Healthy Futures Report - LIME Network

Healthy Futures Report - LIME Network

Healthy Futures Report - LIME Network

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

HEALTHY FUTURESDefining best practice in the recruitment and retention ofIndigenous medical students

The Australian Indigenous Doctors’ AssociationYaga Bagaul Dungun

HEALTHY FUTURESDefining best practice in the recruitment and retention ofIndigenous medical studentsMs Deanne MinnieconProject CoordinatorDr Kelvin KongMedical OfficerAUSTRALIAN INDIGENOUS DOCTORS’ ASSOCIATION

<strong>Healthy</strong> <strong>Futures</strong>AIDA Working GroupDr Alex Brown, Ms Jane Magnus, Dr Helen Milroy, Dr Mark Wenitong, Dr Ngiare Brown, MrRomlie Mokak, Dr Tamara Mackean© Australian Indigenous Doctors’ AssociationFirst published in September 2005 by the Australian Indigenous Doctors’ Association.This work is copyright. It may be reproduced in whole or in part for study or training purposes,or by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community organisations subject to anacknowledgement of the source and not for commercial use or sale. Reproduction for otherpurposes of by other organisations requires the written permission of the copyright holder(s).ISBN 0–9758231–0–8Additional copies of this publication can be obtained from:The Australian Indigenous Doctors’ AssociationPO Box 3497 Manuka, ACT, 2603Tel: 61 + 2 62735013 Fax: 61+ 2 62735014 Email: aida@aida.org.auOriginal artwork: Mr Duncan SmithPhotography: Deanne Minniecon and Casey Eldridge. Thanks to Julie Tongs and staff atWinnunga Nimmityjah Aboriginal Health Services, ACT.Copy editing: ThemedaDesign: ThemedaPrinting: Elect Printingii

FOREWORDAssociate Professor Helen MilroyFirst I would like to acknowledge my people,the Palyku people, in particular mygrandmother and mother who taught meabout health and healing through my life.As current President of the AustralianIndigenous Doctors’ Association, I have greatpleasure in introducing this important work.As an Indigenous medical graduate myself, Ihave enjoyed seeing our Indigenous medicalstudents complete their studies and take uptheir place as colleagues in our health caresystems.Through researching this report, we have hadthe privilege of hearing many remarkablestories of Indigenous courage, strength andresolve. However, these stories have alsohighlighted that the strength of individuals,on their own, is not enough.Our children must have every opportunity toachieve their dreams, fulfil their potential andcontribute to the health and life outcomes forIndigenous people as well as the nation.This can be achieved through comprehensivepathways into medicine, culturally safe andaffirming student experiences, and recognitionof the unique and beneficial contributions tobe made as Indigenous medical practitioners.It will however, require a real and sustainedcommitment with observable actions at alllevels by governments, universities, medicalschools, and primary and secondary educationsystems.The Australian Indigenous Doctors’Association, as the sole body for Indigenousmedical graduates and students in the country,promotes the pursuit of leadership,partnership and scholarship in Indigenoushealth. We commit to all three dimensions,both within our Indigenous world and withour non-Indigenous peers and partners in therealisation of the Best Practice Framework.I look forward to the day when the numbersof Indigenous medical students and graduateshave equitable representation across the healthand education sectors. The implementation ofthis framework can go some way in achievingthis goal.On behalf of the Australian IndigenousDoctors’ Association, I would like to sincerelythank Deanne Minnecon, Project Officer,Jane Magnus, AIDA Secretariat, and DrKelvin Kong for their commitment andexcellent work in producing this report.Dr Kelvin KongI acknowledge and thank my family, mybeautiful wife, and the Worimi communityfor their support and belief in this project. Aspecial thanks to Deanne Minniecon who hasbeen instrumental in the project developmentand progression. I also wish to thank JaneMagnus who has dedicated a lot of her timeensuring the viability of the project. Withoutthe assistance of these people this projectwould not have been successful.This document has been the desire andpassion of many students and graduates for along time. We hope that key stakeholders (e.g.Department of Education, Science andTraining [DEST], Office for Aboriginal andTorres Strait Islander Health [OATSIH],Australian medical schools; and secondary,primary and other education systems), thehealth workforce and wider community willrise to these challenges and fulfil theirobligation not only to Indigenous Australia,but to Australian society as a whole.iii

<strong>Healthy</strong> <strong>Healthy</strong> <strong>Futures</strong> <strong>Futures</strong>I have always had an interest in health,probably as a result of being surrounded by illhealth during my upbringing in the Worimicommunity. As I grew older it became moreobvious that it was our community beingaffected and not that of our non-Indigenouscounterparts. I was unsure how one wouldever know the answers nor the avenues toattempt to address the striking healthinequalities.I can recall the very day that cemented myinterest in pursuing a medical career. I was inyear 8 and participated in a careers day atuniversity. Two of the then Indigenousstudents were talking about studying medicineand how, as an Indigenous person it was arealistic option. Prior to this, studying beyondyear 10 was something I had never considered.These two students, now very successfuldoctors, Dr Louis Peachey and Dr SandyEades, gave me the inspiration to follow intheir footsteps. As I have progressed to bewhere I am now, I have never forgotten myinspiration in the beginning, nor thecontinued support I have attained from AIDAand its membership. I am fortunate to besurrounded by a group of Indigenous overachievers.Working on this report was a way toextend my inspiration, to give back, to assistand to encourage others as I have been.iv

CONTENTSForeword ............................................................................................................................ iiiAbbreviations .................................................................................................................. viiiAcknowledgments ...........................................................................................................ixExecutive summary .......................................................................................................... xi1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 11.1 The Australian Indigenous Doctors’ Association ............................................. 11.2 The Best Practice Project .................................................................................... 22. METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................................ 32.1 Methods ............................................................................................................... 32.1.1 Literature review ........................................................................................ 32.1.2 Surveys ........................................................................................................ 32.1.3 Unstructured interviews ............................................................................ 42.1.4 National workshop .................................................................................... 42.2 Study limitations ................................................................................................... 53. LITERATURE REVIEW ....................................................................................................... 63.1 Indigenous education ........................................................................................ 63.1.1 The early years ........................................................................................... 63.1.2 Barriers to education ................................................................................ 63.1.3 Higher education ...................................................................................... 63.2 Indigenous health workforce ............................................................................. 83.2.1 National Strategic Framework for Aboriginal and TorresStrait Islander Health .......................................................................................... 83.2.2 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health WorkforceNational Strategic Framework.......................................................................... 83.4 Recruitment and retention of Indigenous medical students in Australia .... 93.4.1 Barriers for Indigenous medical students ............................................... 93.4.2 Recruitment and retention studies ....................................................... 10v

<strong>Healthy</strong> <strong>Futures</strong>3.5 Recruitment and retention of Indigenous medical studentsin comparative countries ....................................................................................... 123.5.1 New Zealand ........................................................................................... 123.5.2 United States of America ....................................................................... 143.5.3 Canada.................................................................................................... 163.6 Australian Indigenous doctor and medical student numbers .................... 174. FINDINGS ...................................................................................................................... 184.1 Indigenous doctors and why they pursue medicine .................................... 184.1.1 Indigenous medical student and doctor numbers ............................ 184.1.2 Reasons for pursuing and staying in medicine ................................... 194.2 Existing Indigenous recruitment and retention strategies in Australia ........ 194.3 Themes in relation to best practice ................................................................ 214.3.1 Personal contact and community engagement ............................... 224.3.2 School and university visits ..................................................................... 234.3.3. Indigenous health support units ........................................................... 244.3.4 Indigenous medical school staff ........................................................... 264.3.5 Mentoring ................................................................................................. 274.3.6 Indigenous content in medical curriculum ......................................... 284.3.7 Cultural safety ......................................................................................... 294.4 Other themes in relation to recruitment and retention ................................ 304.4.1 Promotion ................................................................................................. 304.5 Admissions .......................................................................................................... 324.5.1 Alternative entry schemes ..................................................................... 324.5.2 Quotas for Indigenous medical students ............................................. 334.5.3 GAMSAT and UMAT ................................................................................. 334.5.4 Identification............................................................................................ 354.6 Support ............................................................................................................... 354.6.1 Finances ................................................................................................... 354.6.2 Scholarships ............................................................................................. 364.6.3 Tutorial assistance ................................................................................... 374.6.4 Collegiate support .................................................................................. 384.6.5 Career progression and development ................................................ 394.6 <strong>LIME</strong> Connection statement of outcomes and intent .................................. 40vi

