Switching Costs in Two-sided Markets - Ecares

Switching Costs in Two-sided Markets - Ecares

Switching Costs in Two-sided Markets - Ecares

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

This equation shows that the number of agents from side i belong<strong>in</strong>g to platform 0 <strong>in</strong> thesecond period is the sum of three terms. The first element represents with probability µ ithe old customers are loyal. The second and third terms represent with probability 1−µ ithe old customers are switchers (whose preferences are unrelated <strong>in</strong> the two periods):they can either be switchers who did not switch away from platform 0 or switchers whoactually switched from platform 1 to platform 0.Then solv<strong>in</strong>g for n A 0,2 and nB 0,2 simultaneously, we obta<strong>in</strong> the second-period marketshares of groups A and B as follows:wheren i 0,2 = γ + β i + (1 − µ i )(p i 1,2 − pi 0,2 ) + e i(1 − µ i )(1 − µ j )(p j 1,2 − pj 0,2 ),2γγ =1 − (1 − µ A )(1 − µ B )e A e B ,β i =(2n i 0,1 − 1)(µ i + (1 − µ i )s i ) + (2n j 0,1 − 1)(1 − µ i)e i (µ j + (1 − µ j )s j ).S<strong>in</strong>ce I have assumed at the beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g that e i < 1, so γ > 0.The respective second-period profit of platforms 0 and 1 can be written as:π 0,2 = p A 0,2n A 0,2 + p B 0,2n B 0,2,π 1,2 = p A 1,2(1 − n A 0,2) + p B 1,2(1 − n B 0,2).Substitute n A 0,2 (pA 0,2 , pA 1,2 , pB 0,2 , pB 1,2 ) and nB 0,2 (pA 0,2 , pA 1,2 , pB 0,2 , pB 1,2 ) <strong>in</strong>to these two profit functions.Then, by differentiat<strong>in</strong>g π 0,2 with respect to p A 0,2 and pB 0,2 , and differentiat<strong>in</strong>g π 1,2with respect to p A 1,2 and pB 1,2 , we obta<strong>in</strong> 4 equations and 4 unknowns.∂π 0,2∂p i 0,2∂π 1,2∂p i 1,2= n i 0,2 − pi 0,22γ (1 − µ i) − pj 0,22γ e j(1 − µ i )(1 − µ j ),= 1 − n i 0,2 − pi 1,22γ (1 − µ i) − pj 1,22γ e j(1 − µ i )(1 − µ j ).Solv<strong>in</strong>g the system of first-order conditions, one f<strong>in</strong>ds the follow<strong>in</strong>g four second-periodequilibrium prices.wherep i 0,2 = 1 − e j(1 − µ i )1 − µ i+ η iλ i + ɛ i λ j(1 − µ i )∆ , (1)p i 1,2 = 1 − e j(1 − µ i )1 − µ i− η iλ i + ɛ i λ j(1 − µ i )∆ . (2)∆ = 9 − (1 − µ A )(1 − µ B )(e A + 2e B )(e B + 2e A ) > 0,λ i = (2n i 0,1 − 1)(µ i + (1 − µ i )s i ),η i = 3 − e j (e j + 2e i )(1 − µ i )(1 − µ j ) > 0,ɛ i = (1 − µ i )(e i − e j ).6

Corollary 2. In the mature market, the equilibrium profits of the two platforms can bea decreas<strong>in</strong>g function of switch<strong>in</strong>g costs under the follow<strong>in</strong>g conditions:∂π 0,2∂s i< 0when µ i is small, µ j is large, e i > e j , and n i 0,1 > 1 2 .Corollary 2 is a special case of Proposition 3, which shows that the second-periodequilibrium profits can be decreas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the switch<strong>in</strong>g costs for some values of loyalty,network externality, and market shares.2.2 First Period: the new marketI now turn to exam<strong>in</strong>e the equilibrium outcomes <strong>in</strong> the first period where consumers arenot attached to any platform. Recall that on side i, a proportion α i of the consumersare naive (N). S<strong>in</strong>ce they care only about today, they have δ i = 0. On the contrary, aproportion 1 − α i of side-i’s population is rational (R). S<strong>in</strong>ce they fully anticipate the<strong>in</strong>fluence of their first-period decisions on the second period, they have δ i > 0.A naive consumer of side i is <strong>in</strong>different between buy<strong>in</strong>g from platform 0 and platform1 ifv i + e i n j 0,1 − x − pi 0,1 = v i + e i (1 − n j 0,1 ) − (1 − x) − pi 1,1,which can be simplified tox = 1 2 + 1 2 [e i(2n j 0,1 − 1) + pi 1,1 − p i 0,1] = θ i N.A sophisticated consumer of side i is <strong>in</strong>different between purchas<strong>in</strong>g from platform 0and platform 1 ifv i + e i n j 0,1 − x − pi 0,1 + δ i U i 0,2 = v i + e i (1 − n j 0,1 ) − (1 − x) − pi 1,1 + δ i U i 1,2.After some rearrangement, this givesx = 1 2 + 1 2 [e i(2n j 0,1 − 1) + pi 1,1 − p i 0,1 + δ i (U i 0,2 − U i 1,2)] = θ i R,where U0,2 i and U 1,2 i are the respective expected utilities that a side-i agent obta<strong>in</strong>s fromjo<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g platforms 0 and 1 <strong>in</strong> the second period, and are def<strong>in</strong>ed as follows.U i 0,2 =µ i (v i + e i n j 0,2 − x − pi 0,2) + (1 − µ i )θ i 0|0 (v i + e i n j 0,2 − x − pi 0,2)+ (1 − µ i )(1 − θ i 0|0 )(v i + e i (1 − n j 0,2 ) − (1 − x) − pi 1,2 − s i ).U0,2 i is the sum of three terms. It shows that with probability µ i the consumer is loyaland chooses to jo<strong>in</strong> platform 0 <strong>in</strong> both periods, with probability (1 − µ i )θ0|0 i he has9

