Onchocerciasis - An Overview - Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences ...

Onchocerciasis - An Overview - Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences ...

Onchocerciasis - An Overview - Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences ...

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

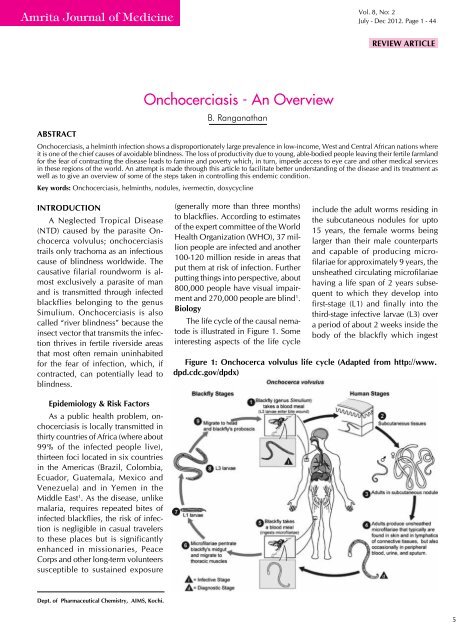

<strong>Amrita</strong> Journal <strong>of</strong> MedicineVol. 8, No: 2July - Dec 2012. Page 1 - 44REview ARTICLE<strong>Onchocerciasis</strong> - <strong>An</strong> <strong>Overview</strong>B. RanganathanAbstract<strong>Onchocerciasis</strong>, a helminth infection shows a disproportionately large prevalence in low-income, West and Central African nations whereit is one <strong>of</strong> the chief causes <strong>of</strong> avoidable blindness. The loss <strong>of</strong> productivity due to young, able-bodied people leaving their fertile farmlandfor the fear <strong>of</strong> contracting the disease leads to famine and poverty which, in turn, impede access to eye care and other medical servicesin these regions <strong>of</strong> the world. <strong>An</strong> attempt is made through this article to facilitate better understanding <strong>of</strong> the disease and its treatment aswell as to give an overview <strong>of</strong> some <strong>of</strong> the steps taken in controlling this endemic condition.Key words: <strong>Onchocerciasis</strong>, helminths, nodules, ivermectin, doxycyclineINTRODUCTIONA Neglected Tropical Disease(NTD) caused by the parasite Onchocercavolvulus; onchocerciasistrails only trachoma as an infectiouscause <strong>of</strong> blindness worldwide. Thecausative filarial roundworm is almostexclusively a parasite <strong>of</strong> manand is transmitted through infectedblackflies belonging to the genusSimulium. <strong>Onchocerciasis</strong> is alsocalled “river blindness” because theinsect vector that transmits the infectionthrives in fertile riverside areasthat most <strong>of</strong>ten remain uninhabitedfor the fear <strong>of</strong> infection, which, ifcontracted, can potentially lead toblindness.(generally more than three months)to blackflies. According to estimates<strong>of</strong> the expert committee <strong>of</strong> the WorldHealth Organization (WHO), 37 millionpeople are infected and another100-120 million reside in areas thatput them at risk <strong>of</strong> infection. Furtherputting things into perspective, about800,000 people have visual impairmentand 270,000 people are blind 1 .BiologyThe life cycle <strong>of</strong> the causal nematodeis illustrated in Figure 1. Someinteresting aspects <strong>of</strong> the life cycleinclude the adult worms residing inthe subcutaneous nodules for upto15 years, the female worms beinglarger than their male counterpartsand capable <strong>of</strong> producing micr<strong>of</strong>ilariaefor approximately 9 years, theunsheathed circulating micr<strong>of</strong>ilariaehaving a life span <strong>of</strong> 2 years subsequentto which they develop int<strong>of</strong>irst-stage (L1) and finally into thethird-stage infective larvae (L3) overa period <strong>of</strong> about 2 weeks inside thebody <strong>of</strong> the blackfly which ingestFigure 1: Onchocerca volvulus life cycle (Adapted from http://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx)Epidemiology & Risk FactorsAs a public health problem, onchocerciasisis locally transmitted inthirty countries <strong>of</strong> Africa (where about99% <strong>of</strong> the infected people live),thirteen foci located in six countriesin the Americas (Brazil, Colombia,Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico andVenezuela) and in Yemen in theMiddle East 1 . As the disease, unlikemalaria, requires repeated bites <strong>of</strong>infected blackflies, the risk <strong>of</strong> infectionis negligible in casual travelersto these places but is significantlyenhanced in missionaries, PeaceCorps and other long-term volunteerssusceptible to sustained exposureDept. <strong>of</strong> Pharmaceutical Chemistry, AIMS, Kochi.5

