Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

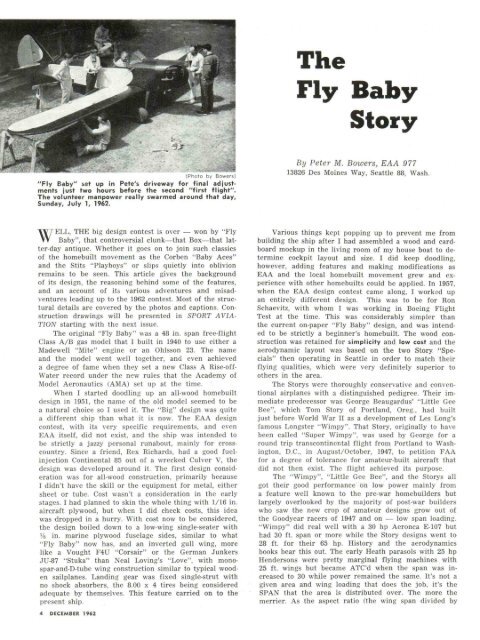

(Photo by Bowers)<br />

"<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>" set up in Pete's driveway for final adjustments<br />

just two hours before the second "first flight".<br />

<strong>The</strong> volunteer manpower really swarmed around that day.<br />

Sunday, July 1, 1962.<br />

WELL, THE big design contest is over — won by "<strong>Fly</strong><br />

<strong>Baby</strong>", that controversial clunk—that Box—that latter-day<br />

antique. Whether it goes on to join such classics<br />

of the homebuilt movement as the Corben "<strong>Baby</strong> Aces"<br />

and the Stits "Playboys" or slips quietly into oblivion<br />

remains to be seen. This article gives the background<br />

of its design, the reasoning behind some of the features,<br />

and an account of its various adventures and misadventures<br />

leading up to the 1962 contest. Most of the structural<br />

details are covered by the photos and captions. Construction<br />

drawings will be presented in SPORT AVIA-<br />

TION starting with the next issue.<br />

<strong>The</strong> original "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>" was a 48 in. span free-flight<br />

Class A/B gas model that I built in 1940 to use either a<br />

Madewell "Mite" engine or an Ohlsson 23. <strong>The</strong> name<br />

and the model went well together, and even achieved<br />

a degree of fame when they set a new Class A Rise-off-<br />

Water record under the new rules that the Academy of<br />

Model Aeronautics (AMA) set up at the time.<br />

When I started doodling up an all-wood homebuilt<br />

design in 1951, the name of the old model seemed to be<br />

a natural choice so I used it. <strong>The</strong> "Big" design was quite<br />

a different ship than what it is now. <strong>The</strong> EAA design<br />

contest, with its very specific requirements, and even<br />

EAA itself, did not exist, and the ship was intended to<br />

be strictly a jazzy personal runabout, mainly for crosscountry.<br />

Since a friend, Rex Richards, had a good fuelinjection<br />

Continental 85 out of a wrecked Culver V, the<br />

design was developed around it. <strong>The</strong> first design consideration<br />

was for all-wood construction, primarily because<br />

I didn't have the skill or the equipment for metal, either<br />

sheet or tube. Cost wasn't a consideration in the early<br />

stages. I had planned to skin the whole thing with 1/16 in.<br />

aircraft plywood, but when I did check costs, this idea<br />

was dropped in a hurry. With cost now to be considered,<br />

the design boiled down to a low-wing single-seater with<br />

Vs in. marine plywood fuselage sides, similar to what<br />

"<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>" now has, and an inverted gull wing, more<br />

like a Vought F4U "Corsair" or the German Junkers<br />

JU-87 "Stuka" than Neal Loving's "Love", with monospar-and-D-tube<br />

wing construction similar to typical wooden<br />

sailplanes. Landing gear was fixed single-strut with<br />

no shock absorbers, the 8.00 x 4 tires being considered<br />

adequate by themselves. This feature carried on to the<br />

present ship.<br />

4 DECEMBER 1962<br />

<strong>The</strong><br />

<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong><br />

<strong>Story</strong><br />

By Peter M. Bowers, EAA 977<br />

13826 Des Moines Way, Seattle 88, Wash.<br />

Various things kept popping up to prevent me from<br />

building the ship after I had assembled a wood and cardboard<br />

mockup in the living room of my house boat to determine<br />

cockpit layout and size. I did keep doodling,<br />

however, adding features and making modifications as<br />

EAA and the local homebuilt movement grew and experience<br />

with other homebuilts could be applied. In 1957,<br />

when the EAA design contest came along, I worked up<br />

an entirely different design. This was to be for Ron<br />

Schaevitz, with whom I was working in Boeing Flight<br />

Test at the time. This was considerably simpler than<br />

the current on-paper "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>" design, and was intended<br />

to be strictly a beginner's homebuilt. <strong>The</strong> wood construction<br />

was retained for simplicity and low cost and the<br />

aerodynamic layout was based on the two <strong>Story</strong> "Specials"<br />

then operating in Seattle in order to match their<br />

flying qualities, which were very definitely superior to<br />

others in the area.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Story</strong>s were thoroughly conservative and conventional<br />

airplanes with a distinguished pedigree. <strong>The</strong>ir immediate<br />

predecessor was George Beaugardus' "Little Gee<br />

Bee", which Tom <strong>Story</strong> of Portland, Oreg., had built<br />

just before World War II as a development of Les Long's<br />

famous Longster "Wimpy". That <strong>Story</strong>, originally to have<br />

been called "Super Wimpy", was used by George for a<br />

round trip transcontinental flight from Portland to Washington,<br />

D.C., in August/October, 1947, to petition FAA<br />

for a degree of tolerance for amateur-built aircraft that<br />

did not then exist. <strong>The</strong> flight achieved its purpose.<br />

<strong>The</strong> "Wimpy", "Little Gee Bee", and the <strong>Story</strong>s all<br />