Consider the symmetric equilibrium such that p A 0,1 = pA 1,1 and pB 0,1 = pB 1,1 , so thatn A 0,1 = nB 0,1 = 1 2 (hence λ i = 0). Then, we simplify the first-order conditions and solvesimultaneously for p A 0,1 and pB 0,1 .p i 0,1 = 1 − κ iτ i− σ jτ j− e j − δ F ξ i .The discussion is summarized <strong>in</strong> the follow<strong>in</strong>g proposition.Proposition 4. The two-period two-<strong>sided</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gle-hom<strong>in</strong>g duopoly model, where on eachside a proportion α i of the consumers are naive while the rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g consumers aresophisticated, and a fraction µ i of the consumers have fixed preferences while the othershave <strong>in</strong>dependent preference, has a symmetric equilibrium. The first-period equilibriumprices for group A and group B are given respectively byp A 0,1 = 1 − κ Aτ A− σ Bτ B− e B − δ F ξ A ;p B 0,1 = 1 − κ Bτ B− σ Aτ A− e A − δ F ξ B , (3)and <strong>in</strong> the second period, each platform’s equilibrium pric<strong>in</strong>g strategies are given byp A 0,2 = 1 − e B(1 − µ A )1 − µ A; p B 0,2 = 1 − e A(1 − µ B )1 − µ B.In equilibrium, the second-period pric<strong>in</strong>g strategies is computed by substitut<strong>in</strong>g symmetricmarket shares <strong>in</strong>to Equations (1) and (2).3 DiscussionThe analysis of the effect of switch<strong>in</strong>g costs on first-period prices is complicated asp A 0,1 and pB 0,1 are long expressions with many variables. An easier way to <strong>in</strong>terpret theresults is to start the discussion from pure switch<strong>in</strong>g-cost model (à la Klemperer) andpure two-<strong>sided</strong> model (à la Armstrong), and then extend to mixed models with different<strong>in</strong>gredients.3.1 Pure <strong>Switch<strong>in</strong>g</strong>-cost ModelIn the simplest two-period model of switch<strong>in</strong>g costs with two symmetric firms, zeromarg<strong>in</strong>al costs, and undifferentiated competition, the firms know<strong>in</strong>g that they can exerciseits ex post market power <strong>in</strong> the second period over those consumers who are locked-<strong>in</strong>(p 2 = s), they are will<strong>in</strong>g to price below cost (p 1 = −δs) <strong>in</strong> the first period to acquirethese valuable customers. Consumers foresee<strong>in</strong>g the possibility of be<strong>in</strong>g exploited <strong>in</strong>the future will become more <strong>in</strong>different between the two compet<strong>in</strong>g firms, and the onlyth<strong>in</strong>g that matters to them is today’s price. This implies that even rational consumersbehave <strong>in</strong> a naive way, and this is equivalent to sett<strong>in</strong>g δ i , α i = 0 <strong>in</strong> the current model. 44 Note that one can <strong>in</strong>terpret δ i(1 − α i) as a measure of rationality <strong>in</strong> the current analysis.11

Moreover, µ i , e i = 0 because <strong>in</strong> this simple switch<strong>in</strong>g-cost model consumer’s loyalty andnetwork externality do not matter.Together, Equation (3) is simplified toThis implies thatp i 0,1 = 1 − 2 3 δ F s i∂p i 0,1∂s i< 0.This pattern of attractive <strong>in</strong>troductory offers followed by higher prices to exploit locked<strong>in</strong>customers (proved <strong>in</strong> Proposition 1) is well-known from the switch<strong>in</strong>g-cost literature.3.2 Pure <strong>Two</strong>-<strong>sided</strong> ModelIn a simple model of two-<strong>sided</strong> markets, there is only one period so that δ F , δ i , α i = 0,and loyalty and switch<strong>in</strong>g costs are irrelevant (s i , µ i = 0). Then, τ i = 1, κ i , σ i , ξ i = 0,and Equation (3) is reduced top i = 1 − e j ,which is exactly the unique symmetric equilibrium <strong>in</strong> the two-<strong>sided</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gle-hom<strong>in</strong>g model<strong>in</strong> Proposition 2 of Armstrong (2006). 5 The <strong>in</strong>terpretation of this condition is that theside of the market which exerts a larger external benefit on the other side tends to facelower prices.3.3 <strong>Switch<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Costs</strong>, <strong>Two</strong>-<strong>sided</strong> <strong>Markets</strong> and NaiveteSuppose that all consumers are myopic such that δ i , α i = 0. For conciseness, assumepreferences <strong>in</strong> the two periods are unrelated (µ i = 0). Then, we are left with s i , e i , δ F > 0.Equation (3) becomesp i 0,1 = 1 − δ F[ 6∆ + e i − e j − (e i + e j )(e j + 2e i )∆]s i − e j .S<strong>in</strong>ce the term <strong>in</strong> the square brackets (denoted as ζ henceforth) is positive, this gives∂p i 0,1∂s i< 0.5 S<strong>in</strong>ce Armstrong’s model is of one period only, we can replicate his result by sett<strong>in</strong>g s i, µ i = 0 <strong>in</strong>the second-period equilibrium prices or with first-period equilibrium prices by tak<strong>in</strong>g away the effect offirst period on the second period.12

