Smithsonian - Perishable Pundit

Smithsonian - Perishable Pundit

Smithsonian - Perishable Pundit

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

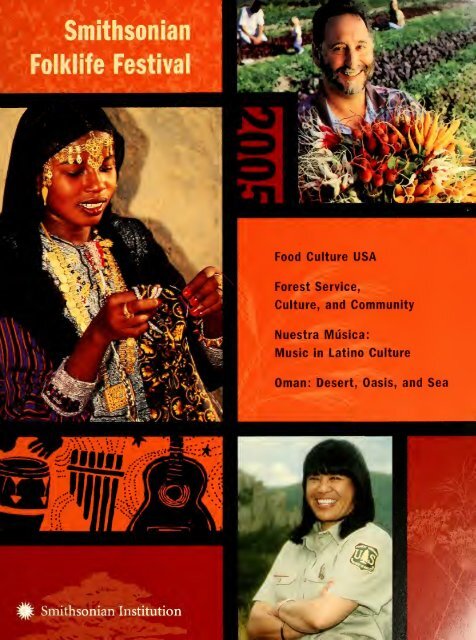

<strong>Smithsonian</strong>olklife Festival\Food Culture USA-. *...t-;Forest Service,Culture, and CommunityNuestra Música:Music inLatino CultureVfeL3?3Oman: Desert, Oasis, and Sea..-«** :"*

39th ANNUALSMITHSONIAN FOLKLIFE FESTIVALFood Culture USAForest Service, Culture, and CommunityNuestra Música: Music in Latino CultureOman: Desert, Oasis, and SeaJUNE 2 3 -July 4, 2005WASHINGTON, D.C.

The annual <strong>Smithsonian</strong> Folklite Festival bringstogether exemplary practitioners ot diverse traditions,both old and new, trom communities across theUnited States and around the world. The goal of theFestival is to strengthen and preserve these traditionsby presenting them on the National Mall,so that the tradition-bearers and the public canconnect with and learn trom one another, andunderstand cultural differences in a respectful way.<strong>Smithsonian</strong> InstitutionCenter tor Folklite and Cultural Heritage750 9th Street NWSuite 4100Washington, DC 20560-0053www.folklite.si.edu© 2005 by the <strong>Smithsonian</strong> InstitutionISSN [056-6805Editor: Carla BordenAssociate Editors: Frank Proschan, Peter SeitelAn Director: Denise ArnotProduction Manager: [oan ErdeskyGraphic Designer:ECrystyn MacGregor ConfairDesign Intern.Ann BlewazkaPrinting Stephenson Printing Inc., Alexandria, Virginia

SMITHSONIAN FOLKLIFE FESTIVALThe Festival is supported by federally appropriated funds; <strong>Smithsonian</strong> trust funds; contributions fromgovernments, businesses, foundations, and individuals; in-kind assistance; and food, recording, and craftsales. The Festival is co-sponsored by the National Park Service. General support for this year's programscomes from the Music Performance Fund, with in-kind support provided by Motorola, NEXTEL,WAMU 88. s FM.WashingtonPost.com, Pegasus Radio Corp., and Icom America. The 2005 <strong>Smithsonian</strong>Folklite Festival has been made possible through the generosity of the following donors.Lead SupportMinistries of Heritage and Culture, Tourism,Information, and Foreign Affairs of OmanUSDA Forest ServiceWhole Foods MarketFounding SupportWallace Genetic FoundationSilk SoyNational Forest FoundationNational Endowment for the ArtsHondaHorizon Organic DairyUnited States Department of AgricultureMajor SupportNEXTELChipotle Mexican GrillGuest Services. Inc.Honest TeaJean-Louis Palladin FoundationThe American Chestnut FoundationV.mns SpicesFarm AidJoyce FoundationIBMThe Rodale Institute<strong>Smithsonian</strong> Latino Initiatives FundUnivisionMajor In-kind SupportKitchenAidZola/Star Restaurant GroupCollaborative SupportWashington, DC Convention and Tourism CorporationCulinary Institute of AmericaMiddle East Institute/Washington, D.C.Ministry of External Relations of MexicoMarriott InternationalRadio BilingüePublic Authority for Crafts Industries of OmanSMITHSONIAN FOLKLIFE FESTIVAL

—CONTENTSThe Festival's Timely Appeal 7LAWRENCE M. SMALLCommerce for Culture: From the Festival andFolkways to <strong>Smithsonian</strong> Global Sound 9RICHARD KURINWelcome to the 200s <strong>Smithsonian</strong> Folkhte Festival 15DIANA PARKERFood Culture USA: Celebrating a Culinary Revolution 17JOAN NATHANForest Service, Culture, and Community 31TERESA HAUGH AND JAMES IDEUTSCHNuestra Música: Music in Latino Culture—Building Community 48DANIEL SHEEHYNuestra Música: Music inDANIEL SHEEHYLatino CultureConstruyendo comunidad 54Oman: Desert. Oasis, and Sea 61RICHARD KENNEDYCraft Traditions of the Desert, Oasis, and Sea 66MARCIA STEGATH DORR AND NEIL RICHARDSONAn Omani Folktale 74ASYAH AL-BUALYSMITHSONIAN FOLKLIFE FESTIVAL

Music and Dance in Oman 77OMAN CENTRE FOR TRADITIONAL MUSICKHALFAN AL-BARWANI, DIRECTORGeneral Festival Information 81Festival Schedule 84Evening Concerts 94Related Events 95Festival Participants 97Staff 121Sponsors and Special Thanks 124Site Map 130-131SMITHSONIAN FOLKLIFE FESTIVAL

—THE FESTIVAL'S TIMELY APPEALLAWRENCE M. SMALL, SECRETARY, SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTIONWelcometofour programsthe 2005 <strong>Smithsonian</strong> Folklife Festival! This year we feature[ 7IOman: Desert, Oasis, and Sea; Forest Service,Culture,and Community; Food Culture USA; and Nuestra Música: Music inLatino Culture. Now in its39th year, the Festival once again presentsa sample of the diverse cultural heritage of America and the world tolarge public audiences in an educational, respectful, and profoundly democratic way on theNational Mall of the United States. True to form, the Festival illustrates the living, vital aspectof cultural heritage and provides a forum for discussion on matters of contemporary concern.For the first time, the Festival features an Arab nation, Oman. Oman is at the edgeof the Arabian Peninsula, both geographically and historically situated between EastAfrica and the Indian Ocean. Trade routes, frankincense, silverwork, Islam, a strategiclocation, and oil have connected it to the cultures of the Middle East, Africa, Asia, theMediterranean region, and beyond. Contemporary Omanis live poised between a longand rich past and a future they are in the midst of defining. New roads, hospitals, schools,businesses, high-tech occupations, and opportunities for women are developing alongsidetraditionally valued religion, family life, artistry, and architecture. Omanis are wellaware of the challenges of safeguarding their cultural heritage inan era ot globalization.The Festival program provides awonderful illustration of the approaches they have takenand enables American visitors and Omanis to engage in open, two-way interchange.During the Festival, the U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service celebratesits 100th anniversary. Programs in previous years have illustrated the traditions of WhiteHouse workers and of <strong>Smithsonian</strong> workers. This Festival examines the occupationalculture of Forest Service rangers, smokejumpers, scientists, tree doctors, and manyothers devoted to the health and preservation of our nation's forests. They are joinedby artists and workers from communities that depend upon the forests for their livelihoodor sustenance. The Festival offers a wonderful opportunity tor an active discussionof the significance of our national forests and rangelands to the American people.Food Culture USA examines the evolution of our nation's palate over the pastgeneration. New produce, new foods, new cooking techniques, and even new culinarycommunities have developed as a result of immigrant groups taking their placein our society, the riseof organic agriculture, and the growing celebrity ot ethnic andregional chefs on a national stage. A diversity ot growers, food inspectors, gardeners,educators, home cooks and prominent chefs share their knowledge and creativity asthey demonstrate the continuity and innovation in America's culinary culture.SMITHSONIAN FOLKLIFE FESTIVAL