got their good performance on low power mainly from<br />

a feature well known to the pre-war homebuilders but<br />

largely overlooked by the majority of post-war builders<br />

who saw the new crop of amateur designs grow out of<br />

the Goodyear racers of 1947 and on — low span loading.<br />

"Wimpy" did real well with a 30 hp Aeronca E-107 but<br />

had 30 ft. span or more while the <strong>Story</strong> designs went to<br />

28 ft. for their 65 hp. History and the aerodynamics<br />

books bear this out. <strong>The</strong> early Heath parasols with 25 hp<br />

Hendersons were pretty marginal flying machines with<br />

25 ft. wings but became ATC'd when the span was increased<br />

to 30 while power remained the same. It's not a<br />

given area and wing loading that does the job, it's the<br />

SPAN that the area is distributed over. <strong>The</strong> more the<br />

merrier. As the aspect ratio (the wing span divided by

(Photo by Bowers)<br />

All the tooling needed to assemble the fuselage sides—<br />

a flat work area and some notched two-by-fours. <strong>The</strong>re<br />

are only two scarfed plywood splices in the whole airplane<br />

—visible halfway toward the tail.<br />

the average chord, or span squared divided by wing area)<br />

increases, induced drag, especially at the low speed range,<br />

is decreased. Racers, which don't care about easy landing,<br />

have ratios as low as 3 for good high-speed flight<br />

but the safe-and-slow jobs want higher ratios, at least<br />

over 6. For sailplanes, the A.R. alone is a pretty good<br />

index of performance, with a high for the super-dupers<br />

of 24 to get 40-to-l glide and 16-18 the best structural<br />

compromise. <strong>The</strong>re just aren't any in production any more<br />

with aspect ratios under 10. In modern airplanes, the<br />

Piper PA-15/17 "Vagabond" with A.R. 5.8 and a span of<br />

27 ft. just couldn't compare with the old J-3 "Cub" which<br />

had 35 ft. and an A.R. of 7, and the four-place "Vagabond"<br />

developments, the "Clipper" and the "Pacer" never<br />

really arrived until the horsepower was upped from the<br />

original 115 to an eventual 160.<br />

As a result of all this, the new design ended up with<br />

a span of 28 ft., an A.R. of 6.5, 120 sq. ft. of wing area,<br />

and a good long tail moment arm. Another distinctive<br />

fe; ture of the <strong>Story</strong> was the simple wire bracing of the<br />

two-spar wings to the upper longerons and to a rigid<br />

larding gear. Where the <strong>Story</strong>, in common with the Ryan<br />

ST of 1934 and the Boeing P-26 of 1932, ran the lower<br />

View into the cockpit<br />

showing the finished<br />

forward spar<br />

bulkhead and the<br />

hydraulic brake<br />

master cylinder<br />

mounting. Note the<br />

inboard plywood<br />

covering over the<br />

double bottom longerons<br />

and the forward<br />

bay. <strong>The</strong> diagonals<br />

carry landing<br />

gear loads in the<br />

forward bays but<br />

only serve to stiffen<br />

the plywood skin in<br />

the bays behind the<br />

cockpit. Dural angles<br />

in forward corners<br />

transmit engine<br />

mount loads into<br />

the fuselage sides.<br />

Floorboards rest on<br />

top of the double<br />

longeron structure.<br />

(Photo by Bowers)<br />

(Photo by Bowers)<br />

Two fuselage sides—one with the plywood skin and one<br />

with the temporary gussets. Note the "double" bottom<br />

longerons. Forward upright is birch or oak; other truss<br />

members are spruce.<br />

(Photo by Bowers)<br />

Interior of the fuselage looking toward the nose from<br />

behind the cockpit, showing the corner bows that stiffen<br />

the two wing carry-through bulkheads. Diagonal in front<br />

is strictly temporary.<br />

wires to auxiliary structure behind the wheels, the new<br />

design followed the even earlier style of the Howard<br />

"Pete", Heath "<strong>Baby</strong> Bullet", and the earlier Curtiss<br />

Military Racers by cleaning up the whole under carriage,<br />

using a straight-across axle, and attaching the wires right<br />

to the axle ends. Consideration was given to using struts<br />

above the wings instead of wires, as on the Stits "Playboy",<br />

but the longer span meant that the strut-wing intersection<br />

angle would be very acute and produce a big<br />

interference problem, causing high drag and a significant<br />

loss of lift. It's good to be able to learn by the experience<br />

of others, and since Fred Sindlinger of Seattle<br />

had considerable trouble with his short-span original design<br />

in this area, it was decided to eliminate the problem<br />

by using wires. This decision was backed up by<br />

some of the design articles appearing in SPORT AVIA-<br />

TION and the EAA manuals at the time and the fact that<br />

Vs in. 1 x 19 stranded stainless steel wire, which tests<br />

2,100 Ibs., is a lot cheaper than streamlined steel tubing.<br />

A couple of features that it shared with the 1940 gas<br />

model were the laminated wood wing tip bow construction<br />

and tip shape, and the vertical tail shape with small<br />

underfin. <strong>The</strong>se had practically become a Bowers trademark,<br />

having been used on all my gas models from 1937<br />

to 1949, when I built my last one.<br />

With the new design pretty well firmed up and the<br />

EAA contest now under way, we decided that Ron would<br />

build the new one and enter it as "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong> II" while I<br />

built the original 1951 design as "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong> I". Ron got<br />

started first, and had both fuselage side frames built,<br />

covered with plywood, and joined together when he got<br />

a remote-base assignment and had to give it up. Since<br />

(Continued on next pog«)<br />

SPORT AVIATION 5

"FLY BABY" . . .<br />

(Continued from page 5)<br />

(Photo by Bowers)<br />

Tail surfaces are wire braced and wooden-leg landing<br />

gear is rigid. Fuselage plywood is covered with fabric<br />

at time ship is covered.<br />

I hadn't started mine, I did some serious thinking about<br />

the contest requirements, especially where they stressed<br />

simplicity of construction, easy flying, and low cost. <strong>The</strong><br />

"II" had it all over the "I" here, so I decided it would<br />

be the best one for the contest and bought Ron's fuselage<br />

for what cost he had in it. Since the Cantilever job<br />

was still on the drawing board, there was no point in<br />

calling the existing piece of construction "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong> II",<br />

so it became plain "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>", later "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong> "I" to<br />

provide a more definite designation for FAA paperwork.<br />

Later on, when it was decided to use three different<br />

wing arrangements for versatility, the designation was<br />

expanded to "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong> 1A" for the low-wing design,<br />

"IB" for the same fuselage with a new set of biplane<br />

wings, and "1C" for a strut-braced parasol monoplane<br />

wing fitted to the biplane center section.<br />

While the original design had been worked up for an<br />

85 hp engine, this was no longer available, so 65 was<br />

chosen for the "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong> I" because it was more generally<br />

available and cost less. This was replaced by a Continental<br />

A-75, the A-65 converted, under rather unusual<br />

circumstances. George Loeffers of Seattle had<br />

bought a 65 hp Taylorcraft that needed recover and an<br />

engine overhaul. He decided to convert to 75 hp in the<br />

process, but found out after the job was done that his<br />

ship couldn't take a 75, having been converted up from<br />

50 hp originally. So, since he had a 75 he couldn't use<br />

and I had a majored 65 that he needed, we traded for<br />

the cost of his conversion. For all practical purposes,<br />

though, this engine operated as a 65 while in the ship<br />

because I used a 65 hp metal prop on it and didn't want<br />

to cut it down from its present 74 in. diameter to the<br />

69 in. it was supposed to be for the 75, which picks up<br />

most of the extra 10 hp by turning a smaller prop 200<br />

rpm more than the 65. Actually, the ship was designed<br />

to take up to 85 hp, but I figured that there was no<br />

point in going beyond that.<br />

As work progressed, I found that one of the biggest<br />

problems was shooting down the suggestions of all the<br />

well-meaning visitors who kept trying to improve it to<br />

death by suggesting that "You can get another 5 mph<br />

by cleaning this up", and "Why don't you ...?", and<br />

so on. I had problems with myself in this department,<br />

too. It took real will power to keep in mind that this<br />

was a ship for beginners and resist the temptation to<br />

add features that I would want for my own personal<br />

ship.<br />

Well, as practically everyone finds out sooner or<br />

later on such projects, things went much more slowly<br />

6 DECEMBER 1962<br />

than expected. <strong>The</strong> contest deadline of August, 1960,<br />

got near; "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>" was a long way from completion.<br />