CONTENTS5. DISCUSSION ................................................................................................................. 415.1 Approaches in Australia and other comparative countries ....................... 415.1.1 Targets and affirmative action .............................................................. 415.2 Gaps and barriers in the current strategies and ways forward ................... 425.2.1 Promoting medical degrees to Indigenous people ........................... 435.2.2 Enabling pathways for Indigenous people into medicine ................ 455.2.3 Appropriately supporting Indigenous people in medicine ............... 465.3 Recruitment and retention of Indigenous medical students iseverybody’s business .............................................................................................. 475.4 Summary............................................................................................................. 506. FRAMEWORK ............................................................................................................... 516.1 Headline targets ................................................................................................ 516.2 Principles ............................................................................................................. 53ATTACHMENT A................................................................................................................ 55References ...................................................................................................................... 63Endnotes .......................................................................................................................... 68vii

<strong>Healthy</strong> <strong>Futures</strong>ABBREVIATIONSABSAEPAIDAAIHWAMAAMCAMSAMWACCDAMSCPMCCPMECDESTGAMSATHECINMEDISUITASKRAAustralian Bureau of StatisticsNational Aboriginal and TorresStrait Islander Education PolicyAustralian Indigenous DoctorsAssociationAustralian Institute of Healthand WelfareAustralian Medical AssociationAustralian Medical CouncilAboriginal Medical ServicesAustralian Medical WorkforceAdvisory CommitteeCommittee of Deans ofAustralian Medical SchoolsCommittee of Presidents ofMedical CollegesConfederation of PostgraduateMedical Education CommitteeDepartment of Education,Science and TrainingGraduate Australian MedicalSchool Admissions TestHigher Education ContributionSchemeIndians into MedicineIndigenous (student) supportunitIndigenous Tutorial AssistanceSchemeKey Result Area<strong>LIME</strong> Leaders in Indigenous MedicalEducationMAPAS Maori and Pacific IslandAdmissions SchemeNAHS National Aboriginal HealthStrategyNAIDOC National Aboriginal and IslanderDay Observance CommitteeNSFATSIH National Strategic Frameworkfor Aboriginal and Torres StraitIslander HealthNOMS Northern Ontario MedicalSchoolOATSIH Office for Aboriginal and TorresStrait Islander HealthUBC University of British ColumbiaUMAT Undergraduate Medicine andHealth Sciences Admission Testviii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSThe Australian Indigenous DoctorsAssociation wish to thank the manyAboriginal and Torres Strait Islander medicalstudents and graduates who participated inthis study, as well as the Medical Faculties andschools, and Indigenous support units andstaff for allowing us to visit and for sharinginformation with us so willingly and openly.We would also like to pay our respects to andacknowledge the Aboriginal and Torres StraitIslander community as well as the generalmedical community for their support andguidance throughout the life of the project.We want to give a special thanks to theCommittee of Deans of Australian MedicalSchools for their assistance and supportduring the project and for the opportunity towork collaboratively for the duration of thisproject. AIDA hopes to continue thisinvaluable working relationship in the future.Thank you also to Mr Duncan Smith forallowing us to use his artwork throughout thedocument.Finally, we wish to acknowledge and thank theAustralian Government Department of Healthand Ageing, Office for Aboriginal and TorresStrait Islander Health for providing fundingfor this critical project.Without the support from these groups, thisproject would not have been possible.* In this document, we use the term ‘Indigenous’ to refer to the Aboriginal and Torres StraitIslander People of Australia. The terms ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’,‘Indigenous’, ‘First Australian’ and ‘Indigenous Australian are used interchangeably.ix

<strong>Healthy</strong> <strong>Futures</strong>x

<strong>Healthy</strong> <strong>Futures</strong>●●mentoring;curriculum; and● cultural safety.The Best Practice Project findings support theevidence that there is a severe shortage ofIndigenous doctors in Australia and showthere has been no growth in Indigenousmedical student numbers since 2003.It is clear that Australian medical schools arenot recruiting enough Indigenous studentsinto medicine and retaining them. Accordingto the literature, prior educational and otherdisadvantages severely impact on Indigenousstudents’ opportunities to successfully applyfor medicine. However, the findings indicatethat some medical schools are significantlymore successful at recruiting and retainingIndigenous medical students, even given thesedisadvantages. Successful recruitment andretention approaches can also be found inother comparative countries such as NewZealand, the USA and Canada. 9It is apparent that many national, state andinstitutional policies and strategies said toassist Indigenous people have failed. This isevident in the fact that the gap in mortalityrates between Indigenous and non-IndigenousAustralians remains at 20 years while in othercomparative countries it has significantlyfallen. 10 As noted in the CDAMS IndigenousHealth Curriculum Framework ‘there is aconvincing case that the health and wellbeingof Indigenous people in Canada, the USA andNew Zealand is strengthened by having theirsovereignty recognised and having controlover their own health care service delivery.’ 11Australian governments and medical schoolsneed to seriously consider what theseobservations mean for the success ofIndigenous medical student recruitment andretention strategies. The Best Practice Projecttherefore provides Australian governments andmedical schools with a framework, includingtargets, principles and actions, that will assistin this process.Headline targetsBy 2010:· Australian medical schools will have established specific pathways into medicine forIndigenous Australians· CDAMS Indigenous Health Curriculum Framework will be fully implemented byAustralian medical schools· There will be 350 extra Indigenous students enrolled in medicine 12xiiPrinciple 1All Australian medical schools and principalstakeholders have a social responsibility toarticulate and implement their commitmentto improving Indigenous health andeducation; and mustPrinciple 2Make the recruitment and retention ofIndigenous medical students a priority for allstaff and students and show leadership to thewider university communityPrinciple 3Ensure cultural safety and value and engageIndigenous people in medical school businessPrinciple 4Adopt strategies, initiate and coordinatepartnerships that open pathways to medicinefrom early childhood through to vocationaltraining and specialty practicePrinciple 5Ensure all strategies for Indigenous medicalstudent recruitment and retention arecomprehensive, long term, sustainable, wellresourced, integrative and evaluated

1. INTRODUCTIONIt is well known that Indigenous people arethe most disadvantaged group in Australia.Overall, they have poorer physical and mentalhealth; are less likely to complete primary,secondary and tertiary education; and do nothave the same employment opportunities asnon-Indigenous Australians. They are alsodealing with the compounding impact ofmultigenerational grief, loss and traumarelated to colonisation, the stolen generation,racism and discrimination, and culturaldislocation on a daily basis. 13Indigenous Australians are also dying at amuch younger age than either non-IndigenousAustralians or Indigenous people in other firstworld countries. The life expectancy gapbetween Indigenous and non-IndigenousAustralians remains at twenty years. Incomparison, the life expectancy gap inCanada, New Zealand and the USA has fallento between five and seven years. 24For both state and national Australiangovernments, the question remains: why doIndigenous Australians continue to live insuch extreme comparative disadvantage withwidening disparities, despite governmentpolicies and strategies aimed at eliminatingsuch disadvantage? More importantly, whatcan we all, Indigenous and non-Indigenous,do about it?In relation to medicine, the positive effects ofIndigenous doctors for Indigenous people’sphysical, emotional and cultural wellbeinghave long been recognised by government andother Indigenous and non-Indigenousstakeholders. 15 Clearly, more Indigenousdoctors are needed. According to theAustralian Medical Association (AMA), 928Indigenous doctors need to be trainedimmediately to reach workforce levelsproportionate to that of non-Indigenousdoctors to population ratios. 16Current government and university policiesrelevant to Indigenous medical studentsinclude allocated places for Indigenousstudents, alternative entry options andIndigenous (student) support units (ISU). Yet,most Australian medical schools still struggleto recruit and retain Indigenous students, andallocated Indigenous medical student placesmay be filled by other students.To better understand this, the AustralianIndigenous Doctors’ Association (AIDA) weresupported by the Australian GovernmentDepartment of Health and Ageing throughthe Office of Aboriginal and Torres StraitIslander Health (OATSIH) to research andreport on best practice in the recruitment andretention of Indigenous medical students.This project has become known as the <strong>Healthy</strong><strong>Futures</strong> Best Practice Project.1.1 The Australian IndigenousDoctors’ AssociationThe Australian Indigenous Doctors’Association (AIDA) is the leadingorganisation for Indigenous medicalworkforce issues and through this projectconfirms its commitment to leadership andinnovation in this area.AIDA provides collegiate and professionaldevelopment support to Indigenous medicalgraduates and undergraduates. It strives todevelop and maintain strong workingpartnerships with Australian medical schools,medical colleges, and key health andeducation organisations.AIDA recognises the outcomes of this projectas critical work in Indigenous medicaleducation and to that end will work withpartners in ensuring the implementation ofthe framework.1

