AJL magazine - Asian Jewish Life

AJL magazine - Asian Jewish Life

AJL magazine - Asian Jewish Life

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

ASIAN JEWISH LIFEA JOURNAL OF SPIRIT, SOCIETY AND CULTURE4Letter from the Editor 3Manila MemoriesHistory of Jews in the Philippinesby Bonnie M. Harris 4Best of <strong>AJL</strong>Feeding the World with <strong>Jewish</strong> WisdomA look at American <strong>Jewish</strong> World Serviceby Erica Lyons 8A Mementoby Sophie Judah 128A Musical Journey to Andhra PradeshUnderstanding the Bnei Ephraimby Irene Orleansky 15Five Star RefugeA Week at The Penby Erica Lyons 20Bene Israel HalwaSweet and simpleby Yardena Ben-Israel 2612Not Lost in TranslationA Torah scholar goes to Chinaby Gedaliah Gurfein 29Biblical Influences in Chinese Literatureby Tiberiu Weisz 33Interview with Hong Kong author Xu Xiby Susan Blumberg-Kason 37Book Reviewsby Susan Blumberg-Kason 4015ASIAN JEWISH LIFE ISSUE 111

InBoxDear Editor:Here’s an update to Craig Gerard’s article (Playing <strong>Jewish</strong> Geography inPhnom Penh- The redevelopment of a community) you’re your September2011 issue.Rav Butman and Rabbanit Butman and family have been running ChabadHouse in Phnom Penh, Cambodia now for several years. Located in thecenter of the city, Kabbalat Shabbat services begin around 20 minutesafter sundown. At least 35 people usually attend and join the Shabbatdinner. Many stay and chat afterwards too. Shabbat morning servicesstart at 10 am and are followed by kiddush. Numbers vary, but there areusually about 15 participants. (You should give them a heads-up if you area group of more than four.) You can find their contact info on the websitebelow.There is a kosher restaurant on site, computers with internet accessand many kosher products for sale. Challah is available on Friday. LuckySupermarket (the closest one is on Sihanouk Blvd./63rd Street) has quitea few kosher products, as well, but if you are a dairy lover, you’ll have tobring your own.RockyDear Rocky:Thanks so much for updating us. We will definitely pass this information along.We get many requests from readers looking for local information for where theirtravels take them.All the best,EricaYour opinion mattersPlease tell us what you think. Write to us atletters@asianjewishlife.orgA young Israeli boy from the BeneIsrael community celebrates his BarMitzvah in Israel. Photos courtesy ofYoraan Rafael Photography.How to reach us:Onlinehttp://www.asianjewishlife.orgEmail us:info@asianjewishlife.orgOn Facebook:https://www.facebook.com/<strong>Asian</strong><strong>Jewish</strong><strong>Life</strong>On Twitter:at <strong>Asian</strong><strong>Jewish</strong><strong>Life</strong>COPYRIGHT <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Jewish</strong> <strong>Life</strong> is the sole title published by <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Jewish</strong> <strong>Life</strong> Ltd. © Copyright2010. Written material and photographs in the <strong>magazine</strong> or on the website may not be used orreproduced in any form or in any way without express permission from the editor.Printed by: Fantasy Printing Ltd. 1/F, Tin Fung Ind. Mansion, 63 Wong Chuk Hang Rd, Hong Kong.DISCLAIMER <strong>AJL</strong> does not vouchfor the kashrut of any product in thispublication.2 ASIAN JEWISH LIFE ISSUE 11

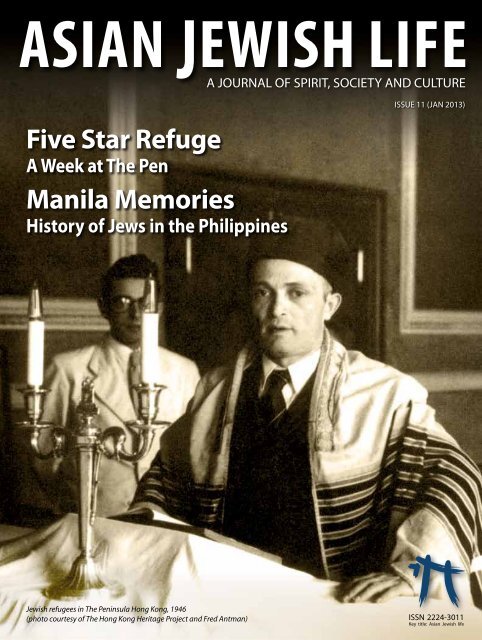

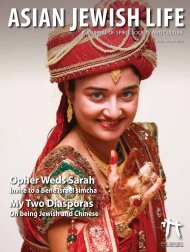

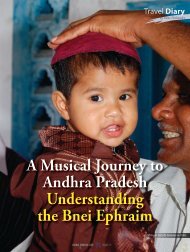

EditorMissionDear Readers:Happy 2013 and welcome to the 11thissue of <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Jewish</strong> <strong>Life</strong>.In between issues, our staff has beenvery busy speaking on <strong>Jewish</strong> life in Asiaand <strong>Asian</strong> Jewry. If you happen to be inIllinois, you can catch <strong>AJL</strong> Books EditorSusan Blumberg-Kason at a NCJW eventon January 31 where she will talk aboutJews in China and their contributionsduring World War II. She will also discuss<strong>Jewish</strong> novels and memoirs set in Chinaduring this world-changing era. VisitSusan at http://www.susanbkason.comfor more information.You can also catch a podcast on HongKong’s RTHK Radio 3 on Laura Margolis,adapted from our cover story (Issue 8),entitled Laura Margolis in the Spotlight-Portrait of a heroine in Shanghai. I willalso be headed to Moscow in Februaryto participate in the 20th AnnualInternational Conference on <strong>Jewish</strong>Studies organized by Sefer, the MoscowCenter for University Teaching of <strong>Jewish</strong>Civilization.Please follow us for a daily dose of newson our Twitter and Facebook pages (@<strong>Asian</strong><strong>Jewish</strong><strong>Life</strong>).As for this issue, we are excited to bringyou the cover story about the somewhatobscure story of a group of <strong>Jewish</strong>Holocaust refugees that were housedin Hong Kong’s Peninsula Hotel, entitledFive Star Refuge- A Week at The Pen.We also have included the little knownhistory of Jews in the Philippines byBonnie Harris, Manila Memories -Historyof Jews in the Philippines. As Dr. Harrishas done extensive research on thissubject, we will explore this history, ingreater depth, in an <strong>AJL</strong> series in futureissues.Also travel with musician Irene Orleanskyfor a rare inside look at the Bnei Ephraimin A Musical Journey to Andhra Pradesh-Understanding the Bnei Ephraim.Also from India, we bring you A Memento,a beautiful short story by Sophie Judah.Judah is the author of Dropped fromHeaven (Schocken, 2007). A specialthank you to Yoraan Rafael Reuben forthe use of his photographs to go alongwith Judah’s story. His photographs alsoappear on Page 2.Again from India, we have our LoMein toLaksa food column. Yardena Ben-Israeloffers her modernized version of BeneIsrael Halwa, which she calls ‘sweet andsimple’.On the literary side we have includedbook reviews by our Books Editor SusanBlumberg-Kason as well as her interviewof Xu Xi. Xu Xi, a Hong Kong writer, hasinterestingly woven <strong>Jewish</strong> charactersinto her novels and we have discussedwith her why. (Being Hong Kong-based,we are also not quite impartial when itcomes to all things Hong Kong.)In this issue, we also hear from GedaliahGurfein, who has had some of his worktranslated into Chinese in Not Lostin Translation - A Torah scholar goesto China. And while we are looking atChina, we hear from Tiberiu Weisz inBiblical Influence in Chinese Literature,a continuation of his <strong>AJL</strong> series thatagain explores the fascinating yin andyang relationship between Chinese and<strong>Jewish</strong> cultures.Last, but definitely not least, For the Bestof <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Jewish</strong> <strong>Life</strong> feature, we look atthe incredible regional work of AJWS inFeeding the World with <strong>Jewish</strong> Wisdom-A look at American <strong>Jewish</strong> WorldServices.Thanks for reading!Erica LyonsEditor-in-ChiefASIAN JEWISH LIFEA JOURNAL OF SPIRIT, SOCIETY AND CULTUREFive Star RefugeA Week at The PenManila MemoriesHistory of Jews in the Philippines<strong>Jewish</strong> refugees in The Peninsula Hong Kong, 1946(photo courtesy of The Hong Kong Heritage Project and Fred Antman)<strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Jewish</strong> <strong>Life</strong> is a freequarterly publication designed toshare regional <strong>Jewish</strong> thoughts,ideas and culture and promoteunity. It also celebrates ourindividuality and our diversebackgrounds and customs.<strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Jewish</strong> <strong>Life</strong> is a registeredcharity in Hong Kong. <strong>AJL</strong> is alsounder the fiscal sponsorship ofthe Center for <strong>Jewish</strong> Culture andCreativity, a qualified US 501(c)(3)charitable organization.Editor-in-ChiefErica LyonsCopy EditorJana DanielsBooks EditorSusan Blumberg-KasonPhotography EditorAllison HeiliczerDesignerTerry ChowISSUE 11 (JAN 2013)Board of DirectorsEli Bitan, Bruce Einhorn,Peter Kaminsky, Amy Mines,David ZweigISSN 2224-3011Key title: <strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Jewish</strong> lifeASIAN JEWISH LIFE ISSUE 113