Fortunately, volunteer help from George and Dave Trepus,<br />

who worked at Boeing, became available, and one<br />

of the model building kids in the neighborhood, 12-yearold<br />

Dale Weir, and a couple of high school kids, Jack<br />

Davis and Tony Honsburger, made themselves fixtures<br />

in the shop and soon became indispensable. With only a<br />

couple of months to go, the panic button got pushed hard<br />

and craftsmanship went out the window. For the last<br />

couple of weeks, everyone I could drag into the shop<br />

was put to work, including some local FAA inspectors.<br />

Jim Clark of West Coast Airlines, owner of one of the<br />

<strong>Story</strong>s, handled the powerplant problems and Fxi Rudolph<br />

of G.E. was the paint department.<br />

A word about the covering and coloring — I had<br />

intended to use the colors of the prototype Boeing Jet<br />

Transport, yellow and brown with white trim and wanted<br />

it to be nitrate dope over the Sears-Roebuck Dacron Polyester<br />

Taffeta ($1.37 a yard), but Rex, who is an enamel<br />

enthusiast, talked me into using automotive enamel for<br />

the finish. <strong>The</strong> closest the auto supply store came to the<br />

desired color was "National School Bus Yellow", so this<br />

is what we used. <strong>The</strong> shade "Cordovan Brown" that looked<br />

good on the color chart turned out to be a metallic maroon<br />

(Photo by Bowers)<br />

Tail surfaces are built without jigs. Elevattor spars take<br />

torsion loads so are of box construction; stabilizer spar is<br />

C-section. Note that end ribs are double and boxed with<br />

plywood to resist doped fabric tension. Ribs are V* in.<br />

plywood with V* in. sq. cap strips and leading edges are<br />

covered with .016 in. hardware store aluminum.<br />

on the airplane, but didn't look at all bad. Rudy really<br />

threw the stuff on as time ran out, and we didn't bother<br />

with the white trim. Art Schultz of the Boeing art department<br />

took a short cut on the white fuselage numbers and<br />

outlined them with black 1/16 in. chart tape sealed with<br />

clear plastic spray. This tape held up fine for over a year<br />

and a half in the weather.<br />

With only a week to go before the date of departure<br />

for Rockford, panic really went into high gear. Other<br />

contestants seemed to be having the same problems, for<br />

the judges cut the required 50 hrs. of flight time down<br />

to 25, and then took to phoning Hie various ones to<br />

find out if they'd even have their ships finished in time.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re was serious consideration given to postponing for<br />

another year, but at the last minute it was decided to<br />

have it as scheduled.<br />

<strong>The</strong> test hop for "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>" was scheduled for Wednesday,<br />

July 27, 1960. Needless to say, work carried right<br />

through from the time I got home from Boeing Monday<br />

night, all through Tuesday when I took sick leave, and<br />

all through the night and into Wednesday morning when<br />

we loaded the ship on a glider trailer and hauled it to<br />

Thun Field, at Puyallup, Wash. This was 35 miles away,

off the airways, and the corner of a triangular test area<br />

that I had asked for and gotten. Ted Smith of FAA<br />

showed up on schedule, made his inspection, and finished<br />

filling out the paperwork. I put 5 gals, of gas in the<br />

tank, since I wanted the ship to be light for the first<br />

flight and to reduce the fire hazard — just in case. This<br />

proved to be a mistake, but only one of several to be<br />

made that day.<br />

Since the freshly-overhauled engine had only three<br />

hours of block time and an hour of running in the ship,<br />

we decided to run it in for another hour while taxi-testing<br />

the ship and trying out the brakes and steering.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re was nothing wrong with this — the later troubles<br />

came from over-anxiety to get into the air and the Go-<br />

Go-Go atmosphere generated by the now sizeable crowd<br />

made up of all the local aero-nuts who could get away<br />

from their jobs. I put on a parachute and taxied out to<br />

the end of the runway. <strong>The</strong> first two hops were to be<br />

low drags down the runway with the wheels just off<br />

the ground to test trim and controllability at low power,<br />

and all went well. On the full-throttle run, "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>"<br />

jumped into the air and then the engine sputtered. I<br />

(Photo by Bowers)<br />

Ribs are band sawed from Vs in. plywood, then fitted<br />

with '/» in. by Vt in. slotted cap strips. All were built by<br />

one person in a single Saturday. Wing tip bows are laminated<br />

from !/e in. J Sfl$p$, and ailerons are carried on Cspar<br />

behind rear wing 'spar. Compression ribs are steel<br />

tubing, one of few tyelded assemblies in the ship, and<br />

drag wires are Va in. 1x19 stranded wire.<br />

set down right away and taxied back past the crowd to<br />

try again. Again it happened, so I cut out further attempts.<br />

Since the ship had been given a fuel flow test before<br />

coming to the field and the engine had worked fine on<br />

the full-throttle demonstration for FAA, we were stumped.<br />

We thought that maybe the fuel line had a restriction<br />

or was a bit too small, so put on another and went out<br />

to try again later in the day. This time the throttle was<br />

advanced more slowly to cut down on acceleration and<br />

backward fuel surge, and things seemed to be going OK<br />

until at 20 ft. altitude at low speed with the nose up, the<br />

engine quit cold. With no power and no speed, there was<br />

nothing to do but hold on tight. <strong>The</strong> impact bent the<br />

axles and the steel axle support plates gouged into the<br />

sides of the wooden landing gear struts. Fortunately, the<br />

prop didn't hit the ground so this was the only damage.<br />

<strong>The</strong> ship was able to taxi back to the line under its own<br />

power.<br />

It was several months, long after I had put in a<br />

shorter and still-larger fuel line, that I found out what<br />

had happened. In looking at a photo taken just before<br />

the first take-off, I noticed that the wire fuel level indicator<br />

that sticks out of the cap of the Piper J-3 fuel<br />

tank was all the way down.<br />

<strong>The</strong> hour of engine running had used up most of the<br />

5 gals, that had been put in and no one, neither myself<br />

(Photo by Bowers)<br />

Joe Roskie puts the final bits of hardware store aluminum<br />

flashing to the leading edge of the right wing before covering<br />

with Dacron from Sears.<br />

« ».<br />

nor a single one of the spectators, pilots all, had noticed<br />

the warning that was there for everyone to see! <strong>The</strong> "preflight"<br />

inspection had been made BEFORE the engine<br />

run, and was not repeated before the flight. <strong>The</strong> lesson<br />

learned, fortunately at relatively low cost, was a double<br />

one — first, don't get in a hurry concerning test<br />

flights, and second, forget the weight handicap and fill<br />

the tank for the first flight. While the tank-to-carburetor<br />

relationship was exactly the same in "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>" as it was<br />

in the J-3 "Cub", the lighter homebuilt had considerably<br />

more acceleration with the same power and the small<br />

amount of fuel aboard surged to the back of the tank,<br />

behind the outlet, so the engine was running only on<br />

what was in the sediment bowl. With higher fuel levels,<br />

there was no further problem, but I did make a rule of<br />

"No take-off below % full" as used on Cessna 140s, etc.<br />

Well, it took a day to straighten out the metal<br />

landing gear parts, add a stiffening fairing to the<br />

straight-across tube axle, make two new wooden V-strut<br />

assemblies, and get it all back on the ship. With a full<br />

tank, the first real flight was highly successful, and "<strong>Fly</strong><br />

