Achieving EQUITY for the Poor in Kenya: - Health Policy Initiative

Achieving EQUITY for the Poor in Kenya: - Health Policy Initiative

Achieving EQUITY for the Poor in Kenya: - Health Policy Initiative

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

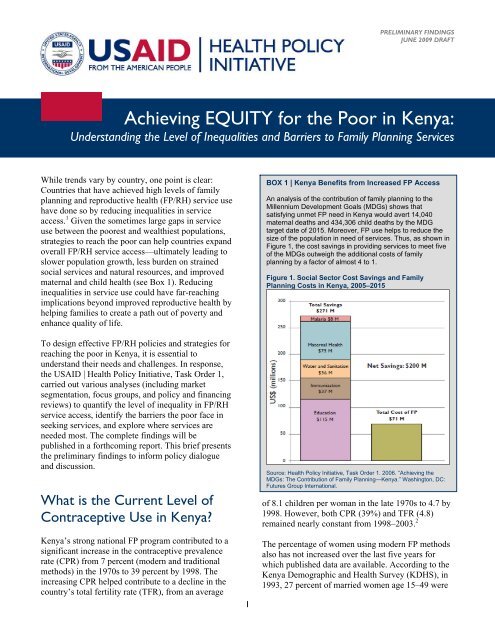

PRELIMINARY FINDINGSJUNE 2009 DRAFTDISCUSSIONBRIEF<strong>Achiev<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>EQUITY</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Poor</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Kenya</strong>:Understand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> Level of Inequalities and Barriers to Family Plann<strong>in</strong>g ServicesWhile trends vary by country, one po<strong>in</strong>t is clear:Countries that have achieved high levels of familyplann<strong>in</strong>g and reproductive health (FP/RH) service usehave done so by reduc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>equalities <strong>in</strong> serviceaccess. 1 Given <strong>the</strong> sometimes large gaps <strong>in</strong> serviceuse between <strong>the</strong> poorest and wealthiest populations,strategies to reach <strong>the</strong> poor can help countries expandoverall FP/RH service access—ultimately lead<strong>in</strong>g toslower population growth, less burden on stra<strong>in</strong>edsocial services and natural resources, and improvedmaternal and child health (see Box 1). Reduc<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>equalities <strong>in</strong> service use could have far-reach<strong>in</strong>gimplications beyond improved reproductive health byhelp<strong>in</strong>g families to create a path out of poverty andenhance quality of life.To design effective FP/RH policies and strategies <strong>for</strong>reach<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> poor <strong>in</strong> <strong>Kenya</strong>, it is essential tounderstand <strong>the</strong>ir needs and challenges. In response,<strong>the</strong> USAID | <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Initiative</strong>, Task Order 1,carried out various analyses (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g marketsegmentation, focus groups, and policy and f<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>greviews) to quantify <strong>the</strong> level of <strong>in</strong>equality <strong>in</strong> FP/RHservice access, identify <strong>the</strong> barriers <strong>the</strong> poor face <strong>in</strong>seek<strong>in</strong>g services, and explore where services areneeded most. The complete f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs will bepublished <strong>in</strong> a <strong>for</strong>thcom<strong>in</strong>g report. This brief presents<strong>the</strong> prelim<strong>in</strong>ary f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs to <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>m policy dialogueand discussion.What is <strong>the</strong> Current Level ofContraceptive Use <strong>in</strong> <strong>Kenya</strong>?<strong>Kenya</strong>’s strong national FP program contributed to asignificant <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> contraceptive prevalencerate (CPR) from 7 percent (modern and traditionalmethods) <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1970s to 39 percent by 1998. The<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g CPR helped contribute to a decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>country’s total fertility rate (TFR), from an average1BOX 1 | <strong>Kenya</strong> Benefits from Increased FP AccessAn analysis of <strong>the</strong> contribution of family plann<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong>Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) shows thatsatisfy<strong>in</strong>g unmet FP need <strong>in</strong> <strong>Kenya</strong> would avert 14,040maternal deaths and 434,306 child deaths by <strong>the</strong> MDGtarget date of 2015. Moreover, FP use helps to reduce <strong>the</strong>size of <strong>the</strong> population <strong>in</strong> need of services. Thus, as shown <strong>in</strong>Figure 1, <strong>the</strong> cost sav<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong> provid<strong>in</strong>g services to meet fiveof <strong>the</strong> MDGs outweigh <strong>the</strong> additional costs of familyplann<strong>in</strong>g by a factor of almost 4 to 1.Figure 1. Social Sector Cost Sav<strong>in</strong>gs and FamilyPlann<strong>in</strong>g Costs <strong>in</strong> <strong>Kenya</strong>, 2005–2015Source: <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Initiative</strong>, Task Order 1. 2006. “<strong>Achiev<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>the</strong>MDGs: The Contribution of Family Plann<strong>in</strong>g—<strong>Kenya</strong>.” Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC:Futures Group International.of 8.1 children per woman <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> late 1970s to 4.7 by1998. However, both CPR (39%) and TFR (4.8)rema<strong>in</strong>ed nearly constant from 1998–2003. 2The percentage of women us<strong>in</strong>g modern FP methodsalso has not <strong>in</strong>creased over <strong>the</strong> last five years <strong>for</strong>which published data are available. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong><strong>Kenya</strong> Demographic and <strong>Health</strong> Survey (KDHS), <strong>in</strong>1993, 27 percent of married women age 15–49 were

