Central nervous system vasculitis

Central nervous system vasculitis

Central nervous system vasculitis

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Central</strong> <strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong> <strong>vasculitis</strong>Rula A. Hajj-Ali a and Leonard H. Calabrese ba Center for Vasculitis Care and Research and b RJFasenmyer Chair of Clinical Immunology, Departmentof Rheumatic and Immunologic Diseases, ClevelandClinic, Cleveland, Ohio, USACorrespondence to Rula A. Hajj-Ali, Center forVasculitis Care and Research, Department ofRheumatic and Immunologic Diseases, ClevelandClinic, 9500 Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, OH 44195,USATel: +1 216 444 9643; e-mail: hajjalr@ccf.orgCurrent Opinion in Rheumatology 2009,21:10–18Purpose of reviewIn the past decade, primary and secondary central <strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong> (CNS) vasculitideshave been more commonly diagnosed and recognized than previously. With theincreasing awareness of these disorders, it is crucial for the treating physician todifferentiate between causes of CNS <strong>vasculitis</strong> and to recognize their marked clinicaland pathophysiological heterogeneity. This review focuses on the major forms of primaryCNS <strong>vasculitis</strong>, as well as secondary CNS <strong>vasculitis</strong> with emphasis on their clinicalfindings, diagnoses, and treatment.Recent findingsThe proposal of reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndromes (RCVS) as a unifyingconcept for a group of disorders which are characterized by acute-onset severerecurrent headaches, with or without additional neurologic signs and symptoms, andprolonged but reversible vasoconstriction of the cerebral arteries, has been a majorbreakthrough in this field over the past decade. Recognition of this common mimic (i.e.RCVS) has allowed optimal management of a sizable group of patients previouslyconfused with pathologically documented CNS <strong>vasculitis</strong>.SummarySound treatment decisions are based on accurate diagnosis. It is essential for theclinicians involved in the evaluation of patients with CNS <strong>vasculitis</strong> to be aware of itsmimics especially RCVS. This article provides a comprehensive review of CNS<strong>vasculitis</strong> and its differential diagnosis. Furthermore, it touches upon workup andtreatment of CNS <strong>vasculitis</strong>.Keywordsgranulomatous angiitis of the central <strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong>, primary angiitis of the central<strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong>, reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndromesCurr Opin Rheumatol 21:10–18ß 2009 Wolters Kluwer Health | Lippincott Williams & Wilkins1040-8711IntroductionVasculitis that affects the central <strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong> (CNS) isone of the most formidable diagnostic and therapeuticchallenges for physicians. The ischemic symptoms andfindings induced by CNS <strong>vasculitis</strong> may be identical tothose produced by infection, occlusive vascular disease,or malignancy. Adding to the diagnostic challenge is thelack of an accurate and sensitive diagnostic test. Theability of the treating physician to tackle the diagnosticand therapeutic challenges is based on familiarity withthe various clinical syndromes associated with CNS <strong>vasculitis</strong>,the understanding of the nature of the disease, andthe knowledge of its mimics. Fortunately, over the pastseveral years, multiple advances occurred in these areas.This review will summarize the clinical presentations,the differential diagnoses, and the diagnostic and therapeuticmodalities of CNS <strong>vasculitis</strong>.Primary central <strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong> <strong>vasculitis</strong>Broadly, CNS <strong>vasculitis</strong> can be classified as primaryangiitis of the CNS (PACNS) when it is confined tothe CNS and secondary when associated with variousother disorders. Initial reports of PACNS described itas a fatal and progressive granulomatous <strong>vasculitis</strong> andreferred to it as granulomatous angiitis of the CNS(GACNS) [1]. Increasing interest in the disease emergedwith the reports of successful treatment with cyclophosphamideand glucocorticoids. In 1988, Calabrese andMallek [2] proposed the criteria for the diagnosis ofPACNS.The presence of an acquired and otherwise unexplainedneurologic deficit and with(a) the presence of either classic angiographic or histopathologicfeatures of angiitis within the CNS, and(b) no evidence of <strong>system</strong>ic <strong>vasculitis</strong> or any conditionthat could elicit the angiographic or pathologicfeatures.In the 1990s, it was recognized that PACNS is a heterogeneousdisorder with clinical subsets that significantlydiffer in terms of prognosis and therapy. PACNS comprisedifferent subsets including GACNS, and atypical1040-8711 ß 2009 Wolters Kluwer Health | Lippincott Williams & Wilkins DOI:10.1097/BOR.0b013e32831cf5e6Copyright © Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

