Impacts of Urban Agriculture Annual Report.p65 - International ...

Impacts of Urban Agriculture Annual Report.p65 - International ...

Impacts of Urban Agriculture Annual Report.p65 - International ...

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

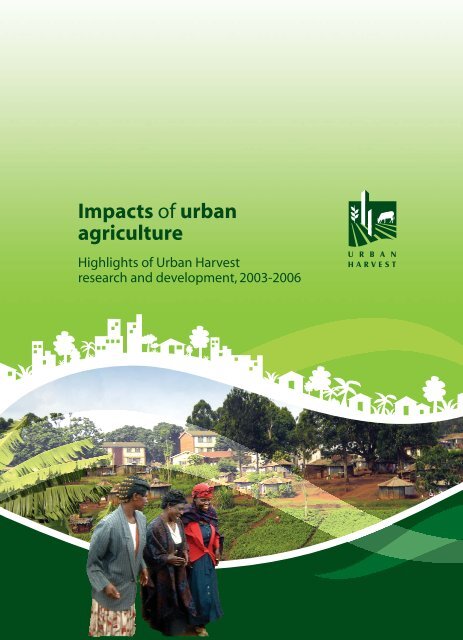

<strong>Impacts</strong> <strong>of</strong> urbanagricultureHighlights <strong>of</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> Harvestresearch and development, 2003-2006U R B A NHARVEST

1<strong>Impacts</strong> <strong>of</strong> urbanagricultureHighlights <strong>of</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> Harvestresearch and development, 2003-2006

2<strong>Impacts</strong> <strong>of</strong> urban agricultureHighlights <strong>of</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> Harvest research and development,2003-2006© <strong>International</strong> Potato Center (CIP), 2007ISBN: 978-92-9060-329-0The publications <strong>of</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> Harvest contribute importantinformation for the public domain. Parts <strong>of</strong> this publicationmay be cited or reproduced for non-commercial use providedauthors rights <strong>of</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> Harvest are respected andacknowledged, and you send us a copy <strong>of</strong> the publicationciting or reproducing our material.Published by the <strong>International</strong> Potato Center (CIP), convenerfor <strong>Urban</strong> Harvest. CIP contributes to the CGIAR missionthrough scientific research and related activities on potato,sweetpotato, and other root and tuber crops, and on themanagement <strong>of</strong> natural resources in the Andes and the othermountain areas. www.cipotato.orgProduced by Communications and Public AwarenessDepartmentWritting and editing: Cathy Barker, Gordon Prain, MaartenWarnaars, Ximena Warnaars, Lisa Wing, Freda WolfProduction coordinator: Cecilia LafosseDesign and layout: Elena Taipe, Nini Fernández-ConchaPrinted in Peru by: Comercial Gráfica SucreCopies printed: 500November 2007

Table <strong>of</strong> contents3Introduction 5Introduction to urban livelihoods and markets 9Flower power in the Philippines: Strengthening the contribution <strong>of</strong> thejasmine industry to urban livelihoods 10Meals on wheels add a new dynamic to pig raising in Hanoi 13Identifying best bet marketing opportunities for Kampala farmers 17What should I feed my child? Perceptions <strong>of</strong> foods for young children 19among Lima mothersIntroduction to <strong>Urban</strong> Ecosystem Health 21Adopting Farmer Field Schools to urban realities in Lima, Peru 22Research for a cleaner future: Heavy metal contamination in Kampala 24Dirty secret treasures in Nairobi 27Improving the quality <strong>of</strong> irrigation water in Lima 30Introduction to Stakeholder and Policy Dialogue 33Getting agriculture on the municipal agenda in Lima 34An urban agricultural model in the making: Kampala, Uganda 37Improving the integration <strong>of</strong> urban agriculture in national and local 40government in Kenya, through multi-stakeholder platformsNetworking 43Local and global networkingNetworking and capacity building activities 2003-2006 45Publications 52Networking partners 56Investments partners 59<strong>Urban</strong> Harvest researchers, students and interns 2003-2006 60Abbreviations and acronyms 63

IntroductionThe CGIAR 1 System-wide Initiative on <strong>Urban</strong> and Periurban<strong>Agriculture</strong>, now known as <strong>Urban</strong> Harvest, wasformally launched in late 1999, to focus the efforts andrelevant collective knowledge <strong>of</strong> the Alliance Centerstowards collaborative development <strong>of</strong> innovations inurban and peri-urban agriculture. Since its inception,<strong>Urban</strong> Harvest has been hosted by the <strong>International</strong>Potato Center (CIP) and the global coordination <strong>of</strong>fice<strong>of</strong> the Initiative was established in CIP’s Limaheadquarters in early 2000. Between 2001 and 2002,regional coordination capacity was established on theILRI Campus in Nairobi for Sub-Saharan Africa and inCIAT’s facilities in Hanoi, Vietnam.The broad goals <strong>of</strong> <strong>Urban</strong> Harvest which have guidedthe Initiative from its beginnings are to enhance,through local agriculture, the food, nutrition and incomesecurity <strong>of</strong> the urban and peri-urban poor, reducenegative urban environmental and health effectsamong urban populations and stimulate the integration<strong>of</strong> agriculture within urban management strategies.These interdependent goals have been operationalizedthrough a research framework which draws on thesustainable livelihoods framework and eco-systemshealth thinking. The framework distinguishes threeresearch and development themes relating to urbanlivelihoods and markets; urban ecosystems health;and stakeholder and policy dialogue (see Box). Theframework underlines the different role andcharacteristics <strong>of</strong> agriculture as one moves from rural,through peri-urban to intra-urban conditions. Thearticles in this report, which highlight some <strong>of</strong> theprogram achievements between 2003 and 2006, alsocapture the particularities <strong>of</strong> the urban context. Foodand nutrition insecurity are highly correlated withconditions in many rural areas <strong>of</strong> the developing world.Yet the high cost <strong>of</strong> food in cities, the restricted accessto own food production, unhealthy living conditionssuffered by low-income urban families combined withpoor diets – including increasing consumption <strong>of</strong>refined foods – all create urban hot-spots <strong>of</strong> food andnutrition insecurity. The article on mothers’ perceptions<strong>of</strong> animal source food for your children in Lima, wherearound 50% suffer anemia, is part <strong>of</strong> a broader effort tostimulate increased consumption <strong>of</strong> these iron-richfoods. Stimulating increased access to urban foodproduction is supporting what local people alreadyknow: it is a path towards better nutrition and health.Although many migrants move to cities in theexpectation <strong>of</strong> more and better-paid jobs than in the51 The Consultative Group on <strong>International</strong> Agricultural Research is a strategic alliance <strong>of</strong> members, partners and international agricultural centers that mobilizes science tobenefit the poor. It aims to achieve sustainable food security and reduce poverty in developing countries through scientific research and research-related activities in thefields <strong>of</strong> agriculture, forestry, fisheries, policy, and environment

6country-side, we know that many cities have as much as90% informal employment, meaning occasional andprecarious opportunities for earning income. <strong>Urban</strong> cropproduction and livestock-keeping have been shown to becomplementary activities to casual non-farm work formany families and improving their income-generatingpotential can help them move out <strong>of</strong> poverty. Articles fromthe Philippines, Vietnam and Uganda show the specialopportunities that urban and peri-urban producers haveto access local input and produce markets.<strong>Urban</strong> ecosystems have both health risks and economicand environmental benefits for producers and consumers.<strong>Agriculture</strong> is a key part <strong>of</strong> the eco-system, generatingrisks through use <strong>of</strong> toxic inputs in densely populatedareas and vulnerable at the same time to becoming apathway for biological and chemical contaminants in theecosystem, directly via soil or water to producers andindirectly facilitating the passage <strong>of</strong> contaminants intourban food systems. The articles on biologicalcontamination <strong>of</strong> irrigation water in Lima and heavy metalcontamination in Kampala identify some <strong>of</strong> theseproblems and describe potential solutions. The organicwastes in the urban ecosystem carry nutrients which canbe used at low or no cost by urban producers. The articleon producer schools in Lima describes the way themethod has helped producers transform theiragriculture towards more ecologically friendlyproduction, using local organic wastes. The Nairobiarticle talks about the complicated flows <strong>of</strong> wastesentering and leaving and circulating within Nairobi,and the opportunities these provide for income.Compared to rural settings, cities are more heavilyregulated and experience more intensive competitionamong a wider range <strong>of</strong> stakeholders for resources.<strong>Urban</strong> agriculture has in the past been at best ignoredand at worst restricted or prohibited by localgovernments in the developing world. As many citiessuch as Havana, Rosario, Vancouver, Cairo and Yunnanhave already shown, agriculture can become anintegral part <strong>of</strong> good environmental management <strong>of</strong>urban space. Cities and their inhabitants need greenspace to survive and an <strong>Urban</strong> Harvest supportedstudy <strong>of</strong> urban heat islands in Manila has clearly shownthe cooling effect <strong>of</strong> green spaces in the city. The threearticles in the section on Stakeholder and policydialogue present examples <strong>of</strong> how it is possible – noteasy, but possible – to influence policy processes andorganizational change to better integrate agriculturein urban planning and development and by so doing,making cities more sustainable places.