PRELIMINARY FINDINGSJUNE 2009 DRAFTus<strong>in</strong>g a modern method (e.g., oral pills, condoms,<strong>in</strong>trauter<strong>in</strong>e devices [IUDs], <strong>in</strong>jectables, implants,sterilization). CPR <strong>for</strong> modern methods <strong>in</strong>creased toabout 32 percent <strong>in</strong> 1998 and rema<strong>in</strong>ed at this levelthrough 2003. The percentage of women not us<strong>in</strong>gany method decreased from 67 percent <strong>in</strong> 1993 to 61percent <strong>in</strong> 1998, level<strong>in</strong>g off at just under 61 percent<strong>in</strong> 2003 (see Figure 2).The recent stagnation <strong>in</strong> contraceptive use and totalfertility fuels cont<strong>in</strong>ued rapid population growth,mak<strong>in</strong>g it difficult <strong>for</strong> <strong>Kenya</strong> to achieve its nationalsocioeconomic development goals.What Is <strong>the</strong> Level of Inequality<strong>in</strong> FP/RH Service Use?Def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g who “<strong>the</strong> poor” are is a challenge. Simplylook<strong>in</strong>g at <strong>in</strong>dicators such as <strong>the</strong> national poverty l<strong>in</strong>eis <strong>in</strong>adequate when try<strong>in</strong>g to determ<strong>in</strong>e how to ensurethat resources get to those most <strong>in</strong> need because, <strong>in</strong>many develop<strong>in</strong>g countries, a large proportion of <strong>the</strong>population lives below <strong>the</strong> poverty l<strong>in</strong>e. Recogniz<strong>in</strong>gthis, a qu<strong>in</strong>tile analysis is typically used. Oneapproach, popularized by <strong>the</strong> World Bank and MacroInternational, <strong>in</strong>volves divid<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> population <strong>in</strong>tofive equal groups based on an assessment ofsocioeconomic status (SES) accord<strong>in</strong>g to a standardof liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dex. This approach recognizes that factorso<strong>the</strong>r than <strong>in</strong>come, such as assets and householdamenities, contribute to <strong>the</strong> SES of families. Analysesus<strong>in</strong>g this method and data from <strong>the</strong> KDHS arepresented below.<strong>Poor</strong> Women Lack Access to Family Plann<strong>in</strong>g.Women from <strong>the</strong> lowest SES groups are <strong>the</strong> leastlikely to use modern contraceptive methods, and,from 1993–2003, <strong>Kenya</strong> made no progress <strong>in</strong> clos<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> gap <strong>in</strong> FP use between <strong>the</strong> low and high SESgroups (see Figure 3). In 2003, only 12 percent ofwomen from <strong>the</strong> very low SES group used a modernFP method while 45 percent of women from <strong>the</strong> veryhigh SES group did <strong>the</strong> same. Socioeconomic statusaffects access to and use of services, as <strong>the</strong>re is an 8–14 percentage po<strong>in</strong>t <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> modern contraceptiveprevalence use <strong>for</strong> each <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> qu<strong>in</strong>tile status.Unmet Need <strong>for</strong> Family Plann<strong>in</strong>g is Highest among<strong>the</strong> <strong>Poor</strong>. Unmet need refers to <strong>the</strong> proportion ofmarried women of reproductive age who want toFigure 2. Contraceptive Prevalence by Type ofMethod <strong>in</strong> <strong>Kenya</strong>, 1993–2003 (KDHS)% of married women age 15-4980604020067.327.35.561.0 60.731.5 31.57.5 7.81993 1998 2003Not us<strong>in</strong>g Modern Method Traditional MethodFigure 3. Modern CPR by Socioeconomic Status<strong>in</strong> <strong>Kenya</strong>, 1993–2003 (KDHS)% of married women 15-4960%50%40%30%20%10%0%1993 1998 2003Very Low Low Middle High Very HighFigure 4. Unmet FP Need by SocioeconomicStatus <strong>in</strong> <strong>Kenya</strong>, 2003 (KDHS)% of married women 15-4935%30%25%20%15%10%5%0%Unmet need <strong>for</strong>spac<strong>in</strong>gUnmet need <strong>for</strong>limit<strong>in</strong>gTotal unmet needVery Low Low Middle High Very High2