<strong>Amrita</strong> Journal <strong>of</strong> Medicinethe micr<strong>of</strong>ilariae during a bloodmeal from an infectedindividual.Clinical ManifestationsIt is the larvae (micr<strong>of</strong>ilariae) that cause most <strong>of</strong> theonchocerciasis symptoms in affected individuals. Sincethe larvae can migrate through the human body withoutprovoking an immune response, some onchocercainfectedpeople maybe without symptoms. Those withsymptoms will be characterized by one or more <strong>of</strong> thefollowing: typically itchy skin rashes, nodules underthe skin that provide a secure microenvironment forthe worms (skin manifestations) and vision changes(eye manifestations). A rather uncommon symptom isthe non-painful swelling <strong>of</strong> lymph glands.The intense and relentless itching, a subcutaneousinflammatory response to the dying micr<strong>of</strong>ilariae, resultsin dermatitis and the skin becoming swollen andchronically thickened, a condition called “lizard skin”.Additionally, the loss <strong>of</strong> elastic tissue in the skin givesit a “cigarette-paper” appearance. Over time, the skinmay take up an appearance commonly referred to as“leopard skin” wherein it loses some <strong>of</strong> its pigments, andon dark skin the features resemble the skin <strong>of</strong> a leopard 2 .Some micr<strong>of</strong>ilariae migrate to the eye - where they canbe found in all the internal tissues, except the lens - anddie there causing severe inflammation, bleeding andscarring. This initially results in reversible lesions mainlyon the cornea that progresses to permanent clouding <strong>of</strong>the cornea without proper treatment, ultimately resultingin blindness 3 . There can also be an inflammatoryevent in the optic nerve, primarily impairing peripheralvision, which, in turn progresses to full-blown blindness,if left untreated.DiagnosisThe most definitive diagnosis procedure involves theexamination for micr<strong>of</strong>ilariae in skin snip biopsies 4 . Typicallysix 1-2 mg shavings <strong>of</strong> the skin from different parts<strong>of</strong> the body are incubated in physiological saline solutionfor 24 hours upon which larvae promptly emergefrom the skin and can be microscopically visualized.Although this is a highly specific procedure and is consideredthe gold standard for diagnosing the infection,it lacks adequate sensitivity in low-intensity infections.In such cases, a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) <strong>of</strong> theskin snip can increase the sensitivity. However, thistechnology has yet to be commercialized.In patients with nodules in the skin, performing nodulectomyallows for identification <strong>of</strong> the micr<strong>of</strong>ilariae inthe tissue 4 . For epidemiological surveys, a non-invasiveprocedure - palpation for nodules - is employed. As acautionary note, this diagnostic aid must be judged agedependently:the proportion <strong>of</strong> palpable nodules is verylow in children, increases to about 30% in 10-year oldsand plateaus at about 40% in aged people 5 .In the optic manifestations <strong>of</strong> the infection, a slit-lampexamination <strong>of</strong> the anterior part <strong>of</strong> the eye can helpvisualize the larvae or the lesions they have caused 4 . Afew highly sensitive antibody tests have been developedfor diagnosing filarial infections in general. These testspromptly detect exposure <strong>of</strong> an individual to filaria butthey suffer from two main drawbacks viz. their lack <strong>of</strong>specificity in pinpointing the type <strong>of</strong> filarial infectionand their inability in determining past versus