platelet clumping frequently interferes with resultsfrom impedance cell counters because aggregatedplatelets may be included in the RBC orWBC counts, resulting in artifactually decreasedplatelet counts. 1Our approach to peripheral <strong>blood</strong> film evaluationuses a question-based format. This systematicapproach allows veterinary practitionersand technicians to maximize important visualinformation.Evaluating the RBCsIs there evidence of RBC regeneration? (Ispolychromasiaor reticulocytosis present?)In dogs and cats, polychromasia is the principalfeature of RBC regeneration on a <strong>blood</strong> filmprepared with Wright’s or modified Wright’sstain. Polychromatophils are immature RBCs thatstain bluish because they contain RNA (Figure 1).Polychromatophils on <strong>blood</strong> smears preparedwith Wright’s or modified Wright’s stain roughlycorrespond to reticulocytes on smears preparedwith new methylene blue stain. If regeneration isstill questionable after you’ve evaluated Wright’sstained<strong>blood</strong> <strong>films</strong>, perform a reticulocyte countwith new methylene blue stain.When performing reticulocyte counts in cats,it is important to count aggregate reticulocytes(cells containing diffuse accumulations of reticulum)since they represent recent RBC production1. Polychromatophils (arrows) in a dog (modifiedWright’s stain; 100).FIGURE 18

FIGURE 22. Aggregate (black arrows) and punctuate (red arrows)reticulocytes in a cat. Note that aggregatereticulocytes contain greater than or equal to fivebasophilic specks (new methylene blue stain; 100).4. A nucleated RBC (arrow) in a dog (modified Wright’sstain; 100).FIGURE 4in response to relatively severe anemia (Figure2). In cats, aggregate reticulocytes matureinto punctuate reticulocytes within 12 hours,and punctuate reticulocytes mature into RBCsin about 10 days. Consequently, elevatedpunctuate reticulocytes represent RBC regenerationtwo weeks earlier, whereas aggregatereticulocytes indicate recent regeneration. 2 Indogs and cats, peak reticulocyte counts occurfour to eight days after the onset of anemia.As a general guideline, a reticulocyte countabove 60,000/µl in cats (aggregate only) and80,000/µl in dogs indicates a regenerative anemia.3 Dogs with regenerative anemias havereticulocyte counts that are frequently 100,000to 300,000/µl (dogs with extremely regenerativeanemia can have counts of 500,000/µl orgreater), while cats typically demonstrate aless dramatic response when only the aggregatereticulocyte counts are evaluated.Reference laboratories can provide reticulocytecounts, and in some cases, they willautomatically add the reticulocyte count tothe CBC at an additional charge if anemia isidentified. The newer in-clinic, laser-basedhematology analyzers automatically provideabsolute reticulocyte counts with each CBC. 4Regenerative anemias can be further classifiedas either <strong>blood</strong> loss or hemolytic (decreasedRBC lifespan) anemias. Whenever yoususpect hemolysis, closely examine RBC morphologyto detect spherocytes, acanthocytes,schistocytes, RBC inclusions, and parasites (seebelow). Figure 3 is a flow chart for classifyinganemias in dogs and cats.Are nucleated RBCs present?Nucleated RBCs, or metarubricytes (Figure4), are not found in any appreciable numbersin mammalian peripheral <strong>blood</strong> samples. Mostclinicians consider fewer than 4 nucleatedRBCs/100 WBCs to be insignificant when theWBC count is within the reference range. NucleatedRBCs may be seen in increased numberswith strongly regenerative anemias, butthey should always be less numerous than thepolychromatophils or reticulocytes. This findinghas been identified as an appropriate nucleatedRBC response by some clinicians.An inappropriate nucleated RBC responseoccurs when more than 5 nucleated RBCs/100WBCs are present in the absence of polychromasia.Conditions associated with an inappropriatenucleated RBC response include bonemarrow stromal damage, extramedullaryhematopoiesis, fractures, hyperadrenocorticism,feline leukemia virus infection, chemotherapeuticdrug