<strong>Central</strong> <strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong> <strong>vasculitis</strong> Hajj-Ali and Calabrese 11cases. Recently, the term reversible cerebral vasoconstrictionsyndrome (RCVS) was proposed to comprise agroup of disorders characterized by acute onset of headaches,with or without neurologic deficit, and prolongedbut reversible cerebral vasoconstriction. RCVS are confinedto the CNS but has marked clinical and pathophysiologicalheterogeneity than GACNS. Being a majormimic of PACNS, RCVS will be discussed in the sectionof primary central <strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong> <strong>vasculitis</strong>. However, itcannot be overemphasized that RCVS is not a form oftrue CNS <strong>vasculitis</strong>, but rather a group of vasoconstrictivesyndromes.Granulomatous angiitis of the central <strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong>GACNS represents about 20% of all patients withPACNS. It appears to be male-predominant and occursat any age. It is characterized by a long prodromal period,with few patients presenting acutely. Signs and symptomsof <strong>system</strong>ic <strong>vasculitis</strong> such as peripheral neuropathy,fever, weight loss, or rash are usually lacking. Because the<strong>vasculitis</strong> may affect any area of the CNS, its presentationmay vary widely, and no set of clinical signs is specificfor the diagnosis. Signs and symptoms of GACNS aresummarized below:(1) Chronic headaches.(2) Encephalopathy.(3) Strokes/transient ischemic attack (more commonrecurrent).(4) Seizures.(5) Behavioral and cognitive changes.(6) Focal motor/sensory abnormalities.(7) Ataxia.(8) Myelopathy.GACNS may be suspected in the setting of chronicmeningitis, recurrent focal neurologic symptoms, unexplaineddiffuse neurologic dysfunction, or unexplainedspinal cord dysfunction not associated with <strong>system</strong>icdisease or any other process.The characteristic pathologic findings include classicgranulomatous angiitis affecting the small and mediumleptomeningeal and cortical arteries with Langhansor foreign body giant cells, necrotizing <strong>vasculitis</strong>, or alymphocytic <strong>vasculitis</strong>. The inflamed vessels becomenarrowed, occluded, and thrombosed, causing tissueischemia and necrosis of the territories of the involvedvessels.The primary event that elicits the inflammatoryprocess in GACNS remains unknown. It is possible thataltered host defense mechanisms tilt the balance ofthe immune <strong>system</strong> and allow a viral illness to escapethe immune <strong>system</strong>, which sets off the vasculitic process[3–8].Reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndromesBenign angiopathy of the CNS (BACNS) was initiallyproposed as a term to characterize a distinct subset ofpatients with isolated neurologic events, characterized byfemale predominance, acute presentation, reversibleangiographic abnormalities, normal results on spinal fluidexamination, and monophasic course [9]. The term‘angiopathy’ was used because of uncertainty regardingthe nature of the pathologic process affecting the vesselwall and the lack of evidence of blood vessel inflammation.In 2002, Hajj-Ali et al. [10] described dramaticresolution of angiographic abnormalities in series of 16patients within 4–12 weeks without intensive immunosuppressivetherapy. With these data, it became apparentthat the underlying pathophysiologic disorder in BACNSpatients was reversible vasoconstriction rather than <strong>vasculitis</strong>.Further on, the term BACNS evolved into a newterminology referred to as reversible cerebral vasoconstrictionsyndromes. The evolvement in the terminologyto RCVS occurred with the recognition that RCVS comprisea group of diverse conditions, all characterized byreversible multifocal narrowing of the cerebral arteriesheralded by sudden, severe (thunderclap) headacheswith or without associated neurologic deficits and mostimportantly by reversible angiographic findings. RCVSinclude BACNS, Call–Fleming syndrome, postpartumangiopathy, migrainous vasospasm, and drug-induced‘arteritis’ [11 ]. Calabrese et al. [11 ] proposed criticalelements for the diagnosis of RCVS which are summarizedbelow.(1) Transfemoral angiography or indirect computed tomographyangiography (CTA) or magnetic resonanceangiography (MRA) documenting multifocal segmentalcerebral artery vasoconstriction.(2) No evidence for aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage.(3) Normal or near-normal cerebrospinal fluid analysis(protein level

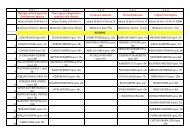