Featureby Bonnie M. Harris, Ph.D.Photo credit: <strong>Jewish</strong> Historical Society of San DiegoManila MemoriesHistory of Jews in the PhilippinesTemple Emil, Manila, April 1940In the late 15th and early 16thcenturies, Portuguese vesselscarried Sephardic <strong>Jewish</strong>merchants for the first time downthe West Coast of Africa, around the hornand up the East Coast, and the across thePersian Gulf and Indian Ocean to India,China, the Spice Islands of Indochina,and to the as yet unnamed islands ofthe Philippines. These Crypto-<strong>Jewish</strong>merchants escaped the persecutionsof their time by migrating ubiquitouslyfrom the Iberian Peninsula to commercialports scattered throughout the world.Even before the arrival of these firstEuropeans in the Philippine archipelago,the socio-political fate of the Philippineswas destined to be contested by theSpanish and Portuguese by virtue ofthe Treaty of Tordesillas that attemptedto divide all New World discoveriesbetween Spain and Portugal in the late15th century. Disputes between theIberian fleets over the Philippines andits neighboring islands, the Moluccas,resulted in the 1529 Treaty of Zaragoza,in which Portugal ceded the Philippinesto Spain, which would remain underSpanish control for nearly four hundredyears. Nevertheless, the Portugueseenjoyed an economic presence withinthe Spanish realm by virtue of <strong>Jewish</strong>merchants fleeing the Spanish Inquisitionvia Portugal to the New World. Medievaltexts reveal that 180,000 Jews fledSpain and that of these, 120,000 enteredPortugal raising the <strong>Jewish</strong> populationnumbers to 15% of the total population.iWhen these Spanish <strong>Jewish</strong> refugeesencountered a litany of extreme abuses,many accepted a forced conversionto Christianity as a means to escapedeath and eventually to escape Iberia –becoming explorers, mathematicians,cartographers, and especially merchantsabroad Portuguese and Spanish vesselsen route to New World ports – Manilabeing one.When Marranos or New Christians,other distinctions for the conversos orCryto-<strong>Jewish</strong> merchants, reached thePhilippines they no doubt engaged in theSpanish Galleon trade between Manilaand Acapulco.ii The New Christianbrothers Jorge and Domingo Rodriguez4 ASIAN JEWISH LIFE ISSUE 11

Best of <strong>AJL</strong>by Erica LyonsFeeding the Worldwith <strong>Jewish</strong> WisdomA look atAmerican <strong>Jewish</strong>World ServiceAJWS grantee8 ASIAN JEWISH LIFE ISSUE 11

Best of <strong>AJL</strong>by Erica LyonsThere seems to be an implicitunderstanding that ourplanet is divided into twoentirely separate worlds,there is an ‘us’ and a ‘them’. The thirdworld is the ‘them’, which we can tuneout, address or not address, engagewith or ignore. But Ruth Messinger,CEO/President of American <strong>Jewish</strong>World Service (AJWS), an internationaldevelopment organization motivated byJudaism’s imperative to pursue justice,does not divide the world in that way. Asshe explains, as Jews we simply can’tdo this. “<strong>Jewish</strong> texts are very clearabout this. Jews have a clear obligationto work towards global justice, to helpboth Jews and non-Jews.Everyone has been made in God’simage (b’tselem elohim).”AJWS granteeListening to Ruth Messinger of AJWSespouse <strong>Jewish</strong> wisdom and Talmud,on the surface the way her messageis expressed sounds different fromthe Ruth Messinger of New York Citypolitics where she first made a name forherself. But even though her diction ismuch more haimisha, the message isvery much the same. As she explains,it was her years of experience andadvocacy within New York City thatpaved the way for her pursuit of globaljustice. Many of the skills she relies onin doing international development workfor AJWS, came directly from her yearsworking in government. Messingermade a seamless move from citydevelopment to global development,seeing the former as more of acontinuation of her raison d’être but juston a different scale.“A big piece of what I did in New York Citypolitics was to look at pockets of povertyin a rich city and try to understand howgovernment could empower thesepeople to do for themselves.”While the phrase tikkun olam might nothave been included in her New YorkCity campaigns, her core values havecarried through.Often though it is not only about thework that is being done but also howit is approached. Messsinger, and theorganization as a whole, approach theirwork with some of the world’s neediestand most marginalized people with asense of true humility. “Don’t go and telleveryone what they need,” seems to beMessinger’s mantra.AJWS granteeAnd everyone is their focus. “Whenone billion people go to bed hungry,we need to talk about ethics. This is aglobal issue.” So AJWS thinks globally,operating in countries throughout theAmericas, Asia and Africa but effect realchange in small communities throughgrassroots efforts and by working withover 200 local NGOs in a diverse rangeof projects.Asia is of course a large focus for them.Regionally, they are primarily focusedASIAN JEWISH LIFE ISSUE 119

Best of <strong>AJL</strong>by Erica Lyonson five countries: Burma, Cambodia,India, Sri Lanka and Thailand. In eachof these countries they have localrepresentatives who are best equippedto assist in identifying potential grantees,to monitor the grantees’ work and toprovide them with support in terms ofcapacity development and networkingopportunities. This list of countrieshowever is not exhaustive. Perhapssomewhat surprisingly, as a <strong>Jewish</strong>organization, they also have providedfunding for grassroots organizationsin Aceh, Indonesia and even Pakistan.The work in Aceh was focused on posttsunamidevelopment and the workin Pakistan began in 2005 focusedon emergency relief for earthquakevictims. They also provided assistancein Pakistan in 2007 and 2010 withfunding for disaster relief after massiveflooding ravaged the country. Workingin Pakistan has not been without extraordinarychallenges. Security concernswere raised both with the content of theirpartners’ work as well as their affiliationwith AJWS, a <strong>Jewish</strong> organization. Thedecision was therefore made not topublicize the names of these grantees.AJWS granteeIn their response to the Indian OceanTsunami, it was not only about disasterrelief, AJWS was at the forefront ofreconstruction work. As Messingerpoints out, as an organization they werethe first on the ground actually replacingfishing boats and nets, helping localpeople to begin to rebuild their lives.This is their model. They aim to movequickly from the initial and necessaryemergency relief work into the nextphase, which is engaging in developmentwork post-disaster that will have a longtermimpact on recovery. They specificallyfocus on projects that promote changefrom within and empower local peopleby funding grassroots/community-ledorganizations primarily focused on: civiland political rights, natural resourcerights and healthcare.Their grant making is guided by severalmain principles. They strongly believethat grassroots organizations arein the best position to evaluate andarticulate their own needs. Likewise,they are the ones able to put theseprograms into place and drive them.Real change is made when it comesfrom within through the empowermentof marginalized people. In the same vein,AJWS recognizes that while womenstatistically are more marginalized thantheir male counterparts and suffer moreAJWS granteefrom the effects of poverty, hunger anddeprivation, when empowered theyare real change makers. Unfortunatelythough, issues of gender-based violenceand oppression, particularly in developingcountries, often impede women frombecoming the positive force for changethat can improve their societies. AJWSis very vocal about the need to addressissues like gender-based violence andoppression in order to overcome theobstacles they create in the fight forglobal justice. They know that nothing10 ASIAN JEWISH LIFE ISSUE 11

Writer’sDeskby Sophie JudahA MementoSarah is cleaning her house before Passover. Herniece Daisy is helping her because Sarah hasreached the age of eighty-three and it has becomea difficult chore for her. Daisy does the scrubbingand washing and leaves her aunt the task of going throughsuitcases full of unused clothes. Sarah sits upon a chair in frontof a metal trunk which has been placed upon an old woodenbench because her back hurts when she bends over. Theclothesline is full of linen that needs fresh air and sunshinebefore it will be packed away for another year. A basket fullof clothes that Daisy will distribute to the poor of the villagestands beside the door.Sarah’s hands stop moving when they come in contact witha little yellow suede bag. Her fingers close around the objectand she sits back in her chair. Her mind wanders back to thetime when she was a young girl living with her aunt and unclein the Dadar district of Bombay.“Sarah, you have an offer for marriage,” Miriam, her aunt hadsaid to her. “He is a nice young man from an observant <strong>Jewish</strong>family. He has a steady job with the Naval Dockyard and will beable to support you and your future family.”Sarah looked up from her sewing. She recognized the worrybehind her aunt’s eagerness for an answer. “I don’t know if I amready for marriage,” Sarah said.“You are already nineteen years old. I was married at sixteen,”Miriam replied.12 ASIAN JEWISH LIFE ISSUE 11