<strong>Healthy</strong> <strong>Futures</strong>1.2 The Best Practice ProjectThe aim of the Best Practice Project is to assistAustralian medical schools, governments andother stakeholders in their efforts to supportmore Indigenous Australians in commencingand completing medical degrees.Project objectives●●●●●●<strong>Report</strong> on current numbers of Aboriginaland Torres Strait Islander doctors andmedical students and identify factors thatencouraged them to pursue a career inmedicine.Identify, collate and report on existingrecruitment, retention and graduationstrategies at Medical Faculties throughoutAustralia and include an audit ofIndigenous support units within thefaculties and their existing initiatives.Where possible, this work will takeaccount of any other recent studiesundertaken in this area and will notduplicate results.Liaise and collaborate with Committee ofDeans of Australian Medical Schools(CDAMS) to produce information andrecommendations that complement thework of the CDAMS Indigenous HealthCurriculum Project.Develop guidelines for mentorship ofIndigenous students. This shall includeresearch on how other countries havesucceeded in recruiting and supportingIndigenous students to graduation andcompare experiences in New Zealand,Canada, the USA and other Pacificcountries.Organise a workshop to present anddiscuss the draft report of the project tokey stakeholders.Identify resources required to ensuremedical schools adopt recruitment/retention/graduation strategies andmentorship programs.Intended outcomes●●●●●●Development of recommendations onbest practice models for recruitment,retention and graduation of Indigenousstudents in medicine.Development of best practice models forsupport units within medical schools.Development of best practice models forcultural safety for Indigenous medicalstudents.Identification of appropriate models formentorship.Resourcing of models of best practice forrecruitment, retention and graduation;mentorship; cultural safety; and otherissues as identified.Identification of key stakeholders to workcollaboratively in implementing projectrecommendations.2

2. METHODOLOGYThe Best Practice Project draws on both quantitative and qualitative methodology:●●assessment of quantitative data was used as a basis for assessing gaps in current recruitmentand retention strategies and as a platform for setting targets; whilethe qualitative data provides a way of deriving meaning and the ‘lived experience’ ofIndigenous medical students in order to better understand the context within which thetargets and principles will ideally be achieved.2.1 MethodsThe methods used to gather and discussfindings relevant to the recruitment andretention of Indigenous medical students andthe project objectives and outcomes included:●●●●a review of the literature;development and dissemination ofsurveys to Australian medical schoolsthrough Indigenous medical studentsupport workers, Indigenous medicalgraduates, and Indigenous medicalstudents;unstructured interviews; andconvening of a national workshop.2.1.1 Literature reviewNational and international literature relevantto the recruitment and retention ofIndigenous medical students was reviewed.The literature review was conducted betweenJuly 2004 to January 2005. Material wassourced from MEDLINE and PROQUESTdatabases, a library search, governmentdocuments, internet searches and unpublishedreports. Search terms included: ‘recruitment’‘retention’, ‘support’, ‘Indigenous’,‘Aboriginal’, ‘Torres Strait Islander’, ‘Black’,‘medical student’, ‘Indigenous education’ and‘Indigenous health’.2.1.2 SurveysSurveys were developed by AIDA withreference to information identified during theliterature review. Questions targetedIndigenous medical students, graduates andmedical schools (see Attachment A forsurveys). They were distributed to 15accredited Australian medical schools, two ofwhich are privately funded. Thirty surveyswere distributed to Indigenous medicalstudents, and another 30 were distributed toIndigenous medical graduates. The AIDAmembership database was used to identifypotential student and graduate participants forthe surveys. Where possible, this was crossreferencedwith student and graduatedatabases from the Indigenous support unitsof medical schools across Australia. Fourteenof the 15 medical schools, 15 of the 30medical students and 17 of the 30 medicalgraduates completed and returned the surveys,representing 93%, 50% and 57%participation rates respectively.3

<strong>Healthy</strong> <strong>Futures</strong>2.1.3 Unstructured interviewsUnstructured interviews were conducted withthirteen of the fifteen Deans of Australianmedical schools. Major aims were to:●●introduce the project and surveys;encourage support and leadership inrelation to issues specific to recruitmentand retention of Indigenous students inmedical schools; and● discuss and invite involvement of theDeans at a national workshop.Discussions with some Deans also extended toissues relating to the recruitment andretention of Indigenous medical students andin particular promotional and supportingactivities, resources, Indigenous support units,and Indigenous staff.Unstructured interviews were also conductedwith Indigenous and non-Indigenousuniversity staff, and Indigenous medicalstudents and graduates. The main reason forthese interviews was to engage keystakeholders and current or previous studentsin exploring the key drivers and determinantsof successful pathways throughout medicalschool in a comfortable and non-threateningmanner. The interviews recorded informationbased on participant-driven narratives anddialogues outlining their own or witnessedexperience of medical training and the contextin which it was conducted. Major themesincluded discussion of challenges andsuccesses, support needs, gaps and barriers,views on medical schools, views onrecruitment and retention, and livedexperiences of being an Indigenous medicalstudent.All interviews were conducted by the seniorauthor of the project. All qualitative interviewdata was recorded by hand, expanded andtranscribed, and then analysed in order toidentify major themes.2.1.4 National workshopA national workshop—the Leaders In MedicalEducation (<strong>LIME</strong>) Connection—was held inPerth on 8–10 June 2005 and was co-hostedby CDAMS and AIDA. The aim of theworkshop was for CDAMS to present theIndigenous Health Curriculum Frameworkand AIDA to present the initial findings of theBest Practice Project in order to encouragediscussion and feedback from workshopparticipants. Key stakeholders in Indigenousmedical education and Indigenous medicalstudent recruitment and retention in Australiaand New Zealand also made presentations.Participants were encouraged to discuss andfeed back on Indigenous medical curriculaand recruitment and retention issues in‘dynamic sessions’ that were recorded and thenpresented back to the workshop as a whole.Through this process, initial outcomes wereidentified and agreed by all workshopparticipants. Attendees at the <strong>LIME</strong>Connection included:●●●●●●●●Deans of seven medical schools;medical and university recruitment,retention and development staff;Indigenous doctors, students and otherhealth professionals;representatives from the University ofOtago, New Zealand;representatives from two MedicalColleges;postgraduate Medical Councilrepresentative;Australian state and national governmentrepresentatives from OATSIH andDEST; andlocal community-controlled Aboriginalmedical services representatives.4

