Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology - Employees Csbsju

Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology - Employees Csbsju

Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology - Employees Csbsju

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Cross</strong>-<strong>Cultural</strong> <strong>Psychology</strong>http://jcc.sagepub.com<strong>Cultural</strong> and Evolutionary Components <strong>of</strong> Marital Satisfaction: A MultidimensionalAssessment <strong>of</strong> Measurement InvarianceTodd Lucas, Michele R. Parkhill, Craig A. Wendorf, E. Olcay Imamoglu, Carol C. Weisfeld, GlennE. Weisfeld and Jiliang Shen<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Cross</strong>-<strong>Cultural</strong> <strong>Psychology</strong> 2008; 39; 109DOI: 10.1177/0022022107311969The online version <strong>of</strong> this article can be found at:http://jcc.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/39/1/109Published by:http://www.sagepublications.comOn behalf <strong>of</strong>:International Association for <strong>Cross</strong>-<strong>Cultural</strong> <strong>Psychology</strong>Additional services and information for <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Cross</strong>-<strong>Cultural</strong> <strong>Psychology</strong> can be found at:Email Alerts: http://jcc.sagepub.com/cgi/alertsSubscriptions: http://jcc.sagepub.com/subscriptionsReprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.navPermissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.navCitations (this article cites 38 articles hosted on theSAGE <strong>Journal</strong>s Online and HighWire Press platforms):http://jcc.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/39/1/109Downloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at College <strong>of</strong> St. Benedict/St. John's University on April 10, 2008© 2008 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

CULTURAL AND EVOLUTIONARY COMPONENTSOF MARITAL SATISFACTIONA Multidimensional Assessment <strong>of</strong> Measurement InvarianceTODD LUCASWayne State UniversityMICHELE R. PARKHILLUniversity <strong>of</strong> WashingtonCRAIG A. WENDORFUniversity <strong>of</strong> Wisconsin–Stevens PointE. OLCAY I ⋅ MAMOĞLUMiddle East Technical University, Ankara, TurkeyCAROL C. WEISFELDUniversity <strong>of</strong> Detroit MercyGLENN E. WEISFELDWayne State UniversityJILIANG SHENBeijing Normal UniversityCouples assess their satisfaction with one another according to numerous culturally determined criteria.However, evolutionary perspectives on marriage emphasize that husbands and wives are also concerned withtheir adaptive fitness, and this suggests that some aspects <strong>of</strong> marital satisfaction may be cross-culturally homogenous.We examined whether marital satisfaction reflects both ‘culturally unique’ and ‘adaptively universal’ concerns<strong>of</strong> husbands and wives. Approximately 2000 couples from Britain, Turkey, China and the United Statescompleted a multidimensional measure <strong>of</strong> marital satisfaction that we assessed for measurement invariance.Measures <strong>of</strong> romantic love and spousal support functioned similarly for couples within all four cultures, indicatingthe possibility <strong>of</strong> a ubiquitous pair-bonding component <strong>of</strong> marital satisfaction. However, invariant measurementstructure was less robust across these samples, suggesting a culturally derived component <strong>of</strong> maritalsatisfaction. In general, results suggest that invariance analyses may be used to elucidate cultural and evolutionaryperspectives on marriage.Keywords:marriage; marital satisfactionl; invariance; love; Turkey; China; United Kingdom; United StatesInterpersonal relationships are heavily guided by norms, customs, and expectations thatare derived from culture (for reviews, see Berscheid, 1995; Fiske, Kitayama, Markus, &Nisbett, 1998). In particular, satisfaction with one’s spouse may largely depend on thedegree to which a marriage fulfills culturally determined expectations and obligations. OnAUTHORS’ NOTE: Portions <strong>of</strong> this article were prepared while the first author was a postdoctoral researcher at the Center forBehavioral and Decision Sciences in Medicine (Ann Arbor Veterans Affairs Hospital and University <strong>of</strong> Michigan). Portions <strong>of</strong>this research were presented at the 2003 annual meeting <strong>of</strong> the Human Behavior and Evolution Society, in Lincoln, Nebraska.We are grateful to Robin J. H. Russell and Pamela A. Wells for their contributions to this research. In addition, we acknowledgethe helpful comments <strong>of</strong> Cindy Gallois and two anonymous reviewers on prior versions <strong>of</strong> this article. Correspondence concerningthis article may be addressed to Todd Lucas, Division <strong>of</strong> Occupational and Environmental Health, Department <strong>of</strong> FamilyMedicine and Public Health Sciences, Wayne State University, 3800 Woodward Avenue, Suite 808; Detroit, MI 48201. E-mail:tlucas@med.wayne.edu.JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL PSYCHOLOGY, Vol. 39 No. 1, January 2008 109-123DOI: 10.1177/0022022107311969© 2008 Sage Publications109Downloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at College <strong>of</strong> St. Benedict/St. John's University on April 10, 2008© 2008 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

110 JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL PSYCHOLOGYthe other hand, evolutionary research and theory has emphasized that besides satisfyingculture-specific functions, marriage must also enhance the basic adaptive objectives <strong>of</strong>both husbands and wives. Specifically, marriage should facilitate not only procreation butalso appropriate caregiving behaviors for <strong>of</strong>fspring, and marital satisfaction may be importantto the extent that it enables this.The juxtaposition <strong>of</strong> cultural and evolutionary perspectives poses an interesting question formarital satisfaction research—namely, in what ways can satisfying marriages be both culturallyunique and universally adaptive? In the present study, we examined the measurement invariance<strong>of</strong> two indices <strong>of</strong> marital satisfaction (romantic love and communication/support) in couplesfrom the United States, Britain, Turkey, and China. To the extent that evolutionary andcultural perspectives respectively emphasize some alternative themes <strong>of</strong> marriage, our purposewas to determine whether two specific criteria that couples might use to define a satisfying marriageshould be considered inherently universal or culturally unique.MARITAL SATISFACTION AND CULTUREMarriages are generally more successful when spouses establish a sense <strong>of</strong> satisfaction withone another. However, researchers tend to diverge in their view <strong>of</strong> how satisfaction with one’sspouse is attained. Some <strong>of</strong> the most important and interesting distinctions are posited by culturaland evolutionary perspectives on marriage. From a cultural vantage point, marital satisfactionmay be enhanced to the extent that a marriage fulfills culturally determined expectationsand obligations <strong>of</strong> husbands and wives. In particular, the criteria for a satisfying marriage maybe highly varied and may depend on a unique set <strong>of</strong> culturally enforced norms, values, andobligations. For example, a traditional Chinese marriage may be satisfying to the extent that itfulfills