Download issue (PDF) - Nieman Foundation - Harvard University

Download issue (PDF) - Nieman Foundation - Harvard University

Download issue (PDF) - Nieman Foundation - Harvard University

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

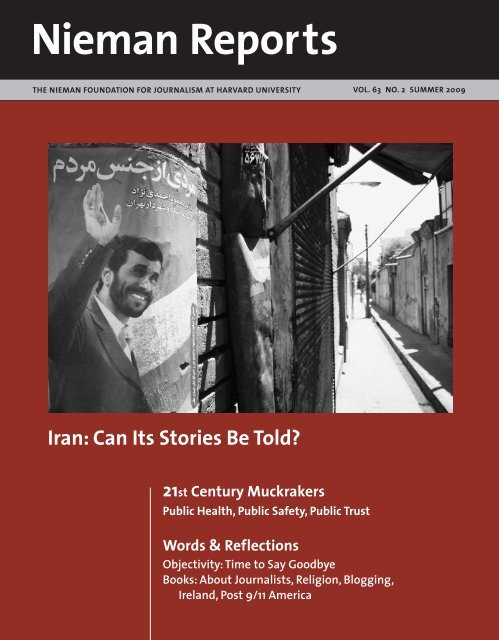

N ieman ReportsTHE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITYVOL. 63 NO. 2 SUMMER 2009Iran: Can Its Stories Be Told?21st Century MuckrakersPublic Health, Public Safety, Public TrustWords & ReflectionsObjectivity: Time to Say GoodbyeBooks: About Journalists, Religion, Blogging,Ireland, Post 9/11 America

N ieman ReportsTHE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY VOL. 63 NO. 2 SUMMER 20094Iran: Can Its Stories Be Told?Treatment of Journalists5 Understanding Iran: Reporters Who Do Are Exiled, Pressured or Jailed |By Iason Athanasiadis7 Journalism in a Semi-Despotic Society | Byline Withheld9 An Essay in Words and Photographs: Peering Inside Contemporary Iran |By Iason Athanasiadis14 When Eyes Get Averted: The Consequences of Misplaced Reporting |By Roya Hakakian15 Imprisoning Journalists Silences Others | By D. Parvaz17 ‘We Know Where You Live’ | By Maziar Bahari20 An Essay in Words and Photographs: A Visual Witness to Iran’s Revolution |By Reza26 Film in Iran: The Magazine and the Movies | By Houshang GolmakaniWomen Reporters, Women’s Stories28 Your Eyes Say That You Have Cried | By Masoud Behnoud29 Telling the Stories of Iranian Women’s Lives | By Shahla Sherkat30 Iranian Journalist: A Job With Few Options | By Roza EftekhariView From the West32 Seven Visas = Continuity of Reporting From Iran | By Barbara Slavin34 No Man’s Land Inside an Iranian Police Station | By Martha Raddatz35 The Human Lessons: They Lie at the Core of Reporting in Iran | By Laura Secor38 Iran: News Happens, But Fewer Journalists Are There to Report It | By Mark Seibel40 When the Predictable Overtakes the Real News About Iran | By Scheherezade FaramarziCover: Waving hello or goodbye?Iranian Presidential candidate MahmoudAhmadinejad in an electionposter from 2005 in the conservativeSouth Tehran district of Meidan-eShush. Ahmadinejad’s working-class,pious background and his experienceas mayor of Tehran allowed him tosweep most of the capital’s districtsin that election. Photo and caption byIason Athanasiadis.<strong>Nieman</strong> Reports Onlinewww.niemanreports.org

The Web and Iran: Digital Dialogue42 Attempting to Silence Iran’s ‘Weblogistan’ | By Mohamed Abdel Dayem46 The Virtual Iran Beat | By Kelly Golnoush Niknejad49 21st Century Muckrakers50 The Challenges and Opportunities of 21st Century Muckraking | By Mark Feldstein53 Investigating Health and Safety Issues—As Scientists Would | By Sam Roe55 Rotting Meat, Security Documents, and Corporal Punishment | By Dave Savini58 Mining the Coal Beat: Keeping Watch Over an ‘Outlaw’ Industry | By Ken Ward, Jr.62 Reporting Time and Resources Reveal a Hidden Source of Pollution |By Abrahm Lustgarten65 Pouring Meaning Into Numbers | By Blake Morrison and Brad Heath67 Navigating Through the Biofuels Jungle | By Elizabeth McCarthy70 Going to Where the Fish Are Disappearing | By Sven Bergman, Joachim Dyfvermark,and Fredrik Laurin74 Watchdogging Public Corruption: A Newspaper Unearths Patterns of Costly Abuse |By Sandra Peddie76 Filling a Local Void: J-School Students Tackle Watchdog Reporting |By Maggie Mulvihill and Joe BergantinoWords & Reflections78 Objectivity: It’s Time to Say Goodbye | By John H. McManus80 Worshipping the Values of Journalism | By John Schmalzbauer82 When Belief Overrides the Ethics of Journalism | By Sandi Dolbee83 Religion and the Press: Always Complicated, Now Chaotic | By Mark Silk85 Journalists Use Novels to Reveal What Reporting Doesn’t Say | By Matt Beynon Rees86 Life Being Lived in Quintessential Irish Moments | By Rosita Boland91 An Enduring Story—With Lessons for Journalists Today | By Graciela Mochkofsky93 They Blog, I Blog, We All Blog | By Danny Schechter95 Fortunate Son: The Life and Times of Hunter S. Thompson | By Adam Reilly97 The American Homeland: Visualizing Our Sense of Security | By Nina Berman3 Curator’s Corner: The Journey of the 2009 <strong>Nieman</strong> Fellows—And of the <strong>Foundation</strong> |By Bob Giles101 <strong>Nieman</strong> Notes | Compiled by Lois Fiore101 Jobs Change or Vanish: <strong>Nieman</strong>s Discover an Unanticipated Bonus in Community Work |By Jim Boyd104 Class Notes2 <strong>Nieman</strong> Reports | Summer 2009

Curator’s CornerThe Journey of the 2009 <strong>Nieman</strong> Fellows—And ofthe <strong>Foundation</strong>In their experiences, conversations and future directions, they create a portrait ofwhat is happening in journalism today.BY BOB GILESDramatic changes in the world of journalism weighedheavily on the lives and outlook of the <strong>Nieman</strong> classof 2009: news of layoffs from their newsrooms (andof one of their newspapers disappearing), worry about thefuture of newspapers, uncertainty about their own pathsas journalists. Even as fellows wrestled with these realities,what remained firm was their knowledge that journalismis essential as a bulwark of democracy. Over time, thetransformative nature of the <strong>Nieman</strong> experience broadenedtheir outlook, encouraging them to envision rolesin journalism’s future and finding their places in it. Theylearned how emerging technologies enable connectionswith larger and well-targeted audiences while at the sametime empowering them to tell their stories on multipleplatforms and to interact more directly with the publicwhile still adhering to journalism’s core values.The fellows also found many supportive voices joiningthe conversation throughout the year speaking to the valueof journalism. Following a ceremony at Lippmann House,when the fellows received certificates for completion oftheir fellowships, <strong>Harvard</strong> <strong>University</strong> President Drew Fausturged them to use the digital tools wisely in moving pastthe mere rapid transmission of information into the tougherwork of ensuring understanding. “Go forth,” she said, “tochange the world not only in a way that will enable us tosurvive but to thrive.”A few days earlier, Martin Baron, editor of The BostonGlobe, had reminded the fellows that “Good journalism,as you know, does not come cheap. The most powerfuljournalism—breakthrough journalism—can be shockinglyexpensive.” He warned that the “end of reporting that requiresa major investment of resources … means we willsee a huge void in American journalism. And it will allowpeople who are powerful, or crafty, or both, to engage inwrongdoing without fear of being held accountable.”That same evening, the <strong>Nieman</strong> class honored one ofits own, Fatima Tlisova, with the Louis M. Lyons Awardfor Conscience and Integrity in Journalism. In presentingthe award to Fatima, a brave reporter and sensitive spirit,David Jackson, her classmate, said that we were bearingwitness to the reality that “no government can commit seriouscrimes against its own citizens—can practice abduction,torture or genocide—without first silencing the press.” [Onpage 49 are descriptions of Tlisova’s investigative reportingwith excerpts from remarks she and Jackson made at theLyons Award ceremony.]Tlisova, like many journalists, is at risk in her homeland,and she knows a life of struggle lies ahead by retainingher dedication to bearing witness. Like her, many <strong>Nieman</strong>Fellows come from nations torn by conflict and often inthe grip of authoritarian rulers employing repressive measuresto restrict press independence and freedom. For ayear, they live in what Jackson called a “privileged exile.”For them, uncertainties lie ahead as they weigh the risksof returning home against the difficulties of finding waysto stay in the safe sanctuary that America offers.In this time of challenge and crisis for journalists andlegacy news organizations, the <strong>Nieman</strong> <strong>Foundation</strong> remainsfundamentally optimistic. Our fellowship program is forwardlooking—providing fellows with the all-too-rare opportunitytoday of being able to think deeply and reflect on how theycan best contribute to journalism’s future while fosteringthe values of excellence and high purpose.Throughout its existence, the foundation has spoken ina variety of ways to the widening range and of journalism’spossibilities.• Since the first <strong>issue</strong> of <strong>Nieman</strong> Reports was published in1947, it has been fulfilling its founding purpose: to explorethe responsibilities of the press and expand understandingabout how journalism can be strengthened.• The <strong>Nieman</strong> Watchdog project revolves around the ideathat asking the right questions lies at the core of meaningfuljournalism. In serving as a surrogate for the public,the press is obliged to ask probing questions, from townmeetings to the state house to the White House.• On the Narrative Digest, well reported, powerfully writtenstories demonstrate why long-form journalism matters asa way of conveying deeper understanding. Here excellentstorytelling is showcased and its methods explained.• The <strong>Nieman</strong> Journalism Lab, launched last fall in responseto industry’s search for workable business models forjournalism in the era of digital media, provides real timeupdates on the rapidly shifting ground on which journalismis rebuilding.These endeavors speak to the enduring principles ofquality journalism. At a time when some believe the bestof times are in the rearview mirror, the paths that lie aheadfor this year’s fellows and for the foundation—while sureto be bumpier than usual—are embedded in promise. <strong>Nieman</strong> Reports | Summer 2009 3