Writer’sDeskby Sophie Judah“That was a generation ago, Auntie. I don’t know the man youare asking me to marry. When and where did he see me?”“You remember the malida the Solomon family had before themarriage of their daughter. This young man and his family sawyou there.”“Who is he?”“His name is Joseph Varoolkar. Your uncle and I have madeall the inquiries. We find him entirely suitable. Your father hasalready agreed but I insisted that you meet the boy before wegive our answer. I’ve raised you ever since your mother died. Iintend to make sure that none of my daughters will be marriedwithout their consent. I’ll see to it that you will not be forced tomarry a boy you do not like.”“I want to see him first.”Miriam took Sarah to her cousin David’s home which was closeto the railway station from where Joseph took the train home.He had been invited to ‘drop in for a cup of tea’ after work.Sarah fidgeted with embarrassment as she sat and waited forhim to arrive.“Don’t worry. He does not know that you are here. You said thatyou wanted to see him as he really is. What did you mean bythat?” David asked.“I did not want him to dress up or be under any kind of pressure.”“Perhaps she is referring to our combing her hair into a bun,”David’s wife laughed.“She did not want to wear my new sari,” Miriam added. “I don’tunderstand why she says she feels uncomfortable in it.”There was a knock at the door. Joseph stood there dressed innavy blue cotton trousers and a white bush-shirt. There was ablue ink stain on the shirt pocket where his fountain pen hadleaked. He shook hands with everyone he was introduced to.“Sarah. That was my grandmother’s name,” he said as he tookher hand. He had a firm and warm handshake.She smiled shyly. She recognized him, but not from themalida. She remembered a day three months earlier whenshe was in a jeweler’s shop with her cousin Suzie. Suzie hadtried on different earrings in front of a mirror and a very patientif slightly irritated salesman. She turned around from time totime for Sarah’s opinion.Two men had walked into the store. The older one did all thetalking. He inspected several gold bracelets but insisted thathe would only buy a pair that had an old fashioned design.Sarah thought that they were buying something for an aunt ora grandmother. She caught a glimpse of his final choice beforethe salesman slipped it into a little yellow suede pouch anddrew the drawstrings. The design was of a gold braid fixedupon the flat broad bangle beneath. They made their purchasebefore Suzie decided which pair of earrings she wanted.Suzie saw her friend Radha waiting at the bus stop. Shewas delighted. The two girls had not seen each other sincetheir schooldays. Suzie ran across the road causing a taxi toscreech to a halt and its driver to shout, “Are you crazy?” Sarahfollowed more cautiously. Ten minutes later the three girls sat inthe ice-cream parlor called Joy. Suzie and Radha chatted andcaught up on the news about their other classmates. Sarahrested her head on the back of the booth. She did not knowSuzie’s friends. She had continued in the school where shestudied before she came to live with her father’s older brotherand his family. She could clearly hear a voice from the adjoiningbooth. She immediately recognized it as the voice of the olderman from the jeweler’s shop.“You should understand the reasons behind this purchase,”she heard. “You have to make the girl feel important as part ofa tradition. She will not know that the bracelets did not reallybelong to your grandmother. She will think of you as a man whovalues and respects all the members of his family. If you arerespectful of your grandmother’s wishes and family traditionsyou will be respectful of your wife’s wishes and traditions she isattached to too. If you are the kind of man who takes care of hisfamily you will naturally take care of her and your children also.”Sarah could not hear what the younger man said. Then theolder one replied, “I know that you are getting married for yourmother’s sake and not your own, but which young girl will agreeto that? They all want something romantic in their lives. Believeme, no girl will be willing to leave the city and go to a village tocare for your mother and your fields. I know what I am doing.”The other man must have said something about the newappearance of the bracelets because she heard the answer,“We will say that we have had them cleaned. Remove themfrom the jeweler’s pouch. It has his name and address on it. Ifthe family decides to trace it they’ll discover the truth.”The men paid their bill and left. Sarah heard the waiter’scomment about the smallness of his tip. When they rose toleave she peered into the booth the men had occupied. TheASIAN JEWISH LIFE ISSUE 1113

Travel Diaryby Irene OrleanskyIhave always been fascinated by thestory of the lost tribes and wishedto contribute to their return to Zion.Being neither an anthropologist nor apolitician, I decided to go about it using myown talent, music. That is how in Januaryof 2012, equipped with a small mobilestudio, I came to start my journey throughAfrica and Asia to record a CD of musicof the lost tribes. After visiting the AfricanHebrew communities in Ghana, Uganda,Kenya and Ethiopia and then Kaifeng,China my next destination was India.After visiting and recording the music ofthe communities of Bnei Israel in Mumbaiand Bnei Menashe in the North Easternstate of Manipur, my last destinationwas the community of Bnei Ephraim, theTelugu Hebrews of South India.The Bnei Ephraim live in a few villagesand towns of Andhra Pradesh. Thefirst stop of my trip was a village nearChebrole in the district of Guntur, apoor village of mud houses adornedwith menorahs and the Stars of Davidand a small white building, the BneiYaakov Synagogue, where I observedYom Kippur and Shabbat. The secondstop was the suburbs of the townMachilipatnam on so called SynagogueStreet where there is a larger synagogue,where I spent Sukkot. My third and finalshort stop was the slums of the townVijayawada, where I was welcome bythe leader and founder of the communityShmuel Yacobi at his home.What really struck me during my visitwas the contrast between the povertyof the community members and theirgenerosity, kindness and cordiality. Thesari that the Bnei Ephraim gave me formy birthday will always be the sari that Iwear for my most joyous and significantevents. So it was was in the poor huts andslums of Andhra Pradesh, wrapped in aroyal sari and surrounded by numerous“Yiddishe Mamas” of both genders,constantly worrying about whether myplate of rice is full, that I started mybitter-sweet journey into the past and thepresent of the Bnei Ephraim.The Bnei Ephraim are a small communityof about sixty families that practiceJudaism and are part of the tribes Malaand Madiga that follow different religions,mostly Christianity. These tribes are socalled untouchables, also called in IndiaDalits, which means “broken to pieces”.Though untouchability is prohibited bythe constitution of India, in the democraticIndia of the 21st century, they are stillvery much deliberately discriminatedagainst, humiliated and literally brokenby the Indian caste system.Scenes from a village near ChebroleMuch of what I learned about thecommunity, I learned from ShmuelYacobi, the leader of the communitywho carefully studies and records thetraditions of the Bnei Ephraim. He wasthe first of the community to completeuniversity where he obtained severalbachelors degrees as well as a Master ofArts in Philosophy. His father, a subedar(an officer rank) in the British army,was able to save money to educatehis son. For forty years Shmuel hasbeen dedicating his life to exploring thehistory of his people, basing his researchon ancient Hindu, Buddhist, <strong>Jewish</strong>and Christian literature. In our privateconversation at his small and clean16 ASIAN JEWISH LIFE ISSUE 11

Travel Diaryby Irene Orleanskycommunity, I could not stop wonderinghow in total isolation, against constantpersecution and with little support fromworld Jewry, the Bnei Ephraim maintainsuch a deep connection to Judaism.Touched by their depth of determination,faith and kind-heartedness, I developeda special bond with the community.They accepted me as their sister and Ialso accepted them as my family. I wastouched by their communal strugglesas untouchables but also by theirindividual stories.I think of Ovadia Kudara, 37, who liveswith his wife and three children in avillage close to the town Visakhapatnam.Though he got his B.A. degree andworked in a governmental institution asa social worker, he decided to leave hisjob, since his job required working onShabbat. In his village, his family is theonly one practicing Judaism, a religionunknown to the local institutions.Ovadia sees the only solution inspiritual understanding of the issue,and therefore is totally dedicated tostudying Judaism.Building a sukkah at Bnei Yaakov SynagogueYaakov Yacobi, 38, lives with his wifeand children in Chirala town. Whentalking about his challenges, hementioned that he was discouragedwhen his visa to Israel was cancelledalong with the other Bnei Menashe in1994 and his family’s repatriation filewas delayed indefinitely.Yachin Raju Vepuri, 23, lives with hisparents, two sisters and a brother in avillage near Srikakulam. His parents rentfields where they grow rice and lentils.Yachin had to leave his college where hewas studying electronic engineering tohelp his family at the farm. While still inschool, he was continuously humiliatedby students of higher castes.Chandrababu Kale, 28, fromKunchinapalli village, tells that thoughhe has his degree from an IndustrialTraining Institute in the field of electricaland communicational engineering,he works at a construction materialfactory and is paid less than otherworkers in the same position which heattributes to caste discrimination. Whilea student though, Chandrababu alsobecame interested in photography andhis hobby has become a part-time job.(Chandrababu provided most of thephotographs for this article.)Returning to Judaism created additionalBnei Ephraim homes near Chebroleproblems for Bnei Ephraim. There is atense relationship with the Christianscommunities to which most of Malaand Madiga belong. As Shmuel Yacobiexplained, “They express love outwardlybut expect us to embrace Christianity.They always hate us inwardly.” In 2003there was an attempted terrorist attackagainst the community by a Muslimterrorist organization. Another problemis the burial grounds. According to thelaws of Andhra Pradesh, a burial groundis given according to the caste or tribe.Christians have a burial ground and this18 ASIAN JEWISH LIFE ISSUE 11