METHODOLOGYThe initial outcomes of the <strong>LIME</strong>Connection focused on implementation,resourcing, partnerships and capacity issues inrelation to Indigenous medical education andthe recruitment and retention of Indigenousmedical students. Final outcomes and intentsof the <strong>LIME</strong> Connection are included in theFindings section of this book (see p. 40).2.2 Study limitationsStudy limitations are related to difficultiesidentifying the target group, students who didnot complete their degree course andparticipation rates.Data on the number of Indigenous medicalstudents and graduates may be misrepresentedsince it was difficult to estimate the total studypopulation from which to draw participants:●●●●Indigenous people may choose not toidentify as Indigenous for a number ofreasons;students and graduates are a mobilepopulation;cross-referencing to the AIDA databaseonly identified AIDA members ratherthan the entire target group; andnot all state and territory medicalregistration authorities maintainAboriginal or Torres Strait Islanderidentifiers.Reasons why some of the target group chosenot to participate in this project include busyschedules and hesitancy to divulge experienceof difficulties in relation to social, financialand academic issues.Students who had withdrawn or did notcomplete their medical degree were notincluded. Unfortunately, few resources wereavailable for identifying this difficult-to-findtarget group. In essence, non-inclusion of thisgroup may well bias the reports findingstoward the experience of those who were ableto negotiate and complete their medicalstudies. Inclusion of the factors thatcontributed to non-completion is clearly animportant target for further exploration of thecontext of the recruitment, retention andgraduation of Indigenous medical students.5

<strong>Healthy</strong> <strong>Futures</strong>3. LITERATURE REVIEW3.1 Indigenous educationIndigenous students continue to be the mosteducationally disadvantaged student group inAustralia. 17 The 2003 Overcoming IndigenousDisadvantage Key Indicators <strong>Report</strong>, 18 indicatesthat:●●●●●national school participation rates forIndigenous five year olds in 2002 wasonly 10.1%;Indigenous primary school students havesignificantly lower literacy and numeracyachievement than non-Indigenousstudents;Indigenous secondary students are lesslikely to complete compulsory schoolingthan non-Indigenous students;poor health impacts on schoolattendance; andthere is a strong correlation between lowincome families and lower scores inlearning outcomes.3.1.1 The early yearsThe impact of educational disadvantage onstudents during the early years of schooling ismanifested in learning difficulties, constantexperience of failure, alienation from teachersand peers, dropping out of school anddifficulty attaining higher education andgaining employment. 19Ensuring that Indigenous children beginformal learning as early as possible, are lessabsent from school, and are safe, healthyand supported by their family andcommunity will go a long way to improvingeducational outcomes. 20Steering Committee of the OvercomingIndigenous Disadvantage <strong>Report</strong>3.1.2 Barriers to educationThe Queensland School Curriculum Council,2002 21 identified a number of barriersaffecting Indigenous student participation andengagement in education (see Table 1),including:●●●●●●isolation, alienation and marginalisation;language and cultural barriers;health and wellbeing;socioeconomic circumstances and accessto resources and public services;racism and prejudice; andemployment opportunities.3.1.3 Higher educationOnly 12.5% of the Indigenous populationaged 15 years and over have attained postsecondaryqualifications, compared to 33.5%of the non-Indigenous population. 22Indigenous people are also much more likelyto attend a technical or further educationalcollege, including TAFE colleges than auniversity. The types of courses they undertakeare also more likely to be enabling and nonawardcourses, rather than postgraduatecourses. Indigenous students also have aharder time completing their studies andattaining qualifications than non-Indigenousstudents. 236

LITERATURE REVIEWTable 1. Barriers affecting Indigenous student participation and engagement ineducation.Isolation, alienation and marginalisation●Influence of distance, socio-cultural and geographic isolation on Indigenous studentsparticipation in schoolLanguage and cultural barriers●●●●●●The interest and relevance of curriculum and test materials for Indigenous studentsUnderstanding of Indigenous cultures (including staff and students)Cultural identity and linguistic backgrounds of Indigenous students, their families andcommunitiesIncorporation and recognition of ways of knowing and learning styles of IndigenousstudentsAccessibility of information and ideas, to Indigenous people for whom standard AustralianEnglish is not their first languageCommunity decision-making processes.Health and wellbeing●●Influence of violence on students participation in schoolInfluence of health factors (particularly hearing impairment) on students’ participation inschoolSocioeconomic circumstances and access to resources and public services●●Appropriateness of resources for Indigenous studentsEquity of access to and availability of resourcesRacism and prejudice●●●●Inclusiveness and cultural appropriateness of assessment frameworks for IndigenousstudentsHow learning is valuedRacism and prejudice in schools towards Indigenous studentsInvolvement of community members, parents and carersEmployment opportunities●Influence of employment opportunities on Indigenous students’ participation in school7

<strong>Healthy</strong> <strong>Futures</strong>3.2 Indigenous health workforceThe Standing Committee on Aboriginal andTorres Strait Islander Health developed theAboriginal and Torres Strait Islander HealthWorkforce National Strategic Framework inMay 2002 to… transform and consolidate the workforcein Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanderhealth to achieve a competent healthworkforce with appropriate clinical,management, community development andcultural skills to address the health needs ofAboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoplessupported by appropriate training, supply,recruitment and retention strategies. 24Following this, the National Aboriginal andTorres Strait Islander Health Council preparedthe National Strategic Framework forAboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health(NSFATSIH) in July 2003 as a framework foraction by governments.3.2.1 National Strategic Framework forAboriginal and Torres Strait IslanderHealthThe goal of the NSFATSIH is:To ensure that Aboriginal and Torres StraitIslander peoples enjoy a healthy life equal tothat of the general population that isenriched by a strong living culture, dignityand justice. 25The framework identifies nine key result areas(KRA). KRA 3 (a competent healthworkforce) recognises that… a competent health workforce is integralto ensuring that the health system has thecapacity to address the health needs ofAboriginal and Torres Strait Islanderpeople. 26The objective of KRA 3 is:A competent health workforce withappropriate clinical, management,community development and cultural skillsto address the health needs of Aboriginaland Torres Strait Islander people supportedby appropriate training, supply, recruitmentand retention strategies. 27KRA action areas are based on theimplementation of the Aboriginal and TorresStrait Islander Health Workforce NationalStrategic Framework.3.2.2 Aboriginal and Torres StraitIslander Health Workforce NationalStrategic FrameworkThe Aboriginal and Torres Strait IslanderHealth Workforce National StrategicFramework is based on the nine principlesconsistent with the 1989 National AboriginalHealth Strategy (NAHS):●●●●●●●cultural respect;a holistic approach;health sector responsibility;community control of primary healthcare services;working together;localised decision making;promoting good health;● building the capacity of health servicesand communities.The framework identifies five objectives.Objectives 1 and 4 directly relate toAboriginal and Torres Strait Islander medicalworkforce issues:Objective 1: to increase the numbers ofAboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peopleworking across all the health professions;andObjective 4: to improve the effectiveness oftraining, recruitment and retentionmeasures targeting both non-IndigenousAustralian and Indigenous Australianhealth staff working within Aboriginalprimary health care. 288