administration, and lead toxi-FIGURE 3Classifying Anemiasin Dogs and CatsWhen a patient has a decreased hematocrit, consider itshydration status and perform a reticulocyte count.The anemia is regenerative if the reticulocyte count is morethan 80,000/µl in dogs and more than 60,000/µl in cats.The anemia is nonregenerative if the reticulocyte count is less than80,000/µl in dogs and less than 60,000/µl in cats. In these cases,perform a serum chemistry profile, urinalysis, and other neededdiagnostic tests to rule out underlying diseases. If no such disease isfound, perform a bone marrow evaluation.Blood loss anemia is apossible cause. Look forexternal or internal hemorrhageorparasites (e.g. fleas,hookworms). Keep inmind that it takes oneto three days to see thehematocrit decrease.Hemolytic anemia is apossible cause. Considerimmune-mediatedhemolytic anemia withspherocytosis or Heinzbody hemolytic anemia(e.g. onion ingestion,acetaminophenadministration).If bone marrow hypoplasiais present, consideranemia of inflammation,anemia of chronic renaldisease, myelophthisisdue to bone marrow disease,or chemotherapytoxicosis.If bone marrow hyperplasiawith ineffectiveerythropoiesis is present,consider a nuclear maturationdefect (FeLV infection,drug toxicosis) or acytoplasmic maturationdefect (lead toxicosis,iron deficiency includingchronic <strong>blood</strong> loss).9

cosis, among others. 5 Splenic dysfunction (e.g.decreased clearance of circulating nucleatedRBCs) is an important cause of an inappropriaterelease of nucleated RBCs and may occur inpatients in which the spleen has been removedand in patients with splenic neoplasms,especially hemangiosarcoma.Is autoagglutination present?Agglutination is unorganized threedimensionalclumping of RBCs that must bedifferentiated from rouleau formation. It iscommon in dogs with immune-mediated hemolyticanemia. When confirmed, autoagglutinationsuggests an immune-mediatedprocess such as autoimmune-mediated hemolyticanemia or drug-induced hemolyticanemia (e.g. cephalosporins, penicillin) becauseRBC surface antibodies cause cell crosslinkingand the resulting agglutination.Rouleau formation is organized linear arraysof RBCs caused by decreased zeta potentialsfrom plasma proteins (e.g. globular proteins,fibrinogen) coating RBCs. This distinctiveformation is commonly described as stacks ofcoins. Unlike agglutination, which is a strongcross-linking between cells, rouleau is a resultof a weak binding between cells because ofdissimilar ionic charges on the RBC surface.Rouleau formation is a common finding whenfibrinogenesis is increased and must be differentiatedfrom agglutination. On routineWright’s-stained or modified-Wright’s-stained<strong>blood</strong> <strong>films</strong>, marked rouleau formation andagglutination may be difficult to differentiate.Whenever you suspect agglutination on a<strong>blood</strong> film, mix a drop of the well-mixed EDTAanticoagulated <strong>blood</strong> on a new glass slidewith two or more drops of isotonic saline solution.Add a cover slip, and view the mixtureas an unstained wet preparation. Under theseconditions, most rouleaux formations dissipatebut autoagglutination typically persists and isrecognized as clumped RBCs (Figure 5).Are poikilocytes present?Normal canine RBCs are shaped like biconcavedisks with prominent central pallor. FelineRBCs have much less apparent central pallor.Abnormally shaped RBCs are calledpoikilocytes and include artifactual changes(crenation) as well as true abnormalities (e.g.spherocytes, acanthocytes, schistocytes, leptocytes).Crenation (Figure 6 ) can be confusedwith important RBC changes such as acanthocytosis.Crenation is a shrinking artifact mostcommonly seen when less than optimalamounts of <strong>blood</strong> are collected into the EDTAtube and the peripheral <strong>blood</strong> film is notmade relatively quickly after the anticoagulationprocess. 