<strong>Baby</strong>" was at last ready for Rockford, but with only<br />

an hour and four minutes on it. FAA wouldn't let it go<br />

cross-country with only this, so it got loaded back on<br />

the glider trailer and three of us, Jack, Tony, and myself,<br />

left Seattle on Saturday afternoon. Two days and<br />

(Continued on next page)<br />

(Photo by Victor D. Seely)<br />

Those '/s in. plywood ribs are HUSKY. Note that Pete is<br />

standing on the RIBS, not on the spars! Don't try this<br />

stunt until you get the stabilizing tapes in, or the ribs<br />

will bow sideways and break.<br />

SPORT AVIATION 7

"FLY BABY" . . .<br />

(Continued from preceding page)<br />

(Photo by Bowers)<br />

Cockpit is roomy, and central portion of instrument panel<br />

is removable for service. Powerplant department—controls<br />

and instruments—at left, flight instruments in middle,<br />

and navigation department consisting of one compass at<br />

right. Turnbuckle across the middle is loosened to slack<br />

off the wing wires prior to folding. Removable rear tortledeck,<br />

taken off for this photo, is held on by two<br />

trunk latches and two aligning pins.<br />

nights of straight-through driving got us to Minneapolis,<br />

where we spent a night in an auto court and went on<br />

into Rockford, 2,243 miles from home, on Tuesday afternoon.<br />

Well, all the panic and midnight oil proved to be<br />

unnecessary. Only one other contest ship — Neal Loving's<br />

two-seat pusher — showed up. Since his had even<br />

less time than mine due to fuel flow problems, and we<br />

were both way below the special contest minimum of<br />

25 hrs., the judges called the contest off and postponed<br />

it for two years. However, the judges went over the ships<br />

just for the experience, and evaluated them just as<br />

though the contest was going. Beyond that, both ships<br />

just sat, since they couldn't fly; Loving's in the exhibit<br />

hangar and mine in the tie-down area with the "Live"<br />

homebuilts, where it attracted little attention except for<br />

curiosity about the rigid wooden landing gear. <strong>The</strong> wood<br />

was more controversial than the absence of shock absorbers<br />

and the feature of an old-fashioned straightacross<br />

axle. It really looked crude, too. <strong>The</strong> new wooden<br />

Vs had been built in only two hours, were rough-finished,<br />

and not even painted. Reaction to the gear was mixed,<br />

with both "pro" and "con" comments by Bob Whitticr and<br />

Bob Straub in the 1960 <strong>Fly</strong>-In (October) issue of SPORT<br />

AVIATION. My rebuttal to both appeared in the December<br />

issue.<br />

With the <strong>Fly</strong>-In over, there was nothing to do but<br />

haul "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>" home again and wait until 1962. <strong>The</strong><br />

ship, meanwhile, performed just as it was intended to—<br />

as an easy-to-fly, docile, and forgiving sport plane. Any<br />

doubts that anyone had about the performance of the<br />

landing gear were soon dispelled as the ship was based<br />

at Auburn, Wash., which is a really ROUGH sod field.<br />

Since this is 20 miles from home, and my garage is too<br />

small to take even a ship of the EAA contest dimensions,<br />

I left it there except for a trip to the Boeing Hobby<br />

Show of 1960, where it won a big cup for being the most<br />

popular exhibit after taking second in the "Technology"<br />

category. In its original configuration it logged 114 hrs.<br />

and 20 different pilots had flown it.<br />

In April, 1962, disaster struck. A local pilot who borrowed<br />

it for a cross-country got off course in the mountains<br />

in bad weather and ran out of gas. He spotted a<br />

small pasture, but soon saw that he couldn't make it. He<br />

faced a choice of going through two fences on either<br />

a DECEMBER 1962<br />

side of a sunken road or banging it down with surplus<br />

speed in rough ground and brush short of the fences. He<br />

must have been doing 80 when he banged it down on the<br />

nose, one wheel, and the left wingtip. <strong>The</strong> resulting cartwheel<br />

broke the fuselage in two behind the seat, wiped<br />

off the gear on one side, bent the Taylorcraft L-2 engine<br />

mount sideways, did major damage to the leading edges<br />

of both wings, and broke some drag wires in the left<br />

wing. <strong>The</strong> wingtip bows, laminated up to l'/2 in. thick, did<br />

not break and nothing between the pilot's seat and the<br />

firewall budged in spite of the terrific side load that bent<br />

the engine mount. <strong>The</strong> pilot's increased weight during<br />

deceleration bent the steel tube rudder pedals, and that<br />

was all. He only got one scratch out of it all, and that on<br />

his hand from climbing out through the bushes. A good<br />

shoulder harness installation and the double bottom<br />

longeron construction really paid off here.<br />

This was a fine situation in which to be with only<br />

three months to go until the contest. It was the end of<br />

April before the pieces were all home and things were<br />

set up to start the rebuild. Even then it looked impossible<br />

because of the original gang that had helped build<br />

it, only Dale Weir and myself were available for steady<br />

work. Such others as could be counted on could work<br />

only now and then because of other commitments.<br />

<strong>The</strong> big break came unexpectedly on the first of<br />

May. Harry Higgins, an old Seattle gliding buddy that<br />

(Photo by Dole Weir)<br />

Everything shown here weighs 150 Ibs. (instruments are<br />

installed, but don't show). Here are two horizontal tail<br />

units and landing gear Vs. Turtledeck behind cockpit is<br />

removeable and can be replaced with transparent section<br />

and sliding canopy matched to existing windshield.<br />

Dy tsowersj<br />

Down the homestretch the first time—helped by Dale<br />

Weir, the Trepus brothers, and Ed Rudolph, July 17, 1960.<br />

Ten days later the ship was ready to fly.

(Photo by Dale Weir)<br />

Boeing had transferred to Wichita a few years before,<br />

called up and asked if there were any interesting projects<br />

going on in the shop. It seems that he and several<br />

other Wichita engineers had been transferred temporarily<br />

to Seattle to work on the military TFX proposal. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

were "batching" at an apartment about a mile away and<br />

were looking for something interesting to do evenings.<br />

I told him to come on over, and showed him the pile of<br />

wood in the corner.<br />

Volunteer help is sometimes anything but a blessing,<br />

as many homebuilders know, but that wasn't the case<br />

here. Each of the three principals, Harry, John Aydalott,<br />

and John Berwick, program chairman of Wichita EAA<br />

Chapter 88, had plenty of experience and could be given<br />

a job and then forgotten while they went ahead and did<br />

it, so work whizzed along. <strong>The</strong> ability to get along without<br />

the usual supervision really paid off, for Boeing<br />

shipped me to Wright Field for a week later in the<br />

month. While the loyal troops slaved away in my shop,<br />

I was a real stinker and went down to nearby Yellow<br />

Springs to visit Neal Loving for an evening and kept<br />

him from working on his new contest entry! While other<br />

Wichitans helped occasionally, these three really slaved<br />

away at the job, and had it not been for them, "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>"<br />

could not have made it to Rockford by August.<br />

Some time was saved by not having to tear down the<br />

old engine. Jim Slauson, another Boeing-Seattle engineer,<br />

had a freshly-majored Continental C-75 out of an Ercoupe,<br />

supposedly modified to produce 85 hp, so we put<br />

that in. With the increased power, I put in a new special<br />

16 gal. tank with an inverted pyramid bottom to eliminate<br />

fuel flow problems at low levels and high angles.<br />

<strong>The</strong> work was still a rush against a deadline, and again<br />

craftsmanship went out the window, but there was time<br />

to do better on the coloring and some of the details. <strong>The</strong><br />

white trim got on this time, but the wider black tape<br />

didn't stand up more than a couple of weeks this time.<br />

From the time construction actually got under way<br />

on May 5, 1962, to the first re-test flight on July 1, we<br />

built an entirely new fuselage, made major repairs to<br />

both wings as well as re-tinned the leading edges and recovered<br />

both, built new landing gear vee's and straightened<br />

the old metal parts, built a new tank, built the old<br />

vertical tail onto the new fuselage and recovered it,<br />

Towing gliders is one of the things that "Ply <strong>Baby</strong>" was<br />

designed to do. No more waivers for any but standard<br />

category aircraft after June 28, so this activity is now<br />

made new flat-wrap parts for the cowl and hammered<br />

out the old formed parts, adapted a 90 hp PA-11 "Cub"<br />

engine mount, and repainted the remaining old parts to<br />

match the new, using "Cub Yellow" nitrate dope this time<br />

on more Sears Dacron. <strong>The</strong> only change made as a result<br />

of the 1960 judging was to replace the elevator<br />

push-pull tube, which George Owl didn't like a bit, with<br />

cables. <strong>The</strong> nose was shortened 1 in. and the fuselage<br />

behind the wing lengthened 7 in. to overcome a slight<br />

tendency toward nose-heaviness in the original and to<br />

increase the effectiveness of the horizontal tail, which<br />

had been designed relatively undersize in relation to the<br />

wing area and the existing moment arm length in order<br />

to keep the span short enough for trailering without<br />

having to remove it. Not that control wasn't good — it<br />

just became better. <strong>The</strong>re was no weight change because<br />

the weight saved by removing the long steel tube and<br />

its guides just matched that of the extra length of wood.<br />

<strong>The</strong> fuselage itself was actually a bit lighter because<br />

this time the plywood was honest Vs in. instead of the<br />

old 5/32 in. <strong>The</strong> only other structural change was to<br />

reverse the directions of the cross-fuselage diagonals to<br />

simplify the gusseting work during construction. A big<br />

break came from FAA, which ruled that the repair, actually<br />

about 60 percent new airplane when you count the<br />

engine, mount, and tank, was just that and that the<br />

lengthened fuselage was not considered a major alteration<br />

that had to be proved out by a long flight test program.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re were no test hop troubles this time — one<br />