3.4 <strong>Switch<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Costs</strong>, One-<strong>sided</strong> <strong>Markets</strong> and RationalitySuppose that all consumers and the two platforms are rational such that δ i , δ F > 0 andα i = 0. e i = 0 s<strong>in</strong>ce there is no two-<strong>sided</strong>ness. For simplicity, assume that consumersdraw new preferences <strong>in</strong> each period (µ i = 0). Equation (3) can be simplified top i 0,1 = 1 + δ i s i + 4 3 δ is 2 i − 2 3 δ F s i .Differentiat<strong>in</strong>g p i 0,1 with respect to s i, we obta<strong>in</strong>Lemma 1. In the two-period s<strong>in</strong>gle-hom<strong>in</strong>g duopoly model, where network externality isabsent, all consumers are rational, and their preferences are <strong>in</strong>dependent over time,i. If consumers are relatively less patient than the platforms, then the relationshipbetween first-period equilibrium prices and switch<strong>in</strong>g costs is U-shaped.ii. If consumers are relatively more patient than the platforms, then first-period equilibriumprices always <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> switch<strong>in</strong>g costs.See Appendix B for the proof.3.5 <strong>Switch<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Costs</strong>, <strong>Two</strong>-<strong>sided</strong> <strong>Markets</strong> and RationalityThe prelim<strong>in</strong>aries are the same as the previous case, δ i , δ F , s i > 0 and α i , µ i = 0, exceptthat the market is two-<strong>sided</strong> now (e i > 0). In this case, Equation (3) can be rewrittenasp i 2(3 − ∆)0,1 = 1 + δ i s i −∆δ is 2 i − 2δ j∆ (e j + 2e i )s j s i − δ F ζs i − e j .Differentiat<strong>in</strong>g p i 0,1 with respect to s i, we obta<strong>in</strong>Lemma 2. In the two-period two-<strong>sided</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gle-hom<strong>in</strong>g duopoly model, where all consumersare rational, both groups of consumers have switch<strong>in</strong>g costs, each side exerts thesame external benefit on the other side, and their preferences are <strong>in</strong>dependent over time,i. For sufficiently weak externality,• If consumers are relatively less patient than the platforms, then the relationshipbetween first-period equilibrium prices and switch<strong>in</strong>g costs is U-shaped.• If consumers are relatively more patient than the platforms, then first-periodequilibrium prices always <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> switch<strong>in</strong>g costs.ii. For sufficiently strong externality,• If consumers are relatively less patient than the platforms, then first-periodequilibrium prices always decrease <strong>in</strong> switch<strong>in</strong>g costs.13

• If consumers are relatively more patient than the platforms, then the relationshipbetween first-period equilibrium prices and switch<strong>in</strong>g costs is <strong>in</strong>vertedU-shaped.See Appendix C for the proof.Collect<strong>in</strong>g Lemmas 1 and 2 we obta<strong>in</strong> the follow<strong>in</strong>g proposition.Proposition 5. In the two-period two-<strong>sided</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gle-hom<strong>in</strong>g duopoly model, where allconsumers are either naive or sophisticated, and their preferences are <strong>in</strong>dependent overtime,i. If all consumers are sufficiently naive, then first-period equilibrium prices are decreas<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> switch<strong>in</strong>g costs.ii. The presence of strong network externality makes it more likely that switch<strong>in</strong>g costswill lower the first-period equilibrium prices.Proof. Immediate from Lemmas 1 and 2.The <strong>in</strong>tuition underly<strong>in</strong>g this proposition is as follows. (i) When consumers aremyopic, they would not anticipate that a discounted price today presages a higher pricetomorrow, and hence will react more responsively to price cut <strong>in</strong> the first period. Thus,platforms have more <strong>in</strong>centive to charge a lower price to them. The higher the switch<strong>in</strong>gcosts they <strong>in</strong>cur, the lower the price is, s<strong>in</strong>ce platforms can earn more by milk<strong>in</strong>g thehigh switch<strong>in</strong>g costs customers <strong>in</strong> the subsequent period. 6 (ii) Cross-group externalitiesprovide additional <strong>in</strong>centive for platforms to compete hard for the high-externality group.From Lemma 2, we have the follow<strong>in</strong>g corollary:Corollary 3. In the two-period two-<strong>sided</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gle-hom<strong>in</strong>g duopoly model, where all consumersare rational, and their preferences are <strong>in</strong>dependent over time, as the switch<strong>in</strong>gcosts of side-j consumers <strong>in</strong>crease, it is more likely that the first-period equilibrium pricespaid by side-i consumers decrease <strong>in</strong> the switch<strong>in</strong>g costs of side i.The <strong>in</strong>tuition beh<strong>in</strong>d this corollary is as follows. First, rational consumers are lesssensitive to price cuts because they understand that a low price today will result <strong>in</strong> ahigher price tomorrow. Second, it is even more difficult for the platforms to attract thegroup of consumers who bear higher switch<strong>in</strong>g costs because it requires a larger pricecut <strong>in</strong> order to capture them. For these two reasons, the competitive pressure is shiftedto the group with lower switch<strong>in</strong>g costs <strong>in</strong>stead, and this leads to lower prices be<strong>in</strong>gcharged to this group.6 Broadly speak<strong>in</strong>g, f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g (i) is <strong>in</strong> l<strong>in</strong>e with most of the literature on the effect of consumers’ expectationsabout future prices on the relationship between switch<strong>in</strong>g costs and prices. For example,von Weizsäcker (1984) shows that if consumers expect that a firm’s price cut is more permanent thantheir tastes (which can be <strong>in</strong>terpreted as naive consumers), then switch<strong>in</strong>g costs tend to lower prices.However, the <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g twist here is to exam<strong>in</strong>e the effect of switch<strong>in</strong>g costs on the pattern of prices <strong>in</strong>two-<strong>sided</strong> markets, where externalities are also present.14