We also continue our program in Latino music this year with a series of evening concerts.Last year's program drew many Latinos Co the National Mall, helping the <strong>Smithsonian</strong> reachout to amajor segment of the American population. Audiences were thrilled by the performances,aswere the musicians who presented their own cultural expressions and thus helpededucate their fellow citizens of the nation and the world. <strong>Smithsonian</strong> Folkways releasedrecordings ot three of the groups, and one later went on to be nominated for a Grammyaward. This year, <strong>Smithsonian</strong> Folkways will hopefully continue that tradition with additionaltalented musicians from New York, Washington, D.C., Chicago, Puerto Rico, and Mexico.The Festival has provided an amazingly successful means of presenting living cultural traditionsand has been used as a model for other states and nations. It has also inspired other majornational celebrations. Last year, the Festival's producer— the Center for Folklife and CulturalHeritage—organized two major benchmark events. Tribute to ¡i Generation: The National Worldllin // Reunion drew more than 100.000 veterans and members of the "greatest generation" tothe Mall to celebrate the dedication of anew national memorial. Through discussions, performances,interviews, oral histories, and the posting of messages on bulletin boards, members ofthat generation shared their stories with some 200,000 younger Americans. It was a stirringand memorable occasion. Months later, the Center organized the Native Nations Procession andFirst Americans Festival tor the grand opening of the National Museum of the American IndianThis constituted perhaps the largest and most diverse gathering of Native people in history,ashunts from Alaska and Canada marched down the Mall along with Suyas from the Amazonrainforest, Cheyennes marched with Hawaiians, Navajos with Hopis, to claim their respectedplace inthe hemisphere's long cultural history. Over the course of the six-day celebration,some 000,000 attended concerts, artistic demonstrations, dances, and other activities andlearned a great deal about the living cultural heritage of America's first inhabitants.The Festival and the other national events inspired by ithelp represent the cultural traditionsot diverse peoples of this nation and the world to a broad public. The Festival is a uniqueexperience, both educational and inspiring, and one 111 which you, as a visitor, are wholeheartedlywelcome to participate. Enjoy it!SMITHSONIAN FOLKLIFE FESTIVAL

COMMERCE FOR CULTUREFrom the Festival and Folkways to <strong>Smithsonian</strong> Global SoundRICHARD KURIN, DIRECTOR,SMITHSONIAN CENTER FOR FOLKLIFE AND CULTURAL HERITAGEOneof the amis of the Festival isto promote the continuity of diversegrassroots, community-based traditions of Americans and people ofother countries. To do this, the Festival relies upon several methods[9]that demonstrate the value ot such cultural traditions. First, the<strong>Smithsonian</strong> invites members ot regional, ethnic, and occupationalcommunities to illustrate their artistry, skill, and knowledge at the Festival on theNational Mall. The symbolicvalue ot the setting and theinvitation by the nationalmuseum help convey theprestige accorded to the traditionand its practitioners.Second, we place Festivalparticipants in the positions ofteachers, demonstrators, andexemplars of the tradition.Providing astage for participantsto address their fellowcountrymen or citizens ot theworld m a dignified way onthe salient issues bearing ontheir cultural survival not onlyhelps visitors learn directlyabout the culture but alsoengenders aprofound respectfor it. Additionally, the officials,crowds, and publicity attendingthe Festival signal that theCraftspeople and artisans sell their goods at the Haitian Marketat the 2004 Festival, bringing much-needed income back home.prestige and respect are widespreadand important. Finally,commerce too plays a role. It Festival visitors buy food, music, crafts, and booksitshows that they value the culture produced by participants and members ottheir communities. Commerce has always been part ot the Festivaland part otour larger strategy to encourage the continuity of diverse cultural traditions.SMITHSONIAN FOLKLIFE FESTIVAL

Culture and CommerceCommerce has been intimately connected toculture for tens of thousands of years. Longbefore the invention of nations and money,to the importance of commerce in culturalproduction. As Food Culture USA illustrates, thephenomenon of commercial cultural exchangeisnot just a thing of the past. American culinaryand even before humans had settled invillagesculture has been immeasurably enriched byand cultivated crops, communities traded andimmigrants arriving over the last four decades.exchanged foodstuffs, stone tools, and valuableTheir presence has resulted innew foods, new10]minerals. Since then, no single people, country,or community has bv itself invented anew allof itsfusions, and new adaptations, as well as the growthof small businesses Family-owned restaurantsbecome centers of continuing cultural expréscultural products. Rather, cultures everywherehave depended upon an infusion of foods,sion, extending culinary traditions while atthematerial goods, songs and stones, inventionssame time helping promulgate new "tastes" forand ideas from others. So main1of the thingscustomers and neighbors. Similarly, Latino musicwe associate with particular cultures— tomatoeshas found vitality in contemporary America,with Italians, paper with Europeans, chiliswithnot only within its home community but alsoIndians, automobiles with fapanese, freedomwithin a larger market. That market has ensuredand democracy with Americans—areactu-new audiences and anew generation of musi-ally results of intercultural exchange. Much ofit has been of a commercial nature—whetherby barter or sale, borrowing or theft, donecians gaming broad recognition and attendanteconomic benefits. The cultural traditionsevident in and surrounding our forests are alsofairlyor through exploitation. Of course notbound up with economic relationships I oggers,all commercial exchange is tor the good.Sometimes commerce has led to the commodificationof things that should not be assignedmonetary or exchange value, eg .people, ashas been the case with slavery and human trafficking.Other items subject to commercialforesters, scientists, conservationists, artists, andothers are engaged in efforts to both exploit theforests commercially as well as preserve themCommerce is not only inherent in culturaltraditions featured at the Festival but also is partof its very structure. It has been so since theexi hinge—arms and drugs, for example—maybeginning. Ralph Rmzler, the Festival'sfoundinghave terrible, deleterious effects. Still, whilethere may be main' reasons to create andproduce goods and services— utility, tradition,prestige, and pleasure among them— exchangevalue certainly provides an incentive to do so.Commerce inand at the FestivalThe link between culture and commerceisamply illustrated at the Festival tins year.Many Omani traditions arise from an activeeconomy that connects the desert, oasis, andsea, and also connects C 'man to eastern Africa,India, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean.Frankincense, silver, jewelry, and the amazingboats— the dhows—that transported them, pointdirector, came to the <strong>Smithsonian</strong> from theNewport Folk Festival, where he encouragedmusicians and artisans to find new audiences andsources of income tor their art. Rmzler recognizedthat musicians had to make a living. Inn;oos he produced several albums for FolkwaysRecords and managed traditional music iconsDoc Watson and Dill Monroe. He thought thattheir skill and repertoire deserved attention andmerited commercial reward and appreciationFhe same impulse led him to team up withpotter N.mcN Sweezy and Scottish weaverNorman Kennedy to start Country Roads mCambridge, Massachusetts. This enterprise soldthe weavings, woodcarvings, baskets, ,\nd othertheSMITHSONIAN FOLKLIFE FESTIVAL

[ii]The food concession for the Mela at the 1985 Festival increased the popularity of Indian cuisine in theWashington, DC, metropolitan area and led to many restaurants, among them Bombay Bistro andIndique, which are directly operated by personnel associated with the 1985 program.crafts oftradition.il artisans and also aided manySouthern potteries, like Jugtown, to gam renewedand expanded commercial viability. As Festivaldirector, Rmzler would rent a truck, pick upcrafts from Appalachia, sell them on the Mall, andreturn money and respect to regional craftspeople.We continue this practice at the Festival,selling participants' crafts in our Marketplace ata very low mark-up. The idea is to encouragecraftsmanship by having audiences recognizeit as financially valuable. It is also why weDeveloping Commerce for CultureThe role of commerce m safeguarding diversecultural traditions is increasingly recognizedaround the world, particularly giventhe ascent ofwhat might be termed the"cultural economy."UNESCO, the UnitedNations Educational. Scientific, and CulturalOrganization, is currently developing a newinternational treaty on the topic tor considerationby its General Assembly in October 200s.The draft convention addresses the issue ofencourage musicians to selltheir recordings,cultural survival inthe face of globalizationcooks to sell their cookbooks, and so on. And itiswhy we select restaurateurs or caterers fromthe communities featured at the Festival tooperate food concessions and serve a culturallyappropriate menu. We are fostering exposureand knowledge for an important aspect ofculture, and also supporting the continuity ofpractice for those who carry these traditions.Itrecognizes the immense commercial value ofcultural products of varied types—from songsto books, from fashion motifs to films. Amongthe many positive provisions to encouragea diversity of cultural activity, it would alsoallow nations to make policies to restrict theln-flow of cultural goods and services thatmight jeopardize their own threatened orSMITHSONIAN FOLKLIFE FESTIVAL

endangered cultural traditions. The treaty offers.1 means oí gaming an exception from freeot cultural products between societies, orinvest the responsibility for cultural creation mtrade policies, thus increasing the commer-government agencies, itseems quite sensiblecialbenefits to homegrown cultural productsto marshal resources, invest inlocal cultural1-1while restricting cultural imports. For some,this particular provision is a legitimate way toprotect the diversity of national culture frommassive globalization. For others, it is a meansot limiting the tree flow of goods, services,and ideas through misguided protectionism.capacity building, encourage the developmentot cultural industries, and support amore robust, diversified world cultural market.Examples ot contemporary homegrowncultural industries abound. The Indian filmindustry, Bollywood, which at first imitatedHollywood, has developed itsown styles andThe motivation for the draft conventionis understandable, as local and regionalsocieties find themselves overrun \\ nliwidespread c ommercial success. Worldwide,Chinese restaurants, initiated and staffedproducts created and distributed by aglobal.by diasporic communities, tar outnumbercommercially produced, mass culture to theperceived detriment ot their own. To some, themultinational corporations are the bad guyswhose appetite tor greater market penetrationmust be stopped by national governments. Toothers, those governments are the problem,as a tree market, albeit one dominated bymultinational corporations, is more hkcb topromote freedom ot choice and a better life.Between restrictive protectionism andlaissez-faire tree market economics is perhapsathird way, more akin to the approach historicallyenacted at and through the Festival. Thislocates agency in people and communitieswho themselves have the power to act,