7RESEARCH FRAMEWORKThe <strong>Urban</strong> Harvest research framework (see diagram)draws on earlier insights into sustainable livelihoods andurban eco-system health. In complex city ecosystems,which include informal economies and social networks,poor households depend on multiple income sources anda wide range <strong>of</strong> non-material assets to ensure theirlivelihood. Inadequate assets can leave householdsvulnerable to economic, environmental, health, andpolitical stresses and shocks (the vulnerability context).Five types <strong>of</strong> capital assets are distinguished. Naturalcapital includes the quantity and quality <strong>of</strong> accessibleland and water as well as biodiversity. “Hidden” naturalresources, such as vacant lots, unused water surfaces andnutrient-rich solid and liquid wastes are common inurban areas, but are <strong>of</strong>ten unrecognized by localgovernments. Physical capital refers to such assets asbuildings, equipment, seeds, animals and own transport.Human capital includes family labor, knowledge andhealth status. Available income and savings comprisefinancial capital. Social capital includes the access tonetworks, groups, trust and support.The deployment <strong>of</strong> assets in household strategies, theinfluences and impediments experienced throughengagement with the institutional and policy fabric <strong>of</strong>the city (structures and processes), the outcomesachieved, are part <strong>of</strong> livelihood processes, which in turnexert positive and/or negative ecosystem feedback onthe livelihood assets and on the vulnerability context.<strong>Urban</strong> Harvest identifies three research themes:Stakeholder and policy analysis and dialogue seeksunderstanding <strong>of</strong> the actors, policies and institutionsconcerned in urban agricultural activities and developsmethods for communication and consensus amongactors and legitimacy for urban agriculture in policy andregulatory schemes. Livelihoods and markets targetsproduction, processing, marketing and consumptionsystems along the rural-urban transect and identifiestechnology interventions to enhance income and foodand nutrition security. <strong>Urban</strong> ecosystem health focusesattention on the feedback mechanisms betweenpeople’s actions and population, community andenvironmental health.

Introduction to urban livelihoods and marketsThe sustainable urban livelihoods frameworkrecognizes that increasingly in rural settings, and verymuch so in complex urban contexts, poor householdsdepend on a diversity <strong>of</strong> strategies to ensure foodsecurity, income and well-being. These diversestrategies depend on a set <strong>of</strong> household assets orcapitals: natural capital (such as land, water, pollutants);financial capital (money); physical capital (houses,equipment, vehicles, animals, seeds); human capital(labor power, ie. health, and capacity or skill); and socialcapital (networks <strong>of</strong> trust, exchange and mutualsupport, which all individuals and households maintainto a greater or lesser degree).Deployment <strong>of</strong> assets in household livelihoodsstrategies also depends on the influences andimpediments that household members experiencewhen they deal with urban institutions, such asmunicipal regulation, or policies <strong>of</strong> local marketingpractices. This constrained deployment <strong>of</strong> assets and thelivelihood outcomes which they achieve are all part <strong>of</strong>the urban livelihood process. Inability to adequatelydeploy assets can leave households vulnerable toeconomic, environmental, health, and political stressesand shocks, which are referred to as the “vulnerabilitycontext”: the level <strong>of</strong> susceptibility to poverty and thedifficulty <strong>of</strong> moving out <strong>of</strong> poverty. Conversely, betteraccess to social and material assets, improvedcapabilities and diversified activities to deploy theseassets, combined with a more supportive institutionalcontext, can move households out <strong>of</strong> poverty.The participation <strong>of</strong> men and women in agriculturevaries along the rural-to-urban transect, as do otheraspects <strong>of</strong> farming systems, such as land area, tenancy,principal crops and animals production, food securityand marketing strategies and health risks. Women playa dominant role in many types <strong>of</strong> urban agriculturesystems, especially those involving small livestock andmultiple food crops. The important role women play in“feeding cities” indicates the importance <strong>of</strong> workingwith them in action research interventions. Women’sfrequent access to sources <strong>of</strong> social capital (women’sassociations) provides scaling out opportunities.9

Flower power in the Philippines:Strengthening the contribution <strong>of</strong>the jasmine industry to urban livelihoods10Sampaguita, the jasmine buds adopted by thePhilippines’ as its national flower, is primarily used for theproduction <strong>of</strong> garlands, which in turn are used asceremonial and decorative ornaments. As many as120,000 low-income households in the Manila region—from sampaguita farmers to garland makers, to childrenselling garlands in Manila—depend on these garlands asan important source <strong>of</strong> income. An in-depth assessmentstudy conducted by <strong>Urban</strong> Harvest partner institutionssought to improve the contribution <strong>of</strong> the sampaguita(jasmine) enterprise system to the economic and socialwell being <strong>of</strong> key players in the Manila metropolitanregion by identifying the benefits and constraints <strong>of</strong> thisthriving industry.The University <strong>of</strong> the Philippines Los Baños and CIP-UPWARD carried out studies in the municipalities <strong>of</strong> SanPedro and Calamba, Laguna, and Manila in the Philippines(between 2001 and 2004) that highlighted theimportance <strong>of</strong> the sampaguita livelihood system tohouseholds and to the community <strong>of</strong> San Pedro and tothose involved in marketing in Metro Manila.The entire system involves eight key players: thefarmer (who produces sampaguita flowers and otherraw materials, mostly men); the flower picker (whoharvests daily the floral buds, mostly women andchildren); the supplier (who collects flowers fromfarmers and transports them to San Pedro, <strong>of</strong>tentimes farmers’ wives); the abaca fiber cleaner (whocleans abaca fibers, mostly old women and men); thevendor (who buys wholesale the raw materials fromfarmers and suppliers and retails them to contactorsand garland-makers); the garland-making contractor(who buys raw materials from vendors and contractsgarland-makers, mostly women); the garland maker(who strings together the flowers, mostly women andchildren); and the garland seller (who peddles thesampaguita garlands in Manila, mostly women andchildren).The study identified the most pressing constraints <strong>of</strong>the sampaguita economic system and <strong>of</strong>feredsolutions to such limitations. Aside from asserting thatthis is a viable peri-urban industry, the study—whichinvolved various surveys, secondary data, field visits,focus group discussions and interviews with keyinformants—stressed the importance <strong>of</strong> involvinglocal and international organizations, policy makers,and government agencies in supporting this trade asan important contribution to livelihoods in themetropolitan region.The sampaguita livelihood system in San Pedro,Laguna, a suburban town 29 kilometers south <strong>of</strong>Manila, is anchored primarily on the production <strong>of</strong>flowers and their preparation into garlands. The townserves as the point <strong>of</strong> convergence linking farmingactivity in rural areas to the marketing <strong>of</strong> garlands inurban centers. Flowers produced in rural farms arebought, traded and transformed into garlands in themunicipality, with the garlands being subsequently