3.6 Heterogeneous ConsumersI now turn to discuss, rather than hav<strong>in</strong>g all consumers be<strong>in</strong>g rational or be<strong>in</strong>g naive,the consequences of hav<strong>in</strong>g heterogeneous consumers on each side, where a proportion α iof side-i consumers are myopic, while 1−α i of them are forward-look<strong>in</strong>g. Differentiat<strong>in</strong>gEquation (3) with respect to α i , α j and δ F , we obta<strong>in</strong> the follow<strong>in</strong>g:Proposition 6. In the two-period two-<strong>sided</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gle-hom<strong>in</strong>g duopoly model, where oneach side a fraction α i of the consumers are naive, while 1 − α i of them are rational; µ iconsumers are loyal, while the rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g ones have <strong>in</strong>dependent preferences,i. p i 0,1 is decreas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> α i if µ i is close to 1.ii. p i 0,1 is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> α j.iii. p i 0,1 is decreas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> δ F .See Appendix D for the proof.The <strong>in</strong>tuition beh<strong>in</strong>d this proposition is as follows. (i) shows that hav<strong>in</strong>g morenaive consumers on one side lowers the price of this side if this side conta<strong>in</strong>s manyloyal consumers. The reason for this is that when all consumers of this side are loyal(µ i = 1), they know that once they have purchased they will be locked-<strong>in</strong> with thesame platform forever, and thus have to be offered a bigger carrot <strong>in</strong> the first period.Moreover, naive consumers, who care only about today, are more attracted by a currentprice cut. Therefore, an <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> loyal and naive consumers provides more <strong>in</strong>centivesfor platforms to compete aggressively. (ii) shows that hav<strong>in</strong>g more naive consumers onone side will <strong>in</strong>crease the price of the other side. Intuitively, smaller marg<strong>in</strong>s to conv<strong>in</strong>cethe myopic consumers on one side to jo<strong>in</strong> the platform must be recouped through largermarg<strong>in</strong>s on the other side. This type of unbalanced price structure is common <strong>in</strong> two<strong>sided</strong>markets. (iii) <strong>in</strong>dicates that equilibrium prices are lower when the platforms aremore patient. The <strong>in</strong>tuition is that firms compete harder on prices because they foreseethe advantage of hav<strong>in</strong>g a large customer base <strong>in</strong> the next period.3.7 Effect of switch<strong>in</strong>g costs on first-period profitIn equilibrium,π 0 = 1 2 pA 0,1 + 1 2 pB 0,1 + δπ 0,2 .Thus,∂π 0= 1 ∂p A 0,1+ 1 ∂p B 0,1∂s i 2 ∂s i 2 ∂s ibecause π 0,2 are not affected by s i <strong>in</strong> equilibrium.As is well-known from the switch<strong>in</strong>g-cost literature, switch<strong>in</strong>g costs raise platforms’profits <strong>in</strong> the second period as prices are usually higher. However, the presence of marketpower over the locked-<strong>in</strong> consumers <strong>in</strong>tensifies competition <strong>in</strong> the first period, and this15

may result <strong>in</strong> a decrease <strong>in</strong> overall profit as switch<strong>in</strong>g costs <strong>in</strong>crease. 7 More <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>gis that here identifies additional channels which may make overall profit decreases <strong>in</strong>switch<strong>in</strong>g costs. In particular, network externality and naivete make it more likely thatswitch<strong>in</strong>g costs lower first-period equilibrium prices, and hence reduc<strong>in</strong>g overall profits.4 ExtensionsThe analysis so far is based on a s<strong>in</strong>gle-hom<strong>in</strong>g model, but this is not the only marketconfiguration <strong>in</strong> reality. There are various ways to extend the model, for <strong>in</strong>stance, onemay consider the case where one group s<strong>in</strong>gle-homes while the other group may jo<strong>in</strong> eitherone platform or both (commonly termed as “competitive bottlenecks” because eachplatform has exclusive market power over the multi-hom<strong>in</strong>g consumers), the two groupsof consumers bear different switch<strong>in</strong>g costs, and the two platforms are asymmetric. I willsketch these extensions <strong>in</strong> turn, but leave the full-scale analysis of them for a separatestudy.4.1 Competitive BottlenecksSuppose that side A cont<strong>in</strong>ues to s<strong>in</strong>gle-home, while side B may multi-home (or not). 8Competitive bottleneck framework is typical <strong>in</strong>, for <strong>in</strong>stance, the computer operat<strong>in</strong>gsystem market (users use a s<strong>in</strong>gle OS, W<strong>in</strong>dows, Mac or L<strong>in</strong>ux, while eng<strong>in</strong>eers developsoftware for different OS), and onl<strong>in</strong>e air ticket or hotel book<strong>in</strong>gs (consumers use onecomparison site such as skyscanner.com, lastm<strong>in</strong>ute.com or book<strong>in</strong>g.com, but airl<strong>in</strong>esand hotels jo<strong>in</strong> multiple platforms <strong>in</strong> order to ga<strong>in</strong> access to each comparison site’sconsumers). S<strong>in</strong>ce side B can choose both platforms, switch<strong>in</strong>g costs and loyalty onthis side are not relevant (s B , µ B = 0). 9 The ma<strong>in</strong> difference from the s<strong>in</strong>gle-hom<strong>in</strong>gmodel lies <strong>in</strong> the market share of side-B consumers, which can be described as follows.A consumer from this group is <strong>in</strong>different between buy<strong>in</strong>g and not buy<strong>in</strong>g from platform0 ifv B + e B n A 0,2 − x − p B 0,2 = 0,which can be simplified ton B 0,2 = x = v B + e B n A 0,2 − p B 0,2.7 See for <strong>in</strong>stance Klemperer (1987a).8 Side B does not necessarily universally multi-home.9 Note that the concept of multi-hom<strong>in</strong>g is not compatible with switch<strong>in</strong>g costs <strong>in</strong> the current framework.As an example, th<strong>in</strong>k of the smartphone market. If the option to multi-home means consumersare able to use both iPhone and Android systems, then it is not reasonable to impose an additionallearn<strong>in</strong>g cost on them if they switch platform. Another example is the media market. If multi-hom<strong>in</strong>gmeans that advertisers are free to put ads on platform A, B or both, then it does not make sense toimpose a switch<strong>in</strong>g cost on advertisers who buy ads on one platform only. Even if we dist<strong>in</strong>guish betweenlearn<strong>in</strong>g switch<strong>in</strong>g costs (<strong>in</strong>curred only at a switch to a new supplier) and transactional switch<strong>in</strong>g costs(<strong>in</strong>curred at every switch), as <strong>in</strong> Nilssen (1992), switch<strong>in</strong>g cost is still not relevant on the multi-hom<strong>in</strong>gside because transaction costs and learn<strong>in</strong>g costs are equivalent <strong>in</strong> a two-period model, where consumersswitch only once. This also expla<strong>in</strong>s why it is not useful to consider the case where both sides multi-homewith<strong>in</strong> this framework.16