currentinfections 6 . More recently, several onchocerca-specificserological tests have been developed such as the OV-16antigen antibody test and the OV luciferase immunoprecipitationsystem (LIPS). However, these assays arecurrently only available in the research setting, are noteconomically viable in the mass-scale scenario requiredto address such infections and more importantly, are notyet approved as diagnostic tools.TREATMENTIt is desirable to initiate treatment for people whoare definitively diagnosed with onchocerciasis beforeit proceeds to cause debilitating and disfiguring skindisease, long-term pruritis and blindness. Before embarkingon therapy, however, it is common practiceto confirm co-infection with Loa loa, another filarialparasite endemic to the same regions as O. volvulus,as this helminth can be responsible for the severe sideeffects to the medications used to treat onchocerciasis.Standard TherapyWith the introduction <strong>of</strong> the broad-spectrumantiparasitic agent ivermectin by Merck in the mid-1980s, traditional anthelmintic drugs like suramin(characterized by multiple systemic toxicities) anddiethylcarbamazine (DEC which apparently acceleratesonchocercal blindness) have gradually run out <strong>of</strong> favourin treating o. volvulus infection. Apart from being thefirst safe and effective treatment for onchocerciasis,under the brand name Mectizan®, ivermectin is extensivelyused in veterinary practice in the United States(Stromectol®), Europe (Ivomec®) and in many othercountries for the control <strong>of</strong> endo- and ectoparasites indomestic animals 7 .Ivermectin: ChemistryCommercial ivermectin, the drug <strong>of</strong> choice foronchocerciasis, is a 4:1 mixture <strong>of</strong> semisynthetic hydrogenatedavermectins B1a and B1b which are members<strong>of</strong> a family <strong>of</strong> structurally complex antibiotics producedby fermentation <strong>of</strong> a strain <strong>of</strong> Streptomyces avermitilis.The structure (Figure 2), established by a combination6

<strong>Amrita</strong> Journal <strong>of</strong> Medicine<strong>Onchocerciasis</strong> - <strong>An</strong> <strong>Overview</strong><strong>of</strong> spectroscopic and x-ray crystallographic techniques,comprises a pentacyclic 16-membered macrocycle asthe aglycone linked to a disaccharide made <strong>of</strong> twooleandrose sugar residues 8 . The two components <strong>of</strong> themixture differ only by one carbon atom with B1a beinga higher homologue <strong>of</strong> B1b.Figure 2: Structure <strong>of</strong> ivermectinMode <strong>of</strong> ActionIvermectin destroys the larvae (micr<strong>of</strong>ilariae) that areresponsible for the skin as well as the eye manifestations<strong>of</strong> the infection. Although it does not kill the adult worms(macr<strong>of</strong>ilariae), it does sterilize the females and preventsthe release <strong>of</strong> micr<strong>of</strong>ilariae from the adult females residinginside the human host. Pharmacologically, the drugbinds and activates glutamate-gated chloride channels(GluCls) - invertebrate-specific members <strong>of</strong> the ligandgatedion channel (LGIC) family - inducing a tonicparalysis <strong>of</strong> the nematode musculature. Stimulation <strong>of</strong>the release <strong>of</strong> the inhibitory neurotransmitter gammaaminobutyricacid (GABA) in the nervous system <strong>of</strong> theworm is also attributed as another molecular mode <strong>of</strong>action 9 .PharmacokineticsIvermectin is usually administered orally as tabletswherein it exhibits good absorption 10 . Injections arealso available although the mass-scale administrationbefitting an endemic infection precludes the parenteralroute as a viable option. It is unable to cross themammalian blood-brain barrier (BBB) due to P-glycoprotein-mediatedefflux 11 . It is metabolized by