sold in adjacent Metro Manila. Data shows that up to2.8 million flower buds are traded daily in San Pedro.11As the study points out, the various livelihood activitiesrevolving around garland making in San Pedro providenumerous benefits to everyone involved. At theforefront <strong>of</strong> these benefits are employment and incomegeneration, socio-cultural benefits (making the youthproductive and empowering woman), and thepromotion <strong>of</strong> loyalty, trust and a sense <strong>of</strong> traditionamong those involved in the garland production chain.However, as with any other agribusiness venture, thesampaguita enterprise is beset with problems.Among the most pressing is the susceptibility <strong>of</strong>sampaguita to insect attack, which in turn leads t<strong>of</strong>armers’ extensive use <strong>of</strong> pesticides. This not only harmsthe environment and raises production costs, but alsoaffects the health <strong>of</strong> those who handle the flowers. Allplayers along the chain, from growers to pickers togarland stringers, have complained <strong>of</strong> skin allergies andbreathing difficulties and suspect it is due to pesticideresidue in the flowers. Woman and children are the mostexposed to health risks because they are in charge <strong>of</strong>picking the flower’s buds and therefore re-enter thefarm less than 12 hours after spraying.With this in mind, health risks resulting from pestmanagement and pesticide use were a major focus <strong>of</strong>the study. Farmers are <strong>of</strong>ten oblivious to the negativehealth effects that can result from using either very toxicor unsafe pesticides, or simply using too much <strong>of</strong> it.Some sampaguita growers spray as much as four timesa week to combat the whitefly and budborer and otherinsect pests and diseases.The study also identified other major problems andconstraints faced by key players in the garland productionchain, including competition with other sellers andsuppliers, a lack <strong>of</strong> capital to increase business, nonpayment<strong>of</strong> loans by customers, irregular price fluctuations<strong>of</strong> flowers and a lack <strong>of</strong> better methods <strong>of</strong> storing flowers.Rapid urbanization in the municipality is also a threat.At the forefront <strong>of</strong> CIP-UPWARD’s efforts to help findsolutions to the main constraints affecting thesampaguita livelihood in the Philippines is thedevelopment <strong>of</strong> an Integrated Pest Managementscheme to reduce the frequency <strong>of</strong> pesticideapplications and encourage the selection <strong>of</strong> less-toxicones. Non-pesticide based management was alsointroduced including the use <strong>of</strong> biological pest controls,better farm management practices that minimize pestinfestations, and replacement <strong>of</strong> sick and oldsampaguita plants.

12At the policy level, CIP-UPWARD-<strong>Urban</strong> Harvest helpedorganize a multi-disciplinary and inter-institutional forumthat discussed the problem <strong>of</strong> excessive pesticide use andlack <strong>of</strong> registered crop protection products forsampaguita. The Fertilizer and Pesticide Authority <strong>of</strong> thePhilippines, representatives <strong>of</strong> crop protectioncompanies, government research institutions andsampaguita farmers attended this forum. An Ad-hoccommittee was formed in this meeting to discuss andstudy policy recommendations on pesticide use forsampaguita.At post-production level, this study emphasized theimportance <strong>of</strong> identifying better storage methods forsampaguita floral buds, which can only be preserved for48 hours using the existing technology <strong>of</strong> packing themin Styr<strong>of</strong>oam containers with ice. This forces garlandmakersand contractors to only buy what they can processin one day. The study points out that better storagemethods could allow them to manage their timemore efficiently.Another major concern identified in the study wasthe reduction in the yield and the perishability <strong>of</strong>sampaguita flowers. More information on the floralbiology (i.e. flowering and pollination) <strong>of</strong> thesampaguita could be used, among other things, tobreed new varieties that could have flowers <strong>of</strong> variedcolors and that are more resistant to pests anddiseases. Determining the nutrient requirements <strong>of</strong>sampaguita and even using organic manure as anutrient source to enhance yield and quality was alsosuggested in the study.Other opportunities discussed included thecommercial feasibility <strong>of</strong> extracting essential oils fromthe sampaguita flower.

Meals on wheels add a newdynamic to pig raising in Hanoidemand for meat, especially in urban centers. In Cat Quecommune on the outskirts <strong>of</strong> Hanoi, already heavilydependent on livestock raising due to limitedagricultural land, households started to specialize indifferent stages <strong>of</strong> pig raising: piglet (called giong: “seedpig”) supply and raising medium-sized pigs (got) to besold for fattening for final marketing as meat. Cat Quefarmers began to specialize in intensive production <strong>of</strong>the intermediate got stage <strong>of</strong> pig raising: purchasingweaned piglets from sow/piglet raisers at 5 or 6 kg toraise them to between 25 and 30 kg, to sell to meat pigraisers who then fatten them up to between 80 to 110kg. Raising “growing pigs” (as got would be called in UShog raising terminology) was soon adopted by almostall <strong>of</strong> the 2,600 households in Cat Que. The system thatwas developed helped create an effective link betweenrural and peri-urban and urban households in “ruralurbanenterprise clusters”.13Vietnamese urban and peri-urban householdscommonly raise a few pigs for market in their backyards.This activity adds to their income, puts a little pork ontheir own table, especially for the Lunar New Year, andthe manure can be used or sold as fertilizer. However,the villages <strong>of</strong> Cat Que commune near Hanoi haveturned pig raising into the hub <strong>of</strong> a complex local cluster<strong>of</strong> agro-enterprises. The pig raising industry in Vietnamis very dynamic, like many things in Vietnam - itundergoes rapid changes in response to theintroduction <strong>of</strong> new materials and knowledge.Following the economic reforms <strong>of</strong> Doi Moi in the mid‘80s, the government allowed the emergence <strong>of</strong> privatemarkets. The resulting rising incomes increased theCat Que enterprise clusters consist <strong>of</strong> piglet (giong)producers and traders, got-raisers, feed and medicinesuppliers, veterinarians, got-collectors, pig fatteners andmanure collectors. All the got-raisers agree that thebiggest advantage <strong>of</strong> clustering together is the marketthey collectively create. It is common for a householdto raise 500 to1000 got, up to 5000 a year. Each cycletakes 45 to 60 days depending on the quality <strong>of</strong> the babypiglets and their growth potential, diet, health andmanagement.An <strong>Urban</strong> Harvest team including The <strong>International</strong>Potato Center (CIP), The <strong>International</strong> Center for Tropical<strong>Agriculture</strong> (CIAT) and national researchers from HanoiAgricultural University and the National Institute forAnimal Husbandry, have been analyzing the complexset <strong>of</strong> interrelated pig-raising issues to provide a basisfor elaborating an enterprise plan. The intention wouldbe to improve the system, identifying the actors andconcerns <strong>of</strong> the different aspects <strong>of</strong> the pig productionchain, participating in joint identification and discussion

tours <strong>of</strong>fered all over the country. In 2002, it wasestimated that there were more than 1.3 millionmotorbikes in Hanoi (1 motorbike per 2 people onaverage) and by 2004 the estimate was up to 2 millionmotorbikes. They are used for family transportation,taxis and for cargo. For the trip to the Cat Que villages,the highly liquid institutional and restaurant foodresidues are carried in sealable blue plastic barrels,which hold about 70 kilos each. A motorbike can beloaded with three <strong>of</strong> these barrels: one on each side <strong>of</strong>the rear wheel, a third behind the driver and sometimesa small container is even placed between the legs <strong>of</strong>the driver on the bike frame. The larger the volume, themore the reduction in transport costs. Nevertheless,transportation logistics are complex, because even aslight, sudden swerve <strong>of</strong> the motorbike can set <strong>of</strong>f thesloshing dynamics within the barrels that can cause thebike, rider and cargo to slew <strong>of</strong>f the road.The pigs in Cat Que villages grow fat on these gourmetwastes, which are used as the major feed source. For each<strong>of</strong> the two feedings a day they are boiled up in largecauldrons, added on top <strong>of</strong> local agricultural productsto prevent sticking, for about 1.5 hours, over fires fueledby coal slurry. Rice bran is added a few minutes towardthe end <strong>of</strong> the boiling time. One or two trips to the cityper day are required, depending on the number <strong>of</strong> pigs.Though animal nutritionists say three feedings wouldbe better, the constraints <strong>of</strong> time simply rule out thispossibility. Sometimes the women’s first trip into thecity is at 1:00 or 2:00 a.m. to sell vegetables, returning at5:00am, when the husbands leave to fetch the foodresidues for the pigs. Between two and five hours <strong>of</strong>labor time a day is required for transport. This tends tobe men’s work because <strong>of</strong> the heavy, unstable load.Although no nutritional analysis <strong>of</strong> the food wastes hasbeen concluded yet, the residues from restaurants andfood preparing institutions are thought to be highlynutritious, although they have to be picked over because<strong>of</strong> small inorganic objects that get mixed in, such assmall plastic bottles. T<strong>of</strong>u residues can also be purchasedfrom many small-scale t<strong>of</strong>u enterprises in Hanoi, but aremore expensive and farmers generally agree restaurantwaste is higher in nutrients and better for fattening pigs,even though the supply <strong>of</strong> t<strong>of</strong>u residues is more secure.Commercial supplements are used sparingly to staywithin the narrow pr<strong>of</strong>it margin.Even though the residents <strong>of</strong> Cat Que have significanteconomic advantage over traditional farming orlivestock raising, they would like to explore thepossibilities <strong>of</strong> further improving the pr<strong>of</strong>itability andresolving the problem <strong>of</strong> waste and environment.Ironically, while recycling restaurant residues from Hanoipartially alleviates one environmental hazard, theincreased volume <strong>of</strong> resident pigs causes another in CatQue. Measures to manage or eliminate the waste needto be identified. One possibility is to construct canalsso the waste can be directed away from the communeinto a holding tank for disposal. Pig manure is anexcellent fertilizer. If the manure can be processed intoa higher quality and value fertilizer, the market will alsoopen up. It is, therefore, possible to experiment withsmall scale manure processing, but it would be betterto adopt larger scale processing.There are enough raw materials for fertilizer processingon a large scale. This would, however, require majorinvestment that must be provided either by thegovernment or private investors. To attract such aninvestment from either party, analysis must beperformed to demonstrate the extent <strong>of</strong> the economicand environmental benefits.15