familial duties that include the production <strong>of</strong> a male heir for the continuance <strong>of</strong> a familyline, the acquisition <strong>of</strong> a daughter-in-law who will provide support for the husband’s parents,and the begetting <strong>of</strong> sons who will provide for the security <strong>of</strong> the couple in their old age (Wang,1994). In addition, traditional Chinese marriages <strong>of</strong>ten represent the formation <strong>of</strong> an alliance <strong>of</strong>two extended families, whose interests supplant those <strong>of</strong> the to-be-married couple (Dion &Dion, 1993). On the other hand, Western cultures generally view marriage as serving fewerinstrumental and more personal functions and are thus thought to be satisfying to the extent thatthey fulfill happiness or hedonistic goals <strong>of</strong> husbands and wives (e.g., Lalonde, Hynie, Pannu,& Tatla, 2004). In addition, although social obligations are a defining feature <strong>of</strong> marriage inmany Eastern cultures, such influences may be viewed as obstacles to personal happiness inWestern cultures (Fiske et al., 1998).WITHIN-CULTURE HETEROGENEITY AND MARITAL SATISFACTION<strong>Cross</strong>-national differences are one defining feature <strong>of</strong> the cultural perspective. However, anequally important facet concerns the influence <strong>of</strong> economic and sociopolitical contexts withina culture (e.g., Zavalloni, 1975). In China, for example, the New Marriage Law <strong>of</strong> 1950 formallyabolished the traditional arranged marriage system and put in its place a system <strong>of</strong> freechoice and equal rights for both husbands and wives. China has also been informally influencedby Western thought that has further altered attitudes about marriage (Higgins, Zheng,Liu, & Hui Sun, 2002). However, a majority <strong>of</strong> the Chinese population live in rural areas,where formal and informal influences are not as powerful. Accordingly, covertly evolvedforms <strong>of</strong> traditional marriages can still occur in China (Wang, 1994). Thus, there is alsoDownloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at College <strong>of</strong> St. Benedict/St. John's University on April 10, 2008© 2008 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Lucas et al. / MARITAL SATISFACTION INVARIANCE 111within-culture heterogeneity <strong>of</strong> Chinese marriage in that it comprises both modern andmore traditional arrangements. Similar heterogeneity has also been observed in Turkey(I ⋅ mamoğlu & Yasak, 1997) and undoubtedly exists in many other nations. Generally, then,sociopolitical contexts may create varied criteria for marital satisfaction not only betweencultures but also within them.In addition to the heterogeneity created by sociopolitical variation, differences betweenhusbands and wives from the same culture may also contribute to variability in marital satisfactioncriteria. In this vein, researchers have hypothesized that men and women hold differentinstrumental and interpersonal views not only <strong>of</strong> marriage (e.g., Bernard, 1972) butalso <strong>of</strong> romantic relationships (e.g., Sprecher & Toro-Morn, 2002). One <strong>of</strong>ten overlookedpossibility is that spousal discrepancies in marital satisfaction may also depend on culture.For example, although British husbands and wives may think similarly about romanticlove but differently about spousal support, Chinese couples may agree on aspects <strong>of</strong>spousal support but differ in their views <strong>of</strong> romantic love.MARITAL SATISFACTION AND EVOLUTIONBolstered by recognition <strong>of</strong> both between- and within-culture differences, a generalconsensus is that cultural perspectives on marriage <strong>of</strong>ten emphasize heterogeneous qualities<strong>of</strong> marital satisfaction criteria. A somewhat contrasting viewpoint is <strong>of</strong>fered by an evolutionaryperspective on marriage, in which emphasis is <strong>of</strong>ten given to more universalcriteria. Although evolutionary mechanisms may produce cultural heterogeneity, evolutionaryresearch has tended to articulate a more ubiquitous and primal view not only onmating and marital preferences (e.g., Buss et al., 1990) but also on marital satisfaction(Shackelford & Buss, 1997). In this vein, evolutionary research has revealed that manypatterns in mate selection and marital stability are cross-culturally stable.From an evolutionary perspective, mating behavior—including mate selection, maritalsatisfaction, and divorce—is favored to the extent that it promotes individual reproductivesuccess. Both sexes tend to seek mature, opposite-sex members <strong>of</strong> their species who are notclose kin, which makes adaptive sense. However, men and women also exhibit somewhat differentideal criteria in mate selection. For example, cross-cultural surveys suggest that mengenerally prefer to marry younger, more attractive women who are high in reproductivepotential, whereas women prefer to marry older and wealthier men, who generally excel inproviding material resources and social status for the family (Buss, 1989). Other universalfeatures <strong>of</strong> mating behavior can also be explained in adaptive terms. For example, marital stabilityaround the world is associated with fecundity: the more children, the less chance <strong>of</strong>divorce (Goode, 1993). In addition, divorce in almost every culture is predicted by infertilityand infidelity, both <strong>of</strong> which may hinder individual fitness (Betzig, 1989).Marriage itself may also be interpreted in comparative terms as pair bonding—anevolved characteristic <strong>of</strong> species with highly dependent young that is thought to facilitateparental caregiving (Ember & Ember, 1979; Kleiman, 1977). Humans qualify as belongingto those species with highly dependent young. Therefore, from an evolutionary standpoint,it is not surprising that pair bonding, or marriage, is found in virtually every humanculture and is the generally preferred arrangement for raising children. Evidence aboundsthat children generally develop best if raised by both biological parents (e.g., Amato, 1993;Daly & Wilson, 1988), and marital satisfaction and stability are generally lower withstepchildren than with biological children (Rogers & White, 1998; Teachman & Heckert,Downloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at College <strong>of</strong> St. Benedict/St. John's University on April 10, 2008© 2008 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