PRELIMINARY FINDINGSJUNE 2009 DRAFTwait two or more years to have a child, but are notus<strong>in</strong>g contraception. Reach<strong>in</strong>g women with unmetneed is often viewed as <strong>the</strong> “low hang<strong>in</strong>g fruit” <strong>in</strong>terms of expand<strong>in</strong>g FP access and <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g CPR,because this is a group that has already expressed adesire to space or limit future pregnancies and maybe more receptive to FP use than o<strong>the</strong>r non-users.In <strong>Kenya</strong>, women <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> very low, low, and middleSES groups have <strong>the</strong> highest level of unmet need <strong>for</strong>family plann<strong>in</strong>g (see Figure 4). In fact, total unmetFP need among women <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> very low (33%) andlow (30%) SES groups is nearly double <strong>the</strong> unmetneed found among <strong>the</strong> very high (17%) and high(17%) SES groups.Many of <strong>the</strong> FP Clients Served by <strong>the</strong> Public Sectorare Not <strong>Poor</strong>. Typically, public sector services are<strong>in</strong>tended to reach <strong>the</strong> groups who are most <strong>in</strong> needand are unable to af<strong>for</strong>d services elsewhere. In<strong>Kenya</strong>, <strong>the</strong> public health sector provides <strong>the</strong> majorityof FP plann<strong>in</strong>g services (53%). O<strong>the</strong>r providers<strong>in</strong>clude <strong>the</strong> commercial sector (e.g., private hospitals,pharmacies/chemists, and shops) (35%) and NGOs,religiously-affiliated cl<strong>in</strong>ics, mobile cl<strong>in</strong>ics, andcommunity-based distributors (11%). A look at <strong>the</strong>socioeconomic status of FP clients of <strong>the</strong> differentproviders shows that <strong>the</strong> very low and low SESgroups represent a small proportion of <strong>the</strong> clientele <strong>in</strong>all sectors (see Figures 5a–c). Most alarm<strong>in</strong>g,however, is <strong>the</strong> fact that <strong>the</strong>se groups account <strong>for</strong>only about one-fourth (26%) of <strong>the</strong> clients served by<strong>Kenya</strong>’s public sector, which, ideally, should cater to<strong>the</strong> needs of <strong>the</strong> poor. In practice, about half of <strong>the</strong>public sector’s clients are from <strong>the</strong> high (27%) orvery high (24%) SES groups.Socioeconomic Status Affects Reproductive andMaternal <strong>Health</strong>. Inequalities between <strong>the</strong> poorestand wealthiest groups are also evident <strong>in</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rreproductive and maternal health <strong>in</strong>dicators (seeTable 1). Among women <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> very low SES group,nearly half will marry by age 18 (45%) and twothirds(66%) will give birth be<strong>for</strong>e <strong>the</strong>y reach 20years of age. In contrast, about 8 <strong>in</strong> 10 women <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>very high SES group have a delayed marriage (age 18or older) and 7 <strong>in</strong> 10 have a delayed first birth (age20 or older). Women <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> lowest SES group arealso least likely to seek antenatal care (42%), have<strong>in</strong>stitutional deliveries (17%), or enjoy healthy birthspac<strong>in</strong>g (35%). These factors affect <strong>the</strong> health ofwomen and <strong>the</strong>ir children.Figure 5. Socioeconomic Status of FP Clienteleby Sector <strong>in</strong> <strong>Kenya</strong>, 2003 (KDHS)(a) Public Sector27 2423(b) NGO Sector3416(c) Commercial Sector20521317321011974Very lowLowMiddleHighVery highVery lowLowMiddleHighVery highVery lowLowMiddleHighVery highTable 1. Reproductive/Maternal <strong>Health</strong> Indicatorsby Socioeconomic Status <strong>in</strong> <strong>Kenya</strong>, 2003 (KDHS)Antenatal careInstitutionaldeliveryDelayedmarriage (atage 18 or older)Delayedchildbear<strong>in</strong>g(first birth atage 20 or older)Birth spac<strong>in</strong>g(36 months orlonger)VeryLow Low Middle High4217553335463372434353396844455955805948VeryHigh70778369543

