FOCUS ON THE AMERICAS - International Press Institute

FOCUS ON THE AMERICAS - International Press Institute

FOCUS ON THE AMERICAS - International Press Institute

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Above: A man wears tape over his mouth to protest the killing of 23-yearold<br />

journalist Sardasht Othman in Sulaimaniyah, 160 miles northeast of<br />

Baghdad, Iraq, May 12, 2010. (AP)<br />

led invasion, it is two more than last year,<br />

and six too many.<br />

Since the crackdown that followed presidential<br />

elections in June 2009, the media in<br />

Iran remain not free. Many journalists have<br />

been forced to flee the country. While some<br />

journalists were released, others were jailed<br />

without charge and dozens remained behind<br />

bars. In 2010, several bloggers and reporters<br />

who were tried in court received<br />

years-long sentences for “propaganda” or<br />

“insults”. Canadian journalist Maziar Bahari,<br />

who was incarcerated for four months in<br />

2009 and later wrote about conditions in the<br />

prison, was sentenced in absentia to 13<br />

years in prison and 74 lashes on national security<br />

and insult charges. Blogger Hossein<br />

Derakhshan, originally detained in 2008, received<br />

a prison sentence of over 19 years, in<br />

September. News media reportedly receive<br />

regular warnings about their work, and<br />

have been ordered not to cover certain opposition<br />

figures. Certain political websites<br />

are blocked or hacked. In an interesting<br />

twist, according to an anecdote in a WikiLeaks<br />

diplomatic cable that was published<br />

toward the end of 2010, President Mahmoud<br />

Ahmadinejad was slapped by the<br />

Revolutionary Guard’s chief of staff, Mohammed<br />

Ali Jafari, for suggesting in February<br />

that to diffuse tension it might be necessary<br />

to allow greater freedoms, including<br />

press freedom.<br />

Media remained tightly controlled in Saudi<br />

Arabia. Over the past few years, journalists<br />

have enjoyed slightly more freedom to report<br />

on formerly taboo subjects including<br />

crime, drug trafficking, employment,<br />

human rights and religious extremism.<br />

Nonetheless, criticism of the royal family or<br />

government policy is generally prohibited,<br />

and even foreign Arab-language news<br />

sources have been censored or taken off the<br />

air in the past, probably in connection to<br />

their reporting. The Internet is filtered for<br />

social and political content, according to<br />

the watchdog Opennet Initiative, and In-<br />

ternet use is closely monitored.<br />

In April, the website of<br />

an Egyptian rights group was<br />

blocked only 15 hours after it<br />

launched, Arabic Network for<br />

Human Rights Information<br />

(ANHRI) reported, and in October<br />

the website of one newspaper<br />

was blocked and its editor<br />

arrested over a misprint<br />

that was promptly corrected.<br />

Thousands of Saudis have<br />

turned to blogs and other online<br />

forums to express themselves,<br />

but bloggers and online<br />

journalists face the threat<br />

of arrest and imprisonment.<br />

The media environment in Yemen worsened<br />

in 2010; President Abdullah Saleh’s<br />

government continued to struggle with a<br />

secessionist movement in the south, an insurgency<br />

in the north, as well as the threat<br />

of the international terrorist group, Al<br />

Qaeda. A year after the creation of a <strong>Press</strong><br />

and Publications Court to deal with press<br />

offences, several journalists were imprisoned<br />

in connection with their work,<br />

banned from publishing or given high<br />

fines. Journalists were reportedly attacked<br />

and had their homes fired upon. In March,<br />

security forces stormed the Sana’a offices<br />

of Al Jazeera and Al Arabiya television<br />

news networks, which were accused by the<br />

government of having distorted news of<br />

violence in the south. In August, at least 25<br />

Yemeni journalists were detained by the<br />

army while attempting to attend a peace<br />

conference called by tribal leaders, who<br />

are very influential. Although later released,<br />

the journalists were then expelled<br />

from the area and were therefore unable to<br />

cover the conference. In August, freelance<br />

journalist and Al Qaeda analyst Abdulelah<br />

Hiden Shaea was detained, a month after<br />

he was abducted overnight by security<br />

forces and questioned about comments he<br />

made to Al Jazeera. In October, Shaea was<br />

charged with “belonging to an illegal network”<br />

and “supporting the al-Qaeda network”.<br />

One journalist was killed in Yemen<br />

in 2010. Mohammed Shu’i al-Rabu’i, 34,<br />

Journalists and bloggers in Syria<br />

continued to be charged as criminals<br />

for their work and held for<br />

long periods without charge.<br />

was shot and killed on February 13 at his<br />

home in Beni Qais, in the northwest of the<br />

country. While working for the monthly<br />

opposition party newspaper Al Qaira, he<br />

had written about the activities of a prominent<br />

local criminal outfit. Despite these<br />

setbacks, the media continue to fight. As<br />

Yemen Times editor Nadia Al-Saqqaf told<br />

IPI in an interview in March 2010, “There’s<br />

only one way for the media to go, and that<br />