low-altitude drag down the Auburn runway and then a<br />

maximum-climb take-off.<br />

During the rebuild, several features which the ship<br />

was originally intended to have to increase its versatility<br />

and gain contest points were incorporated, principally<br />

fittings for pontoons and provisions for mounting a separate<br />

set of biplane wings. A glider tow hook had been<br />

standard equipment from the first, but hadn't been used<br />

with gliders because of the wrong prop on the 75 hp engine.<br />

This had been real handy as a tie-down feature,<br />

though, allowing one to prop the plane alone without<br />

chocks, get in the cockpit to complete the warmup, then<br />

pull the release handle and taxi away without getting<br />

out to untie the ship. With the 85 hp engine and a 71-48<br />

climb prop, FAA issued a glider-towing waiver, and on<br />

the first try "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>" pulled a standard Schweizer 1-23<br />

sailplane to 3,000 ft. above a 1,500 ft. elevation gliderport<br />

in 10 minutes in hot July weather. <strong>The</strong> waiver was<br />

rescinded in a few days, however, and towing could not<br />

be demonstrated at Rockford, because the FAA agent got<br />

to the bottom of his IN basket soon after issuing it and<br />

found a directive from Washington which stated that after<br />

June 28, 1962, none but standard category aircraft could<br />

be issued waivers for towing. <strong>The</strong> installation of a pair<br />

of Edo D-990 floats was well under way but couldn't be<br />

completed because of other last-minute problems, but<br />

(Continued on next page)<br />

(Photo by David R. Bowers)<br />

taboo. Even in "Dirty" configuration with no gap covers<br />

or aileron seals, and with "<strong>The</strong> Bomb" aboard, ship towed<br />

standard Schweizer 1-23 sailplane to 3,000 ft. in 10 minutes.<br />

SPORT AVIATION 9

"FLY BABY" . . .<br />

(Continued from preceding page)<br />

"<strong>The</strong> Bomb", a streamlined suitcase that everyone thought<br />

was an auxiliary fuel tank, was completed by Jim Weir,<br />

Dale's dad, and painted to match the ship. <strong>The</strong> interchangeable<br />

transparent rear deck and sliding canopy<br />

that could replace the removable turtledeck and headrest<br />

wasn't completed either, but was shown on the drawings.<br />

Because of the expressed preference for two-seaters<br />

in the 1960 contest, serious consideration was given to<br />

converting to two seats since a whole new fuselage had<br />

to be built, but even with 85 hp, I felt that the added<br />

weight and drag would cut down on the good performance,<br />

especially the low landing speed and baby-buggy<br />

handling characteristics that I felt were the ship's strong<br />

points.<br />

<strong>The</strong> rebuilt bird, sometimes called "New <strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>",<br />

to indicate its "After-Crash" status, really looked like a<br />

new machine because it also had a new registration number.<br />

Back in 1960, I had asked for N3PB to indicate my<br />

third homebuilt (the other two were gliders), but N13P<br />

was what FAA Registration Branch at Oklahoma City<br />

came up with. It arrived a few days before the first<br />

flight, so I put it on the ship and filled out the papers<br />

and sent them in. A few months later, I got a letter,<br />

wanting to know where the affidavit was for the small<br />

number. It seems that to get one these days you have to<br />

have the local FAA agent certify that your ship is too<br />

small to take a bigger one. Since this obviously wasn't<br />

Black Sunday, April 15, 1962. A fine situation for a contest<br />

date. In spite of the look of total destruction, pilot<br />

who ran out of gas didn't get hurt, and ship was rebuilt<br />

in seven weeks.<br />

true, and I wouldn't ask Ted Smith to write fiction for<br />

me, I didn't send in an affidavit. I did ask if I could<br />

keep the number, since it was already on the ship —<br />

with enamel yet — and was already on the books in the<br />

local FAA Office, the State Aeronautics Commission,<br />

the County Tax office, and a few other places, all of<br />

which would be bothered by a change.<br />

Officialdom said "No". <strong>The</strong> number had only been<br />

RESERVED for me upon my initial application (and deposit<br />

of $10) and could be ISSUED only upon receipt of<br />

the affidavit. I asked to see photostat copies of the affidavits<br />

that got two-digit numbers for a couple of Grumman<br />

"Gulfstream" transports and a new Piper "Cherokee",<br />

all built after this hassle started, but got no reply<br />

to that pitch. I managed to stall this losing battle along<br />

for a year and finally settled for a new "legitimate"<br />

number, N500F. I knew there would be problems with a<br />

number change — as soon as "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>" was seen with<br />

500F on it I received a request from the State of Wash-<br />

10 DECEMBER 1962<br />

"OLD <strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>" on an early flight, August, 1960. Fuselage<br />

has since been lengthened six inches and number<br />

changed to N500F.<br />

ington for the sales tax on the "new airplane" that I now<br />

owned!<br />

That was only one minor problem of several that<br />

were still to come before Rockford '62. Since one of the<br />

main contest requirements was a set of drawings suitable<br />

for building the ship (supposed to be delivered with the<br />

entry blank, not when the ship was delivered. Lots of us<br />

goofed here), I arranged with an illustrator friend in<br />

California to make good professsional quality drawings<br />

from the shop sketches and rough scribbles that I had<br />

turned out, plus construction photos. I also sent him the<br />

original "Preliminary Information" drawings for the 1960<br />

contest that Bob Parks of the Boeing training unit had<br />

turned out. This was in April, plenty of time to get<br />

them done by contest time. Since I was snowed under<br />

with the rebuild from then on, I didn't follow up to see<br />

how he was doing. Finally, in the middle of July, a big<br />

bundle arrived in the mail from his address. It contained<br />

"<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>" drawings all right — the same ones<br />

I had sent! It seeems he had gotten clobbered in an<br />

auto wreck and a friend of his was settling his affairs<br />

and returning the jobs he had.<br />

Well, it took a few more nights of the midnight oil<br />

to turn out a very quickie set of free-hand shop sketches<br />

and type up the step-by-step instructions that went with<br />

them. <strong>The</strong> result met the contest requirements in that<br />

anyone could build a ship from them, but they were<br />

far from "pro" looking. <strong>The</strong>y are not the traditional "Roll<br />

of Blueprints" approach, but a smaller 8*6 x 11 in. docu-<br />

(Photo by Jim Slouson)<br />

Full speed ahead! Five days after the start of rebuilding.<br />

Harry Higgins at the band saw on the left, Joe Roskie and<br />

John Berwick at the wing in the background, Pete ducking<br />

into the open-bottom fuselage, and Dale Weir behind it.