16Figure 1: Got-raising based enterprise clustered in Cat Que

Identifying best bet marketingopportunities for Kampala farmersDirect, low-cost linkage to diverse urban markets isboth an opportunity and a challenge for urban and periurbanproducers. Through its research theme <strong>of</strong>livelihoods and markets, <strong>Urban</strong> Harvest developsstrategies to help producers better access theopportunities and confront the challenges.17<strong>Urban</strong> agriculture plays a key role within and aroundthe rapidly growing city <strong>of</strong> Kampala, where agricultureactivities contribute up to 40% <strong>of</strong> the total foodconsumed there. More than half <strong>of</strong> the land both withinKampala’s municipal boundaries and peri-urban areasis used for agricultural purposes, with an estimated 30%<strong>of</strong> the households engaged in urban agriculture.Successful marketing <strong>of</strong> products thus has majorlivelihood implications for large numbers <strong>of</strong> urbanfarmers.Beginning in 2002, an <strong>Urban</strong> Harvest team, led by the<strong>International</strong> Center for Tropical <strong>Agriculture</strong>,Colombia (CIAT)and the <strong>International</strong> Center forTropical <strong>Agriculture</strong>, Nigeria (IITA) assessed themarket opportunities for urban and peri-urbanfarmers in Kampala and helped them identify aportfolio <strong>of</strong> agricultural products with marketdemand whose production is technically andeconomically feasible.Market surveys compared levels <strong>of</strong> demand for theproducts currently being produced by farmers there andidentified a number <strong>of</strong> new fruits and vegetables withhigh potential.The overall study involved: a rapid urban appraisal tocharacterize communities and identify agriculturalcommodities being produced by urban farmers forincome generation; a study to capture opportunitiesfor existing and potential products, and an evaluation<strong>of</strong> the most promising options for urban and periurbanfarmers.Of the 38 products identified and evaluated, 8 wereselected as high potential and their production andeconomic characteristics were further assessed. Theevaluation criteria considered to select the short list <strong>of</strong>8 products were: market demand (those in high demandand scarce supply), production feasibility in an urbansetting, present production by urban and peri-urbanfarmers and government policies.Meanwhile, the methodology used for the selectionprocess was the rapid market assessment. Thisinformation-gathering method, which involves a series<strong>of</strong> carefully structured and documented in-depthinterviews, provided a quick and effective way todiscover and understand market needs andopportunities.The rapid market assessment identified the followingmarket opportunities: poultry products (broilers, eggsand local/indigenous chicken), vegetables (leafyvegetables, tomato, carrot, onion, cocoyam, mushroom,cauliflower and red pepper), fruits (avocado, mango,

18pawpaw, pineapple, watermelon, jackfruit, tangerine,apple, pear, orange), meat (beef and pork) and fresh milk.Information on purchasing requirements—quality,packaging, minimum volumes, frequency <strong>of</strong> delivery,etc—was obtained for all these products.The selected products were presented to farmers, whochose the most appropriate enterprises within theirmeans. These were: mushrooms, poultry and pork. Thesewere identified as high value products whose productionis less risky than other alternatives that may provide ahigher income, such as fruits and vegetables.Market studies indicated, however, that the identifiedproducts had the potential to increase farmers’ incomeonly if they met the demands <strong>of</strong> traders in terms <strong>of</strong> quality,quantity, continuity and price. To fulfill these requirements,project participants concluded that they must eitherconfine themselves to the local or niche markets that theycan supply with their present production levels, or movetoward collective action as a means <strong>of</strong> supplying greatervolumes to those markets indicating growth possibilities.Moreover, providing support services to farmers toovercome these initial “barriers to entry” (i.e. access toseeds, technical assistance, contacts with potentialbuyers, etc.) is key in helping farmers develop their cropproduction into a sustainable income-generating activity.At present, services either do not exist or are orientedmore toward production with little attention paid tomarketing or enterprise organization.The inter-institutional and multidisciplinary nature <strong>of</strong>this particular project is an attempt to bring togetherappropriate actors from both research anddevelopment to establish such services and work withthe local community to develop more efficiententerprises.The findings from this work are now beingincorporated into a recently installed research anddevelopment project in Kampala, part <strong>of</strong> the<strong>International</strong> Development Research Centre (IDRC)-supported Focus City program. 11 The Focus City Research Initiative (FCRI) selected eight cities around the world where multistakeholder City Teams are working in partnership over four years to researchand test innovative solutions to alleviate poverty.

What should I feed my child?Perceptions <strong>of</strong> foods for young childrenamong Lima mothersWhat types <strong>of</strong> food do people give their children?Are choices made on the basis <strong>of</strong> custom, economy,education – or a combination <strong>of</strong> these? A study wasconducted in a handful <strong>of</strong> communities on the outskirts<strong>of</strong> Lima to determine caregivers’ perceptions and habitsregarding child nutrition, specifically their use <strong>of</strong> animalbasedproducts in the diet <strong>of</strong> young children betweensix and twenty four months old.19The study, carried out jointly in 2003 by <strong>Urban</strong> Harvestand Peru’s Nutritional Research Institute (IIN), is set tohelp develop future programs and educational materialaimed at combating infant malnutrition with anemphasis on incorporating animal-based products suchas meats, milk and eggs into babies’ meals.A vital source <strong>of</strong> protein, vitamins, iron, zinc and calcium,animal-source foods are important for human growthand development, particularly during children’s firstyears <strong>of</strong> life, when mental and physical development ismost rapid and when the incorporation <strong>of</strong> foodscomplementary to breast milk is <strong>of</strong> utmost importance.Access to meat and other animal-based products,however, is limited in rural and peri-urban areas such asthe four shantytowns where the study was carried out,as these products are more difficult and more expensiveto obtain than say, vegetable crops or processed goods.In Peru, <strong>of</strong> the half million children under the age <strong>of</strong> five,one in four suffers from chronic malnutrition and onein every two has anemia—a disorder caused by a dietaryiron or vitamin deficiency.Through this and other projects, the <strong>International</strong> PotatoCenter (CIP) and partner institutions are committed toimproving children’s nutrition and overall health byencouraging mothers to adopt good feeding habits,disseminating information on the health benefits <strong>of</strong>consuming animal-based products, and providingrecommendations on the incorporation <strong>of</strong> suchproducts into daily meals.The methodology used in this particular study includedin-depth one-on-one and group interviews withcaregivers—including home animal breeders—as wellas written surveys and questionnaires. During the initialinformation gathering process, project leaders appliedthe Pile Sort technique, which involves users groupingcards into piles according to specific topics. This simpleand effective information sorting method helpedstructure the content <strong>of</strong> the study.Study results brought to light, among other things,reasons why caregivers prefer one animal-basedproduct over another: the availability <strong>of</strong> such productsand the perception (and current use) <strong>of</strong> these products.Caregivers in these communities generally prefer t<strong>of</strong>eed their children chicken liver, chicken meat, milk andegg as their main source <strong>of</strong> animal-based goods. Fish,chicken meat, and yogurt are the products that they

20(and their children) least favor and/or least consume. Thestudy discovered that these preferences are closely tiedto the caregiver’s economic situation, access to thesegoods and cultural eating habits.<strong>Urban</strong> Harvest aims to incorporate and promote animalbasedproducts that are produced locally and/or are easilyobtained into aid programs by providing caregivers withideas on different meal preparations and presentations,while emphasizing the nutritional importance <strong>of</strong> suchproducts.Indeed, one <strong>of</strong> the main causes <strong>of</strong> infant malnutrition iscaregivers’ inadequate feeding practices which include,among other things, over-diluting infant’s food, notfeeding them enough food throughout the day, and notincorporate animal foods (meat, poultry, fish and eggs)into meals – or even totally excluding them.This study considers the fact that not all children are thesame: feeding practices differ from child to childdepending on their growth, development and age.What does remain a constant, however, is the fact thatmalnutrition affects an infant’s health, growth anddevelopment, and therefore can lead to a lower quality<strong>of</strong> life as an adult.