12 Vasculitis syndromesTable 1 Comparison of clinical and diagnostic characteristics of reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndromes and granulomatousangiitis of the central <strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong>RCVSGACNSPatients Female predominant Male predominantHeadaches Acute Chronic, insidiousCSF findings Normal to near-normal AbnormalAngiographyDiffuse areas of multiple stenoses and dilatationinvolving intracranial cerebral arteries, whichare reversible within 6–12 weeksCNS biopsy No vasculitic changes Granulomatous angiitisFrequently normal; otherwise, findings range from singleor multiple arterial cut-off areas, to luminal irregularitiesin single or multiple arteries, to diffuse abnormalities thatare occasionally indistinguishable from RCVS. Theseabnormalities are frequently irreversibleCNS, central <strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong>; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; GACNS, granulomatous angiitis of the central <strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong>; RCVS, reversible cerebralvasoconstriction syndrome. Adapted with modification from [11 ] with permission.the control of cerebral vascular tone seems to be thecritical element in the pathophysiology of RCVS[10,13 ]. In support of this hypothesis is the dearth ofinflammatory changes in CNS pathology of patients withRCVS. Our recent report [13 ] of the largest series ofRCVS to date included 120 patients, 21 of whom underwentbrain biopsies. None of these biopsies revealed anyvasculitic changes. In addition, 98% of the follow-upvascular imaging in this series revealed partial or fullreversibility of the initial vascular abnormalities.The alteration in vascular tone in RCVS may be spontaneousor evoked by various exogenous or endogenousfactors. Exogeneous factors include sympathomimetic orserotonergic drugs [14–20], and direct or neurosurgicaltrauma [21–23]. Endogenous factors include serotonergictumors and uncontrolled hypertension [24].Primary angiitis of the central <strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong>:atypical casesMost PACNS patients present atypically. This subsetdoes not fit the diagnostic features for either GACNS orRCVS, yet these patients demonstrate angiographic orhistopathologic evidence of PACNS. Included in thisTable 2 Clinical and radiographic data in 67 patients withreversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndromeAge 42.5 (range 19–70)Female/male 43/24Precipitating factorNone 25 (37%)Postpartum 5 (8%)Vasoactive substance 37 (55%)Headaches 67 (100%)Recurrent thunderclap 63 (94%)Single thunderclap 3 (4.5%)Recurrent severe 1 (1.5%)Focal neurological deficits 14 (21%)Seizures 2 (3%)Abnormal brain MRI 19 (28%)cSAH 15 (22%)Silent infarct 1 (1%)RPLS 6 (9%)cSAH, cortical subarachnoid hemorrhage; RPLS, reversible posteriorleukoencephalopathy. Adapted with permission from [12 ].group are patients with abnormal cerebrospinal fluid(CSF) findings that preclude a diagnosis of RCVSor those with GACNS-like presentation but withoutgranulomatous features on CNS biopsies. In addition,patients presenting with PACNS at unusual anatomicsites such as the spinal cord or those presenting with masslesions are included in this category.Secondary central <strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong> <strong>vasculitis</strong>Secondary CNS <strong>vasculitis</strong> has been described in associationwith multiple conditions including <strong>system</strong>ic vasculitides,connective tissue disease (CTD), sarcoidosis,infections, and lymphoproliferative diseases. CNS involvementin these setting is frequently a presumed diagnosis,on the basis of radiographic rather than pathologicmodalities.Infectious causes of central <strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong> <strong>vasculitis</strong>Infections affecting the CNS are great mimickers ofPACNS. The infection may be occult and a high degreeof suspicion coupled with the epidemiologic features andthe individual risk factors are important features in theworkup of patients with possible PACNS. In the workupof patients for possible PACNS, it is imperative to searchfor an infectious process through CSF or pathologicexamination, even when a vasculitic process is establishedby pathologic basis. The possibility of infectionswith human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Varicellazoster (VZV), or syphilis should be actively identified.VZV-associated cerebral angiitis affects older age groups[25] and the disease tends to be more localized thanPACNS as well as less severe. The known antecedentinfection with herpes zoster suggests the underlyingcause. Cerebral angiographic findings of segmental, unilateralinvolvement of the vessels in the distribution ofthe middle cerebral artery and, occasionally, the internalcarotid artery are characteristic findings in VZV angiitis.The diagnosis is confirmed by the presence of higherantibodies levels of VZV in the CSF than in the serum orby a positive VZV PCR in the CSF [26].Copyright © Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

