Lessons learned from the EBIPM large- scale cheatgrass control and

Lessons learned from the EBIPM large- scale cheatgrass control and

Lessons learned from the EBIPM large- scale cheatgrass control and

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

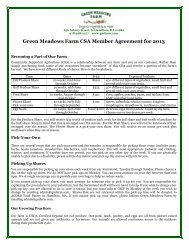

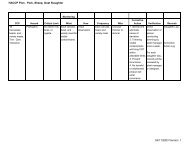

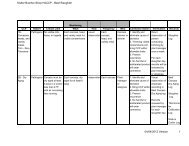

Need Financial Assistance to Improve yourL<strong>and</strong> or Operation?By Jeff Schick, NRCS District ConservationistThe Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) has aprogram that may be able to help you. The EnvironmentalQuality Incentives Program (EQIP) is a voluntary programthat provides financial assistance to improve your operationin ways that will also provide environmental benefits.The benefits of this program will improve <strong>and</strong> enhanceBox Elder County’s soil health, water quality <strong>and</strong> quantity,air quality, <strong>and</strong> wildlife habitat <strong>and</strong> increase <strong>the</strong> ability ofproducers to maintain a sustainable agriculture operation.Over <strong>the</strong> past ten years, many of <strong>the</strong> county’s producershave already participated in this program. Almost $17 milliondollars have been utilized to improve Box Elder’s naturalresources <strong>and</strong> make local agriculture, dairies, livestockproducers, farms, orchards, <strong>and</strong> ranches more sustainable.If you want to improve your operation, <strong>large</strong> or small, youcan apply for this program here at <strong>the</strong> USDA ServiceCenter in Tremonton at any time. There are batching periodsduring each year when funding selections are made<strong>and</strong> projects are selected to be funded for <strong>the</strong> year.When you apply, <strong>the</strong> staff here will use <strong>the</strong>ir expertise tohelp you to analyze your operation <strong>and</strong> develop a plan tohelp you to:increase crop yields,make range <strong>and</strong> pastures produce better <strong>and</strong>more forage,build soil instead of deplete it,manage animal waste to meet current regulations,conserve water by applying it more effectively<strong>and</strong> efficiently,extend vegetable harvest season, <strong>and</strong>improve your operation in many o<strong>the</strong>r ways.It is our objective to endeavor to make your operationmore sustainable for you <strong>and</strong> your family <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> generationsto follow. Please come into <strong>the</strong> office <strong>and</strong> visit withus.<strong>Lessons</strong> <strong>learned</strong> <strong>from</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>EBIPM</strong> <strong>large</strong><strong>scale</strong><strong>cheatgrass</strong> <strong>control</strong> <strong>and</strong> revegetationproject in Park Valley, UtahBy Justin Williams, Rangel<strong>and</strong> Management Specialist,USDA-ARS Forage <strong>and</strong> Range Research Laboratory,Logan, Utah & Tom Monaco, Research Ecologist, USDA-ARS Forage <strong>and</strong> Range Research Laboratory, Logan,UtahAdopting <strong>the</strong> <strong>EBIPM</strong> FrameworkEfforts to <strong>control</strong> invasive weeds often fail to achieve lastingresults if <strong>the</strong>y do not impact <strong>the</strong> underlying causes ofweed dominance <strong>and</strong> invasion. For this reason, <strong>the</strong> USDA-Agricultural Research Service has teamed up with universities<strong>and</strong> l<strong>and</strong> management agencies in <strong>the</strong> western U.S.to develop <strong>and</strong> demonstrate how <strong>the</strong> adoption ofEcologically Based Invasive Plant Management (see www.<strong>EBIPM</strong>.org), can lead to systematic l<strong>and</strong> improvements.Adopting <strong>EBIPM</strong> can help producers maximize productivity<strong>and</strong> improve economic viability in five simple steps(see table below). Here, we briefly describe <strong>the</strong> outcomeof adopting <strong>the</strong> <strong>EBIPM</strong> Framework in Park Valley, Utah.Management GoalWe’ve all seen it, thous<strong>and</strong>s of acres of rangel<strong>and</strong>s in BoxElder County infested with <strong>cheatgrass</strong>. Although thisannual grass may be productive in early spring, it is not areliable source of forage in low precipitation years. Thepromise of something better, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> fear of letting aninvasive annual grass take over rangel<strong>and</strong>s, has promptedrenewed interest in ways to successfully <strong>and</strong> economicallyconvert grazed l<strong>and</strong>s to perennial grass pastures (Figure1). When successful, this conversion is a win-win for both<strong>the</strong> ecosystem <strong>and</strong> producers. For example, producers willenjoy a more stable <strong>and</strong> reliable forage base than thatprovided by <strong>cheatgrass</strong>, while our shared ecosystem willbe left in better shape than it was found. Our goal in ParkValley was simple – increase forage production, reducewildfire frequency, <strong>and</strong> better underst<strong>and</strong> how to similarlyconvert <strong>cheatgrass</strong> pastures to perennial grass pasturesin <strong>the</strong> future.Project ImplementationIn 2008-2009, we completed <strong>EBIPM</strong> Steps 1 <strong>and</strong> 2 <strong>and</strong>determined that <strong>cheatgrass</strong> dominance across <strong>large</strong>-<strong>scale</strong>study pastures was due to abundant dry litter production,frequent wildfire disturbance, hyper-abundance of <strong>cheatgrass</strong>seed on <strong>the</strong> soil surface, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> absence of desirableplant species to compete with <strong>cheatgrass</strong>. Consulting<strong>the</strong> available list of <strong>EBIPM</strong> principles in Step 3 to guide ourmanagement decisions, we reasoned that disturbancemust be modified, even if only temporarily, to reduce<strong>cheatgrass</strong> litter <strong>and</strong> seeds <strong>and</strong> to allow seeded perennialcontinued on page 6...4Conservation Connection

