Continuing Medical Education - News & Information - The Regional ...

Continuing Medical Education - News & Information - The Regional ...

Continuing Medical Education - News & Information - The Regional ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Continuing</strong> <strong>Medical</strong> <strong>Education</strong> - <strong>News</strong> & <strong>Information</strong>September 2009 - Volume 15, Issue 9Multi-Agency Edition=========================================================================Inside this issue:(bold = new content)From the Editor 1Cert & CME info 3FDNY contacts 4OLMC physicians 4CME Article 5CME Quiz 15Answer Sheet 16Citywide CME 17Exam Calendar 18-----------------------------Journal CME <strong>News</strong>letterPublished monthlyFDNY - Office of<strong>Medical</strong> Affairs9 Metrotech Center 4th flBrooklyn, NY 11201718-999-2671swansoc@fdny.nyc.govFrom the EditorImportant change to REMAC Examination feeAfter May 1, 2009 the fee for REMAC Quarterly Written and Oralsparamedic certification exams increased from $50 to $100. This is the firstincrease to the REMAC exam fee since it began in January 2002.Note that registration for all Quarterlies is limited to 50 candidates. Seethe Exam Calendar at the end of this publication for details.Keep in mind that for recertification, there is no charge for the REMACRefresher exam (Written only) so long as you meet eligibility requirements.Again, the Exam Calendar contains the details.Which protocols are on the REMAC exam?After August 1, only the July 2009 protocols are to be used in thefield and for NYC REMAC exams.After July 1, 2009 all prehospital providers should have been updatedon protocol changes by their <strong>Medical</strong> Director.Protocols are available for download at www.nycremsco.org. See asummary of changes on page 2.September 2009 – Journal CME <strong>News</strong>letter page 1 of 18

Effective July 1, 2009, NYC REMAC issued protocol revisions to be implemented after paramedics are updatedby their <strong>Medical</strong> Director. All EMS personnel should have been updated by August 1, 2009.Per REMAC, ambulance services in NYC are responsible to provide copies of the protocols to their personnel.REMAC Advisories and Protocols are available to all at www.nycremsco.orgAfter August 1, only the July 2009 protocols may be used in the field and on NYC REMAC exams.Questions may be referred to the REMAC Liaison at swansoc@fdny.nyc.gov or 718-999-2671.Outline of July 2009 NYC REMAC protocol changes:General Operating Procedures• Transport: Stroke & STEMI : removes “extremis”• Unstable Dysrhythmias: removes “CHF”• Interpretation of Protocol: clarifies application foradult and peds patients• Pharmacology Table: adds note limiting doses;removes lidocaineBLS Protocols• 404 Suspected MI: changes title; adds definition;clarifies ALS request, admin of NTG; limits ASAcontraindicationsALS Protocols• 500: Split into 2 protocols A & B• 500-A Smoke Inhalation: mandates blood drawingprior to admin hydroxocobalamin; clarifies doses• 500-B Cyanide Exposure: clarifies doses• 504-A Drug <strong>The</strong>rapy for MI & 506 APE: removesNTG paste• 511 AMS: adds titration & removes SO repeat ofnaloxone; changes PPMC repeat to all SO• 521 Head Injuries: removes lidocaine; clarifiessedation• 528 Burns: changes fluid dose & clarifiesadministration• 556 Peds A: adds titration, removes age criteria& removes SO repeat of naloxoneAppendices• Appendix C DNR: adds MOLST information• Appendix F Trauma: clarified to match GOPSeptember 2009 – Journal CME <strong>News</strong>letter page 2 of 18

