The Global Financial Centres Index - 1 - Z/Yen

The Global Financial Centres Index - 1 - Z/Yen

The Global Financial Centres Index - 1 - Z/Yen

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

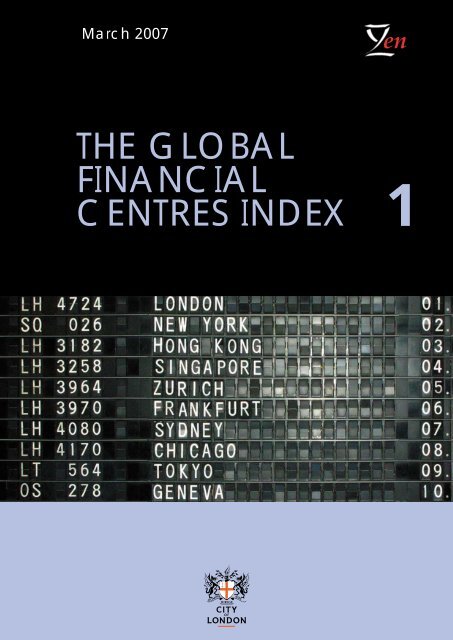

March 2007enTHE GLOBALFINANCIALCENTRES INDEX1

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong> is published by the City ofLondon. <strong>The</strong> authors of the report are Michael Mainelli andMark Yeandle of Z/<strong>Yen</strong> Group Limited.This report is intended as a basis for discussion only. Whilstevery effort has been made to ensure the accuracy andcompleteness of the material in this report, the authors, Z/<strong>Yen</strong>Group Limited, and the City of London, give no warranty inthat regard and accept no liability for any loss or damageincurred through the use of, or reliance upon, this report orthe information contained herein.March 2007© City of LondonPO Box 270, GuildhallLondonEC2P 2EJwww.cityoflondon.gov.uk/economicresearch

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong><strong>Financial</strong><strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>March 2007ContentsForeword 31. Executive Summary 82. Background 103. <strong>The</strong> GFCI 124. Analysis of <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> 185. Instrumental Factors 245a. People Factors 255b. Business Environment Factors 295c. Market Access Factors 355d. Infrastructure Factors 395e. General Competitiveness Factors 436. Overview of Survey Results 477. Conclusion 508. Appendices 52Appendix A. Methodology 52Appendix B. <strong>The</strong> Online Surveys 56Appendix C. <strong>The</strong> Instrumental Factors 58Bibliography 63

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>2

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>ForewordMichael SnyderChairman, Policy and Resources Committee, City of LondonIn a globalised and interdependent world economy thedynamics of international competitiveness have becomeincreasingly important for domestic policy makers. Cities thatare financial centres face greater competitive forces thanmost, for the financial services industry is at the heart of theglobal economy, acting as the facilitator of world trade andinvestment. Those of us charged with the delivery of effectivepublic policy need to understand the complex ingredientsof success to ensure that our financial centres remain globallycompetitive. Moreover, we need to know how theworld’s financial centres rank relative to each other on anongoing basis.This research, by Z/<strong>Yen</strong> Ltd, is the first to report on a newbiannual index of competitiveness for 46 world financialcentres. <strong>The</strong> first <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong> (GFCI)presented here ranks London and New York as the leadingcentres, followed by Hong Kong, Singapore and Zurich.London has a narrow lead over New York, but the twotogether are significantly ahead of the rest of the field to bethe only true global financial centres. Overtime the GFCI willbecome a more powerful tool as we expand the number ofcentres and we further develop the <strong>Index</strong> to allow increasingsophistication in analysing changes in the relative strengthsof financial centres.I welcome the GFCI findings, which clearly identifyLondon’s global strengths relative to its major competitors.London’s prime position is a reflection of the unrivalledtalent pool clustered here; our firm but fair principles-based3

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>regulation supported by good market access; and anexcellent business environment.<strong>The</strong>re is no doubt, however, that the real merit of the GFCI isthe identification of changing priorities and concerns. Whenwe published our report <strong>The</strong> Competitive Position of Londonas a <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> Centre back in November 2005, theavailability of skilled personnel was regarded as the mostimportant factor of competitiveness. Almost 18 months on, itis regulatory and tax issues that have come to be seen as thebiggest contributors to overall competitiveness. <strong>The</strong> latter is aparticular concern for London, as anxieties about thecorporate tax regime relative to our major competitors arewidespread among respondents.<strong>The</strong> GFCI will prove to be an invaluable tool for trackingchanging fortunes and perceptions of financial centres,and I encourage industry professionals to participate in ourongoing survey.Michael SnyderLondonMarch 20074

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>5

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>Chart 1<strong>The</strong> GFCI WorldVancouverSan FranciscoChicagoMontrealTorontoNew YorkWashington DCHamiltonCayman Islands6

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>StockholmHelsinkiEdinburghOsloCopenhagenDublinAmsterdamLondonBrussels WarsawFrankfurtChannelPragueParis LuxembourgIslands Zurich BudapestGeneva ViennaMilanRomeLisbon MadridAthensMoscowBeijingSeoulShanghaiTokyoDubaiMumbaiHong KongSingaporeSydneyMelbourneWellington7

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>1. Executive Summary<strong>The</strong> City of London Corporation’s <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>(GFCI) evaluates the competitiveness of 46 financial centresworldwide. It is updated regularly to identify changes in financialcentre competitiveness.<strong>The</strong> GFCI currently shows that London and New York are the two leadingfinancial centres globally, with London ahead of New York by 5 ratingpoints. London and New York are well ahead of the two strongest Asiancentres of Hong Kong and Singapore which occupy 3rd and 4th placesrespectively. It is interesting to observe that Zurich, a financial centrestrongly focused on the two niche sectors of private banking and assetmanagement, is in 5th place just ahead of Frankfurt in 6th place.It is worthwhile noting that London leads New York in all five areas ofcompetitiveness, i.e. people, business environment, market access,infrastructure and general competitiveness. It is also notable that inthe most recent of the two online surveys, London is further ahead ofNew York than it was in the previous study. In November 2005 the gapbetween the two cities was very small. Taking the city assessmentsfrom the most recent study in isolation, London is ahead of New Yorkby 37 points.In the 2005 study, there was no clear leader amongst the Asian centres.It is now clear that Hong Kong (3rd in the GFCI) leads the way fromSingapore (4th). <strong>The</strong>se two financial centres are well ahead of Tokyo(9th), and the two Chinese centres of Shanghai (24th) and Beijing (36th).Paris is now just outside the top ten in 11th place, only three pointsbehind Geneva. Toronto is in 12th position, perhaps higher than onemight expect. Toronto, however, is the national financial centre ofCanada and acts as a major international centre. Toronto is rated withinthe top ten on people and business environment factors and Canada isvery highly placed on the general competitiveness instrumental factorsused in the GFCI model. Two US cities follow Toronto: San Francisco andBoston are in 13th and 14th place respectively and are strong regionalcentres which benefit from the sheer size of the US economy.<strong>The</strong> research involved in producing the GFCI has revealed a change inemphasis of the areas of competitiveness. In 2005, people and skillsissues were rated as the most important factors of competitivenessfollowed by regulatory issues. In this research, people factors have beenreplaced as the most important factor by the regulatory and taxenvironments. Concerns about the level and quality of regulation in theUSA and about the increasing levels of corporate taxation in the UK arewidespread amongst our respondents. GFCI ratings will change asinstrumental factors and financial centre assessments change. Weintend to publish results twice a year.8