Similarly, a side-B consumer is <strong>in</strong>different between buy<strong>in</strong>g and not buy<strong>in</strong>g from platform1 ifv B + e B (1 − n A 0,2) − (1 − x) − p B 1,2 = 0,which can be reduced ton B 1,2 = 1 − x = v B + e B (1 − n A 0,2) − p B 1,2.We solve the game by backward <strong>in</strong>duction as before. To simplify the exposition, wefocus on the special case where e A = e B = e, µ A = 0, and δ A = δ B = δ F = δ. Considerthe symmetric equilibrium. We f<strong>in</strong>d the follow<strong>in</strong>g first-period equilibrium prices:p A 0,1 =1 + δs A3 − e2 − v B2 − 2δs2 A (3e2 − 2)3(1 − e 2 ,)p B 0,1 = v B2 .Differentiat<strong>in</strong>g p A 0,1 with respect to s A, we obta<strong>in</strong>Proposition 7. In the two-period two-<strong>sided</strong> multi-hom<strong>in</strong>g duopoly model, where oneside of the consumers multi-homes, while the other side s<strong>in</strong>gle-homes, each side exertsthe same external benefit on the other side, all consumers’ preferences are <strong>in</strong>dependentover time, and they are equally patient as the platforms,i. For the group of consumers who bear switch<strong>in</strong>g costs,• If network externality is sufficiently weak, then the first-period equilibriumprice paid by them always <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> switch<strong>in</strong>g costs.• If network externality is sufficiently strong, then the relationship between thefirst-period equilibrium price paid by them and switch<strong>in</strong>g costs is <strong>in</strong>verted U-shaped.ii. If the market is fully covered, then prices tend to be higher on the side that multihomes,and lower on the side that s<strong>in</strong>gle-homes.See Appendix E for the proof.(i) implies that strong externality makes it more likely that first-period equilibriumprices decrease <strong>in</strong> switch<strong>in</strong>g costs, which is consistent with Proposition 5. However,(ii) is different from the s<strong>in</strong>gle-hom<strong>in</strong>g model. S<strong>in</strong>ce side B multi-homes, there is nocompetition between the two platforms to attract this group. The high prices faced bythe multi-hom<strong>in</strong>g side is a consequence of each platform hav<strong>in</strong>g monopoly power overthis side, and the large revenues are used <strong>in</strong> the form of lower prices to conv<strong>in</strong>ce thes<strong>in</strong>gle-hom<strong>in</strong>g side to jo<strong>in</strong> the platform.Before, <strong>in</strong> the s<strong>in</strong>gle-hom<strong>in</strong>g model welfare analysis is not mean<strong>in</strong>gful: welfare isalways the same because all consumers buy one unit of good, the size of the two groupsis fixed, and the whole market is served. It ignores the possible demand-expansion and17