4 Some less common causes ofcrenation include electrolyte disturbances,uremia, and rattlesnake envenomation. Auseful differentiating feature for identifyingcrenation is that crenation typically affectslarge numbers of cells in a particular area ofthe slide, whereas true poikilocytosis typicallyaffects relatively lower numbers of cellsthroughout the peripheral <strong>blood</strong> film. Crenationcan be minimized by preparing <strong>blood</strong><strong>films</strong> immediately after <strong>blood</strong> samples arecollected and properly anticoagulated.Spherocytes are spherical RBCs that havelost their normal biconcave shape, resulting inmore intense staining than normal RBCs. Theyhave no central zone of pallor, and they appearsmaller than normal RBCs (Figure 7 ).More than four to six spherocytes per 100field is considered elevated. Spherocytes arecommonly seen with many of the immunemediatedhemolytic anemias we encounter inveterinary medicine. Be careful when attemptingto identify spherocytes in feline RBCs becausefeline RBCs are much less biconcave thancanine RBCs and, therefore, have much lesscentral pallor.FIGURE 5FIGURE 6 FIGURE 7FIGURE 8 FIGURE 95. A saline wet preparation of canine <strong>blood</strong> showingautoagglutination (20).6. Crenation in a dog (modified Wright’s stain; 100).7. Spherocytes (black arrows) and a polychromatophil (redarrow) in a dog (modified Wright’s stain; 100).8. Acanthocytes (arrow) in a dog (modified Wright’s stain;100).9. Schistocytes (arrows) in a dog (modified Wright’s stain;100).10

FIGURE 10Acanthocytes are abnormally shaped RBCshaving two to 10 blunt, fingerlike surface projectionsof varying sizes (Figure 8). Thesemorphologic changes are related to abnormalaccumulation of lipids within the RBC membranewhen there is an abnormal plasmacholesterol:phospholipid ratio. Acanthocytesare seen occasionally in normal animals. Conditionsmost commonly associated with acanthocyteformation include underlying metabolicdiseases or diseases affecting normallipid metabolism. Nonneoplastic and neoplastic(hemangiosarcoma in particular) diseasesinvolving the liver, spleen, and kidney mayhave associated acanthocytosis in dogs and,occasionally, in cats. 6 Acanthocytosis is mostfrequently associated with liver disease andsplenic hemangiosarcoma.Schistocytes are RBC fragments formed bymechanical injury (Figure 9). Even in verylow numbers (one schistocyte in every threeto five 100 objective fields), schistocytes areclinically relevant. Finding even a few schistocytesmay help you identify underlying orsubclinical disseminated intravascular coagulation(DIC). Microvascular mechanical fragmentationof RBCs associated with diseasessuch as hemangiosarcoma and dirofilariasismay also result in schistocyte formation. 7A leptocyte (codocyte, target cell) is anRBC with excess cell membrane that forms ashape often referred to as having a Mexicanhat appearance (Figure 10). Leptocytes areseen occasionally in normal animals. Increasednumbers of leptocytes (> 3/100oil-immersion field) are expected with polychromasiabecause polychromatophils haveexcess membranes compared with normalRBCs. Consequently, leptocytosis is commonwhen reticulocytosis is present, so most referencelaboratories do not report this morphologicfinding. However, laboratories willreport leptocytes when they are seen in theabsence of polychromasia since the excesslipid membrane compared with cytoplasmicvolume is an abnormality. The two primarymechanisms causing this abnormal morphologyare either an upset in thecholesterol:phospholipid ratio in plasma resultingin lipid loading (as might be seenwith liver disease and other metabolic disorders)or a decrease in cytoplasmic contentcompared with normal (as might be seenwith iron deficiency typically due tochronic <strong>blood</strong> loss). 8 With iron deficiency,RBC hemoglobin content decreases, and inaddition to the leptocytosis, hypochromasiais often observed.Are RBC inclusions present?Accurately characterizing various inclusionsis an important aspect of <strong>blood</strong> filmevaluation. Inclusions may include Heinzbodies, basophilic stippling, Howell-Jollybodies, and certain infectious agents.Heinz bodies are localized accumulationsof denatured, oxidized, and precipitated hemoglobinin the RBC. They often affix to theinner RBC membrane and project from theRBC surface. Conditions associated withHeinz body hemolytic anemia include acetaminophentoxicosis in cats and acute onionand zinc toxicosis in dogs. Diabetes mellitus,hyperthyroidism, and lymphosarcoma in catsand the use of oral benzocaine sprays arealso associated with increased numbers ofHeinz bodies; but anemia is not present inthese cases. 