Behinderung und internationale Entwicklung Disability and ...

Behinderung und internationale Entwicklung Disability and ...

Behinderung und internationale Entwicklung Disability and ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

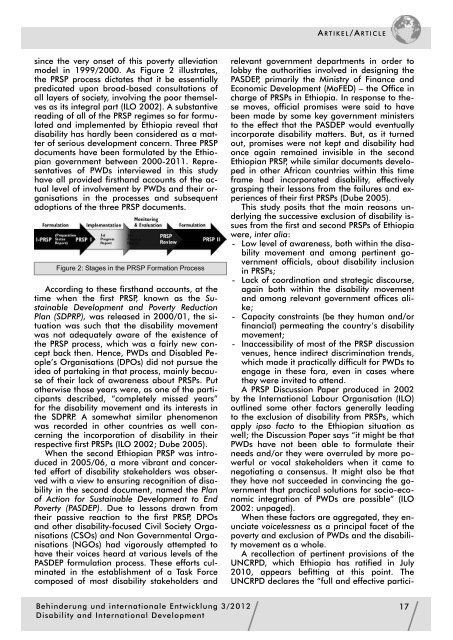

A RTIKEL/ARTICLEsince the very onset of this poverty alleviationmodel in 1999/2000. As Figure 2 illustrates,the PRSP process dictates that it be essentiallypredicated upon broad-based consultations ofall layers of society, involving the poor themselvesas its integral part (ILO 2002). A substantivereading of all of the PRSP regimes so far formulated<strong>and</strong> implemented by Ethiopia reveal thatdisability has hardly been considered as a matterof serious development concern. Three PRSPdocuments have been formulated by the Ethiopiangovernment between 2000-2011. Representativesof PWDs interviewed in this studyhave all provided firsth<strong>and</strong> accounts of the actuallevel of involvement by PWDs <strong>and</strong> their organisationsin the processes <strong>and</strong> subsequentadoptions of the three PRSP documents.Figure 2: Stages in the PRSP Formation ProcessAccording to these firsth<strong>and</strong> accounts, at thetime when the first PRSP, known as the SustainableDevelopment <strong>and</strong> Poverty ReductionPlan (SDPRP), was released in 2000/01, the situationwas such that the disability movementwas not adequately aware of the existence ofthe PRSP process, which was a fairly new conceptback then. Hence, PWDs <strong>and</strong> Disabled People’sOrganisations (DPOs) did not pursue theidea of partaking in that process, mainly becauseof their lack of awareness about PRSPs. Putotherwise those years were, as one of the participantsdescribed, “completely missed years”for the disability movement <strong>and</strong> its interests inthe SDPRP. A somewhat similar phenomenonwas recorded in other countries as well concerningthe incorporation of disability in theirrespective first PRSPs (ILO 2002; Dube 2005).When the second Ethiopian PRSP was introducedin 2005/06, a more vibrant <strong>and</strong> concertedeffort of disability stakeholders was observedwith a view to ensuring recognition of disabilityin the second document, named the Planof Action for Sustainable Development to EndPoverty (PASDEP). Due to lessons drawn fromtheir passive reaction to the first PRSP, DPOs<strong>and</strong> other disability-focused Civil Society Organisations(CSOs) <strong>and</strong> Non Governmental Organisations(NGOs) had vigorously attempted tohave their voices heard at various levels of thePASDEP formulation process. These efforts culminatedin the establishment of a Task Forcecomposed of most disability stakeholders <strong>and</strong>relevant government departments in order tolobby the authorities involved in designing thePASDEP, primarily the Ministry of Finance <strong>and</strong>Economic Development (MoFED) – the Office incharge of PRSPs in Ethiopia. In response to thesemoves, official promises were said to havebeen made by some key government ministersto the effect that the PASDEP would eventuallyincorporate disability matters. But, as it turnedout, promises were not kept <strong>and</strong> disability hadonce again remained invisible in the secondEthiopian PRSP, while similar documents developedin other African countries within this timeframe had incorporated disability, effectivelygrasping their lessons from the failures <strong>and</strong> experiencesof their first PRSPs (Dube 2005).This study posits that the main reasons <strong>und</strong>erlyingthe successive exclusion of disability issuesfrom the first <strong>and</strong> second PRSPs of Ethiopiawere, inter alia:- Low level of awareness, both within the disabilitymovement <strong>and</strong> among pertinent governmentofficials, about disability inclusionin PRSPs;- Lack of coordination <strong>and</strong> strategic discourse,again both within the disability movement<strong>and</strong> among relevant government offices alike;- Capacity constraints (be they human <strong>and</strong>/orfinancial) permeating the country’s disabilitymovement;- Inaccessibility of most of the PRSP discussionvenues, hence indirect discrimination trends,which made it practically difficult for PWDs toengage in these fora, even in cases wherethey were invited to attend.A PRSP Discussion Paper produced in 2002by the International Labour Organisation (ILO)outlined some other factors generally leadingto the exclusion of disability from PRSPs, whichapply ipso facto to the Ethiopian situation aswell; the Discussion Paper says “it might be thatPWDs have not been able to formulate theirneeds <strong>and</strong>/or they were overruled by more powerfulor vocal stakeholders when it came tonegotiating a consensus. It might also be thatthey have not succeeded in convincing the governmentthat practical solutions for socio-economicintegration of PWDs are possible” (ILO2002: unpaged).When these factors are aggregated, they enunciatevoicelessness as a principal facet of thepoverty <strong>and</strong> exclusion of PWDs <strong>and</strong> the disabilitymovement as a whole.A recollection of pertinent provisions of theUNCRPD, which Ethiopia has ratified in July2010, appears befitting at this point. TheUNCRPD declares the “full <strong>and</strong> effective partici-<strong>Behinderung</strong> <strong>und</strong> <strong>internationale</strong> <strong>Entwicklung</strong> 3/2012<strong>Disability</strong> <strong>and</strong> International Development17