Iran: Can Its Stories Be Told?On a spring afternoon, Iason Athanasiadis, then in his <strong>Nieman</strong> year and a photojournalistwho’d worked in Tehran for three years before arriving in Cambridge,urged me to have <strong>Nieman</strong> Reports illuminate the ways in which Iranian andWestern journalists and those who carry dual citizenship work in Iran. His visionwas of a wide-ranging exploration of on-the-ground reporting. A year later,stories woven with threads of reporting experiences remind us of why it’s difficultfor outsiders to truly understand what is happening in Iran.Roya Hakakian grew up in postrevolutionary Iran. Now, as an Iranian-Americanauthor and journalist, she yearns for a clearer view of her homeland toemerge. “Poor reporting from and about Iran has kept the West in the dark,” shewrites. “In this lightlessness, Iranians are rendered as ghosts.”Wearing an Iranian flag, a Metallica T-shirt, and bandannassupporting reformist candidate Mostafa Moein, twofriends attended a 2005 pre-election rally in a Tehransoccer stadium. Photo by Iason Athanasiadis.Journalists still pushagainst boundaries of whatIran permits to tell what ishappening there. Doing soinvites the tactics of intimidation,threats and interrogationsand the risk ofimprisonment, banishment,torture and, in some cases,death. A reporter who hasbeen imprisoned and is writingwithout a byline says: “Itis undecided life, with therisks taken being unpredictable,since its press law isopen to interpretation. Punishment for breaking the law depends on many things,too, including who you are and what your job is.” Another reporter sent us ane-mail to explain why words intended for our pages would not be on them: “If itwas a better time, I would have done it. I am under a lot of psychological pressure,and I am trying not to let it affect my work. My neighbors keep getting callsfrom security officials who tell them that I am involved in drug smuggling. I amassuming that they want to intimidate me with embarrassing charges before theelection.”Others in our <strong>Nieman</strong> family provided invaluable guidance, and I am gratefulto them. Roza Eftekhari, once an editor at Zanan, a women’s magazine in Iranbanned in 2007 by the Press Supervisory Board, reached out to Iranian journalistsand asked them to write for this <strong>issue</strong>. She also found a Farsi translator,Semira Noelani Nikou, a 22-year-old student at Scripps College. Hannah Allam,Scheherezade Faramarzi, Dorothy Parvaz, <strong>Nieman</strong> Fellows in this year’s class,generously offered advice, with Scheherezade and Parvaz, both with family ties toIran, joining their words to our pages, giving a gift to us all. —Melissa Ludtke4 <strong>Nieman</strong> Reports | Summer 2009

IRAN | Treatment of JournalistsUnderstanding Iran: Reporters Who Do AreExiled, Pressured or Jailed‘Roxana’s work consistently gave the lie to the narrative of amonolithic Islamic Republic.’BY IASON ATHANASIADISRoxana Saberi (right) with a friend in Tehran in 2006. Photo by Iason Athanasiadis.On May 10th, an appeals courtin Iran suspended the prison sentenceof American-Iranian journalistRoxana Saberi, who hadbeen held in detention for morethan three months. After beingreleased from jail, she returned tothe United States. In mid-April,Iran’s Revolutionary Court hadcharged her with spying for theUnited States and sentencedher to eight years in prison.This essay was written duringthe time Saberi was in Tehran’sEvin Prison about her and thechallenging circumstances underwhich she and other journalistswork in Iran.She joined our improbablegroup halfway through theacademic year and stuck itout until the end. In class shewas calm, courteous and reserved.Her notes were assiduous, herquestions intelligent. But sherefrained from the cut-and-thrustthat the rest of us thrilled in engagingin with our rather seriousforeign ministry professors.Roxana Saberi was selfpossessed,unflappable andinscrutable.We were a strange group evenbefore Roxana, the Japanese-Iranian-American broadcastjournalist beauty queen, joinedus. There was a blonde ScottishOxford graduate who managedto combine the flimsiestof mandatory headscarfs withsuperb Persian delivered in anupper-crust British drawl; anAmerican jurist who enthusiasticallyembraced her suffocating,government-mandated hijab longafter it was spelled out to her thatshe could get away with less; alikeable South African diplomatin a perennial black “ReservoirDogs” suit and string tie whowas quiet for weeks at a timeaside from occasional eruptionsinto frustrated, anti-imperialistscreeds; a devout Saudi whosenationality was revoked aftershe met a Shi’ite Iranian fellowstudent at a university in theUnited States, married him andmoved to Iran, and a Turkishdiplomat about whom we learnedvery little except that he likedIranian kebabs.Roxana floated serenely overour rambunctiousness. Shehanded in her assignments ontime, even while struggling tomake ends meet as a freelancecorrespondent. Just before theend of the year, she receiveda summons to the ministry ofeducation. If only such Sisypheanharassment of foreign studentswasn’t the bread-and-circus ofIran’s rambling bureaucracy,the incident might have beenprophetic.Patient, punctual and selfpossessed,Roxana went to the<strong>Nieman</strong> Reports | Summer 2009 5

Iranmeeting. But the person she was supposedto see was not there, nor wouldhe be back that day, an assistant toldher as if arranging a meeting, skippingout on it, and then denying itsexistence was the most natural thingin the world. This charade played outa few more times until Roxana wastold the reason behind her summoning:As a journalist, she was ineligibleby Iranian law to receive her master’sdegree.No apparent logic was offered toexplain the verdict. After all of herhard work, Roxana was denied herdegree because of an unknown technicality.She knew how the systemworked and that she could do nothingabout it. She just had to put herhead down and deal with it. As myendlessly frustrated Iranian friendsnever tired of reminding me, logiccontrols little in Iran.This denial was only one of manyfrustrations imposed on Roxana as shestruggled to live for her first time inIran, work and reconcile her Iranianand Japanese identities with an Americanupbringing in North Dakota. WhenBBC World took her on in 2006 forthe post of second correspondent, itwas a long-awaited break. But a fewmonths later, her accreditation wasrevoked and she was forced to returnto low-profile freelancing.Whenever I saw her, Roxana neverbetrayed the difficulties she was goingthrough. She was always willing to help,pass on a contact, or inquire about myproblems. She never mentioned thatshe was working on a book. But judgingby her stoic character, a book she wrotewould almost certainly have avoidedthe self-indulgencies of so many otherexpat memoirs that focus on personaljourneys of self-discovery rather thanthe extraordinary, wonderful anddeeply frustrating society that usuallyjust provides the background.Meanwhile, Roxana, her turquoiseheadscarf, videocamera and tripodwere a fixture at press events. Her fluentPersian allowed her to give the kindof deep insight into the human sideof Iran that is intentionally strippedaway from the bombastic statementsabout Israel, threats to shut downIntense international pressure was exerted by journalists and political leaders to urge theIranians to release Roxana Saberi, which happened on May 10th.the Persian Gulf, or announcementof fresh technological leaps.Language, Meaning andDepthTherein lies the rub. Roxana’s workconsistently gave the lie to the narrativeof a monolithic Islamic Republic. Itwent counter to the tension-escalatingscript that sees journalists focuson hard-line prayer sermons, anti-American demonstrations—dominatedby government civil servants—andsuicide-bomber registration drives,in which “bombers” register but don’tcarry out an operation. It’s all partof Tehran’s never-ending baiting ofWashington.Roxana was no spy. Anyone who hasexperienced the difficulty of workingas a journalist in Iran can tell you thatresearching a balanced story about thenuclear <strong>issue</strong>, let alone infiltrating theIslamic Republic’s deepest secrets, isnear impossible. But Roxana was sogood at what she did as to become athorn. Her work cut away from theherd to focus on Iran’s tumultuousand deeply fascinating society. Howdisruptive this must have been forthe regime’s painstakingly constructedimage of a stiff upper-lipped Islamicsociety dedicated to revolutionary idealsrather than the proliferating plasmaTVs and home appliances over whichIran’s materialistic postwar middleclass (post-sanctions, they are now alsonouveaux pauvre) salivate over.There is a constant to Iran expellingjournalists once they become too wellversed in the country. HyphenatedIranians, who cannot be expelled,instead experience the pressure beingratcheted up on them until residencethere becomes unbearable.Iran turned into a security stateafter the 2005 election of MahmoudAhmadinejad. Sanctions were imposed,the covert intelligence war between theIslamic Republic and the West swelled,and the authorities announced theyhad broken up several intelligencenetworks and carried out repeatedsweeps of dissidents. Workers’ protestsand a number of unexplainedexplosions rocked the country from2005 onwards, putting the regime onedge. As correspondents for AgenceFrance-Presse, The Associated Press,The Independent, The Guardian, andthe Financial Times were barred, the6 <strong>Nieman</strong> Reports | Summer 2009