Travel Diaryby Irene Orleanskyis the only place where Bnei Ephraimcan bury their dead as the otherfaiths cremate their dead. The <strong>Jewish</strong>graves are constantly vandalized. Thecommunity has requested their ownburial ground for many years, but havebeen denied because Judaism is nota registered religion in the State ofAndhra Pradesh.The synagogue in Machilipatnamreceives little support, aside fromvery small donations for their buildingand siddurim that have been donatedfrom several <strong>Jewish</strong> organizations.For those that think that Bnei Ephraimadopted Judaism in an attempt toimprove their economic conditionand escape discrimination, they areobviously mistaken.Miriam Yacobi and Irene OrleanskyEven though their return to Judaismbrought additional economic and socialstrain to the Bnei Ephraim, it is from theirfaith that the community members drawstrength and motivation to overcometheir difficulties. During long hours ofintense conversation they shared theirchallenges, dreams and hopes with methrough words and song. Among theirhighest aspirations and dreams, all thecommunity members named studyingthe wisdom of the Torah and their returnhome to Israel. Their faith also inspiresthem to move towards prosperity.Identifying with their pain and shatteredhopes, I became one of them, a daughterof Ephraim, an untouchable, in theenigmatic land of snake charmers, yogisand maharajas.JAL_ad_200x265_Sept2012_OP.pdf 1 04/09/2012 3:36 PMCMYCMMYCYASIAN JEWISH LIFE ISSUE 1119CMY

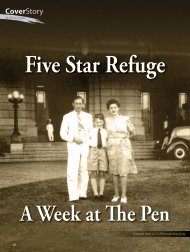

CoverStoryby Erica LyonsFive Star RefugeA Week at The PenA refugee family at The Peninsula Hong Kong20

CoverStoryby Erica LyonsHigh Holidays at The Peninsula, 1946The lobby of Hong Kong’s Peninsula Hotel (or “ThePen” as it is often fondly referred to as) suggeststhe height of colonial elegance, framed by gildedcolumns with its marble flooring and high ceilingscomplete with ornately carved scenes. As the string quartethums from the grand balcony above, over shiny silver threetierstands of high-tea treats, with its grandeur and elegance,it is difficult to imagine that the Peninsula Hotel was once atemporary shelter for post-World War II <strong>Jewish</strong> refugees.And while Hong Kong’s Peninsula Hotel is but a very small partof the larger story of the <strong>Jewish</strong> refugees in China, it bringstogether the best of Hong Kong in the most unexpected way.In recent years, there has been considerable attention drawnto the remarkable history of Jews who escaped the Holocaustby fleeing to Shanghai. Beautiful stories emerge of two diversepeoples coming together in trying times in an effort to survivethe darkest period in history.Left on their own, the <strong>Jewish</strong> refugees lucky enough to makeit to Shanghai faced seemingly unbearable obstacles andchallenges. These burdens were however eased by the reliefwork of the American <strong>Jewish</strong> Joint Distribution Committee(JDC) with assistance from the established <strong>Jewish</strong> communityof Shanghai, and most notably through the efforts andresources of Horace Kadoorie.The end of the war marked the beginning of a massiverelocation plan for the nearly sixteen thousand <strong>Jewish</strong> refugeesin Shanghai. Though eager to leave Shanghai, especially inthe shadow of the looming internal upheaval in China, theyrequired documentation and visas for their final destination aswell as transportation arrangements and the necessary fundsto pay for their journey.For many of the refugees, passage was secured using HongKong as a transit port. This was far from ideal as they lackedthe necessary paperwork to even stop over in the colony. Onthe Hong Kong side, Lawrence (later Lord) Kadoorie, Horace’sbrother, worked with the JDC who was coordinating thetransportation as well as sponsoring it in most cases. Kadooriealso interceded on the refugees’ behalf before the local HongKong government to obtain the proper authorization for therefugees to stay in Hong Kong while in transit.Special arrangements, however, were required for eventhe short accommodation of the refugees. LawrenceKadoorie responded to the crisis by coordinating temporaryaccommodations for refugees in the Peninsula Hotel inKowloon. A letter from Horace Kadoorie, in Shanghai, to hisbrother in Hong Kong dated 7 May 1946 references some22 <strong>Jewish</strong> refugees that had secured visas and passage toAustralia but their route would require them to stay over inASIAN JEWISH LIFE ISSUE 1121

CoverStoryby Erica LyonsHong Kong for a few days. The housing crisis in Hong Kongwas acknowledged, but Horace suggested, ”Maybe they couldstay at the Pen and some kind of lady could look after them. Allexpenses, of course, would be met by the Joint [JDC].”Charles Jordan, the JDC representative, further reassuredLawrence Kadoorie, via letter of May 15, 1946, “We are notplanning to send anymore refugees via Hong Kong except onalready limited resources. Transit visas were a must and camewith strict limitations on time and privileges.In a letter on July 4th, 1946, after accommodating the needsof another small groups of refugees in transit, LawrenceKadoorie offers to reserve three rooms for $800 per montheach, paid in advance, for the JDC’s use. The rooms wouldaccommodate 10-12 persons “with a squash”. He furthersuggested that Mr. Jordan consideropening an account in Hong Kong tohelp streamline the payment process.It was further agreed that food couldbe provided for the cost of $5.50 perperson per day. To supplement this, itis documented that the JDC also sentmany of the refugees with $50 each inpocket money.definite shipping facilities, because we realize the difficultieswhich will be created by such people having to remain in HongKong for indefinite periods of time…”There are several pieces of correspondence that refer to smallgroups of <strong>Jewish</strong> refugees in transit who were accommodatedin this manner. Somewhat ironically in light of events that wouldsoon come to pass, in a letter from Lawrence Kadoorie to Mr.Jordan of May 30, 1946, he writes,” The possibility of openinga hostel for future refugees passing through the colony hasbeen discussed, but quite frankly it would be difficult, if notimpossible, to arrange for this.”And even for those for with a promise of room and board by theKadoories, despite their influence, it was by no means a legalright to stay in the colony as the city was already brimmingover with displaced persons as well as British being repatriatedand there was a concern that the refugees would compete forA party for refugee children, 1946On a case-by-case basis the Kadooriesworked with the JDC to take care ofthe special needs of the refugees. Insome cases this meant arranging forindividual seats on flights. In othercases, hospitalization was requiredand, for some, burial in the HongKong <strong>Jewish</strong> cemetery was eventuallyrequired. It was suggested that anadditional small fund for emergencyuse be developed to allow for theKadoories to meet these special needsof the refugees.Despite these well thought out plans,nothing could prepare either the JDCor the Kadoories and The Peninsula for the events of July 1946.Arrangements were made for approximately 250 refugees (theexact number was not initially known) to travel to Australia viathe S.S. “Duntroon”. While it was assumed that the Duntroonwould sail from Shanghai, by mid-July 1946, it became clearthat this was not possible and the Duntroon would insteaddepart from Hong Kong. Arrangements were made betweenthe Kadoorie brothers to accommodate this group of 250refugees as a stay over in Hong Kong would be the only wayfor them to secure their passage on the Duntroon and finallymake their way to Australia.By way of correspondence between Charles Jordan andLawrence Kadoorie, additional details were ironed out and anunderstanding reached. Both parties understood that in orderto obtain approval from the Hong Kong government for thishighly irregular stopover, there must be a detailed plan in placeand assurances that the refugees’ needs would be met and22 ASIAN JEWISH LIFE ISSUE 11

CoverStoryby Erica Lyonsthe group would be kept in order. The group was scheduled toarrive in Hong Kong on July 30th via the “General Gordon” andthen leave on the S.S. Duntroon on or about August 5, 1946.Further arrangements were made to send each refugee in needwith $30 of pocket money. Additional money was also set asidefor emergency funds including medical expenses. On July 27,1946, the final numbers were reported to The Peninsula andthe group was to consist of 283refugees: 141 men, 125 women,15 children and 2 infants.they thought would be a week, were to remain in the colony,some for as long as through December of that year. Initiallythere were discussions about whether or not to return theserefugees to Shanghai, as the Duntroon’s delay was indefinitebut the JDC and the Kadoories knew that there was a far betterchance of finding transport from Hong Kong and a return toShanghai would only further prolong their ordeal. Withoutvisas, the refugees were unable to earn money leaving themGiven the room shortage in HongKong generally, arrangementswere made to house the refugeesin the hotel’s ballrooms. The 6thfloor’s Roof Garden would beutilized for men and the RoseRoom for 108 women. Theremaining 17 women as wellas 15 children and two infantswould be housed in the Surgeryon the Mezzanine Floor. RichardFlantz, who was ten years oldat the time, recalls sleeping on“paliasses, like sort of strawmattresses”. Records reflect‘camp’ cots were used.There was “ample” toilet spaceon the 6th floor in the “Gents andLadies Cloak Rooms” as well astwo baths in the Surgery on theMezzanine Floor. A meal schedulewas arranged as well: Breakfast from 7-8, ‘Tiffin’ from 11:30-12:30 and Dinner from 6-7. The refugees were advised to onlybring light baggage with them, as their heavy luggage wouldbe transported directly to the godown (dockside warehouse).Dormitory in The Peninsula ballroomWhile these arrangements were far from ideal, they certainlywere ample to provide for the refugees’ needs for their brief stayin the colony. While still in the process of settling the refugees,on July 31, 1946, Lawrence Kadoorie writes in his privatediary, “ I spent several hours in the godown attending to theirluggage. Have just reached the office and had a bombshell…the Australian Government has cabled that it intends towithdraw the Duntroon as it is needed to carry military to NewGuinea and will not be allowed to take passengers back toAustralia.” Kadoorie concludes the entry by stating, “HongKong now has its own refugee problem!”And so the 283 refugees, settled in the Peninsula Hotel for whatto rely almost entirely on the basic food and modest suppliesprovided by the hotel staff. The Hong Kong <strong>Jewish</strong> community,though also still readjusting to postwar life, assessing theirown loss and damages and for many fairly newly returned fromJapanese internment camps, quickly mobilized themselves tosupplement the efforts of The Peninsula.A <strong>Jewish</strong> Women’s Association was immediately conceived tohelp distribute good to the refugees. Mrs. J. Frenkel served aschair this new organization which is referenced several timesin the Kadoorie’s correspondence for their role in providing therefugees with much needed essentials as well as extras likebaskets of fruit and candy. In later correspondence, the work ofother women in the newly formed organization are cited, namelyDr. Sophie Bard, Mrs. Godkin, Mrs. Frenkel and Mrs. Poliak.Mr. Lew Cohen served as the local <strong>Jewish</strong> Welfare Officer andCaptain Hebert, of the national <strong>Jewish</strong> Welfare Board, likewisealso played leading roles in seeing that needs were met.ASIAN JEWISH LIFE ISSUE 1123