Introduction to <strong>Urban</strong> ecosystems healthUnderstanding both positive and negative healtheffects on households and the urban ecosystem isessential for determining strategies that multiplybenefits and mitigate risks. The urban ecosystemshealth framework provides a better lens for analyzinghealth issues related to urban agriculture. It is based onthe interdependence <strong>of</strong> human health with the health<strong>of</strong> the natural, physical and social environments withinwhich urban populations live. It focuses attention on sixdimensions <strong>of</strong> urban health where urban and peri-urbanagriculture (UPA) can have both a positive and negativeimpact. These dimensions include: health <strong>of</strong> urbanpopulations, communal health, quality <strong>of</strong> the builtenvironment, quality <strong>of</strong> the physical environment,health and resilience <strong>of</strong> the biotic community and thehealth <strong>of</strong> the natural ecosystems.Many urban producer households are vulnerable tocontaminants such as pesticide use, liquid and solidwastes. Heavy dependency and use <strong>of</strong> pesticides indensely populated urban areas create health problemsfor producers and the natural fertility <strong>of</strong> soils. AlternativeIntegrated Pest Management strategies are beingintroduced, through farmer field schools, to mitigatethese negative effects. Moreover, water contamination,derived from inadequate water treatment plants indeveloping countries, causes many health problems forurban dwellers. The use <strong>of</strong> either wastewater orcontaminated river water as a source <strong>of</strong> irrigation causesmany health issues for producers as well as consumers.Access to natural and physical resources for agricultureand the potential impact <strong>of</strong> these resources onagriculture is important, although this is not enough.Natural and physical resources, <strong>of</strong> potentially great useto urban agriculture, go unrecognized by local <strong>of</strong>ficialsor remain underutilized by poor urban households.Hence the concept <strong>of</strong> urban resources recognitionand use is employed to address the high potential <strong>of</strong>urban agriculture to mobilize and add value to naturaland physical resources, such as water, and, thus,strengthen and balance capital assets available to urbancommunities. Strongly linked to both the livelihoodsand urban ecosystems health frameworks, this will formthe basis <strong>of</strong> a third module with an emphasis onresource mapping, modeling and policy development.21

Adopting Farmer Field Schoolsto urban realities in Lima, Peru22products. Most producers in the area have limitedknow-how or money to improve the quality andefficiency <strong>of</strong> production and therefore have no optionbut to sell their products to local markets at a nominalprice.Implemented in 2004 and 2005, this <strong>Urban</strong> Harvestproject utilized the Farmer Field Schools (FFS)approach, which involves intensive adult educationand social learning techniques to stimulateagricultural education. This approach, which up untilnow had only been applied in rural settings, wasadapted for the first time to an urban context. Thismeant factoring in, among other things, theparticipants’ multiple livelihood activities, limited timeavailability, and competing priorities.A participatory project on the outskirts <strong>of</strong> Lima ishelping an organized group <strong>of</strong> farmers to improve theirquality <strong>of</strong> life and care for the environment bystrengthening the management <strong>of</strong> their crops andlivestock production systems.As metropolitan Lima continues to sprawl further into theRimac river watershed and turn traditional agriculturallands into concrete, urban farmers in the communities <strong>of</strong>Carapongo and Huachipa continually have to deal withthe health, legal and environmental problems thataccompany urban growth. An estimated 20% <strong>of</strong> Limahouseholds are involved in agriculture—backyardlivestock raising or growing horticulture products—withmany <strong>of</strong> these families depending on horticulture as theirmain source <strong>of</strong> income.In an effort to curb the negative effects <strong>of</strong> urbanization,<strong>Urban</strong> Harvest designed and implemented a program thataims to adapt improved technologies to farmers’horticulture production, decrease their use <strong>of</strong> pesticides,and search for new market opportunities for theirAside from adapting the FFS approach to an urbancoastal setting, specifically Lima’s eastern river valley,the approach used in this project was innovative inthe fact that it aimed to find integrated solutions tothe management <strong>of</strong> vegetable crops and not merelyfor the specific problems <strong>of</strong> disease and pest control.The main themes discussed during the FFS sessionsand experiments were land use management,fertilization, management <strong>of</strong> insect pests, watermanagement and irrigation techniques, plantingtechniques, and market access. This helped farmersbecome aware <strong>of</strong> the environmental and healthproblems, market indicators and crop productionissues in their urban environment.The prevalent theme, however, was land use and cropmanagement. Study results highlighted the fact thatthere exists a lack <strong>of</strong> local knowledge <strong>of</strong> urban agroecologiesand <strong>of</strong> pest and disease managementamong producers, which in turn leads to thewidespread use <strong>of</strong> highly toxic pesticides to combatinsect pests and diseases.

Pesticide-related health hazards are particularly relevantin an urban setting because spraying occurs close tohomes and near green spaces used for children’s play.Moreover, pesticide use leads to water contaminationand thus to the marketing <strong>of</strong> contaminated crops.With this in mind, participating farmers were introducedto integrated pest management and soil managementtechniques. Special attention was paid to “soil health”and the use <strong>of</strong> the different composts and manures (cow,chicken, and guinea pig droppings), emphasizing thatplant health depends on soil health.Also discussed were different water and irrigationsystems, including drip irrigation and the use <strong>of</strong>treatment reservoirs with the opportunity foraquaculture and the production <strong>of</strong> clean irrigation water.Specifically, the project involved the construction <strong>of</strong> abackyard reservoir in Carapongo that aims to improvehuman health, the natural environment, and householdincome through the production <strong>of</strong> tilapia fish in thereservoir.Although potato is not normally considered a high valuecrop in Peru, researchers and producers evaluatedpromising native and commercial potato varieties forthe production <strong>of</strong> organically produced cocktailpotatoes for a growing luxury market in Lima.As a result <strong>of</strong> the social learning context <strong>of</strong> FFS,producers in the area have realized the importance <strong>of</strong>grouping together and have formed micro-enterpriseassociations to strengthen their access to existingmarkets and response to new commercialopportunities.Organized farmers in Huachipa, for example, have joinedforces and started selling their organic products to alocal clinic and restaurants, where there is a growingdemand for organic products, in an effort to accessbuyers directly and therefore obtain better prices fortheir ware. According to farmers, direct sales providethem with a consistent, nearby outlet for their productsand at a competitive price. Meanwhile, in Carapongo,the main buyers are families in the area, which simplifiesthe commercialization process and provides immediatereturns for the group.Despite this, project participants have concluded thattapping larger, more pr<strong>of</strong>itable markets for their organicproducts is essential in order for their horticultureproduction to become a sustainable income generatingactivity. So far, both producer groups have linked up withthe Empresa Ecológica Perú, which serves as anintermediary between producers and supermarkets andgreen fairs for the sale <strong>of</strong> organic products. Through thisassociation, producers have completed their first batch<strong>of</strong> deliveries, which included 5 different products.Project leaders attribute a big part <strong>of</strong> the success <strong>of</strong> thisproject to the close collaboration established betweenproducers and the local government. In addition t<strong>of</strong>orming strategic alliances with government institutionsand other non-governmental entities, the project isworking with different actors along the value chain toestablish new market linkages.Projects like these demonstrate the potentials <strong>of</strong> urbanand peri-urban agriculture for poverty alleviation, microenterprisedevelopment, social inclusion, and enhancingfood and nutritional security, among other things.23