Treatment of Journalistsforeign journalist exodus began.Far better, Iran’s sphinx like bureaucratsthought, to give finite visitorvisas to clueless, non-Persian speakingforeigners than to have permanentlyaccredited (and bothersome) correspondentsunderstanding the countryand its culture. Instead, these outsiderswould scoot around the Tehran-Qom-Isfahan triangle with theirstate-appointed guide, breathlesslyinterview a few regime-sanctionedreformists, indulge in some surreptitiousflirting with Iran’s abundance ofluscious womanhood, and come awaymouthing similar platitudes about this“complex civilization,” “paradoxical”country, and “layered” society.By summer 2007, Roxana, workingwithout a press permit, was one of avery few journalists still surveying thescene. The night before I left Iran in2007, an Iranian political analyst fora foreign embassy told me that theIranian government abhors foreignjournalists, who are seen as proffering“social intelligence” about their hostcountry. Unlike truly locked-awaylands such as North Korea, Iran is anopen society proud of its contributionto world civilization. But the currentsecurity-minded regime wants to minimizethe outflow of information.Despite the abundance of informationavailable about Iranian society,CIA agents allegedly speak TajikaccentedPersian, the kind of hillbillysquawk that might secure them roadconstructionjobs in provincial Iranbut probably not high-level politicalaccess. Over at Langley, they watchIranian cinema for clues about thetarget society or fish for scraps of informationamid the exile communitiesin Los Angeles, Dubai and Baku.The security-minded Ahmadinejadadministration has sought to shutout information gathering of eventhe most innocent kind, an attitudediametrically opposed to the earlierKhatami administration’s emphasison debate and openness. But even ifthe hard-line trend is now dominant—egged on by the Bush administration’sprovocative and threatening maneuversamong Iran’s neighbors and Pentagoncovert operations within its borders—journalists should not become sacrificiallambs.Roxana and other journalists whoreside in Tehran were massively hamperedby existing in a state that viewedthem as official spies. That was barrierenough to considering a freelance careeras an intelligence informant. Butwhat Roxana’s case reminds us—asidefrom the great disservice it did to Iran’sreputation—is that in our increasinglyintertwined world journalists are notconsidered a protected species buttreated as fair game. Iason Athanasiadis, a 2008 <strong>Nieman</strong>Fellow and a freelance journalist inIran between 2004 and 2007, wrotethis article for The National, publishedin Abu Dhabi in the UnitedArab Emirates.Journalism in a Semi-Despotic Society‘Censorship, low payment, and the high risk of arrest for any journalistwho dares to take an investigative step, among other reasons such as lackof individual liberty, have pushed Iranian journalists to the virtual worldof the Internet.’This article is written by a journalistin Iran. No byline appears on it due tothe situation this journalist confrontswhile working. This journalist has donereporting for Western television.To be on the safe side, it is advisableto apply the prefix “semi” indescribing events, politics, NGOsand journalism in Iran. “Here is nota democracy, but ‘semi’ democracy,”some write. For others, “It is not ademocratic, but a dynamic society.”Sentences like these are used by nearlyevery Western journalist visiting Iranto describe the society safely whilebeing certain of securing their nextpress visa and satisfying the curiosityof readers in Europe, Asia and theUnited States.But how does it feel to live andwork in a “semi” society? It is undecidedlife, with the risks taken beingunpredictable, since its press law isopen to interpretation. Punishmentfor breaking the law depends on manythings, too, including who you areand what your job is. For example, ablogger or print journalist committingthe same crime might end up withdifferent verdicts. A former classmatein high school writes for roozonline.com, a news wire based in Europe thatis moderate in criticism. She is notarrested, though she lives in Tehran.Another person, writing for the samepublication, ended up in jail, was bailedout and had to escape Iran.Reporters, when arrested, canend up in solitary confinement inthe notorious Evin Prison. In fact,this is usually where journalists andbloggers are locked up at first for acouple of weeks or months. If they letthemselves be co-opted, agree to actas a collaborator after being bailedout, or bid farewell to journalism andgo abroad, their cooperation labelsthem as good or tolerable journalists.They can achieve this by volunteeringinformation about their contacts orthose they’ve interviewed, or even tellthe interrogators about like-mindedfriends.<strong>Nieman</strong> Reports | Summer 2009 7

IranThe income “good” journalists canearn is so meager (around $500 amonth) that they are forced to compromisetheir professionalism by being anadvertising agent or by wheeling anddealing in planting favorable reportingto business or consumer goods. Manytimes one of my coworkers at my dailypublication wrote letters in Farsi andEnglish to Nestlé or other companiesin Iran to negotiate the marketing ofproducts under the excuse of writing“health or food stuff ” pieces. Collusioninvolving moneymaking is also foundamong sports writers. The sports pageshave among the highest readership, anddozens of male sportswriters are in jailbecause they’ve been involved in fixingmatches or, in most of these cases,served as brokers in selling and buyingsoccer and basketball players.Self-censorship: To write in Farsi is topush internalized red lines from thesubconscious to conscious. Those wellversed in the ways of self-censorshiptransgress these red areas unknowinglyin the same way a soldier findshis way through a minefield. A wellexperiencedjournalist is defined in thisinstance as “a person who can say whathe means in a way that the friends(audience) can get the point and theenemies (censors and pressure groups)miss the point.” Another effective formof self-censorship involves distractingthe focus of the audience (includingwriters at the dailies) to the disastrouswoes of the current economic crisis inthe United States, in particular, andthe West, in general.Heaping invectives on the U.S. administrationand its misconduct canalso be a way of continuing to workas a journalist while staying out ofjail. Another tricky way to do this isto take advantage of the dichotomyof so-called reformist and conservativecamps by acting as a journalistwith impartiality. In short, whateveris written should prove that you area strong believer in the ruling establishmentand you see eye to eye withthe supreme leader, Ayatollah AliKhamenei. When you are seen as asympathizer to the regime, you cancriticize the incumbent government.Translating Western newspaper articlescan be used as a safety valve to saywhat you mean through other stories,for example about Turk or Arab societiesor regimes.Postal costs and subsidized dailies:The cost of publishing nearly all ofIran’s daily newspapers is subsidizedby low interest loans. With monthly orweekly magazines (with the exceptionof the “yellow” press, 1 ) subscribers arediminishing in number as people loseinterest in reading what they considerto be old and outdated articles andanalysis, since many of these publicationscontain no firsthand reports. Andpostal costs have recently been almosttripled, which has only worsened thissituation—a monthly magazine thatcosts less than one dollar now costsalmost three dollars to be mailed.As one well versed journalist said,this additional cost has been the“finisher bullet” to any independentperiodicals.Lack of newspaper readership: Historically,with its low readership andcirculation of dailies, Iranians do notrely on newspapers to get information.In fact, daily reporting of news abouthuman events is not what the averagecitizen seeks. The Hamshahri (Citizen),the city of Tehran’s mouthpiece withthe highest circulation of around halfa million a day, is not sold for its newscontent but for its advertisements, realestate vacancies, and eulogies of thedead. Voice of America (VOA) andmore recently BBC Persian (on radioand TV) and the Internet throughproxies are the main sources for newsfor urban residents. To understandhow small the impact of newspapersis, I remind you that for more thantwo weeks during the New Year holidays,which started on March 21st, nonewspapers were published, and theirabsence was not felt at all.Movement toward the Internet: Censorship,low payment, and the high riskof arrest for any journalist who daresto take an investigative step, amongother reasons such as lack of individualliberty, have pushed Iranian journaliststo the virtual world of the Internet.This is happening even though theadviser to Tehran’s general prosecutorhas said that Iranian officials blockedabout five million Web sites in 2008.This has forced some of these digitaljournalists to look for jobs at Radio FreeEurope/Radio Liberty (Radio Farda),VOA and BBC Persian, or simply seeka nonjournalistic or public relationsjob to promote goods rather than actas the conscience of public opinion.Some create their own independentpress, if it is possible to do so. [Seearticles about the Web and Iran onpages 42-48.]I used to see many of my journalismcolleagues at Café Godot (named afterBeckett’s play) near the <strong>University</strong> ofTehran; now I read their bylines orhear their voices in Radio Farda, BBCPersian, or VOA. Those who are likeme—a young journalist who remainsin Iran—have to write as a sycophanticjournalist, finding some way to castigatethe United States and Westernsociety, in general, while at the sametime saying something between thelines. This is not journalism, rather itis compromising one’s principles day inand day out. However, when journalistsdare to write under pseudonymsfor any Persian news wires outside ofIran, they will face a harsh punishment,such as happened with Sohail Asefi,who escaped, Nader Karimi, who isstill in jail, Omidreza Mirsayafi, whodied in jail [more information abouthis death is on page 44], and dozensof others who still are kept in EvinPrison. 1The “yellow press” is a popular name for newspapers and periodicals of the early20th century that published news stories of a vulgarly sensational nature, a namesynonymous with gutter press.8 <strong>Nieman</strong> Reports | Summer 2009