PRELIMINARY FINDINGSJUNE 2009 DRAFTPeople say that users can deliver babies withtwo heads, and some report cont<strong>in</strong>uousheadaches and backaches which make a womanunable to work, such as plow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> land… Thisis <strong>the</strong> reason why I have not used, because Ihave to do a lot of hard work to feed mychildren. (Female discussant, rural poor,Nyanza)Male InvolvementWomen seek<strong>in</strong>g maternal and child health services ata hospital <strong>in</strong> Kisumu. Photo by Eric Ajwang.What Keeps <strong>the</strong> <strong>Poor</strong> fromAccess<strong>in</strong>g FP Services?The data above make clear that <strong>the</strong> poor are lesslikely to use FP services and also have <strong>the</strong> highestunmet need <strong>for</strong> family plann<strong>in</strong>g when compared too<strong>the</strong>r groups. Fur<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong>y are less likely to benefitfrom <strong>the</strong> health services <strong>in</strong>tended to meet <strong>the</strong>ir needs.To better understand <strong>the</strong> barriers faced by <strong>the</strong> poor,<strong>the</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Initiative</strong> conducted 33 focus groupdiscussions with members of urban and rural poorpopulations <strong>in</strong> Nyanza and Coast Prov<strong>in</strong>ces <strong>in</strong> <strong>Kenya</strong>.Participants <strong>in</strong>cluded women under age 30, both FPusers and non-users; women over age 30, both usersand non-users; and men. The project also <strong>in</strong>terviewed23 FP providers and conducted short exit <strong>in</strong>terviewswith 380 clients at selected sites. Barriers emerg<strong>in</strong>gfrom <strong>the</strong> prelim<strong>in</strong>ary analysis are summarized below.Mis<strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation and MisconceptionsMany of <strong>the</strong> focus group discussants knew at leastone method of family plann<strong>in</strong>g, and many recognized<strong>the</strong> benefits of family plann<strong>in</strong>g, especially <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong>health of women and children. Notwithstand<strong>in</strong>g,many participants only knew about certa<strong>in</strong> methodsand were unaware of o<strong>the</strong>r methods, such as femalecondoms and implants. Despite a high awareness ofsome FP methods, discussants held misconceptionsabout <strong>the</strong> use of family plann<strong>in</strong>g. These myths andmisconceptions typically related to potential sideeffects, such as pa<strong>in</strong>, <strong>in</strong>fertility, or birth defects. Insome cases, such beliefs were based on personalexperiences, but most often were based on reportsfrom relatives or community members.4In general, <strong>the</strong>re is limited communication aboutfamily plann<strong>in</strong>g between spouses. In urban areas,women who use contraceptives said <strong>the</strong>y do sobecause <strong>the</strong>y were motivated by friends or nurses, notby <strong>the</strong>ir husbands. Moreover, spousal opposition wasone of <strong>the</strong> key barriers mentioned <strong>in</strong> all <strong>the</strong>discussions. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to female and malediscussants, men oppose FP use because <strong>the</strong>y th<strong>in</strong>kwomen will become promiscuous, men want to havesons, or <strong>the</strong>y believe hav<strong>in</strong>g more children willultimately add to <strong>the</strong> wealth of <strong>the</strong> family. Womenwho use family plann<strong>in</strong>g might also be seen aschalleng<strong>in</strong>g men’s authority.The men do not like <strong>the</strong> idea of family plann<strong>in</strong>gbecause <strong>the</strong>y th<strong>in</strong>k that when we go to <strong>the</strong> cl<strong>in</strong>ic,we go to hide so that we may be promiscuous.(Female discussant, urban poor, Nyanza)When a woman unilaterally decides to usecontraceptives without <strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>m<strong>in</strong>g me, it meansshe is underm<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g my authority. (Malediscussant, urban poor, Nyanza)Sociocultural and Religious BarriersThe preferences <strong>for</strong> large families and <strong>for</strong> sons aredeeply held beliefs among members of <strong>the</strong>community, not only among men. For some men,<strong>the</strong>re is a competition with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> community to havelarger families as this is believed to be a sign ofstrength and virility of <strong>the</strong> man and also of <strong>the</strong>family’s wealth, as well as a guarantee that <strong>the</strong> familyl<strong>in</strong>eage will cont<strong>in</strong>ue. Women report that mo<strong>the</strong>rs-<strong>in</strong>law support <strong>the</strong> belief that wives are meant to bearchildren <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir sons. Women also said that hav<strong>in</strong>gmany children, especially sons, is a way to ensure<strong>the</strong>ir position or authority with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> family and tokeep <strong>the</strong>ir husbands from tak<strong>in</strong>g on additional wives.