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>Table 1<strong>The</strong> Top 10<strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong>ComparedLondon 1 765 Most key success areas are excellent – London is in the topquartile in over 80% of its instrumental factors. Especially strongon people, market access and regulation. <strong>The</strong> main negativecomments concern corporate tax rates, transportinfrastructure and operational costs.New York 2 760 Most areas are very strong – New York is also in the top quartilein over 80% of its instrumental factors. People and marketaccess are particular strengths. Our respondents citedregulation (particularly Sarbanes-Oxley) as the main negativefactor.Hong Kong 3 684 Hong Kong is a thriving regional centre. It performs well in allof the key competitiveness areas, especially in regulation.Headline costs are high but this does not detract from overallcompetitiveness. Hong Kong is a real contender to become agenuinely global financial centre.Singapore 4 660 Most areas are very good and banking regulation is oftencited as being excellent. It performs well in four of the keycompetitiveness areas but falls to 9th place on generalcompetitiveness factors alone. Definitely the second Asiancentre just behind Hong Kong.Zurich 5 656 A very strong niche centre. Private banking and assetmanagement provide a focus. Zurich performs well in three ofthe key competitiveness areas but loses out slightly in peoplefactors and in general competitiveness.Frankfurt 6 647 Despite a strong banking focus, suffers from inflexible labourlaws and skilled staff shortages. Market access, infrastructureand business environment are strong but Frankfurt falls outsidethe top ten GFCI rankings for people and generalcompetitiveness.Sydney 7 639 A strong national centre with good regulation, offering aparticularly good quality of life. Sydney is strong in four of thekey competitiveness areas but falls outside the top ten forpeople – many financial professionals leave for larger Englishspeakingcentres.Chicago 8 636 Number two centre in the US. Hampered by the sameregulatory regime as New York. It scores highly for people butis let down by its infrastructure and market access rankings.Unlikely to overtake New York, it remains a powerful regionaland specialist centre.Tokyo 9 632 Does not fare well in terms of regulation and businessenvironment, but the size of the Japanese economy meansTokyo has good liquidity. It fares poorly on people but hasgood infrastructure and market access.Geneva 10 628 A strong niche centre similar to Zurich. Private banking andasset management continue to thrive. Geneva is strong inbusiness environment and general competitiveness but letdown by infrastructure.<strong>The</strong> theoretical maximum GFCI rating is 1,000Please participate in the GFCI by rating the financial centres youare familiar with at: www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/GFCI9

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>2. Background<strong>The</strong> City of London Corporation regularly commissions research oncompetitiveness. Two pieces of research in 2003 1 and 2005 2evaluated London’s competitiveness as a financial centrecompared to New York, Paris and Frankfurt. Both reports showedthat London and New York are the two key global financialcentres while there are many other international, specialist(niche), national and regional financial centres.<strong>The</strong> GFCI is designed to extend the City of London Corporation’sresearch by providing an ongoing ranking system for a muchwider range of financial centres, starting with 46 instead of theprevious four. <strong>The</strong> advantages of an index over the previousstudies are:■ the wider range of cities permits analysis of financial subsectors,e.g. insurance or banking, and not just “finance”because a greater number of assessments allow for statisticallyvalid comparisons;■ shorter, and more direct, questionnaires leads to moreauthoritative comparisons by asking senior figures to rate justthe cities with which they are familiar;■ use of a wide range of instrumental factors (initially 47) enablesbetter analysis of the factors of competitiveness;■ the continuous nature of an index provides more frequent andmore timely information than a snapshot survey, as well as easycomparisons over time.<strong>Financial</strong> services is an attractive business sector for cities seekingto develop because it has been a successful, high growth, sectorfor the past quarter of a century, and because it is a highly mobilesector, which can be directly influenced by policy and planning.For this reason, the competitiveness of financial centres is of greatrelevance to government officials and regulators as can be seenin this excerpt from a HM Treasury Report:<strong>Global</strong>isation creates new competitive pressures forLondon’s financial sector. <strong>The</strong> integration of theglobal economy means that easily replicable‘commoditised’ jobs will tend to shift to the lowestcost locations in emerging markets. In thisenvironment, the challenge for London is to ensurethat it remains the world’s most attractive andcompetitive environment from which to providesophisticated and high value-added financialservices to the rest of the world. 3Previous research has indicated that there are many factors ofcompetitiveness. We group these into five key areas. <strong>The</strong> first four1 Centre for the Study of<strong>Financial</strong> Innovation,Sizing up the City –London’s Ranking as a<strong>Financial</strong> Centre,Corporation of London(June 2003).2 Z/<strong>Yen</strong> Limited, <strong>The</strong>Competitive Position ofLondon as a <strong>Global</strong><strong>Financial</strong> Centre,Corporation of London(November 2005).3 HM Treasury, <strong>Financial</strong>Services in London:<strong>Global</strong> Opportunitiesand Challenges, (March2006).10

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>of these are: People; the Business Environment; Market Accessand Infrastructure. When a financial centre is strong in these fourareas this creates a critical mass which we term GeneralCompetitiveness.Each of the key indicators covers several aspects ofcompetitiveness:■ People considers the availability of good personnel, the flexibilityof the labour market, business education and the developmentof ‘human capital’. Previous research highlighted this factor asthe single most important factor in financial centrecompetitiveness;■ Business Environment looks at regulation and also tax rates,levels of corruption, economic freedom and the ease of doingbusiness. Regulation, a major component of the businessenvironment, is currently cited as a decisive factor in thecompetitiveness of London and New York. Our online surveyposes a question about the most important competitive factorsfor financial centres and regulation was mentioned by more ofour survey respondents than any other factor. Too onerous aregulatory environment can directly affect the competitivenessof a financial centre. A recent report by McKinsey & Companyargues that Sarbanes-Oxley has had a detrimental effect onNew York’s competitiveness. 4 London is considered heavilyregulated but overall the regulatory environment is morecompetitive than in New York, although there is increasingconcern on the tax front;■ Market Access examines the levels of securitisation, volume andvalue of trading in equities and bonds as well as the clusteringeffect of having many firms involved in the financial servicessector together in one centre;■ Infrastructure is mainly concerned with the cost and availabilityof buildings and office space, although we are seeking reliableindicators to broaden its scope;■ General Competitiveness, the concept that the whole is‘greater than the sum of the parts’ considers overallcompetitiveness levels of cities and how cities are perceived asplaces to live.4 McKinsey & Co.,Sustaining New York’sand the US’ <strong>Global</strong><strong>Financial</strong> ServicesLeadership, (January2007).11

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>3. <strong>The</strong> GFCI<strong>The</strong> GFCI provides ratings for financial centres calculated by a‘factor assessment model’ built using two distinct sets of input:■ instrumental factors – drawn from external sources. For example,infrastructure competitiveness for a financial centre is indicatedby ‘instrumental factors’ including a cost of property survey andan occupancy costs index; a fair and just business environmentis indicated by ratings such as a corruption perception indexand an opacity index. Objective evidence of competitivefactors has been sought in instrumental factors drawn from awide variety of comparative sources – 47 instrumental factorswere used to construct this first set of GFCI ratings. <strong>The</strong>se include,for example, Mercer’s Quality of Living Survey, UBS’s WageComparison <strong>Index</strong>, Transparency International’s CorruptionPerceptions <strong>Index</strong>, and Anholt’s City Brands <strong>Index</strong>. Not allcentres have data for all instrumental factors and the statisticalmodel takes account of these gaps;■ financial centre assessments – to construct the first set of GFCIratings we used 491 responses to two online surveys (detailed inSection 6 of this report). Each respondent assessed the financialcentres they knew. We received 3,992 individual financialcentre assessments. <strong>The</strong> second online survey is runningcontinuously to keep the GFCI up-to-date with people’schanging assessments.<strong>Financial</strong> centres are assessed in terms of five key competitivenessareas: people, business environment, market access, infrastructureand general competitiveness.At the outset of this project, a number of guidelines were set out toensure that financial centre assessments and instrumental factorswere selected and used in a reliable and consistent manner. Forexample, indices used as instrumental factors should, whereverpossible, be readily available, regularly updated, provided by areputable body and derived using a sound methodology.<strong>The</strong> financial centre assessments and instrumental factors werecombined using statistical techniques to build a predictive modelof financial centre competitiveness using support vector machinemathematics. <strong>The</strong> predictive model was used to answer questionssuch as “If an investment banker gives Singapore a certainassessment, then, based on the instrumental factors for Singaporeand Paris, how would that person assess Paris?” This predictivemodel produced competitiveness ratings for 46 financial centres.Full details of the methodology behind the GFCI can be found inAppendix A. <strong>The</strong> results are shown in Table 2:12

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>Table 2<strong>The</strong> GFCI<strong>Financial</strong> CentreRatings<strong>Financial</strong> Centre Rank RatingLondon 1 765New York 2 760Hong Kong 3 684Singapore 4 660Zurich 5 656Frankfurt 6 647Sydney 7 639Chicago 8 636Tokyo 9 632Geneva 10 628Paris 11 625Toronto 12 611San Francisco 13 611Boston 14 609Edinburgh 15 605Cayman Islands 16 604Hamilton (Bermuda) 17 603Melbourne 18 603Channel Islands 19 600Washington D.C. 20 594Montreal 21 580Dublin 22 579Amsterdam 23 577Shanghai 24 576Dubai 25 570Luxembourg 26 570Vancouver 27 558Madrid 28 558Stockholm 29 558Milan 30 546Brussels 31 540Helsinki 32 537Oslo 33 529Copenhagen 34 525Vienna 35 518Beijing 36 513Wellington 37 508Rome 38 474Mumbai 39 460Warsaw 40 460Prague 41 453Lisbon 42 453Seoul 43 434Budapest 44 425Moscow 45 421Athens 46 39513