oMiiitbioni.indotal SoundL04.A 1 Slflti Uo

among others, to continue to develop the located in the museum world, the culturalWeb site's content. Shortly, other archives and heritage they represent is not something dead,institutions will be united to participate.or frozen, or stored away for the voyeuristicImportantly, the fact that artists benefit gaze ot tourists or the idiosyncratic interestfrom <strong>Smithsonian</strong> Global Sound is not lost ot scholars. Rather, we regard that heritage ason users. "I like the tact that artists get their something living, vital, and connected to thedue." offered one. This is an exciting moment identity and spirit ot contemporary peoples,wherein we tan help artists the world over all trying to make their way in a complicatedshare their know ledge and artistry with others, world today. Making that way takes mam things,contribute to ongoing cultural appreciationincluding money. To the extent that we can useand understanding, and secure needed income. commerce as a means tor people to continue toEven though the Festival, <strong>Smithsonian</strong>turn their experience into cultural expression.Folkways, and <strong>Smithsonian</strong> Global Sound are and benefit from it, the better ott we all will be.SMITHSONIAN FOLKLIFE FESTIVAL

1WELCOME TO THE 2005 FOLKLIFE FESTIVALDIANA PARKER, DIRECTOR, SMITHSONIAN FOLKLIFE FESTIVALhis summer marks the 39th time we have had the honor of bringing together people fromcommunities across the United States and around the world. The Festival has been calleda magical event, because when we bring together so many exemplary practitioners otcultural and occupational traditions, amazing things can happen. In order to make your|experience a memorable one, let me suggest some things we have learned over the years.Talk to the participants. The Festival is quite different from other <strong>Smithsonian</strong> exhibitions 111 thatthe artists are here for you to meet. Whether they are Omani embroiderers, bomba and plena musicians,smokejumpers or chefs, they are all accomplished artists. And you will probably not get a chance to learnfrom their like, face to face, ever again. They are the best in the world at what they do. and they haveagreed to come to share their knowledge with you. Don't let this opportunity pass you by.Read the signs and the program book. They can provide insights into the cultures you areexperiencing and the people you are meeting and help you ask questions. You will also rind schedulesand site maps that can help vou plan your visit. Finally, the program book listsand recordings that can expand your experience and knowledge.related activities, books,Pick up a family activities guide to help younger visitors participate in the Festival.Eachprogram has activities to help kids gam more from their Festival visit. A fun reward is available in each area toencourage young ones and help them take the experience home, where the learning can continue.Take your time. Listen and ask questions at the narrative stages. Join in a dance or a game. Take noteof a recipe from a cuisine that is new to you.Be aware of Festival visitors around you. Spaces near the front of music stages and food demonstrationareas have been reserved for the use of visitors in wheelchairs, and those reading sign-languageinterpreters. Please help us keep the spaces open for these visitors.Visit the Marketplace. The Festival is free, and the Marketplace helps support it as well as the workof traditional artists. Having traditional artists' work in your home can extend part ot the Festivalexperience year round. And be sure to visit the <strong>Smithsonian</strong> Global Sound tent too.Wear sunscreen and drink plenty of water. Washington summers can be brutal. Don't get soengrossed in the experience that you forget to take care of yourself. And itdn electrical storm arrives,leave the Mall immediately. Before 5:30 p.m., go into an adjacent museum; after that time, go downinto the Metro entrance. The Mall is a dangerous place in a lightning storm.Eat at Festival concessions. The food reflects the cultures presented at the Festival, and can expandyour culinary horizons. You may discover something you really love.Visit us in the off season. Go to our Web site, www.folklife.si.edu. Photographs, recipes, and activitiesfrom this year's Festival will be available. And please let us know what you think ot the Festival. We areconstantly striving to improve it, and your opinion matters to us. Thank youfor coming, and enjoy your visit.SMITHSONIAN FOLKLIFE FESTIVAL

FOOD CULTURE USACelebrating aCulinary RevolutionJOAN NATHAN[17]Inthe summer of 2001, when I was beginning to think about a FolklifeFestival program devoted to food, the <strong>Smithsonian</strong>'s National Museum oíAmerican History added Julia Child's kitchen to its exhibits, alongside someof the country's icons such as Thomas Edison's light bulb and the first Teddybear. At the opening reception for the exhibit, guests were served not theFrench dishes that Julia introduced to the United States, but a stunning menu ofAmerican food including seared bison filet with pepper relish and pappadam, purpleCherokee tomato tartlet with goat cheese and herbs, and a local organic sweettomato tart with basil and ncotta gelato.This meal was a patchwork of healthy,natural, spicy foods from different cultures that we Americans have embracedin the forty years since Julia published her firstbook. While, in one sense, Julia Child's kitchenrepresented the popular American introductionto French cooking, the reception menu showedthat its counters, appliances, and utensils had alsocome to symbolize a series of broader trends—anincreased interest in the craft of food in generaland in foods that could be considered American.The decades following the publication ot JuliaChild's Mastering the Art of French Cooking in 1961and the debut of her television show were a timeof momentous change in American tood. Duringthose years, the introduction of ethnic and regionaldishes to the American palate had opened ourChef Janos Wildergathers a bounty ofradishes at a farmnear his Tucsonrestaurant. Like anincreasing numberof American chefs,Wilder works closelywith growers toensure that he hasthe freshest, besttastingingredients.mouths and minds to a broader array ot tastes; agrassroots movement for sustainability had returnedmany to the world of fresh, seasonal produceknown to their ancestors; and chefs and cooks hadbecome explorers and teachers of diverse traditionsin food. This period has been called the AmericanFood Revolution. Whatever it is, this is the besttime in history for American food. For those whoThis article is adapted fromJoan Nathan'sforthcomingThe New American Cooking (Alfred A. Knopf).

Workers harvest artichokes at Ocean Mist Farms in California American agriculture depends on the skillsof migrant laborers, who continue to struggle for economic rights and adequate working conditionstake the time to cook at home or to dine outin ethnic and independent restaurants, the foodisthought out and delicious. We have artisanalc heese makers, local organic farmers, even moregreat grocery and ethnic stores than most of usever dreamed of. The world is at our fingertips,and it is a pleasure to cook. The very nature ofAmerica has become global, and this is reflectedin our food. Chef Daniel Boulud calls today'scooking "world" cuisine. He is not very far offT his revolution has come at a time whenmuch ot the news about food is less encouraging.During a visit to the Missouri countryside,1 stopped m at a mega-supermarketin a small town surrounded by farmland. Tomy surprise, m the midst of fieldsof freshstrawberries and fish streams overflowing withtrout, I found that everything in the marketwas plastic and processed. 1 thought aboutthe author Barbara Kingsolver's comment,"Many adults. I'm convinced, believethat food comes from grocery stores."In a similar vein, my son 1 )avid, whendiscussing the "American" book on whichthis Festival program is based, s.nd that 1 haveto include Cheese Whiz and McDonald's.No, Idon't. We know about the downside ofAmerican food today—the growing powerot fastfood chains and agribusiness, peoplenot eatmg together as a family, food thatisdenatured, whole processed microwavemeals, and the TV couch potato syndrome.1 have instead focused on the positive. Inpreparation tor my forthcoming book. The NewAmanan Cooking, and the Festival 1 have crisscrossedthis country from California to Alaskaand Hawai'i to New England and have enteredkitchens, farms, processing plants, and restaurants,seeking out the recipes and the peoplewho have made American food what it is today.1 have tried to show a fair selection ot what1 have seen, interviewing people in 40 statesthroughout our great country. 1 have brokenbread in the homes of new immigrants suchas Hmongs of Minnesota and Ecuadoreans inNew [ersey. 1 have noticed how, at Thanksgiving,the turkey Atid stuffings have been enhancedby the diverse flavors now available in thiscountry. Accompanying the very Americanturkey or very American Tofurky will be springrolls, stuffed grape leaves, or oysters, all holidayfoods from an assortment of foreign lands.That is American food today.SMITHSONIAN FOLKLIFE FESTIVAL