8 The Heinz bodies observed incats may be small or not project from the cellsurface, making their identification difficult(Figure 11). New methylene blue stainingwill help confirm the presence of Heinzbodies; the Heinz bodies stain dark bluecompared with the rest of the erythrocyte(Figure 12). In contrast to Heinz bodies indogs, Heinz bodies can be an incidentalfinding in cats, and their relevance must bedetermined by <strong>evaluating</strong> clinical signs andother hemogram parameters.Basophilic stippling is seen inRomanowsky-stained <strong>films</strong> as small, dark-bluepunctate aggregates of residual ribosomes inRBCs (Figure 13). It has traditionally been associatedwith lead toxicosis in dogs but mayalso be associated with highly regenerativeanemias in any species. Further diagnostic investigationis important when basophilic stipplingis seen in the absence of reticulocytosis.Howell-Jolly bodies are small nuclearremnants that may be increased with acceler-FIGURE 11FIGURE 12FIGURE 1310. Leptocytes (arrow) in a dog (modified Wright’s stain;100).11. Heinz bodies, which are noselike RBC projections,(arrows) in a cat (modified Wright’s stain; 100).12. A <strong>blood</strong> film from a cat showing Heinz bodies; they areeasier to see with new methylene blue stain (100).13. Basophilic stippling (black arrow) and apolychromatophil (red arrow) in a dog (modifiedWright’s stain; 100).11

ated RBC regeneration. In healthy animals, thelow numbers of RBCs with Howell-Jolly bodiesreleased from the bone marrow are quicklyremoved from circulation primarily throughthe action of fixed tissue macrophages in thespleen. If Howell-Jolly bodies are easily identifiedand no reticulocytosis is noted, investigateunderlying splenic disease. This inclusioncan be an incidental finding in catsbecause of the open splenic architecture anddecreased erythrophagocytic properties inherentto the feline spleen.Infectious agents including Babesia (Figure14), Cytauxzoon, and Mycoplasma (previouslyknown as Haemobartonella) speciesmay be identified in RBCs. Evaluation for Mycoplasmaspecies (Figure 15) should be performedon freshly collected <strong>blood</strong> samplesthat have not been refrigerated to improveidentification.Evaluating the plateletsAre platelet numbers normal,decreased, or increased?Microscopic validation of platelet counts isan important component of <strong>blood</strong> film evaluation.Platelet clumping (Figure 16 ) interfereswith accurate enumeration of plateletswith all hematology analyzers and with manualcounting methods. Clumping occurs inmany samples because of platelet activationduring the collection process. Increasednumbers of large platelets may also result ininaccurate platelet counts when impedanceFIGURE 14counting methods are used.On a well-prepared peripheral <strong>blood</strong> filmin which no marked platelet clumping at thefeathered edge is present, the average numberof platelets observed per 100 oilimmersionmonolayer field multiplied by20,000 provides a good estimate of the numberof platelets/µl. As a general rule, youshould see a minimum of eight to 10 plateletsand a maximum of 35 to 40 platelets per100 oil-immersion monolayer field ofview. 9If the platelet numbers are decreased,can the mechanismbe determined?Thrombocytopenias occur through fourbasic mechanisms: sequestration, utilization(consumption), destruction, and decreased orineffective production. While clues as to theunderlying mechanism are found in the CBC,in most cases, bone marrow evaluation isneeded for complete interpretation.Sequestration thrombocytopenias are uncommonin veterinary medicine. They areusually the result of hypersplenism and,thus, are characterized by an enlargedspleen on physical or radiographic examination.Utilization, or consumption, thrombocytopeniasare caused by excessive activation ofthe coagulation cascade. These thrombocytopeniasare associated with inflammatory diseaseand DIC. Utilization thrombocytopeniasare usually moderate, with platelet numbersFIGURE 15in the 75,000 to 150,000/µl range, but valuesbelow 40,000/µl accompanied by petechiaeare possible. 