CoverStoryby Erica LyonsHigh Holidays, 1946But the efforts were by no means limited to those in officialcapacities or to those in the newly formed organization. Mr.Weiss, a prominent member of the community, arranged a junk(leisure boat popular in the colony) outing and picnic for thechildren and their mothers in August. Lawrence Kadoorie alsoreported to Mr. Jordan that transportation for 60 was beingarranged to take some of the refugees to his own home for apicnic and swim in the later part of the month. Richard Flantzrecalls a local member of the Hong Kong <strong>Jewish</strong> communitytaking him for ice cream for his first time and taking him toswim, another first for him, out at Repulse Bay. Additionally,it should be remembered that this was a resourceful groupof survivors who demonstrated the ability to not merelysurvive but to live life to the fullest despite the deprivationsthey suffered in Shanghai. There are even stories of refugeeorganizedmarkets for trading goods in the hotel’s lobby.Fred Antman, now living in Australia, was also among thisgroup of 283 refugees. Born in 1930 in Germany, he was but16 years old at the time of his family’s unplanned extendedstay in The Peninsula. He recalls, “The staff of the hotel wasfantastic... And I could not speak more highly of them asthe, the hotel staff looking after us in a very awkward sortof a situation, you know. We had a <strong>Jewish</strong> New Year festivalcoming on and there is a very big day in the <strong>Jewish</strong> calendarand they made a certain provision for a room available to us,which we used to conduct our holy services, which we did.And they even provided us with a very festive meal on thatNew Year’s night; a little different to what we had previously,you know, but they could not do enough for us you know, andI, I will never forget the, the, the wonderful manner in whichalmost like brotherly love, that came from them looking afterus.” He speaks fondly of memories of football matches againstThe Peninsula Hotel staff.Overall though, despite the best efforts of the hotel, theKadoories, the JDC and the Hong Kong <strong>Jewish</strong> community,this group of refugees were weary and grew restless andtired of living in a state of impermanence. Their one-weekstopover in late July had now seen them through all of thesummer and through the <strong>Jewish</strong> High Holidays. A request, viacorrespondence in September 1946, was made by the <strong>Jewish</strong>community of Manila to the Kadoories to begin moving some oftheir refugees through Hong Kong. Despite the willingness onthe part of the Kadoories and the local <strong>Jewish</strong> community, thissimply was inconceivable at the time given how far tight spaceand resources had already gone not to mention the flexibilityon the part of the Hong Kong government in agreeing to allowthe refugees to enter the colony in the first place and then theirwillingness to allow them to stay on for so long beyond the stayof an ordinary transit visa. By September, arrangements beganto be finalized to finally move the refugees on to Australia but24 ASIAN JEWISH LIFE ISSUE 11

Lo Mein to Laksaby Yardena Ben-IsraelBene Israel Halwa -Sweet and simple26 ASIAN JEWISH LIFE ISSUE 11

Lo Mein to Laksaby Yardena Ben-IsraelCorn flour halwa is actuallythe easier version of themore traditional and popular`Chikha cha Halwa’, which ismade from wheat but involves a moredifficult and time consuming process.I learned these recipes from from myhusband’s Aunt Rosy. Rosy Aunty iswell known throughout the communityfor her excellent traditional cooking andalways makes fabulous cakes for everyoccasion. For parties, she comes up withwonderful snacks and dishes, mostly herown invention; how all the family waitsfor her to bring her latest surprise dish.In the Bene Israel community, halwais a signature dish and a specialty forRosh Hashanah, but it is also preparedduring many special occasions likemarriages, mehndi ceremonies whichtake place a day before weddings, britmilahs, bar mitzvahs, anniversariesand house warming ceremonies. I havemany wonderful memories of eatinghalwa or helping to prepare it for suchspecial occasions.During Rosh Hashanah halwa isdistributed among relatives and friendsand even my non-<strong>Jewish</strong> friends wait formy chocolate halwa as it has become mysignature dish thanks to Aunty Rosy.Coconut halwa is another Bene Israelspecialty. Many Bene Israel dishes(sweets, main dishes, deserts) containcoconut as the main ingredient sincecoconut is found in abundance in KonkanCoast. Today it is still an importantpart of many Bene Israel’s traditionalcelebrations wherever we travel.Corn flourCoconut Halwa• Corn flour – 250g• Sugar – 350g• Coconut milk – 2 liters• Pistachios & almonds – 1 tbspeach• Edible color – pink or orange(3 to 4 drops)• Cardamom powder – Half tsp• Nutmeg – ¼ tsp• Salt – ¼ tspSieve the corn flour and then mixwith coconut milk. Add sugar,coloring and salt. Mix well. Cookover stove, stirring continuouslyto prevent sticking for 45minutes. To test, spread a littleon a plate. Halwa should comeout clean and not stick to thefingers. Add cardamom & nutmegpowder & pour mixture into flattins. Sprinkle chopped dry fruitson top & cut into desired shapewhen cooled.Corn flour CoconutChocolate Halwa• Corn flour – 250g• Sugar – 400g• Coconut milk – 2 liters• Cocoa powder – 4 tbsp• Almonds & pistachios –1 tbsp each• Salt – ¼ tspFollow above directionssubstituting cocoa power forthe cardamom powder.ASIAN JEWISH LIFE ISSUE 1127

Featureby Gedaliah GurfeinNot Lost inTranslationA Torah scholargoes to ChinaASIAN JEWISH LIFE ISSUE 1129

Featureby Gedaliah GurfeinDuring my childhood growingup in New York I had heardabout China. Chinese foodon Sunday nights beforethe Ed Sullivan show was Torah fromMt. Sinai. Although I loved the food(especially the fortune cookies – I couldnever figure out how they knew muchabout us) the introduction to MSG left alot to be desired.There were always a couple of “Chinesekids” in school through the years; verysmart but somehow “different” morethan the rest of the “different” kids asif lost in an ancient world removed andmythical. In Junior High School mysocial studies report was on China.Tons of cut up National Geographic<strong>magazine</strong>s and anything else I couldpuzzle together went into the report. Ibecame fascinated with Mao Zedongand the struggle for change that theChinese people were going through.The Talmud says “there is no comparisonbetween (merely) hearing aboutsomething and (actually) seeing it.” SoI was left to but wonder each time wewent to New York’s Chinatown if Chinawas just like this but magnified a milliontimes over?It wouldn’t be for many years (about 40 tobe precise) that I would have the chanceto find out the answer. About five yearsago, work (in high tech) finally providedme the opportunity to go to China.All through the magic of email andSKYPE, I was now on an almost dailybasis in contact with D&B China,communicating, of course in English,but that kind of Chinese English Iremembered from Chinatown. Exceptthis time it wasn’t about ordering eggrolls it was about talking to peoplewhose brilliance shined. Sharp mindsand curious thinkers, opened mindedpeople with an excitement for life. Thesewere the Chinese? I was impressed,amazed and thankful to “discover”another intelligent ocean on a planetthat seemed to be drying up.My virtual image of China’s tipping pointto reality occurred as the Chinese NewYear arrived. My new Chinese “friends”told me they were going to tour Chinaand asked if I would I like to join. Wow!I had never been to China (although,when I was a <strong>Jewish</strong> teacher back inthe late 1980s I had lectured in HongKong) and here was a chance to seeChina through the eyes and minds of theChinese. I was there!Of course everywhere we went I feltlike “where is Waldo”. I thought it wascool, although my hosts were veryembarrassed, when they told me the localchildren were making fun of me calling me“round eyes”. I have Woody Allen blackrim round glasses. I’m sure for the kids itwas an even more exaggerated sight! Itbrought back shades of the book BlackLike Me and gave me my first feeling ofbeing a minority. Here “Chinatown” wasthe whole city with little pockets thatperhaps could be called “Western town”.The Chinese were awesome. It wasinstant love. In Shanghai I felt the sameenergy I remembered in my youth inNew York City during the “fun city” daysof Mayor Lindsay. It was alive, growingand nobody knows or knew where itwas heading – but who cared – the ridewas incredible. Even in Beijing whichhad a much more sedate nature to it, theForbidden City with Mao’s picture was asynapse between fantasy and reality. Imean when Mel Brooks said “It is good30 ASIAN JEWISH LIFE ISSUE 11

