CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Eckesise <strong>representation</strong> in an international organisation. The Council <strong>and</strong> theCommission had concluded an inter-institutional agreement that regulated theexercise <strong>of</strong> voting rights within FAO. In the particular case, the agreement wasfound to be binding on the <strong>EU</strong> institutions. It is important to notice that the Courtdeduced the binding force <strong>of</strong> this agreement from the intention <strong>of</strong> the parties<strong>and</strong> from the duty <strong>of</strong> sincere cooperation. 108 It ruled that from the specific terms<strong>of</strong> the agreement that the parties had intended to make the agreement a bindingcommitment <strong>and</strong> that it was a specific expression <strong>and</strong> fulfilment <strong>of</strong> the duty<strong>of</strong> cooperation. For these reasons, the Court also enforced the arrangement.The duty <strong>of</strong> cooperation could even require the institutions to enter into a bindingarrangement on the exercise <strong>of</strong> voting rights in the Committee <strong>of</strong> Ministersor in the Parliamentary Assembly when it is dealing with issues related to the<strong>EU</strong>’s position under the Convention. 109 This might also explain the fear <strong>of</strong> non-<strong>EU</strong> Member States that the <strong>EU</strong> <strong>and</strong> its Member States might resort to blockvoting. As discussed above, the rules <strong>of</strong> the Committee <strong>of</strong> Ministers wereadopted to ensure the continuous effective functioning even if the MemberStates are under an <strong>EU</strong> law obligation to coordinate their votes.On a final note, it is important to stress that any comments about the specificscope <strong>of</strong> the duty <strong>of</strong> sincere cooperation <strong>of</strong> the Member States after the<strong>EU</strong>’s accession to the ECHR cannot be more than speculation. The Court’sinterpretation <strong>of</strong> the content <strong>of</strong> the duty <strong>of</strong> cooperation has very much beendependent on the context <strong>and</strong> circumstances <strong>of</strong> the individual case. 110 However,what is certain is that the <strong>EU</strong>’s accession to the ECHR is susceptible <strong>of</strong>entailing different <strong>and</strong> further-going duties for the Member States under <strong>EU</strong> lawthan the Member States’ own participation entails under international law.3.3. Implications for the Union <strong>and</strong> its Court <strong>of</strong> JusticeRather than making the <strong>EU</strong> more <strong>of</strong> a ‘human rights organization’ 111 comparableto the ECHR, accession will place the <strong>EU</strong> in a position similar to the otherContracting Parties, which are all states. Hence, the <strong>EU</strong> is accepted to join onequal footing with all state parties an international instrument as important inreach <strong>and</strong> influence as the Convention. This in itself is a success for the <strong>EU</strong>,confirming – as do many interactions with international organisations <strong>and</strong> thirdcountries – its particularity as an integration organisation.Pre-accession the <strong>EU</strong> is not itself directly bound by the Convention, eitherunder international law or under <strong>EU</strong> law. However, not only has the Court <strong>of</strong>Justice given great consideration to the Convention, but also the <strong>EU</strong> Treaties108 Commission v Council (FAO), supra note 106, paras. 49-50. See on the relevance onintention: T. Beukers, Law, Practice <strong>and</strong> Convention in the Constitution <strong>of</strong> the European Union,doctoral thesis, defended on 21 April 2011, at 212 <strong>and</strong> 242.109 With regard to the supervision <strong>of</strong> the execution <strong>of</strong> judgments <strong>of</strong> the ECtHR this might <strong>of</strong>course be less relevant.110 C. Hillion, ‘Mixity <strong>and</strong> Coherence in <strong>EU</strong> External Relations: The Significance <strong>of</strong> the “Duty<strong>of</strong> Cooperation”’, 2 CLEER Working Papers (2009), p. 8 et seq.111 A. Rosas, ‘Is the <strong>EU</strong> a Human Rights Organisation?’, 1 CLEER Working Papers (2011).120