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>Successful financial centres fulfil one or more of five different roles:■ <strong>Global</strong> financial centres – there are two cities that can claim tofulfil this role, London and New York;■ International financial centres such as Hong Kong that conducta significant volume of cross-border transactions;■ Niche financial centres that are worldwide leaders in one sector,for example Zurich in private banking;■ National financial centres that act as the main centre forfinancial services within one country. Toronto, for example, is thenational financial centre of Canada;■ Regional financial centres that conduct a large proportion ofregional business within one country. Chicago, as well as beingan international centre is also a regional one.<strong>The</strong> GFCI emphasises a point made in other studies, London andNew York are the two leading financial centres. In the GFCI, thetwo top-rated cities, London (765) and New York (760), are fivepoints apart on a scale of 1,000. <strong>The</strong> third highest-rated city is HongKong (684), 76 points lower. <strong>The</strong> next largest gap is betweenWellington (508) at 37th place and Rome (474) at 38th place, a 34point difference. London and New York are distinct – these areglobal financial centres.International activity involves, at its simplest, at least two locationsin different jurisdictions. <strong>Global</strong> deals increase the number ofinvolved parties markedly, e.g. lawyers, accountants, exchangesand analysts. While a direct foreign exchange deal between aretail bank in Korea and a Tokyo investment bank is international,the addition of a third party, e.g. backing with a credit derivative,is likely to make the deal global. <strong>Global</strong> financial centres comeinto their own when there are two or more parties or a need fordeep liquidity.Several centres score highly on the basis of being strong in oneparticular niche of financial services, e.g. Zurich for private bankingor Hamilton for reinsurance. While these niche financial centres willalmost certainly never rival London or New York as global financialcentres, they are as strong as London or New York within their ownsector.A national financial centre conducts a significant proportion of aparticular country’s financial business. Where there are multiplefinancial centres in a country, e.g. Canada, Australia and the USA,the situation is complicated. In Canada, for instance, the GFCIcovers Toronto (ranked 12th), Montreal (ranked 21st) andVancouver (ranked 27th). All three are sizeable financial centres,but Toronto is the national centre. In countries where there are14

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>multiple financial centres, the national centre is frequently tied withforeign exchange connections.A regional financial centre is one that conducts most of its businesswithin one region of one country. In addition to its role as aninternational financial centre, Chicago is a regional financialcentre for the American Midwest.A few examples of the roles that financial centres can play areshown in Table 3.Table 3<strong>The</strong> DifferentRoles of <strong>Financial</strong><strong>Centres</strong>Centre <strong>Global</strong> International Niche National RegionalLondon ■ ■ ■ ■ ■Hong Kong ■ ■Chicago ■ ■ ■Hamilton ■ ■Sydney ■ ■ ■<strong>The</strong> GFCI helps our understanding of the complexity ofinternational financial arrangements. In the 1970’s and 1980’s,studies assumed that financial centres developed following a“hub-and-spoke” or “central-regional-store-distribution” retailmodel. Much of the literature of the 1980’s assumed that Tokyowould become an international centre because of its largedomestic economy. International finance was assumed to growout of domestic finance. Nowadays, international finance hasbecome so complex that this assumption may not be valid.In contrast to earlier studies in the 1980’s and 1990’s, the domesticmarkets affiliated with London and New York did not come up as adominant factor in the GFCI. <strong>The</strong> US economy is at least five timesthat of Britain’s, yet London and New York are roughly level ininternational finance.London or New York often connect regional participants directly,without using national or regional financial centres as hubs. AKorean mortgage bank may well be working on regional financialdeals and be located in Seoul, but the bank’s internationaldealings could be direct with counter-parties in London or NewYork, not via a sub-hub or international expert in Seoul.<strong>The</strong>re has been considerable speculation as to whetherShanghai, Hong Kong, Tokyo or Singapore will emerge as aglobal centre. It may be that no single Asian centre emerges as15

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>a third global centre and that the liquidity generated by thegrowth of the main Asian economies is split between two ormore centres. Shanghai was the most commented-upon Asiancity in the 2005 City of London study but, with the GFCI askingrespondents to compare a number of Asian financial centres,now Hong Kong is clearly 3rd and Singapore 4th to London andNew York. Current thinking seems to be that Shanghai andTokyo are unlikely to become truly global centres. Hong Kongseems the most likely Asian city to emerge – it has a strongregulatory system and a well skilled financial services workforce.Singapore is a close second behind Hong Kong.Recent research on complexity and networks at the Santa FeInstitute 5 and elsewhere has been contrasting the growth ofcities with biological growth. While this research is at an earlystage, there is clear evidence emerging of the importance of‘laws of scale’:■ decreasing returns to scale, such as vulnerability to thespread of disease or over-density preventing distribution, doexist for cities. Decreasing returns to scale hold cities backfrom growing too large;■ increasing, but diminishing, returns to scale, such as masstransportation, permit cities to be more efficient but ‘tail off’above a certain point.<strong>The</strong>re are, however, examples of increasing, and accelerating,returns to scale. Examples of increasing, and accelerating,returns to scale include a number of network effects such astelephone usage or internet connections. <strong>The</strong> Santa Fe Institutehas found some early evidence of increasing returns to scale incity inventiveness and creativity.Cities are networks, and financial centres are located in cities.Increasing returns to scale come from obvious sources amongthe GFCI’s key success areas. People improve their skills andmarketability by making connections, which is easier in cities.<strong>The</strong> Business Environment improves where trust is high and thecosts of oversight are reduced. In cities, more firms can be seen,compared and evaluated in less time. Market Access benefitsare clear. It is good to be where your customers are, andcustomers gain from being able to make purchase selectionsrapidly. Infrastructure in cities is more efficient.Telecommunications, education and health services are allmore easily delivered where people are concentrated.General Competitiveness shows that a financial centre needsto be good at most things to be a leading centre – successbreeds success and clustering is of vital importance. <strong>The</strong> five5 Pumain, Denise, ScalingLaws and Urban Systems,Santa Fe InstituteWorking Paper – 04-02-002, (August 2003).16

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>key success factors are discussed in more detail later inthis report.Each respondent to the online surveys only assessed the cities withwhich they were familiar. In order to build the GFCI, the factorassessment model made predictions of how each respondentwould assess the cities they did not know, based on theassessments they gave to cities that they knew.<strong>The</strong> top financial centres, such as London and New York, havelower sensitivity to instrumental factors and narrower variances intheir assessments than other cities, therefore their future GFCIratings are likely to be fairly stable. Other centres, such asWellington and Helsinki, though poorly ranked today, have greatsensitivity to instrumental factors and a wide variance inassessments, thus they may change position significantly.Whether it is pride of ‘ownership’ or ‘regret avoidance’, it is clearthat residents give better city assessments for their home cities thannon-residents do. If we exclude residents’ assessments of their owncities, then on average the score for all cities is 3.4% lower. Somecities, such as Frankfurt and Hong Kong, are significantly boostedby ‘home town’ support while the more ‘international’ centresseem to have a more stable ranking. For example:■ Frankfurt – Non-resident predictions are 7.4% lower thanassessments made by residents;■ Hong Kong – Non-resident predictions are 11.1% lower;■ London – Non-resident predictions are 2.8% lower;■ New York – Non-resident predictions are 2.2% lower;■ Paris – Non-resident predictions are 2.2% lower.Some of the home bias might be explained by specialisation.<strong>Financial</strong> cities other than London or New York are either strong in asector or have a strong domestic market that they represent. Forexample, Hamilton is strong in certain insurance sectors and Zurichis strong in asset management and private banking. Some of thehome bias might be explained by nationalism or a local view of astrong economy meeting international finance. Frankfurt, Sydneyand Paris all represent strong domestic markets on theinternational stage.17