varieties of cilantro, peppers, yams, epazote, andhoney melon; and cramped aisles with chestnutand ginger honeys as well as brisket cut for stirfry,fajitas, and Korean hot pots. In Newark'sIron District, once home to Portuguese immigrants,the demographics are changing. DuringLent, I visited the 75-year-old Popular FishMarket. Brazilian immigrants had their pick oteel. clams, corvina, frozen sardines, lobsters, andbaccalhau (dried cod) piled in wooden crateswith a sharp chopper at the end. so that shopperscould cut off the fish tails. At the foodconcession at the University of California atSan Diego students can choose among Pekingduck, barbecued pork, and Mexican wraps.In New York one can see pedestrians noshingon vegetarian soul food, Chinese Mexicanfood, and Vietnamese and Puerto Rican bagels.Brighton Beach, Brooklyn, has turned into aLittle Russia with Cyrillic writing in shopsand restaurants. Chinatown in New York Cityisrapidly swallowing up what used to be LittleItaly. This kaleidoscope is a portrait of Americatoday—ever changing, spicier, and more diverse.[19]DIVERSITYMore than at any other time in our history,America's food has become a constantly changingblend of native and foreign ingredients and techniquescoupled with the most amazing ingredientsof all—American ingenuity and energy. TheCivil Rights Movement spurred Americans toexplore their rich African-American and NativeAmerican traditions. In 196$ a new ImmigrationAct lifted the quotas on immigration trom mainnon-European countries, contributing to anincrease in immigrants trom Latin American,African, and Asian countries. People tromIndia, Thailand, Afghanistan, and Lebanonbrought their culture in the way of food.This unprecedented wave ot immigrationmade the United States more multicultural thanever before. The figures tell the story: in 1970,of the 4 percent of foreign-born Americans,half came from European countries. Between1990 and 2000, over 6.5 million new immigrantscame to this country, resulting 111 32percent of the growth in the total U.S. populationover the same period. At 11percent, theproportion of immigrants in the United Statespopulation is the highest it has been in sevendecades. Of these, half are from Latin America,and almost all the rest are from countries noteven mentioned in the 1970 U.S. Census,such as Vietnam, Thailand. Afghanistan, andThis diversity has led to interesting juxtapositions.The Asian lettuce wraps I ate at alunch break with Cambodian refugee farmworkers in Massachusetts I've also seen atChill's and Cheesecake Factories. In Lajolla,California, Mexican workers eat Chinesefood while making Japanese furniture. HomeLebanon. As Calvin Trillin aptly wrote inthecooks frequently integrate dishes from diverseNewYorker, "Ihave to say that some serioustraditions into their menus, making personaleaters think of the Immigration Act of [965 astheir very own Emancipation Proclamation."This increased cultural and ethnic diversitycan be found across the country. An hour's drivemodifications and adding their own uniquepersonality to traditional dishes. One resultis that an Indian mango cheesecake is now asAmerican as Southern pecan pie. In the West,from that Missouri supermarket and its packaged,hummus isnow often made with black beans.processed goods, on St. Louis's loop alongside aStarbucks café and beer and pizza joints, wereEthiopian, Japanese, Lebanese, Persian, andThai restaurants. This street, in the heartland ofAmerica, could have been 111 Washington, D.C.;Berkeley, California; or Boston, Massachusetts.The De Kalb Market in Atlanta and the WestSide Market in Cleveland are tilled with endlessFor my own family, Imake pasta withpesto and string beans one day, Moroccanchicken with olives and lemon another, andMexican fajitas still another. My family's"ethnic" dishes might have less bite than theywould in the Mexican or Thai community,but our meals are a far cry from those ot mychildhood, when each day of the week wasFOOD CULTURE USA

—assigned aparticular dish—meat loaf, lamb chops, fish, roastchicken, spaghetti and meatballs, roast beef, and tuna casserole.Italian-American Jimmy Andruzzi, aNew York fireman whosurvived the World Trade Center tragedy, isthe one who cooksAmerica's foodhas becomeaconstantlychanging blendoí native andforeign ingredientsand techniquescoupledwith the mostamazing ingredientsoí allAmerican ingenuityand energy.all the meals in his firehouse at 13th Street and Fourth Avenue.Unlike his mother's totally Italian recipes, his are more Italian-American and just American. He cooks in between calls for firesand bakes his mother's meatballs rather than frying them. AnIndian woman married to a Korean man living in WashingtonHeights, New York, is a vegetarian. She makes a not-so-traditionalgrilled cheese sandwich with chickpeas, tomatoes, and theIndian spice combination, garam másala. Because there is notmuch cheese 111 India and that used is not so tasty, the "sandwich"as it existed in India contained no cheese. Since immigratingto America, she has added cheddar cheese to her recipe.These diverse traditions haw also changed the way Americanseat on the run. Quesadillas, dosas, and empanadas are eaten quicklyby busy people. With mass production, thev have become everydayfood m this country." These were foods that took time, individuallymade, and are ironically harder to prepare at home but easierin mass production," said Bob Rosenberg, a food consultant andformer CEO of Dunkin' Donuts. for example, California-bornGary MacGurn of the East Hampton Chutney Company spent 12years in .\n ashram in India before opening a small carryout in EastHampton, New York Gary's paper-thin white lentil and rice-baseddosas, which he loved while living 111 India, are tilled with such"cross-cultural- American" ingredientsasbarbecued chicken, arugula,roasted asparagus, ami teta cheeseAt the same time, traditions persist.Delicious authentic [amaican rumcakes, perfected bv awoman amiher daughter who have not changedthen[amaican blend tor Americantastes, have more "kick" than thosefrequently eaten inthis country.While many people bring traditionalrecipes out tor special occasions, thiswoman features her [amaican ruincake at her restaurant 111 Brooklyn.Sally Chow cooks asteak, string bean,and tofu stir-fry inMississippiSMITHSONIAN FOLKLIFE FESTIVAL

GRASSROOTS SUSTAINABILITYSupplying the creative cooks, urban markets,and rows of ethnic restaurants are an expandinggroup of innovative growers. Over the lastfour decades, farmers such as Ohio's Lee Jonesand his Chef's Garden have pioneered newmodelsfor agriculture. During that period,for cultural, culinary, environmental, health,and economic reasons many diets, environmentalists,and growers became advocates[21for locally grown, seasonal, sustainable, andorganic food. Today, these models ot agriculturehave entered the mainstream throughgrocery stores, farmers markets, and restaurants,altering the American food landscape.The backdrop for this shift in growingmethods is the consolidation ot American agriculturefrom family farms to a corporate, chemicallybased commodity model. During the middleof the 20th century, the American family farmfellinto steep decline under pressure from .\nexpanding national food market. Chemical fertilizers,mechanization, and hybrid seeds engineeredto resist disease and increase vields allowed farmersto produce more food. Highway transportationFour Season Farm in Harborside, Maine.We allknow that Americans did not alwayshave such broad tastes. As one person told me, "1was so glad that there was intermarriage into myNew England family, because the food had toget better." No longer can a sociologist write asPaul Fussell did in his 1983 book Class:A Cuidethrough the American Status System, "Spicy effectsmade iteasier to ship food great distances withinthe United States. Combined, these factors tiltedAmerican agriculture to a commodity productionmodel that favored uniformity, transportability,and high yield. This model developed atthe expense of crop diversity and small-scale localproduction—more common modes ot agriculturethroughout the 1 Nth and [9th centuries.Over time, the commodity model shiftedreturn near the bottom of the status ladder,control from farmer to processor. With alargewhere 'ethnic' items begin to appear: 1'ohshnumber of tanners producing the same cropssausage, hot pickles and the like. This istheacross the country, processors— companies thatmain reason the middle class abjures such tastes,believing them associated with low people,non-Anglo-Saxon foreigners, recent immigrantsand such riff-raff, who can almost always beidentified by their fondness tor unambiguousturn corn into corn chips, tor example—hadmain suppliers from which to choose. Asfarmers achieved higher and higher yields, pricessank. This spurred a continual consolidationof farms as family farms went bankrupt underand un-genteel flavors." Today, Americans likethe strainof higher equipment costs and fallingithot (in varying degrees), and Asian stir-tryvegetables and rice are as American as grilledsteak, baked potatoes, and corn on the cob.commodity prices. Larger corporate farmscould sustain greater levels of capital investment111 machinery and survive on high volume.FOOD CULTURE USA