FDNY ALS Division Coordinators• Citywide ALS 718-999-1738 • Division 4 718-281-3392Lt. Rudy MedinaMike Romps• Division 1 212-964-4518 • Division 5 718-979-7175Andrea KatsanakosRussell Shewchuk• Division 2 718-829-6069 • Bureau of Training 718-281-8325John LangleyHector Arroyo• Division 3 718-968-9750 • EMS Pharmacy 718-571-7620Matthew Rightmeyer & Gary SimmondsAndrew Batho----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------FDNY EMS -Division <strong>Medical</strong> Directors• Dr. Dario Gonzalez 718-281-8473 • Dr. John Freese 718-281-3861Field Response Divisions 1 & 2<strong>Medical</strong> Director of EMS TrainingUSAR/FEMA/OEM/HAZMAT DirectorOn-line <strong>Medical</strong> Control DirectorDirector of Prehospital Research• Dr. Glenn Asaeda 718-999-2666 • Dr. Doug Isaacs 718-281-8428Field Response Divisions 3, 4 & 5Associate <strong>Medical</strong> Director of TrainingUSAR/ FEMA/OEM/HAZMAT Assoc. DirectorREMSCO/REMAC Coordinator• Dr. Bradley Kaufman 718-999-1872 • Dr. Kevin Munjal 718-999-2670System-wide Quality Assurance DirectorEMS Fellow<strong>Medical</strong> Director of Emergency Dispatchand Pre-Arraignment Screening Unit----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------FDNY OLMC Physicians and ID NumbersAcosta, Juan 80286 Huie, Frederick 80300Alexandrou, Nikolaos 80282 Isaacs, Doug 80299Asaeda, Glenn 80276 Jacobowitz, Susan 80297Barbara, Paul 80306 Kaufman, Bradley 80289Ben-Eli, David 80298 Lombardi, Gary 80225Cordi, Heidi 80279 McIntosh, Barbara 80246Cox, Lincoln 80305 Munjal, Kevin 80308Freese, John 80293 Pascual, Jay 80287Giordano, Lorraine 80243 Safford, Mark 80307Gonzalez, Dario 80256 Schenker, Josef 80296Hansard, Paul 80226 Schoenwetter, David 80304Hegde, Hradaya 80262 Schneitzer, Leila 80241Hew, Phillip 80267 Silverman, Lewis 80249Soloff, Lewis 80302September 2009 – Journal CME <strong>News</strong>letter page 4 of 18

September Journal CME ArticleDifferent Numbers, Same IssueMany people in EMS, including myself, have often cited statistics that in the average system 10% of EMScalls are for pediatric patients and that 10% of those calls involve children with critical illnesses / injuries. <strong>The</strong>conclusion that is drawn from those statistics, often used to emphasize the need for frequent training, is that mostEMS providers see very few pediatric patients during their careers and even fewer pediatric patients who are truly“sick.” Because these numbers are taken from studies that are nearly twenty years old and that describe the EMSexperience in areas very different than our own City, we decided to look at our experience.Over the past five years, you and your FDNY colleagues have cared for an average of 93,000 pediatricpatients each year. This represents about 15% of the patients for whom you provided care, or about one out ofevery seven patients. So, each of you clearly has had an opportunity to perform a number of assessments onpediatric patients.But as has been suggested for the “average system,” you too (fortunately) are not called to care forcritically ill or injured pediatric patients very often. In fact, of those 93,000 pediatric patients, only 2-3% actuallyrequired any treatment and/or medication that would suggest that they were critically ill and/or injured. Soalthough you may care for a pediatric patient nearly every week, most of you will only see a single critically ill orinjured pediatric patient in a year.So what does it all mean? What it suggests to me is that even though the numbers may be a little differentfor our system / City, the underlying issue is still the same for us as it is for any other system – each of us rarelyhas the opportunity to assess a critically ill or injured pediatric patient. And, as a result, we need to periodicallyreview the assessment of our youngest patients to ensure that, when we are presented with that “sick” child, weare able to recognize the severity of their illness / injuries and act in a timely fashion.In this month’s CME article, we will review the assessment of the pediatric patient. We will begin byemphasizing the differences that exist among pediatric patients of varying ages. We will then discuss the generalassessment of the pediatric patient and pediatric vital signs. Next, we will review a quick pediatric potpourri thatincludes some specific topics that have been identified through our quality assurance efforts. And finally we willlook forward to next month’s CME article and drill in which a new approach to triage will be introduced that willinclude specific modifications for pediatric patients.Differences in AgeIt is clear that pediatric patients are not just “little adults.” <strong>The</strong>ir anatomy is different. <strong>The</strong>ir physiologyresults in different responses to illness and injury than what we may see in adults. Even the types of injuries andillnesses that we see in children differ from those of our adult patients.September 2009 – Journal CME <strong>News</strong>letter page 5 of 18