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>4. Analysis of <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong>Participants seem to choose to place their transactions and theirbusiness based on multiple criteria, so any taxonomic approachhas difficulties. It is a combination of factors that makes a financialcentre successful, not just a single factor.<strong>The</strong> GFCI shows that you need to be good at most things to be aleading centre. London and New York are in top quartile of over80% of the instrumental factors in which they feature. Looking atLondon specifically, it is in the top quartile in 36 out of the 43instrumental factors. So far, where London is weak, for exampleoperating costs, these factors can be seen as problems of success.Commercial and domestic property prices are high and rising inLondon because demand exceeds supply. If people did not wantto locate in London, property prices would fall. It should beremembered that property costs are only one element of overalloperational cost and the commercial property prices in Londonare not currently hindering competitiveness in financial services.In order to explore the GFCI ratings, we examined the correlationof each instrumental factor with the GFCI rating. <strong>The</strong> R2 values (awidely used measure of correlation) were calculated and the tenmost closely correlated instrumental factors are shown in Table 4:Table 4InstrumentalFactorCorrelationwith GFCIInstrumental FactorR2 with GFCI<strong>Financial</strong> Markets <strong>Index</strong> 0.583European Cities Monitor 0.541Capital Access <strong>Index</strong> 0.484<strong>Global</strong> Competitiveness <strong>Index</strong> 0.469World Competitiveness Scoreboard 0.427Price Comparison <strong>Index</strong> 0.405Ease of Doing Business <strong>Index</strong> 0.404Happiness Scores 0.404Opacity <strong>Index</strong> 0.400Nation Brands <strong>Index</strong> 0.384Further analysis of instrumental factor correlation with the GFCIshows that R2 in excess of 80% is achieved using two variables – forexample, the <strong>Financial</strong> Markets <strong>Index</strong> and the <strong>Global</strong>Competitiveness <strong>Index</strong>, both fairly broad measures ofcompetitiveness (for European cities, the European Cities Monitoralso provides very strong correlation with GFCI when modelledwith the <strong>Financial</strong> Markets <strong>Index</strong>). Similarly, R2 results of 90% areachieved using three variables – the <strong>Financial</strong> Markets <strong>Index</strong>, the<strong>Global</strong> Competitiveness Scoreboard and the Nation Brands <strong>Index</strong>.18

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>We examined how stable the rankings might be in the future. Inorder to do this we needed to contrast the overall ranking withits sensitivity to changes in instrumental factors. Our approachwas to remove one of the five groups of key success factors, andthen re-rank the cities. We looked at how much removing agroup of factors changed city rankings. We then looked at thevariance among the five new scores, which we termed“sensitivity”. If a city’s ranking changed markedly by removingany of the five groups of factors, we anticipated that it had a lotof potential to improve, or decline. If a city’s ranking remainedstable despite removal of each of the groups of factors, we feltthat the city was more likely to remain near its current position.Chart 2 is an overall diagram that contrasts GFCI ratings withincreasing sensitivity.Chart 2<strong>The</strong> 46 <strong>Centres</strong> –GFCI Ratingversus Sensitivityto InstrumentalFactors<strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong> Rating >LeadersLondon• • New York•Hong Kong•Singapore•Zurich•Frankfurt•SydneyChicago•Geneva••Paris• •San Francisco Tokyo•Boston •Hamilton Edinburgh •Toronto•• • Melbourne•Channel IslandsWashington DC•Cayman Islands •Dublin•Montreal•Luxembourg •Amsterdam•Vancouver•Madrid•Milan•Brussels •Helsinki•Beijing•StockholmEvolving•Shanghai•Dubai•Oslo•Copenhagen ••Wellington Vienna•MumbaiMinor•Seoul•Rome•Prague•Warsaw•Lisbon•Bucharest•Moscow•AthensVolatileSensitivity to Instrumental Factors >19

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>We believe that this categorisation identifies four types offinancial centre:■ Leaders: obviously London and New York, but also centres withstrong sub-sectors and strong domestic markets;■ Minor: cities that are not rated as highly, and are unlikely toimprove in the near term. It is interesting to note that Rome,Moscow, Mumbai, Seoul and Warsaw fall into this category.Each of these centres have large domestic markets, but seemunlikely to change their poor ratings soon;■ Volatile: cities that are not rated as highly, but might be able tomove upwards rapidly if they could fix some factors.Interestingly, Athens has gained from improvements ininfrastructure due to the 2004 Olympic development, but needssimilar improvements in the other four groups of factors toimprove its competitive position;■ Evolving: cities with high ratings, but susceptible to change. It isinteresting to see that Dubai and Shanghai are alreadymatching established centres such as the Channel Islands andHamilton. Dubai has clearly focused on attracting regionalbusiness, while Shanghai has been the focal point for itsdomestic business. As their financial services broaden anddeepen, we expect these two centres to move towards the“leaders” box.Perhaps the most interesting field is in the centre where cities suchas Madrid, Dublin and Amsterdam compete to become moreattractive to the financial services industry. Canada has threecities all vying here – Toronto, Vancouver and Montreal. Likewise,three Scandinavian cities rival each other – Stockholm,Copenhagen and Oslo. It is tempting to speculate that only a fewof these can move forward. As regulatory conflicts and responsessettle down, however, we expect to see an increasing amount ofbalancing between “quality and cost”.We also looked at the ‘spread’ or variance of the individualassessments given to each city. This variance is plotted against theGFCI rating in Chart 3.20

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>Chart 3<strong>The</strong> 46 <strong>Centres</strong> –GFCI Ratingversus Varianceof Assessments<strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong> >London••New York•Frankfurt•Paris•Hong Kong••SingaporeZurich•Sydney• •Tokyo• ChicagoGenevaBoston• •San Francisco Montreal Hamilton•Melbourne •Edinburgh•••Channel•Washington DCIslands•Amsterdam •Dublin •Dubai•Cayman Islands •Luxembourg••PragueShanghai•Madrid•Toronto •Stockholm•Vancouver•Milan•Brussels•Helsinki•Copenhagen •Oslo•Beijing•Vienna•Wellington•Rome•Mumbai•Lisbon•Warsaw•Seoul•Bucharest•Moscow•AthensIncreasing Variance of Assessments >This chart shows that certain centres tend to receive a far broaderrange of assessments than others. On the far right are centres suchas Hamilton, Montreal, Shanghai, Vancouver and the ChannelIslands. <strong>The</strong> assessments given to these centres had a significantlyhigher variance (i.e. some respondents assessed them highly andother respondents assessed them poorly). <strong>The</strong>se centres have themost to gain or lose in future GFCI ratings. <strong>The</strong> centres on the far leftof the chart received far more consistent assessments. In the caseof London and New York, these assessments were consistentlyhigh. In the case of centres such as Frankfurt, Paris, Zurich, HongKong and Singapore, assessments were fairly consistent but lowerthan for London and New York.In Chart 4 we have contrasted the sensitivity and variance ofassessments:21

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>Chart 4<strong>The</strong> 46 <strong>Centres</strong> –Variance ofAssessmentsversus Sensitivityto InstrumentalFactorsIncreasing Sensitivity to Instrumental Factors >•Dublin•Montreal•Amsterdam•Madrid•Vienna•Copenhagen•Dubai•Warsaw•Athens•Bucharest•StockholmMoscow• •Lisbon•Beijing•Prague •Rome•Toronto•Helsinki•Montreal•Oslo•Wellington•Shanghai•Chicago•Milan•Dublin•Seoul•Zurich•Tokyo•Mumbai• Brussels•Melbourne•Hong Kong•Luxembourg•LondonNew York•Cayman Islands•San Francisco•SydneyEdinburgh• •Singapore•Washington DC•Paris•Geneva •Boston•Frankfurt•Vancouver•Hamilton•ChannelIslandsIncreasing Variance of Assessments >Chart 4 shows three distinct ‘bands’ of financial centres. <strong>The</strong>centres in the top right of the chart, such as Copenhagen, Oslo,Vienna, Wellington, Shanghai or Dubai, have a high sensitivity tochanges in the instrumental factors and a high variance ofassessments. <strong>The</strong>se centres undoubtedly have the highestpotential volatility in GFCI ratings.<strong>The</strong> centres in the bottom left of the chart (including London, NewYork, Paris, Frankfurt, Hong Kong, Singapore, Zurich and Geneva)have a low sensitivity to changes in the instrumental factors and alower variance of assessments. <strong>The</strong>se centres are likely to exhibitthe lowest volatility in future GFCI ratings.<strong>The</strong> GFCI permits sectoral analysis and, over time, we hope tocreate ‘mini-indices’ by business sector i.e. banking, assetmanagement, insurance, professional services and regulatory.While sectoral analysis at this early stage would be premature,Chart 5 contrasts the first GFCI ratings derived from banking sectorrespondents against GFCI ratings derived from non-banking sectorrespondents.22