ment with very few flat layouts, mostly perspective<br />

sketches showing various stages of how to fit things<br />

together. Instead of very detailed views of each part, a<br />

single view with a few key dimensions is given, with instructions<br />

calling sometimes for "Fit on Assembly". This<br />

cuts down greatly on having to build to close tolerances<br />

on a bunch of parts where tolerances are not critical<br />

for the parts themselves except where some other part<br />

has to fit. Interchangeability is not a problem here as<br />

on production-line types, so things are simplified by<br />

fitting one part to another at time of assembly. <strong>The</strong><br />

judges seemed to like this approach real well, judging<br />

by their comments in the October issue. <strong>The</strong> only trouble<br />

with the drawings as submitted is that there is only the<br />

one copy, which is not reproducible. So, until I deliver<br />

better-finished reproducibles, they are holding on to<br />

the prize money! That will take several hundred hours.<br />

One of the big lessons learned by all from this contest<br />

is that it takes just as long to turn out a good set of<br />

drawings as it does to build the plane! Jim Morrow, who<br />

has been doing those Fokker triplane drawings for my<br />

SPORT AVIATION articles, is doing "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>" drawings<br />

now, and they will appear in SPORT AVIATION<br />

as well as in the printed plans document. Incidentally,<br />

you can imagine what all this is doing to that poor triplane<br />

project!<br />

<strong>The</strong>n there was a need to fix up another trailer for<br />

the trip to Rockford. In the 1960 contest, the road speed<br />

requirement was only 40 or 45 mph, and both Loving<br />

and myself towed our ships on their own wheels. We<br />

both had trouble with brake drag and serious overheating,<br />

but figured it was a problem that could be licked.<br />

We both had detachable trailer hitches that hooked to<br />

the tail, and "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>" was wired for regular trailer<br />

lights, turn signals, etc., with the main lights in the<br />

wing butts and clearance lights in the wingtips. Hookup<br />

to the car through a jumper. In 1960, the glider trailer<br />

was used just to get it to Rockford. <strong>The</strong> old glider trailer<br />

wouldn't do for this for 1962, so I had to fix up another,<br />

(Photo by Victor D. Seely)<br />

"Bomb" is a ten-inch diameter streamlined aluminum suitcase,<br />

complete with handle, hinged section, and legs. Ends<br />

are spun aluminum and center is built up of flat sheet.<br />

Paint job matches the airplane.<br />

which kept the midnight oil going a few more nights,<br />

since it was mainly a one-man job until Ron got aboard<br />

near the end. Most of the Wichita gang had gone back to<br />

Kansas by this time.<br />

<strong>The</strong> day of departure finally arrived, but the usual<br />

last-minute stuff delayed the start from 8:00 a.m. until<br />

noon. At first, it was just to be Dale and myself, but<br />

one day before we left Rudy was able to come, a welcome<br />

addition since he could help with the driving<br />

because Dale was too young at 14 for a license. However,<br />

Rudy couldn't get off work until 5:00 and we wanted to<br />

get going earlier, so it was arranged that he would hop<br />

an airliner and we'd pick him up at Spokane, Wash., 300<br />

miles east of Seattle. We made it some time after 11:00,<br />

it turned out. Naturally, I had invited disaster by making<br />

a very foolish remark as we started: "Nothing to do<br />

now but drive a car for three days!" Me and my big<br />

mouth!<br />

It seems that the fuel pump, which had always worked<br />

fine when hauling gliders over the mountains, decided<br />

to act up and we couldn't get over the mountains 50<br />

miles east of Seattle. We got turned around and headed<br />

back down the grade to the nearest town that had a<br />

Ford garage. What with our speed — slightly over Washington's<br />

50 mph trailer limit and just at about EAA's<br />

requirement, and the 20-30 knot wind blowing through<br />

the pass, the airspeed of "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>" on the trailer was<br />

around 80 mph when one of the ropes holding the left<br />

wing broke. <strong>The</strong> airstream ripped the wing right off the<br />

fuselage and off the trailer, and the tip dragged along<br />

on the ground. <strong>The</strong> rest of the wing was held off the<br />

ground by the rigging wires, so only half the thickness<br />

of the good husky (thank goodness for that timber —<br />

again!) wing tip bow and the top of the first rib inboard<br />

got ground away before I could stop the car. Why did<br />

the rope break? More rush—rush—rush. Instead of putting<br />

the bolt through the fitting and then tieing to the<br />

round bolt, I tied to the fitting itself, and vibration and<br />

the sharp corner did the rest. <strong>The</strong> next tiedown method<br />

was good for the rest of the trip, including 60 mph towing<br />

in 40 mph direct cross winds, with no further trou-<br />

(Continued on next page)<br />

(HhoTo by bowers)<br />

Landing gear details, showing the wooden V's, shackle<br />

and clevis pin that hold the flying wires to the end of the<br />

axle, and "<strong>The</strong> Bomb". Wires from longerons to midpoint<br />

of axle stabilize axle against bending under flying<br />

loads and serve as sway braces for "<strong>The</strong> Bomb".<br />

SPORT AVIATION 11

"FLY BABY" . . .<br />

(Continued from preceding page)<br />

ble other than worry that the whole rig was going to<br />

blow off the road.<br />

We got a new electric pump in the car (a $50 job)<br />

and headed east again with the damaged ship. After<br />

picking up Rudy, I phoned friends in Spokane, and received<br />

an invitation from Carl Swanson to bring the<br />

ship into his operation, Mamer-Shreck, at Felts Field.<br />

Since it was midnight, we slept in the car and on the<br />

trailer in front of the hangar and moved in as soon as<br />

it opened up in the morning. We scrounged power tools<br />

and material from Mamer-Shreck and from Paul Laudan,<br />

an old glider buddy working for Cessna at the other<br />

end of the field, and got to work by 9:00 a.m. I tackled<br />

the wing repair while Rudy went to work on the fuselage<br />

repair where the wing hinge had ripped out. Poor Dale<br />

was worn to a frazzle running back and forth between<br />

Cessna and Mamer-Shreck in the heat. "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>" was<br />

ready for a test hop at 3:00 p.m., so, with everyone out<br />

to watch, I taxied out. My only worry was for the effect<br />

of the wrinkles in the leading edge of the left wing.<br />

This had inadvertently been covered with SO aluminum<br />

instead of half-hard like the right wing during the rebuild,<br />

and any movement, pressure, or even a dirty look,<br />

it seemed, made a dent. We drilled holes and poked<br />

through to the opposite side with sticks, which got out<br />

the major dings but left most of the lesser ones. As<br />

Using a boat winch to haul the folded "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>" up the<br />

ramps and onto a flatbed trailer. For long hauls, it is far<br />

better for the ship to take the wings off entirely and<br />

cradle them like the wings on a glider trailer.<br />

soon as the wheels were off the ground I was able to<br />

determine that the wrinkles didn't bother the good old<br />

reliable NACA 4412 airfoil. Knowing that "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>"<br />

would perform as well as ever, I held her down and let<br />

the speed build up and made a steep pull-up with steady<br />

climb to 1,000 ft. that they were still talking about when<br />

Dale and I came back through Spokane two weeks later.<br />

Two design features of "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>" paid off here,<br />

and one was mentioned by the judges in their report in<br />

the magazine — the wing hinge was entirely separate<br />

from the flying fittings. If the hinge had been combined<br />

with close-tolerance fittings and primary structure, we<br />

never would have been able to make such a quick repair.<br />

<strong>The</strong> other was the "double longeron" construction<br />

of the fuselage bottom in the cockpit-firewall area. This<br />

localized the damage when the hinge pulled out and left<br />

basic structure all around the hole to attach new skin<br />

to. No Vs in. plywood was available, so Rudy used two<br />

thicknesses of Paul's 1/16 in. glider plywood. Since the<br />

hinge doesn't carry any load except when the wings are<br />

folded, we didn't have to wait for the glue to dry before<br />

12 DECEMBER 1962<br />

(Photo by Dole Weir)<br />

First flight with "<strong>The</strong> Bomb" aboard. No noticeable effect<br />

on performance. Note the open glider tow hook attached<br />

to the tail wheel casting. Whip antenna is for Mitchell<br />

Airboy Senior radio mounted on cockpit floor ahead of<br />

the stick.<br />

making the test flight. Busting up flying machines is a<br />

heck of a way to win construction points in a contest,<br />

but I am sure that the two mishaps, which proved out<br />

the basic ruggedness and simplicity of the structure by<br />

permitting such quick repairs, influenced the judges.<br />

<strong>The</strong> rest of the trip to Rockford was routine, except<br />

that we had to do more driving and less sleeping to make<br />

up the lost day and a half. We arrived on Tuesday again,<br />

but the big difference this time was that "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>"<br />

could fly. <strong>The</strong> first thing to do, of course, was to look<br />

over the opposition. Finding only five other ships was<br />

a big disappointment in one way, but a break in that<br />

it gave "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>" a better chance. As we saw it, the<br />

contest would be between three ships — Tony Spezio's<br />

"Tu-Holer", Leon Tefft's "Contestor", and "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>".<br />