10 Bone marrow evaluation revealsnormal to increased numbers ofmegakaryocytes.Destruction thrombocytopenias are immune-mediatedthrombocytopenias in whichnormal circulating platelets are destroyed bycirculating antiplatelet antibodies. Destructionthrombocytopenias are often extreme, with peripheralplatelet counts well below 50,000/µl.Bone marrow examination is characterized bynormal to increased numbers of megakaryocytes.Decreased or ineffective production is associatedwith extremely low platelet counts;counts well below 50,000/µl are common.Bone marrow evaluation will vary greatly inmost of these cases, although they will sharesimilar end results of deceased effective productionby the bone marrow. With decreasedproduction thrombocytopenias, no identifiableto extremely low numbers of megakaryocytesare present. With ineffective production, mostbone marrow samples have normal to increasednumbers of megakaryocytes, and theproduction of platelets is ineffective in manycases because of an immune-mediated destructiveprocess directed at an early stage ofplatelet development or at the megakaryocytepopulation itself.FIGURE 1614. Babesia canis (arrow) in a dog (modified Wright’sstain; 100).15. Mycoplasma haemocanis (arrow) in a dog (modifiedWright’s stain; 100).16. A <strong>blood</strong> film from a cat showing clumped platelets(arrow) (modified Wright’s stain; 20).12

If platelet numbers are increased,is the thrombocytosis reactiveor neoplastic?Most thrombocytosis is reactive or neoplastic.Reactive thrombocytosis can occursecondary to exercise, hemorrhage,splenectomy, excitement, fractures, high circulatingglucocorticoid concentrations,myelofibrosis, and iron deficiency anemiaas well as 24 hours or more after <strong>blood</strong>loss. 11 When the possible causes of reactivethrombocytosis have been ruled out,then the possibility of primary plateletleukemia must be considered. When extremelyhigh platelet counts are seen (>1,000,000/µl), thrombocytosis due to neoplasiamust be strongly considered.Are enlarged platelets present?The presence of enlarged platelets (Figure17 ), which correlates with increased meanplatelet volume (MPV), is supportive of an increasedrate of thrombopoiesis in the bonemarrow in response to a peripheral demand.This interpretation can be used with mostspecies; however, in cats, enlarged platelets isan equivocal finding.FIGURE 1717. A <strong>blood</strong> film from a dog with immune-mediatedhemolytic anemia. Note the enlarged platelets (blackarrows). Also note the polychromasia, spherocytosis, andHowell-Jolly body (red arrow) (modified Wright’s stain;100).ConclusionDetermining if an anemia is regenerative ornonregenerative is critical when developing alist of differential diagnoses. In addition, automatedplatelet counts should be verified byexamining <strong>blood</strong> <strong>films</strong> because plateletclumping is common, especially in cats,which results in artifactually decreasedplatelet counts.ACKNOWLEDGMENTThe authors gratefully acknowledge the technicalassistance and images provided by Dennis DeNicola,DVM, PhD, DACVP.REFERENCES1. Rebar A.H. et al.: Laboratory methods inhematology. A Guide to Hematology in Dogs andCats. Teton New Media, Jackson, Wyo., 2002; pp3-36.2. Duncan, J. et al.: Erythrocytes. VeterinaryLaboratory Medicine, 3rd Ed. Iowa State UniversityPress, Ames, 1994; pp 3-61.3. Feldman, B.F. et al.: Reticulocyte response.Schalm’s Veterinary Hematology, 5th Ed. LippincottWilliams & Wilkins, Baltimore, Md., 2000; pp110-116.4. Rebar A.H. et al.: Erythrocytes. A Guide toHematology in Dogs and Cats. Teton New Media,Jackson, Wyo., 2002; pp 30-68.5. Rebar, A.; Metzger, F.: The Veterinary CE Advisor:Interpreting Hemograms in Cats and Dogs.Vet. Med. (suppl.) 