In assessing pediatric patients, it is important to recognize these differences and to take into account theirage as part of our assessment. And your interaction with the child (and their caregiver) should take thesedifferences into account.Infants (0-12 months) Infants present one of the most potentially challenging assessments. During the first30 days of life, neonates do very little. <strong>The</strong>y eat, they sleep, and they cry. And their cry is very nonspecific –resulting from hunger, pain, cold, etc. One advantage in this youngest age is that they have not yet developed arecognition of parents or strangers, meaning that they are less likely to cry just because you are present.As infants get older, their interaction with their environment rapidly changes. By two months of age, theyrecognize their parents and at six months of age they can recognize when they do not recognize someone,meaning that your mere presence and attempts to assess them can result in crying. At this same age, they also areable to recognize variations in voice, so that a calm voice will result in a more reassured response from the child.One assessment finding in this age group that can be reassuring and can help to distinguish “sick” from“not sick” is the smile. By two to three months of age, infants should have developed a social smile, track light(will look in the direction of a bright light source like your penlight), and react to a friendly voice. <strong>The</strong> infant whodoes not track light, has a blank stare, and does not interact with their caregiver (or you) is one about whom youshould be concerned.One of the greatest challenges in this age group is that they are obviously not yet verbal. On average, evena twelve month-old infant is only able to say two to three words more than “mama” and “dada”, and theappropriate use of those words for the parents only develops in the last 2-3 months of infancy.In order to obtain the best assessment possible of an infant, and recognizing these things about this agegroup, always try to examine the infant when they are being held by a parent or caregiver. Begin with the least“hands-on” parts of the assessment (i.e. watching respirations, check to see that the infant tracks light, skin color,mucous membrane condition) before moving on to more “aggressive” parts of the exam (listening to lung sounds,etc). And both to aid the exam and because of their relatively larger surface area (and risk for hypothermia), try tokeep the infant warm by exposing them only as necessary and as long as needed to perform the assessment,treatment and on-going monitoring.Toddlers (13 months – 3 years) This age group is one that can also present certain challenges to yourassessment. <strong>The</strong> changes that occur in this age group are rapid and can impact on your ability to accurately assessthe child.Mobility develops during this age, meaning that the child is no longer reliant on others to remove themfrom untoward environments. At the transition from infant to toddler (12-13 months), most children have begunto walk on their own. By 18 months they can run, and by 24 months they can begin to walk up and down stairs.This not only affects your ability to assess the “more mobile” child, but it obviously changes the types of injuriesthat you may expect to find as well as those that may be “normal.”September 2009 – Journal CME <strong>News</strong>letter page 6 of 18

Although verbal communication rapidly develops during this age, the ability to understand language andtone of voice progresses more rapidly than the ability to express words, emotion, and symptoms. So while it isimportant to actually speak to children of this age (not just the parent or caregiver) during their assessment, theyare not expected to be able to provide a reliable history. But providing them with positive reassurance and praisecan be of great assistance in allowing you to perform an accurate assessment.Toddlers also have misconceptions about injury or illness, and they often misunderstand / misinterpretthings that adults will say about their injury or illness. Keep this in mind when speaking in front of the toddler.Your ability to communicate with the parent in a calm tone, to speak in simple terms, and to involve the child inthe conversation that surrounds your assessment are key to getting the child to cooperate with the assessment.Preschoolers (4 years – 5 years) Like toddlers, children of this age continue to develop their ability tocommunicate and to understand concepts. <strong>The</strong>y are more likely to be able to relate their symptoms, but they maynot understand the terms that you are using. “Have you had a fever?” may not get a response from the child, butasking “Have you felt really hot?” may provide a more accurate answer.Like toddlers, it is important to involve the preschooler in the history and assessment. Ask questions of the childand involve them in the assessment. (“I just want to listen to your chest. Can you lift up your shirt for me?” or“Does it hurt when you…”)School Age Children (6 years – 12 years) By this age, children have begun to be able to provide anaccurate history as far as their symptoms. Even young school age children are able to relate their medical history,though they may say things such as “puffer” instead of “albuterol” or “the shots for my sugar” instead of“insulin.” Like preschoolers, they should be involved in the history-taking and their answers confirmed throughconversations with the parent.In this age group, it is important to explain procedures (why are you doing it, will it hurt, how do you doit) and to answer the child’s questions. Failure to do either is likely to make the child less trusting and less likelyto cooperate with your assessment.School age children have also begun to develop a sense of reasoning and bargaining, and they mayattempt to control their surroundings, particularly when it comes to painful procedures (for example, IVs). Forthis reason, when it is possible to do so without compromising your assessment and treatment, allowing the childto have some control may make things go a little more smoothly. For example, if it is essential that they have anIV placed, give them an option of using the left or right arm.Finally, school age children have also begun to or have developed a sense of social consciousness andprivacy. For this reason, it is important that their modesty be protected whenever possible and that their privacybe respected (don’t ask them about medical problems in front of peers, etc).Adolescents (13 years to 17 years) As most everyone knows, independence and a sense of self are veryimportant at this age. <strong>The</strong>re is little limitation with respect to an adolescent’s ability to provide an accurateSeptember 2009 – Journal CME <strong>News</strong>letter page 7 of 18