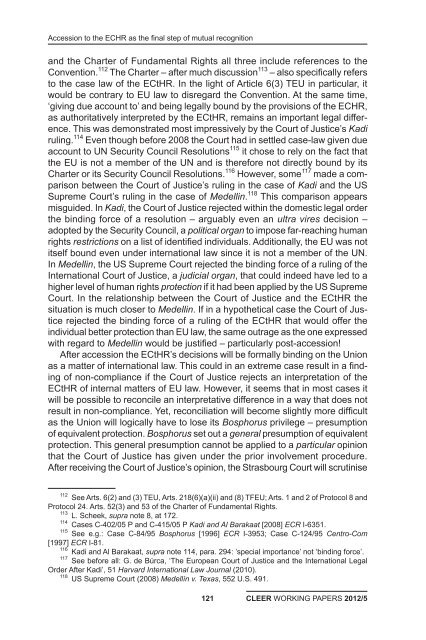

Accession to the ECHR as the final step <strong>of</strong> mutual recognition<strong>and</strong> the Charter <strong>of</strong> Fundamental Rights all three include references to theConvention. 112 The Charter – after much discussion 113 – also specifically refersto the case law <strong>of</strong> the ECtHR. In the light <strong>of</strong> Article 6(3) T<strong>EU</strong> in particular, itwould be contrary to <strong>EU</strong> law to disregard the Convention. At the same time,‘giving due account to’ <strong>and</strong> being legally bound by the provisions <strong>of</strong> the ECHR,as authoritatively interpreted by the ECtHR, remains an important legal difference.This was demonstrated most impressively by the Court <strong>of</strong> Justice’s Kadiruling. 114 Even though before 2008 the Court had in settled case-law given dueaccount to UN Security Council Resolutions 115 it chose to rely on the fact thatthe <strong>EU</strong> is not a member <strong>of</strong> the UN <strong>and</strong> is therefore not directly bound by itsCharter or its Security Council Resolutions. 116 However, some 117 made a comparisonbetween the Court <strong>of</strong> Justice’s ruling in the case <strong>of</strong> Kadi <strong>and</strong> the USSupreme Court’s ruling in the case <strong>of</strong> Medellin. 118 This comparison appearsmisguided. In Kadi, the Court <strong>of</strong> Justice rejected within the domestic legal orderthe binding force <strong>of</strong> a resolution – arguably even an ultra vires decision –adopted by the Security Council, a political organ to impose far-reaching humanrights restrictions on a list <strong>of</strong> identified individuals. Additionally, the <strong>EU</strong> was notitself bound even under international law since it is not a member <strong>of</strong> the UN.In Medellin, the US Supreme Court rejected the binding force <strong>of</strong> a ruling <strong>of</strong> theInternational Court <strong>of</strong> Justice, a judicial organ, that could indeed have led to ahigher level <strong>of</strong> human rights protection if it had been applied by the US SupremeCourt. In the relationship between the Court <strong>of</strong> Justice <strong>and</strong> the ECtHR thesituation is much closer to Medellin. If in a hypothetical case the Court <strong>of</strong> Justicerejected the binding force <strong>of</strong> a ruling <strong>of</strong> the ECtHR that would <strong>of</strong>fer theindividual better protection than <strong>EU</strong> law, the same outrage as the one expressedwith regard to Medellin would be justified – particularly post-accession!After accession the ECtHR’s decisions will be formally binding on the Unionas a matter <strong>of</strong> international law. This could in an extreme case result in a finding<strong>of</strong> non-compliance if the Court <strong>of</strong> Justice rejects an interpretation <strong>of</strong> theECtHR <strong>of</strong> internal matters <strong>of</strong> <strong>EU</strong> law. However, it seems that in most cases itwill be possible to reconcile an interpretative difference in a way that does notresult in non-compliance. Yet, reconciliation will become slightly more difficultas the Union will logically have to lose its Bosphorus privilege – presumption<strong>of</strong> equivalent protection. Bosphorus set out a general presumption <strong>of</strong> equivalentprotection. This general presumption cannot be applied to a particular opinionthat the Court <strong>of</strong> Justice has given under the prior involvement procedure.After receiving the Court <strong>of</strong> Justice’s opinion, the Strasbourg Court will scrutinise112 See Arts. 6(2) <strong>and</strong> (3) T<strong>EU</strong>, Arts. 218(6)(a)(ii) <strong>and</strong> (8) TF<strong>EU</strong>; Arts. 1 <strong>and</strong> 2 <strong>of</strong> Protocol 8 <strong>and</strong>Protocol 24. Arts. 52(3) <strong>and</strong> 53 <strong>of</strong> the Charter <strong>of</strong> Fundamental Rights.113 L. Scheek, supra note 8, at 172.114 Cases C-402/05 P <strong>and</strong> C-415/05 P Kadi <strong>and</strong> Al Barakaat [2008] ECR I-6351.115 See e.g.: Case C-84/95 Bosphorus [1996] ECR I-3953; Case C-124/95 Centro-Com[1997] ECR I-81.116 Kadi <strong>and</strong> Al Barakaat, supra note 114, para. 294: ’special importance’ not ‘binding force’.117 See before all: G. de Búrca, ‘The European Court <strong>of</strong> Justice <strong>and</strong> the International LegalOrder After Kadi’, 51 Harvard International Law Journal (2010).118 US Supreme Court (2008) Medellín v. Texas, 552 U.S. 491.121CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5