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>Chart 5<strong>The</strong> Top 10<strong>Financial</strong><strong>Centres</strong> –BankingRespondentsversusNon-BankingRespondents<strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong> >800750700650600550500LondonNewYorkHongKongSingaporeZurichFrankfurtSydneyChicagoTokyoGenevaGFCI Banking Sector OnlyGFCI Non-Banking SectorsCity >Chart 5 is an initial indication of how a sectoral split of the GFCImight look. Based on the relatively small sample, it can be seenthat financial centres are seen more favourably by people notinvolved in banking. This might indicate that bankers operate in amore global market place and are less concerned with thecompetitiveness of individual financial centres.23

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>5. Instrumental FactorsIn this section we examine the five key areas of financial centrecompetitiveness and how these combine to contribute to thecompetitiveness of centres. <strong>The</strong> GFCI factor assessment modelwas run with one set of factors at a time and the results comparedto identify which factors influence which centres.This approach does identify one issue with the instrumental factorsthat have been used. Instrumental factors are used as proxies forsomething that is not directly measurable. A number of theinstrumental factors we used are based on rankings derived at anational level (i.e. country by country). <strong>The</strong>re are clearly regionalvariations within countries and taking a national ‘average’ is likelyto skew the results. When the GFCI model is used with allinstrumental factors there are sufficient city rankings to give anaccurate reflection but when the model is run only using one set offactors (as in the following sections) some of the ratings are undulyinfluenced by the use of these nationally based factors.24

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>5a. People Factors<strong>The</strong> people factors used in the GFCI (details of these are shown inAppendix C) are:■ Executive MBA <strong>Global</strong> Rankings, <strong>Financial</strong> Times■ European Human Capital <strong>Index</strong>, Lisbon Council■ Human Development <strong>Index</strong>, UNDP■ Labour Productivity, OECD■ Education Expenditure, OECD■ Quality of Living Survey, Mercer HR■ Happiness Scores, NationMaster■ World’s Top Tourism Destination, World Tourism OrganisationChart 6 shows the top ten cities by GFCI rating when only using thepeople related factors in the prediction model.Chart 6<strong>The</strong> Top 10<strong>Financial</strong><strong>Centres</strong> Usingonly PeopleRelatedInstrumentalFactorsCity >LondonNew YorkSan FranciscoChicagoHong KongTorontoSingaporeZurichMontrealBoston500 550 600 650 700 750 800Rating >London and New York occupy 1st and 2nd positions respectivelyon people factors. It is no coincidence that they are consistentlyassessed as having the best people. Several comments from therecent online survey conducted for the GFCI testify to this:What’s important is to make it easy to find the bestemployees from around the world. English speakingcities such as London and New York have a hugeadvantage here.25

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>Frankfurt, which only a few years ago hadambitions to overturn London as Europe’s keyfinancial centre, now has a dearth of talent – a lotof the good banking people now work in London.Interestingly San Francisco rises by nine places to 3rd, Chicago hasmoved up four places and Boston has also risen. This is largelybecause six of the eight people related instrumental factors arenationally based (compiled on a country by country basis ratherthan being based on specific cities). American cities benefit fromsharing the same values in national indices as New York.Toronto and Montreal have also climbed up the rankings.Canadian cities benefit from the fact that they score well in theQuality of Living survey, NationMaster’s Happiness Scores and theHuman Development <strong>Index</strong>.Hong Kong is in 5th place in the GFCI using people factors. It hasdeveloped strong expertise in professional services. <strong>The</strong> number ofChartered <strong>Financial</strong> Analysts, for example, has increased fromabout 200 in 1995 to more than 3,000. Indeed, Hong Kong has the4th largest number of Chartered <strong>Financial</strong> Analysts in the world afterthe US, Canada and the UK. <strong>The</strong> business cluster surrounding thefinancial services industry is well-developed with more than 5,000solicitors and about 1,000 barristers now practising in Hong Kong 6 .Frankfurt and Sydney have fallen just outside the top ten in thislisting, occupying 11th and 12th places, still above most otherregional and national centres.Earlier research ranked the availability of skilled personnel and theflexibility of the labour market as the most important factors in thecompetitiveness of a financial centre. <strong>The</strong> people who add realvalue in financial centres are often flexible about where they workand factors such as the quality of life, culture and language seemto play an increasingly significant part in their location decisions.Mercer HR assess 215 cities in their Quality of Living Surveyeach year. 39 criteria are used and New York is used as abenchmark with a score of 100. Selected scores of interest areshown in Table 5.266 Securities & FuturesCommission Hong Kong,Hong Kong as a Leading<strong>Financial</strong> Centre,(August 2006).

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>Table 5Quality ofLiving <strong>Index</strong> –Selected Scores<strong>Financial</strong> CentreQuality of Living <strong>Index</strong>Zurich 108.2Geneva 108.1Vancouver 107.7Vienna 107.5Frankfurt 107.0Sydney 106.5Wellington 105.8Amsterdam 105.7Brussels 105.6Toronto 105.4Melbourne 105.0Luxembourg 104.8Stockholm 104.7Montreal 104.3Dublin 103.8San Francisco 103.2Helsinki 103.1Oslo 102.8Paris 102.7Singapore 102.5Tokyo 102.3Boston 101.9London 101.2Washington D.C. 100.4Chicago 100.4Madrid 100.1New York 100.0Although London appears well down this list of selected cities, it isabove New York and still within the top quartile of the 215 citiescovered. HM Treasury recently highlighted quality of life as one ofLondon’s competitive advantages. 7 <strong>The</strong> arts contribute to thequality of life in a city and London’s arts festivals and institutionsattracted over 10 million visitors in 2005.NationMaster produces a less broadly-based Happiness <strong>Index</strong>compiled simply by asking the question “Taking all things togetherwould you say that you are: very happy, quite happy, not veryhappy or not at all happy?”. <strong>The</strong> sum of the last two options issubtracted from the sum of the first two options to give a score.Sweden, Denmark and Australia are all within the top five, the UK isin 9th place and the US is in equal 13th place with France. Canadais in 17th place, Japan features in 19th and China in 29th. Whenlooking at these ‘national’ indices, it should of course beremembered that there will be regional variations within countries.7 HM Treasury, op. cit.,(March 2006).27

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>Another instrumental factor used in the GFCI model to assess thepeople factors is the list of top International Tourist Destinationscompiled by the World Tourist Organisation. We used levels oftourism as an instrumental factor for quality of living. This list istopped by France which has a clear lead over Spain, the US andChina. <strong>The</strong> UK is in 6th place, Canada is 12th and Hong Kong 16th.<strong>The</strong> European Human Capital <strong>Index</strong> compiled by the LisbonCouncil, places the UK in 3rd place behind Sweden and Denmarkwith France in 8th place and Germany in 10th. <strong>The</strong> EuropeanHuman Capital <strong>Index</strong> seeks to measure the ability of countries todevelop their human capital through efficient development,deployment and utilisation. <strong>The</strong> UK’s placing backs up the widelyheld perception that the availability of skilled personnel is better inthe UK than in most other European countries.<strong>The</strong> UK fares less well in the Human Development <strong>Index</strong> (HDI) bythe UNDP which puts Australia in 3rd place, followed by Sweden,Canada, Japan and the US in that order. France is in 16th placeand the UK in 18th – still ahead of Germany and many othercountries represented in the GFCI. <strong>The</strong> HDI is a more generalmeasure of development and measures health, standard of livingand knowledge.Specific financial services education is often provided by postgraduatebusiness schools and the list of Executive MBA rankings,compiled by the <strong>Financial</strong> Times is another instrumental factorused in the GFCI model. This overall ranking is based on a detailedassessment of 20 different criteria. It is perhaps no surprise thatmany of the US business schools score very highly. Eight of the topten executive MBAs are from business schools based in the US.London Business School ranks 5th and Insead (headquartered inFrance but with international coverage) ranks 9th. In the UK,business schools attached to Oxford, Cambridge and Manchesteruniversities feature highly in this list as do Cass Business School,Ashridge and Imperial College London. Oxford EconomicForecasting recently highlighted that London benefits from thepresence of a number of world-class universities.Additionally London’s growth has been bolstered by stronginternational immigration – 126,000 people in 2005 (more than halfof the UK total). London benefits from large inflows of professionaland managerial workers. London attracts both skills and talentthrough immigration and allows people to develop those skills inhighly productive activities. In 2005, 32% of London’s workforcepossessed degrees or higher education qualifications (NVQ level 4and 5 or above) 8 , higher than the rest of the UK where thepercentage is 25%.8 Oxford EconomicForecasting, London’sPlace in the UK Economy2006-07, City of London(November 2006).28