hepaticCYP450, primarily by CYP3A4 is<strong>of</strong>orm, into at least tenhydroxylated and demethylated products 10 .Side Effects & ContraindicationsTreatment with ivermectin in humans has no majorside effects; the itching becomes more pronouncedwith therapy because <strong>of</strong> the death <strong>of</strong> the micr<strong>of</strong>ilariaebut this is not accompanied by worsening <strong>of</strong> the eyesymptoms. As alluded to earlier, people co-infectedwith loaiasis exhibit encephalitic reaction to ivermectintreatment which can be fatal. The drug is contraindicatedin children under five, or those who weigh less than15 kg. Clinical evidence <strong>of</strong> ivermectin therapy inpregnant women suggests that the risk <strong>of</strong> blindnessoutweighs the risk <strong>of</strong> ivermectin exposure after the firsttrimester with no detectable evidence <strong>of</strong> congenital abnormalitiesin children <strong>of</strong> ivermectin-treated mothers 12 .Evolving TherapyUse and safety <strong>of</strong> doxycycline - a well-establishedsemisynthetic member <strong>of</strong> the tetracycline group <strong>of</strong> antibiotics,introduced in the late-1960s by Pfizer - has beenreported in field trials 13 conducted in the mid-2000s forcontaining onchocerciasis. It destroys the endosymbioticricketssia-like Wolbachia bacteria crucial for theembryogenesis <strong>of</strong> o. volvulus that are resident in thereproductive tracts <strong>of</strong> the filarial nematodes 14 , therebymaking the worms sterile and consequently reducing thetransmission <strong>of</strong> the infection. A six-week oral regimen <strong>of</strong>doxycycline sterilizes 80-90% <strong>of</strong> the females 20 monthsafter treatment and almost completely eliminates therelease <strong>of</strong> micr<strong>of</strong>ilariae 15 .Since doxycycline does not kill the micr<strong>of</strong>ilariae,treatment with ivermectin should be given several daysprior to doxycycline therapy in order to provide symptomrelief to the patient 16 . Sufficient clinical data is notyet available to objectively comment on the safety <strong>of</strong>simultaneous treatment <strong>of</strong> onchocerciasis with these twoagents. As the mild side effects <strong>of</strong> ivermectin therapy areattributed to the increased death <strong>of</strong> the micr<strong>of</strong>ilariae anddoxycycline does not lead to the death <strong>of</strong> the larvae,the side effect pr<strong>of</strong>ile <strong>of</strong> doxycycline parallels its pr<strong>of</strong>ilewhen used conventionally as an antibacterial. Accordingto available data 17 , doxycycline administration inonchocerciasis patients co-infected with Loa loa is consideredsafe when the counts <strong>of</strong> the latter micr<strong>of</strong>ilariaein such individuals is less than 8000/ml. Doxyxcyclineis contraindicated in children under nine years <strong>of</strong> age,in pregnant and lactating women 18 .7

<strong>Amrita</strong> Journal <strong>of</strong> MedicineTable 1: Treatment regimens for Onchocerca volvulus infectionsDrug Adult Dose Pediatric DoseIvermectinDoxycycline150 μg/kg PO in one dose every 6months for 15 years200 mg PO daily for 6 weeks150 μg/kg PO in one dose every 6months for 15 years200 mg PO daily for 6 weeksThe typical dosage and duration <strong>of</strong> treatment usingthese agents is summarized in Table 1. It is importantto note that doxycycline is not standard therapy and itsapplication depends upon the opinion <strong>of</strong> the doctorin prescribing it as a treatment option. If the patientis unable to tolerate 200 mg <strong>of</strong> oral doxycycline dailythat is required to kill adult worms, 100 mg PO daily issufficient to sterilize female nematodes.PREVENTION & CONTROLThere are no vaccines or medications to preventgetting infected with o. volvulus. Personal protectionmeasures