is forward. It’s like you’ve come from the<br />

darkness to the light. It’s not possible to<br />

stop the progress that’s happening in the<br />

media. Only it makes the journalists<br />

stronger and angrier.”<br />

On August 3, the first Lebanese journalist<br />

since 2006 was killed. Assaf Abu Rahhal,<br />

who worked for Al-Akhbar newspaper, was<br />

killed during clashes between Israeli and<br />

Lebanese forces in South Lebanon. As IPI<br />

learned during an October 2009 mission to<br />

the country, the Lebanese media are still the<br />

most diverse and vibrant in the Arab world;<br />

on the other hand, criminal defamation and<br />

other charges continue to plague journalists,<br />

in part because of the strong sectarian<br />

affiliation of many news houses. In March<br />

2010, both the editor and the director of Al<br />

Adab magazine were fined U.S.$4,000 each<br />

for libeling Fakhri Karim, an Iraqi publisher<br />

and adviser to the Iraqi president, ANHRI<br />

reported. Since the murder of two prominent<br />

journalists – Samir Kassir and Gebran<br />

Tueni – in 2005, self-censorship in the<br />

media has been exacerbated because of the<br />

lack of clarity on where “red lines” lie. In<br />

2010, May Chidiac, an LBC anchorwoman<br />

who narrowly escaped death in a car bomb<br />

attack the same year, was named an IPI<br />

World <strong>Press</strong> Freedom Hero.<br />

Journalists and bloggers in Syria continued<br />

to be charged as criminals for their<br />

work and held for long periods without<br />

charge, and the country remained one of<br />

the worst press freedom environments in<br />

the world. In June 2010, the government<br />

had refused to release journalist Ali Saleh<br />

Al-Abdallah from prison, although he had<br />

completed a two-and-half-year sentence<br />

for disseminating false information. Several<br />

journalists remain in prison or currently<br />

face prison terms for their work.<br />

In Israel, the media are perhaps the freest in<br />

the Middle East. But the Israeli authorities<br />

proved again in 2010 that they will not hesitate<br />

to prevent Palestinian journalists from<br />

covering clashes and protests in<br />

the West Bank and Jerusalem.<br />

Dozens of reporters and photographers<br />

were reportedly assaulted<br />

by Israeli soldiers, or had their<br />

equipment confiscated or damaged.<br />

In May, Israeli forces intercepted<br />

a flotilla from Turkey, resulting<br />

in the deaths of several activists and<br />

the detention of at least twenty journalists.<br />

While the organizers of the flotilla claimed to<br />

be transporting only humanitarian aid, Israeli<br />

officials said that the flotilla was illegally<br />

breaching the Gaza blockade, and that<br />

members of a terrorist-linked organization<br />

were also on board. During the raid, Israel<br />

blocked journalists’ communications, confiscated<br />

footage and equipment, caused<br />

physical harm to many on board and detained<br />

journalists against their will.<br />

Journalists in the Palestinian Territories<br />

again found themselves victims of the ongoing<br />

rivalry between the paramilitary<br />

group Hamas, which controls the Gaza<br />

Strip, and the political party Fatah, whose<br />

officials constitute the Palestinian Authority<br />

and have control of the West Bank.<br />

Journalists in the West Bank, especially<br />

those working for Hamas-affiliated media,<br />

had to contend with assault, arrests and detentions<br />

by security forces. In January, former<br />

Filastin newspaper bureau chief<br />

Mustafa Sabri was arrested and taken into<br />

custody for having allegedly defamed the<br />

Preventive Security Forces. He was released<br />

two months later. In February, Aqsa TV correspondent<br />

Tarek Abu Zeid was sentenced<br />

by a military court to one and a half years<br />

in prison. On July 26, a Hebron court sentenced<br />

a journalist from Shihab news<br />

agency, Abu Arfa, to three months in prison<br />

for resisting the policies of the authorities.<br />

Reporters faced even greater obstacles in<br />

Gaza. A September 2010 study by the<br />

Palestinian Centre for Development and<br />

Media Freedoms (MADA) revealed that in<br />

Gaza journalists lack equipment as a result<br />

of the Israeli blockade, and Israeli<br />

forces prevented newspapers from Ramallah<br />

from entering the Strip. In July, after a<br />

ban on three newspapers from the West<br />

Bank was lifted by the Israelis, the Gaza<br />

authorities nonetheless refused to allow<br />

Al-Hayat Aljadedah, Al-Ayyam and Al-Quds<br />

newspapers into the area. Beginning in<br />

February 2010, English documentary<br />

filmmaker Paul Martin was detained for<br />

25 days, accused of aiding a militant<br />

whom Martin was scheduled to help defend<br />

in court. In September, Hamas was<br />

widely criticized for its closure of the<br />

Palestinian Journalists’ Syndicate.<br />

Although widening access to the Internet<br />

has in some ways expanded the space for<br />

discourse in Egypt, the authorities have reacted<br />

by clamping down on bloggers and<br />

traditional media with restrictive media<br />

and national security laws as well as the<br />

threat and use of force. Egypt has been<br />

under Emergency Law continuously since<br />

the assassination of President Anwar al-<br />

Sadat in October 1981, despite promises<br />