Treatment of JournalistsAN ESSAY IN WORDS AND PHOTOGRAPHSPeering Inside Contemporary IranBY IASON ATHANASIADISA little girl looks out from a crowd of chador-covered women during a fireritual that tens of thousands of women perform on the eve of the Shi’itefestival of Ashura in the town of Khorramabad in western Iran. Ashurais part of mainstream Shi’ite Islam but, similar to Sufism, certain of itsrituals approach a mystic plateau that has led orthodox Muslim scholarsto condemn them.An exhibit of photographs of Iran featuringthe work of Iason Athanasiadis,a 2008 <strong>Nieman</strong> Fellow, opened for athree-month show in January at theCraft and Folk Art Museum (CAFAM)in Los Angeles, California. “Exploringthe Other: Contemporary Iran,”the title Athanasiadis selected for hiscollection, became the first exhibit ofpolitical photography from Iran to beshown at an American museum sincethe 1979 Islamic Revolution. NowAthanasiadis is contributing some ofthe exhibit’s photographs, along withothers he took during the years whenhe lived and worked in Iran, to thepages of <strong>Nieman</strong> Reports. His wordsthat accompany these photographswere written for CAFAM’s newsletterto introduce his show and explain howa photojournalist created an “artisticmuseum show about Iran.” On the followingpage, this introduction appearsin a reworked version.<strong>Nieman</strong> Reports | Summer 2009 9

IranGiant placards of the former and current supreme leaders of theIslamic Republic tower over the 100,000 seat Azadi Stadium inwestern Tehran during a soccer game. January 2006. Photo andtext by Iason Athanasiadis.It is the most hypothetical newsstory topping the internationalnews agenda today. Is the IslamicRepublic of Iran pursuing a nuclearbomb? Is it seeking to dominate thePersian Gulf? Sometimes it gets difficultto find the fire amid all thesmoke of headlines and the heat ofrhetoric.Speculation and demonization consistentlydrown out the Middle East’smost ethnically and religiously diverseculture. They obscure landscapes ofrare variety and geological beautypulsating with color and a rare light.Iran’s mystical topography is the settingfor a struggle between traditionand modernity that has been a constantof the modern era, first duringthe Qajar and Pahlavi empires, thenthroughout the three-decade lifespanof the Islamic Republic.I come from Greece, a countryas rich in heritage and as culturallyfractious as Iran. Moving to Tehranin 2004, I was struck by our sharedexperience of forming modern identities.Old civilizations find it particularlyawkward to adapt to a rational presentwhere culture and tradition standfor little, countries where indigenousreligions—Greek polytheism and IranianZoroastrianism—are overshadowedby the doctrines of Christianityand Islam.Greece and Iran have both beencrossroads and laboratories for experimentsin social conditioning. In Iran,the most radical consequence of thiscultural struggle was the 1979 IslamicRevolution, when social, religious andeconomic agendas collided. Perhaps themost visible outcome of this battle wasthe forceful imposition of state-sanctionedfaith and the marginalizationof indigenous traditions. Whether inthe form of churches planted on top ofmarble temples or Zoroastrian shrinestransformed into imamzadehs (burialshrines for Shi’ite saints), cultural historywas whitewashed to make roomfor a new national narrative.While living in Iran, I photographedthe country from the perspective ofcharting two great civilizations’ sharednarratives and divergent fates. Thisphoto essay reflects where the Iranianexperiment at theocracy stands on theeve of its 30th anniversary. 10 <strong>Nieman</strong> Reports | Summer 2009

Treatment of JournalistsKurdish villagers head back to Horamane Takht in western Iranafter a Sufi ceremony in a graveyard on the outskirts of the village.Photo and text by Iason Athanasiadis.<strong>Nieman</strong> Reports | Summer 2009 11

IranTraditional women in Hormozgan Province walk along the BandarAbbas-Jask route in the baking midday heat. Their peasant dressescontrast anachronistically against the heavy lorries transportingcut-price Chinese goods on the international highway west. Photoand text by Iason Athanasiadis.Iason Athanasiadis is a writer, photographer, filmmaker and TV producer whohas been reporting from the Middle East, Central Asia, and the southeast Mediterraneanfor various news organizations during the past decade. He covered the2003 invasion of Iraq from Qatar for Al Jazeera, the 2004 Athens Olympics forBBC World, and the 2006 Israeli-Hizbullah war in Lebanon as a freelancer.12 <strong>Nieman</strong> Reports | Summer 2009

Treatment of JournalistsDead soldiers look out of aging photographs in Golestan-eShohada, a male-only martyrs cemetery in Isfahan.Young women practice the mystical sama whirling dance in Tehran’sVelinjak district. Sufism has flourished in urban areas over the past fewyears, far beyond its traditional heartlands in Khorassan, Kerman andKordestan Provinces. Buddhism, Christianity and yoga retreats alsoare increasingly popular. Photos and text by Iason Athanasiadis. <strong>Nieman</strong> Reports | Summer 2009 13

IranWhen Eyes Get Averted: The Consequences ofMisplaced Reporting‘Poor reporting from and about Iran has kept the West in the dark. In thislightlessness, Iranians are rendered as ghosts.’BY ROYA HAKAKIANOn the day that the Iranian-American journalist RoxanaSaberi, charged with espionageby Tehran, was handed her eight-yearsentence, I received several dozenmessages asking if I planned to writesomething about the case. It is a naturalquestion for those who know me:I am Iranian. I write about Iran, andI often write what in journalism werefer to as human-interest stories. Yetas certain as I was about Saberi’s innocence,I refused to write only abouther. That would be precisely whatTehran’s ruling puppeteers wantedeveryone to do. And I am, above all,a writer, not a marionette.I am also an American. I believein our goodness and in our genuinedesire to learn the truth. I reject myIranian compatriots’ conspiratorialviews about Big Brother’s hold onour media. Yet I cannot quite explainwhy the coverage of Iran in our pressis so profoundly inadequate. Everyweek, so many hundreds of articlesare written about Iran’s nuclear programthat yellow cake now has theappeal of pastry to our palette, andits top chef, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad,is watched just as avidly. Espionageis cheap in Iran, and hundreds arecharged with it every year, but few“spies” become household names. WithIran’s presidential election only weeksaway, as I write this, I hardly call ita coincidence.Events Overshadow StoriesTyrannies are born in crisis. Theythrive on crisis. Iran is no different.From its inception, the regime understoodthe value of a grand spectacle,and it has staged and exploited manyever since.On November 4, 1979, the day theAmerican embassy in Tehran wasseized, the world’s attention becamesolely focused on the fate of the 52American hostages thereafter. ThatPrime Minister Mehdi Bazargan, inprotesting the takeover, resigned andhis highly liberal cabinet collapsed wasscarcely captured by the foreign lenses.Neither were the subsequent executionof the foreign minister, SadeghGhotbzadeh, and the arrest of thegovernment spokesman, Abbas Amir-Entezam, on the charges of espionagefor the United States, a pattern that,astonishingly, still continues, as doesAmir-Entezm’s detention.The American hostages sufferedgreatly, yet were released after 444days. But Iran’s political landscapewas never the same in the aftermathof the takeover. While the world wasconsumed by the captive Americans,the hardliners in Iran, ceasing uponthe global oblivion, obliterated theopposition—exiled, imprisoned andexecuted them—and implemented therepressive laws, including the Islamicdress code for women, which theyhad not been able to pass in the earlymonths after the 1979 revolution.Then came another leviathan crisis:the war with Iraq. Four years into theordeal, when Saddam’s bombs hadreached Tehran, I was standing onqueue to receive our monthly allotmentof eggs and other staples fromthe local mosque, when a neighborcomplained of the shortages and theincessant shriek of sirens. A RevolutionaryGuard member barked at himwith a rejoinder, not unlike what theneocons used against those critical ofthe Patriotic Act: It was unpatriotic,even un-Islamic, to complain whenthe country was at war.With eyes averted to the war, drovesof political prisoners were executed,even against the advice of the country’ssecond greatest clergyman, AyatollahMontazeri. By August 1988, severalthousand prisoners, even some whohad nearly served their terms andwere on the brink of release, werekilled in the span of days. Montazerihad pleaded with the authorities to atleast wait until after the holy monthof Moharram had passed. But he wastold that too many preparations hadbeen put in place to stop the bloodshed.Because of his vehement objections,Montazeri, once in line to replaceAyatollah Khomeini as the supremeleader, has ever since been banishedto his quarters in Qom, Iran.The mass, nameless grave, wherethe relatives of the dead gather everySeptember to remember their lovedones, is called Khavaran, a corner ofTehran’s main cemetery that the officialshave dubbed “the Damnedville.”The thousands who lie there nevermade it to the headlines that Augustbecause in July, the USS Vincennesshot down an Iranian Airbus killing290 passengers and crew aboard.Oblivion reigned once more, and theexecutioners ruled.After the end of the Iran-Iraq warin late 1988, there was a new sensation.Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Versestook center stage, and the authorsingularly commanded the thousandsof headlines that the dead never did.The word “fatwa” entered the popularlexicon. It was just the kind of dramathe regime has always cherished: TheWest was riled up, and the dispossessedin the Muslim world, to whom Iran14 <strong>Nieman</strong> Reports | Summer 2009