Research for a cleaner future:Heavy metal contamination in Kampala24the food consumed in Kampala city is produced byurban and peri-urban agricultural production.The rapid growth (3.5% per year) <strong>of</strong> the city <strong>of</strong> Kampalain recent years makes heavy metal contamination <strong>of</strong>particular concern to urban and peri-urban agriculture.<strong>Urban</strong> ecosystem health is important because <strong>of</strong> thefeedback mechanisms between human actions andpopulation, community and environmental health. Incities in general, accumulations <strong>of</strong> toxic substances,particularly heavy metals, are a major concern in urbanand peri-urban agriculture. Kampala, formerly theBuganda kings’ hunting grounds, has only been a citysince 1961, but there are forgotten former industrial ordumpsites dating from its first half century as a city thatare potential sources <strong>of</strong> soil or water borne contaminants.Kampala City, located in the only urban district in Uganda,has a resident population <strong>of</strong> over 1.2 million (2002 census),but the daytime population is more than twice that size,which implies a heavy amount <strong>of</strong> daily traffic powered byunleaded gasoline moving along major roads, emittingair borne heavy metal particles. About 35% <strong>of</strong> thepopulation <strong>of</strong> Kampala is engaged in farming, about threequarters <strong>of</strong> which are women, and an estimated 40% <strong>of</strong>Since 2002 one <strong>of</strong> the main aspects <strong>of</strong> the work carriedout by <strong>Urban</strong> Harvest and the Kampala <strong>Urban</strong> FoodSecurity and Livestock Coordination Committee(KUFSALCC), a non-governmental, inter-institutionalorganization, has been to study the health impacts <strong>of</strong>urban and peri-urban agriculture in Kampala. In 2004,a study on heavy metal contamination funded by an<strong>International</strong> Development Research Center (IDRC)-AGROPOLIS award was presented at the botanydepartment <strong>of</strong> Makerere University. It is one <strong>of</strong> fewsuch studies on heavy metal pollution from adeveloping country. The main objective <strong>of</strong> the studywas to determine the heavy metal content <strong>of</strong> the air,soil and food crops grown in areas receivingparticulate emissions from motor vehicles in KampalaCity. The soils were analyzed for cadmium (Cd), lead(Pb) and zinc (Zn). Other soil parameters investigatedincluded soil pH, soil organic matter content, textureand macro-element content (phosphorus andnitrogen).After a preliminary study <strong>of</strong> the roadways to see whichwere the most heavily traveled and by what kinds <strong>of</strong>vehicles, the three with the heaviest traffic wereselected. The University <strong>of</strong> Makerere research teamstudied soil samples and the food plants growing fromsome eleven sites, nine <strong>of</strong> them near the most heavilytransited roads and two sites in areas with low trafficdensity to serve as control, taking samples from tenlocations at each site at different distances from theroad. As Grace Nabulo, who headed the team, pointsout: “We also tested to see what kinds <strong>of</strong> food plantswere affected; whether the contamination wasabsorbed or could be reduced by preparation(washing or peeling); if absorbed, what parts <strong>of</strong> theplant—leaf, root, peel, fruit/seed—were affected.” Inaddition, the placement <strong>of</strong> test sites allowed them to

test whether contamination was reduced when cropswere protected from roadway pollution by a housestanding between the road and the field. In order tomeasure airborne lead contamination, test wipes weretaken from window glass to see how the lead contentin the air compared with what was found on leafyvegetables—the window wipes provided a bettermeasure than the plants <strong>of</strong> lead in the air.The toxicity <strong>of</strong> lead, which has no known biologicalfunction in the human body, comes from its ability tomimic other biologically important metals, notablycalcium, iron and zinc. Lead is able to bind to and interactwith the same proteins and molecules as these metals,but the molecules thus formed fail to carry out the samefunctions, such as producing the enzymes necessary forcertain biological processes. The symptoms <strong>of</strong> chroniclead poisoning include neurological problems, amonga long list <strong>of</strong> other pernicious effects. The effects can becarried into the next generation: a woman exposed tolead in her childhood (even with no exposure after that)can pass the lead to her child as an unborn fetus orthrough her breast milk. The link between earlyexposure <strong>of</strong> children to lead and learning disability hasbeen confirmed by multiple researchers and childadvocacy groups. Very young children are particularlyvulnerable to environmental soil Pb through hand tomouth behavior. The four major sources <strong>of</strong> Pb are: (1)the exhaust from vehicles that use leaded gasoline,(2) lead water pipes, (3) industrial emissions and (4)Pb in paint.Cadmium (Cd) and some Cd compounds are listed bythe <strong>International</strong> Agency for Research on Cancer ascarcinogenic. Cadmium is bioaccumulative andpersistent. It is a priority pollutant that should beeliminated, not just reduced. Zinc (Zn) has toxic effectson the environment. It is a component <strong>of</strong> tires, which isreleased as they wear down. Although Zn is an essentialelement for higher plants, it is considered phytotoxic inelevated concentrations, directly affecting crop yieldsand soil fertility.The study found the total lead in soils to be withinacceptable concentrations for agricultural use with theexception <strong>of</strong> three sites, which were the sites rankedfirst, second and third in terms <strong>of</strong> traffic density <strong>of</strong>gasoline powered light vehicles, —heavy vehicles usediesel fuel, which does not contain lead. Total cadmiumin soil was found at concentrations above therecommended maximum for agricultural soil at most<strong>of</strong> the sites. Total zinc in soil was found withinrecommended concentrations at all sites except one.On the other hand, elevated concentrations <strong>of</strong> Pb, Cdand Zn were found in all crops and, in particular, leafyvegetables. Most <strong>of</strong> the heavy metal accumulation wasin the leaves compared to the roots, fruits and tubers.Heavy metal accumulation in leafy vegetables was inthe order <strong>of</strong> leaf > root > peel > fruit/seed. In root cropsthe order <strong>of</strong> accumulation was root > leaf > peel > tuber.The total heavy metal content <strong>of</strong> soils was observed todecrease rapidly with increasing distance from theroads. Accumulation <strong>of</strong> Pb in soils above backgroundlevels took place up to a distance <strong>of</strong> 30 m, after which itbecame constant.Finally, this study found the dominant pathway for Pbcontamination <strong>of</strong> leafy vegetables was from aerialdeposition, while Pb in root crops appeared to originatefrom the soil. Likewise, Zn vegetable contaminationstemmed mainly from aerial deposition. On the otherhand, the major pathway <strong>of</strong> contamination by Cd wasfound to be uptake from the soil, possibly from anabandoned industrial site or dumpsite.Findings and recommendations <strong>of</strong> the research studyare: Roadside farming activities in the city are safest ata distance <strong>of</strong> more than 30 m from the edge <strong>of</strong> the road.Leafy vegetables should not be grown near roadsides,25

26regardless <strong>of</strong> traffic density. Crops where the edible partis protected from aerial deposition, such as corn, pulseslike beans and peas, and some tubers such as sweetpotatoand cassava, are safer for roadside farming, but the peel<strong>of</strong> tubers and the pod <strong>of</strong> beans and peas accumulatehigher Pb contents and should not be used. Thosevegetables that bioaccumulate heavy metals in their skinsshould be peeled. All vegetables should be washedthoroughly in plenty <strong>of</strong> clean water before consumption.Washing was found to reduce the Pb and Cd contents inmany <strong>of</strong> the vegetables studied but had little effect onthe zinc content. If possible, areas other than roadsidesshould be utilized for the growing <strong>of</strong> crops forconsumption. The placement <strong>of</strong> gardens on the far side<strong>of</strong> houses could help to block some <strong>of</strong> the deposition <strong>of</strong>lead, cadmium and zinc. Sheltering crops could helpreduce the amount <strong>of</strong> heavy metals deposited frompassing vehicles. Regulation <strong>of</strong> vehicle emissions andthe introduction <strong>of</strong> unleaded fuel are recommendedas part <strong>of</strong> the long-term solution to this problem.Allocation and monitoring <strong>of</strong> land usage withinKampala could help to reduce the use <strong>of</strong> hazardousareas for agricultural activities.The heavy metal contamination study providedimportant information for two other <strong>Urban</strong> Harvestprojects in Kampala. More knowledge and especiallymore detailed knowledge about heavy metalcontamination early in the urbanization process canbe used to build safeguards into the process andcreate options to mitigate or avoid dangerous impactson environmental and human health.