medical history or cooperate fully with your assessment; but protecting that sense of independence and self canbe of great help to you when obtaining a history and performing an assessment. Interviewing and examining theadolescent away from peers can allow for a more complete and accurate assessment.General AssessmentAs we have already mentioned, it is often helpful to begin the assessment of the pediatric patient(especially the very young) by performing the “hands-off” aspects of the examination first. Though some of usbegin our assessment of an adult by simply laying a hand on their wrist (obtaining skin condition and temperatureas well as a general assessment of pulse rate and blood pressure almost immediately), this should not be the casein the assessment of the pediatric patient.<strong>The</strong> Pediatric Assessment Triangle One tool that has been developed to assist in the “hands-off”assessment of the pediatric patient is the pediatric assessment triangle (Figure 1). <strong>The</strong> concept combines thegeneral appearance of the patient with their skin color and work of breathing in order to provide a rapid, generalassessment of the patient. In essence, you are trying to simply get an idea of whether the patient is “sick” or “notsick.”In assessing the general appearance of the child, youare looking to identify those things which would suggest thatthe child is generally ill. Any illness or injury that prevents thebrain from receiving sufficient oxygen and blood flow willmake any child initially irritable. When this deficiencybecomes more severe, the child will become lethargic or evenunconscious. In younger, nonverbal children (especiallyinfants), this can be assessed by looking at their response to aFigure 1: Pediatric Assessment Trianglestimulus. A well child will quickly quiet after a foreignstimulus is removed, while an ill (“irritable”) infant is not easily consoled. <strong>The</strong> same can be said for olderchildren – if they are not easily consoled by you or a caregiver, their irritability may be interpreted as a sign ofmore severe illness or injury. Similarly, an abnormal cry, lack of motor tone (“child is limp”) or abnormal motorresponses should suggest inadequate perfusion to the brain.Circulation to the skin can also be quickly assessed and used as a sign of overall perfusion. Childrenwhose overall perfusion is compromised (shock) will begin to compensate by shunting blood from the skintoward the more vital organs (brain, heart, lungs, kidneys). Signs of blood being shunted away from the skininclude pallor, mottling, and cyanosis.Pallor is typically the first of these signs in a patient with compensated shock. This is a finding thatsuggests that the body is purposefully shunting blood away from the skin in order to maintain blood flow in the“core” organs. While the skin may also be cool to the touch, remember that the pediatric assessment triangle isSeptember 2009 – Journal CME <strong>News</strong>letter page 8 of 18

meant to be performed without actually having to touch the child. That said, once you have touched the child anddone a more complete exam, any pale child found to have a high heart rate (see below) should be considered tobe in shock until proven otherwise.Mottling is typically considered to be a more seriousfinding than simple pallor. Mottling occurs when areas of theskin randomly experience constriction and dilation of thevessels near the surface. This occurs when the body reaches aremore advanced stage of shock. Shown in Figure 2, mottling canbe described as pale skin with areas of visible blood flowwithin the small vessels and capillaries. This results in the“marbled” or “lacy” appearance of the skin.Cyanosis, as you know, may be either a sign of hypoxia thatmay occur due to respiratory distress or severe shock (to theFigure 2: Mottled skin on the leg point that the ability to even deliver blood to the lungs to beof a neonataloxygenated is compromised). In either case, as with adults,cyanosis is best assessed in the mucous membranes. (Note: remember that in assessing newborns and neonates,cyanosis may present in the extremities – peripheral cyanosis – before it presents on the body, head, and lips –central cyanosis.)<strong>The</strong> final piece of the pediatric assessment triangle is the work of breathing. This is included in the initialassessment of the pediatric patient because, as you know, it is particularlydifficult to assess the patient’s true respiratory rate and breath sounds whenthe infant or child is crying.Begin by listening to the patient’s respirations from a distance. <strong>The</strong>following are all signs of respiratory distress in a child: grunting (indicatingan effort to maintain collapsing airways – “auto-PEEP”), stridor (indicatingupper airway obstruction), wheezing, and/or a “muffled” or abnormal voice(indicating an upper airway problem such as an infection, abscess, trauma,or mass).Also assess the patient’s positioning. So long as the child is oldenough to sit and lean forward, the tripod position (Figure 3) may be a signof increased work of breathing. <strong>The</strong> use of the tripod position is an attemptby the patient to maximally inflate their lungs while using a lot of accessorymuscles (pectoralis muscles, abdominal muscles, trapezius) to help them Figure 3: Tripod positionforce more air in and out of the thoracic cavity.September 2009 – Journal CME <strong>News</strong>letter page 9 of 18