...continued <strong>from</strong> pg. 4 'Cheatgrass Control'grasses to gain a foothold. Thus, in <strong>EBIPM</strong>Step 4, with <strong>the</strong> cooperation <strong>and</strong> insightsof producers, we determined that fire<strong>and</strong> herbicide application could be usedstrategically to reduce <strong>cheatgrass</strong> litter<strong>and</strong> seed production <strong>and</strong> improve soilsurface conditions prior to seeding desirableperennial grasses. In essence, thismanagement strategy was deemedappropriate because it was capable ofsimultaneously altering site conditions,plant species availability, <strong>and</strong> plant speciesperformance.In Fall 2009, replicated pastures ownedby two different producers in Park Valley,Utah were assigned to one of four treatmentcombinations – untreated, burnedonly(early November), herbicide application-only(mid-November, Plateau®applied at <strong>the</strong> rate of 40oz/acre), <strong>and</strong>burned+herbicide application. In earlyDecember, all pastures were drill-seededwith a seed mix that consisted of bothnative <strong>and</strong> introduced perennial grasses(total = 9 lbs of seed/acre). The averagecost for applying <strong>the</strong>se treatments was asfollows: fire, $30/acre; herbicide, $40/acre; <strong>and</strong> seeding, $30 acre. It is importantto note that <strong>the</strong>se costs reflect professionalcontracts, which are expectedto be much lower if a producer is capableof applying <strong>the</strong>ir own <strong>cheatgrass</strong> <strong>control</strong><strong>and</strong> revegetation treatments.Initial OutcomesTwo years after treatment (2011), burning<strong>and</strong> herbicide, especially when combined,effectively reduced soil surface litter<strong>and</strong> <strong>cheatgrass</strong> seed on <strong>the</strong> soil surface.In <strong>the</strong> same token, perennial grassestablishment was significantly greater inall treatments when compared tountreated pastures. For example, fireonlyresulted in over three perennialseeded plants per square yard, whileherbicide-only resulted in just over twoseeded plants per square yard. In contrast,when fire <strong>and</strong> herbicide were combined,<strong>the</strong>re averaged five seeded plantsper square yard. A particularly promisingaspect of <strong>the</strong>se results is that perennialThe Five <strong>EBIPM</strong> Steps1. Complete Rangel<strong>and</strong> HealthAssessment with an USDA-NRCS specialist.2. Identify causes of weed invasion<strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> associated processesin need of modification.3. Use ecological principles toguide decision making.4. Choose appropriate tools<strong>and</strong> strategies based on ecologicalprinciples.5. Design <strong>and</strong> execute a planusing adaptive management.Figure 1. Management goal ofproject in Park Valley, Utah includedreducing wildfire threat <strong>and</strong> improvingforage production in dry years.grasses successfully established eventhough <strong>cheatgrass</strong> within pasturesincreased due to higher-than-averageprecipitation in both 2010 <strong>and</strong> 2011.However, livestock grazing in 2012 willhopefully reduce <strong>the</strong> threat of wildfireoccurrence during what appears to be aseason of considerable wildfire risk,given drought conditions <strong>and</strong> high litterproduction during both 2010 <strong>and</strong> 2011.<strong>Lessons</strong> Learned <strong>and</strong> FutureOpportunitiesUsing <strong>the</strong> <strong>EBIPM</strong> framework helpeddefine <strong>the</strong> underlying causes of <strong>cheatgrass</strong>dominance <strong>and</strong> guided <strong>the</strong> implementationof an ecologically appropriatemanagement strategy. We are encouragedby <strong>the</strong> results of this pasture-levelstudy <strong>and</strong> hope that it inspires additionalproducers to adopt <strong>the</strong> <strong>EBIPM</strong> frameworkwhen choosing to convert <strong>cheatgrass</strong>pastures to perennial grass pastures.A few points warrant considerationwhen adopting this ecologically basedapproach. First, although <strong>cheatgrass</strong> willlikely continue to be a pest into <strong>the</strong>future, pastures invaded by this grasswill not “right-<strong>the</strong>mselves” over timewithout active interventions to trigger<strong>the</strong> desired conversion. Second, itappears that perennial grass establishmentis essential for pasture sustainability<strong>and</strong> to prevent re-invasion by <strong>cheatgrass</strong>.Finally, pasture conversion is aprocess that likely requires more thanthree years <strong>and</strong> depends on whe<strong>the</strong>r<strong>cheatgrass</strong> is effectively impacted bytreatments <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> initial establishmentof perennial grasses. During this conversionperiod, we advocate <strong>the</strong> use ofadaptive management approaches asoutlined in Step 5 of <strong>the</strong> <strong>EBIPM</strong> frameworkto fur<strong>the</strong>r help producers protect<strong>the</strong>ir investments in weed <strong>control</strong> <strong>and</strong>revegetation <strong>and</strong> realize economic gainsthat are anticipated due to improved forageproduction. In this vein, it may benecessary to carefully consider futuregrazing practices that will weaken <strong>cheatgrass</strong>while streng<strong>the</strong>ning <strong>the</strong> spread<strong>and</strong> performance of perennial grasses.6Conservation Connection