Treatment of Journalistsincreasingly appeared as pioneeringtheir cause, were electrified. Ironically,it was the fair-minded Rushdiehimself who began to speak on behalfof those dead and all the other talesthat were going unreported.Absence of Good ReportingI revisit this history, in part, becauseit is ongoing but more importantlybecause it has far greater implicationsthan we realize. Poor reporting fromand about Iran has kept the West inthe dark. In this lightlessness, Iraniansare rendered as ghosts. Yet it is notfor altruism, the mere defense of apeople’s dignity, that we must changeour ways of telling the news of Iran.Rather, it is the ubiquitous encroachmentof that darkness, even upon ourleaders, that makes it an essentialmandate, a point that veteran foreignpolicymakers, such as Richard N. Haassand Martin S. Indyk, formulate inthis way: “The United States simplylacks the knowledge and the guile to[influence] Iran effectively.”Diplomats are human. They, too,must gather information in much thesame way as the rest of us, only theyhave the disadvantage of having accessto dubious sources such as the CIA.They, too, often rely on reporters. Theabsence of good reporting is one reasonwhy Iran remains an enigma for theelite and ordinary readers alike.That is not all. Our inadequate reportingis also, in part, the reason forthe inexplicable stagnation in Iran’s reformmovement. Iranians know that theoutlandish rhetoric of their unpopularleaders capture the imaginations farmore than the tales of their resistanceagainst those leaders. When Iran’sPresident Mahmoud Ahmadinejadproposes to hold a Holocaust cartoonexhibit, thousands of headlines reporthis intentions. But when the exhibitgoes on and its halls go unfrequented,scant items tell of the nation’s bottomlessdisinterest in their president’sfollies. When he speaks against Israel,the world stands at attention. Butwhen he arrests journalists, writersand intellectuals who criticize theirown government for diverting muchneeded funds at home to Hamas andHizbullah, the lede, if written at all,is buried in a footnote.In February 2006, when thereseemed to be nothing but outrageagainst the Danish cartoons comingout of the Middle East, a bus strikeas significant as Montgomery, Alabama’sbus boycott brought Tehranto a standstill. Hundreds of driversrefused to work, and idle buses linedthe terminals as far as the eye couldsee. But the only images that appearedon the evening news in the West werethose of a handful of hoodlums protestingin front of Denmark’s embassy,throwing stones and smirking for thecameras.Conscientious Americans alwaysrant about the apathy of their fellowAmericans. Iranians of all stripesalways speak of despair among theirpeople. Apathy and despair are amongthe offspring of oblivion. The hundredsof teenage girls and young womenwho stormed the Haft-e-Tir Squarein Tehran in June 2006 to demandan end to gender apartheid in theircountry in a movement that has cometo be known as the “One Million SignatureCampaign” might as well havestayed home and killed their everyhope because their presence, theirsubsequent arrests and imprisonment,went unrecorded. It was not reportedin the American media until 2009.Three years is an eternity for a20 year old to know that others arenot deaf to her, to keep herself fromwondering if she is not mute, or if herexistence matters. Roya Hakakian is the author of “JourneyFrom the Land of No: A GirlhoodCaught in Revolutionary Iran,” hermemoir of growing up as a Jewishteenager in postrevolutionary Iran,published by Crown in 2004. She receiveda 2008 Guggenheim fellowshipin nonfiction.Imprisoning Journalists Silences OthersWhile most Iranian journalists have to operate with extreme caution, foreignjournalists can be more frank on the <strong>issue</strong>s they face in Iran.BY D. PARVAZSecrecy, fear and a random justicesystem are together the currencyof oppression. This is how agovernment typically attempts to buysilence and compliance. And the caseof Roxana Saberi, a journalist whowas detained in Iran in January, is aclassic example of this semisuccessfulstrategy.Arrests such as Saberi’s don’t justsilence the imprisoned party. Theycreate a freeze, a nooselike hold onIranian journalists, both domestic andinternational. It’s incredibly risky fora journalist holding an Iranian passportto speak the truth about what itmeans to work in Iran without riskinglife and liberty.Initial stories indicated that Saberiwas picked up on suspicion of purchasinga bottle of wine, which, likeall alcohol, is prohibited in Iran. Itwas later reported that she had beenworking as a journalist on an expiredor revoked permit since 2006 (an exceptionallyreckless thing for a wouldbespy to do). Saberi was ultimately<strong>Nieman</strong> Reports | Summer 2009 15

IranIn late April, with Roxana Saberi still jailed in Iran, members of Reporters Without Bordersheld placards with her picture outside the IranAir office in Paris. Photo by MichelEuler/The Associated Press.charged with espionage in March and,after a brief, closed trial received aneight-year prison sentence. Throughher appeal, the American-born reporterwas released in May.Now, according to Iranian presslaws, reporting without a permit equalsillegally gathering news. This can leadto suspicion of spying, especially whenthe journalist in question reports forforeign media. Iranian authorities saySaberi confessed to the charges againsther, though if she confessed to anythingat all, it might have been onlyto working without a permit. Besides,confessing to crimes not committedis pretty much a national pastime.Iranians who are hauled into policestations for various alleged infractionsoften have the option of writingand signing letters of confession andapology. These letters are kept on fileand can be held against the individualon a later date, but nobody wants toescalate a situation in the presenceof police.The good news is that we haveno reason to believe that Saberi wasphysically abused (unlike photojournalistZahra Kazemi, who was arrestedand beaten to death in 2003), andSecretary of State Hillary Clintontook up her cause. The bad news isthat Iran didn’t recognize Saberi’sAmerican passport, so it dealt withher as an Iranian, which could havebeen a dead end. Prominent bloggerHossein Derakhshan—often referredto as Iran’s “Blogfather”—has beendetained since November after visitingIsrael using his Canadian passport. Hefaces a potential death penalty. [SeeMohamed Abdel Dayem’s article aboutIranian bloggers on page 42.]Another blogger, Omidreza Mirsayafi,died in Evin Prison in Marchat the age of 29. While the list ofpeople imprisoned, work ceased, andlives ended is long—and most remainanonymous to those of us in the West—Derakhshan and Saberi’s cases are highprofile because of connections they haveto the Western countries and media.In a not-so-subtle political move,President Ahmadinejad has taken theexceptional step of asking authoritiesto reconsider their cases.Of course, being a journalist inIran has always been a challenge. Theformer shah also required journaliststo have government-<strong>issue</strong>d permits inorder to work. Licenses were revoked,and journalists were imprisoned forpublishing stories that were deemedunfavorable to the crown. Yes, thingswere bad even then.In “Journalism in Iran: From Missionto Profession,” Hossein Shahidichronicles the extent to which theSAVAK, the shah’s intelligence organization,controlled the press, crackeddown on dissent, and how that levelof censorship affected the relationshipbetween the public and the press.“There was such deep distrust in theIranian press in the last decade ofthe shah’s rule,” wrote Shahidi, “thatit was often said that the only truthin the papers was to be found in theirdeath notices.”While most Iranian journalists haveto operate with extreme caution, foreignjournalists can be more frank onthe <strong>issue</strong>s they face in Iran. ABC NewsSenior Foreign Affairs CorrespondentMartha Raddatz, for example, wrotea piece for abcnews.com on tanglingwith Iranian authorities in September.[Raddatz’s words appear on page 34.]But then, Iran seldom arrests foreignjournalists. Once in a while an Iranian,such as Azadeh Moaveni, getsaway with the unthinkable—writingfreely outside Iran and returning tothe country without getting a privateride straight to Evin Prison.Of Moaveni’s return to Iran, theauthor and reporter writes in “Honeymoonin Tehran: Two Years of Loveand Danger in Iran”: “My ulteriormotive was to discover whether Icould return at all. In the two yearsthat had passed since my last visit,I had published a book about Iranthat was, effectively, a portrait of howthe mullahs had tyrannized Iraniansociety and given rise to a generationof rebellious young people desperatefor change.”Moaveni was lucky, it seems, butthat she is free is in a way as disconcertingas Saberi’s imprisonment:Both outcomes seem uncomfortablyarbitrary. The uncertainty here is designedto produce alarm, trepidationand silence.But what is behind the high-profilearrests of semiforeign reporters? Bothincidents are seen only as examples ofIran’s unjust, brutal regime. And that16 <strong>Nieman</strong> Reports | Summer 2009