Although it may require the assistance of the parent or caregiver to expose the child’s chest, also assessfor other signs of respiratory distress such as retractions. Retractions are a sign of increased work of breathingthat results in dramatic changes of pressure within the chest. As the child actively tries to inhale, a higher level ofnegative pressure is created in the chest. Though this may help the child to move air into the chest despite asevere asthma attack or airway obstruction, it also causes the tissue around the bony areas of the chest to bepulled in toward the chest during inspiration. As a result, these areas appear to “pull in” or “retract.” Retractionsare most commonly seen in between the ribs (intercostals retractions), above the collar bones or clavicles(supraclavicular retractions), along the lower border of the rib cage (infracostal retractions), or just beneath thesternum (substernal retractions).Finally, in infants a few other specific signs may be seen that suggest an increased work of breathing.Although infants may normally have “abdominal breathing” during the first few months of life – using theabdominal muscles and diaphragm only to move air – so called “see-saw” respirations are always consideredabnormal. This is when the chest wall and the abdomen move in opposite directions during breathing. Nasalflaring and head bobbing are also signs of an increased work of breathing in infants.So putting this all together, the idea is that you can quickly (in less than 30 seconds) assess a child withoutever touching them and yet with enough information being gathered to quickly decide if the child is “sick” or“not sick.” Upon approaching the child, simply ask yourself: Are there any signs of an increased work ofbreathing? Does the blood flow to the skin appear normal or abnormal? Does the child appear “irritable” orlethargic? If any of these three things are abnormal, the child should be considered “sick.”Physical AssessmentOnce you have completed a rapid, general assessment of the child, your history-taking and exam shouldprogress as it would for any other patient, with a few exceptions. As we noted above, the involvement of the childin the history should vary, based upon age. Particularly in younger children, more “aggressive” parts of yourexam should be saved until last (unless they are urgently needed – i.e. breath sounds in a “sick” child withrespiratory distress). And even your body position should be altered slightly.Remember that you are a medical professional, but to young children in particular, there may be anirrational association with medical care and pain (injections, immunizations, etc). Also, the fact that you wear auniform may be a source of fear for some children.Both of these things can be overcome (to some degree) by keeping yourself at or below the eye level ofthe child, by talking to them rather than just about them, and by interacting with them at an age-appropriate level.Vital SignsRecognizing abnormal vital signs in a pediatric patient is particularly important. Though it can be difficultto memorize all of the tables that have been made to describe normal and abnormal vital signs in children, a fewgeneral rules will help you to again distinguish “sick” from “not sick.” It is also important to remember that aSeptember 2009 – Journal CME <strong>News</strong>letter page 10 of 18

single set of vital signs may reveal very little about the condition of an ill or injured child, and repeating themoften is important in order to identify trends of concern.Blood Pressure This can be difficult to assess, particularly in the very young. And there are multiplereferences to use in determining if a pediatric patient’s blood pressure is normal. But two rules will help you todistinguish normal from abnormal. On the high end, a pediatric patient’s blood pressure should never exceed asystolic of 140mmHg. Such a blood pressure may be an early sign of head injury or other illness. And on the lowend, a pediatric patient’s systolic blood pressure is considered to be critically ill if it is less than 70 + (age x 2).Heart Rate <strong>The</strong> range that you may see in a pediatric patient includes some impressively high and lownumbers. Remember that when the rate is particularly high, auscultating the chest (listening to the heart) is thebest way to count.Bradycardia (slow heart rates) are concerning for the very late stages of shock or severe hypoxia and mustbe immediately addressed. In general, heart rates are considered to be critically low at a rate lower than 110minus ten points per age group. So, for infants, you should be concerned if the heart rate is less than 110-10, or100. For toddlers, 110 – 20 = 90; for preschoolers, 110-30 = 80; for school age children, 110-40 = 70; and foradolescents, 110-50 = 60.Tachycardia is one of the first signs of a severe underlying illness or injury. And the maximum heart ratethat each of us can achieve is determined by age. As a rule, a patient’s maximum heart rate should never exceed“220 minus their age.” This means that infants can (and do) achieve heart rates in excess of 200 when theyexperience severe illness or injury. And these same rates are possible in all pediatric patients.(Paramedics: This issue of tachycardia is particularly important to note. As you remember, PALSsuggests that you should be concerned about a supraventricular tachycardia in pediatric patients with a heart rate>180 or an infant with a heart rate >200. But in looking at your patients over the past five years, VERY FEWsuch patients actually had a supraventricular tachycardia. Most (>95%) had some other illness or injury that wascausing a sinus tachycardia, not a supraventricular tachycardia. So, when faced with such rates in pediatricpatients, make sure that you look for an underlying cause before treating the rate. That rate could be keepingthem alive!)Respiratory Rate <strong>The</strong> respiratory rate should be counted while not actively listening to breath sounds and,ideally, when the patient is not crying. <strong>The</strong>re are no equations that are typically used to remember the highs andlows of normal pediatric respiratory rate, but you really only need to remember three ranges. Infants typicallybreathe 40-60 times per minute, toddlers 25-40 times per minute, and children between toddlers and adolescentshave a range from 20-35.One note about assessing the respiratory rate of infants: remember that, particularly in young or prematureinfants, their respiratory pattern may normally include pauses, or periods of apnea, that last for up to 15-20seconds. For this reason it is important to assess an infant’s respiratory rate for a full minute.September 2009 – Journal CME <strong>News</strong>letter page 11 of 18