112 JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL PSYCHOLOGY1985). Thus, evolutionists suggest that marriage is more than simply a cultural institution;it has an evolved basis. Because <strong>of</strong> its ubiquity, it may have generally been the most effectivearrangement in our species’ past for raising <strong>of</strong>fspring and passing on the parents’genes. Of course, this is not to say that heterosexual marriage is the only arrangement forsuccessfully raising children in contemporary societies.Evidence for an adaptively evolved propensity to marry may also include the universalemotional tendency to fall in love (e.g., Buss, 1988; Jankowiak & Fischer, 1992). Thisemotion usually includes sexual attraction as well as amorousness (Money & Ehrhardt,1972). Although some have suggested that the importance <strong>of</strong> romantic love in marriage isculturally varied (for review, see Landis & O’Shea, 2000), evidence for an evolved basisto this social emotion includes its hormonal supports, especially the effect <strong>of</strong> oxytocin onsocial bonding in humans and other mammals (Insel, 1997). Recently, a hormonal linkbetween pair bonding and paternal care has also been reported: Husbands <strong>of</strong> expectantwomen undergo a rise in prolactin, which increases paternal inclinations after the birth(Story, Walsh, Quinton, & Wynne-Edwards, 2000). In sum, although cultural perspectiveshave emphasized unique criteria for marital satisfaction, evolutionary research has suggestedthat marital arrangements serve adaptive fitness interests and that these shouldrelate to some aspects <strong>of</strong> marital satisfaction in a cross-culturally transcendent manner.THE PRESENT RESEARCHAlthough they differ in their emphasis on some important tenets <strong>of</strong> marital satisfaction,cultural and evolutionary outlooks are not mutually exclusive <strong>of</strong> one another. Undoubtedly,evolutionary mechanisms are likely to produce some unique cultural transmissions, andmany cultural norms and expectations serve some adaptive function. Furthermore, it wouldbe dubious to suggest that cultural and evolutionary perspectives respectively emphasizeonly heterogeneous and homogenous qualities <strong>of</strong> marital satisfaction or that they are otherwiseincompatible with one another. Nevertheless, to the extent that cultural and evolutionaryperspectives <strong>of</strong>ten lead to theory and research on unique versus universalcharacteristics <strong>of</strong> marriage, there are at least some alternative points <strong>of</strong> emphasis. The juxtaposition<strong>of</strong> culture and evolution thus frames an important question for marriageresearch—namely, in what ways are marital satisfaction criteria universally similar andculturally unique? In addition, do similarities and differences in the composition <strong>of</strong> maritalsatisfaction across cultures map onto themes that seem to be emphasized by evolutionaryand cultural viewpoints?One way <strong>of</strong> formally exploring evolutionary and cultural perspectives on marital satisfactionis to undertake a cross-cultural examination <strong>of</strong> the measurement invariance <strong>of</strong> maritalsatisfaction indices. Invariance testing is a form <strong>of</strong> covariance structure analysisdesigned to assess whether measures, such as those composing marital satisfaction, aredefined similarly across different groups (e.g., Byrne & Campbell, 1999; Cheung &Rensvold, 1999; Vandenberg & Lance, 2000). Invariance testing is increasingly commonlyused in test construction and scale development endeavors to assess the measurementequivalency <strong>of</strong> newly established instruments (e.g., Lucas, Alexander, Firestone, &LeBreton, 2007; Lucas, Michalopoulou, Falzerano, Menon, & Cunningham, in press).However, invariance testing has also gained prominence in cross-cultural research by providinga method for analyzing similarities and differences in the composition <strong>of</strong> measuresthat are compared cross-culturally. Thus, one ready benefit <strong>of</strong> invariance testing is that itmay be used to assess a desirable statistical property <strong>of</strong> measures prior to their use inDownloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at College <strong>of</strong> St. Benedict/St. John's University on April 10, 2008© 2008 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Lucas et al. / MARITAL SATISFACTION INVARIANCE 113research (i.e., to ensure that cross-cultural comparisons are aptly based on unequivocallyfunctioning measures). However, a second benefit <strong>of</strong> invariance testing is that it may beused on occasion to answer questions <strong>of</strong> theoretical substance that are <strong>of</strong> interest toresearchers, as when noninvariance itself is treated as a form <strong>of</strong> empirical evidence (e.g.,Cheung & Rensvold, 1999). In this latter respect, invariance testing may afford opportunitiesto examine theoretical viewpoints, such as those posited by evolutionary and culturalperspectives on marital satisfaction.In the present research, we used invariance testing to examine the equivalency <strong>of</strong> marital satisfaction.Specifically, we recruited couples from the United States, Britain, Turkey, and Chinato assess the extent to which satisfying marriages were cross-culturally similar versus unique.In accordance with multidimensional conceptualizations, we examined two possible domains<strong>of</strong> marital satisfaction, including romantic love, and also communication and support. In addition,because we recruited intact couples, our data allowed us to examine not only betweencultureinvariance (i.e., the extent to which satisfaction measures for husbands from all four <strong>of</strong>our cultures were invariant) but also within-culture invariance (i.e., the extent to which measuresfor husbands and wives from the same culture were invariant with one another). Thus, ourstudy examined two independent facets <strong>of</strong> marital satisfaction invariance—between-culturesimilarities <strong>of</strong> same-gendered spouses (i.e., cultural invariance) and within-culture similarities<strong>of</strong> husbands and wives (i.e., spousal invariance).In accordance with an evolutionary perspective on marriage, we interpreted culturallyinvariant aspects <strong>of</strong> marital satisfaction as supportive <strong>of</strong> some adaptively evolved functions<strong>of</strong> marriage (i.e., as facilitating procreation and pair bonding). Specifically, and in view <strong>of</strong>literature that regards romantic love as an attachment process (Hazan & Shaver, 1987) andaffective bonds as universal (van Ijzendoorn & Sagi, 1999), we expected our measures <strong>of</strong>spousal love and support to be cross-culturally invariant (Dion & Dion, 1993; Hazan &Zeifman, 1994). In addition, because <strong>of</strong> their shared cultural heritage, we expected thatinvariance would be stronger between husbands and wives from the same culture than forsame-sex spouses from different cultures.PARTICIPANTSMETHODWe recruited more than 2,000 married couples from the United States, Britain, China,and Turkey (see Table 1). All couples were recruited from predominantly urban areas ineach <strong>of</strong> their respective countries. As a method <strong>of</strong> convenience sampling, this strategy wasappropriate to the extent that urban areas encompass a large proportion <strong>of</strong> married individualsliving within each <strong>of</strong> our four selected nations. However, our samples were nonrandomand therefore do not represent the entirety <strong>of</strong> marriage within each culture or theentirety <strong>of</strong> culture within each nation. A total <strong>of</strong> 322 U.S. and 350 Turkish couples wererecruited using modified snowball sampling (Bailey, 1987). We recruited 1,031 Britishcouples through various techniques that included placing an advertisement in a women’smagazine, hiring a market research company, and enlisting college students to carry outconvenience sampling. Finally, we recruited 232 Chinese couples by giving their childrena questionnaire at school to deliver home to their parents. In all four samples, husbandswere slightly older than their wives, and couples had been married for an average <strong>of</strong> atleast 11 years. However, there were some notable differences across our samples as well.Downloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at College <strong>of</strong> St. Benedict/St. John's University on April 10, 2008© 2008 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