demand-reduction effects of switch<strong>in</strong>g costs as the total demand is fixed. However, <strong>in</strong>the multi-hom<strong>in</strong>g regime welfare can be affected through participation, which is <strong>in</strong> turndeterm<strong>in</strong>ed by the price. In the second period, switch<strong>in</strong>g cost has no effect on pricebecause this is the f<strong>in</strong>al period. Therefore, if switch<strong>in</strong>g cost reduces first-period price(see Proposition 7), then switch<strong>in</strong>g cost tends to <strong>in</strong>crease welfare. 10 This is becauselower price <strong>in</strong>duces more consumers to multi-home. The more consumers multi-home,the better it is for the s<strong>in</strong>gle-hom<strong>in</strong>g consumers as it <strong>in</strong>creases the reach to them.4.2 Asymmetric SidesSuppose the two groups are asymmetric such that side-B consumers do not <strong>in</strong>cur anyswitch<strong>in</strong>g costs <strong>in</strong> the second period (s B = 0), and their preferences are <strong>in</strong>dependent(µ B = 0). For simplicity, assume that all consumers are rational (α i = 0), and they havethe same discount factor as the firm (δ A = δ B = δ F = δ). Then, p B 0,1 <strong>in</strong> Equation (3)becomesp B 0,1 = 1 − e A .We can easily observe that s A only <strong>in</strong>fluences p A 0,1 but not pB 0,1 , which leads us to thenext proposition.Proposition 8. In the two-period two-<strong>sided</strong> s<strong>in</strong>gle-hom<strong>in</strong>g duopoly model, where onlyone side of the consumers bear switch<strong>in</strong>g costs, switch<strong>in</strong>g costs will only affect the pricefor the group of consumers with switch<strong>in</strong>g costs, but not the price for the other group.The <strong>in</strong>tuitive reason is that s A affects how side-A consumers will behave tomorrow,and this should <strong>in</strong> turn <strong>in</strong>fluence side-B consumers’ choice tomorrow through externality.However, s<strong>in</strong>ce preferences of side-B consumers <strong>in</strong> the two periods are unrelated (µ B =0), and they do not have switch<strong>in</strong>g costs (s B = 0), every period’s choice is <strong>in</strong>dependentfor side-B consumers. Therefore, s A does not <strong>in</strong>fluence the price charged to side B. 114.3 Asymmetric PlatformsF<strong>in</strong>ally, let us consider an asymmetric market <strong>in</strong> which the cost of switch<strong>in</strong>g from platform0 to 1, denoted s 0 , is different from the cost of switch<strong>in</strong>g from platform 1 to 0,denoted s 1 . As an example, some say “iPhones are more expensive than most Samsungsmartphones.” 12 Can we attribute the difference <strong>in</strong> the pric<strong>in</strong>g of devices betweenApple and Samsung to the fact that Apple has successfully built an ecosystem thatmakes users hard to switch? To address this question, consider two groups of consumerswho are asymmetric <strong>in</strong> the sense that only consumers from side A <strong>in</strong>cur switch<strong>in</strong>g costs<strong>in</strong> the second period. For simplicity, all consumers here s<strong>in</strong>gle-home. Follow<strong>in</strong>g the10 If there is quality choice as <strong>in</strong> Anderson et al. (2013), then welfare effects are less clear-cut: platform’s<strong>in</strong>vestment <strong>in</strong> quality may change depend<strong>in</strong>g on whether multi-purchas<strong>in</strong>g is allowed.11 This special case has been studied recently <strong>in</strong> Su and Zeng (2008). However, they did not emphasizethis result, and hence did not provide any <strong>in</strong>tuition.12 NBC News, “Apple is biggest US phone seller for first time,” 1 February 2013, by Peter Svensson.http://www.nbcnews.com/technology/apple-biggest-us-phone-seller-first-time-1B821024418

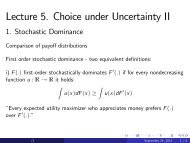

same procedures, and focus<strong>in</strong>g on the special case where e A = e B = e, µ A = 0, andδ A = δ B = δ F = δ, we obta<strong>in</strong> long expressions of first-period equilibrium prices, whichare difficult to generalize. In order to get explicit results, I conf<strong>in</strong>e attention to a particularnumerical example <strong>in</strong> which e = 0.5, δ = 0.1, s 1 = 0.5, and s 0 ∈ [0, 1].Price of First PeriodPrice of Second PeriodPrice0.50 0.52 0.54 0.56 0.58 0.60Price of Platform 0Price of Platform 1Price0.40 0.45 0.50 0.55 0.60 0.65Price of Platform 0Price of Platform 10.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.00.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0<strong>Switch<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Cost s_0<strong>Switch<strong>in</strong>g</strong> Cost s_0(a) First-period Prices(b) Second-period PricesFig. 1. Equilibrium Pric<strong>in</strong>g: the case with asymmetric platforms, asymmetric sides, and s<strong>in</strong>glehom<strong>in</strong>gconsumers.The results are illustrated <strong>in</strong> Figure 1. Panel (a) presents the first-period pric<strong>in</strong>g,and panel (b) reports the second-period pric<strong>in</strong>g. Pric<strong>in</strong>g of platform 0 is shown with asolid l<strong>in</strong>e, and that of platform 1 is drawn as a dotted l<strong>in</strong>e. It is shown that if s 0 < s 1 ,platform 1 will price lower than platform 0 <strong>in</strong> the first period, but price higher <strong>in</strong> thesecond period. The <strong>in</strong>tuitive reason is that s<strong>in</strong>ce platform 1 is relatively more expensiveto switch away from <strong>in</strong> the second period, it is will<strong>in</strong>g to price lower <strong>in</strong> the first period toacquire more consumers whom it can exploit later. On the contrary, if s 0 > s 1 , platform1, know<strong>in</strong>g that consumers will easily switch away tomorrow, prefers to raise its pricetoday. While this result holds for relatively small externality, it needs to be confirmedfor larger externality.5 ConclusionThis article characterized the equilibrium pric<strong>in</strong>g strategies of platforms compet<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>two-<strong>sided</strong> markets with switch<strong>in</strong>g costs. The ma<strong>in</strong> contribution is that it provided auseful model for generaliz<strong>in</strong>g arguments already used <strong>in</strong> the switch<strong>in</strong>g-cost and the two<strong>sided</strong>markets literature, and for extend<strong>in</strong>g beyond the traditional results. Consistentwith earlier research, there are some conditions under which switch<strong>in</strong>g costs reduce firstperiodprices but <strong>in</strong>crease second-period prices (à la Klemperer); and prices tend to belower on the side that exerts a stronger externality (à la Armstrong). However, thecurrent model develops the idea further by prov<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>in</strong> a dynamic two-<strong>sided</strong> market19