PRELIMINARY FINDINGSJUNE 2009 DRAFTWhen you have children, a man can no longerthreaten you. (Female discussant, rural poor,Nyanza)Many discussants mentioned religion as a barrier, afact supported by <strong>the</strong> 2003 KDHS, <strong>in</strong> which 28percent of <strong>the</strong> poorest women said that religiousopposition is <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> reason <strong>for</strong> non-use of familyplann<strong>in</strong>g. Both Christian and Muslim discussants saidthat <strong>the</strong>ir religions prohibit FP use.It is prohibited <strong>in</strong> Islam, so I cannot support it.(Male discussant, urban poor, Nyanza)God <strong>for</strong>bids <strong>the</strong> use of contraception. It is likekill<strong>in</strong>g or a <strong>for</strong>m of abortion. (Older femalediscussant, rural poor, Nyanza)In some cases, discussants said that religious leadersare com<strong>in</strong>g out <strong>in</strong> support of family plann<strong>in</strong>g andused references to religious teach<strong>in</strong>gs to support thisview. For example, religious beliefs recognize thatfood is from God, but that it has limits. Thus,Christians are encouraged to use wisdom <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>irreproduction. Similarly, <strong>in</strong> Islam, it is desirous tohave only <strong>the</strong> number of children that one is able tocare <strong>for</strong>.Costs and Frequent StockoutsCosts <strong>for</strong> services <strong>in</strong>clude travel costs, lost wages orlost time <strong>for</strong> non-wage earners, costs <strong>for</strong> child care,and fees <strong>for</strong> services. The distances to health facilitiesare particularly prohibitive to residents of rural areas.Because to go to <strong>the</strong> health post is so far, wedon’t have money to go. Women also do nothave time to go. (Female discussant, ruralpoor, Coast)Costs are particularly burdensome <strong>for</strong> poor womenbecause of frequent stockouts of commodities.Women reported frustration at hav<strong>in</strong>g to pay travelcosts, lose wages, plead with neighbors to watch <strong>the</strong>irchildren, and/or take time away from <strong>the</strong>ir dailychores, only to reach <strong>the</strong> facility and learn that <strong>the</strong> FPcommodities or o<strong>the</strong>r needed supplies are notavailable.<strong>the</strong>ir confidentiality and avoid be<strong>in</strong>g seen bymembers of <strong>the</strong>ir own community.Respondents also reported hav<strong>in</strong>g to pay fees <strong>for</strong>services. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>Kenya</strong>n government policy,FP services <strong>in</strong> government facilities are to beprovided <strong>for</strong> free, as are government-supplied FPcommodities distributed by private and NGOproviders. However, clients might have to payregistration costs, fees <strong>for</strong> medical tests, and, <strong>in</strong> somecases, fees <strong>for</strong> commodities and o<strong>the</strong>r hidden fees,which are not uni<strong>for</strong>m across providers or evenwith<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> same facility. Most public health facilitiesreported that oral pills are free, but that Norplant(e.g., Kshs500), IUDs (e.g., Kshs200), and<strong>in</strong>jectables (e.g., Kshs50) <strong>in</strong>cur costs.Provider BehaviorSome discussants reported poor provider-client<strong>in</strong>teractions, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g limited counsel<strong>in</strong>g onavailable FP options and side effects as well ascondescend<strong>in</strong>g or unfriendly language. Providers alsoreported be<strong>in</strong>g overwhelmed by staff shortages andheavy workloads. In such cases, a provider noted, itis easier to provide <strong>the</strong> method <strong>the</strong> client asks than to<strong>in</strong>itiate a full counsel<strong>in</strong>g session. Even so, discussants<strong>in</strong> urban areas mentioned generally hav<strong>in</strong>g goodprovider-client <strong>in</strong>teractions.Where is <strong>the</strong> Need Greatest?The need to focus FP resources to reach <strong>the</strong> poor isclear. However, “<strong>the</strong> poor” are not a homogenousgroup. Differences <strong>in</strong> FP use can be seen across andwith<strong>in</strong> prov<strong>in</strong>ces, urban/rural areas, and SES groups.Figure 6. Contraceptive Prevalence Rate (AnyMethod) by Prov<strong>in</strong>ce (KDHS, 2003)However, distance and travel costs were not a barrier<strong>for</strong> all discussants, as some reported choos<strong>in</strong>g to gofar<strong>the</strong>r to receive <strong>the</strong> services <strong>the</strong>y want or to protect5