LITERATURE REVIEW3.4 Recruitment and retention ofIndigenous medical students inAustraliaVery little literature has been published on therecruitment and retention of Indigenousmedical students in Australia. Informationthat is available, is mainly found in articlesand reports concerned with wider Indigenousand often mainstream medical, health,education and workforce issues or in-housepublications of individual universities.Gail Garvey from the University of Newcastlehas produced a number of papers onIndigenous medical student recruitment,retention and curriculum issues in Australia.Her work includes:●●●Garvey G, Brown N. Project of NationalSignificance Final <strong>Report</strong>: AboriginalHealth A Priority for Australian MedicalSchools. 1999a. 29Garvey G, Rolfe E, Pearson S. Agents forsocial change: the University of Newcastle’sRole in Graduating Australian AboriginalDoctors. 2000. 30Garvey G, Atkinson D. What can medicalschools contribute to improving Aboriginalhealth. 1999b. 31Garvey (1999a) notes in the Project ofNational Significance Final <strong>Report</strong>: AboriginalHealth A Priority for Australian Medical Schoolsthat...universities exist in partnership with avariety of organisations including schoolsand local communities that can worktowards reconciliation. The responsibility isfar reaching and is much more than simplygraduating competent and caring doctors.While medical schools cannot singlehandedlycompensate Australia’s racisthistory or for the inequitable representationin society of Australia’s ‘minority’ doctors,they can choose to act as agents for socialchange through a variety of academicmeans, including admissions policies andcurricula reform. 323.4.1 Barriers for Indigenous medicalstudentsIn a 2002 Rural Practice article on Indigenouspeople becoming doctors and the obstaclesfacing them, Garvey is quoted as saying that… Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanderpeople face many obstacles in obtainingsimilar educational outcomes as their non-Aboriginal counterparts … this isparticularly so for health programs,including medicine. 33In this article, Garvey also states that factorsthat may be obstacles to the recruitment andretention of Indigenous medical studentsinclude:●●●●●●●●●●unfamiliarity with the roles andresponsibilities of health professionals,partly as a result of the limited number ofIndigenous health professionals withincommunities;levels of academic achievement that areconsistently lower compared with thegeneral student population;insufficient information regarding entryin to medicine including universitycourses and alternative entry programs;acceptance by medical schoolcommunities for those who have beenaccepted under alternative entryprograms;impacts on family responsibilities ofmature age student usually;impacts on family and communityobligations and responsibilities fromleaving family and community to study;isolation within university and fromfamily and community;learning to adapt to academic andstructured language patterns of medicine;lack of recognition of Indigenous peopleand cultures within curricula;dealing with discrimination andstereotyping;9

<strong>Healthy</strong> <strong>Futures</strong>●●financial support; andpressure to go back and practice only inIndigenous communities or organisationsboth from their own community and thewider community.3.4.2 Recruitment and retention studiesVarious studies and publications have beenundertaken by universities, individuals andgovernment agencies on the recruitment andretention of Indigenous medical students.Newcastle UniversityA report on the characteristics of studentsentering Australian medical schools by theAustralian Medical Workforce AdvisoryCommittee (AMWAC) in 1997 34 brieflyconsidered the recruitment and retentionactivities currently being undertaken by anumber of Australian medical schools. Thecommittee identified Newcastle University ashaving the most comprehensive and effectiveapproach through its course promotionactivities, culturally appropriate admissionprocedures and Supportive learningenvironment (see Table 2).Indigenous students in QueenslandA 2000 Queensland study on the role oftertiary education in strengthening Indigenoushealth by Williams and Cadet-James 36 foundthat a number of factors influenceparticipation and retention outcomes forIndigenous students including that:●●●potential students are concerned thattheir level of education is insufficient toallow them to undertake or sustaintertiary study;family and community support may beforthcoming only if they are able toperceive benefits of the study for thestudents and the community and theeducation process; andthe support by fellow students bothduring and after completion of study.Table 2. Approach by Newcastle University to recruitment and retention of Indigenousstudents.Course promotion activities●●●●Promotion of courses by academic staff, Indigenous students and graduates at schoolsand to Indigenous communities and Indigenous community health organisationsAdvertising of courses nationally through relevant media, including Koori mail and radioprogramsProvision of career development days with Indigenous students and graduatesparticipatingDocumentation about admission procedures and the Indigenous Liaison Office in facultypromotion material and the University Admission Centre guideCulturally appropriate admission procedures●●●Processes that are consultative to ensure that students receive family and communitysupport as well as support from the local Indigenous communitiesBroadly defined eligibility criteria that takes into account prior disadvantageRigorous application of final selection criteria, conducted over three days and based on:oooa briefing session followed by the Undergraduate Medicine and Health SciencesAdmission Test (UMAT);a community-based interview; anda structured interview and assessment10Supportive learning environment● A learning environment that provides teaching and research about Indigenous healthissues. 35

LITERATURE REVIEWThe report recommended that:●●●●tertiary institutions consider developingcourses that can be structured to enablethe incremental development of students’skills.whenever possible, educational activitiesshould take place within the community;tertiary institutions adapt admissioncriteria and educational strategies toreflect educational opportunities, bothformal and informal, Indigenous andnon-Indigenous, available in students’communities; andteaching institutions foster thedevelopment and maintenance of thestudent community and facilitate itscontinuing function as a past students’support network. 37Recommendations from this study were basedon the conclusion that recruitment andretention must involve a range of activitiesaddressing the holistic needs of the student.No shame jobNo Shame Job, by Adams (1999) is an easy-toreadbooklet aimed at encouraging Indigenouspeople to pursue a career in health. 38 Itcontains stories and messages from studentsenrolled in health degrees.The objective for putting this booklettogether is to encourage other youngIndigenous people to choose a career inhealth to show that there are many ways toreach you goals and that there is plenty ofinformation, places to study and people togive you advice and direction. 39Kiarna Adams is an Indigenous medicalstudent at the Centre for Aboriginal Medicaland Dental Health at the University ofWestern Australia, a 2001 member of theNational Youth Roundtable and the AIDABoard 2004/05 Student Representative. NoShame Job demystifies the process of applyingto university and other tertiary institutions,addresses common questions and concernsraised by potential applicants and addressesissues such as:●●●●●career choices in health;ways to reach your goals;educational and study concerns;institutional expectations; andhousing and financial assistance.Aboriginal and Torres Strait IslanderEducation PolicyThe Australian Government Aboriginal andTorres Strait Islander Education Policy (AEP)plays a role in efforts to increase therecruitment and retention of Indigenousmedical students. 40 The higher educationinstitutions’ Indigenous Education Statementsstate that improving access for Indigenousstudents is imperative, and that… issues such as disadvantagedbackgrounds, remoteness, financialconstraints and alienation form theeducation sector need to be overcome toensure adequate access for Indigenousstudents. 41Institutions have devised varying programsand initiatives to improve access in theirrespective institution. Some examples ofprograms include:●●●●alternative entry programs;outreach programs;scholarships; andalternative delivery modes.11

<strong>Healthy</strong> <strong>Futures</strong>3.5 Recruitment and retention ofIndigenous medical students incomparative countriesA considerable amount of literature isavailable on the recruitment and retention ofIndigenous medical students in comparativecountries and only a summary of thesefindings are presented. The studies andpublications from New Zealand, the USA andCanada considered in this report include:●●●New Zealand: Maori Participation inTertiary Education, by Jefferies, 1999 42 ;Training Needs Analysis for Maori MedicalStudents by Robbins and Tamatea,2001 43 , Maori and Pacific AdmissionsScheme, Te Kupenga Hauora Maori andPacific Health Website, 2005 44 ; andliterature from the University ofAuckland, website including the Vision2020 Strategy.United States: Preparing the Workforce forthe Twenty First Century (Project 3000 by2000) by Ready, 1994 45 ; Indians intoMedicine (INMED) program fromUniversity of North Dakota, 2004 46 , and;literature from the American MedicalAssociation 47 and Indian Health Service 48 .Canada: Aboriginal Health Care CareersProgram, University of Alberta, 2005 49 ;Northern medical school prioritisesaboriginal health, by Crump, 2004 50 ; 5%of Enrolment spots should be filled byNatives, by Haley, 2001 51 , and; literaturefrom the University of British Columbia(UBC) 52 , and the Northern OntarioMedical School (NOMS) 53 .students made up 7.5% and 2.9% of overallmedical enrolments in 2004. Maori andPacific Island numbers have increasedsignificantly in recent years and it is estimatedthat the number of Maori and Pacific Islandmedical practitioners will increase by 18%and 35% respectively in by 2005. 55Maori Participation in Tertiary EducationA study on Maori participation in tertiaryeducation by Jefferies, 1999, 56 identifiedshort- and long-term solutions to the lack ofMaori doctors in New Zealand. Short-termstrategies include●●affirmative action programs;bridging and enabling; and● students loans.Long-term strategies include:● improving overall education outcomes;● changes to career delivery advice;● improving the home environment; and● influencing teachers’ expectations andattitudes.A study by Robbins and Tamatea, 2001, ontraining needs analysis for Maori medicalstudents showed that mentoring, peersupport, personal development, placementwithin Maori health providers, Maori healtheducation and collegiate support were themost important factors for the successfulcompletion of medicine by Maori medicalstudents.3.5.1 New ZealandNew Zealand studies highlight low retentionand success rates by Maori in tertiaryeducation and aim to identify solutions toovercome potential barriers. According to theliterature, Maori doctors made up 2.7% of themedical workforce in New Zealand in 2003and Pacific Island doctors made up 1.1% in2001. 54 Maori and Pacific Island medical12