I--IPot Pie Farm manager Elizabeth Beggins sells organicvegetables, garlic, onions, herbs, and cut flowers atthe St. Michaels FreshFarm Market in Maryland.Hmong farmers are thriving, selling theirfresh produce at the Minneapolis andSt Paul farmers markets.Critics argued that while these largecorporate farms raising single commoditiesmight have been good at supplying singlecrops to faraway producers, they underminedrural ways of life, environmental quality, andfood diversity. Over the course of the secondhalf of the 20th century, more and moreAmericans have agreed. They have becomeand other herbs. In Maryland, West Africantanners grow chilis. With the number ot Asianimmigrants rising sharply 111 Massachusetts, theUniversity ot Massachusetts^ extension servicehas w uiked with tanners to ensure that vegetablestraditional to Cambodian. Chinese, and Thaidiets are available through local fanners markets.1 he organic farming movement is anotherincreasingly interested in a more diverse foodtrend that has played amajor role. The rootssupply and are more engaged in questioningwhat is retened to as their food chain—thepath their food travels from farm to table.ot modern organic tanning are 111 a holisticview ot agriculture inspired by British agronomistAlbert Howard, whose An AgriculturalSeveral trends have supported areturn toTestament conceived ot soil as a system thatdiversity and sustainability.The wave of recentimmigrants from countries around the worldhas brought their food-growing traditions tothe United States. Small-scale growers havesought new models of agriculture in order toremain economically viable and to promoteneeded to be built over time. Nutritional andgood-tastmg food would come from healthysi>il I loward's ideas were popularized in theUnited States in the middle of the 20th centuryby J.I.Rodale and his son Robert Rodalethrough their magazines and organic gardeningthe crop diversity on which the diverse dietsguides. In the[960s, the counterculture readoutlined above depend. The increased diversityof American food can be seen in crops that areplanted inhome gardens and on farms. In San1 )iego, ( 'alifornia, Vietnamese gardens coverfront lawns with banana trees, lemonerass,Rodale and saw organic tanning as a way toorganize society in harmony with nature and111 rebellion against industrial capitalism.At the same time, the Peace Corps andthe declining cost ot travel abroad "ave manySMITHSONIAN FOLKLIFE FESTIVAL

Americans a window onto cultures and foodways in tarawaycountries, leading them to question the distant relationshipbetween themselves and the growing ot their food. Like JuliaChild, others had become fascinated with French cooking whenliving in Paris. While Julia strove to demystify academic Frenchcooking for an American audience, Montessori-teacher-turnedchefAlice Waters brought French provincial traditions of buyingfresh ingredients locally and sitting down for leisurely mealsback to the United States. On her return from France, whereshe spent a year traveling, she opened the northern Californiarestaurant Chez Panisse. It became the center ot a movementto serve only locally grown, seasonal, sustainable food.By featuring new ingredients such as baby artichokes andcultivated wild mushrooms such as portabellos and shiitakeson cooking shows, in cookbooks, and in restaurants, chefs havebrought them to the attention of the public. When peopletaste them, they want to know how they can cook them andwhere they can find them. This newdemand helps to support more farms.Today, Ocean Mist and PhillipsMushrooms, tor example, cateringto customers' requests, have offeredthese products to the retail market.At the same time, local craftproduction began to flourish as artisansreturned to traditional methodsand consumers became increasinglyToday Americancheese is beingmade in boutiquecheese-makingplaces all overthe country—onthe farms whereanimals are milkedby hand—insmall batchesand by traditionalmethods..23.enamored of the tastes that result.In France you get French cheese. InEngland you get English cheese. InHolland you get Dutch cheese. TodayAmerican cheese is being made inboutique cheese-making places allover the country—on the farms whereanimals are milked by hand— in smallbatches and by traditional methods.Similarly, with boutique oliveoil makers sprouting up all overCalifornia, Americans no longer have to go to Italy for estatebottledextra-virgin olive oil. Although we have always hadSpanish olive oil, now we have American olive oilfrom Italianolives raised in California. Pomegranates, plump and red. andmangoes, in so many guises, once brought in from abroad forethnic populations, are now being grown in California andFlorida. And artisanal chocolate maker John Scharffenbergerisgiving European chocolates a run for their money.Andy and Mateo Kehler,cheese makers in Greensboro,Vermont, have approximately1 50 head of cattle from whichthey make their highly soughtaftercheeses. Mateo traveledthrough England, France,and Spain learning to makecheese from cheese masters.FOOD CULTURE USA

ISustainable farmers such as Eliot Coleman are proving that locally grown food is viable in allclimates. Here, Coleman harvests lettuce at his Four Season Farm in Harborside, MaineThe host of companies specializing in craftand sustainable production keeps expanding. Steve)emos, founder oí Silk Soy, started out makingsoy milk at a local fanners market in Boulder,< ni. irado. Michael Cohen started peddling tempeliin 1974 by a 25-year-old hippie and sixtunecollege dropout named |ohn Mackev.who opened the Safer Way, then one ot 25health food stores m Austin, Texas. Today,while most ot those other 24 health foodstores are defunct, Sater W.iv has grown intofor Lite Lite, abrand now owned by ConAgra. Henthe largest chain ot grocerystores with anCohen and [erry Greenfield propelled then peaceand love ice cream to the mainstream. StonyfieldFarm yogurt, Annie's Homegrown pasta, and( alitornia's Earthbound Farms all sell throughnational chains. ( lone are the days of unappetizingmacrobiotics, brown nee, and totu. A wholeindustry has arisen making veggie burgers andmeatless sausage and salami, Tofurkys tor vegetarianThanksgh ing dinners, and "not dogs" and "phonybaloncv" all out or soy. While 25 years ago healthconsciousness was the domain of the counterculture,and vegetarianism and food coops were a signot pacifism, today they have become mainstream.An increasing number ot companies andretailers have pioneered nationwide markets.organic slant in the country. Whole Foods,with [65 stores coast to coast, are in mainplaees where there is rarely a hippie in sight.The retailer is now the leading outlet foragrowing number of national brands thatshare the store's commitment to health andsustainability. Whole Foods has also spurredother supermarkets to stock their shelveswith a growing number ot organic products.This combination ot environmental stewardship,flavor, and health is quietly buildingup around the country in schools, neighborhoods,and cities. As globalism increases inour kitchens and supermarkets, there iscountervailing trend of people who want toa1 he health-food mass movement was startedsee what can be produced intheir area ot thecountry. Most people realize, ot course, thatSMITHSONIAN FOLKLIFE FESTIVAL

eet from totally or partially grass-fed cows.And we are starting to ask questions aboutthe way these animals were raised. Do theycome from a family farm? Are they fedorganically? What does "natural" mean'coffee and chocolate need warmer climatesthan America otters, but an increasing numberof them are looking regionally rather thannationally for food to eat. Farmers markets,schools, and chefs have been at the forefrontof thismovement. Eliot Coleman, forBut the move to sustainable growing goesexample, a farmer in Maine, has come up withan enclosed, natural environment in whichfurther, bridging community, environmentalresponsibility, and taste. As grower Lee Joneshe can raise foods all year long. Followingsaid at arecent summit on the American foodhis lead, restaurants like Stone Barns inPocantico Hills, New York, are using thesystem. Many college food services, spurredrevolution, "The best farmers are looking ata way to go beyond chemical-free agriculture,they are looking at adding flavor andby Alice Waters and others, serve local applesatimproving the nutrient content. They arein the tall, labeling the varieties. Collegefood service administrators are increasinglygoing back to farming as it was five generationsago. It's truly a renaissance—there is nowvisiting farms and farmers so that they canachance tor small family farms to survive asmake connections. The American Universityin Washington, D.C., for example, not onlypart of thisnew relationship with chefs."serves local cheeses, but its administratorsvisit the farms from which the cheeses come.American consumers are demandingagreater variety of food, and they want toknow where their food comes from andhow itwas produced. Today we can getEliza Maclean raises heritage Ossibaw pigs outsideof Chapel Hill, North Carolina. She is just one of anincreasing number of growers who are helping topreserve the biodiversity of American food.FOOD AS EDUCATION:PASSING IT ONWhen my mother started to cook, she usedthe Joy of Cooking and the Settlement Cookbook,period. Since increased diversity, sustainability,and craft production have brought enthusiasmand energy to American food, there has been anexplosion of information about food. Accordingto the Library of Congress, in the past 30 yearsthere have been over 3,000 "American" cookbookspublished, more than in the 200 previousyears. At the same time, the number of cookingshows has ballooned. In the early19x0s, betweentelevision and the discovery of chefs innewspapersand cookbooks, something was happening.The firefighters at one of Chicago's tirehousesand shrimp fishermen in the bayous of Louisianawouldn't miss [uliaChild's show for anything,except maybe a tire. It was only after shebrought American chets onto PBS that the FoodNetwork took oft with aseries ot chefs whowould become household names—WolfgangPuck, Emeril Lagasse, and Paul Prudhonime.Now, Americans tune in, buy their cookbooks,and then seek out their restaurants. Chefs haveclearly become both major celebrities and majorinfluences in the way many Americans cook.FOOD CULTURE USA