Leon had most of the same basic design concepts that<br />

I had — all wood, low cost, and maximum structural simplicity.<br />

I figured that he might beat me in the judging<br />

on direct comparison of these features. If the judges considered<br />

craftsmanship, he'd come out way ahead, for his<br />

ship was really tops in that department. However, one<br />

look at his wing span convinced me that "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>"<br />

had a colossal flight advantage. He overdid the simplicity<br />

angle by seeking to avoid even the need to make<br />

a scarfed plywood splice. (<strong>The</strong>re are only two in "<strong>Fly</strong><br />

<strong>Baby</strong>"). <strong>The</strong> plywood covered wings were covered with<br />

standard 4 ft. by 8 ft. sheets, giving a total span of 18 ft.<br />

from two 8 ft. panels and the two foot fuselage. "<strong>Fly</strong><br />

<strong>Baby</strong>" had a full 10 ft. more span. With about 15 percent<br />

more airplane, I am sure that Leon would have taken<br />

it. Even his excellent tricycle landing gear, which contributed<br />

to easy handling, couldn't make up for the performance<br />

handicap of the short-span low-aspect-ratio wing.<br />

Tony's ship wasn't directly comparable to "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>",<br />

but it had features enough all its own to be a<br />

serious worry. First off, I figured he'd get a big advantage<br />

in being two-seat, which in view of the preference<br />

for two-seaters in the 1960 contest should overcome<br />

a lot of shortcomings in other areas. I didn't figure that<br />

he'd lost much for having a steel tube fuselage. Wood<br />

was cheaper and in my opinion easier to work with, but<br />

lots of people would far rather have that ironwork around<br />

them. He got a big cost break by using the Lycoming<br />

ground unit engine, and had lots of speed over "<strong>Fly</strong><br />

<strong>Baby</strong>", but with his greater weight and shorter span,<br />

"<strong>Baby</strong>" should take him on easy flying, slow landing,<br />

etc. We figured it would be pretty close, with "Tu-Holer"<br />

and "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>" fighting for first, Leon's "Contestor" a<br />

sure third, Gene Turner's wooden single-seater, very<br />

similar to the original 1951 "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>" concept in both<br />

(Continued on page 14)

G£A/CP/U ARRANGE ME fJr<br />

'FLY BABY" SPECIFICATIONS<br />

Wing span<br />

Length<br />

Height (folded)<br />

Tail span .......<br />

Wing chord ....<br />

Wing area ...<br />

Empty weight . . .<br />

28 ft.<br />

18 ft. 101/2 in.<br />

6 ft. 11 in.<br />

7 ft. 111/2 in.<br />

4 ft. 6 in.<br />

. .... 120 sq. ft.<br />

605 Ibs.<br />

Gross weight ........ 925 Ibs.<br />

Fuel ...... 12-16 gals.<br />

Power ...... 65-85 hp<br />

Cruising speed ...... 110-115 mph<br />

Rate of climb 850-1100 fpm<br />

Construction ........ All wood<br />

Airfoil . . . . . . . NACA 4412<br />

SPORT AVIATION 13

"FLY BABY" . . .<br />

(Continued from page 12)<br />

structure and performance in fourth place, and the<br />

Eaves' folding-wing "Cougar" fifth.<br />

During the conference that the judges had with each<br />

contestant, they told us how they would evaluate the setit-up-to-fly<br />

operation. <strong>The</strong>y emphasized that any number<br />

of people could help, but that the penalty would be proportional.<br />

I had never set up or folded "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>" all<br />

alone, and in fact, had folded it only a couple of times<br />

since the 1960 meet, but figured that points-wise, it would<br />

be best to do it alone. I went to the nearest hardware<br />

store and bought a broomstick. Rudy sawed off the<br />

round end, drilled each end, and presssed in a long<br />

3/16 in. bolt with the head cut off. We then drilled a<br />

3/16 in. hole part way into each wing tip bow so the<br />

broomstick could be used as a no-slip crutch to hold<br />

the wingtip up when the landing wires were slacked<br />

off. <strong>The</strong> first "solo" set-up was the one I did for the<br />

judges, and from getting out of the car, through untieing,<br />

off the trailer, set-up, and ready for flight was 20<br />

minutes. With a bit of practice and less time spent on<br />

explaining details, I could cut it down to 15, I'm sure.<br />

Folding goes much more quickly. Incidentally, to explain<br />

how all those 16 wires on the wing are slacked off without<br />

undoing all the turnbuckles, there is a single turnbuckle<br />

running across the top of the main fuselage bulkhead.<br />

This is slacked off, and then four pins are pulled<br />

where the wires above and below each panel converge.<br />

Well, enough of history. How does it fly? Darn well,<br />

in the opinion of the judges, who seemed to agree that<br />

this was the ship's strong point in spite of flying it in<br />

the "Maximum Dirty" configuration with no aileron<br />

seals or wing-fuselage gap covers, and with "<strong>The</strong> Bomb"<br />

in place. Adding the gap covers reduced landing speed<br />

by 2 mph through improved airflow over the tail and the<br />

aileron seals (plain masking tape) improved the rate of<br />

roll noticeably. Since they had said that anyone who<br />

could handle a J-3 "Cub" would have no trouble with<br />

it, my 18-year-old son David, a student power pilot with<br />

45 hours, 30 in gliders (private license), and 7 l /z each in<br />

Aeronca C-3 and Piper J-3, used the advance copy of<br />

the judges' magazine article to pound me over the head<br />

with until I let him fly it. On his second time up in it<br />

he went over Mt. Rainier at 15,000 ft. and the next day<br />

took it X-C.<br />

Performance numbers don't mean much unless qualified<br />

with supporting information. With the 74-43 prop<br />

on the original 75 hp engine, it cruised 105 mph at 2150<br />

rpm, the engine being effectively a 65 because of the<br />

prop. It has exactly the same cruise speed with the present<br />

85 engine and a 71-48 climb prop turning 2350.<br />

Changing to a 71-51 ups the cruise speed to 115, but<br />

chops over 150 fpm off the rate of climb. With the<br />

71-51 prop, climb from take-off is 1100 fpm at 2300<br />

rpm and 75 mph IAS. Take-off with this prop is real<br />

short, especially if you keep the tail low. I've never<br />

actually measured the run, but it's short enough to please<br />

anyone. You're about 10 feet in the air, or so it seems,<br />

about the time the tail would just be coming up in a<br />

65 hp "Cub" or a Cessna 140. Time to 4,000 ft. is five<br />

minutes, and to 8,000 ft. is 12 minutes. Times were not<br />

taken above that altitude because maximum efficiency<br />

could not be achieved without operating mixture control.<br />

"<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>" has been to 15,000 ft. with both the old engine-prop<br />

combination and the present 85 with climb<br />

prop, and with the latter shown between 300 and 400<br />

fpm on the rate-of-climb indicator at 10,000 ft.<br />

It's hard to get accurate airspeed readings at both<br />

14 DECEMBER 1962<br />

Airborne in the "NEW <strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>" before getting the name<br />