- Page 1:

Founded in 2008, the Centre for the

- Page 4 and 5:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Gosalbo

- Page 6 and 7:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Gosalbo

- Page 8 and 9:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Gosalbo

- Page 10 and 11:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Blockman

- Page 12 and 13:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Blockman

- Page 14 and 15:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Casolari

- Page 16 and 17:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Casolari

- Page 18 and 19:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Casolari

- Page 20 and 21:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Casolari

- Page 22 and 23:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Casolari

- Page 24 and 25:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Casolari

- Page 26 and 27:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Casolari

- Page 28 and 29:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Casolari

- Page 30 and 31:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Casolari

- Page 32 and 33:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Casolari

- Page 34 and 35:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Casolari

- Page 36 and 37:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Casolari

- Page 38 and 39:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Casolari

- Page 40 and 41:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Van Elsu

- Page 42 and 43:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Van Elsu

- Page 44 and 45:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Van Elsu

- Page 46 and 47:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Van Elsu

- Page 48 and 49:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Van Elsu

- Page 50 and 51:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Van Elsu

- Page 52 and 53:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Van Elsu

- Page 54 and 55:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Van Elsu

- Page 56 and 57:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Van Elsu

- Page 58 and 59:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Van Elsu

- Page 60 and 61:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Van Elsu

- Page 62 and 63:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Van Voor

- Page 64 and 65:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Van Voor

- Page 66 and 67:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Van Voor

- Page 68 and 69:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Van Voor

- Page 70 and 71:

CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Van Voor

- Page 72 and 73: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Van Voor

- Page 74 and 75: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Van Voor

- Page 76 and 77: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Van Voor

- Page 78 and 79: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Van Voor

- Page 80 and 81: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Van Voor

- Page 82 and 83: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Van Voor

- Page 84 and 85: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Van Voor

- Page 86 and 87: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5McArdle

- Page 88 and 89: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5McArdle

- Page 90 and 91: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5McArdle

- Page 92 and 93: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5McArdle

- Page 94 and 95: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5McArdle

- Page 96 and 97: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5McArdle

- Page 98 and 99: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5McArdle

- Page 100 and 101: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5McArdle

- Page 102 and 103: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5McArdle

- Page 104 and 105: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5McArdle

- Page 106 and 107: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Eckeswit

- Page 108 and 109: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Eckesdro

- Page 110 and 111: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Eckesto

- Page 112 and 113: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Eckesare

- Page 114 and 115: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5EckesEU

- Page 116 and 117: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Eckeswil

- Page 118 and 119: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5EckesPar

- Page 120 and 121: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Eckesthe

- Page 124 and 125: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Eckesand

- Page 126 and 127: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Eckesto

- Page 128 and 129: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Eckesarg

- Page 130 and 131: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Wouters,

- Page 132 and 133: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Wouters,

- Page 134 and 135: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Wouters,

- Page 136 and 137: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Wouters,

- Page 138 and 139: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Wouters,

- Page 140 and 141: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Wouters,

- Page 142 and 143: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Wouters,

- Page 144 and 145: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Wouters,

- Page 146: CLEER WORKING PAPERS 2012/5Wouters,