Featureby Gedaliah Gurfeinto be the King”, had he known about the3,000 wives (three times King Solomon’sharem) in the Imperial City, I’m sure hewould have corrected that to “it is goodto be the Emperor”. Personally I canconfirm that. When we made it to WestLake there was a tourist trap rentingEmperor clothing. I couldn’tresist and within seconds Ihad three wives! (Okay, at least3,000 is a multiple of three).Clearly the more important partof the trip was the exchange.There didn’t seem to be enoughhours in the day (or night) forthe dialogues, each wantingto know more and more aboutChina and the Jews. I hadnever thought about it before,until my new Chinese friendsbrought it to my attention, the<strong>Jewish</strong> impact on Chinese life.Beginning with Jesus, who Iquickly described as a distantcousin who had some “familyissues” and then to Karl Marx,whose grandfather was a greatrabbi and Kabbalist.From their perspective theywere most curious about theTalmud and Kabbalah. I toldthem the story that had justbroken before my trip in Israelwhere the Ambassador from SouthKorea announced at a meeting in TelAviv that “more children in Korea knowwho Rav Pappa is than in Israel.” Sadlyhe is correct, because anyone who hasstudied more than ten (daf) pages ofthe Talmud will have come across thename Rav Pappa. Now, Israel suddenlydiscovered that Koreans study theTalmud and within months Korean TVcrews were all over the Yeshivot (Talmudstudy schools) in Israel.They told me that the Talmud was alsonow becoming of interest in Chinaas the secret to <strong>Jewish</strong> success inbusiness. I agreed, quoting Rava fromthe Talmud that anyone who wishes tobecome smart should study the sectionof Talmud dealing with business law(Nezikim). I also told them I had beena Rabbi. I know, my friends always say“once you are a rabbi you are always arabbi” and I try to explain that was onlytrue of the Jets (not Jews) from WestSide Story. But I guess if it is in yourblood it is in your soul.So I began to share very deep ideasin <strong>Jewish</strong> thinking – why the moonwas smaller than the sun, what doesresurrection of the dead mean tomodern thinkers, and how much creamcheese must be applied to the bagelfor it to qualify as a shmear (smear).It was incredible to see these youngminds gobble up this information andretort with almost parallel teachingsfrom the East.Upon my return to Jerusalem I sent themtwo “Torah” books I had written, onecalled Good Morning, Moon and onecalled I Never Prayed for My Father. Iwas touched by the heartfelt feedbackboth positive and negative I received.Reminds me of a classic CharlieBrown cartoon where CharlieBrown is storming away fromLucy standing in her 5 centsPsychiatric box and she is yellingafter him, “The problem withyou, Charlie Brown, is you don’tknow how to handle destructivecriticism.” But I welcomed all ofit. I always remember my rebbeteaching me, “We have two earsand only one mouth becausewe need to listen twice as muchas we speak.” Considering Ilike to talk a lot I don’t know if Iever succeeded in following hisdictate but it has been somethingat least worth striving for.This story continues until aboutJune of this year when I wasblown away to find out myfriends had translated GoodMorning, Moon into Mandarin. Iwas so touched by this gesturethat I decided to give the bookaway for free as an eBook andhave posted the book on awebsite I helped to create for<strong>Jewish</strong> and Israeli books in general atwww.peopleoftheebooks.com and havewatched, in just a couple of months,an incredible number of the hits fromChina. These hits are not just comingin from the main cities but across thecountry. It has been forwarded byfriends, in China, as a gesture to helpbridge a better understanding of ourtwo cultures.The book is light on the heart and deepon the mind. I guess when you speakfrom the soul to the soul you can restassured the content will not get lost intranslation.ASIAN JEWISH LIFE ISSUE 1131

Viewpointby Tiberiu WeiszBiblical Influencein Chinese LiteratureWhat bound Judaism andChina into a seeminglyyin and yang culturalrelationship? The moreI research these two cultures, the morethey seemed to revolve around theperpetual changes created by yin andyang. Initially, I thought that the key mightlie in mastering the Chinese language.But, once I felt proficient in Chinese(I was already proficient in Hebrew) Irealized that even the two languageswere following the yin yang pattern. Bothlanguages are built on a similar system,the root words. Hebrew uses threeletters for the “root” called shoresh, whileChinese uses 214 basic “radicals” calledbushou. But the similarities in terms oflanguage end here.In Hebrew we form words by adding tothe “root” words either with declinationsof parts of speech or by conjugating theverbs in various tenses. Hebrew has acomplex grammar. In contrast, Chineseis a very simple language. It is basedon seven basic strokes to form 214“radicals” and a combination of radicalswith the basic strokes forms complexcharacters. For all practical purposes,Chinese has no grammar. And herein liesthe difficulty. While Hebrew grammar tellsus “who, what and when”, in Chinesewe have to deduce these questions fromthe context. Such ambiguity makes anyChinese text, especially ancient writings,very difficult to translate. Historically,Chinese characters changed meaningsignificantly during their long history andwhen reading Chinese texts one hasto know in what period of time it waswritten.32 ASIAN JEWISH LIFE ISSUE 11

Viewpointby Tiberiu WeiszIt is not surprising then, that Chineseand Israelites in antiquity did not haveanything in common and knew nothingabout each other’s culture. Israelitesmight have known about the “land ofSinim” from the Prophet Isaiah. But forthe Chinese, Israelites were just one ofthe unidentified tribes of the uncivilizedyi “barbarian” tribes. In biblical times,the Chinese called every non-Chinese“barbarians”. In this respect, they did notdistinguish between the Mongols or Hunraiders. Nor did they distinguish betweenthe peaceful tribes and settles, traders,and monks who occasionally intermixedwith the Chinese in the north and westof China. Chinese annals portrayedthe “barbarians” as raggedy looking,long red hair, dirty, unshaven and withrepulsive body odor.Yet, a sharp-eyed Chinese sage hadindeed described in one sentence a tribewith a strange custom. He talked abouta tribe that fasted, bathed and cleanedthemselves before praying to God. Thisdescription puzzled Chinese and Westernscholars alike. Who they were eludedan answer for a long time. It puzzledme too, but for a different reason. Thedescription seemed familiar, I just couldnot identify where I had seen that before.Only when I worked on the translation ofthe Kaifeng stone inscriptions and cameupon a similar Chinese sentence, did Irealize that those exact words originatedwith a very influential Chinese sage.Who was that sage?In my book The Kaifeng StoneInscriptions, I traced the journey of a groupof exiled Levites and Cohanim (priests)from Babylon (6th century BCE) to theKingdom of Ferghana (north Afghanistantoday) to the Western Regions andultimately their migration into China inthe second century BCE. The migrationfrom exile to the Western Regions tookperhaps as long as four hundred years.Of course, the exiles themselves werenot the original settlers in China but thedescendants of their descendants were.They were sighted at the outskirts ofChina in the second century BCE, andaccepted the Chinese offer to comeand settle in the Western Regions inreturn for the protection of the Chinese.The Western Regions (xiyu in Chinese)stretched from northern Afghanistan toDunhuang (the Pass in Chinese) in thenortheast of Gansu Province today. Hereended the main trade route, the so calledSilk Road that ran from Syria to CentralAsia, to Northern India, and to the WesternRegions. The Western Regions served asa buffer zone between China proper andthe Mongol/ Hun raiders who frequentlyinvaded and plundered China. To avertor minimize the impact of these raids, theChinese encouraged “barbarian” tribesto settle at the outskirts of China in theWestern Regions.We know very little about these Israeliteswho lived in the Western Regions, at theoutskirts of China for centuries. Mostof our information was based on whatthe Chinese Jews inscribed in stone.Amazingly, after many centuries inisolation, the Jews in China (Kaifeng) stillobserved the precepts of the Torah!Journeying in the vast desert land ofthe Western Regions, were two Chinesesages who had great influence on China.During their travels they might havecome in contact with Israelites, andonly a careful reading of their writinghinted at such an encounter. One of thesages was Mencius (372-289 BCE). Hisinfluence was second only to Confucius.His biography mentioned that late in hislife he left China and had spent twentyyears “beyond the Pass” in the WesternRegions. We know very little of hiswhereabouts or what he did. Most of theinformation is deduced from his writings.Apparently, he encountered a tribe duringhis journey that “fasted and bathed, andthen they sacrificed to Shangdi.” Shangdiwas the Chinese Almighty equal only toElohim. Mencius, like most Chinese ofhis time, did not have a high opinionof the “barbarians” and this tribe wasno exception. His exact words wererather unflattering. He said: “[If] Xizi hadbeen covered in such a filth [alternativetranslation: “with filthy head dress/clothes?], people would hold their noseswhen passing by. Although [those] peoplewere ugly, if they fasted and bathed, thenthey could sacrifice to Shangdi.“It is not coincidental that Mencius usedthe word xizi (pronounced shee-tze). Itmeans: “Son of the West.” And herelies the controversy. Who was Xizi? TheChinese suggested that it was the nameof Lady Xi. But Lady Xi was female andthe suffix zi (son, master) would indicatea male. The Chinese offered a simplesolution; they replaced the character ziwith the character shi (clan) thus clearingthe name for a female name. Thisexplanation is plausible, though I think it isfar fetched. Alternatively, Mencius mighthave used the word Xizi as a derogatoryterm for the tribe that fasted and purifiedthemselves before sacrificing to Shangdiin the Western Region.ASIAN JEWISH LIFE ISSUE 1133