"IThe numberof programsdesignedfor childrenhas swelledin the pastdecade alone.However, Americans are learning about food traditions in other ways.Founded in Italy in [986, Slow Food was organized in response to thesense that the industrial values of tasttood were overwhelming food traditionsaround the globe. As restaurants like McDonald's entered markets,they torced producers into their system of production and standards. Thisreduced biodiversity, promoted commodity agriculture, and underminedhospitality. Slow Food, in contrast, would document traditions and biodiversityand work toward protecting and supporting them. The InternationalSlow Food movement now has over 83,000 members organized intonational organizations and local "convivía" that celebrate the diversity andculture of their local foods. Slow Food USA has recently partnered with anumber ot other organizations—American Livestock Breeds Conservancy,Center tor Sustainable Environments at NorthernoArizona• University, Chefs Collaborative, Cultural Conservancy,INative Seeds/SEARCH, and Seed Savers Exchange— inaprogram called Renewing America's Food Traditionsew(RAFT). RAFT aims to document traditions, produce.and animal breeds, and then help their growers to developnew markets so that they become economically viable.Farmers markets and produce stands giveconsumers direct contact with tanners, allowing themto ask questions and learn about what is in season.Personal relationships help to create acommunitybond between growers and eatersThere are alsoopportunities tor people to become more directl)invoked 111the growing ot their tood. Local farmscalled CSAs (community supported agriculture)that are supported by subscribers who pay moneytor .1portion ot the farm's produce and who alsowork periodically planting, weeding, and harvestinghelp people learn about the source ot their tood.rhe number ot programs designed tor children hasswelled inthe past decade alone. Probably the bestknownprogram is Alice Waters's The Edible Schoolyard111 Berkeley, California. Begun 111 1994. the programisdesigned to bring the community and experientialethos of the locally grown-sustainable movementto middle school students. Seeing tood ascentral toStudents harvest kale atbuilding individual health, fulfilling socialrelationships, and communityThe Edible Schoolyard inBerkeley, California, and(opposite) the WashingtonYouth Garden at theU.S. National Arboretumin Washington, DC.lite, The Edible Schoolyard teaches children to plan a garden, preparesoil, plant, grow and harvest crops, cook, serve, and eat— in its phrasing,food "from seed to table.'' Students collaborate in decision-making on allaspects ot the garden. Working closely with the Center for Ecoliteracy,The Edible Schoolyard teachers have been on the forefront ot designinga curriculum that can place food at the center ot academic subjectssuch as math, reading, and history in order to "rethink school lunch."SMITHSONIAN FOLKLIFE FESTIVAL

a27Similarly, the Culinary Vegetable Institutein Huron, Ohio, has launched Veggie U toeducate food professionals and the generalpublic about vegetable growing and cooking.Recently, it has developed a curriculum forschools that will soon be m Texas systems.The Center for Ecoliteracy has developed adetailed "how-to" guide for school systemsto follow in creating their own programs.Spoons Across America, sponsored by theAmerican Institute of Food and Wine andthe |ames Beard Foundation, sponsors DaysofTaste in schools across the country. Localprograms also abound. In Washington, D.C.,Brainfood teaches children about life skillsthrough food activities after school and duringthe summer. The Washington Youth Gardengives children from the Washington, D.C.,public schools hands-on experience gardeningand then cooking their harvest. Programslike these are growing across the country.Then, of course, there is the timehonoredway of passing traditions on in familykitchens and on family farms. Hopefully, manyof these more formal programs remind cooksand growers to explore their own family traditionsand the foodways of those around them.This food revolution is about growing andcooking traditions and their adaptation to newcircumstances. It is about finding—amid a landscapedominated by pre-packaged goods—closer association with processes such as soilpreparation, harvesting, and cooking thatprevious generations took for granted. And itan awareness oí what a meal is, and how mealtimeis a time to slow down, to listen, and tosavor food. Perhaps most importantly, it is aboutsharing these things—or passing them on.This sharing and understanding taketime that today's busy schedules frequentlydon't allow. However, many are realizingthat the richness of shared experiencesinvolving food is too precious to give up.Thev think about the taste of afresh carrotpulled from a garden on a summer atternoonor a meal savored with family and friends.The food revolution that we celebratelooks both backward and forward: backwardto long-held community traditions ingrowing, marketing, cooking, and eating;forward to innovations for making thesetraditions sustainable and passing them on tofuture generations. It depends on nurturinga physical environment that supports diversity;sustaining the know ledge needed tocultivate that biodiversity; and passing ontraditions of preparing and eating. Together,these traditions are the foundation otmuch of our shared human experience.Everyone has to eat; why not cat together?isFOOD CULTURE USA

.hadSALAD GREENS WITH GOAT CHEESE, PEARS, AND WALNUTSThis recipe comes from Joan Nathan's The New American Cooking,to be published in October 2005 by Alfred A. Knopf.One of the most appealing recipes to come out of Alice Waters's Chez Panisse Restaurantin Berkeley, California, is a salad of tiny mache topped with goat cheese. How revolutionarythis salad seemed to Americans in the 1 970s! How normal today.[28]Alice got her cheese from Laura Chenel, a Sebastopol, California, native who was trying to liveoff the grid,raising goats for milk. The same year Chez Panisse really caught on, Laura went toFrance to learn how to make authentic goat cheese. When she came back, she practiced whatshe had learned, and it wasn't long before a friend tasted her cheese and introduced her toAlice. "All of a sudden the demand was so great," Laura told me, "that Ito borrow milkfrom others." Beginning with its introduction at Alice's restaurant at the right moment in 1979,the goat cheese produced at Laura Chenel's Chevre, Inc., became a signature ingredient in thenewly emerging California Cuisine. Today, artisanal cheese (made by hand in small batcheswith traditional methods) and farmstead cheese (made on the farm where it is milked) makeup one of the largest food movements in the United States. Chevre, Inc., has become synonymouswith American chévre, and Laura stilltends her beloved herd of 500 goats herself.Vi cup walnuts1Preheat the oven to 3504. Spread some of the goat1 teaspoon Dijon mustard2 tablespoons balsamic vinegarVt teaspoon sugar2 tablespoons walnut oil2 tablespoons canolaor vegetable oilSalt and freshly groundpepper to taste2 ripe Bosc pears5 ounces goat cheese6 slices French bread,cut in thin rounds8 cups small salad greensdegrees. Spread out thewalnuts in a small bakingpan and toast them in theoven untillightly browned,5 to 7 minutes. Take thewalnuts out of the oven,but leave the oven on.2. Mix the mustard with thevinegar and Vi teaspoon ofsugar in a large salad bowl.Slowly whisk in the walnutand canola or vegetableoil.Season with salt andpepper to taste. Set aside.3. Cut 1 pear into thinrounds. Peel and corethe second pear, slice itinhalf lengthwise, andcut into thin strips.cheese on the rounds ofFrench bread and top witha pear round. Then spreadsome more cheese on topof the pear. Bake in theoven a few minutes, untilthe cheese has melted.5. While the cheese is baking,add the salad greens tothe salad bowl with thethin pear slices and tossgently to mix. Divide thesalad among 6 to 8 plates.6. Place the hot pear-cheeserounds on top of thegreens, scattering thewalnuts around and serve.Yield: 6-8 servingsSMITHSONIAN FOLKLIFE FESTIVAL

. 2001SUGGESTED READINGBelasco, Warren. 1989. Appetitefor Change:How the Counterculture Took over the Food Industry,1966-1988. New York: Pantheon Books.Brenner, Leslie. 1999. American Appetite:TheComing ofAge of a Cuisine. New York: Avon Bard.Fitch, Noel Riley. 1997. Appetite for Life:Tlie Biography oj Julia Child. New York:Doubleday.Franey, Pierre. 1994. A Chef's Tale:A Memoir of Food, France, ami America.New York: Alfred A. Knopf.Gabaccia, Donna R. 1998.We Are Wliat WeEat: Ethnic Food and the Making oj Americans.Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.Halweil. Brian. 2004. Eat Here: ReclaimingHomegrown Pleasures in a GlobalSupermarket. New York: WW. Norton.Hess, John L., and Karen Hess. 1997. TheTasteof America. New York: Grossman Publishers.Schneider, Elizabeth. 1998. UncommonFruits & Vegetables:A CommonsenseGuide. New York: William Morrow.to. I egetables from AmaranthZucchini:The Essential Reference. NewYork: Morrow Cookbooks.Trager, James. 1995. The Food Chronology: A FoodLover's Compendium oj Events and Anecdotes fromPrehistory to the Present. New York: Henry Holt.JOAN N AT HAN, guest curator of Food CultureUSA, is the author ot numerous cookbooks,including Jewish Cooking in America, which wonboth the James Beard Award and the IACP/JuliaChild Cookbook of the Year Award. She has beeninvolved with the <strong>Smithsonian</strong> Folklife Festival asa presenter, participant, and researcher for over 25years. The Food Culture USA program is inspiredby the research she conducted for her cookbook,Tlie New American Cooking (Alfred A. Knopf,October 2005).All photographs courtesy ofJoan Nathanunless noted otherwise.[29]Lappé, Francis Moore. 1971. Diet for a SmallPlanet. New York: Ballantine Books.Oldenberg, Ray. 1989. The Great GoodPlace: Cafés, Coffee Shops, CommunityCenters, Beauty Parlors, General Stores, Bars,Hangouts, and How They Get Yon Throughthe Day. New York: Paragon House.\'PW^IPollan, Michael. 2001. The Botanyof Desire: A Plant's Eye I lew of theWorld.New York: Random House.Reardon.Joan. 1994. M.F.K. Fisher, JuliaChild, and Alice Waters: Celebrating the Pleasuresof thcTable. New York: Harmony Books.Schlosser, Eric. 2001. Fast Food Nation:The Dark Side of the Ail-American Meal.New York: Houehton Mifflin.FOOD CULTURE USA