Treatment of Journalistsmight well be all there is to them. Andyet—why would Iran complicate thingsjust as President Obama’s administrationis making what appears to be agenuine attempt to build a diplomaticrelationship? Some speculate thatforces in Iran that are aligned againstcreating any relationship with theUnited States are involved with theserecent arrests. Despite the denial ofIranian officials, is it possible thatSaberi was being held in exchange forthe five Iranian diplomats the UnitedStates has detained in Iraq for overtwo years? Or was locking her upyet another show of strength to theinternational community?There’s also a real sense of justifiedparanoia present in Iran. The UnitedStates has a long, embarrassing historyof meddling in internal Iranian affairs,and The New Yorker’s Seymour Hershhas reported on the clandestine U.S.military operations being carried outin Iran as well as the activities of CIAoperatives working there.In the absence of having a liberated,thriving press—one that can not onlyshine a bright light on the facts but canoperate freely and transparently—we’releft with the necessity of having to tryto understand, rather than decide tojust dismiss, the actions of a governmentthat deals its most severe blowsto its own people. D. Parvaz, a 2009 <strong>Nieman</strong> Fellow,was a columnist and editorial writerat the Seattle Post-Intelligencer untilthe paper stopped its print publicationin March.‘We Know Where You Live’Working for a Western magazine in Iran, a journalist finds that he has acquiredsome surprisingly close acquaintances—from the ministry of intelligence. Andstrangely, they are all called Mr. Mohammadi.BY MAZIAR BAHARIMaziar Bahari is an Iranian journalistand filmmaker who continues to workin Iran. This article first appeared inIndex on Censorship and was subsequentlypublished in the New Statesmanin November 2007.I’m not supposed to tell you this,but I met Mr. Mohammadi. Infact, I met three Mr. Mohammadisin four days. Mohammadi isthe nickname of choice for the agentsof Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence—thecountry’s equivalent of the CIA. Theyhave other nicknames as well, most ofwhich are variations on the names ofShi’ah imams such as Alavi, Hassaniand Hosseini. I guess the names don’tindicate a rank or anything (I haveto guess, because Mr. Mohammadidoesn’t tell you much. He asks thequestions).Mr. Mohammadi is responsible forthe security of Iran. That includesprotecting the values of its government.It’s a tough job. It’s like beingin charge of Britney Spears’s publicimage. The values change so oftenthat the officials who put former colleagueson trial today are careful notto be incarcerated by the same peopletomorrow (who may well have jailedthem in the past). Mr. Mohammadi’sjob is to keep the integrity of theregime intact and to stop those whoplan to undermine the holy system ofthe Islamic Republic.But what does undermining mean?And what if it is the government thatis doing the undermining (as it doesconstantly)? These questions seemto puzzle Mr. Mohammadi. So he ismore than a little paranoid and edgythese days. When he calls you forquestioning, you don’t know if he’sgoing to charge you with somethingor seek your advice.These days, Mr. Mohammadi’smain concern is that the Americanfifth column, disguised as civil rightsactivists, scholars and journalists, isdestabilizing the Islamic Republic.The U.S. government has, after all,allocated $75 million to promote“democracy” in Iran. It is also giving$63 billion in military aid to SaudiArabia, Egypt and Israel to “counterIran.” The United States would love tohave agents in the country to take themoney and spend it wisely. There are somany social and economic problems inIran, that if someone wanted to exploitthem to create dissent it wouldn’t bedifficult to do so. But most activists Iknow inside Iran wouldn’t touch themoney with a bargepole and resentthe American government much morethan their own. In the meantime, theIranian government tries to find foreignperpetrators and domestic accomplicesinstead of solving the root causes ofdissent, such as mismanagement of thecountry’s economy, poverty, internalmigration, and drug addiction.Hotels, Beverages andConversationIn the 1980’s and 1990’s, intelligenceagents were rough and scary, butnowadays they politely call you fortea at some fancy hotel or other toquestion you. I never understood theirfascination with hotels. Why can’t you<strong>Nieman</strong> Reports | Summer 2009 17

Iranjust meet them in their offices? Orwhy don’t they come to your office?Anyway, when you enter the hotelroom you are offered a range of nonalcoholicdrinks. Mr. Mohammadi isvery generous with his beverages. Assoon as you finish your tea you areoffered Nescafé, then some kind ofjuice, then Fanta, Pepsi, etc. Buthe never offers anything solid.Why can you drink tea whilebeing asked about plots againstthe government but not have abiscuit? Does an interrogationover a kebab lunch make it lesstrustworthy?These questions pop intoyour head while you’re enjoyingthe comfort of not beingin Mr. Mohammadi’s presence.He has killed many people inthe past. And you know thathe is capable of violence againif he thinks it necessary. Mr.Mohammadi’s counterparts inthe numerous parallel securityapparatuses (intelligence units of thejudiciary, Revolutionary Guard, andthe police) still have not caught upwith his methods. Recently a numberof students and labor activists were arrested,and instead of being offered teaor Nescafé they spent days in solitaryconfinement and were beaten withelectric cables and batons. But Mr.Mohammadi’s Ministry of Intelligenceis supposed to be the main agency.It is certainly the most professionaland polite.I met the three different Mr. Mohammadiswhile on assignment forNewsweek magazine. I was writingan article about the suppression ofcivil society and civil rights activistsin Iran.Day One: I’ve set up an appointmentwith a teachers’ union leader at a café.I am supposed to meet him after anexam at the high school where heteaches. The teacher doesn’t show upon time. I wait for an hour. Even byIranian standards he is late. I call himon his mobile but it is off. Strange. Hewas so keen to talk the day before, sowhat has happened? I then get a callfrom his mobile.“Who is that?” the caller asks. It isnot the teacher.“I’m Bahari from Newsweek.”“News what?”“Week.”“So you’re a journalist. Will calllater.”Mr. Mohammadi is now targetingmy integrity as a journalist, explicitlytrying to make a connection betweenme and a dissident, suggesting thatwe both work as agents of the GreatSatan and that we are part of a biggerplot to topple the Islamic government.I learn that the teacher was arrestedduring the exam and sent to prison. Anhour later I get a call from a “privatenumber.” It is a new voice. He is muchmore pleasant. “Could you come to the… Hotel at three this afternoon?” asksMr. Mohammadi. It’s been a whilesince I’ve been summoned. NaturallyI oblige.Mr. Mohammadi has become morepolite, cordial and strangely reassuring.He sneaks a smile when I ask him,“Why am I summoned here?” He usedto give me an angry look that wouldmean he was the one in charge. Hebegins by asking simple questionsabout me and my work: Who am I?How long have I worked for Newsweek?Why did I want to meet the teacher?Have I ever met him before? What isthe angle of my story?Easy questions to answer. Mr. Mohammadiis quite relaxed. He scribblesin his notebook while I talk and everynow and then exchanges a smile withme. There’s nothing remotely amusingabout what I’m saying, but Mr. Mohammadikeeps smiling. That makesme think: What is so interesting aboutthe banality I’m spewing here? Is hereally taking notes, or is he doodlinga fish? Is it a dead fish? When is hegoing to let me out of here? Is hegoing to let me out of here?I get tired of talking after a while.Then, like Muhammad Ali in the seventhround of his fight with GeorgeForeman, Mr. Mohammadi snaps andstarts to challenge me. He keepson smiling. I wish he wouldn’t.Why do I think an Americanpublication is interested in talkingto Iranian dissidents? WasI given a list of questions byAmerican paymasters to ask thedissidents? Have I ever been toany conferences in the UnitedStates or Europe? Have I evermet any dissidents in Europeor the United States? How didI come to be chosen as Newsweek’scorrespondent in Iranand not someone else?Mr. Mohammadi is nowtargeting my integrity as ajournalist, explicitly trying tomake a connection between me anda dissident, suggesting that we bothwork as agents of the Great Satan andthat we are part of a bigger plot totopple the Islamic government.Halfhearted InterrogationIf this session had been with previousMr. Mohammadis a few years ago, Iwould be scared of a pending trialand imprisonment for something Ihad never done—a destiny that befellmany of my friends and colleagues.But what makes this Mr. Mohammaditolerable is his halfhearted approachto the whole thing. His expression isnot a grin or a smirk. He almost feelssorry for himself and asks for yoursympathy. He looks genuinely confusedand somehow out of his depth.His bosses have come up with aconspiracy theory and asked Mr. Mohammadito validate it. He is a smartman and has been down this roadmany times since the 1979 IslamicRevolution. It’s never worked in thepast, and he really doesn’t think it willwork now. Mr. Mohammadi knowsthat he’s wasting his time and mine.18 <strong>Nieman</strong> Reports | Summer 2009

