fiduciary duty issues in m&a transactions - Jackson Walker LLP

fiduciary duty issues in m&a transactions - Jackson Walker LLP

fiduciary duty issues in m&a transactions - Jackson Walker LLP

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

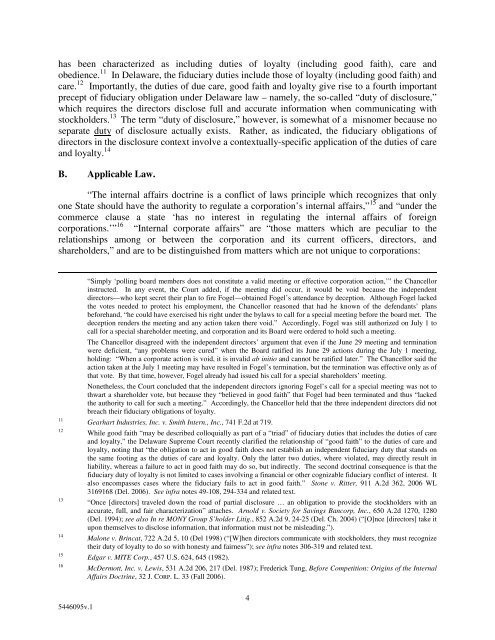

has been characterized as <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g duties of loyalty (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g good faith), care andobedience. 11 In Delaware, the <strong>fiduciary</strong> duties <strong>in</strong>clude those of loyalty (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g good faith) andcare. 12 Importantly, the duties of due care, good faith and loyalty give rise to a fourth importantprecept of <strong>fiduciary</strong> obligation under Delaware law – namely, the so-called “<strong>duty</strong> of disclosure,”which requires the directors disclose full and accurate <strong>in</strong>formation when communicat<strong>in</strong>g withstockholders. 13 The term “<strong>duty</strong> of disclosure,” however, is somewhat of a misnomer because noseparate <strong>duty</strong> of disclosure actually exists. Rather, as <strong>in</strong>dicated, the <strong>fiduciary</strong> obligations ofdirectors <strong>in</strong> the disclosure context <strong>in</strong>volve a contextually-specific application of the duties of careand loyalty. 14B. Applicable Law.“The <strong>in</strong>ternal affairs doctr<strong>in</strong>e is a conflict of laws pr<strong>in</strong>ciple which recognizes that onlyone State should have the authority to regulate a corporation’s <strong>in</strong>ternal affairs,” 15 and “under thecommerce clause a state ‘has no <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> regulat<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>ternal affairs of foreigncorporations.’” 16 “Internal corporate affairs” are “those matters which are peculiar to therelationships among or between the corporation and its current officers, directors, andshareholders,” and are to be dist<strong>in</strong>guished from matters which are not unique to corporations:111213141516“Simply ‘poll<strong>in</strong>g board members does not constitute a valid meet<strong>in</strong>g or effective corporation action,’” the Chancellor<strong>in</strong>structed. In any event, the Court added, if the meet<strong>in</strong>g did occur, it would be void because the <strong>in</strong>dependentdirectors—who kept secret their plan to fire Fogel—obta<strong>in</strong>ed Fogel’s attendance by deception. Although Fogel lackedthe votes needed to protect his employment, the Chancellor reasoned that had he known of the defendants’ plansbeforehand, “he could have exercised his right under the bylaws to call for a special meet<strong>in</strong>g before the board met. Thedeception renders the meet<strong>in</strong>g and any action taken there void.” Accord<strong>in</strong>gly, Fogel was still authorized on July 1 tocall for a special shareholder meet<strong>in</strong>g, and corporation and its Board were ordered to hold such a meet<strong>in</strong>g.The Chancellor disagreed with the <strong>in</strong>dependent directors’ argument that even if the June 29 meet<strong>in</strong>g and term<strong>in</strong>ationwere deficient, “any problems were cured” when the Board ratified its June 29 actions dur<strong>in</strong>g the July 1 meet<strong>in</strong>g,hold<strong>in</strong>g: “When a corporate action is void, it is <strong>in</strong>valid ab <strong>in</strong>itio and cannot be ratified later.” The Chancellor said theaction taken at the July 1 meet<strong>in</strong>g may have resulted <strong>in</strong> Fogel’s term<strong>in</strong>ation, but the term<strong>in</strong>ation was effective only as ofthat vote. By that time, however, Fogel already had issued his call for a special shareholders’ meet<strong>in</strong>g.Nonetheless, the Court concluded that the <strong>in</strong>dependent directors ignor<strong>in</strong>g Fogel’s call for a special meet<strong>in</strong>g was not tothwart a shareholder vote, but because they “believed <strong>in</strong> good faith” that Fogel had been term<strong>in</strong>ated and thus “lackedthe authority to call for such a meet<strong>in</strong>g.” Accord<strong>in</strong>gly, the Chancellor held that the three <strong>in</strong>dependent directors did notbreach their <strong>fiduciary</strong> obligations of loyalty.Gearhart Industries, Inc. v. Smith Intern., Inc., 741 F.2d at 719.While good faith “may be described colloquially as part of a “triad” of <strong>fiduciary</strong> duties that <strong>in</strong>cludes the duties of careand loyalty,” the Delaware Supreme Court recently clarified the relationship of “good faith” to the duties of care andloyalty, not<strong>in</strong>g that “the obligation to act <strong>in</strong> good faith does not establish an <strong>in</strong>dependent <strong>fiduciary</strong> <strong>duty</strong> that stands onthe same foot<strong>in</strong>g as the duties of care and loyalty. Only the latter two duties, where violated, may directly result <strong>in</strong>liability, whereas a failure to act <strong>in</strong> good faith may do so, but <strong>in</strong>directly. The second doctr<strong>in</strong>al consequence is that the<strong>fiduciary</strong> <strong>duty</strong> of loyalty is not limited to cases <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g a f<strong>in</strong>ancial or other cognizable <strong>fiduciary</strong> conflict of <strong>in</strong>terest. Italso encompasses cases where the <strong>fiduciary</strong> fails to act <strong>in</strong> good faith.” Stone v. Ritter, 911 A.2d 362, 2006 WL3169168 (Del. 2006). See <strong>in</strong>fra notes 49-108, 294-334 and related text.“Once [directors] traveled down the road of partial disclosure … an obligation to provide the stockholders with anaccurate, full, and fair characterization” attaches. Arnold v. Society for Sav<strong>in</strong>gs Bancorp, Inc., 650 A.2d 1270, 1280(Del. 1994); see also In re MONY Group S’holder Litig., 852 A.2d 9, 24-25 (Del. Ch. 2004) (“[O]nce [directors] take itupon themselves to disclose <strong>in</strong>formation, that <strong>in</strong>formation must not be mislead<strong>in</strong>g.”).Malone v. Br<strong>in</strong>cat, 722 A.2d 5, 10 (Del 1998) (“[W]hen directors communicate with stockholders, they must recognizetheir <strong>duty</strong> of loyalty to do so with honesty and fairness”); see <strong>in</strong>fra notes 306-319 and related text.Edgar v. MITE Corp., 457 U.S. 624, 645 (1982).McDermott, Inc. v. Lewis, 531 A.2d 206, 217 (Del. 1987); Frederick Tung, Before Competition: Orig<strong>in</strong>s of the InternalAffairs Doctr<strong>in</strong>e, 32 J. CORP. L. 33 (Fall 2006).5446095v.14