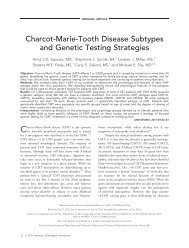

<strong>Central</strong> <strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong> <strong>vasculitis</strong> Hajj-Ali and Calabrese 13Figure 1 Cerebral angiogram of a patient with meningovascular syphilis(a) Magnetic resonance angiography showing basilar artery narrowing with irregularity (long arrow) and abrupt cut off of the right vertebral artery (shortarrow). (b) Angiogram showing narrowed left internal carotid artery. Reprinted with permission from [29].Cerebrovascular disease in HIV is very complex andchallenging. Although a significant number (35%) ofpathologic findings of AIDS-associated CNS diseasedemonstrate encephalitis, leptomeningitis, and/or <strong>vasculitis</strong>,opportunistic infections account for the majority ofthe brain disorder [27]. This demonstrates the complexityof CNS disease in AIDS and the high degree ofscrutiny needed in establishing an accurate diagnosis.Treponema pallidum can invade any vessel in the subarachnoidspace and results in thrombosis, ischemia andinfarction. In the current era, neurosyphilis is most commonin patients with HIV infections [28]. Meningitis andmeningovascular disease are the usual manifestation.This will manifest as an ischemic stroke in a youngperson and can be easily mistaken as PACNS (Fig. 1)[29].Of a special interest is the increasing report of CNS<strong>vasculitis</strong> associated with hepatitis C virus (HCV) withoutunderlying cryoglobulinemia [30]. The detection ofHCV genetic sequences in postmortem brain tissuehas suggested a biologic mechanism that underlies thecognitive findings in patients with HCV infection [31].Other organisms of interest that can affect the CNSinclude Borrelia burgdorferi [32], Bartonella [33], andMycobacterium tuberculosis [34] causing mainly meningitis-likepictures. Interestingly, cysticercosis can involvemiddle-size cerebral vessels in subarachnoid cysticercosiseven in patients without clinical evidence of cerebralischemia [35].Systemic vasculitidesMost <strong>system</strong>ic vasculitides involve the CNS, but are mostcommonly reported in polyarteritis nodosa (PAN), microscopicpolyangiitis (MPA), Behçet’s disease, Wegener’sgranulomatosis [36], and Churg–Strauss syndrome [37].Ascertaining the cause of neurologic dysfunction in<strong>system</strong>ic vasculitides is a multifaceted challenge. Adiligent workup should be sought in these patients toexclude any opportunistic infections, metabolic dysfunction,and drug toxicity. The CNS may be involvedin around 2–8% of Wegener’s granulomatosis patients[36]. Stroke, seizures headaches, confusion, and transientneurologic events such as paresthesia, blackouts, or visualloss are common manifestations [38]. Radiographicallyconfirmed <strong>vasculitis</strong> of the CNS in Wegener’s granulomatosisis rare, because the small vessels (50–300 mm indiameter) are typically below the sensitivity of routineangiography [36].The CNS may be affected in 10–49% of patients withBehçet’s disease resulting either from primary inflammationof CNS tissue or from <strong>vasculitis</strong> with a venouspredominance leading to ischemic stroke [39,40].Connective tissue diseasesCNS involvement in CTDs in not uncommon, especiallyin patients with <strong>system</strong>ic lupus erythematosus (SLE)Copyright © Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

14 Vasculitis syndromes[41 ]. Other CTDs that can involve the CNS includeSjögren’s syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, mixed CTDs,and dermatomyositis. An important consideration in thediagnostic approach to a patient with neurologic dysfunctionin the setting of CTDs is whether the particularclinical syndrome is due to CTD-mediated organ dysfunction,a secondary phenomenon related to infection,medication side-effects, or metabolic abnormalities (e.g.uremia), or is due to an unrelated condition.The most common disorder affecting the CNS in SLEis a bland vasculopathy consistent with small-vesselhyalinization, thickening and thrombus formation [42],and microinfarcts [43]. Sjögren’s syndrome, like Behçetdisease, may mimic multiple sclerosis and present as arelapsing-remitting or primary progressive neurologicdysfunction [44]. Rheumatoid <strong>vasculitis</strong> affecting theCNS is rare and may present with seizures, dementia,hemiparesis, cranial nerve palsy, blindness, hemisphericdysfunction, cerebellar ataxia, or dysphasia [45,46].Miscellaneous disordersAntiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is one of the syndromesthat are highly encountered in the differentialdiagnosis of CNS <strong>vasculitis</strong> [47,48 ]. Thrombotic-relatedevents are the most common APS neurologic manifestation.Seizures, cognitive dysfunction, or psychosis maybe the target of antibody-mediated endothelial damage inAPS [49]. Antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapies arecurrently indicated for APS-related ischemic strokes,but they remain controversial for nonthrombotic neurologicmanifestations.Vasculitis of the CNS has been reported in associationwith Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma andangioimmunolymphoproliferative lesions [50]. The anatomiclesions of the lymphoproliferative disease could bewithin or outside the CNS. Mass lesions, lymphocyticdisease, and spinal cord involvement raise the suspicion oflymphoproliferative disease. Appropriate immunohistochemistrystaining as well as B-cells and T-cellsmarkers should be performed even with the pathologicfinding of angiitis because the presence of vasculiticchanges does not exclude an underlying lymphoproliferativecondition.Other miscellaneous disorders include mitochondrialencephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke syndrome(MELAS), which is a mitochondrial geneticdisorder caused by a point mutation at nucleotide3243 (A3243G) leading to stroke-like episodes beforeage 40, seizures, dementia, and ragged-red fibers inmuscle [51]. Another is the cerebroretinal vasculopathysyndrome, which is an autosomal-dominant retinal vasculopathywith cerebral leukodystrophy leading tostroke and dementias with middle-age onset [52 ].Other miscellaneous conditions include amyloid angiopathyand inflammatory bowel diseases.DiagnosisThe first task of the clinician is to accurately catalogueareas of disease involvement by careful history andphysical examination. The evolution of the differentialdiagnosis and test selection depends on the expectedprevalence of an illness in the population and the physician’sprior experience. The presence of <strong>system</strong>ic features,symptoms outside the CNS, and clues from pastmedical history deviate the hierarchy of the differentialdiagnosis to either <strong>system</strong>ic vasculitides, infectious orvaso-oclusive diseases. There are no laboratory tests thatare diagnostic for CNS <strong>vasculitis</strong>. Acute-phase reactants,such as sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein, areusually normal in patients with PACNS. If serum markersof inflammation are elevated, secondary forms of CNS<strong>vasculitis</strong> should be evaluated. If the history and physicalexamination point to a <strong>system</strong>ic <strong>vasculitis</strong>, testing shouldproceed accordingly. Testing for a variety of infectiousorganisms, such as mycobacteria, fungi, syphilis, andHIV, is warranted in patients presenting with chronicmeningitis. Other serologic tests are indicated if there is ahistory of exposure, such as tick bites in Lyme disease.Evaluation for hypercoagulable states, emboli, and investigationof drug exposure, including over-the-countermedications, are essential in patients who present withacute focal or multifocal disease.CSF analysis is an essential tool in the diagnostic evaluation;CSF analysis is of great value in ruling out infectiousmimics. CSF findings are abnormal in 80–90% ofpathologically documented cases of PACNS. Findingsusually reflect aseptic meningitis, with modest pleocytosis,normal glucose, elevated protein levels, andoccasionally the presence of oligoclonal bands andelevated IgG synthesis. The importance of obtainingappropriate stains, cultures, and serology evaluations toexclude any infectious causes cannot be overstressed,especially in patients presenting with chronic meningitis.Patients with RCVS typically have a normal or near-normalCSF analysis.Neuroimaging studies, such as computed tomography(CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)2, are notspecific or sufficient for diagnosis of CNS <strong>vasculitis</strong>. MRIis a more sensitive diagnostic imaging technique thanCT, except when cerebral hemorrhage is suspected. Thesensitivity of MRI in biopsy-proven cases approaches100% [50,53]. MRI findings include multiple and oftenbilateral infarcts in cortex, deep white matter, or leptomeninges,with or without contrast enhancement [54–56]. Normal MRI of the brain is not infrequent in RCVS.The most common findings in RCVS include infarction,Copyright © Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