from National Democratic Party leader<br />

Hosni Mubarak to repeal the law. The law<br />

allows the authorities to monitor and censor<br />

the media. While the Internet is not<br />

generally censored or filtered, Web use is<br />

monitored through controls on Internet<br />

cafés, which most users rely on for access.<br />

Critical bloggers face harassment, raids on<br />

their homes, defamation lawsuits, arrest<br />

and long detentions. Bloggers Mosad<br />

Soleiman and Hany Nazeer have reportedly<br />

been in jail since 2008 on repeatedlyrenewed<br />

detention orders, although they<br />

have not yet been tried. In 2010, several<br />

journalists were handed steep fines and<br />

prison terms for their work – a particularly<br />

worrying trend as the country moved toward<br />

legislative elections in November<br />

2010 (which were widely criticized as<br />

being rigged) and presidential elections<br />

scheduled for October 2011. Several journalists<br />

were pressured to tone down or stop<br />

producing their work.<br />

<strong>Press</strong> freedom conditions remained bleak<br />

in Algeria in 2010. President Abdelaziz<br />

Bouteflika’s government continues to control<br />

the broadcast media, and exercise pressure<br />

over private publications that rely on<br />

advertising from state institutions. According<br />

to the OpenNet Initiative, Internet use is<br />

regulated through the criminalization of<br />

posting content that offends public order or<br />

morality, and through surveillance of Internet<br />

cafés. In March, the website of Radio<br />

Kalima – Algérie, an independent news<br />

provider, was blocked only two months<br />

after the station launched. Journalists can<br />

be arrested for non-accreditation, as well as<br />

under criminal libel and insult laws, including<br />

laws that explicitly protect the president<br />

and other officials. When convicted, journalists<br />

face imprisonment or steep fines.<br />

Foreign journalists are sometimes denied<br />

entry, or prevented from working once they<br />

are in the country. Two Moroccan journalists<br />

were ordered to stay in their hotel room<br />

for four days in September, and were prevented<br />

from covering conditions in a<br />

refugee camp that houses ethnic Sahrawi<br />

refugees from Western Sahara.<br />

The status of Western Sahara, which is administrated<br />

as part of Morocco, remained a<br />

sensitive subject for the press in that country,<br />

as did the royal family and the sanctity<br />

of Islam. Despite a 2002 liberalization of the<br />

<strong>Press</strong> Law, journalists still face prison terms<br />

of three to five years for defamation, and<br />

can also be imprisoned for other press offences,<br />

including the spreading of “false information.”<br />

Several journalists were sent to<br />

jail for their work in 2010. In February, the<br />

newsmagazine Le Journal Hebdomadaire<br />

was forced to close due to bankruptcy – but<br />

founder Aboubakr Jamai told the Committee<br />

to Protect Journalists in an interview<br />

that the magazine would have been able to<br />

pay their creditors had it not been for orders<br />

to advertisers that they should boycott the<br />

publication. The journal was also set back<br />

financially in 2006, when it was ordered to<br />

pay the equivalent of around U.S.$350,000<br />

in a defamation case. In October, the magazine<br />

Nichane closed because pro-government<br />

organizations refused to advertise in<br />

its pages, the Arabic Network for Human<br />

Rights Information (ANHRI) reported.<br />

Tunisia took the spotlight in early January<br />

2011 when massive protests against economic<br />

conditions and corruption resulted<br />

in the flight of former President Zine El<br />

Abidine Ben Ali, who had run the country<br />

with an iron fist for more than twenty<br />

years. At the time of this writing, it remains<br />

to be seen whether the new atmosphere of<br />

press freedom and freedom of expression<br />

will be institutionalized with whichever<br />

government is to come. But observers are<br />

optimistic that whatever the future holds<br />

for Tunisian journalists, it will be brighter<br />

and better than the tight control and outright<br />

persecution that characterized the<br />

media environment for so many years. IPI<br />

participated in a mission to Tunisia in late<br />

April 2010, as part of the Tunisia Monitoring<br />

Group, a coalition of free expression organizations<br />

under the <strong>International</strong> Freedom<br />

of Expression eXchange (IFEX). The<br />

mission found that a lack of judicial independence,<br />

restrictions on freedom of assembly<br />

and the continued censorship of all<br />

media, as well as the physical abuse and<br />

persecution of journalists, posed a material<br />

threat to press freedom. Since the ouster of<br />

former President Ben Ali, several journalists<br />

who were in prison have been released,<br />

and state-controlled media have taken it<br />

upon themselves to change positions and<br />

report freely on the Jasmine Revolution.<br />

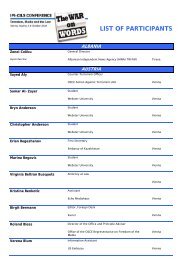

Above: Friends and relatives mourn as they carry the<br />

coffin of Iraqi journalist Riyadh Al-Sarai during his funeral<br />

procession in Baghdad, Iraq, September 7, 2010. (AP)<br />

108 IPI REVIEW<br />

IPI REVIEW 109