Pediatric PotpourriSince we are on the subject of pediatric care, it seemed an appropriate time to identify some of the issuesthat we have identified over the past several months with respect to pediatric care. <strong>The</strong>se include pediatric RMAs,pediatric drug dosing, pediatric airway management, pediatric cardiac arrest, and our pediatric protocols.Pediatric RMAs Among all of the things that changed in the latest version of the RMA document, onething that did not change was the lower age limit for RMAs. Because of the issues with verbal communication inyounger patients, the different conditions specific to pediatrics and the fact that each of you has very few chancesto evaluate sick patients in this age range, OLMC contact is required for all RMAs for patients under the age ofsix.Since the new RMA policy was enacted, we have been following the compliance with this and other partsof the RMA procedure. We continue to see several cases a week for which patients under the age of six have anRMA disposition without OLMC contact. Like other areas of this policy, keep in mind that this age requirementwas put into place to protect both you and the patient. And it is certainly more than a rubber stamp.In the past year, there were 688 patients under the age of six for whom you contacted OLMC for thepurpose of an RMA. In ninety-nine of those cases (nearly one in seven), the patient was subsequently transportedto the hospital. Whether this was because the parent changed their mind, because the OLMC physician was ableto convince the caretaker of the need for transport, or because some additional information / history was able tobe identified that made transport necessary, it demonstrates the reason for this requirement.Pediatric Drug Dosing As every paramedic knows, Appendix J has been removed from the protocols andthe Broselow Tape has been replaced with the term “length-based dosing device” in our protocols. But what youmay not know is how rarely we actually give medications to our pediatric patients.In the past five years, less than 5,000 medications have been given to pediatric patients each year. Whenyou consider that most of these patients received multiple medications, what it means is that each of you is likelyto only provide (and therefore have to calculate a dose of) medications to a pediatric patient once or twice a year.Like all other aspects of pediatric care, what this means is that there is a need for you to review themedication dosing for pediatric patients often. Although you should always use the length-based dosing device todetermine these doses, there will undoubtedly come a time when you have a patient in need of medications but noimmediate access to the dosing device. <strong>The</strong>refore, my recommendation is to spend just five minutes a monthreviewing the dosing for the most common pediatric medications (while driving, on the train, waiting for yourpartner to finish an ePCR) and then later check yourself to ensure that your memory was correct.September 2009 – Journal CME <strong>News</strong>letter page 12 of 18