<strong>Central</strong> <strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong> <strong>vasculitis</strong> Hajj-Ali and Calabrese 15Figure 2 Cerebral angiography of a patient with reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome at diagnosis (left) and after 1 month ofcalcium-channel blocker therapy (right)Note the multiple areas of stenosis (white arrows) and dilatation in multiple vessels (black arrows) and their resolution after treatment. Reprinted withpermission from [10].particularly in arterial ‘watershed’ and ‘borderzone’regions, parenchymal hemorrhages and small nonaneurysmalsubarachnoid hemorrhages overlying the corticalsurface [21]. In RCVS, brain infarction results from severehypoperfusion distal to severe vasoconstriction, andhemorrhage presumably results from reperfusion injury.Posterior reversible leukoencephalopathy has also beenreported in RCVS [57].Cerebral angiography is a critical modality in evaluatingpatients with CNS <strong>vasculitis</strong>. However, a treating physicianshould be aware of its limited specificity and lack ofquantitative and qualitative codification. The sensitivityof cerebral angiography decreases with the calibre of thevessel, being most sensitive for disease of larger vessels.Moreover, the angiographic findings should be interpretedcautiously, given its poor specificity [58]. Thefindings of alternating areas of vascular constriction andectasia or beading are not specific for <strong>vasculitis</strong>, and thesefindings should be interpreted along with clinical featuresand CSF findings [58,59]. These findings can be encounteredin vasospastic, infectious, embolic, atheroscleroticdiseases, and hypercoagulable states. In pathologicallyproven cases, such as GACNS, the sensitivity of cerebralangiography findings is as low as 10–20% [60]. Cerebralangiogram is not considered the procedure of choice inascertaining the diagnosis of GACNS. However, involvementof multiple vessels in multiple vascular beds (highprobabilityangiogram) raises the possibility of RCVS.These angiographic findings are characteristic of RCVS.More important is the, documentation of reversibility ofthe angiographic abnormalities, along the course of thedisease, which is essential to secure the diagnosis ofRCVS (Fig. 2) [10].Pathologic evaluation of the CNS is usually entertainedin patients with a chronic meningitis-like picture andwhether there is any suspicion for infectious or neoplasticprocess [61]. The procedure of choice is open-wedgebiopsy of the tip of the nondominant temporal lobe withsampling of the overlying leptomeninges and underlyingcortex [50]. Alternatively, directing the biopsy to an areaof leptomeningeal enhancement, when present, mayincrease the sensitivity. Brain biopsy is limited by itslow sensitivity. False negative biopsies can be as high as25% of autopsy-documented cases [62]. Finally, thepresence of <strong>vasculitis</strong> in the biopsy specimen shouldnot preclude performing special stains and cultures foroccult infections that may produce secondary vascularinflammation.TreatmentThe therapeutic guidelines of CNS <strong>vasculitis</strong> are basedlargely on extrapolation from other <strong>system</strong>ic vasculitidesand from experts’ consensus opinion. There are noCopyright © Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

<strong>Central</strong> <strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong> <strong>vasculitis</strong> Hajj-Ali and Calabrese 178 Duna GF, George T, Rybicki L, Calabrese LH. Primary angiitis of the central<strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong>: an analysis of unusual presentations [abstract]. Arthritisrheum 1995; 38 (Suppl 9):S340.9 Calabrese LH, Gragg LA, Furlan AJ. Benign angiopathy: a distinct subset ofangiographically defined primary angiitis of the central <strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong>.J Rheumatol 1993; 20:2046–2050.10 Hajj-Ali RA, Furlan A, Abou-Chebel A, Calabrese LH. Benign angiopathy of thecentral <strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong>: cohort of 16 patients with clinical course and longtermfollow-up. Arthritis Rheum 2002; 47:662–669.11Calabrese LH, Dodick DW, Schwedt TJ, Singhal AB. Narrative review:reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndromes. Ann Inter Med 2007;146:34–44.This is a very comprehensive review of reversible cerebral vasoconstrictionsyndrome. It is highly recommended for the reading physicians. This review tacklesthe diagnosis, differential diagnosis, and treatment of RCVS.12Ducros A, Boukobza M, Porcher R, et al. The clinical and radiologicalspectrum of reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome: a prospectiveseries of 67 patients. Brain 2007; 130 (Pt 12):3091–3101.This is a large prospective series of RCVS patients. This study describes in detailthe clinical and radiologic findings of RCVS as well and treatment and outcomes.The advantage of this study is its prospective design.13 Hajj-Ali RA, Singhal AB, Calabrese LH. Reversible cerebral vasoconstrictive syndrome [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum 2008; 58(Suppl 9):S906.This is the largest series of RCVS reported to date. This study describes clinicalphenotype, radiologic findings, cerebrospinal fluid findings, pathologic findings,treatment, and