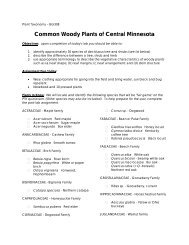

114 JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL PSYCHOLOGYTABLE 1Sample DemographicsUnited States Britain China TurkeySample Size (N = 322) (N = 1,031) (N = 232) (N = 350)Husband age in years (SD) 42.35 (10.81) a 38.47 (12.44) b 39.84 (7.60) b 38.33 (10.09) bWife age in years (SD) 39.94 (10.31) a 36.14 (12.01) b 38.05 (6.97) c 34.19 (9.34) dLength <strong>of</strong> marriage in years (SD) 15.32 (11.26) a 13.17 (10.43) b,d 13.94 (7.76) a,b,c 11.76 (9.46) dNOTE: Sample size denotes number <strong>of</strong> couples. Values with noncommon superscripts indicate significant pairwisedifferences (Tukey Honestly Significant Difference, p < .05).For example, the mean age <strong>of</strong> wives was different for all samples, with Turkish wivesbeing the youngest and American wives being the oldest.MATERIALSAll participants completed the Marriage and Relationships Questionnaire (MARQ) developedby Russell and Wells (1986). The original version <strong>of</strong> the MARQ comprises 235 multiplechoice and true/false items and was developed using British couples in the late 1980s (seeRussell & Wells, 1993). The survey was originally designed to give a broad view <strong>of</strong> respondents’feelings both about themselves and about their relationship with their spouse. Parallelversions <strong>of</strong> the MARQ exist for administration to both husbands and wives. The measure isdecidedly subjective in its attempt to capture husband and wife perceptions <strong>of</strong> themselvesand each other. However, the MARQ is objective in the sense that couples may be formallycompared to one another, and to other couples, on numerous aspects <strong>of</strong> marital satisfaction.Although it is less well known, the MARQ is similar to many other measures <strong>of</strong> marital satisfactionto the extent that it has been used to benchmark associations between spousal perceptionsand relationship satisfaction (e.g., Lucas et al., 2004). However, the MARQ isdistinguished by the extent to which it defines marital satisfaction multidimensionally.Specifically, more than a dozen scales assessing various aspects <strong>of</strong> marital relationships areformally and informally derived from the MARQ. The MARQ was advantageous in the presentstudy because <strong>of</strong> this highly multidimensional operationalization.We selected two subscales <strong>of</strong> the MARQ for the present study (see the appendix). Thenine-item Love scale was designed to measure emotional or romantic attachment to one’sspouse (e.g., “Do you find your spouse attractive?”). The nine-item Partnership scaleassessed perceived communication and support <strong>of</strong> one’s spouse (e.g., “Is there enough giveand take in your relationship?”). All items were answered using a 5-point Likert-type scalewith individually appropriate labels. Cronbach’s alpha values are reported Table 2 for husbandsand wives in each <strong>of</strong> our four cultures.STATISTICAL ANALYSESAlthough more stringent criteria may be used (i.e., Little, 2000), measures are most<strong>of</strong>ten considered invariant across groups when they demonstrate structural equivalency.Configural equivalency, a less restrictive form <strong>of</strong> invariance, is defined as a uniform factorstructure across groups and comprises the first requirement <strong>of</strong> structural equivalency(Cheung & Rensvold, 1999; Vandenberg & Lance, 2000). Configural invariance existswhen parallel items load significantly onto the same constructs across all assessed groups.Downloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at College <strong>of</strong> St. Benedict/St. John's University on April 10, 2008© 2008 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Lucas et al. / MARITAL SATISFACTION INVARIANCE 115TABLE 2MARQ Scale Internal ConsistenciesScale Items Group AlphaLove 9 American husbands .91American wives .91British husbands .89British wives .91Chinese husbands .87Chinese wives .86Turkish husbands .87Turkish wives .89Partnership 9 American husbands .90American wives .91British husbands .87British wives .90Chinese husbands .88Chinese wives .88Turkish husbands .86Turkish wives .86NOTE: MARQ = Marriage and Relationships Questionnaire.Usually, configural equivalency determines a baseline model <strong>of</strong> invariance by providing aplatform for next assessing metric invariance, the second requirement <strong>of</strong> structural equivalency(Vandenberg & Lance, 2000). Metric invariance is generally equated with strongfactorial invariance and is more restrictive than configural invariance in requiring equivalentitem loadings (i.e., factor scores for a given item are equivalent across groups).Historically, researchers have suggested that the means <strong>of</strong> the latent variables can becompared across groups once metric invariance has been established (Cheung & Rensvold,1999). However, more recent recommendations (e.g., Byrne, 2001) have suggested thatintercept invariance may also be required for structural equivalency. We thereforeemployed a third requirement <strong>of</strong> structural equivalency by assessing not only configuraland metric invariance but also the equivalency <strong>of</strong> item intercepts. In cases where all threerequirements <strong>of</strong> structural equivalency were met, we examined one final form <strong>of</strong> invarianceby examining the equivalency <strong>of</strong> latent variable means. Thus, although our primaryanalyses related to the equivalency <strong>of</strong> structure in our measures <strong>of</strong> marital satisfaction, wealso examined equivalency <strong>of</strong> level in cases where structure was invariant.We examined the invariance <strong>of</strong> each <strong>of</strong> our four marital satisfaction measures usingcovariance structure analyses. All analyses were performed using LISREL 8.30 (Jöreskog& Sörbom, 1999) and maximum likelihood estimation. In all instances, scale restrictionwas imposed by constraining the latent variable variances to one. Because <strong>of</strong> our largesample sizes, we expected that the normal weighted theory chi-square statistic would besignificant (Marsh, Balla, & McDonald, 1988). We therefore examined several additionalfit indices, including the nonnormed fit index (NNFI; Bentler & Bonett, 1980), the comparativefit index (CFI; Bentler, 1990; Satorra & Bentler, 1994), and the root mean squareerror <strong>of</strong> approximation (RMSEA; Browne & Cudeck, 1993). Values <strong>of</strong> .90 or higher arethought to indicate good overall fit for the NNFI and the CFI, whereas values up to .08 aregenerally considered acceptable for the RMSEA.Invariance testing requires an assessment <strong>of</strong> changes in overall model fit that occurwhen restricted models impose additional equivalency constraints on items. Generally,Downloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at College <strong>of</strong> St. Benedict/St. John's University on April 10, 2008© 2008 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