Treatment of JournalistsHe knows that his government shouldreform itself if it wants to survive. Asthe former minister of intelligence,Ali Yunesi (who was removed fromoffice by the current president) putit the other day, “Transforming theopposition into our supporters shouldbe the main security strategy of thegovernment, but unfortunately thesedays we not only fail to do that, butchange our supporters into the opposition.”But a job is a job. And Mr. Mohammadihas to pay rent and put food onhis family’s table. He wraps up oursession with a few farewell sentencesthat all other Mohammadis use: “Ihope you don’t think it’s personal.There are people who want to takeadvantage of your good intentions.We just want to protect you.”And then he delivers the punch line:“We know where you live.”Day Two: I’m meeting a labor unionactivist. I’ve set up an appointmentwith him for 3 p.m. I’m supposedto see him after he’s found out thenature of the charges against him inan upcoming trial at the RevolutionaryCourt’s headquarters. The activistis late for our appointment. I try tocontact him, with no success. I calla friend of his: The activist has beenarrested.When I get home, a friend calls mefrom London and says that I’ve beenaccused of being an intelligence agent.Earlier this year, I made a film for theBBC about the MEK, an Iranian terroristgroup that opposes the Islamicgovernment. The film exposed thegroup’s cult-like aspects and its collaborationwith Saddam Hussein andthe Americans. In the film, we alsoshowed how the Iranian Ministry ofIntelligence deals with MEK prisonersrelatively humanely—not torturing orkilling them as they did in the 1980’s,but treating them as cult membersrather than terrorists. This progressiveapproach is converting former MEKmembers into supporters of the government.As a result, the MEK nowaccuses me of being an agent of themullahs. I should tell this story to Mr.Mohammadi if he calls me again.Day Three: Another Mr. Mohammadicalls: “The … Hotel at 11 a.m.” Mr.Mohammadi likes my MEK storybut wonders what the reasons werebehind making the film. “When youmake a film or write an article you doit because you think it’s an importantstory. I really don’t need ulterior motivesfor doing my job, sir.” He doesn’tlook convinced.“But …” and he goes on askingme the same questions as Day One’sMr. Mohammadi. And he smiles thesmile as I start answering him. I givethe same answers: “There is nothingsurreptitious about what I do, sir.I’m just a journalist doing my job. Ijust report what I see around me. Ifthere’s poverty, I report that. If thereare terrorists, I write about them. Andnow when you arrest all these people,wouldn’t it be strange if I didn’t talkabout them? Don’t you find it bizarrethat the MEK calls me an agent inyour pay and you question me as ifI’m a guerrilla fighter?”Mr. Mohammadi says that he issorry for the trouble. He then givesme a modified farewell spiel. Theconclusion remains the same: “Weknow where you live.”Day Four: I’ve been meeting feministactivists to find out why 15 of themwere sent to jail and how they weretreated in Tehran’s Evin Prison. Apparentlytheir Mr. Mohammadi was notthat different from mine. He smiledand tried to find a connection betweenthem and the U.S. government. Lessthan an hour after I leave the houseof my last interviewee, I am invited totea at a hotel. This time it’s different,more upscale. Finally, Mr. Mohammadi’ssmile is gone. “There is onething that you forget in your maturegovernment theory.” I feel that he isfinally coming out of his bureaucraticshell. “I’ve heard that you’ve studiedin Canada.”“Yes.”“Good. Now imagine if Iran has250,000 soldiers in Canada and Mexico(roughly the number of U.S. soldiersin Iraq and Afghanistan) and thenallocates a budget to help civil rightsmovements in the U.S., let’s say to theBlack Panthers or a Native Americanmovement, wouldn’t Americans beparanoid? We know our problemsmuch better than anyone, and we doour best to tell those who are responsibleabout the social maladies you justtalked about. But this is Iran. It takesages for anything to happen. In themeantime we have a vicious enemy todeal with: the U.S. It’s determined totopple our government by any meansnecessary. As Tom Clancy says, the U.S.is: ‘A Clear and Present Danger.’”The Islamic Regime ChangeI don’t know how Mr. Mohammadiwill react to my writing about theseencounters. Not too happily, I guess. Hestrongly advised me not to talk aboutthem with anyone. But it’s importantto know that Mr. Mohammadi haschanged. And if he can change, theIslamic regime can change.I’m still not convinced by his pointabout the American threat. Throughoutits history, the Islamic Republic haslooked for foreign enemies and hasusually found them in abundance.Yet on many occasions it has underminedits own legitimacy by linkinggenuine domestic opposition to itsforeign enemies. It’s time for the internationalcommunity, especially theUnited States, to accept that the IslamicRepublic is a force to be reckonedwith and deserves as much respectas any other sovereign nation. But itis equally important for the IslamicRepublic to realize its own maturityand act responsibly.Maybe instead of a conference on themyth of the Holocaust, our presidentcould organize a conference entitled“Islamic Republic of Iran: 28 Years ofTrials and Tribulations.”On a more personal note, the changecan start with the government treatingits citizens with respect. I know Mr.Mohammadi knows where I live. Hedoesn’t have to brag about it. <strong>Nieman</strong> Reports | Summer 2009 19

IranAN ESSAY IN WORDS AND PHOTOGRAPHSA Visual Witness to Iran’s RevolutionBY REZAIRAN, 1980A demonstration marking the firstanniversary of the revolution.In the mid-1960’s, Reza Deghati taught himselfthe principles of photography as a 14 yearold living in Tabriz, Iran. During the early1970’s, his pictures were of rural society andarchitecture, which he then studied at the<strong>University</strong> of Tehran. The Islamic Revolutionin 1979 shifted Reza’s focus to the city, wherehe covered the conflict for Agence France-Presseand Sipa Press. Reza, who uses only his firstname, then photographed events in Iran forNewsweek until 1981, when he fled Iran afterbeing forced into exile. In the nearly 30 yearssince then, Reza has traveled throughout theMiddle East and Asia, and into Africa andEurope, and had his work published primarilyin National Geographic. “I have been using mycamera as a tool to bear witness,” he writes. InAfghanistan, Reza founded a nonprofit organization,Aina, through which he has supportedthe development of independent media andfostered cultural expression. In 2008, NationalGeographic’s Focal Point published “Reza War+ Peace: A Photographer’s Journey,” and Rezahas generously contributed photographs he tookin Iran in 1979 and 1980 to our project. Hiswords accompany the photos that follow. 20 <strong>Nieman</strong> Reports | Summer 2009

Treatment of JournalistsIRAN, 1979Reza photographed the first massive demonstrationagainst the shah, and in his book he describes howhe came to be there with his camera.My life was turned upside down one fall day in 1978. Iwas working as an architect in Tehran at the time andwas in the architect’s office. Suddenly, I heard a strange,unfamiliar shout. Some angry protestors were screaming,“Marg bar shah!” (“Death to the shah!”). I went towatch from the window. Soldiers came and blocked thestreet from both sides.The soldiers shot blindly into the crowd. The studentscould do nothing. Some died instantly, falling to theground. Others, wounded, crawled away to protect themselves.Still others ran for shelter. Then I saw one studentwho was fleeing but taking pictures as he ran.I stayed by the window for three hours, transfixed by thechaos below and in a complete state of shock. I made adecision. That night, I gave up my job. I turned in mykeys to the architect’s office, and I took up my cameras,which I haven’t put down since. Instability ruled in Iran;unrest and demonstrations were occurring everywhere.At event after event, I met Don McCullin, Marc Riboud,Olivier Rebbot, and Michel Setboun, among many otherphotojournalists who had come to Iran from all over theworld. They showed me the ropes. After a few months,my photographs started appearing in the internationalpress.I became a correspondent for Sipa Press and for Newsweek.I covered the revolution, the riots, the war againstIraq, the war against the Kurds. Iran was boiling. Theutopian fervor of the revolution had soon given way torepression. The shah had been brought down, but themullahs who took power crushed every form of opposition,every difference of opinion. The first victims werethe former political prisoners who had fought againstthe shah. This carnage led me to a sad observation:Hasn’t history shown us that every revolution eats itsown young?In February 1981, I was wounded on the Iran-Iraq frontby a shell blast. The Iranian government was closingdown the borders. My wound served as a pretext for meto leave the country. I went overseas for medical treatment.A few days before I left, I had learned that I was awanted man, sentenced to death because of my photographs.My journey outside my country would be along one.Photo and text by Reza.<strong>Nieman</strong> Reports | Summer 2009 21

IranFABRIC STORE, IRAN, 1979For months, I had watched the black chadors takeover, becoming more and more widespread in thetowns and the countryside. Yet Iran has a variety ofpeople, a multiplicity of colors and landscapes. Eventhough decades have passed since I last saw them, Ican still recall the rural women with their colorful petticoats,which contrasted with the red of their houses,made of clay. And I can still see the vividly coloredrugs and the fabrics with the elaborately workedembroidery.When I entered this fabric shop, where the only choicelay in the weave of the material, I felt stifled anddepressed. The only style available was for the chador;the only color offered was black.During those days, I often felt that, unconsciously, thepeople of Iran had agreed to go into mourning.Photo and text by Reza.22 <strong>Nieman</strong> Reports | Summer 2009