Like so many other aspects of pediatric care, there is one equation that will nearly always help in this situation.Knowing the adult doses of the medications that you use, just divide that by 50 to get the mg/kg dosing forpediatric patients. To show how accurate this method can be and the drugs for which it may be inaccurate, Table1 lists the most common pediatric medications and their dosing.Drug Adult Dose Adult Dose / 50 Pediatric DoseAdenosine 6 mg IV 0.12 mg/kg 0.1 mg/kgAmiodarone 300 mg IV 6 mg/kg 5 mg/kgAtropine 1 mg IV 0.02 mg/kg 0.02 mg/kgDextrose 25 g IV 0.5 g/kg 0.5 g/kgDiazepam 5 mg IV 0.1 mg/kg 0.1 mg/kgDiphenhydramine 50 mg IV 1 mg/kg 1 mg/kgEpinephrine (1:1,000) 0.3 mg IM 0.006 mg/kg 0.01 mg/kgEpinephrine (1:10,000) 1 mg IV 0.02 mg/kg 0.01 mg/kgLorazepam 2 mg IV 0.04 mg/kg 0.05 mg/kgMidazolam 10 mg IM/IN 0.2 mg/kg 0.1 mg/kgTable 1: Adult versus pediatric drug dosingPediatric Airway Management Much like pediatric drug administration, the need for pediatric airwaymanagement is rare. And given the preference for basic life support airway management, the need for pediatricintubation is rare.Also like pediatric medication administration, the length-based dosing devices provide the appropriateendotracheal tube size to be used for pediatric patients and the depth to which they should be inserted. But forthat possible moment in which you find yourself with such a device and with a patient in need of immediateintubation, it is worth reviewing the other ways in which you can determine the appropriate tube size:Tube size = 4 + (age / 4)Tube size = (16 + age) / 4Tube size = patient’s pinkyTube depth = tube size x 3Particularly for infants and young children, it is important to select the correct tube size. A tube that is toolarge will damage the vocal cords. And because the uncuffed tubes are only effective when the cricoid (thenarrowest portion of the pediatric airway) forms a physiologic cuff, a tube that is too small will produce asignificant leak and possible result in effective ventilation.Pediatric Cardiac Arrest As Chief Fitton mentions in the Officer’s section below, a recent review ofpediatric cardiac arrests found that 30% did not have an AED or ALS monitor applied. For these calls, which canbecome the most stressful of all, it is critically important to take the time to provide complete and proper care,including AED or ALS monitor use.September 2009 – Journal CME <strong>News</strong>letter page 13 of 18

SEPTEMBER 2009 JOURNAL CME QUIZ1. For which of the following age groups are you required to contact OLMC prior to obtaining an RMA?a. six years of age and under c. children less than six years of age e. all of the aboveb. five years of age and under d. b and c2. Which of the following is not part of the pediatric assessment triangle?a. work of breathing d. blood flow to skinb. capillary refill e. all of the above are part of the pediatric assessment trianglec. appearance3. Which of the following is not a sign on increased work of breathing in a pediatric patient?a. stridor d. see-saw breathing in an infantb. grunting e. wheezingc. respiratory pauses of 10-15 seconds in a newborn4. Which of the following is a sign of an abnormal appearance in a pediatric patient?a. fear of strangers c. lethargy or irritability e. all of the above areb. failure of a one month-old to smile d. an infant who is easily consolablev5. Which of the following is a sign of abnormal blood flow to the skin in a pediatric patient?a. mottling c. cyanosis e.b. pallor d. flushingmore than one of theabove is correct6. Which of the following is not a common way of determining the proper ETT size for a pediatric patient?a. (age + 16) / 4 c. size of the medic’s little finger e. all of the aboveb. 4 + (age / 4) d. length-based dosing device7. All of the following are correct regarding ALS Protocols 528 and 529 except:a. both protocols require OLMC contact prior to medication administration.b. both protocols allow for medication administration without OLMC contact.c. both protocols allow for the treatment of both adult and pediatric patients.d. both protocols include weight-based dosing that may be used for pediatrics.c. all of the above are correct.8. Which of the following is true regarding pediatric cardiac arrests?a. Ventricular fibrillation may occur as often as it does in adults. e.b. V-fib may more rapidly progress to asystole as compared to adults.c. Placement of an ETT that is too small may result in ineffective ventilation.d. 30% of peds are not treated with an ALS monitor or AED.All of the above arecorrect.9. When placing an endotracheal tube in a pediatric patient without a reference such as a length-based dosing device,which of the following may be used to determine the correct tube depth?a. age + 4 c. tube size x 4 e. none of the aboveb. tube size x 3 d. tube size x age10. Which of the following is incorrect regarding pediatric tachycardia?a. Infants with heart rates > 200 should be assessed for SVT.b. Children with heart rates

Based on the CME article, place your answers to the quiz on this answer sheet.Respondents with a minimum grade of 80% will receive 1 hour of Online/Journal CME.---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Please submit this page only once, by one of the following methods:• FAX to 718-999-0119 or• MAIL to FDNY OMA, 9 MetroTech Center 4th flr, Brooklyn, NY 11201---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Contact the Journal CME Coordinator at 718-999-2790:• three months before REMAC expiration for a report of your CME hours.• for all other inquiries.Monthly receipts are not issued. You are strongly advised to keep a copy for your records.---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Note: if your information is illegible, incorrector omitted you will not receive CME credit.check one: EMT Paramedic _______________other________________________________________________Name________________________________________________NY State / REMAC # or “n/a” (not applicable)________________________________________________Work Location________________________________________________Phone number________________________________________________Email addressSubmit answer sheet bythe last day of this month.1.2.3.4.5.6.7.8.9.10.September 2009CME QuizRequired forBLS & ALSprovidersRequired forALSproviders onlySeptember 2009 – Journal CME <strong>News</strong>letter page 16 of 18