LITERATURE REVIEWUniversity of Auckland Vision 20/20Vision 20/20 is a University of Aucklandstrategy which includes a goal that by the year2020, 10% of the Auckland Medical Schoolwill be Maori. This program has been inoperation since 1999 and aims to encourageMaori and Pacific Islander school leavers toenter in to the medical school and healthrelatedsciences. Graduates from this programreceive a Certificate in Health Sciences. Oncompletion of this course students are able toapply for medical school or other healthrelatedcourses. 57 To date almost all graduateshave been accepted in to medical and healthcourses at the University of Auckland. In2002, nine of the twenty-seven graduates hadbeen admitted to medicine. 58Maori and Pacific Island AdmissionsSchemeIn order to increase the number of Maori andPacific medical students a separate entrypathway is available within the University ofAuckland through the Maori and PacificIsland Admissions Scheme (MAPAS). Thisprogram was established in 1972 as anaffirmative action program and seeks toprovide a supportive environment wherestudents, their families and staff accept acommitment to academic achievement andcultural integrity. 59 Potential applicants arerequired to demonstrate a high level ofacademic achievement and an activeinvolvement within their communities.The program offers a number of opportunitiesto successful applicants, including:●●●●●additional tutorial assistance;mentoring support;cultural opportunities on campusincluding Pacific language development,involvement in Maori and Pacific healthissues, and links with cultural activitieson campus;the Maori and Pacific fresher camp;support in gaining a University ofAuckland Access Award;●support to access the student learningservice; and● support through shared experiences andopportunities for family members tomeet staff.Successful applicants to this program areexpected to:●●●●●●attend class and complete assignmentwork;seek help early;attend tutorials as required;learn to speak Maori or a language of thePacific;support and mentor other Maori andPacific students;act as role models as future health leadersand representatives for their community;● contribute to the development of theFaculty.The success of the program is identified by thedemand for more places. Early in the programonly three places were allocated each yearhowever evidence suggests this has increasedto nine in 1972, 12 in 1990 and 25 by 2003.Treaty of WaitangiBehind most strategies to increase Maoriparticipation in tertiary education is theTreaty of Waitangi. The University ofAuckland in their Missions, Goals and Strategies(2001) acknowledge and support theresponsibilities and obligations of the Treatyof Waitangi when setting strategic goals. 60They currently have in place a number ofstrategies to increase participation ineducation for both Maori and PacificIslanders. These strategies include:●●recognising that all members of theuniversity community are encompassedby the treaty with mutual rights andobligations;supporting and resourcing the Runanga;13

<strong>Healthy</strong> <strong>Futures</strong>●●●●●●●●●●●recognising that significant levels ofdisadvantage accrue to Maori within theeducation sector;increasing numbers and improvingsuccess rates of Maori students at bothundergraduate and postgraduate levels;addressing issues related to access,participation, performance andoutcomes;increasing the numbers and improvingthe qualifications of Maori academic andgeneral staff within specific recruitment,development and retention plans;acknowledging that Maori staff havecommunity obligations that call on theirtime and expertise and recognise theappropriate performance of these throughthe rewards systems of the university;identifying and supporting leading edgeMaori academic initiatives;developing quality academic structuresand innovative programs that supportMaori language, knowledge and culture,and initiating the wananga;increasing the levels of Maori staffparticipation in research and publicationincluding support for innovative researchsuch as Kaupapa Maori approaches;ensuring Maori participation in keyaspects of the management structures andinstitutional life of the university;identifying and supporting individualsfrom departments and faculties who willliaise with the Maori academiccommunity; anddeveloping national and internationalrelationships as appropriate witheducational and cultural institutions andindigenous academic groups. 613.5.2 United States of AmericaThe Centre of American Indian and MinorityHealth website states that of America’s morethan 800 000 practising physicians, only1175 were American Indian in 2005. 62However, overall racial and ethnic minoritygroup (including African American, Hispanicand American Indian) medical schoolmatriculation rates increased 36.3% between1990 and 1994 to 12.4 percent of the totalnumber of medical school matriculations,coinciding with Project 3000 by 2000 andother initiatives. 63Project 3000 by 2000Project 3000 by 2000 was a national ethnicmedical student campaign developed by theAmerican Medical Colleges. It aimed to raisethe number of ethnic students enteringmedical school to 3000 in the nation’s 126medical schools by the year 2000. 64 Theprogram targeted potential students fromminority ethnic groups in high schools,introduced science programs into poorlyequipped schools, and provided mentoringand counselling for university studentsconsidering medicine. However, the projectemphasised that although short-termenrichment programs could contributesignificantly to increased enrolments inmedical schools, … strong academic highschool curriculum and access to a good collegewas more important, since far too fewminority students had access to either. 65Since the commencement of the project, alarge number of medical schools have becomeinvolved in a variety of educationalpartnerships with local school systems,minority community-based organisations andundergraduate colleges. Although the finalproject was unsuccessful in reaching its 3000ethnic medical students by 2000, it wassuccessful in maintaining educationalpartnerships between academic medicalcentres, colleges, secondary schools, andcommunity groups. These partnerships werefound to be key in long-term strategies toincrease the applicant pool of minoritystudents ready to pursue a career in medicine.14

LITERATURE REVIEWDoctors Back to School ProjectThe American Medical Association DoctorsBack to School Project 66 sent ethnic minoritydoctors and students back into theircommunities to attract young minority peopleto medicine by acting as role models andraising awareness. Presentations wereconducted in conjunction with othercommunity activities and different age groupswere targeted including:●●●●kindergarten through to third grade;fourth through to sixth grade;seventh through to ninth grade; andtenth through to twelfth grade.Indians into MedicineThe Indians into Medicine 67 (INMED) is… an academic support program aidingAmerican Indian Students in their quest toserve the health care needs of our nativecommunities.The program offers comprehensive educationand support to American Indian students tohelp them prepare for health careers. Supportservices include academic and personalcounselling for students, assistance withfinancial aid application, and summerenrichment sessions from junior high throughto professional school levels. Over 100American Indian health students participate inthis program each year and another 100attend the INMED annual summerenrichment sessions at junior high, highschool and medical preparatory levels. Most ofthe participants excel in maths and science.The INMED program maintains closerelationships with the University of NorthDakota School of Medicine & HealthSciences, area tribes and several nationaleducation organisations. The American IndianBoard of Directors ensures the programrepresents the Indian populations. Thenumber of Indian students who participate inINMED increases each year and the scopeof the program’s activities are expanding.INMED is making an impact. As of 2005,the program had graduated 163 Indianmedical doctors. 68 A total of 317 Indianhealth professionals have also graduatedthrough the program.Indian Health ServiceOther initiatives developed in the USA havebeen implemented through the Indian HealthService to increase the number of AmericanIndian health professionals in the workforce.The Indian Health Service by law must giveabsolute preference to American Indian/Alaskan Natives when recruiting staff, wherethe applicant has met all qualificationrequirements. The Indian Health Service alsoprovides a number of scholarship programs toAmerican Indian/Alaskan Natives includingthe following.●●●The Health Professions PreparatoryScholarship Program provides financialassistance to students enrolled in coursesthat will prepare them for acceptance intohealth professions schools. Courses maybe either compensatory (to improvescience, mathematics, or other basic skillsand knowledge) or pre-professional (toqualify for admission into a healthprofessions program).The Health Professions Pre-graduateScholarship Program provides financialsupport to students enrolled in coursesleading to a bachelor degree in specificpre-professional areas (pre-medicine andpre-dentistry).The Health Professions ScholarshipProgram provides financial assistance tostudents enrolled in health professionsand allied health professions programs.The recipient incurs obligations andpayback requirements on acceptance ofthis scholarships funding. Priority isgiven to graduate students, and juniorand senior level students, unlessotherwise specified. 6915