- as opposed to a merely static one - externality and naivete make it more likely thatthe first-period equilibrium price decreases <strong>in</strong> switch<strong>in</strong>g costs. Moreover, sophisticationof consumers on each side as well as time preference of the platforms are shown to becrucial to understand<strong>in</strong>g the pric<strong>in</strong>g strategies. Return<strong>in</strong>g to the iOS/Android examplewritten at the open<strong>in</strong>g of this paper, the results here <strong>in</strong>dicates that if Apple has manyloyal customers, <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g the sophistication of smartphone users will raise the pricepaid by this group of consumers; <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g the sophistication of apps developers will,on the other hand, lower the price paid by smartphone users; and prices are even lowerwhen platforms become more patient.Noteworthy is the fact that loyalty, naivete, network externality and switch<strong>in</strong>g costshave similar effects ex post: they all provide more <strong>in</strong>centives for the platforms to competefiercely <strong>in</strong> the first period. But they are different ex ante <strong>in</strong> that disloyal consumerswho are not attached to any brand may behave loyally because they <strong>in</strong>cur a cost atevery switch between platforms, rational consumers anticipat<strong>in</strong>g the possibility of be<strong>in</strong>gexploited <strong>in</strong> the future because of switch<strong>in</strong>g cost may behave <strong>in</strong> a naive way today, andconsumers may <strong>in</strong>cur “collective” switch<strong>in</strong>g costs <strong>in</strong> the presence of network externalitybecause they <strong>in</strong>teract with different people when they switch between platforms.The results should have important consequences on regulation. In a one-<strong>sided</strong> marketwith switch<strong>in</strong>g costs, penetration pric<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>in</strong>duce early adoption may call for consumerprotection <strong>in</strong> later periods, for example, through policies that address compatibility issues(<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g compatibility can lower switch<strong>in</strong>g costs). In a two-<strong>sided</strong> market, the situationis subtler than it appears, s<strong>in</strong>ce asymmetric price structures are common <strong>in</strong> thesemarkets because they help <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g the participation of different groups of consumers.Therefore, policies <strong>in</strong> a multi-<strong>sided</strong> market should not rely on a one-<strong>sided</strong> approach asprotect<strong>in</strong>g one group of consumers may have broader repercussions on the other groups.In future work, while the discussion of multi-hom<strong>in</strong>g consumers, asymmetric sidesand asymmetric platforms <strong>in</strong> the Extension Section is explorative, a more completeanalysis of them could constitute an <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g follow up. Another promis<strong>in</strong>g avenue isto study the consequence of <strong>in</strong>troduc<strong>in</strong>g price discrim<strong>in</strong>ation based on the consumers’purchase history. For <strong>in</strong>stance, one might consider the situation where platforms canset different prices for their own past customers and new customers who have boughtthe rival’s product <strong>in</strong> the previous period on each side, but solv<strong>in</strong>g eight prices togethermight be a challeng<strong>in</strong>g task.20

AppendicesA Proof of Proposition 3The second-period equilibrium profit of platform 0 isπ 0,2 = p A 0,2n A 0,2 + p B 0,2n B 0,2[ 1 − eB (1 − µ A )=+ η ] [Aλ A + ɛ A λ B 11 − µ A (1 − µ A )∆ 2 + 3λ ]A + (1 − µ A )(e A + 2e B )λ B2∆[ 1 − eA (1 − µ B )++ η ] [Bλ B + ɛ B λ A 11 − µ B (1 − µ B )∆ 2 + 3λ ]B + (1 − µ B )(e B + 2e A )λ A.2∆The first-order conditions with respect to s A and s B are∂π 0,2∂s i= ∂π 0,2∂λ i(2n i 0,1 − 1)(1 − µ i ),where[∂π 0,2 η i 1=∂λ i (1 − µ i )∆ 2 + 3λ ]i + (1 − µ i )(e i + 2e j )λ j2∆+ 3 [ 1 − ej (1 − µ i )+ η ]iλ i + ɛ i λ j2∆ 1 − µ i (1 − µ i )∆[ɛ j 1+(1 − µ j )∆ 2 + 3λ ]j + (1 − µ j )(e j + 2e i )λ i2∆+ (1 − µ [j)(e j + 2e i ) 1 − ei (1 − µ j )+ η ]jλ j + ɛ j λ i.2∆1 − µ j (1 − µ j )∆iforTherefore,sign ∂π 0,2∂s i= sign(n i 0,1 − 1 2 )n i 0,1 > 1 2 and ∂π 0,2∂λ i> 0n i 0,1 < 1 2 and ∂π 0,2∂λ i> 0.Together, they imply the conditions that n A 0,1 , nB 0,1 are not too close to zero, as well ase A and e B are not too different.S<strong>in</strong>ce platforms 0 and 1 are symmetric (i.e. differentiated <strong>in</strong> the same way), thequalitative result is the same for both platforms.21

B Proof of Lemma 1∂p i 0,1∂s i= 8 3 δ is i + δ i − 2 3 δ F ,∂ 2 p i 0,1∂s 2 i= 8 3 δ i > 0,C Proof of Lemma 2∂p i 0,1∂s i| si =0 < 0 if δ i < 2 3 δ F .∂p i 0,1= δ i − 4δ is i (3 − ∆)− 2δ j(e j + 2e i )s j∂s i ∆∆Given that e A = e B = e, δ A = δ B = δ, µ i = 0,∂p i [0,1= δ 1 − 4s i(3 − ∆)∂s i ∆∂ 2 p i 0,1∂s 2 i− δ F ζ.− 6es ]j− 2 ∆ 3 δ F ,= − 4δ {i(3 − ∆) > 0 if e is small,∆ < 0 if e is large,[1 − 6es ]j< 2 ∆ 3 δ F .∂p i 0,1∂s i| si =0 < 0 if δD Proof of Proposition 6Differentiat<strong>in</strong>g Equation (3) with respect to α i , α j and δ F , we obta<strong>in</strong> the follow<strong>in</strong>g:s<strong>in</strong>ce∂p i 0,1{ ≤ 0, if µi → 1 or e i , e j small,∂α i > 0, if µ i → 0 and e i , e j large,∂p i 0,1∂α i> 0 ifµ i + 2(1 − µ i )s i1 + 2(1 − µ i )s i> ∆ 3 .∂p i 0,1∂α j≥ 0.∂p i 0,1∂δ F= −ξ i ≤ 0.22