Viewpointby Tiberiu WeiszIncidentally, the above descriptioncoincided with a biblical ceremonyperformed by the Levites (Numbers 8:21)and Cohanim (Leviticus 16:3-4) duringthe Temple period: “Wash yourselves,cleanse yourselves, put your evil deedsout of my sight!” before sacrificing.Reinforcing this commandment wasthe Prophet Isaiah (1:16) who remindedthe Levites and Cohanim to purify andcleanse themselves before makingtheir offerings to Elohim: “For this dayatonement shall be made for you tocleanse you, of all your sins before theLord. And when the priests and thepeople… hear the name of the Elohimcome from the mouth of the high priest,in sanctity and purity, they bow downand prostrate themselves.”Evidently during his travels to theWestern Region, Mencius came upona tribe that according to his descriptionfollowed almost identically the rites ofIsraelite priests. Perhaps this was thefirst sighting of Israelites in the vicinity ofChina as early as the 4th century BCE!Biblical Influence on DaoismWhile Mencius perhaps left us adescription of an Israelite tribe, anotherChinese sage had displayed biblicalinfluence in his writing. The legendaryLaozi (6th century BCE), the founder ofDaoism, better known in the West forhis mystical Book of the Way and Virtue(Daodejing) wrote about topics that wouldhad been more familiar to an Israelite thanto a Chinese person at that time.Laozi spent twenty years traveling inthe Western Regions. Legend says thatwhen he reached the Pass (Dunhuangtoday), Yinxi, the Keeper of the Pass,asked him to write a book. Evidently,Laozi obliged and wrote the Daodejinga five thousand-character book ofwisdom that rivals only the bible in itsdepth and wisdom. Whether or not thislegend is true is beside the point, whatis important is that the Daodejing hasgreatly impacted China. Even thoughit has been translated into almost everylanguage in the world, each translationis more of an interpretation than atranslation. The Daodejing is extremelydifficult to translate, if not impossible.Its language and concepts can be hardlymatched in any other language.Essentially, the Daodejing is full ofconcepts that would delight, and at thesame time challenge, any biblical scholar.They would have to face text like: “Daois [a] Dao but not [the] Dao, Name is [a]name, but not [the] Name… “ or : “Daois One…(we) see it, but it is unseen, itis called Invisible; (we) listen to it, but itis unhearable, it is called Inaudible; (we)touch it, but it is unreachable, it is calledIntangible”(ch. 14).A simple translation of Dao is the Way. Yet,we in the West have no single word that isequal to the Chinese Dao. Even thoughsome translators translated it as the Way,others as Heaven, and yet others as God,disappointingly, none of these terms isequal to the Chinese Dao. Invariably westill wrestle with the basic questions:What is Dao? Or, how did Laozi come upwith the idea of monotheism? Or, betteryet, where did Laozi hear about “the landof milk and honey”?I will focus on the last item. Daoism wasboth new and strange to the Chinese inthe 6th century BCE. At the time differentschools of thought fought for the mindof the people. There were so many ideasvying for followers, that the Chinesecalled them the “hundred schools”of thought. Most of these schoolsfaded from the Chinese mind and onlyDaoism and Confucianism prevailed.Confucianism dealt with government andethics; while the Daodejing dealt withmysticism, monotheism and one chapterdealt with, …well, nobody is sure.Unusual in style and content waschapter 80 of the Daodejing. Due to thelack of details about Laozi, both Chineseand Western historians thought that thischapter reflected his political ideology.Yet, it is not clear what his politicalphilosophy was, let alone the source ofthis chapter. We only know for a fact, thatthe conditions described in this chapterwere non-existent in China at the time.It described: “… a small country with fewpeople that makes weapons but do notuse them… Although they have ships andcarriages they do not ride them. Thoughthey have armor and soldiers, they donot display them… They sweetenedtheir food, adorned their clothes, werecontent in their homes and delighted intheir customs… people grew old anddied of old age.” In other words, Laozidescribed the Chinese version of the“land of milk and honey.”There is no doubt that Laozi had comein contact with “barbarian” tribes duringhis travels in the Western Region, wherehe might have heard stories of such acountry. He probably heard a story of a“land of milk and honey” (Exodus 33:3;Deut. 27:3) that in the Chinese versionin his book became a county wherepeople sweetened their food. Both milkand honey were luxuries for the few34 ASIAN JEWISH LIFE ISSUE 11

Interviewby Susan Blumberg-KasonInterview withHong Kong author Xu XiAuthor Xu Xi is Hong Kong’spreeminent writer in English.She has penned nine worksof fiction and essays,and has edited three anthologies ofHong Kong writing. Xu Xi received herMaster’s of Fine Arts in Fiction at theUniversity of Massachusetts at Amherst,and recently completed a three-yearchairmanship of Vermont College ofFine Art’s MFA program. Now back inher home city, she spends her days asWriter in Residence, City University ofHong Kong, where she founded the firstMFA program in Asia for English writers.<strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Jewish</strong> <strong>Life</strong> recently asked Xu Xiabout her <strong>Jewish</strong> characters, the futureof English literature in Hong Kong, andher writing career. She can be foundonline at www.xuxiwriter.com.<strong>Asian</strong> <strong>Jewish</strong> <strong>Life</strong> (<strong>AJL</strong>): In yourmost recent novel, Habit of a ForeignSky (Haven Books, 2010), which wasshortlisted for the 2007 inaugural Man<strong>Asian</strong> Literary Prize, two of the mostsympathetic characters have <strong>Jewish</strong>names. They both play large roles inthe development of the story. Did youintentionally choose identifiable <strong>Jewish</strong>names for these characters in honor ofpeople you know? Do <strong>Jewish</strong> charactersplay large roles in your other books also?Xu Xi (XX): I am so pleased you pickedup on the <strong>Jewish</strong> connection! That wasdeliberate on my part, not exactly inhonor of any particular individual but torecognize the American <strong>Jewish</strong> worldgenerally that I’ve come to know overthe years. It was noticeable to me thatmany of the Americans abroad in Asiawhom I met were <strong>Jewish</strong>, and it made merealize how much the diaspora Chineseand <strong>Jewish</strong> cultures had in common.Then later, living in New York City, Iagain met many <strong>Jewish</strong> people in theprofessional (and later literary as well)communities I was in (law especially),and the celebration of <strong>Jewish</strong> holidaysin New York made me more consciousof the culture and religion. I did alsodate a couple of <strong>Jewish</strong> guys back in mytwenties, and have had and of coursestill have a number of close <strong>Jewish</strong>friends. So yes I definitely did mean forboth Jim and Josh to be sympathetic.Actually, Jim first appeared in TheUnwalled City (2001) in a minor role andin my novel previous to that, Hong KongRose (1997), I had an American in HongASIAN JEWISH LIFE ISSUE 1137