<strong>Healthy</strong> <strong>Futures</strong>3.5.3 CanadaThe literature suggests there are approximately200 Canadian Aboriginal physicians, whoaccount for 0.3% of the 60 000 physicians inCanada overall. The evidence also suggeststhat most of these physicians are recentgraduates and that this may in part be due to anumber of university initiatives aimed atincreasing Canadian Aboriginal enrolments inmedicine. 70University of AlbertaThe Office of the Aboriginal Health CareCareers Program was instituted by theUniversity of Alberta Faculty of Medicine andDentistry in 1998. 71 The program assistsAboriginal students to gain admission andgraduate from the Faculty of Medicine andDentistry and other Professional HealthSciences Faculties. As of 2001, the Faculty hadgraduated 23 Aboriginal physicians, and morerecent figures suggest that graduations haverisen to 33. 72 The mandate of the program isto:●●recruit Aboriginal students into theFaculty of Medicine and Dentistry andthe other Professional Health SciencesFaculties in order to correct the underrepresentationof Aboriginal physiciansand other health professionals;provide academic, administrative andsocial support and referral to applicantsand students in the program; and● familiarise and sensitise faculty and non-Aboriginal students to Aboriginal healthissues including traditional medicine.The faculty has a national recruitment policyand has recruited Aboriginal students fromacross Canada. The Coordinator of theprogram and Aboriginal medical students andgraduates… present[s] information on the program atnational and regional career fairs,workshops, schools, universities andconferences. 73Recruitment posters featuring Aboriginalstudents are produced annually anddistributed to Aboriginal schools,organisations and interested individuals acrossCanada. 74Northern Ontario Medical SchoolsThe Northern Ontario Medical School(NOMS) 75 targets potential Aboriginalmedical students and exposes non-Aboriginalstudents to Aboriginal issues and communitiesas part of the academic and clinicalcurriculum from their first year of medicine. 76They have also used community forums toidentify five major recruitment and retentionthemes. These include:●●●●●the need for pathways to encourage andnurture Aboriginal peoples into andthrough medical school;the need for knowledge and respect ofAboriginal history, culture and traditions;knowledge and exposure to the resourcesand expertise already available inAboriginal communities;opportunities for collaboration andpartnership between Aboriginalcommunities; andan understanding of the challenges andspecific health priorities of Aboriginalcommunities.The school has already begun to implementthe recommendations, starting from theschool bylaws call for … a minimum of fiveAboriginal representatives on the 35 memberboard of directors. 77 To ensure success ofAboriginal students admitted to NOMS, themedical school is assessing current supportsystems. In addition, non-Aboriginal studentsare exposed to Aboriginal issues andcommunities as part of the academic andclinical curriculum for all first-year students. 7816

LITERATURE REVIEWUniversity of British ColumbiaThe University of British Columbia (UBC) 79allocated 5% of its 128 medical seats forAboriginal students in 2004 and havedeveloped a number of recruitment strategiesand initiatives. Hayley, (2003), reports on astudy conducted by a group of first-year andsecond-year medical students at UBC. 80 Thisstudy found a lack of consistency throughoutthe country in how medical schools developedpolicies and initiatives to recruit and supportAboriginal people. On completion of thestudy the group committed themselves toproviding support to other Aboriginal medicalstudents. The group also developed arecruitment program that encouragedAboriginal high school students to considerhealth care as a career, including:●●●●Aboriginal medical students visiting highschools and talking to Aboriginalstudents;developing posters highlighting the needfor Aboriginal physicians;facilitating a network for high schoolstudents to obtain information aboutapplying to study medicine;linking Aboriginal students withAboriginal medical students andphysicians, thereby providing supportprior to entering medical school; and● a proactive associate Deans of admissionspolicy committeeUBC will also implement a program thatprovides support to Aboriginal students andaddresses the concerns of both theAboriginal community and the medicalschool. The same academic standards applyto Aboriginal people as to other students.However they are only required to achieve50% of the standard criteria for admission.The other half relates to community service,involvement in health care, the approach tothe practice of medicine, letters of referenceand so on.A number of Canadian universities have alsoembedded Aboriginal perspectives into theircurricula. Funding has been made availablefor Aboriginal students, and the need forgreater collaboration with Aboriginalcommunities in the region of medicalschools has also been acknowledged. 813.6 Australian Indigenous doctorand medical student numbersAccording to the AIHW, 2003, there were 90Indigenous Australian doctors compared to48 119 registered doctors in Australia overallin 2001. 82 This indicates that Indigenousdoctors account for 0.18% of the medicalprofession, despite 2.4% of the Australianpopulation being Indigenous. 83DEST data indicates that 102 Indigenousstudents were enrolled in medicine in 2003.CDAMS data 84 indicates that 9233 domesticand international students are currentlyenrolled in medicine in Australia overall.These figures indicate that Indigenous medicalstudents still only make up 1.1% of themedical student population.The AMA commissioned Access Economics 85to undertake a study on the Indigenous healthworkforce in 2004. The Australian MedicalAssociation (AMA) 2004 Discussion PaperHealing Hands – Healing Hands: Aboriginaland Torres Strait Islander WorkforceRequirements,... the AMA believes that to improve thehealth of Aboriginal peoples and TorresStrait Islanders it is critical to increase theproportional representation of this groupemployed within the general healthworkforce. To increase the proportion ofAboriginal peoples and Torres StraitIslanders working as health professionals tonon-Indigenous levels 928 doctors ... need tobe trained.According to the AMA, to fill the gap in 10entry years, fifty Indigenous students wouldneed to enrol in medical schools acrossAustralia each year for the next four years andthen one hundred would need to enrol eachyear after that. This would mean that eachmedical school in Australia would need toenrol three Indigenous students each year forthe first four years and seven each year afterthat. 8617

<strong>Healthy</strong> <strong>Futures</strong>4. FINDINGS4.1 Indigenous doctors and whythey pursue medicine4.1.1 Indigenous medical student anddoctor numbersAccording to the findings of the Best PracticeProject, 102 Indigenous medical students wereenrolled in medicine in 2004/2005. Incomparison to DEST figures for 2003 thisindicates that overall Indigenous medicalstudent enrolment numbers did not increasebetween 2003 and 2004.Indigenous medical student enrolmentnumbers have remained at 1.1% of overallmedical student enrolments since 2003 (seeTable 3).The Best Practice Project findings found thatthere were 76 Indigenous doctors in 2004/2005 compared to 90 in 2003 identified bythe AIHW statistics. 88 However, only 28.5%of medical schools surveyed kept an updatedrecord of the number of Indigenous studentswho had graduated in previous years.Table 3. Comparison of Best Practice Project findings on Indigenous medical studentenrolments with data on overall medical student enrolments collected by CDAMS(2004). 87University Indigenous medical Medical students Proportion ofstudents overall Indigenous to(BPP 2004/05)* (CDAMS, 2004) non-Indigenousstudents (%)Bond University 0 n/a** n/aFlinders University 2 387 0.5Griffith University 1 n/a n/aJames Cook University 16 388 4.1Monash University 1 993 0.1Notre Dame University 0 n/a n/aThe University of Adelaide 12 809 1.5The University of NSW 10 1274 0.8The University of Newcastle 24 455 5.3The University of Queensland 6 1029 0.6The University of Sydney 7 935 0.7The University of Tasmania 2 479 0.4University of Melbourne 2 1533 0.1University of Western Australia 19 869 2.1Australian National University# 0 82 0.0Total 102 9233 1.1* Data based on voluntary identification. Numbers may have altered since the course of theproject.** CDAMS does not carry data on privately funded medical schools.# The Australian National University did not participate in the Best Practice Project survey.18