PRELIMINARY FINDINGSJUNE 2009 DRAFTTable 2. Current FP Use and Unmet Need among Married Women (age 15–49) by Prov<strong>in</strong>ce, 2003 (KDHS)NationalProv<strong>in</strong>ceTotal Urban Rural Nairobi Central Coast Eastern Nyanza RiftValleyWesternNorthEasternCurrent UseAny method (%)39483751662451253434

Discussion: The <strong>EQUITY</strong> ApproachPRELIMINARY FINDINGSJUNE 2009 DRAFTand relative wealth with urban areas, as even with<strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong>se areas, <strong>the</strong>re are segments of <strong>the</strong> urban and ruralpoor that are <strong>in</strong> greatest need of services. TheWhile overall improvements <strong>in</strong> healthcare systemsprelim<strong>in</strong>ary analysis of <strong>in</strong>equalities <strong>in</strong> FP useare desirable <strong>in</strong> most develop<strong>in</strong>g countries,presented <strong>in</strong> this brief shows that <strong>the</strong> lowest SESexperience has shown that health <strong>in</strong>terventions willgroups are least likely to use family plann<strong>in</strong>g and alsonot reach <strong>the</strong> poorest groups without appropriateplann<strong>in</strong>g, target<strong>in</strong>g, and oversight. 3have <strong>the</strong> highest unmet FP need.Care must betaken to identify <strong>the</strong> poor, understand <strong>the</strong>ir needs, andnderstand<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> barriers to service accessassess <strong>the</strong>ir barriers to <strong>in</strong>creased service access andUand use—Once <strong>the</strong> level of <strong>in</strong>equalit y is known,use. Build<strong>in</strong>g on this evidence, governments shouldpolicymakers must have an understand<strong>in</strong>g of why <strong>the</strong><strong>for</strong>mulate targeted, pro-poor policies as <strong>the</strong><strong>in</strong>equalities exist. The focus group discussionsfoundation of appropriate, responsive programs.summarized <strong>in</strong> this prelim<strong>in</strong>ary brief have identified“Target<strong>in</strong>g” directs scarce resources to those most <strong>in</strong>need. 4key barriers such as mis<strong>in</strong><strong>for</strong>mation andA “pro-poor” approach means that healthcaremisconceptions, lack of constructive malecosts are based on <strong>the</strong> client’s ability to pay; <strong>the</strong> poorengagement, sociocultural and religious beliefs,and nearly poor are protected from f<strong>in</strong>ancial calamityhidden costs <strong>for</strong> services, and <strong>in</strong>adequate quality ofdue to a severe illness; and steps are taken to improvecare. These discussion f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs can complementequitable access—both <strong>in</strong> terms of quality and <strong>the</strong>exist<strong>in</strong>g data from <strong>the</strong> DHS to fur<strong>the</strong>r explore reasonsgeographic distribution of services. 5<strong>for</strong> non-use of family plann<strong>in</strong>g.The <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Initiative</strong> has designed <strong>the</strong>ntegrat<strong>in</strong>g equity goals <strong>in</strong>to policies, plans, and<strong>EQUITY</strong> Approach to ensure that health policiesIstrategies—Several countries, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Kenya</strong>,meet <strong>the</strong> needs of <strong>the</strong> poor. The approach calls <strong>for</strong>:aspire to alleviate poverty. To make this happen,specific policies, goals, strategies, resources, andngag<strong>in</strong>g and empower<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> poor—The poormonitor<strong>in</strong>g mechanisms are needed. In <strong>Kenya</strong>, <strong>the</strong>E should be empowered to become <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong><strong>Health</strong> <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Initiative</strong> has provided technicaldecisions that affect <strong>the</strong>ir healthcare needs. They aresupport to <strong>the</strong> government and <strong>in</strong>-country partners tobest able to speak to <strong>the</strong> challenges <strong>the</strong>y face and todraft <strong>the</strong> new National Reproductive <strong>Health</strong> Strategy.provide <strong>in</strong>sights to design appropriate solutions.The strategy calls <strong>for</strong> <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g “equitable access toThus, <strong>the</strong> poor have an important role to play <strong>in</strong>reproductive health services” and <strong>in</strong>cludes specific,problem identification, advocacy, plann<strong>in</strong>g, andtime-bound goals to: (1) reduce unmet FP needmonitor<strong>in</strong>g. In <strong>Kenya</strong>, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Initiative</strong>among <strong>the</strong> poor by 20 percent by 2015; and (2)<strong>in</strong>volved <strong>the</strong> poor <strong>in</strong> problem identification through<strong>in</strong>crease modern CPR among <strong>the</strong> poor by 20focus group discussions. The project has also workedpercentage po<strong>in</strong>ts by 2015 (up from 12% <strong>in</strong> 2003).with <strong>in</strong>-country partners to organize policy dialoguebetween <strong>the</strong> poor and <strong>the</strong>ir representatives andarget<strong>in</strong>g resources and ef<strong>for</strong>ts to reach <strong>the</strong>regional stakeholders <strong>in</strong> Nyanza Prov<strong>in</strong>ce. Fur<strong>the</strong>rTpoor—Integrat<strong>in</strong>g equity goals <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> nationaldissem<strong>in</strong>ation of f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs from <strong>the</strong> focus groupstrategy is a positive step <strong>for</strong>ward, and one that mustdiscussions has taken place at <strong>the</strong> community level <strong>in</strong>be followed up with implementation and monitor<strong>in</strong>gKisumu, Homa Bay, and Siaya Districts. Throughmechanisms. The need of <strong>the</strong> hour is to target<strong>the</strong>se <strong>for</strong>ums, <strong>the</strong> poor shared <strong>the</strong>ir views toward FPresources to reach areas of extreme poverty, such asuse and ways to improve service access.North Eastern and Nyanza Prov<strong>in</strong>ces, and <strong>the</strong> dry(and poor) nor<strong>the</strong>rn parts of <strong>the</strong> country. Similarly,uantify<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> level of <strong>in</strong>equality <strong>in</strong> healthcareQ<strong>the</strong>re is a need to allocate resources to areas withaccess and health status—Gett<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> FP/RHpastoralist populations and to <strong>the</strong> urban slums <strong>in</strong>needs of <strong>the</strong> poor on <strong>the</strong> national policy agenda firstmajor cities. The country should also design a healthrequires an understand<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> magnitude andf<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>g strategy to ensure f<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> poor asurgency of <strong>the</strong> issue. Market segmentation analyseswell as streng<strong>the</strong>n and monitor <strong>the</strong> implementation ofbased on DHS data and poverty mapp<strong>in</strong>g can revealexist<strong>in</strong>g fee exemption policies.<strong>the</strong> level of <strong>in</strong>equality and help to p<strong>in</strong>po<strong>in</strong>t areas ofgreatest need. In particular, it is important toield<strong>in</strong>g public-private partnerships <strong>for</strong>recognize that <strong>the</strong> poor are not a homogenous group.Yequity—Meet<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> FP/RH needs of <strong>the</strong> poorIt is not enough to equate poverty with rural areas7

PRELIMINARY FINDINGSJUNE 2009 DRAFTrequires that countries make <strong>the</strong> best use of all <strong>the</strong>available public, private, donor, and NGO resources.As discussed above, <strong>the</strong> poor <strong>in</strong> <strong>Kenya</strong> account <strong>for</strong>only about one-fourth of <strong>the</strong> clients of public healthfacilities. Strategies are needed to ensure thatsubsidized services (through <strong>the</strong> government orNGOs) reach <strong>the</strong> poorest populations and that <strong>the</strong>private sector serves clients that are more able to pay<strong>for</strong> services. The country should streng<strong>the</strong>n publicprivatepartnerships with <strong>the</strong> commercial sector, andexplore <strong>in</strong>novative models with NGOs—such ascommunity-based distribution, which worked well <strong>in</strong><strong>Kenya</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> past—to reach underserved populations.Community discussions on family plann<strong>in</strong>g use