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>5b. Business Environment Factors<strong>The</strong> 15 business environment related instrumental factors (details ofthese are shown in Appendix C) used in the GFCI are:■ Administrative and Economic Regulation, OECD■ Business Environment, Economist Intelligence Unit■ Total Tax Rates, World Bank/PwC■ Corporate Tax Rates, OECD■ Employee Effective Tax Rates, PwC■ Wage Comparison <strong>Index</strong>, UBS■ Personal Tax Rates, OECD■ Total Tax Receipts (As a Percentage of GDP), OECD■ Ease of Doing Business <strong>Index</strong>, World Bank■ Opacity <strong>Index</strong>, Kurtzman Group■ Corruption Perceptions <strong>Index</strong>, Transparency International■ <strong>Index</strong> of Economic Freedom, Heritage Foundation■ Economic Freedom of the World <strong>Index</strong>, Fraser Institute■ <strong>Financial</strong> Markets <strong>Index</strong>, Maplecroft■ Political Risk Score, Exclusive AnalysisChart 7 shows the top ten cities by GFCI ranking when only usingthe business environment related factors in the prediction model.Chart 7<strong>The</strong> Top 10<strong>Financial</strong><strong>Centres</strong> Usingonly BusinessEnvironmentRelatedInstrumentalFactorsCity >LondonNew YorkChicagoHong KongSydneySingaporeZurichFrankfurtTorontoMontreal500 550 600 650 700 750 800Rating >29

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>Again, London and New York are placed 1st and 2nd respectively.Previous research has indicated that the regulatory environment,a strong component of what we call the ‘business environment’is one of the most important competitiveness factors for afinancial centre.<strong>The</strong>re is however, a continuing debate in financial services as towhether lighter regulation will actually increase the scale of thebusiness. Both sides of this debate have invoked alternativeversions of Gresham’s Law – “good money drives out bad” and“bad money drives out good”. 9London and New York are seen as having generally goodregulatory environments although currently many people arecritical of the US because of what is seen as a ‘heavy-handed’approach to regulating financial services. One quote from theGFCI online survey is typical of a number of other similar comments:New York is becoming far too rules-based andis getting wrapped in red tape (but not as badas Tokyo).<strong>The</strong>re are two sides to the regulatory environment, the quantity andrigour of the regulations themselves and the way in which firms areexpected to comply. Many finance professionals perceive thatregulators, such as the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC),adopt a prescriptive ‘rules based’ approach whilst the <strong>Financial</strong>Services Authority (FSA) has a less prescriptive ‘principles based’approach.It appears that there are two major aspects of regulation that theUS needs to tackle. Firstly, the SEC is good at enforcing the existingregulations but is less strong at ensuring that the financial marketsrun efficiently. Secondly there are too many regulators, forexample, four separate banking regulators and a clash ofresponsibilities between state and federal regulators.<strong>The</strong>re has been much discussion recently about the effect that theSarbanes-Oxley legislation has had on the US financial centres andespecially on New York. It is claimed that London has benefittedfrom Sarbanes-Oxley with international firms preferring to list inLondon rather than in the US. Figures certainly indicate that agreater proportion of international listings are now being hosted byLondon than has been the case in recent history.It is possible to overstate the detrimental effect of one piece oflegislation and forget other sources of competitive disadvantage.A detailed study into the cost of raising capital in various markets9 Mundell, Robert,Uses and Abuses ofGresham’s Law inthe History of Money,Columbia University,(August 1998).30

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>reported recently that, although significant, the cost of Sarbanes-Oxley compliance was not the biggest cost involved in raisingcapital. 10 <strong>The</strong> biggest cost was the high fees charged by Wall Streetbanks (6.5% to 7% of the value of shares offered against a typicallevel of 3% to 4% in Europe).Of the other leading cities in the GFCI the only other city that hasshown a major change by running the GFCI on businessenvironment factors alone is Chicago. This is because all thebusiness environment instrumental factors are based on nationalscores rather than on individual city scores. Chicago has benefittedfrom having similar values to New York. Toronto and Montreal havejust edged into the top ten, displacing Tokyo and Geneva –Canada does well on many of the regulatory based instrumentalfactors.<strong>The</strong> OECD produces an index of administrative and economicregulation and a selection of the scores is shown in Table 6 (a lowscore indicates more effective regulation).10 Oxera ConsultingLimited, <strong>The</strong> Costof Capital:An InternationalComparison, City ofLondon, (June 2006).Table 6Administrativeand EconomicRegulationCountry Administrative Regulation Economic RegulationUnited Kingdom 0.80 1.40Canada 0.80 1.40Australia 1.00 0.90Norway 1.00 2.30USA 1.10 1.30Denmark 1.10 1.40Ireland 1.10 1.50Sweden 1.10 1.70Finland 1.30 1.90New Zealand 1.40 1.10Portugal 1.50 2.20Luxembourg 1.60 1.50France 1.60 2.30Italy 1.60 2.60Japan 1.70 1.40Austria 1.90 1.50Netherlands 1.90 1.60Germany 1.90 1.80Belgium 1.90 1.80Greece 1.90 2.20Spain 2.00 2.10Switzerland 2.20 2.00Czech Republic 2.40 2.00Poland 2.90 2.7031

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong><strong>The</strong> UK and the US fare well in both of these indices, although onaverage both are behind Australia. Canada, New Zealand andthe Scandinavian countries also perform well. Whilst Hong Kongand Singapore do not feature in this index, several of our surveyrespondents perceive that Hong Kong is above Singapore (andwell ahead of Shanghai) due to more effective regulation.Another instrumental factor used in creating the GFCI is theBusiness Environment ranking compiled by the EconomistIntelligence Unit (this covers nine categories including the politicalenvironment, government policy towards enterprise and foreigninvestment, the foreign trade and tax regime and the taxationstructure of 82 countries). Denmark, Finland and Canada fill thetop three spaces and are followed by Singapore, with the UK in 7thplace, the US in 8th and Hong Kong in 9th.An alternative way of viewing the effect that regulation has on thecompetitiveness of a financial centre is the degree of ‘economicfreedom’ that a particular jurisdiction offers. <strong>The</strong> Fraser Instituteproduces an Economic Freedom indicator which is used in theGFCI model. This contains five components and shows broadlysimilar standings to the Heritage Foundation’s <strong>Index</strong> of EconomicFreedom, with Hong Kong and Singapore at the top and Chinanear the bottom. In this index the US is just ahead of the UK.A further factor for the Business Environment is the World Bank’sEase of Doing Business Indicator. This ranks countries on ten topicsincluding employing people, dealing with licences and otherregulation, paying taxes and enforcing contracts. Singapore topsthis list with the US, Canada, New Zealand, Hong Kong and the UKwithin the top 10 from over 170 countries.<strong>The</strong> GFCI model includes four instrumental factors which give anindication of how ‘fair and just’ a business environment is and howeasy it is for businesses to operate. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Index</strong> of EconomicFreedom, published by the Heritage Foundation, measures tenfactors of economic freedom for over 160 countries. A smallselection of country rankings is shown in Table 7 together withrankings from the Kurtzman Group’s Opacity <strong>Index</strong> and theCorruption Perceptions <strong>Index</strong> published by TransparencyInternational.32