Treatment of JournalistsIRAN, KURDISTAN, 1980Reza met an 11-year-old boy named Peyman in Kurdistan, whose fatherhad been killed and, as they spoke, Peyman said to him, “Whatelse is there to say about my life, about our fate as a people whoare refused an identity? What about you? You say you know a littleabout us through your camera lens. You say you will tell the worldabout us. But I have a hard time understanding how you will do this.Come, I will introduce you to my grandfather.”Reza went to his house, where they had tea. As he writes, “I thoughtabout the Kurdish children I had come across, their eyes full of sadness.Peyman was watching me attentively but seemed distracted. Heappeared weighed down, as though he were dozens of years older.Despite their grief, his family welcomed me. After we finished tea,I left the sad warmth of their home. As I reached the corner of thestreet, I heard a violent blast. Then there was silence, then screams,the despair and horror of a mother whose children have just beentorn from her. I turned around. In the dust of the dirt and rockspulverized by the bomb’s impact, I saw some motionless bodies.”Peyman, his sister and his grandfather had just been murdered—bombed by the Revolutionary Guards.Photo by Reza.<strong>Nieman</strong> Reports | Summer 2009 23

IranIRAN, 1980, AYATOLLAH KHOMEINIAt last, I had the opportunity to photograph Ayatollah Khomeini in anintimate, private setting. This would be my chance to try to gain someunderstanding of this man who had become such a powerful enigma.He was sitting in a bare room, which had no past or future, no historyor memory. I had time to take only three photos. Then he cut me off,saying harshly, “I’m tired.” Throughout our session, he never looked mein the eye. I had sought his gaze to silence a doubt that had lurked in mesince his return to Iran a year earlier. When he arrived, a reporter hadasked him what he felt about being back after 15 years of exile. His reply,“Nothing.”He was the symbol of hope for an entire nation. We had risen up againstthe shah in a revolution that had erupted spontaneously throughoutthe country. But after my brief encounter with Khomeini, the doubt Ifelt gave way to the certainty that a fist was about to come down on ourdreams of justice and freedom.Photo and text by Reza.A year after I took this photo, I left Iran, forced into exile. Earlier I hadbeen arrested by the shah’s secret police for being a dissident. I wasimprisoned for three years and tortured for five months. Now, becauseof my photographs showing the repression carried out by Khomeini’sregime, I was under threat from his government and had to flee. In theyears since then, I have been a nomad searching for a part of my homelandin every country I visit—a quest that is like picking up and reassemblingthe scattered pieces of a puzzle. My camera is always looking forthe truth that often hides in the shadows of events.24 <strong>Nieman</strong> Reports | Summer 2009

Treatment of JournalistsIRAN, KURDISTAN, 1980Kurdish house bombarded by Iranian Revolutionary Guards.CEMETERY, IRAN, 1981In writing about his journey to becoming a photographer inIran and his departure from his country, Reza observes that“Iran had become a huge cemetery, where figures dressed inblack wandered among the tombs.” Photos by Reza.<strong>Nieman</strong> Reports | Summer 2009 25

IranFilm in Iran: The Magazine and the Movies‘… there are two arenas—cinema and soccer—that while not completelyimpervious to the political torrents have a greater margin of immunity.’BY HOUSHANG GOLMAKANISome imagine Iran as a desert withblack mounds, caravans of camels,men with harems, and oil wells.They might be surprised to learn thatin this country we have three dailiesand two weeklies about cinema andmore than 10 film monthly magazines,almanacs, quarterly periodicals, onequarterly in English about Iraniancinema, and dozens of books on thesubject published each year.Why is so much written about film?Perhaps because each year more than100 feature-length films and 2,000short films and documentaries aremade in Iran. Hundreds of TV showsand films are produced for 10 staterunbroadcast channels. (Iran doesnot have private radio and TV.) Hundredsof students attend four publicfilm colleges, and more private filmacademies are scattered throughoutIran. A government-owned firm andprivate companies also make filmsfor release in shops and video clubs.What’s written gets consumed by manyviewers of international films, whichshow up quickly for black market saleon city sidewalks.Reporting on political matters is arisky business. Journalists have grownaccustomed to the shutting down ofpublications, having to move and startnew ones. Under such circumstances,there are two arenas—cinema andsoccer—that, while not completelyimpervious to the political torrents,have a greater margin of immunity.Film—The MagazineThe first film publication in Iran waspublished in 1930. By the time of theIslamic Revolution in 1979, there wereabout 30 publications, the majority ofwhich had very short life spans. Duringthe early years of the revolution—whenAccompanying Golmakani’s words are covers of Film.politics pervaded everything—theproduction and showing of films wasstill unorganized, there were no filmpublications, and the Iranian pressrarely paid attention to cinema.In 1981, a few friends and I decidedto start a monthly film magazine; byJune 1982, our first <strong>issue</strong> of Film waspublished with reviews of some of thebetter films being released in hundredsof video clubs in Iran. By choosing tofeature film criticism—with the approachof critiquing the better filmsand excluding the weaker ones—Filmhas deeply influenced filmmakers, governmentofficials overseeing cinema,and created a more serious generationof viewers. Many young Iranian filmmakerstell us that theylearned about cinemafrom reading Film duringtheir childhood andadolescence. At leastit can be claimed thatduring the years of war,political upheaval, socialdespair, and dearthof film showings, Filmkept love for cinemaalive.Now 27 years old,Film is Iran’s longestlastingpublicationabout cinema. Throughthe years we’ve increasedthe number ofpages, and since 1986we have published seasonalspecial editions,including “Iranian FilmYearbook,” added in1991. Two years later,we were publishing aquarterly periodical inEnglish.As happens everywhere,the biggest quarrelsthat happen with the film industryare about criticism—Film twice facedboycotts by Iran’s Film ProducersUnion. But this is not the only problem.In the 1980’s, when Film was Iran’sonly magazine about cinema, officialsin charge of cinema were opposed tothe stardom of popular actors. Theyfelt directors and screenwriters shouldbe the stars, which is contrary to thegeneral nature of cinema and the tasteof cinemagoers who identify with filmsthrough their actors. Yet, in Iran, filmpublications, until midway throughthe 1990’s, had to be cautious aboutframing <strong>issue</strong>s relating to actors.In these same years, restrictions onthe showing of foreign films meant26 <strong>Nieman</strong> Reports | Summer 2009

Treatment of Journaliststhat discussion in our pages aboutthem was also restricted. Rarely wasa picture of a foreign film or actorshown on the cover of any filmpublication. Even though in the past10 years we’ve seen an astonishingincrease in foreign films shown onIranian public TV—the majority ofwhich are American—those who writeabout them still risk being accusedof “promoting the Western culture”for giving attention to them. Early in2003, five film critics were arrestedon this charge and were imprisonedfor one to four months.To be sure, this type of strict enforcementis not a general governmentpolicy. Rather it is the result of themultiplicity of views and actions ofgovernment bodies that at times havenothing to do with cultural matters.Film, by maintaining its emphasis oncultivating artistic taste, has continuedalong the path it carved without comingunder the influence of extremistor very conservative sentiments. Accordingto the Iranian saying, it hastaken a “slow and steady” walk. Thisaccounts for Film still publishing,while hundreds of publications haveopened and been shut down duringits lifetime.Film critique is widely read anddesired by Iranians. In the past 20years, with an increase in film publicationsand the steady presence offilm sections in the public press, thenumber of film critics has risen noticeably.They now have formed anassociation, and the 27-year-old FajrFilm Festival in February is the mostimportant film event in Iran. In itsearly years, film critics would have fitin one row of seats; now at the festivalthere is one theater with three auditoriumsfor film critics, writers andreporters. The question and answersessions after each film showing isso much in demand that sometimesa seat cannot be found.It’s a love and hate relationshipbetween film critics and the filmindustry. Ads about films are verylimited in the press; in many of Film’s<strong>issue</strong>s we have not one page of filmadvertisement. And to preserve Film’sindependence, most of its ads comefrom noncinema sources. The relationshipwe have with the government, asan official supervisory apparatus, isthat of principal to student. Like thepress in Iran, making of film in Iranenjoys a minimum level of subsidy; thedegree of support within a budget canvary depending on the adherence ofthe film’s subject to state politics.I write about all of this only outof my experiences with Film, wherewriting about cinema has given mylife meaning. Along the way, I’ve discoveredmany companions and beenconnected with many more unseenfriends. Sometimes I receive touchingletters from readers, old and new, whoseletters tell of their attachment to Filmin such a way that reading their wordsbrings tears to my eyes. At 55, thesmell of ink and newsprint from each<strong>issue</strong> that arrives from the printinghouse still overwhelms me, even thoughI’ve already read every word and knowthe details of its production. Flippingthe pages of each new <strong>issue</strong> is stillso pleasurable that I am unwillingto trade my job for any other in theworld, even if it might be easier orhigher paid. Houshang Golmakani is the founderand chief editor of Film, a monthlymagazine that has been published inIran for the past 27 years. InternationalFilm, a quarterly magazinepublished by Film Publications, canbe read in English at www.film-international.com.<strong>Nieman</strong> Reports | Summer 2009 27