outcomes of 120 patients with RCVS.14 Singhal AB, Caviness VS, Begleiter AF, et al. Cerebral vasoconstriction andstroke after use of serotonergic drugs. Neurology 2002; 58:130–133.15 Henry PY, Larre P, Aupy M, et al. Reversible cerebral arteriopathy associatedwith the administration of ergot derivatives. Cephalalgia 1984; 4:171–178.16 Le Coz P, Woimant F, Rougemont D, et al. Benign cerebral angiopathies andphenylpropanolamine. Revue Neurol 1988; 144:295–300.17 Raroque HG Jr, Tesfa G, Purdy P. Postpartum cerebral angiopathy: is there arole for sympathomimetic drugs? Stroke 1993; 24:2108–2110.18 Noskin O, Jafarimojarrad E, Libman RB, Nelson JL. Diffuse cerebral vasoconstriction(Call–Fleming syndrome) and stroke associated with antidepressants.Neurology 2006; 67:159–160.19 Nighoghossian N, Trouillas P, Loire R, et al. Catecholamine syndrome,carcinoid lung tumor and stroke. Eur Neurol 1994; 34:288–289.20 Razavi M, Bendixen B, Maley JE, et al. CNS pseudo<strong>vasculitis</strong> in a patient withpheochromocytoma. Neurology 1999; 52:1088–1090.21 Singhal AB. Cerebral vasoconstriction syndromes. Topics Stroke Rehab 2004;11:1–6.22 Wilkins RH, Odom GL. Intracranial arterial spasm associated with craniocerebraltrauma. J Neurosurg 1970; 32:626–633.23 Lopez-Valdes E, Chang HM, Pessin MS, Caplan LR. Cerebral vasoconstrictionafter carotid surgery. Neurology 1997; 49:303–304.24 Kontos HA, Wei EP, Navari RM, et al. Responses of cerebral arteries andarterioles to acute hypotension and hypertension. Am J Physiol 1978; 234:H371–H383.25 Sigal LH. The neurologic presentation of vasculitic and rheumatologic syndromes:a review. Medicine 1987; 66:157–180.26 Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Gilden DH. Varicella-Zoster virus infections ofthe <strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong>: clinical and pathologic correlates. Arch Pathol Lab Med2001; 125:770–780.27 Mossakowski MJ, Zelman IB. Neuropathological syndromes in the course offull blown acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) in adults in Poland.Folia Neuropathol 1997; 35:133–143.28 Merritt HH, Adams RD, Solomon HC. Neurosyphilis. New York: OxfordUniversity Press; 1946.29 Kakumani P, Hajj-Ali RA. A forgotten cause of CNS <strong>vasculitis</strong>. J Rheumatol(in press).30 Dawson TM, Starkebaum G. Isolated central <strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong> <strong>vasculitis</strong>associated with hepatitis C infection. J Rheumatol 1999; 26:2273–2276.31 Cacoub P, Sbai A, Hausfater P, et al. <strong>Central</strong> <strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong> involvement inhepatitis C virus infection. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 1998; 22:631–633.32 Oschmann P, Dorndorf W, Hornig C, et al. Stages and syndromes ofneuroborreliosis. J Neurol 1998; 245:262–272.33 Marra CM. Neurologic complications of Bartonella henselae infection. CurrOpin Neurol 1995; 8:164–169.34 Bahemuka M, Murungi JH. Tuberculosis of the <strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong>: a clinical,radiological and pathological study of 39 consecutive cases in Riyadh, SaudiArabia. J Neurol Sci 1989; 90:67–76.35 Barinagarrementeria F, Cantu C. Frequency of cerebral arteritis in subarachnoidcysticercosis: an angiographic study. Stroke 1998; 29:123–125.36 Nishino H, Rubino FA, DeRemee RA, et al. Neurological involvement inWegener’s granulomatosis: an analysis of 324 consecutive patients at theMayo Clinic. Ann Neurol 1993; 33:4–9.37 Moore PM, Calabrese LH. Neurologic manifestations of <strong>system</strong>ic vasculitides.Semin Neurol 1994; 14:300–306.38 Fauci AS, Haynes BF, Katz P, Wolff SM. Wegener’s granulomatosis:prospective clinical and therapeutic experience with 85 patients for 21 years.Ann Inter Med 1983; 98:76–85.39 Akman-Demir G, Serdaroglu P, Tasci B. Clinical patterns of neurologicalinvolvement in Behcet’s disease: evaluation of 200 patients. The Neuro-Behcet Study Group. Brain 1999; 122 (Pt 11):2171–2182.40 Al-Araji A, Sharquie K, Al-Rawi Z. Prevalence and patterns of neurologicalinvolvement in Behcet’s disease: a prospective study from Iraq. J NeurolNeurosurg Psychiatry 2003; 74:608–613.41 Brey RL. Neuropsychiatric lupus: clinical and imaging aspects. Bull NYU Hosp Joint Dis 2007; 65:194–199.This article reviews the current literature on clinical and imaging aspects ofneuropsychiatric lupus.42 Ellis SG, Verity MA. <strong>Central</strong> <strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong> involvement in <strong>system</strong>ic lupuserythematosus: a review of neuropathologic findings in 57 cases, 1955–1977. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1979; 8:212–221.43 Hanly JG, Walsh NM, Sangalang V. Brain pathology in <strong>system</strong>ic lupuserythematosus. J Rheumatol 1992; 19:732–741.44 Delalande S, de Seze J, Fauchais AL, et al. Neurologic manifestations in primarySjogren syndrome: a study of 82 patients. Medicine 2004; 83:280–291.45 Ando Y, Kai S, Uyama E, et al. Involvement of the central <strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong> inrheumatoid arthritis: its clinical manifestations and analysis by magneticresonance imaging. Inter Med 1995; 34:188–191.46 Vollertsen RS, Conn DL. Vasculitis associated with rheumatoid arthritis.Rheum Dis Clin North Am 1990; 16:445–461.47 Brey RL, Gharavi AE, Lockshin MD. Neurologic complications of antiphospholipidantibodies. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 1993; 19:833–850.48Muscal E, Brey RL. Neurologic manifestations of the antiphospholipid syndrome:integrating molecular and clinical lessons. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2008;10:67–73.An up-to-date review of neurologic manifestations of the APS and discussion of thetherapeutic modalities.49 Meroni PL, Tincani A, Sepp N, et al. Endothelium and the brain in CNS lupus.Lupus 2003; 12:919–928.50 Calabrese LH, Duna GF, Lie JT. Vasculitis in the central <strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong>.Arthritis rheum 1997; 40:1189–1201.51 Dimauro S, Hirano M. Pedaling from genotype to phenotype. Arch Neurol2006; 63:1679–1680.52 Richards A, van den Maagdenberg AM, Jen JC, et al. C-terminal truncations in human 3 0 –5 0 DNA exonuclease TREX1 cause autosomal dominant retinalvasculopathy with cerebral leukodystrophy. Nat Genet 2007; 39:1068–1070.Original mutation description of retinal vasculopathy with cerebral leukodystrophysyndrome.53 Stone JH, Pomper MG, Roubenoff R, et al. Sensitivities of noninvasive testsfor central <strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong> <strong>vasculitis</strong>: a comparison of lumbar puncture,computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging. J Rheumatol1994; 21:1277–1282.54 Pierot L, Chiras J, Debussche-Depriester C, et al. Intracerebral stenosingarteriopathies: contribution of three radiological techniques to the diagnosis.J Neuroradiol 1991; 18:32–48.55 Hurst RW, Grossman RI. Neuroradiology of central <strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong> <strong>vasculitis</strong>.Semin Neurol 1994; 14:320–340.56 Greenan TJ, Grossman RI, Goldberg HI. Cerebral <strong>vasculitis</strong>: MR imaging andangiographic correlation. Radiology 1992; 182:65–72.57 Doss-Esper CE, Singhal AB, Smith MS, Henderson GV. Reversible posteriorleukoencephalopathy, cerebral vasoconstriction, and strokes after intravenousimmune globulin therapy in guillain-barre syndrome. J Neuroimag 2005;15:188–192.58 Kadkhodayan Y, Alreshaid A, Moran CJ, et al. Primary angiitis of the central<strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong> at conventional angiography. Radiology 2004; 233:878–882.59 Duna GF, Calabrese LH. Limitations of invasive modalities in the diagnosis ofprimary angiitis of the central <strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong>. J Rheumatol 1995; 22:662–667.60 Calabrese LH. Clinical management issues in <strong>vasculitis</strong>. Angiographicallydefined angiitis of the central <strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong>: diagnostic and therapeuticdilemmas. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2003; 21 (6 Suppl 32):S127–S130.Copyright © Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

18 Vasculitis syndromes61 Parisi JE, Moore PM. The role of biopsy in <strong>vasculitis</strong> of the central <strong>nervous</strong><strong>system</strong>. Semin Neurol 1994; 14:341–348.62 Cupps TR, Moore PM, Fauci AS. Isolated angiitis of the central <strong>nervous</strong><strong>system</strong>: prospective diagnostic and therapeutic experience. Am J Med 1983;74:97–105.63 Molloy ES, Langford CA. Advances in the treatment of small vessel <strong>vasculitis</strong>.Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2006; 32:157–172.64 Chen D, Nishizawa S, Yokota N, et al. High-dose methylprednisolone preventsvasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage through inhibition of proteinkinase C activation. Neurol Res 2002; 24:215–222.65 Turesson C, Matteson EL. Management of extra-articular disease manifestationsin rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2004; 16:206–211.66 Unger L, Kayser M, Nusslein HG. Successful treatment of severe rheumatoid<strong>vasculitis</strong> by infliximab. Ann Rheum Dis 2003; 62:587–588.67Tokunaga M, Saito K, Kawabata D, et al. Efficacy of rituximab (anti-CD20) forrefractory <strong>system</strong>ic lupus erythematosus involving the central <strong>nervous</strong> <strong>system</strong>.Ann Rheum Dis 2007; 66:470–475.This report describes the clinical and laboratory tests of 10 patients with NPSLEbefore and after rituximab treatment.Copyright © Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.