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>Table 7Country Rankingsin three of theBusinessEnvironmentInstrumentalFactorsCountry <strong>Index</strong> of Opacity CorruptionEconomic Freedom <strong>Index</strong> PerceptionsHong Kong 1 5 15Singapore 2 12 5Luxembourg 4 - 13United Kingdom 5 2 11Denmark 8 2 4New Zealand 9 - 2USA 9 6 17Canada 12 8 14Switzerland 15 8 7<strong>The</strong> Netherlands 16 12 11Austria 18 8 10Sweden 19 2 6Germany 19 14 16Japan 27 16 21Norway 30 - 8France 44 26 18China 111 44 78Russia 122 39 126<strong>The</strong> <strong>Index</strong> of Economic Freedom clearly demonstrates one of thereasons why many finance professionals believe that if there is tobe a third global financial centre in Asia, it is likely not to be on theChinese mainland but in Hong Kong or Singapore.A further aspect of the Business Environment is business culture.Although difficult to measure, this culture can be represented bysome instrumental factors. <strong>The</strong> Kurtzman Group attempt tomeasure one aspect of cultural behaviour in their Opacity <strong>Index</strong>.This is calculated from some 65 variables and examines factorssuch as corruption levels, detrimental economic policy andinadequate governance practices. <strong>The</strong> ratings from this index areshown alongside another, similar instrumental factor, the narrowerCorruption Perceptions <strong>Index</strong> published by TransparencyInternational. <strong>The</strong> UK does well in these indices, appearing abovethe USA in all three as shown in Table 7. In the Opacity <strong>Index</strong> the UKis joint 2nd whilst Hong Kong is 5th and New York is 6th.Another facet of the regulatory environment is the tax regime –both for corporate taxes and personal taxes. A number of therespondents to the GFCI survey believe that the UK is beginningto lose competitive advantage in this area. A typical quote fromour survey:<strong>The</strong> UK used to be a good place to be purely fortax reasons but I’m not sure that this is any longerthe case.33

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>Several taxation indices were incorporated into the GFCI modelas instrumental factors. <strong>The</strong> first was an adaptation of DoingBusiness, a survey produced by PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC)for the World Bank. PwC adapted their model to reflect a financialservices firm more accurately than the manufacturing companynorm used in the calculations for the World Bank. <strong>The</strong> model is notjust the ‘headline corporation tax’ rate (although this is also builtinto the GFCI model) but a combination of corporate income tax,social security or other labour taxes and also property andturnover taxes. <strong>The</strong> rates (rounded to the nearest percentagepoint) that apply in some countries are shown in Table 8 togetherwith Effective Employee Tax Rate – again using PwC methodologyand adapting their model to represent, more closely, a financialservices employee.Based on the Total Corporate Tax Rates, London is placedsignificantly ahead of New York, although behind Hong Kong andSingapore which are both well ahead in terms of personal tax rates.London also lags behind three European competitors: Zurich,Geneva and, significantly, Dublin – a city within the European Union.Table 8SelectedCountries –Corporate &Personal TaxRatesCity Total Corporate Tax Rate 2006 Effective Employee Tax Rate 2006Zurich 25% 22%Geneva 25% 28%Dublin 26% 37%Singapore 29% 15%Hong Kong 29% 16%London 35% 34%Warsaw 38% 41%Montreal 43% 39%New York 46% 31%Oslo 46% 38%Amsterdam 48% 44%Prague 49% 39%Sydney 52% 36%Tokyo 53% 29%Vienna 56% 40%Stockholm 57% 47%Frankfurt 57% 37%Budapest 59% 44%Athens 60% 40%Paris 68% 32%Milan 76% 45%Shanghai 77% 30%Mumbai 81% 32%34

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>5c. Market Access Factors<strong>The</strong> Market Access related instrumental factors (details of theseare shown in Appendix C) used to build the GFCI are:■ Capital Access <strong>Index</strong>, Milken Institute■ Securitisation, IFSL■ Share and Bond Trading – value and volume statistics andinvestment fund trading volumes (5 separate factors), WorldFederation of Exchanges■ <strong>Global</strong> Banking Service <strong>Centres</strong>, GaWC Research■ <strong>Global</strong> Accountancy Service <strong>Centres</strong>, GaWC Research■ <strong>Global</strong> Legal Service <strong>Centres</strong>, GaWC ResearchChart 8 shows the top ten cities by GFCI ranking when only usingthe market access related factors in the prediction model.Chart 8<strong>The</strong> Top 10<strong>Financial</strong><strong>Centres</strong> Usingonly MarketAccess RelatedInstrumentalFactorsCity >LondonNew YorkHong KongSingaporeZurichFrankfurtTokyoSydneyParisChicago500 550 600 650 700 750 800Rating >Of the major financial centres, the top six do not changepositions. This is to be expected – major financial centres havegood access to financial markets. Tokyo moves up from 9th to 7thand Paris climbs into the top ten at the expense of Geneva. This isdue to the fact that Geneva is more of a niche financial centrewith strengths in private banking and asset management but isnot as strong in investment banking and the other major sectorsthat require access to financial markets.35

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>One of the reasons that London is such a strong financial centre ismarket access – not just direct access to the financial markets butaccess to customers and suppliers of professional services. Tworepresentative quotes from our online survey are:London has huge advantages in terms of itsestablished base of financial institutions andassociated businesses.All the key players, both in banking andprofessional services are based here or at leasthave offices in London, making doing business heremuch easier.New York is similar to London in this respect – it has a wellestablished cluster of professional services organisations whichservice the financial services sector.<strong>The</strong> Capital Access <strong>Index</strong> compiled by the Milken Institute rankscountries on more than 50 measures, including the strength of theirbanking systems and the diversity and efficiency of financialmarkets to generate economic conditions. Table 9 shows thecapital access index of the top 20 countries.<strong>The</strong> UK holds 1st place, with a healthy lead over Hong Kong, withSingapore and the US following closely behind. It is interesting tonote that only two years ago the UK was in 8th position with the USin 1st place.<strong>The</strong> level of Securitisation Issuance (which in effect, givesorganisations chances to convert future cash flow into a lump sumadvance) is another instrumental factor used in the GFCI model.International <strong>Financial</strong> Services, London (IFSL) provides an annualcomparison of issuance values. <strong>The</strong> latest comparison shows theUS in 1st place, well ahead of the UK which is 2nd, with Japan 3rdand Australia 4th.Other trading statistics were built into the GFCI model asinstrumental factors for market access. <strong>The</strong>se statistics were takenfrom the World Federation of Exchange’s monthly Focus report.Figures for the value and volume of share trading, the volume oftrading investment funds, as well as the value and volume of bondtrading were entered into the GFCI model. New York is the leadingcity in terms of trading shares and investment funds, with London2nd and Tokyo in 3rd place in terms of the value of share trading.Tokyo’s high ranking is due to the large volume of domesticissuance whereas New York and London have a large componentof international issuance. Shanghai rates highly in terms of36

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>Table 9<strong>The</strong> CapitalAccess <strong>Index</strong> –Top 20 CountriesCountryCapital Access <strong>Index</strong>United Kingdom 8.01Hong Kong 7.84Singapore 7.77USA 7.75Sweden 7.62Denmark 7.61Australia 7.60Norway 7.47Finland 7.46Canada 7.42Ireland 7.42Switzerland 7.39<strong>The</strong> Netherlands 7.20New Zealand 7.04Germany 6.93Malaysia 6.88Spain 6.80Chile 6.78Japan 6.76France 6.62investment fund trading, coming 2nd to New York and well aheadof any of the other financial centres.An instrumental factor focusing on access to customers is providedby Research <strong>Global</strong>ization and World Cities – Study Group &Network (GaWC) on <strong>Global</strong> Banking Service <strong>Centres</strong>. This usesdata from ten of the top 25 banks in the world concerning thelocation and size of their offices in different cities. Cities arecategorised into three groups – ‘prime’, ‘major’ and ‘minor’. <strong>The</strong>reare ten prime cities in total, including London, New York, Frankfurt,Paris, Hong Kong and Singapore. Zurich and Milan also appear inthe prime cities list, both of which appear to benefit fromeconomic clustering. Conversely, Vienna, Dublin and Chicago areall detrimentally affected by access factors and they are on the listof minor cities.GaWC also did some similar research into <strong>Global</strong> AccountancyService <strong>Centres</strong> and <strong>Global</strong> Legal Service <strong>Centres</strong>, which are thetwo instrumental factors used as indications of the access tosuppliers of professional services. For the Accountancy Service<strong>Centres</strong>, data from five of the largest accountancy firms in theworld was collected. Cities were rated based on the presence ofthese firms and classified as prime, major or minor centres foraccountancy. <strong>The</strong> prime cities include London, New York, Paris,Frankfurt and Tokyo. Minor cities include Helsinki, Dublin, Osloand Stockholm.37

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong><strong>The</strong> Legal Service <strong>Centres</strong> ratings are based on the number ofoffices that law firms have in a city. Cities were classified as prime,major or minor centres for legal services. All of the top four GFCIcities are included within the ‘prime’ list of cities.38