among <strong>the</strong>poor <strong>in</strong> Siaya District. Photo by Eric Ajwang.ConclusionFor <strong>the</strong> poor, lack of access to family plann<strong>in</strong>g andcont<strong>in</strong>ued high fertility can mean fewer resources(e.g., money, time, attention) <strong>for</strong> each child, lead<strong>in</strong>gto poor nutrition, ill health, and limited educationalopportunities—ultimately trapp<strong>in</strong>g this group <strong>in</strong> apoverty cycle. For <strong>the</strong> society, cont<strong>in</strong>ued rapidpopulation growth will hamper <strong>Kenya</strong>’s ability tomeet <strong>the</strong> needs of its citizens and atta<strong>in</strong> its health anddevelopment goals, such as those conta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>Vision 2030 and MDGs. A range of policy andf<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>itiatives should be implemented to ensurethat <strong>the</strong> poor have equitable access to FP/RHservices. 6 No one strategy or program will expandaccess <strong>for</strong> all <strong>the</strong> poor and vulnerable groups <strong>in</strong><strong>Kenya</strong>, underscor<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> need to address poverty andequity from multiple angles. Do<strong>in</strong>g so will not onlybenefit <strong>the</strong> poor, but also <strong>the</strong> society as a whole.FOR MORE INFORMATION<strong>Health</strong> <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Initiative</strong>, Task Order 1Futures Group InternationalThe Chancery Build<strong>in</strong>g, 3rd FloorValley Road, PO Box 3170Nairobi, <strong>Kenya</strong> 00100Tel: 254.20.2723951 / 254.20.2723952Web: http://www.healthpolicy<strong>in</strong>itiative.comThis brief was prepared by Task Order 1 of <strong>the</strong> USAID |<strong>Health</strong> <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Initiative</strong>. It was produced <strong>for</strong> review by <strong>the</strong> U.S.Agency <strong>for</strong> International Development (USAID). The viewsexpressed <strong>in</strong> this publication do not necessarily reflect <strong>the</strong>views of USAID or <strong>the</strong> U.S. Government.Task Order 1 is implemented by <strong>the</strong> Futures GroupInternational, <strong>in</strong> collaboration with <strong>the</strong> Centre <strong>for</strong>Development and Population Activities (CEDPA), WhiteRibbon Alliance <strong>for</strong> Safe Mo<strong>the</strong>rhood (WRA), Futures Institute,and Religions <strong>for</strong> Peace.ENDNOTES1 <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Initiative</strong>, Task Order 1. 2007. Inequalities <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Use of Family Plann<strong>in</strong>g and Reproductive <strong>Health</strong>Services: Implications <strong>for</strong> Policies and Programs. Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC: Futures Group International, <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Initiative</strong>, Task Order 1.2 Based on <strong>the</strong> 1977/78 <strong>Kenya</strong> Fertility Survey (KFS), and <strong>the</strong> 1989, 1993, 1998, and 2003 <strong>Kenya</strong> Demographic and <strong>Health</strong> Surveys(KDHS).3 Gwatk<strong>in</strong>, D.R. 2004. “Are Free Government <strong>Health</strong> Services <strong>the</strong> Best Way to Reach <strong>the</strong> <strong>Poor</strong>?” <strong>Health</strong>, Nutrition, and Population (HNP)Discussion Paper. Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC: World Bank.4 POLICY Project. 2003. “Target<strong>in</strong>g: A Key Element of National Contraceptive Security Plann<strong>in</strong>g.” <strong>Policy</strong> Issues <strong>in</strong> Plann<strong>in</strong>g and F<strong>in</strong>anceNo. 3. Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC, Futures Group International, POLICY Project.5 Bennett, S. and L. Gilson. 2001. <strong>Health</strong> F<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>g: Design<strong>in</strong>g and Implement<strong>in</strong>g Pro-poor Policies. London: Department <strong>for</strong> InternationalDevelopment (DFID) <strong>Health</strong> Systems Resource Center.6 <strong>Health</strong> <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Initiative</strong>, Task Order 1. 2007. “Approaches That Work: <strong>Health</strong> Equity.” Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, DC: Futures Group International,<strong>Health</strong> <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>Initiative</strong>, Task Order 1.8