w.A>wm:~

FOREST SERVICE, CULTURE,AND COMMUNITYTERESA HAUGH AND JAMES I.DEUTSCHMurray was in the fifth grade,WhenLezlieshe took a class outing to the nearby[3iGifíbrd Pinchot National Forest insouthwestern Washington State. "My bestfriend's father was a ranger, and he tookour class out into the forest and talked to us about the treesand everything that was a part of that environment. It reallystuck with me." Now an interpretive naturalist and director otthe Begich, Boggs Visitor Center at Portage Glacier m Alaska'sChugach National Forest, Murray has always cherished thatearly turning point in her life. "Every day I pinch nvyselt whenI get up," she explains. "I'm in the most beautiful place in theworld. I'vedone a lot of traveling, soIcan say that and really mean it."In many ways, Murray's story isnot unusual for those who live andwork in the forests, whether publicor private, m the United States.Growing up near a forest, or havingarelative who has worked outdoorswith natural resources, seems toinfluence one's choice of career path.Take, for example, Kirby Matthew,a fourth-generation Montanan whogrew up near the Trout Creek RangerStation in Montana's KootenaiNational Forest. His father workedas a logger and then with the ForestService, so it was natural tor Kirbyhimself to enter the Forest Service,where he has "a history." He nowworks for the Forest Service'sHistoric Building PreservationTeam in Missoula, Montana.Lezlie Murray leads a group ofvisitors on a trail to Rainbow Falls inAlaska's Tongass National Forest.

—3 3]OCCUPATIONAL CULTUREThe 2005 <strong>Smithsonian</strong> Folklife Festival programForest Service,Culture, and Community presentsoccupational traditions from the USDAForest Service, an organization celebratingits centennial, as well as other forest-dependenttraditions from the cultural communitiesit serves. Approximately too participantsare on the National Mall to share their skills,experiences, and traditions with membersof" the public; they include tree pathologists,wildlife biologists, landscape architects,historic horticulturalists, botanists, bird banders,archaeologists, environmental engineers, firefighters,smokejumpers. recreation specialists,backcountrv rangers, wooden vers, basketmakers, quilters, instrument makers, musicians,poets, storytellers, and camp cooks.Forest Service,Culture, and Community buildsupon previous Folklife Festival programs thathave examined occupational traditions, suchas American Trial Lawyers in [986, Wliite HouseWorkers in 1992, Working ¡11 the <strong>Smithsonian</strong> in[996, and Masters oj the Building Arts in 2001.Every occupational group including cowboys,factor) workers, farmers, firefighters, loggers,miners, oil workers, railroaders, security officers,even students and teachers—has itsowntraditions, which may have a variety of forms.One such form is the use oí a specializedvocabulary. For instance, city doctorsmay refer to malingering hospital patientsKennebec River in central Maine; pranks andjokes, which are often directed at the newestrookie; stones and personal remembrancesntwork incidents or characters; and a wideassortment ot customs and superstitions. Whattolklonsts at the <strong>Smithsonian</strong> try to understand,as they identify and ask questions aboutdifferent occupational traditions, are the skills,specialized knowledge, and codes of behaviorthat distinguish a particular occupationalgroup and meet its needs as a community.Another way ot looking at occupationalculture is to see it as a part ot a particularcompany, agency, or organization. As [amesQ. Wilson observes, "Every organization hasa culture, that is, a persistent, patterned wayof thinking about the central tasks of andhuman relationships within an organization.Culture is to an organization what personalityis to an individual. Like human culturegenerally, it is passed on from one generationto the next. It changes slowly, if at all."The tooth anniversary of the USDA ForestService in 2005 provides a splendid opportunityfor understanding and appreciating itsorganizational and occupational cultures.The occupational culture of theUSDA Fotest Service is representedby a diverse group of workers.as gomers,perhaps an acronym for "(let Outot My Emergency Room"; loggers intheNorthwest refer to blackberry ¡am as beatsignand hotcakes as saddle blankets; and academicsrefer to then' doctoral degree astheir union card,and books as tools of the trade, as if to suggestthat their ivory-tower realm has the same rigorand robust organization asthe factory floor.Inother cases, occupational traditions takethe form of specialized tools, gear, and clothingworn by members ot the occupational group;ballads and folk songs, such as "The [am onGerry's Rock," which tells oi a tragic accidentthatoccurred when floating logs jammed on theSMITHSONIAN FOLKLIFE FESTIVAL

FOREST SERVICE HISTORYThe origins of the Forest Service go back to themid- to late 19th century, when natural resourceswere in high demand throughout the country.Homesteaders wanted land, miners wantedminerals, and everyone wanted timber. Peopleoften took what they wanted with little regardfor the impact on the environment or for thefuture state of our natural resources. However, in1891, realizing the need tor greater control over3 3our forests, the U.S. Congress passed the ForestReserve Act, which authorized the President toestablish forested public lands in reserves thatwould be managed by the General Land Office(GLO) in the Department of the Interior.One of the first employees of the GLO wasGifford Pinchot (1865— 194.6), a Yale graduatewho not only had studied forestry inFranceand Germany but was also a personal friend ofPresident Theodore Roosevelt. (Pinchot was tobecome the namesake for the national forest that[960s.)Believing that professional foresters in thenaturalist Lezlie Murray visited in theDepartment of Agriculture and the forests theycared for should both be part of the same federalagency, Pinchot convinced Roosevelt in 1905 toapprove the transfer of the forest reserves fromthe Department of the Interior's GLO to theDepartment of Agriculture's Bureau of Forestry.As a result of this Transfer Act, 63 million acresof land and 500 employees moved to the USDA,and a corps of trained foresters was assignedthe work of conserving America's forests, withGifford Pinchot as the first Forest Service Chief.On July 1, [905, the Bureau of Forestry wasrenamed the Forest Service, because Pinchotbelieved the new title better reflected themission of the agency as being one of service.From 1905 to 1907, in spite of oppositionfrom local governments and the timberindustry, Pinchot and Roosevelt added millionsof acres to the forest reserves. Congress reactedin1907 by passing an amendment to theagricultural appropriations bill, taking awayfrom the President the power to create forestreserves and giving it instead to Congress. InAccording to Gifford Pinchot, first Chief of theForest Service,"Our responsibility to the Nation isto be more than careful stewards of the land; wemust be constant catalysts for positive change."that amendment, forest reserves were renamednational forests,leaving no doubt that forestswere meant to be used and not preserved.While most of the new national forestswere in the West, the passage of the Weeks Act111 1911 allowed for the acquisition of lands inthe East to protect the headwaters of navigablestreams. With that, the National Forest systembecame more environmentally diverse. BecausePinchot was convinced that the people who haddecision-making powers over forests should livenear the lands they managed, the Forest Serviceset up district offices 111 California, Colorado,Montana, New Mexico, Oregon, and Utah.Forest supervisors and rangers were given adegree of flexibility with their finances, and theybecame the voice of the Forest Service in thelocal communities. Later, districts were added torAlaska, Arkansas, Florida, and the Eastern states.Today, in 2005, the National Forest systemincludes isS national forests and 20 nationalgrasslands, and it encompasses 193 million acresof land m 42 states, the U.S. Virgin Islands, andPuerto Rico. This total acreage (roughly 300,000square miles) is larger than the entire state ofTexas, and comparable in size to the states ofNew York, Pennsylvania, Ohio. Indiana, Illinois,and Wisconsin combined. With nearly 38,000FOREST SERVICE, CULTURE, AND COMMUNITY

employees, the USDA Forest Serviceislarger than any other land-managementagency, including the Bureau ofLand Management (roughly 11,000employees), National Park Service(roughly 20,000 employees), and Fishand Wildlife Service (roughly 9,000employees), alloí which are part ofthe Department of the Interior.THE STATUS OF THE NATIONALFOREST SYSTEM TODAYFor the past100 years, the missionof the Forest Service has often beendescribed inPinchot's words as conservationfoinumbei 111the greatest good oj the greatestthe long run. However, theidea oí what is the greatest good canchange. Accordingly, the Forest Servicehas had to deal with many stronglyheld opinions about how nationalforests should be managed and used.Employing a concept of multiple use,and thus differentiating itself fromother land management agencies, theForest Service has tried over the yearsto accommodate awide variety ofuses for the forests and grasslands itmanages: timber, grazing, recreation,wildlife, and watershed protection.The relative value of extractingresources from national forests oftenchanges with current national events.For instance, after World War IF thedemand tor wood surged as AmericanGIs returning from the war needednew housing for their families andasthe United States was helping torebuild [apan.As a result, the ForestService was pressured to exchangeolder, slow -growing timber standstor younger, taster-growing trees.Golden Aspen trees in Idaho'sSawtooth National Forest.SMITHSONIAN FOLKLIFE FESTIVAL