96 (12):1-12; 2001.6. Feldman, B.F. et al.: Classification and laboratoryevaluation of anemia. Schalm’s VeterinaryHematology, 5th Ed. Lippincott Williams &Wilkins, Baltimore, Md., 2000; pp 140-150.7. Rebar A.H. et al.: Platelets. A Guide to Hematologyin Dogs and Cats. Teton New Media,Jackson, Wyo., 2002; pp 113-134.8. Thrall, M.A.: Erythrocyte morphology. VeterinaryHematology and Clinical Chemistry. LippincottWilliams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa.,2004; pp 69-82.9. Duncan, J. et al.: Erythrocytes, leukocytes,hemostasis. Veterinary Laboratory Medicine, 3rdEd. Iowa State University Press, Ames, 1994; pp75-93.10. Harvey, J.W.: Platelets. Atlas of VeterinaryHematology: Blood and Bone Marrow of DomesticAnimals. W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia, Pa.,2001; pp 75-80.11. Feldman, B.F. et al.: Acquired platelet dysfunction.Schalm’s Veterinary Hematology, 5thEd, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore,Md., 2000; pp 496-500.13

PEER-REVIEWEDThree-minute peripheral <strong>blood</strong> film evaluation:The leukonTaking a moment to briefly examine white <strong>blood</strong> cells will help you identify conditionssuch as inflammation or stress that may indicate serious disease.Fred L. Metzger Jr., DVM, DABVP(canine and feline practice)Metzger Animal Hospital1044 Benner PikeState College, PA 16801Alan Rebar, DVM, PhD, DACVPDepartment of Veterinary PathobiologySchool of Veterinary MedicinePurdue UniversityWest Lafayette, IN 47907IN THE PREVIOUS ARTICLE, we discussed how toexamine the erythron and thrombon componentsof peripheral <strong>blood</strong> <strong>films</strong>. In this article,we again use a question-based format toguide you in <strong>evaluating</strong> the leukon by assessingwhite <strong>blood</strong> cell (WBC) numbers andmorphology. All five WBC cell types are assessed.Table 1 lists the general patterns ofWBC response under a variety of circumstances.Is the total WBC count elevated,normal, or decreased?Experience is required to accurately estimatecell counts directly from <strong>blood</strong> <strong>films</strong>. Subjectiveanalysis of total WBC numbers may beperformed by counting three to five 20 objectivefields; 10 to 20WBCs/20 field is considerednormal indogs and cats. Anothermethod involvescounting several100oil-immersion monolayerfields and multiplying the averagenumber of WBCs/100oil-immersion field by 2,000 toobtain a final estimated totalWBC count. 1Is a left shift present?A left shift may be the only indicator of activeinflammation in veterinary patients becausetotal WBC and neutrophil counts are frequentlywithin the reference range. Left shifts are characterizedby increased numbers of immatureneutrophils (e.g. band cells, metamyelocytes)in circulation. A left shift is a hallmark of inflammation,so accurately identifying bandcells is extremely valuable. No hematology analyzer(in-house or reference laboratory instrumentation)has been documented to accuratelyidentify band neutrophils; consequently,they must be identified microscopically. On<strong>blood</strong> <strong>films</strong>, the nucleus of a band neutrophiltypically has parallel sides (Figure 1), whereasthe nucleus of a mature neutrophil is distinctlysegmented. One useful approach to differentiateband neutrophils is to estimate the degreeof nuclear indentation. First, identify the narrowestand widest portions of the nucleus. Ifthe narrowest portion is less than one-third ofthe widest portion, the cell is classified as aband cell. 1Is there a monocytosis?The monocyte-macrophage continuum representsthe second major branch of the circulatingphagocyte system (neutrophils arethe first). Monocytes (Figure 2), unlike granulocytes(neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils),are released into the peripheral<strong>blood</strong> as immature cells and then differentiateinto phagocytic macrophages (Figure 3),epithelioid macrophages, or multinucleatedgiant cells.Monocytosis can be another indicator ofinflammation. It may be seen in both acuteand chronic conditions but may also be acomponent of stress leukograms. Conditionsfrequently associated with monocytosis includesystemic fungal diseases (histoplasmosis,blastomycosis, cryptococcosis, coccidioidomycosis,aspergillosis),14