Dirty secret treasures in NairobiNairobi has passed through many changes since itsfounding a little more than a century ago. Today it isstill a cosmopolitan city known variously as the “GreenCity in the Sun”, the “Safari Capital <strong>of</strong> the World” or the“Place <strong>of</strong> Cold Waters”, although many parts <strong>of</strong> it haveincreasingly become buried under mounds and heaps<strong>of</strong> garbage and a lot <strong>of</strong> the “cold waters” arecontaminated by sewage. About 40% <strong>of</strong> the more than1740 metric tonnes <strong>of</strong> solid waste generated every dayby its approximately 3 million residents gets collectedand disposed <strong>of</strong>. The rest continues to mount up in openspaces, along the roads, the railroad, the river, formingpiles everywhere in most <strong>of</strong> the residential, industrialand commercial neighborhoods, even in the businessdistrict. Like other cities in developing countries, themunicipal infrastructure has not been able to keep pacewith the rapidly growing population. By the mid-1980s,private waste collectors serviced middle and highincome residential neighborhoods, but lower incomeresidents had to find other solutions to the sanitationproblem. About 50% <strong>of</strong> Nairobi residents live below thepoverty line and are concentrated in peri-urban slumareas characterized by limited amenities and unhygienicliving conditions. By the early 1990s there were a fewsmall-scale community-based composting groups, whoutilize a small amount <strong>of</strong> the accumulation <strong>of</strong> manurefrom the many animals being raised for the local foodmarket.<strong>Urban</strong> Harvest conducted a study in partnership with<strong>International</strong> Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), WorldAgr<strong>of</strong>orestry Center (WAC), both <strong>of</strong> which are centers<strong>of</strong> the Consultative Groups on <strong>International</strong> AgriculturalResearch (CGIAR), Kenya Agricultural Research Institute(KARI) and Kenya Green Towns Partnership Association(KGTPA), which is an NGO. The study illustrated genderinvolvement in management <strong>of</strong> municipal organic solidwaste (MOSW) for urban and peri-urban agriculture aswell as the different aspects <strong>of</strong> waste management aslivelihood strategies. The data was compiled from asurvey conducted in 2003-2004 on management <strong>of</strong>organic waste and livestock manure for enhancingagricultural productivity in urban and peri-urbanNairobi. The objectives <strong>of</strong> the study were to make aninventory <strong>of</strong> community based organizations involvedin organic waste management for urban and peri-urbanagriculture (UPA), document the existing compostinggroups in Nairobi, analyze composting managementtechniques, model rural-urban nutrient movements andlink stakeholders in UPA.In January 2005 the final stakeholder workshop was heldto discuss the results <strong>of</strong> the study <strong>of</strong> waste recycling inNairobi, with a special focus on the use <strong>of</strong> manure andorganic residues in agriculture. Attending the workshopwere representatives <strong>of</strong> the implementation team listedabove plus staff from the Nairobi City CouncilDepartments, national government and civil societyorganizations who are involved in and concerned withthe management <strong>of</strong> urban wastes. It was also a way <strong>of</strong>familiarizing them with the specific objectives <strong>of</strong> theoriginal project, making them aware <strong>of</strong> thecharacterization <strong>of</strong> ecological exchanges <strong>of</strong> nutrientsamong different sectors and geographical areas <strong>of</strong> thecity and the value chain involved in economic27

28exchanges <strong>of</strong> different kinds <strong>of</strong> wastes between rural andurban areas.Waste is a relative term. Although it refers to somethingthat is useless or worthless, it must be borne in mind thatwaste—like beauty—is in the eye <strong>of</strong> the beholder. <strong>Urban</strong>agriculture plays a significant role in urban environmentalmanagement through waste recycling. There are a lot <strong>of</strong>nutrients in urban organic waste (carbon, nitrogen,phosphorus and potassium). Only one percent <strong>of</strong> organicwaste in Nairobi is used for production <strong>of</strong> compost foruse as a bio-fertilizer, another use is for animal feed,particularly kiosk and restaurant waste for pigs and goats.Inorganic waste (plastics) can be used to make usefulproducts: hats, bags and baskets, ro<strong>of</strong> tiles, fence posts,cages for small farm animals and containers for compost.Cardboard and packaging can be used for buildingmaterials, oily milk containers and some cardboard areused for fuel. Clearly there is an opportunity here toincrease income from both waste and more efficientfarming and to contribute to a cleaner, healthier localcommunity. This type <strong>of</strong> recycling helps solve anenvironmental problem while providing income for theurban poor.<strong>Urban</strong> agriculture also plays a significant role in wastewaterrecycling through irrigation. This opportunity for urbanwaste recycling has not been exploited due to lack <strong>of</strong> spacefor waste recycling activities and absence <strong>of</strong> appropriatepolicy on waste management. <strong>Urban</strong> agriculture also helpsput idle urban land into productive use.Problems identified which inhibit successful recyclinginclude: (1) insecure access to land for composting, poorgroup management leading to internal conflicts, whichprevents taking advantages <strong>of</strong> economies <strong>of</strong> scale inwaste handling and processing; (2) declining groupmembership due to the still underdeveloped compostmarket and the hard work involved in compostproduction, especially considering the onlytransportation used is the wheelbarrow and (3) atendency to resort to traditional compostingtechniques having rejected newly introducedtechniques.Research on the chemical composition <strong>of</strong> differentcompost sources being used in Nairobi indicated thatthe quality is generally high and there is potential forgreatly increasing the quantity produced. Studies <strong>of</strong>residue markets described a complex network <strong>of</strong>nutrient flows linking rural and urban areas: someurban livestock producers export their surplus fodderto rural areas, while others use compost they haveproduced for their own crops. There is also cocomposting<strong>of</strong> local materials (mixing <strong>of</strong> manure andvegetative residues), which is comparable to what isdone in rural areas. Half <strong>of</strong> the livestock producers usetheir manure for crop production and some sell or giveit away. However, a most disturbing finding was thatup to 80% <strong>of</strong> manure is dumped or burned in publicareas. This represents a large economic loss toagricultural producers and a high potentialenvironmental and health cost to the city.Intriguingly, while urban manure is mostly considereda nuisance, rural manure from Maasai cattle herders ispart <strong>of</strong> a flourishing trade, some sold to peri-urbanvegetable producers and urban nurseries, but mostlytraded on through the city to rural producers in otherparts <strong>of</strong> the region as far as 300 km away. Compostingis not a common practice, which probably accountsfor the high price <strong>of</strong> compost compared to manure.The study found that compost producers, who usuallyadvertise and trade their product on site, are unfamiliarwith marketing strategy and opportunities whilepotential customers are unaware <strong>of</strong> compost sourcesand its high quality. Better marketing skills anddiffusion <strong>of</strong> knowledge could transform this “hiddenresource” into a major source <strong>of</strong> income, earnings andsavings for compost makers and growers alike.

The chaotic state <strong>of</strong> solid waste management servicesin Nairobi is attributed to insufficient funds, insufficientequipment and outgrown institutional andorganizational arrangements. Increasing incomes andsolving environmental problems through recycling andcomposting can be components <strong>of</strong> a systematic,integrated approach to a healthier Nairobi basically byrecognizing and utilizing the valuable resources that arequite literally at their doorstep.29Rural-urban manure and compost markets in amd around Nairobi