[35]A forest ranger in 1910 poses while carrying hisheavy equipment load. After passing a writtenexamination, rangers had to endure hardships andperform labor under trying conditions.In1919 Helen Dowe was one of the earlyfire lookouts in Colorado's Pike NationalForest, scanning the landscape for smokeand signs of fire belowWood and other forest products are stillin demand, and the Forest Service mustsearch for the best ways to balance social,economic, and ecological demands.The forests have additional value ashomes to countless species of fish, birds,other wildlife, and plants, some ot which arethreatened or endangered. Forest Serviceemployees must look tor ways to protecthabitat while providing places for the publicto view plants and wildlife with minimal environmentalimpact. Fresh water from nationalforests and grasslands teeds into hundredsot municipal watersheds across the country,thereby providing clean drinking water tonearly do million people. And as the nationbecomes increasingly urban, people look totheir national forests as places tor fun andrecreation. They want somewhere they cancamp and hike, breathe fresh air, sit underORIGINAL FOREST RANGERSON THE JOBAs the multiple-use mission ot the agencyevolved, so did the Forest Service workforce.In the newly minted Forest Service ot 1905.allemployees were men. Rangers were custodiansof the land and proudly donned newuniforms with Forest Service shields, rodeon horses, carried guns, and wore hats. Theywere paid $60 per month and had to furnishtheir own equipment and pack animals.To be hired as .1 forest ranger, a man hadto have both scientific knowledge and practicalskills. He had to know about forestry, ranching.livestock, lumbering, mapping, and cabin building.In addition, he had to demonstrate that he couldsaddle and ride a horse, pack a mule, use a compass,and shoot a rifle. Some applicants were evenasked to cook a meal. In 1905, all Forest Servicethe shade ot trees, and listento birds sine.regulations could be contained 111 a single 142-FOREST SERVICE, CULTURE, AND COMMUNITY

I[3 6]page book, which could fit in the rangers shirtpocket. By contrast, todays Forest Service manualstillmany bookshelves and computer disks.In the early days, forest rangers and thenfamilies lived in isolated places. They wentwhere they were assigned, often on shortnotice. Their wives cooked, kept watch infirelookout towers, and took care of any visitorswho showed up at the doorstep (the ranger'shouse was usually the last one at the end of avery long road). Families learned to be selfsufficient,manage without electricity, and enjo)the adventure of living close to the land. Manychildren grew up believing this way of life wasthe norm, and learned to love and appreciate theoutdoors. The forest ranger by necessity becamepart of the community where he lived. Theranger developed working relationships withthe local ranchers, loggers, hunters, and fishermen.He was responsible for enforcing rules,issuing permits, and maintaining boundaries.The roles played by these early forest rangersforeshadowed the organizational culture andstructure of the agency we see today. In the 2 1stcentury, regional foresters, forest supervisors, anddistrict rangers are vences of authority in localcommunities, and are supported by a diverseworkforce ot men and women that includeswildlife biologists, fishery biologists, hydrologists,mineral experts, engineers, researchers, ecologies,forest planners, computer programmers,entomologists, firefighters, and other specialistsFORESTRY—GROWING TREESUnlike some other natural resources that areused once and then lost, forests are entitiesthat live and breathe, and can be renewed.Forest ecosystems can be maintained throughgood management, making the best use ofscientific research, such as ensuring naturalregeneration or planting seedlings to replacethe trees that have burned or have been cut.Professionalforesters use mam tools inmaintaining forest health. For example, theytake core samples and count annual ringsto help them understand how old a tree is,and to get a glimpse of the tree's life cycle.Foresters study how crowded trees are. howmuch undergrowth is present, and what kindof wildlife is dependent on the local habitat. AsSaul Irvin.a ranger with the florida DivisionotForestry, explains, "We plant trees, we marktrees, we control burn [intentionally settinga fire for prescribed purposes], we do everythingit takes to keep the forest growing."After a fire in 1936 in Montana's Lolo NationalForest, workers re-planted Ponderosa Pinetrees in an effort to rehabilitate the forest.CONTROLLING FIRESAt the beginning of the 20th century, manyprofessional foresters were trained 111 Europe,winch did not prepare them for the monumentaltiresthat used to sweep the NorthAmerican continent. Early settlers tendedto let large fires burn to clear the land forgrazing, but. as populations increased, peoplestarted looking at the threat of fire in adifferent way, and the control of tires becameamajor part of the Forest Service's work.After a million-acre tire in Washingtonand Oregon claimed 38 lives 111 1902. theForest Service became more systematic mits approach. It stationed people in lookouttowers, hired firefighters, and after World War Ihired Army pilots to spot firesfrom the air.he Civilian Conservation Corps was enlistedSMITHSONIAN FOLKLIFE FESTIVAL

. . [The[3 7]Fully suited, these smokejumpers in 1952 practice parachute-steeringmaneuvers while also strengthening their arm and shoulder muscles.during the 1930s to tight fires throughoutthe West. In1940, Rufus Robinson and EarlCooley became the world's first smokejumpers,parachuting into Idaho's Nez Perce NationalForest. Today, airplanes and helicopters drop notonly firefighters and equipment on tire linesbut also water and tire-retardant chemicals.Forest Service researchers are very proactivein studying fire and how it affects forestsm the long run. They consider whether it isbetter to stop firesfireor let them burn and howmight actually improve wildlife habitatand encourage the growth ot new trees. Fireresearchers manage torests to make them moreresilient to wildfire by removing underbrushand excess trees that literally add fuel to the tire.Sometimes they even use tire as a prescriptionto restore health to a forest that is overgrownor has the potential to burn out ot control.The history ot fire prevention intheForest Service is as old as the agency. Formany employees, their first job was keepinga 360 o vigil from a tire lookout tower, oftenspending their days m solitude. While lookoutsdo have contact with the outside world, theyhave had to find ways to fill their time. Theymight be found playing the guitar, writinga novel, or even riding an exercise bike.Donna Ashworth of Arizona has spent 26consecutive seasons on lookout tower duty.Ashworth doesn't feel alone when she ism the lookout tower, however, because she issittingconnected to others via radio. She describes herjob poetically:"! never get tired of it. It's alwaysbeauty. It's always the drama in the skyI live m the air. I can see 60, So. 100 miles."Ot course, lookouts are only onepart of the fire workforce. Others, suchas smokejumpers and firefighters, experiencefire from a very different perspective.As Kelly Esterbrook, a former smokejumperfrom Oregon, observes, "You definitelyhave to like to be physical. You just don'tget through the training program if youdon't enjov it. You have to like adventure.It's probably the best job I've ever had."Firefighters enjoy the challenge and thecamaraderie of the work. Linda Wadleigh. .1fire ecologist from Flagstaff, Arizona, beganas a forester but ended up as a firefighter.Wadleigh recalls, "Here I was a forestry major,and I decided I had a real love for fire. I wasraised a forester, but I was baptized in tire."She describes firefighting as compelling."Being called on a fire is one ot the strangestexperiences. .love ot tiretightmg] isa genetic disorder. . . . Once you smell thesmoke, it brines out the flaw in your DNA."FOREST SERVICE, CULTURE, AND COMMUNITY

ká.!i- .>!mKPA backpacker sets up camp at Buck Creek Pass in the Glacier Peak Wilderness of Washington's OkanoganNational Forest There are more than 450 trails here, and most are not completely snow free until mid-August.HIMANAGING RANGELANDSIn addition to protecting forests and rightingtires, the Forest Service also oversees themanagement ofrangelands and grasslands.Ranchers depend on Forest Service grazingpenults to provide forage for then cattleand livestock. The Forest Service works tomeet the needs of the ram hers, while at thesame time insuring that rangelands remainhealthy and available to future generations.Ranchers are not the only ones who enjo)what national grasslands provide. Visitorscome tor hiking, hiking, camping, hunting,fishing, and canoeing. The scenic beauty ofnational grasslands is an inspiration to photographers, birdwatchers, and Sunday drivers.Wildlife enthusiasts visit to catch a glimpseof vvhitetail deer, prairie dogs, prairiechickens, grouse, and butterflies.Managers have long realized that the wellbeingof forests and grasslands depends largelyon the health of the soil and the presenceof water. To grow plants and trees, they looktor vvavs to maintain healthy soil, match theright species to the soil, and prevent erosion.Especially in more arid areas of the West, theamount of rainfall is vital. Chuck Milner. arange specialist m Oklahoma's Black KettleRanger 1 )istrict, notes how "w hen it rams,everybody looks smart; when it doesn'tram, then you can't do anything right."SMITHSONIAN FOLKLIFE FESTIVAL