Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

HOW PEIRCEAN WAS THE “‘FREGEAN’ REVOLUTION” IN LOGIC? 36<br />

Peirce’s sojourn in Germany in 1883 (see [Hawkins 1993, 378–379, n. 3]); neither is it known whether Schröder directly<br />

handed the review to Peirce, or it was among other offprints that Schröder mailed to Peirce in the course of their<br />

correspondence (see [Hawkins 1993, 378]). We know at most with certainty that Ladd-Franklin [1883, 70–71] listed it<br />

as a reference in her contribution to Peirce’s [1883a] Studies in Logic, but did not write about it there, and that both<br />

Allan Marquand (1853–1924) and the Johns Hopkins University library each owned a copy; see [Hawkins 1993,<br />

380]), as did Christine Ladd-Franklin (see [Anellis 2004-2005, 69, n. 2]. The copy at Johns Hopkins has the acquisition<br />

date of 5 April 1881, while Peirce was on the faculty. It is also extremely doubtful that Peirce, reading Russell’s<br />

[1903] Principle of Mathematics in preparation for a review of that work (see [Peirce 1966, VIII, 131, n. 1]), would<br />

have missed the many references to Frege. On the other hand, the absence of references to Frege by Peirce suggests to<br />

Hawkins [1997, 136] that Peirce was unfamiliar with Frege’s work. 43 What is more likely is that Peirce and his students,<br />

although they knew of the existence of Frege’s work, gave it scant, if any attention, not unlike the many contemporary<br />

logicians who, attending to the reviews of Frege’s works, largely dismissive when not entirely negative, did<br />

not study Frege’s publications with any great depth or attention. 44<br />

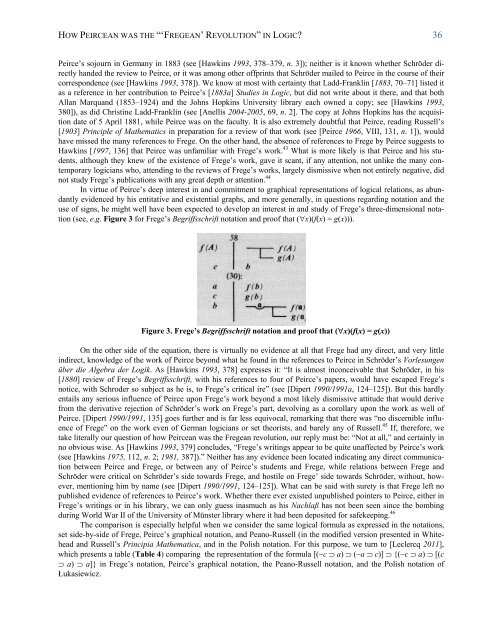

In virtue of Peirce’s deep interest in and commitment to graphical representations of logical relations, as abundantly<br />

evidenced by his entitative and existential graphs, and more generally, in questions regarding notation and the<br />

use of signs, he might well have been expected to develop an interest in and study of Frege’s three-dimensional notation<br />

(see, e.g. Figure 3 for Frege’s Begriffsschrift notation and proof that (�x)(f(x) = g(x))).<br />

Figure 3. Frege’s Begriffsschrift notation and proof that (�x)(f(x) = g(x))<br />

On the other side of the equation, there is virtually no evidence at all that Frege had any direct, and very little<br />

indirect, knowledge of the work of Peirce beyond what he found in the references to Peirce in Schröder’s Vorlesungen<br />

über die Algebra der Logik. As [Hawkins 1993, 378] expresses it: “It is almost inconceivable that Schröder, in his<br />

[1880] review of Frege’s Begriffsschrift, with his references to four of Peirce’s papers, would have escaped Frege’s<br />

notice, with Schroder so subject as he is, to Frege’s critical ire” (see [Dipert 1990/1991a, 124–125]). But this hardly<br />

entails any serious influence of Peirce upon Frege’s work beyond a most likely dismissive attitude that would derive<br />

from the derivative rejection of Schröder’s work on Frege’s part, devolving as a corollary upon the work as well of<br />

Peirce. [Dipert 1990/1991, 135] goes further and is far less equivocal, remarking that there was “no discernible influence<br />

of Frege” on the work even of German logicians or set theorists, and barely any of Russell. 45 If, therefore, we<br />

take literally our question of how Peircean was the Fregean <strong>revolu</strong>tion, our reply must be: “Not at all,” and certainly in<br />

no obvious wise. As [Hawkins 1993, 379] concludes, “Frege’s writings appear to be quite unaffected by Peirce’s work<br />

(see [Hawkins 1975, 112, n. 2; 1981, 387]).” Neither has any evidence been located indicating any direct communication<br />

between Peirce and Frege, or between any of Peirce’s students and Frege, while relations between Frege and<br />

Schröder were critical on Schröder’s side towards Frege, and hostile on Frege’ side towards Schröder, without, however,<br />

mentioning him by name (see [Dipert 1990/1991, 124–125]). What can be said with surety is that Frege left no<br />

published evidence of references to Peirce’s work. Whether there ever existed unpublished pointers to Peirce, either in<br />

Frege’s writings or in his library, we can only guess inasmuch as his Nachlaβ has not been seen since the bombing<br />

during World War II of the University of Münster library where it had been deposited for safekeeping. 46<br />

The comparison is especially helpful when we consider the same logical formula as expressed in the notations,<br />

set side-by-side of Frege, Peirce’s graphical notation, and Peano-Russell (in the modified version presented in Whitehead<br />

and Russell’s Principia Mathematica, and in the Polish notation. For this purpose, we turn to [Leclercq 2011],<br />

which presents a table (Table 4) comparing the representation of the formula [(~c � a) � (~a � c)] � {(~c � a) � [(c<br />

� a) � a]} in Frege’s notation, Peirce’s graphical notation, the Peano-Russell notation, and the Polish notation of<br />

Łukasiewicz.