Improving the quality<strong>of</strong> irrigation water in Lima30the irrigation canals themselves. This can be a source<strong>of</strong> ill-health for urban consumers and acts as adisincentive to buy local produce. <strong>Urban</strong> Harvest, aspart <strong>of</strong> its collaboration program with themunicipalities in this zone, made a study <strong>of</strong> the level<strong>of</strong> contamination <strong>of</strong> irrigation waters, soils andvegetables, and has worked with local residents tohelp them find a low-cost solution to their problem.Using contaminated water for irrigation is just anotherfact <strong>of</strong> life for the majority <strong>of</strong> urban and peri-urbanproducers in Lima’s Eastern Cone, which produces 35percent <strong>of</strong> the fresh vegetables (lettuce, beets, turnips,cabbage, celery, sweet basil and herbs), as well as a largenumber <strong>of</strong> the small meat animals (chickens, ducks, guineapigs and pigs) consumed daily in Lima. The miningindustry straddles the upper watershed <strong>of</strong> the river thatsupplies most <strong>of</strong> the water for this desert valley, wherethis element is scarce and domestic waters are not treatedbefore being emptied into the river and even directly intoThe Rimac, like most <strong>of</strong> Peru’s coastal rivers, begins atmore than 5100 meters above sea level in the highAndes. Fed by glaciers and seasonal rains, it travels over204 km to cover the 145 km from its source to the sea,passing through a large number <strong>of</strong> crystalline lakesand mining areas in the highlands before it dropsdown to cross the coastal desert. The dry season riverlevel can be very low for as many as nine months <strong>of</strong>the year but the river turns into a raging torrent whenthere are heavy rains in the highlands. Human andenvironmental health risks have long been presentfrom heavy metals leaking from tailings dams <strong>of</strong>operating and abandoned mines into the waters <strong>of</strong>the upper watershed, and in more recent years by theuntreated sewage and refuse dumped into the riverin increasing quantities by the fast-growingpopulation as one gets closer to Lima. Cities locatedat the mouths <strong>of</strong> large rivers all over the world areconfronted with over-enrichment <strong>of</strong> nutrients,contamination by pathogens and toxic chemicalsubstances that adversely affect the ecosystem andpublic health. Lima is no exception.In order to assess the health risks, two types <strong>of</strong> datawere collected and analyzed: secondary data, whichwere collected over a seven-year period by two stateagencies responsible respectively for water andhealth; and primary data, which came from extensivesampling and analysis <strong>of</strong> the waters at differentlocations along the river and irrigation canals, <strong>of</strong> thesoils in the irrigated fields and <strong>of</strong> the vegetables

themselves, both recently harvested and after washingin the irrigation canals. The good news is that the heavymetals cadmium, lead and chrome are no longer much<strong>of</strong> a problem, due to increased control <strong>of</strong> mine tailingsin the upper watershed. Available cadmium assimilatedby plants comes from the parent soil and not frommining activity and can be bioaccumulated at riskylevels <strong>of</strong> foliage plants. There is no evidence <strong>of</strong>bioaccumulation <strong>of</strong> lead and chrome in vegetables.Arsenic is found to be above permissible limits in someplaces. The highest concentration is in huacatay, anaromatic herb <strong>of</strong> the marigold family, used extensivelyin Peruvian cuisine, but in such small quantities that it isultimately considered a low health risk.31The bad news, however, is the alarming amount <strong>of</strong>Escherichia coli bacteria and parasites present in thewater, which is now considered the highestcontamination risk for agricultural activity in the RimacValley. Sometimes the fecal coliform count was morethan five thousand times the maximum permissiblelimits (MPL) for water used to irrigate garden vegetables.It was found that 30% <strong>of</strong> the garden vegetables in oneneighborhood and 70% in two others are over the MPL,making them unfit for human consumption. More than97% <strong>of</strong> the samples <strong>of</strong> irrigation canal water taken inthese three sites exceed the MPL for wateringvegetables. The irrigation canals <strong>of</strong>ten contain thehighest degree <strong>of</strong> contamination and are used to washclothes, for bathing and to wash vegetables for market.Of the vegetables that tested clean at harvest, 38%became contaminated when washed with water fromirrigation canals. Latrines are sometimes installed rightover irrigation ditches and the agricultural fields alsoserve as public latrines, adding a further source <strong>of</strong>contamination.The long-term solution to this problem is the provision <strong>of</strong>sanitation systems for the settlements along the river, butshorter-term mitigation measures are urgently needed.In response to the concerns <strong>of</strong> local producers, <strong>Urban</strong>Harvest coordinates an alliance with the PanAmericanHealth Organization and the PanAmerican Center forSanitary Engineering and Environmental Sciences (OPS-CEPIS), the Centro de Estudios de Solidaridad con AmericaLatina (CESAL), the Rimac Irrigation Users’ Board (JUR), theMunicipality <strong>of</strong> Lurigancho-Chosica and producers fromthe zone with the financial support <strong>of</strong> the NationalInstitute for Agricultural Research (INIA)-Spain, the MadridCommunity and the <strong>International</strong> DevelopmentResearch Centre (IDRC)-Canada, which has installed asmall 185 ft 3 pilot reservoir to treat irrigation water. Waterenters the reservoir from the irrigation canal and is leftstanding for at least ten days, during which time thebacteria are eliminated through aerobic chemicalprocesses and parasites are eliminated throughsedimentation. As part <strong>of</strong> the pilot study, water from thetreatment process was compared with untreated riverwater as sources <strong>of</strong> irrigation for vegetables.The results showed that the reservoir has cleared 98percent <strong>of</strong> bacteria and eliminated all parasites from theriver water. When radish and lettuce were tested forcontaminants, those planted in treated water had up to

3297 percent less bacteria (well below permissible limits)while parasites were practically absent in both crops. Tomaintain this level <strong>of</strong> sanitary quality a reservoir <strong>of</strong> 700m 3 built on an area <strong>of</strong> about 1000 m 2 is required perhectare. If the reservoir is complemented with a technifiedirrigation system <strong>of</strong> multiple floodgates the amount <strong>of</strong>water required to irrigate fields can be reduced by 50%.Apart from the cost <strong>of</strong> the land, the cost <strong>of</strong> a 700 m 3reservoir is about S/.4,5000 (US$ 1,360), which goes up toS/.17,770 (US$ 5,538), depending on the quality <strong>of</strong> thewaterpro<strong>of</strong>ing geomembrane liningliner.To explore alternative economic opportunities, fish(tilapia) production in the reservoir is being assessed.Projections <strong>of</strong> potential net earnings from sale <strong>of</strong>fingerlings and mature fish are S/ 1750 (US$ 555). Inaddition to this benefit, irrigation with reservoir waterappears to have had a beneficial effect both on rate<strong>of</strong> emergence and growth and on the uniformity <strong>of</strong>the crop, with higher percentages <strong>of</strong> marketableproducts available sooner than with use <strong>of</strong> river water.This difference is still being evaluated. The smallreservoir has been shown to have multiple benefits,and is replicable in the area. Working with localproducers, <strong>Urban</strong> Harvest is therefore in the process<strong>of</strong> implementing other reservoirs with the capacity<strong>of</strong> irrigating up to 70 hectares with clean water.

Introduction to stakeholderand policy dialogueUnlike agriculture in rural areas, crop production orlivestock raising in and around cities is enmeshed in acomplex web <strong>of</strong> policies, regulations and competingstakeholder interests which can restrict, constrain andsometimes outlaw the practice. This adds furtherinsecurity to households already <strong>of</strong>ten suffering food andincome insecurity. Municipal recognition and supportfor safe urban and peri-urban agriculture is an essentialpre-condition for its contribution to urban development.The inclusion <strong>of</strong> a research area on stakeholder andpolicy dialogue seeks to contribute to that goal.A first step to good planning is to define the complexinteraction between different urban systems and toinvolve all the interested stakeholders in a participatoryprocess <strong>of</strong> consultation. Negative perceptions (justifiedand unjustified) about urban and peri-urban agriculture(UPA), held by the various players in the planning process,must be confronted through a combination <strong>of</strong> targetededucation, demonstration and participation. Also to bediscussed among local stakeholder groups and policymakersare their perceptions <strong>of</strong> the city they live in,appropriate activities to take place within the city andhow to address the real needs <strong>of</strong> community members.To build understanding and collaboration throughdialogue at municipal and national levels, <strong>Urban</strong> Harvesthas developed a stakeholder dialogue model involvinga multi-agency committee on urban food security andagriculture with participation by municipal authoritiesto oversee research and development interventions andto facilitate policy change. Platforms for dialogue andjoint activities for building awareness have beenestablished, with the inclusion <strong>of</strong> irrigation committeesand women’s community kitchens in Lima, schools inKampala, non-government organization (NGO)networks in Nairobi and Nakuru and flower tradergroups in the Philippines. A good example <strong>of</strong> this workis in Kampala where the City Council <strong>of</strong> Kampalaundertook a participatory consultation withstakeholders to make major revisions to city ordinancesto legalize agricultural activities for the first time. Cityplanning should incorporate an understanding <strong>of</strong>household food security and nutrition conditions,agricultural research and economic forces. Theintegration <strong>of</strong> UPA requires going beyond traditionalplanning approaches. In most <strong>of</strong> the developing world’scities, too little is known about the actual extent to whichurban and peri-urban areas are used for agriculturalpurposes. Also, little is known about the spatialdistribution <strong>of</strong> urban agriculture in the cities and thechange in this distribution over time. Tools such asGeographical Information Systems (GIS) can increaseour understanding <strong>of</strong> UPA in such areas.33