FIGURE 5 FIGURE 65. Atypical lymphocytes in a dog (modified Wright’sstain; 100).6. Mild neutrophil toxicity in the form of cytoplasmicbasophilia in a cat (modified Wright’s stain; 100).7. Moderate neutrophil toxicity in the form of Döhlebodies (arrow) in a cat (modified Wright’s stain;100).8. Marked neutrophil toxicity in a dog. Note the cellulargiantism and basophilic, foamy, vacuolatedcytoplasm (modified Wright’s stain; 100).FIGURE 7 FIGURE 8Are toxic neutrophils present?Toxic neutrophils are a result of an acceleratedrate of neutrophil production in responseto inflammatory signals received bythe bone marrow. Toxic neutrophil changesinclude retention of cytoplasmic features ofimmaturity and include foamy basophiliccytoplasm (Figure 6 ) and small basophilicprecipitates known as Döhle bodies (Figure7 ). Döhle bodies are often present in lownumbers in normal cats, so, by themselves,they are a relatively equivocal finding; butDöhle bodies indicate serious toxicity indogs. 5 Other toxic changes include bizarrenuclear shapes and cellular giantism (Figure8).Systemic toxemia is often associated withbacterial endotoxins, but noninfectiouscauses also occur. Infectious diseases commonlyaccompanied by severe neutrophiltoxicity include feline pyothorax, pyometra,and severe canine prostatitis. Noninfectiouscauses associated with toxemia include immune-mediatedhemolytic anemia, acutepancreatitis, tissue necrosis, zinc and leadtoxicosis, and cytotoxic drug therapy. 616ConclusionEvaluating the five different WBC types iscritical when you develop a differential diagnosislist. Increases or decreases in neutrophils,eosinophils, basophils, lymphocytes,and monocytes should alert you toinvestigate certain conditions. For example,neutrophilic left shifts, persistenteosinophilia, and monocytosis are indicatorsof inflammation: Left shifts (increased numbersof immature, or band, neutrophils incirculation) indicate increased turnover andtissue use of neutrophils. Persistent peripheraleosinophilia indicates a systemic allergicor hypersensitivity reaction. And monocytosisis seen in peripheral <strong>blood</strong> when a demandfor phagocytosis is present.© Reprinted from VETERINARY MEDICINE, December 2004 Printed in U.S.A.ACKNOWLEDGMENTThe authors gratefully acknowledge the technicalassistance and images provided by Dennis DeNicola,DVM, PhD, DACVP.REFERENCES1. Rebar, A.; Metzger, F.: The Veterinary CE Advisor:Interpreting Hemograms in Cats and Dogs.Vet. Med. (suppl.) 96 (12):1-12; 2001.2. Duncan, J. et al.: Erythrocytes, leukocytes, hemostasis.Veterinary Laboratory Medicine, 3rd Ed.Iowa State University Press, Ames, 1994; pp 75-93.3. Willard, M. et al.: Leukocyte disorders. Textbookof Small Animal Clinical Diagnosis by LaboratoryMethods, 3rd Ed. W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia,Pa., 1999; pp 53-79.4. Rebar, A.H. et al.: Laboratory methods inhematology. A Guide to Hematology in Dogs andCats. Teton New Media, Jackson, Wyo., 2002; pp10-28.5. Willard, M. et al.: The complete <strong>blood</strong> countand bone marrow examination. Textbook ofSmall Animal Clinical Diagnosis by LaboratoryMethods, 3rd Ed. W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia,Pa., 1999; pp 11-30.6. Duncan, J. et al.: Erythrocytes, leukocytes, hemostasis.Veterinary Laboratory Medicine, 3rd Ed.Iowa State University Press, Ames, 1994; pp 75-93.Copyright Notice Copyright by Advanstar Communications Inc. Advanstar Communications Inc. retains all rights to this article. This article may only be viewed or printed (1) for personal use. User may notactively save any text or graphics/photos to local hard drives or duplicate this article in whole or in part, in any medium. Advanstar Communications Inc. home page is located at http://www.advanstar.com.IDEXX Part # 09-65274-00