Citywide CME – September 2009Sessions are subject to change without notice. Please confirm through the listed contact.Boro Facility Date Time Topic Location Host ContactBKBrooklynHospital1 st Wed 0800-0900 Lecture121 Dekalb Ave,Mazer Lecture Room near EDDr Lehrfeld David Lehrfeld MD 503-961-5113Kingsbrook TBA TBA TBA: call to inquire ED Conference Room Dr Hew Manny Delgado 718-363-6644Lutheran 4 th Wed 1730-1930 Call Review RSVP Call for location Dr ChitnisDale Garcia 718-630-7230dgarcia@lmcmc.comMNNYPresbyterianTBA TBA TBA: call to inquire Weill Auditorium,enter at E 69 St and York AveDr. Samuels212-746-0885 x2QNFDNY-BOT9/2310/2811/181030-1430 Call Review or Lecture Fort Totten Bldg 325FDNY<strong>Medical</strong>Directorsswansoc@fdny.nyc.orgFlushing Hosp 3 rd Wed 1330-1530 Call Review Board Room Dr Crupi Mordechai Lax 718-240-5570NYH Queens Mondays 1600-1800 Call Review/Trauma Rounds East bldg, courtyard flr Dept of Surgery Lisa Galati 718-670-2501Mt Sinai Qns last Tues 1800-2100 Lecture 25-10 30 Ave, conf room Dr. Dean Donna Smith-Jordan 718-267-4390Parkway Hosp 3 rd Wed 1830-2130 Call Review Board Room, 1st flr pabruzzino@capitolhealthmgmt.comQueens Hosp2 nd Thurs4 th Thurs1615-1815 Call Review Emergency Dept 718-883-3070SIRichmondUMCTBA TBA TBA: call to inquire MLB conference room Dr. Ben-Eli William Amaniera 718-818-1364September 2009 – Journal CME <strong>News</strong>letter page 17 of 18

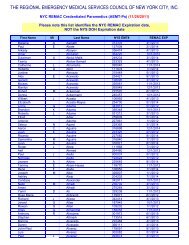

2009-10 NYC REMAC Examination ScheduleMonthREMAC Refresher Exam(Written only - CME letter required)RegistrationDeadlineExam Date(on Wednesdays)July 2009 6/30/09 7/22/09REMAC Quarterly Exam - $100 fee(Written & 3 Orals Scenarios)RegistrationDeadlineThursday7/9/09Written@18:00Thursday7/23/09Orals@09:00Thursday7/30/09NYS/DOHWrittenExamAugust 7/31/09 8/19/09 8/20/09September 8/31/09 9/23/09October 9/30/09 10/28/09Tuesday10/6/09Tuesday10/20/09Tuesday10/27/09November 10/31/09 11/18/09 11/19/09December 11/30/09 12/23/09 12/17/09January 2010 12/31/09 1/20/10Thursday1/7/10Thursday1/21/10Wednesday1/27/101/21/10February 1/31/10 2/17/10March 2/28/10 3/24/10 3/18/10April 3/31/10 4/21/10Thursday4/8/10Thursday4/22/10Thursday4/29/10May 4/30/10 5/19/10 5/20/10June 5/31/10 6/23/10 6/17/10<strong>The</strong> REMAC Refresher Written examination is offered monthly for paramedics who meet CME requirements and whose REMAC certifications are eithercurrent or expired less than 30 days. To enroll, call 718-999-7074 before the register registration deadline above. Candidates may attend an exam no more than 6months prior to expiration. Refresher exams are held at 07:00 or 18:00 hours at FDNY-EMS Bureau of Training, Fort Totten, Queens.<strong>The</strong> REMAC Quarterly Written & Orals examination is for initial certification, or for inadequate CME, or for certifications expired more than 30 days.Registrations must be postmarked by the deadline above. Email swansoc@fdny.nyc.gov for instructions. You are encouraged to register at least 30 days prior tothe exam - seating is limited. <strong>The</strong> exam fee as above is by money order only. <strong>The</strong> Quarterly is held at FDNY-EMS Bureau of Training, Fort Totten, Queens.September 2009 – Journal CME <strong>News</strong>letter page 18 of 18