against insect bites are the only preventionefforts one can take to avoid the infection. These includewearing full-sleeve shirts and long pants duringthe day when blackflies bite, applying a spray or lotion<strong>of</strong> 30-50% <strong>of</strong> N,N-Diethyl-meta-toluamide (DEET) onexposed skin and wearing permethrin-treated clothing.Large-scale onchocerciasis control measures havebeen initiated and successfully operating for morethan three decades. Beginning in 1974, onchocerciasiscontrol program (OCP) for effective vector controlwas implemented in West Africa. With the availability<strong>of</strong> the inexpensive ivermectin (Mectizan®), MectizanDonation Program (MDP) was established in 1987to oversee Merck’s donation <strong>of</strong> the drug for effectivecontrol <strong>of</strong> onchocerciasis to needy communities worldwide.The enormous success <strong>of</strong> this program resultedin a partnership <strong>of</strong> GlaxoSmithKline with Merck whichsubsequently included elimination <strong>of</strong> lymphatic filariasiswithin the mandate <strong>of</strong> the MDP and began donatingalbendazole along with ivermectin. In 1992, a Non-Governmental Development Organization (NGDO)Coordination Group for onchocerciasis control wasformed under the supervision <strong>of</strong> WHO to promoteworldwide interest in and garner support for the use <strong>of</strong>ivermectin in endemic countries to eliminate this publichealth menace.Under the aegis <strong>of</strong> WHO, African Program for <strong>Onchocerciasis</strong>Control (APOC) was set up in 1995 witha goal <strong>of</strong> eliminating onchocerciasis as a disease <strong>of</strong>public health importance in Africa. Community-DirectedTreatment with Ivermectin (CDTI) involving active communityparticipation is at the core <strong>of</strong> APOC’s strategywith over one million Community Directed Distributors(CDDs) delivering over half a billion treatments in morethan 146,000 African communities since the inception<strong>of</strong> the program. This strategy has been so popular andeffective that it is now being extended to include delivery<strong>of</strong> other health interventions.The Carter Centre, a NGDO, has since 1996, assistednational Ministries <strong>of</strong> Health in eleven African andSouth/Central American countries by imparting healtheducation and distributing ivermectin. The centre is alsothe sponsoring agency for the <strong>Onchocerciasis</strong> EliminationProgram <strong>of</strong> the Americas (OEPA), a partnershipprogram including the governments <strong>of</strong> the six endemiccountries, Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), aprivate sector (Merck & Co. Inc.), a specialized researchinstitution (Centres for Disease Control and Prevention,CDC) and another NGDO, Lions Club InternationalFoundation. With the continued thrust under the OEPAumbrella 19 , the blindness attributable to the infection hasbeen eliminated from Colombia (2007), Ecuador (2009),followed by Mexico and Guatemala (2011); and theprogram efforts remain focused in Brazil and Venezuela.CONCLUSIONS<strong>Onchocerciasis</strong> was included on the priority diseaselist <strong>of</strong> VISION 2020, a global initiative for theelimination <strong>of</strong> avoidable blindness - a joint program <strong>of</strong>WHO and the International Agency for the Prevention<strong>of</strong> Blindness (IAPB) with an international membership<strong>of</strong> NGDOs, pr<strong>of</strong>essional associations, eye care institutionsand corporations. With the clearly demonstrablesuccess <strong>of</strong> burgeoning partnerships, it seems likely thatonchocerciasis shall be eliminated in most, if not in allthe endemic communities in the world 20 and the goal<strong>of</strong> removing this condition from the priority disease list<strong>of</strong> VISION 2020 seems increasingly within reach.REFERENCES1. Report <strong>of</strong> a WHO Expert Committee on onchocerciasiscontrol. WHO Technical Report Series 1995;852.2. Murdoch ME, Asuzu MC, Hagan M, et al. <strong>Onchocerciasis</strong>:the clinical and epidemiological burden <strong>of</strong> skin disease inAfrica. <strong>An</strong>n Trop Med Parasitol 2002;96:283-96.8