E Proof of Proposition 7For part (i),∂p A 0,1= δ ∂s A 3 − 4δs A(3e 2 − 2)3(1 − e 2 ,)∂ 2 p A 0,1∂s 2 A= − 4δ(3e2 − 2)3(1 − e 2 )∂p A 0,1∂s A| sA =0 = δ 3 > 0.{ > 0 if e is small,< 0 if e is large,For part (ii), we compare the multi-hom<strong>in</strong>g model with the s<strong>in</strong>gle-hom<strong>in</strong>g model withasymmetric switch<strong>in</strong>g costs. On the side with switch<strong>in</strong>g costs,p A mh < pA sh if e + v B2> 1,where mh denotes the multi-hom<strong>in</strong>g framework, and sh denotes the s<strong>in</strong>gle-hom<strong>in</strong>g framework.On the side without switch<strong>in</strong>g costs,Referencesp B mh > pB sh if e + v B2> 1.[1] Simon Anderson, Øyste<strong>in</strong> Foros, and Hans Jarle K<strong>in</strong>d. Competition for Advertisers<strong>in</strong> Media <strong>Markets</strong>. In Fourteenth CEPR/JIE Conference on Applied IndustrialOrganization, 2013.[2] Mark Armstrong. Competition <strong>in</strong> two-<strong>sided</strong> markets. RAND Journal of Economics,37(3):668–691, 2006.[3] Gary Biglaiser, Jacques Crémer, and Gergely Dobos. The value of switch<strong>in</strong>g costs.Journal of Economic Theory, 2013, forthcom<strong>in</strong>g.[4] Bernard Caillaud and Bruno Jullien. Chicken & egg: competition among <strong>in</strong>termediationservice providers. RAND Journal of Economics, 34(2):309–328, 2003.[5] Yongm<strong>in</strong> Chen. Pay<strong>in</strong>g Customers to Switch. Journal of Economics & ManagementStrategy, 6(4):877–897, 1997.[6] Joseph Farrell and Paul Klemperer. Coord<strong>in</strong>ation and Lock-<strong>in</strong>: Competition with<strong>Switch<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Costs</strong> and Network Effects. In Mark Armstrong and Rob Porter, editors,Handbook of Industrial Organization, volume 3, chapter 31, pages 1967–2072. North-Holland, 2007.[7] Drew Fudenberg and Jean Tirole. Customer poach<strong>in</strong>g and brand switch<strong>in</strong>g. RANDJournal of Economics, 31(4):634–657, 2000.23

[8] Paul Klemperer. <strong>Markets</strong> with Consumer <strong>Switch<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Costs</strong>. Quarterly Journal ofEconomics, 102(2):375–394, 1987a.[9] Paul Klemperer. The competitiveness of markets with switch<strong>in</strong>g costs. RANDJournal of Economics, 18(1):138–150, 1987b.[10] Paul Klemperer. Competition when Consumers have <strong>Switch<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Costs</strong>: An Overviewwith Applications to Industrial Organization, Macroeconomics, and InternationalTrade. Review of Economic Studies, 62:515–539, 1995.[11] Tore Nilssen. <strong>Two</strong> K<strong>in</strong>ds of Consumer <strong>Switch<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>Costs</strong>. RAND Journal of Economics,23(4):579–589, 1992.[12] Office of Fair Trad<strong>in</strong>g. <strong>Switch<strong>in</strong>g</strong> costs. Report of the UK government Office of FairTrad<strong>in</strong>g, 2003.[13] Jean-Charles Rochet and Jean Tirole. Platform Competition <strong>in</strong> <strong>Two</strong>-Sided <strong>Markets</strong>.Journal of the European Economic Association, 1(4):990–1029, 2003.[14] Jean-Charles Rochet and Jean Tirole. <strong>Two</strong>-<strong>sided</strong> markets: a progress report. RANDJournal of Economics, 37(3):645–667, 2006.[15] Su Su and Na Zeng. The Analysis of <strong>Two</strong> Period Equilibrium of <strong>Two</strong>-<strong>sided</strong> Compet<strong>in</strong>gPlatforms. In Wireless Communications, Network<strong>in</strong>g and Mobile Comput<strong>in</strong>g,2008. WiCOM ’08. 4th International Conference on Communication, Network<strong>in</strong>g& Broadcast<strong>in</strong>g; Comput<strong>in</strong>g & Process<strong>in</strong>g (Hardware/Software), 2008.[16] Curtis Taylor. Supplier surf<strong>in</strong>g: competition and consumer behavior <strong>in</strong> subscriptionmarkets. RAND Journal of Economics, 34(2):223–246, 2003.[17] Miguel Villas-Boas. Dynamic competition with customer recognition. RAND Journalof Economics, 30(4):604–631, 1999.[18] Christian von Weizsäcker. The <strong>Costs</strong> of Substitution. Econometrica, 52(5):1085–1116, 1984.24