116 JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL PSYCHOLOGYa chi-square difference test is used, and invariance is established when the imposed equivalencies<strong>of</strong> metric, intercept, and slope invariance do not significantly reduce the fit <strong>of</strong> aprevious model (Rensvold & Cheung, 1998; Steiger, Shapiro, & Browne, 1985). However,because chi-square tests are susceptible to sample size and degrees <strong>of</strong> freedom, we concludedinvariance when changes in the CFI <strong>of</strong> .01 or less were observed in a more stringentlyconstrained model (Cheung & Rensvold, 1999), whereas additional fit indicescontinued to suggest a generally good overall fit (Little, 1997).We assessed equivalency using two sets <strong>of</strong> covariance structure equality tests. In the firstset, we assessed invariance between husbands and wives within each <strong>of</strong> the four cultures (i.e.,spousal invariance). Similar to time-series covariance analyses, we allowed the residual terms<strong>of</strong> husbands and wives to correlate for parallel items. In the second set, we assessed invarianceacross same-gendered spouses from all four cultures (i.e., cultural invariance). For bothspousal and cultural invariance, we concluded configural invariance if an initially unconstrainedmodel fit well. We then ran additional models in which item loadings, intercepts, andmeans were incrementally constrained to be equal across groups (e.g., corresponding itemloadings equal for wives across all four cultures). If overall fit was retained in a more constrainedmodel, we concluded that invariance could be ascribed to the prior model.RESULTSOur primary hypothesis was that invariance would be established for both love and partnershipmeasures. In addition, because <strong>of</strong> their shared culture, we expected strongerspousal invariance (i.e., within culture) than cultural invariance (i.e., husbands from allfour cultures) for both <strong>of</strong> these aspects <strong>of</strong> marital satisfaction. The results <strong>of</strong> both sets <strong>of</strong>analyses are presented in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. For each measure <strong>of</strong> marital satisfaction,the most stringent level <strong>of</strong> invariance that was obtained is highlighted. In allinstances, tests <strong>of</strong> invariance concluded once a constrained model demonstrated insufficientfit with a prior and less constrained model.Spousal invariance was generally attained in couples from all four cultures. Foremost,structural invariance was established for scales measuring both love and partnership. In addition,an equivalent level for both love and partnership was obtained within culture, indicatingthat husbands and wives were similar in the amount <strong>of</strong> both types <strong>of</strong> satisfaction that theydisplayed for one another. As expected, cultural invariance was generally more difficult toobtain than spousal invariance. At least some forms <strong>of</strong> structural invariance were obtained forlove and partnership when these measures were assessed cross-culturally. However, and inall instances, although metric invariance was obtained for both husbands and wives on thesemeasures, the additional constraint <strong>of</strong> intercept invariance significantly reduced model fit.DISCUSSIONOverall, Love and Partnership scales were invariant across couples from all four <strong>of</strong> ourcultures, thus supporting the possibility that they are an adaptively evolved component <strong>of</strong>marital satisfaction. However, cultural invariance <strong>of</strong> these measures was less robust, indicatingthat these aspects <strong>of</strong> marital satisfaction might also be defined uniquely by particularnorms, values, and expectations about marriage. Taken together, these results supportDownloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at College <strong>of</strong> St. Benedict/St. John's University on April 10, 2008© 2008 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Lucas et al. / MARITAL SATISFACTION INVARIANCE 117TABLE 3Spousal Invariance <strong>of</strong> Marital Satisfaction in Four CulturesScale and Model df χ 2 RMSEA NNFI CFI ∆df ∆χ 2 ∆CFIAmerican (N = 322)LoveConfigural 125 444.24*** .088 .90 .92 — — —Metric 134 454.21*** .085 .91 .92 9 9.81 .00Intercept 142 477.44*** .084 .91 .92 8 23.23** .00Mean 143 477.11*** .084 .91 .92 1 0.33 .00PartnershipConfigural 125 189.01*** .039 .97 .98 — — —Metric 134 195.70*** .037 .98 .98 9 6.69 .00Intercept 142 215.52*** .040 .97 .97 8 19.82* .01Mean 143 215.53*** .039 .97 .97 1 0.01 .01British (N = 1,031)LoveConfigural 125 740.88*** .069 .93 .94 — — —Metric 134 790.56*** .069 .93 .94 9 49.68*** .00Intercept 142 979.38*** .071 .92 .93 8 188.82*** .01Mean 143 1,011.97*** .077 .91 .93 1 32.59*** .00PartnershipConfigural 125 563.56*** .058 .94 .95 — — —Metric 134 629.33*** .060 .93 .94 9 65.77*** .01Intercept 142 815.85*** .068 .92 .93 8 186.52*** .01Mean 143 821.73*** .068 .92 .93 1 5.88* .00Chinese (N = 232)LoveConfigural 125 246.55*** .065 .91 .92 — — —Metric 134 253.59*** .062 .91 .92 9 7.04 .00Intercept 142 309.47*** .071 .90 .91 8 56.08*** .01Mean 143 314.52*** .072 .90 .91 1 5.05* .00PartnershipConfigural 125 213.38*** .055 .94 .95 — — —Metric 134 231.55*** .056 .94 .95 9 18.17* .00Intercept 142 253.56*** .058 .93 .94 8 22.01** .01Mean 143 256.72*** .059 .93 .94 1 3.16 .00Turkish (N = 350)LoveConfigural 125 293.07*** .062 .93 .94 — — —Metric 134 307.39*** .061 .93 .94 9 14.32 .00Intercept 142 340.42*** .063 .93 .93 8 33.03*** .01Mean 143 344.02*** .063 .93 .93 1 3.60 .00PartnershipConfigural 125 220.15*** .047 .95 .96 — — —Metric 134 247.61*** .049 .95 .95 9 27.46** .01Intercept 142 261.65*** .049 .95 .95 8 14.04 .00Mean 143 280.35*** .052 .94 .94 1 18.70*** .01NOTE: RMSEA = root mean square error <strong>of</strong> approximation; NNFI = nonnormed fit index; CFI = comparativefit index. Bold lines indicate highest level <strong>of</strong> invariance attained for each analysis.*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.a multidimensional view <strong>of</strong> marital satisfaction in suggesting that both evolutionarilyinvariant and culturally unique criteria may be reflected in marital satisfaction ratings <strong>of</strong>husbands and wives.Downloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at College <strong>of</strong> St. Benedict/St. John's University on April 10, 2008© 2008 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

118 JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL PSYCHOLOGYTABLE 4<strong>Cultural</strong> Invariance <strong>of</strong> Marital Satisfaction for Husbands and WivesScale and Model df χ 2 RMSEA NNFI CFI ∆df ∆χ 2 ∆CFIHusbands (N = 1,945)LoveConfigural 108 619.35*** .093 .93 .95 — — —Metric 135 706.80*** .088 .94 .94 27 87.45*** .01Intercept 159 1,240.37*** .120 .89 .88 24 533.57*** .06PartnershipConfigural 108 421.92*** .073 .95 .96 — — —Metric 135 560.72*** .076 .93 .95 27 138.82*** .01Intercept 159 1,044.95*** .110 .89 .88 24 484.23*** .07Wives (N = 1,945)LoveConfigural 108 666.86*** .097 .93 .95 — — —Metric 135 759.41*** .091 .93 .94 27 92.55*** .01Intercept 159 1,162.73*** .110 .90 .89 24 403.32*** .05PartnershipConfigural 108 513.06*** .082 .94 .96 — — —Metric 135 631.46*** .082 .93 .95 27 118.40*** .01Intercept 159 1,302.06*** .120 .88 .86 24 670.60*** .09NOTE: RMSEA = root mean square error <strong>of</strong> approximation; NNFI = nonnormed fit index; CFI = comparativefit index. Bold lines indicate highest level <strong>of</strong> invariance attained for each analysis.