painted on or trying out "<strong>The</strong> Bomb". Main problem in<br />

getting good flight photos near Seattle is lining up available<br />

photographer, camera plane, AND sunny weather!<br />

ends of the scale, so the high speeds were timed over<br />

measured courses while landing speeds were checked by<br />

a car running alongside during landing. <strong>The</strong>re was too<br />

much difference between various airplanes we tried formation<br />

flying with for that to provide any sort of check<br />

at all. Some read higher and some lower for a given<br />

throttle setting on "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>". Landing speed without<br />

the gap covers is 46-48 mph as near as we can determine.<br />

Procedure is to come in a little fast by "Cub"<br />

standards — about 80, over the fence at 70, chop power,<br />

if carrying any, and hold it off with stick until she threepoints.<br />

Too slow an approach and it won't round out and<br />

float, or hold off, but will plop right on. For real short<br />

landings, drag it in nose-high with power, then chop it<br />

and hit the brakes. When traffic in the pattern permits,<br />

I often make power-off 180 deg. side-approach spot<br />

landings in the "<strong>Baby</strong>".<br />

When you are familiar only with "Cubs" and gliders,<br />

the power-off rate of sink seems awfully high — 800-900<br />

fpm, but this is typical of (relatively) small area ships.<br />

To float like a "Cub", a no-flaps plane has to be about<br />

the same size and wing loading as the "Cub". This is no<br />

problem to the low-time and student pilots, or most<br />

others who will listen while you give them a run-down<br />

on the ship and a cockpit check.<br />

Control is good in all axis, and it can be flown hands<br />

off in moderately bumpy air. No trim system is provided.<br />

<strong>The</strong> pilot can slide back and forth a bit, or actually move<br />

the seat, to balance the changing gas load. For big and<br />

little pilots, both rudder pedals and seat can be adjusted.<br />

With two-to-one aileron differential, turn entry<br />

is easy and very little rudder is needed to keep coordinated.<br />

On the other hand, it's a good "rudder airplane",<br />

and when flying with hands off the stick can be put into<br />

turns and brought out again with rudder alone without<br />

getting sloppy. "<strong>The</strong> Bomb" has no noticeable effect on<br />

the flight characteristics, and seems to knock only about<br />

2-3 mph off the cruise speed. A closed canopy would no<br />

doubt add about 5 mph, but I haven't been in a hurry<br />

to finish the one I started since I like the open cockpit<br />

so well. It's quite comfortable, thanks mainly to the big<br />

three-piece windshield. Goggles aren't necessary at all,<br />

although I generally wear a helmet on most flights.<br />

<strong>The</strong>re's plenty of ROOM in the cockpit, too, so you can<br />

bundle up in heavy clothes and still be able to wiggle<br />

around. <strong>The</strong>re's lots of baggage room behind the seat, and<br />

I also carry small stuff on the floor ahead of the stick.<br />

A back-pack parachute cramps things up a bit, so if you<br />

want to wear one, as for aerobatics, I recommend a seat<br />

pack.<br />

(Continued on bottom of page 15)

Fokker Triplane Planning<br />

In this view of the miniature construction model, the<br />

original Fokker Triplane structural configuration is evident.<br />

Simplicity is the keynote in this structure.<br />

IN PLANNING the necessary modifications to adapt<br />

the original Fokker Triplane structure to take a modern<br />

reliable engine and make other desirable changes,<br />

I have found it wise to build models to help work out<br />

proposed designs. <strong>The</strong> accompanying photos show a pair<br />

of miniature fuselage frames made for this purpose. One<br />

shows the essentially original Fokker structure while<br />

the other shows its extensively modified counterpart.<br />

In making these models soldered metal construction<br />

proved better and somewhat faster than the conventional<br />

cemented wooden method commonly used for flying<br />

models. When using a scale of IVfe in. equals 1 ft. 0 in.,<br />

which is very convenient for scaling purposes, it will be<br />

found that regular copper-coated mild steel welding rods<br />

of l /s in., 3/32 in. and 1/16 in. diameter correspond to<br />

1 in., % in., and Vz in. tubing sizes. It was found that<br />

steel rods are better suited to this project than comparable<br />

bronze brazing rods, because the steel conducts the<br />

heat of soldering much less rapidly, thus allowing additional<br />

members to be added to a cluster without the<br />

whole joint springing apart. Since the real purpose of the<br />

model is to better visualize different trussing schemes<br />

it becomes an advantage to be able to remove or add<br />

members at will.<br />

"FLY BABY" . . .<br />

(Continued from page 14)<br />

I haven't done any aerobatics in it, mainly because<br />

I'm no good at them. Only Dave Gauthier has. <strong>The</strong>y looked<br />

good from the ground, and he seemed pleased after the<br />

short time he'd tried it. I'll let a real "pro" have a try<br />

at it and give a report later. As for spins, it's a hard<br />

fight to get it into one, and then it comes out by itself.<br />

Stall is clean, with no tendency to drop either wing. With<br />

the wires, it's easy to rig the wings to a bit of wash-out<br />

so that there is plenty of aileron control through the<br />

stall. Load factor? Jim Wickham ran a stress analysis<br />

as the subject of a Chapter 26 EAA meeting, and it came<br />

up as 7.<br />

So there it is. I'll admit that it's not an airplane to<br />

By John Doyle, EAA 2931<br />

P. O. Box 13, Andover, Mass.<br />

Generally, rods should be snipped to approximate<br />

length with heavy diagonal cutters and then filed to<br />

exact dimensions. It's unnecessary to make rounded<br />

notches at the ends of struts as the solder fills the joint<br />

well, but scarves often have to be filed to shape where<br />

clusters occur. Splices, such as shown in the photos immediately<br />

behind the cockpit where the longeron tubes<br />

telescope into each other, are best accomplished by scarfing<br />

both members and soldering them together before<br />

jig assembly. As in the building of the full-size article<br />

a suitable jig is absolutely necessary to align the members<br />

in proper position while soldering is done. <strong>The</strong><br />

Fokker Triplane example lent itself well to the standard<br />

side-frame type of construction. With a simple line<br />

drawing of the frame tacked to a soft pine board 1 in.<br />

by No. 18 brads were driven along both sides of the<br />

members to hold them in place. Other jigs were found<br />

useful to hold the completed side-frames in relative position<br />

while cross pieces were added.<br />

John Doyle's redesigned Fokker Triplane fuselage points<br />

out the heavy reinforcing of the entire structure, especially<br />

in the forward bays to acccommodate a modern,<br />

reliable engine.<br />

A Weller WD-135 soldering gun gave good results,<br />

using 50/50 wire solder and Nokorode Fluid Flux. Acid<br />

type fluxes should be avoided because rusting will occur,<br />

making resoldering operations difficult. Rosin type<br />

fluxes are also apt to prove unsatisfactory for they generally<br />

do not work well on steel.<br />

please everybody, especially those who have had previous<br />

experience with homebuilts and have built up their<br />

own ideas as to just what they want. I think that those<br />

to whom speed and zip aren't so important will find it<br />

"<strong>The</strong> Mostest" airplane that they can produce for the least<br />

investment of money and labor. Careful notes were kept<br />

on both of these. <strong>The</strong> raw materials in the original ship<br />

cost $375, and the "used hardware" consisting of a majored<br />

engine, used metal prop, instruments, wheels,<br />

brakes, fuel tank, etc., came to $675 for a total of $1,050.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se at average market prices in 1960. Good horsetraders<br />

and scroungers can doubtless cut this down considerably.<br />

Time to build "<strong>Fly</strong> <strong>Baby</strong>" the first time, averaging<br />

out the labor skills involved, was 720 hours, which<br />

works out to about two hours a day for a year. £<br />

SPORT AVIATION 15