Interviewby Susan Blumberg-KasonKong named Elliott Cohen who hada major role in the story. Elliott was apretty sympathetic character as well. Soas you can see <strong>Jewish</strong> characters haveappeared for some time in my work.<strong>AJL</strong>: Your family hails from Indonesia,where the Chinese community hassuffered terribly. Do you find an affinitywith Jews due to a shared backgroundof persecution based solely on ethnicity,or otherness?XX: I have mixed feelings about thenotion of “persecution” of the Chinesecommunity in Indonesia. Yes, theoverseas Chinese were definitelypersecuted – this is a historicalfact. Yet having grown up listeningto the prejudiced way many in myfamily spoke about the Indonesians– they unabashedly looked down onIndonesians, calling them stupid andlazy – that gave me a sense of whythe Indonesians might have hatedthe Chinese. I recall as a child feelingashamed of my family’s attitudesand prejudices and rebelled as I gotolder. The Chinese community valuededucation and were ambitious interms of trying to build a good life forthemselves and their families – thiswas certainly true in both my parents’family. And this probably gave rise toenvy by a local population that watchedthese immigrants move in, take over,and boss them around. In a way, it’sthe immigrant story the world over andthere’s no simple way to parse it and saywe were right they were wrong becauseit’s never that simple.<strong>AJL</strong>: For much of your adult life, youjuggled a corporate day job with writingin your spare time. How did you decideto leave the corporate world so youcould devote all your time to writing?XX: The Peter Principle. I’d risen to mylevel of incompetence in corporate lifeand had lost interest, frankly, in climbingany further up the ladder. Most of thetime, I enjoyed my work in the variouscorporations I worked for, and wasambitious and sought better prospectsand promotions. But by the time mythird book was published, I no longerwas as interested in making my markin corporate life and could tell that if Ihung on, just to have a job, I’d begin adownslide which wouldn’t be good forme or my employer. It was beginning tofeel too schizophrenic.As fate would have it, my aunt passedaway which was very sad, becauseshe was someone my family was veryclose to. She surprised my family withher wealth and I ended up with thisinheritance (she was a schoolteacherwho lived frugally, saved a bundle,invested smart and died a very, very richlady). So I knew that as long as I didn’texpect to live as I used to when I had afull-time salary, I would be just fine. AndI was fine for many years, picking up alittle part time work, later some part timeteaching, and all through this I tradedstocks & futures to stay afloat (that wasquite a lot of fun, I found). And writing,writing, writing. It was a fabulous life.So it was a decision facilitated byan unexpected inheritance windfall,Xu Xibecause it was as if my aunt were tellingme – here, go live your real life, go.<strong>AJL</strong>: Several years ago, you edited ananthology titled, Fifty-Fifty: New HongKong Writing (Haven Books, 2008),which addressed the years leadingup to the year 2046, when China’sone country, two systems policy ofgoverning Hong Kong is due to expire.What are your views on the future ofEnglish literature produced in HongKong in the years leading up to thisnext handover?XX: Ask me next year and I’ll havemore views because I’m currently coeditinganother anthology of new HongKong short fiction for CCC Press in theU.K. There’s more literature in Englishthese days, although I must admit I’mnot wildly optimistic about the future ofthis literature. As Hong Kong becomesmore Chinese, it may lose some ofits international edge. The Englishliterature from this city has always beena marginalized and marginal literature,and I’m not seeing much by way ofemerging younger writers because theones with talent get sidetracked by themoney culture and societal pressures todo something “practical,” which writingisn’t (although from my standpoint,38 ASIAN JEWISH LIFE ISSUE 11

Interviewby Susan Blumberg-Kasonwhat could be more practical thantrying to understand your raison d’etre,which is what all serious writers arebasically doing). Much will depend onthe Hong Kong’s government, if it canprovide any kind of visionary leadershipthat allows one country two systemsto flourish. But from my perspective,I do feel like I’m watching one countrytwo systems languish. I’m just hopingit won’t fizzle out and die, because thatwill be the end of Hong Kong as anykind of international city.<strong>AJL</strong>: Over the years you have beenpublished by several independentpresses in Hong Kong. Can you discussyour experience with Hong Kongpublishers and what you see as thefuture of small presses?XX: I’m actually very optimistic aboutthe future of small presses, both herein Hong Kong and the U.S. This largelyhas to do with the major publishersabandoning any kind of literary vision(except for a very small part of theirbusiness) in favor of producing booksas a form of celebrity merchandise.Let’s face it, if you’re sports star ormovie star or someone who becamefamous for five seconds for somenotoriety (Monica Lewinsky is a goodexample), you can be an “author”without having to be a writer, we allknow that. This may be profitable forso-called publishers, but is extremelydestructive to contemporary literaryculture. Lewinsky signed a hell of a lotmore books than I and most writers Iknow ever will! Meanwhile the midlistno longer exists. But what I do see area lot of small presses picking up thepieces for the major publishers whohave abandoned their original calling.<strong>AJL</strong>: Can you share a little of what you’reworking on now? In the future?XX: Sure. I recently finished a newnovel which my agent is shoppingaround at the moment. The book tookme nine years to complete, what witheverything else I was doing (and I didpublish two books during that time), soI think I’m suffering from a kind of novelfatigue. In the past I always was into anew novel once I finish one. I did start anew novel but almost immediately putit aside in favor a novella, short storiesand essays.ASIAN JEWISH LIFE ISSUE 1139

BookReviewsby Susan Blumberg-KasonVoices from ShanghaiSephardic and Ashkenazi Families during WWIIDuring World War II, Shanghai was home to the largest and mostdiverse <strong>Jewish</strong> community in China. The Sephardic familiesfrom Baghdad and Bombay were the most prosperous andenjoyed the longest history among the Jews in Shanghai.Ellis Jacob came from one such family. Several years agohe wrote The Shanghai I Knew: A Foreign Native in Pre-Revolutionary China (Comteq Publishing, 2007), a memoirof his formative years in the city on the sea.Ellis Jacob ties his family’s story in with the modernhistory of China. Although he writes that the Jewsand Chinese didn’t mix much socially, his familyhad Chinese servants and as a result he learnedto speak Shanghainese, the local dialect. Hesprinkles bits of Shanghainese throughout hismemoir, and tells the story of an Americansolider who hires him to be his translator whilehe visits a brothel. At the time, Jacob was tooyoung to understand just what kind of anestablishment the American had taken him.His family held British citizenship (mostSephardic Jews in Shanghai did) and arrived before1937, they were not sent to the Shanghai Ghetto when otherJews were in 1942. But he wrote about the food shortagesand political instability during that time. Ellis Jacob attendeda British elementary school and an American high school.During the thick of the war, most schools closed. He wasfortunate to transfer to the Shanghai <strong>Jewish</strong> School for a year,which stayed open.In the appendix, Jacob includes images of money from themid-to-late 1940s, family photos, and menus from ice creamparlors. Inflation ran wild after the war, and people had nochoice but to carry their cash in suitcases. All that cash couldonly buy one ice cream sundae or a loaf of bread. He pointsout that the menus were continuously changed to account fordaily changes in inflation.When Ellis Jacob and his mother left Shanghai for Canada,he almost wasn’t allowed on the ship, as there was someconfusion over a debt that a different Ellis Jacob owed. Withhis father’s quick thinking, teenage Ellis Jacob was allowedto depart as scheduled. Interestingly, only Jacob and hismother left on that ship; his father remained in Shanghai tofinish business matters. He ends his memoir before the timehis father was supposed to leave China, so the reader neverknows what happened to the senior Jacob.Another memoir from this period, written by a woman whoseAustrian <strong>Jewish</strong> family had escaped to Shanghai, is Ten GreenBottles: The True Story of One Family’s Journey from War-tornAustria to the Ghettos of Shanghai (St. Martins, 2004) by VivianJeanette Kaplan. The author’s family belonged to the largestgroup of Jews in Shanghai during the war: the European <strong>Jewish</strong>refugees from Austria and Germany. Kaplan writes from thepoint of view of hermother, Nini, because young Vivian was justa baby when the family left Shanghai for Canada after the war.Nini Karpel meets her husband-to-be in hermother’s Vienna dress shop. Leopold, or Poldias he’s known, came from Poland and told of thepersecution of the Jews. Nini couldn’t imagine lifewould ever change for her family in Vienna becausethe Jews were assimilated into Austrian life. But ashistory would show, life did change for the Jewsthere. By the late 1930s, many found themselvesdesperate to leave. Emigrating to the US, Canada,and Great Britain were not usually viable options.As Kaplan writes, word about Shanghai spreadthough Vienna:In our quest for options, one word is beginning to recur:“Shanghai.” We hear it whispered behind cupped hands whenwe pass haggard neighbours on the streets. News travels ina human telegraph line from one to the next. “Shanghai,” theysay, the strange word pronounced with an Austrian accent,odd, exotic, remote, spoken with fear and hope, the onlypossibility.It is not without misfortune and anxiety that Nini and Poldi endup in Shanghai, Nini arriving first with her parents. Throughthe eyes of her mother, Kaplan so vividly describes Shanghaiduring the war: the grime, the excesses, the noises, and thesmells. Nini finds a hostess job in the famous Bolero Club,where “glamorous women and powerful men mesh in a kind ofdream world, like a scene from a motion picture.”The couple marries at Ohel Moishe, one of seven synagoguesin Shanghai. Later Nini and Poldi go in with a Bulgarian Jewto run Marco’s Bar, a dive establishment frequented by someof Shanghai’s lowliest expats. <strong>Life</strong> for the Jews in Shanghaichanges at the end of 1941 when the Japanese occupy thecity. Ellis Jacob discusses the changes during the occupation,but families like Nini and Poldi’s feel the effects of starvationmore than those in the Sephardic community. To make endsmeet, Poldi devises a plan to obtain American dollars fromHarbin in northeast China, also home to a sizeable <strong>Jewish</strong>community. He and Nini risk their lives to travel up to Harbinand to Japan to trade goods for dollars.Just like Ellis Jacob and his family, Nini, Poldi, and baby Vivian— along with other family members — emigrate to Canada in1949, before the Communist revolution.These memoirs show the diverse experiences of Jews inShanghai during the war. While these families came fromdifferent backgrounds, they experience similar hardshipsduring the war and all end up immigrating to Canada tostart afresh.40 ASIAN JEWISH LIFE ISSUE 11

HOME AWAY FROM HOMEThe Star That MakesWishes Come TrueWhen you fly EL AL to Israel, you get there faster.As soon as you board the plane, you’re surrounded by an atmospherethat’s uniquely Israeli. Warmth, friendliness, bagels-for-breakfastand welcome-home feeling. EL AL - simply the best way to catchthe Israeli spirit even before you arrive.