***p < .001.Although romantic love is sometimes seen as characteristic <strong>of</strong> marriage in Western cultures,evolutionary researchers have historically emphasized its ubiquitous role in marriage.For example, Jankowiak and Fischer (1992) have suggested that there exists auniversal amorous component to marriage. Others have noted that even within traditionalcultures in which there are arranged marriages, most couples eventually fall in love (forreviews, see Lucas et al., 2004; Weisfeld & Weisfeld, 2002). Although there are many plausibleinterpretations, one possibility is that romantic love may be an adaptively evolvedcomponent <strong>of</strong> marital satisfaction to the extent that it facilitates both procreation and caregiving.The results <strong>of</strong> this study lend support to this possibility in that spouses were similarto one another in romantic love across all four <strong>of</strong> our cultures.In addition to romantic love, there are numerous evolutionary arguments that supportubiquitous partnership arrangements in marriage. Most notably, communication and supportbetween husbands and wives may enhance caregiving. Couples who are unable tocoordinate complex support routines that are demanded by a child, or who are generallyunsupportive <strong>of</strong> one another, may perform less successfully as parents. Accordingly, selectionpressures should favor at least some universally adaptive forms <strong>of</strong> communicationbetween husbands and wives for the purpose <strong>of</strong> supporting children. Thus, in addition toromantic love, marriage may require at least some unequivocal partnership behaviors thatare generally reflected in couples’ sense <strong>of</strong> satisfaction with one another.Although evolutionary explanations <strong>of</strong> marital satisfaction are at least plausible according tospousal invariance, a lack <strong>of</strong> full cultural invariance in the present study also suggests that maritalsatisfaction criteria may be determined by culture. In this vein, theory and research supportthat husbands and wives from different cultures may define their satisfaction with one anotherin unique ways. For example, religion is thought to play an important role in spouses’ satisfactionwith one another in many cultures. In China, however, there is a tenuous connectionDownloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at College <strong>of</strong> St. Benedict/St. John's University on April 10, 2008© 2008 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Lucas et al. / MARITAL SATISFACTION INVARIANCE 119between religion and marriage, as religion has been discouraged politically for most <strong>of</strong> thepast century. Marital satisfaction may vary in other less formal ways as well. For example,Campos, Keltner, Beck, Gonzaga, and John (2007) recently suggested that teasing, a socialinteraction that benefits relational bonds at the expense <strong>of</strong> the self, may be viewed morepositively by Eastern than Western cultures. Thus, playful teasing within the context <strong>of</strong>marriage may be viewed differently by couples from different cultures. Perhaps mostimportantly, our results suggest that romantic love and partnership, which compose twoseemingly universal qualities <strong>of</strong> a satisfying marriage, may also reflect cultural criteria.LIMITATIONSThere are several methodological limitations <strong>of</strong> our research. Foremost, our results arelimited by the nature <strong>of</strong> our samples. Samples from all four cultures were nonrepresentativeand predominantly urban, and thus, they do not reflect the entirety <strong>of</strong> each culture. Inaddition, although they were selected to provide diversity in geography, economic development,religion, and political system, our samples do not reflect the entirety <strong>of</strong> cultureacross the globe. It is entirely possible that the invariance <strong>of</strong> marital satisfaction would presentitself differently not only across a broader range <strong>of</strong> cultures but also if more representativesamples were available from within each culture. In addition, our results arecharacterized by uneven sample sizes. Although our use <strong>of</strong> relative fit indices minimizesany potential influence, this characteristic nevertheless confounds the fit indices that weobtained for each test <strong>of</strong> invariance.A second set <strong>of</strong> limitations concerns the use <strong>of</strong> marital satisfaction indices that weredeveloped in a Western culture. Undoubtedly, our assessments <strong>of</strong> marital satisfaction wereoperationalized using at least some culturally specific perceptions and benchmarks, and thiscould differentially affect the fit <strong>of</strong> these measures in non-Western cultures. In addition, maritalsatisfaction may be defined beyond considering only romantic love and partnership.Thus, researchers might consider replicating our results using alternative and additional measures<strong>of</strong> marital satisfaction. Such an undertaking should additionally consider better knownand more commonly used marital satisfaction measures. However, as noted previously, webelieve that the use <strong>of</strong> the MARQ in the present study was advantageous at least to the extentthat it defines marital satisfaction in a highly multidimensional manner, and this affordedboth evolutionary and cultural considerations <strong>of</strong> spousal satisfaction.A final set <strong>of</strong> limitations concerns our interpretation <strong>of</strong> invariance results. Specifically,we interpreted invariance characteristics as strictly supportive <strong>of</strong> either evolutionary or culturallydefined criteria <strong>of</strong> marital satisfaction. However, these perspectives are not mutuallyexclusive. The existence <strong>of</strong> cross-culturally diverse marital values certainly does notpreclude the influence <strong>of</strong> evolutionary forces in this domain, nor does the homogeneity <strong>of</strong>satisfaction preclude the importance <strong>of</strong> culture. In addition, tests <strong>of</strong> invariance do not <strong>of</strong>ferunequivocal support for either cultural or evolutionary interpretations <strong>of</strong> marriage. Forexample, although spousal invariance <strong>of</strong> romantic love does not rule out the possibility <strong>of</strong>an evolutionary interpretation, there are many other equally viable explanations that alsoremain. Similarly, noninvariance could merely indicate cultural differences in ways <strong>of</strong>answering survey items, such as unique use <strong>of</strong> scale midpoints (e.g., Cheung & Rensvold,2000). Invariance testing is also limited in that it requires an imposed-epic approach todefining marital satisfaction, which may promote the potential for cross-cultural standardizationat the expense <strong>of</strong> measurement misspecification.Downloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at College <strong>of</strong> St. Benedict/St. John's University on April 10, 2008© 2008 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