<strong>Amrita</strong> Journal <strong>of</strong> Medicine<strong>Onchocerciasis</strong> - <strong>An</strong> <strong>Overview</strong>3. Abiose A. Onchocercal eye disease and the impact <strong>of</strong> Mectizantreatment. <strong>An</strong>n Trop Med Parasitol 1998;92:Suppl(1):S11-22.4. Stingl P. <strong>Onchocerciasis</strong>: developments in diagnosis, treatmentand control. Int J Dermatol 2009;48:393-6.5. Duerr HP, Raddatz G, Eichner M. Diagnostic value <strong>of</strong> nodulepalpation in onchocerciasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg2008;102(2):148-54.6. Eberhard ML, Lammie PJ. Laboratory diagnosis <strong>of</strong> filariasis.Clin Lab Med 1991;11:977-1010.7. Beale JM Jr. <strong>An</strong>ti-infective agents. In: Block JH, Beale JM Jr,eds. Wilson and Gisvold’s textbook <strong>of</strong> organic medicinaland pharmaceutical chemistry, 11th ed.Baltimore:LippincottWilliams & Wilkins, 2004:264-7.8. Pampiglione S, Majori G, Petrangeli G, et al. Avermectins,MK-933 and MK-936 for mosquito control. Trans R Soc TropMed Hyg 1985;79(6):797-9.9. Yates DM, Wolstenholme AJ. <strong>An</strong> ivermectin-sensitiveglutamate-gated chloride channel subunit from Dir<strong>of</strong>ilariaimmitis. Int J Parasitol 2004;34(9):1075-81.10. Griffith RK. <strong>An</strong>thelmintics. In: Abraham DJ, ed. Burger’smedicinal chemistry and drug discovery - vol. 5, 6th ed.NewYork:John Wiley & Sons, 2003:1090-4.11. Borst P, Schinkel AH. What have we learnt thus far frommice with disrupted P-glycoprotein genes? Eur J Cancer1996;32(6):985-90.12. Dourmishev AL, Dourmishev LA, Schwartz RA. Ivermectin:pharmacology and application in dermatology. Int J Dermatol2005;44(12):981-8.13. Taylor MJ, Makunde WH, McGarry HF, et al. Macr<strong>of</strong>ilaricidalactivity after doxycycline treatment <strong>of</strong> Wuchereria bancr<strong>of</strong>ti:a double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial. Lancet2005;365(9477):2116-21.14. Hoerauf A, Mand S, Fischer K, et al. Doxycycline as anovel strategy against bancr<strong>of</strong>tian filariasis - depletion <strong>of</strong>Wolbachia endosymbionts from Wuchereria bancr<strong>of</strong>ti andstop <strong>of</strong> micr<strong>of</strong>ilaria production. Med Microbiol Immunol2003;192(4):211-6.15. Hoerauf A, Specht Y, Marfo-Debrekyei M, et al. Efficacy <strong>of</strong>5-week doxycycline treatment on adult Onchocerca volvulus.Parasitol Res 2009;104(2):437-47.16. Hoerauf A, Mand S, Adjei O, et al. Depletion <strong>of</strong> Wolbachiaendobacteria in Onchocerca volvulus by doxycyclineand micr<strong>of</strong>ilaridermia after ivermectin treatment. Lancet2001;357:1415-6.17. Wanji S, Tendongfor N, Nji T, et al. Community-directeddelivery <strong>of</strong> doxycycline for the treatment <strong>of</strong> onchocerciasisin areas <strong>of</strong> co-endemicity with loiasis in Cameroon. Parasites& Vectors 2009;2(39):1-10.18. Mitscher LA. <strong>An</strong>tibiotics and antimicrobial agents. In: WilliamsDA, Lemke TL, eds. Foye’s principles <strong>of</strong> medicinalchemistry, 5th ed.Philadelphia:Lippincott Williams &Wilkins, 2002: 857-60.19. Report <strong>of</strong> the 48th Directing Council <strong>of</strong> Pan American HealthOrganization. Toward the elimination <strong>of</strong> onchocerciasis(river blindness) in the Americas. Washington, D.C., August6, 2008.20. Thylefors, B, Alleman M. Towards the elimination <strong>of</strong> onchocerciasis.<strong>An</strong>n Trop Med Parasitol 2006;100:733-46.9