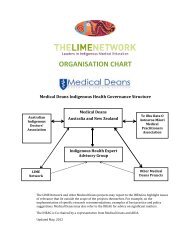

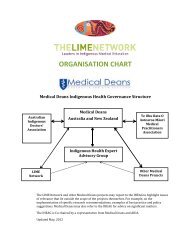

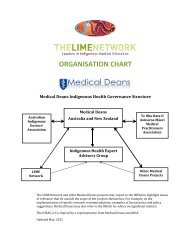

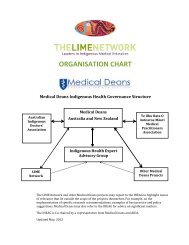

FINDINGS4.1.2 Reasons for pursuing and stayingin medicineIndigenous medical graduates chose to pursuea career in medicine for a range of reasons:●60% of medical graduates stated that itwas their desire to work in Indigenoushealth and with their community;● 86% attributed family members and rolemodels with providing encouragementand support to pursue a career inmedicine.Other factors influencing Indigenous medicalgraduate enrolments in medicine includedmarketing (e.g. seeing posters and articlesfeaturing Indigenous medical students anddoctors), university orientation camps and,collegiate support from Indigenous studentsalready enrolled.I wanted to help my people to dosomething personally to address theappalling state of Aboriginal health.Seeing a poster advertising Indigenouspeople studying medicine.Indigenous medical graduatesAll Indigenous students surveyed in thisproject stated they were determined to stay atmedical school and complete their studiesdespite experiencing many personal,academic, financial and other challenges.I am determined to finish and become adoctor and can’t wait to change the[poor situation of] our health.I have a burning desire to make adifference … I have come this far, I’m notgoing to give up now.I have strong personal commitment to mypeople, they are counting on me. I knowmy success in this will give them thegreatest satisfaction.Indigenous medical students4.2 Existing Indigenousrecruitment and retentionstrategies in AustraliaThe Best Practice Project found thatAustralian medical schools currently employ arange of recruitment and retention strategiesfor Indigenous students (see Figures 1 & 2, seenext page).19

<strong>Healthy</strong> <strong>Futures</strong>Figure 1. Recruitment strategies in Australian medical schools.AdvertisinginformationIndigenousheallthsupportunitIndigenousstaffPre-medical,enabling &bridgingprogramsOrientation/universityprogramsQuotasRecruitmentWHAT WORKS?Community/family linksAlternativeentryRecruitmentworkshopsMentorsSchool visitsRole modelsCareermarketsFigure 2. Retention strategies in Australian medical schools.ProfessionaldevelopmentIndigenousstaffIndigenoushealthsupport unitCollegiatesupportTutoringPracticalequipmentgrantsRetentionWHAT WORKS?Academic,clinicalsupportCommunitypartnershipsRole modelsIndigenouscontent incurriculumCulturalsafetyScholarship& financialassistanceMentors20

FINDINGSMany recruitment strategies draw onthemes similar to those used in retentionand vice versa. However, not all medicalschools employ all of the above strategiesand some do not employ any (see Table 4).Of the 14 medical schools surveyed by theBest Practice Project:●●●●57% have recruitment workshops;86% offer an alternative mode of entry;36% offer enabling or bridging programs;and36% have specific Indigenous health ormedical support units.4.3 Themes in relation to bestpracticeMedical schools with the greatest number ofIndigenous medical students identified acomprehensive approach including thefollowing elements:●●●●●locally based strategies;building relationships with potentialstudents, families and communities;Indigenous medical or health supportunits; andIndigenous staff; anduniversity and school visits.Table 4. Recruitment and retention strategies in use at different medical schools acrossAustralia.Medical schools MS1 MS2 MS3 MS4 MS5 MS6 MS7 MS8 MS9 MS10 MS11 MS12 MS13 MS14Recruitment workshops – – – – – – Enabling/ bridging – – – – – – – – – Identification – – – – – – – Alternative entry – – Subquotas – – – – – – – – Indigenous health units – – – – – – – – – Indigenous staff – – – – – – Scholarships – – – – – – – – – 21

<strong>Healthy</strong> <strong>Futures</strong>Mentoring, curricula and cultural safetywere also identified by staff, medicalstudents and graduates as integral to bestpractice. However, they said that not all ofthese elements were being implementedeffectively. The findings indicate that thethemes in relation to best practice are:●●●●●●●personal contact and communityengagement;university and school visits;Indigenous health support units;Indigenous staff;mentoring;curricula; andcultural safety.4.3.1 Personal contact and communityengagementThe importance of maintaining personalcontact, building trust and developingsupportive relationships, partnerships andnetworks was identified by all Indigenousstudent support workers as the mostimportant strategy for attracting Indigenousstudents to medicine and retaining them.… face to face contact visits as they givepersonal stories, detailed information andprogram and institution specific details.… personal contact, communityengagement … word of mouth.Indigenous student support workers on themost successful strategiesBest practice Indigenous health supportunits currently involve Indigenouscommunities in a number of ways,including:●●●●●●consulting, developing and implementingrecruitment and retention strategies withlocal community representatives;involving Indigenous communitymembers in the medical studentinterviews, selection processes andsupport;encouraging Indigenous communitymembers to regularly teach Indigenoushealth and cultural issues;providing regular opportunities forstudents to visit Indigenous communitiesand health services to talk withcommunity members and listen tocommunity issues;arranging clinical placements inAboriginal Medical Services (AMS); andmedical (or health school) staff buildingrelationships with local Indigenouscommunity members and families andregularly providing information onmedicine, higher education and medicalcourses.The community [members are] involvedwith the admissions interviews, delivery ofAboriginal Health curriculum, [and are]guest speakers etc. All medical studentsare offered to do electives with Aboriginalmedical services and communities inurban, rural and remote locations.Community research partners have beendeveloped [and there is] comprehensivecommunity engagement [and]representation on community boards.Indigenous student support worker at amedical school with a high number ofIndigenous students22

FINDINGSHowever, Indigenous medical graduates alsowarned against tokenistic and unsupportedcommunity involvement. This included notadequately preparing Indigenous communitymembers for the challenges of teaching intertiary institutions and concerns that contactwith communities was not comprehensive andappropriate.… you can’t just throw [communitymembers] in the deep end.… on paper it looks like they do a lot ofcommunity activities, but attendingNAIDOC week once a year is not enough.Indigenous medical graduatesOther issues raised by Indigenous studentsupport workers included frustration over lackof time to ‘get to the community’ due to otherwork pressures and concerns that theimportance of community involvement wasnot adequately valued by the medical schoolas a whole.Personal contact, building trust anddeveloping supportive relationships,partnerships and networks is the mostimportant strategy for attracting Indigenouspeople in to medicine and retaining them.4.3.2 School and university visitsSixty-seven percent of Indigenous studentsupport workers emphasised the importanceof engaging with primary and secondaryschool students regularly and in a number ofdifferent ways, depending on their age. Theseincluded:●●●●Indigenous medical students and doctorsvisiting schools and communities to talkabout medicine;Indigenous medical students and doctorsacting as role models and mentors foryounger children;primary and secondary students visitingmedical schools and universities fororientation days, and summer and healthcamps;arranging different recruitment activitiesand strategies for different age groups;and● regularly attending Croc festivals, Vibe 3on 3s and other local career festivals.Each of our strategies target differentpotential students. The year 8, 10 and 12camps are probably the best for schoolage. Word of mouth for older students.Media ads … [for] career options.Indigenous medical student supportworkerPlanned visits to the medical schools, touringthe school’s facilities and meeting faculty staffwere identified as significantly contributing tothe recruitment of Indigenous people tomedicine and/or other health fields.School contact, building relationships withprospective students, Indigenous specificcareer events and word of mouth.The building of relationships with both theprospective student and with theirfamilies is of paramount importance.Indigenous student support worker23