120 JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL PSYCHOLOGYCONCLUSIONThe present study addressed the cross-cultural measurement invariance <strong>of</strong> two indices <strong>of</strong>marital satisfaction. Results generally supported the possibility <strong>of</strong> universal multidimensionalcriteria in marital satisfaction. However, results also suggested unique cultural definitions<strong>of</strong> marital satisfaction. We believe the current study provides an important step towardestablishing both universality and uniqueness in indices <strong>of</strong> marital satisfaction. In addition,we suggest the possibility that measures <strong>of</strong> marital satisfaction may reflect themes that areemphasized by cultural and evolutionary perspectives on marriage. Although there are limitations,future studies in this area may continue to apply invariance analyses to examinewhether they reflect the components <strong>of</strong> marital satisfaction proposed on the basis <strong>of</strong> culturaland evolutionary perspectives.APPENDIXScaleLovePartnershipItemDo you enjoy your spouse’s company?Are you happy?Do you find your spouse attractive?Do you enjoy doing things together?Do you enjoy cuddling your spouse?Do you respect your spouse?Are you proud <strong>of</strong> your spouse?Does your marriage have a romantic side?How much do you love your spouse?Do you find your spouse easy to get along with?If you are unhappy, can you discuss it with your spouse?Is your spouse kind to you?Does your spouse sympathize when you are under pressure?Does your spouse know what you really think and feel?Is there enough give and take in your marriage?Does your spouse understand you?Does your spouse support you in what you are trying to do?Does your spouse respect you?NOTE: All items answered using an appropriately labeled 5-point Likert-type scale.REFERENCESAmato, P. R. (1993). Children’s adjustment to divorce: Theories, hypotheses, and empirical support. <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong>Marriage and Family, 55, 23-38.Bailey, K. D. (1987). Methods <strong>of</strong> social research. New York: Free Press.Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indices in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 238-246.Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness <strong>of</strong> fit on the analysis <strong>of</strong> covariance structures.Psychological Bulletin, 88, 588-606.Bernard, J. (1972). The future <strong>of</strong> marriage. New York: World Books.Berscheid, E. (1995). Help wanted: A grand theorist <strong>of</strong> interpersonal relationships, sociologist or anthropologistpreferred. <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Social and Personal Relationships, 12, 529-533.Betzig, L. (1989). Causes <strong>of</strong> conjugal dissolution: A cross-cultural study. Current Anthropology, 30, 654-676.Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways <strong>of</strong> assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long(Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136-162). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.Downloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at College <strong>of</strong> St. Benedict/St. John's University on April 10, 2008© 2008 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Lucas et al. / MARITAL SATISFACTION INVARIANCE 121Buss, D. M. (1988). Love acts: The evolutionary biology <strong>of</strong> love. In R. J. Sternberg & M. L. Barnes (Eds.), Thepsychology <strong>of</strong> love (pp. 100-118). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.Buss, D. M. (1989). Sex differences in human mate preferences: Evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures.Behavioral & Brain Sciences, 12(1), 1-49.Buss, D. M., Abbott, M., Angleitner, A., Asherian, A., Biaggio, A., Blanco-Villasenor, A., et al. (1990).International preferences in selecting mates: A study <strong>of</strong> 37 cultures. <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Cross</strong>-<strong>Cultural</strong> <strong>Psychology</strong>,21(1), 5-47.Byrne, B. M. (2001). Structural equation modeling with AMOS, EQS, and LISREL: Comparative approaches totesting for the factorial validity <strong>of</strong> a measuring instrument. International <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Testing, 1, 55-86.Byrne, B. M., & Campbell, T. L. (1999). <strong>Cross</strong>-cultural comparisons and the presumption <strong>of</strong> equivalent measurementand theoretical structure: A look beneath the surface. <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Cross</strong>-<strong>Cultural</strong> <strong>Psychology</strong>, 30,555-574.Campos, B., Keltner, D., Beck, J., Gonzaga, G. C., & John, O. P. (2007). Culture and teasing: The relational benefits<strong>of</strong> reduced desire for positive differentiation. Personality and Social <strong>Psychology</strong> Bulletin, 33, 3-16.Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (1999). Testing factorial invariance across groups: A reconceptualization andproposed new method. <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Management, 25(1), 1-27.Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2000). Assessing extreme and acquiescence response sets in cross-culturalresearch using structural equation modeling. <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Cross</strong>-<strong>Cultural</strong> <strong>Psychology</strong>, 31, 187-212.Daly, M., & Wilson, M. (1988). Homicide. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.Dion, K. L., & Dion, K. K. (1993). Individualistic and collectivistic perspectives on gender and the cultural context<strong>of</strong> love and intimacy. <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Social Issues, 49, 53-69.Ember, M., & Ember, C. R. (1979). Male-female bonding: A cross-species study <strong>of</strong> mammals and birds.Behaviour Science Research, 14, 37-56.Fiske, A., Kitayama, S., Markus, H. R., & Nisbett, R. E. (1998). The cultural matrix <strong>of</strong> social psychology. InD. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook <strong>of</strong> social psychology (Vol. 2, 4th ed., pp. 915-981). New York: McGraw-Hill.Goode, W. J. (1993). World changes in divorce patterns. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Personalityand Social <strong>Psychology</strong>, 52, 511-524.Hazan, C., & Zeifman, D. (1994). Sex and the psychological tether. Advances in Personal Relationships, 5, 151-177.Higgins, L. T., Zheng, M., Liu, Y., & Hui Sun, C. (2002). Attitudes to marriage and sexual behaviors: A survey<strong>of</strong> gender and culture differences in China and United Kingdom. Sex Roles, 46(3/4), 75-89.I ⋅ mamoğlu, E. O., & Yasak, Y. (1997). Dimensions <strong>of</strong> marital relationships as perceived by Turkish husbands andwives. Genetic, Social and General <strong>Psychology</strong> Monographs, 123(2), 211-232.Insel, T. R. (1997). A neurobiological basis <strong>of</strong> social attachment. American <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Psychiatry, 154, 726-735.Jankowiak, W. R., & Fischer, E. F. (1992). A cross-cultural perspective on romantic love. Ethnology, 31, 149-155.Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (1999). LISREL, version 8.30. Chicago: Scientific S<strong>of</strong>tware International.Kleiman, D. G. (1977). Monogamy in mammals. Quarterly Review <strong>of</strong> Biology, 52, 39-69.Lalonde, R. N., Hynie, M., Pannu, M., & Tatla, S. (2004). The role <strong>of</strong> culture in interpersonal relationships: Dosecond generation South Asian Canadians want a traditional partner? <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Cross</strong>-<strong>Cultural</strong> <strong>Psychology</strong>,35, 503-524.Landis, D., & O’Shea, W. A. (2000). <strong>Cross</strong>-cultural aspects <strong>of</strong> passionate love: An individual differences analysis.<strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Cross</strong>-<strong>Cultural</strong> <strong>Psychology</strong>, 31, 752-777.Little, T. D. (1997). Mean and covariance structures (MACS) analyses <strong>of</strong> cross-cultural data: Practical and theoreticalissues. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 32(1), 53-76.Little, T. D. (2000). On the comparability <strong>of</strong> constructs in cross-cultural research: A critique <strong>of</strong> Cheung andRensvold. <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Cross</strong>-<strong>Cultural</strong> <strong>Psychology</strong>, 31(2), 213-219.Lucas, T., Alexander, S., Firestone, I. J., & LeBreton, J. M. (2007). Development and initial validation <strong>of</strong> a proceduraland distributive just world measure. Personality and Individual Differences, 43, 71-82.Lucas, T., Michalopoulou, G., Falzerano, P., Menon, S., & Cunningham, W. (in press). Healthcare provider culturalcompetency: Initial validation <strong>of</strong> a patient report measure. Health <strong>Psychology</strong>.Lucas, T., Wendorf, C. A., Imamoglu, E. O., Shen, J., Parkhill, M. R., Weisfeld, C. C., et al. (2004). Marital satisfactionin four cultures as a function <strong>of</strong> homogamy, male dominance and female attractiveness. Sexualities,Evolution and Gender, 6, 97-130.Marsh, H. M., Balla, J. R., & McDonald, R. P. (1988). Goodness-<strong>of</strong>-fit indexes in confirmatory factor analysis:The effect <strong>of</strong> sample size. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 391-410.Money, J., & Ehrhardt, A. A. (1972). Man & woman, boy & girl. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.Downloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at College <strong>of</strong> St. Benedict/St. John's University on April 10, 2008© 2008 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

122 JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL PSYCHOLOGYRensvold, R. B., & Cheung, G. W. (1998). Testing measurement models for factorial invariance: A systematicapproach. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 58(6), 1017-1034.Rogers, S. J., & White, L. K. (1998). Satisfaction with parenting: The role <strong>of</strong> marital happiness, family structure,and parents’ gender. <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> Marriage and Family, 60, 293-308.Russell, R. J. H., & Wells, P. A. (1986). Marriage questionnaire. Unpublished booklet.Russell, R. J. H., & Wells, P. A. (1993). Marriage and relationship questionnaire: MARQ handbook. Kent, UK:Hodder and Stoughton.Satorra, A., & Bentler, P. M. (1994). Corrections to test statistics and standard errors in covariance structureanalysis. In A. VonEye & C. C. Clogg (Eds.), Latent variable analysis: Applications for developmentalresearch (pp. 399-519). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.Shackelford, T. K., & Buss, D. M. (1997). Marital satisfaction in evolutionary psychological perspective. In R. J.Sternberg & M. Hojjatt (Eds.), Satisfaction in close relationships (pp. 7-25). New York: Guilford.Sprecher, S., & Toro-Morn, M. (2002). A study <strong>of</strong> men and women from different sides <strong>of</strong> Earth to determine ifmen are from Mars and women are from Venus in their beliefs about love and romantic relationships. SexRoles, 46(5/6), 131-147.Steiger, J. H., Shapiro, A., & Browne, M. W. (1985). On the multivariate asymptotic distribution <strong>of</strong> sequentialchi-square statistics. Psychometrika, 50(3), 253-263.Story, A., Walsh, C., Quinton, R., & Wynne-Edwards, K. (2000). Hormonal correlates <strong>of</strong> paternal responsivenessin new and expectant fathers. Evolution and Human Behavior, 21, 79-95.Teachman, J. D., & Heckert, A. (1985). The impact <strong>of</strong> age and children on remarriage: Further evidence. <strong>Journal</strong><strong>of</strong> Family Issues, 6, 185-203.van Ijzendoorn, M. H., & Sagi, A. (1999). <strong>Cross</strong>-cultural patterns <strong>of</strong> attachment. In J. Cassidy & P. H. Shaver(Eds.), Handbook <strong>of</strong> attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (pp. 713-734). New York:Guilford.Vandenberg, R. J., & Lance, C. E. (2000). A review and synthesis <strong>of</strong> the measurement invariance literature:Suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organizational Research Methods,3(1), 4-69.Wang, G. T. (1994). Social development and family formation in China. Family Perspective, 28, 283-301.Weisfeld, G. E., & Weisfeld, C. C. (2002). Marriage: An evolutionary perspective. Neuroendocrinology Letters,23(Suppl. 4), 47-54.Zavalloni, M. (1975). Social identity and the recoding <strong>of</strong> reality. International <strong>Journal</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Psychology</strong>, 10, 197-217.Todd Lucas is an assistant pr<strong>of</strong>essor in the Department <strong>of</strong> Family Medicine and Public Health Sciences–Division <strong>of</strong> Occupational and Environmental Health at Wayne State University. He recently completed apostdoctoral fellowship at the Center for Behavioral and Decision Sciences in Medicine (University <strong>of</strong>Michigan & Ann Arbor Veterans Affairs Hospital). In addition to cross-cultural measurement issues, hisresearch interests include social justice and psychosocial aspects <strong>of</strong> stress and health.Michele R. Parkhill is a postdoctoral fellow at the University <strong>of</strong> Washington. She received her PhD insocial psychology from Wayne State University. Her research interests include alcohol’s role in sexualassault and risky sexual behavior.Craig A. Wendorf is an associate pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> psychology at the University <strong>of</strong> Wisconsin–Stevens Point.He received his PhD in social psychology from Wayne State University. In addition to statistical modeling,his research interests include social justice and the psychology <strong>of</strong> teaching, learning, and assessment.E. Olcay I ⋅ mamoğlu is a pr<strong>of</strong>essor at the Middle East Technical University (METU), in Ankara, Turkey.She received her BS in psychology from METU, her MA in social psychology from the University <strong>of</strong> Iowa,and her PhD in developmental social psychology from Strathclyde University in Scotland. Her researchand theoretical interests include relationships between self, well-being, attachment–exploration orientations,value orientations, gender and marital relationships, and the social psychology <strong>of</strong> older adultsacross and within cultures.Carol C. Weisfeld received her PhD from the University <strong>of</strong> Chicago. She is a pr<strong>of</strong>essor at the University<strong>of</strong> Detroit Mercy. Her interests include female inhibition in mixed-sex competition.Downloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at College <strong>of</strong> St. Benedict/St. John's University on April 10, 2008© 2008 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Lucas et al. / MARITAL SATISFACTION INVARIANCE 123Glenn E. Weisfeld received his doctorate from the University <strong>of</strong> Chicago. He is a pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> psychology atWayne State University and president <strong>of</strong> the International Society for Human Ethology. His research andtheoretical interests include humor, kin recognition through olfaction, dominance, and adolescence.Jiliang Shen directs the Institute <strong>of</strong> Developmental <strong>Psychology</strong> at Beijing Normal University. His mainresearch interests are in scientific creativity and teacher pr<strong>of</strong>essional development. He is currently conductinga research project on cross-national comparisons <strong>of</strong> creativity.Downloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at College <strong>of</strong> St. Benedict/St. John's University on April 10, 2008© 2008 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.