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>5d. Infrastructure FactorsIn order to analyse the effect that infrastructure has on the GFCI,we ran the GFCI model using only the six infrastructure-relatedinstrumental factors (details of these are shown in Appendix C).<strong>The</strong> factors are:■ <strong>Global</strong> Office Occupancy Costs, DTZ■ Office Space Across <strong>The</strong> World, Cushman & Wakefield,Healey & Baker■ Competitive Alternatives Survey, KPMG■ Offices With Air Conditioning, Gardiner & <strong>The</strong>obald■ European Cities Monitor, Cushman & Wakefield, Healey & Baker■ <strong>Global</strong> Property <strong>Index</strong>, IPDChart 9 shows the top ten cities by GFCI ranking when only usingthe infrastructure related factors in the prediction model.Chart 9<strong>The</strong> Top 10<strong>Financial</strong><strong>Centres</strong>Using onlyInfrastructureRelatedInstrumentalFactorsCity >LondonNew YorkHong KongTokyoSingaporeZurichFrankfurtParisSydneyCayman Islands500 550 600 650 700 750 800Rating >Using only infrastructure related factors, London and New Yorkoccupy 1st and 2nd positions respectively and Hong Kong is in 3rd.Tokyo has jumped five positions to 4th and Paris has jumped to 8th.Both these cities are long established financial centres and havewell developed business infrastructures that have been built overthe years. <strong>The</strong> top four cities all share relatively high costs and yetare still ranked highly.39

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>Previous research 11 indicates that the availability of businessinfrastructure is seen as an extremely important factor in thecompetitiveness of a financial centre. <strong>The</strong> quality and availabilityof commercial property is an important part of infrastructure for afinancial centre. <strong>The</strong> ability to travel easily around a city (i.e. thetransport infrastructure) is another key part of businessinfrastructure.A further instrumental factor is office occupancy costs. DTZ’s<strong>Global</strong> Office Occupancy Costs and Cushman & Wakefield,Healey & Baker’s Office Space Across <strong>The</strong> World report twodifferent measures. <strong>The</strong> Cushman & Wakefield, Healey & Bakerreport focuses on total costs of occupying office space, whereasthe DTZ report looks at the straightforward rental costs ofoccupying space. Both reports place London, Paris and Tokyo atthe more expensive end of the scale, with Prague, Melbourne andBudapest at the less expensive end. A selection of scorecomparisons for these two indices is given in Table 10.11 Z/<strong>Yen</strong> Limited, op.cit,(November 2005).Table 10Selected CityScores on OfficeOccupancyCostsCity <strong>Global</strong> Office Office Space AcrossOccupancy Costs<strong>The</strong> World($ per workstation per annum) (Euros per m 2 per annum)Paris 15,700 723London 15,083 1,130Frankfurt 14,071 471New York 10,980 509Tokyo 10,444 1,119Toronto 9,768 353Dublin 9,591 525Stockholm 9,552 388Milan 8,771 425Sydney 8,202 460Seoul 8,138 523Rome 7,929 393Athens 7,571 327Madrid 7,283 414Hong Kong 7,067 1,129Vienna 6,336 300Melbourne 5,102 370Budapest 4,908 314Prague 4,108 270Beijing 3,961 296Singapore 3,926 382Shanghai 3,628 39740

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong><strong>The</strong> figure for New York in the Office Space Across the Worldlisting seems low – it should be noted that this cost includesproperty in a wider area of the city than in London where onlythe West End and City are included. <strong>The</strong> high cost of office spaceis often cited as a problem for cities like London and New York.<strong>The</strong>re seem to be two factors that mitigate this problem:■ <strong>The</strong> cost of office space is only one element in the operationalcosts and efficiency equation. Recent studies by Z/<strong>Yen</strong> 12 showthat cost per person in primary locations are higher than inother locations. Efficiency, as measured by the number ofinvestment banking trades per person, is also much higher. Thisresults in fairly similar cost per trade figures;■ <strong>The</strong> cost of office space is a matter of supply and demandand a problem of success rather than anything else. Peoplemay feel that London, for example, is very expensive. Londonis expensive because people want to rent office space there.If the demand was less, the prices would fall.We used the European Cities Monitor, an index from Cushman &Wakefield, Healey & Baker. This puts London in 1st place, a longway ahead of Paris in 2nd, with Frankfurt in 3rd. Indeed, thepositions of these 3 cities have not changed since the indexstarted in 1990. It was only in 2005 when the top five changedfor the first time with Barcelona continuing its rise up the rankings,moving ahead of Amsterdam into 5th place, after being 11thin 1990.KPMG’s Competitive Alternatives Survey compares businesscosts in 128 cities across nine industrialised countries (Canada,France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Singapore, US andUnited Kingdom). <strong>The</strong> study measures the combined impact of27 significant business cost components that are most likely tovary by location. <strong>The</strong> index places New York 1st, three pointsahead of Frankfurt, which is just ahead of London. It is notablethat Canadian cities seem to fare poorly. Vancouver’s score of96.9 (compared with New York’s top score of 112.6) makes it thehighest placed Canadian city, with Toronto scoring 96.5 andMontreal 94.3.Despite being one of the world’s leading financial centres,London is falling behind other cities when it comes to thedevelopment of its transport network. Complexity in the system,overcrowding, high prices and delays are some of the biggestconcerns expressed by those using the system regularly andthese were highlighted by many comments in our most recentonline survey for the GFCI. One representative comment is that:12 Z/<strong>Yen</strong> Limited, Cost perTrade Surveys, (2003 –2006).41

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>London suffers from horrendous transport links anda generally overpriced and unpleasantenvironment.In 2003 KPMG reported 13 that London’s record does not comparefavourably with Paris in respect of rail and metro infrastructureinvestment or the perceived effectiveness of these services.London’s record looks better in respect of light rail, rail rolling stockand buses. In 1970 London had a well-developed metro andsuburban rail network. Subsequent development has been verylimited. 38km of rail and metro has been added to the network,compared to 85km in Paris since 1970. London’s transportinfrastructure was built over a long period of time, often bycompeting companies, and much of the system is Victorian. <strong>The</strong>age and complexity of London’s rail networks, both undergroundand suburban heavy rail, inhibits their operational effectiveness ina manner not generally experienced in other cities.<strong>The</strong>re are reports that transport in London may improve. Eurostar isjoining forces with other European rail operators to offer muchfaster journey times between key European cities and with Londonset to host the Olympics in 2012, development of the transportsystem is viewed as essential by many.It is also worth noting that whilst many people complain aboutLondon’s transport infrastructure, it has been less efficient than inmany competing cities for several decades and this has notprevented London becoming a leading global financial centre. Itis interesting to note that people working in London rate thetransport infrastructure as poor but the international perspective isvery different. Cushman & Wakefield, Healey & Baker’s researchshows that the international visitor rates London’s transportinfrastructure as the best in Europe. Clearly people who do notcommute regularly but travel in London outside peak hours thinkthat the system is very good.13 KPMG, ComparativePublic TransportInvestment in MajorEuropean Cities,Corporation of London(November 2003).42

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong> <strong>Index</strong>5e. General Competitiveness FactorsIn some financial centres, many of the competitiveness factorscome together and form what might be described as acompetitive critical mass where the whole is greater than the sumof the parts. <strong>The</strong> top cities of the GFCI, especially London and NewYork, demonstrate this critical mass of general competitiveness.<strong>The</strong> GFCI model uses eight general competitiveness relatedinstrumental factors (details of these are shown in Appendix C).<strong>The</strong> factors are:■ Economic Sentiment Indicator, European Commission■ Super Growth Companies, Grant Thornton■ World Competitiveness Scoreboard, IMD■ Retail Price <strong>Index</strong>, <strong>The</strong> Economist■ Price Comparison <strong>Index</strong>, UBS■ Nation Brands <strong>Index</strong>, Anholt■ City Brands <strong>Index</strong>, Anholt■ <strong>Global</strong> Competitiveness <strong>Index</strong>, World Economic ForumChart 10 shows the top ten cities by GFCI ranking when only usingthe general competitiveness related factors in the predictionmodel.Chart 10<strong>The</strong> Top 10<strong>Financial</strong> <strong>Centres</strong>Using onlyGeneralCompetitivenessRelatedInstrumentalFactorsCity >LondonNew YorkChicagoHong KongTokyoMontrealTorontoSydneySingaporeZurich500 550 600 650 700 750 800Rating >43