Exploring Links between Trafficking and Migration - Global Alliance ...

Exploring Links between Trafficking and Migration - Global Alliance ...

Exploring Links between Trafficking and Migration - Global Alliance ...

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

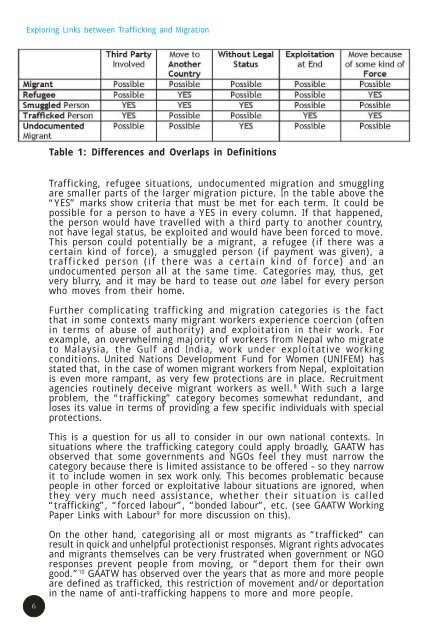

<strong>Exploring</strong> <strong>Links</strong> <strong>between</strong> <strong>Trafficking</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Migration</strong>Table 1: Differences <strong>and</strong> Overlaps in Definitions<strong>Trafficking</strong>, refugee situations, undocumented migration <strong>and</strong> smugglingare smaller parts of the larger migration picture. In the table above the“YES” marks show criteria that must be met for each term. It could bepossible for a person to have a YES in every column. If that happened,the person would have travelled with a third party to another country,not have legal status, be exploited <strong>and</strong> would have been forced to move.This person could potentially be a migrant, a refugee (if there was acertain kind of force), a smuggled person (if payment was given), atrafficked person (if there was a certain kind of force) <strong>and</strong> anundocumented person all at the same time. Categories may, thus, getvery blurry, <strong>and</strong> it may be hard to tease out one label for every personwho moves from their home.Further complicating trafficking <strong>and</strong> migration categories is the factthat in some contexts many migrant workers experience coercion (oftenin terms of abuse of authority) <strong>and</strong> exploitation in their work. Forexample, an overwhelming majority of workers from Nepal who migrateto Malaysia, the Gulf <strong>and</strong> India, work under exploitative workingconditions. United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM) hasstated that, in the case of women migrant workers from Nepal, exploitationis even more rampant, as very few protections are in place. Recruitmentagencies routinely deceive migrant workers as well. 8 With such a largeproblem, the “trafficking” category becomes somewhat redundant, <strong>and</strong>loses its value in terms of providing a few specific individuals with specialprotections.This is a question for us all to consider in our own national contexts. Insituations where the trafficking category could apply broadly, GAATW hasobserved that some governments <strong>and</strong> NGOs feel they must narrow thecategory because there is limited assistance to be offered – so they narrowit to include women in sex work only. This becomes problematic becausepeople in other forced or exploitative labour situations are ignored, whenthey very much need assistance, whether their situation is called“trafficking”, “forced labour”, “bonded labour”, etc. (see GAATW WorkingPaper <strong>Links</strong> with Labour 9 for more discussion on this).6On the other h<strong>and</strong>, categorising all or most migrants as “trafficked” canresult in quick <strong>and</strong> unhelpful protectionist responses. Migrant rights advocates<strong>and</strong> migrants themselves can be very frustrated when government or NGOresponses prevent people from moving, or “deport them for their owngood.” 10 GAATW has observed over the years that as more <strong>and</strong> more peopleare defined as trafficked, this restriction of movement <strong>and</strong>/or deportationin the name of anti-trafficking happens to more <strong>and</strong> more people.