Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Angola</strong>‘Failed’ <strong>yet</strong> ‘Successful’David Sogge81Working Paper / Documento de trabajoApril 2009Working Paper / Documento de trabajo

About <strong>FRIDE</strong><strong>FRIDE</strong> is an independent think-tank based in Madrid, focused on issues related to democracy and human rights; peaceand security; and humanitarian action and development. <strong>FRIDE</strong> attempts to influence policy-making and inform publicopinion, through its research in these areas.Working Papers<strong>FRIDE</strong>’s working papers seek to stimulate wider debate on these issues and present policy-relevant considerations.

<strong>Angola</strong>‘Failed’ <strong>yet</strong> ‘Successful’David SoggeApril 2009David Sogge (b. 1947) works as an independent researcher in the fields of African and International studies. Heis based in Amsterdam, where he is an associate of the Transnational Institute. Formally educated at HarvardCollege, Princeton University and the Institute of Social Studies, his professional experience in <strong>Angola</strong> began in1985. Among his publications about that country are a book, Sustainable Peace (1992), and numerous articlesand research monographs, including two published by <strong>FRIDE</strong>: <strong>Angola</strong>: Global ‘Good Governance’ Also Needed(2006) and <strong>Angola</strong>: Empowerment of the Few (2007).81Working Paper / Documento de trabajoApril 2009Working Paper / Documento de trabajo

<strong>FRIDE</strong> forms part of the initative for peacebuilding: www.initiativeforpeacebuilding.euThis paper is published with the support of the Ford Foundation.The author would like to express warm thanks to Dr. Nuno Vidal of Coimbra University (Faculdade de Economia eCentro de Estudos Sociais) for his insight and support, particularly during fieldwork in Luanda, and to <strong>FRIDE</strong> staffMariano Aguirre and Ivan Briscoe for their support and advice.Cover photo: GIANLUIGI GUERCIA/AFP/Getty Images© Fundación para las Relaciones Internacionales y el Diálogo Exterior (<strong>FRIDE</strong>) 2009.Goya, 5-7, Pasaje 2º. 28001 Madrid – SPAINTel.: +34 912 44 47 40 – Fax: +34 912 44 47 41Email: fride@fride.orgAll <strong>FRIDE</strong> publications are available at the <strong>FRIDE</strong> website: www.fride.orgThis document is the property of <strong>FRIDE</strong>. If you would like to copy, reprint or in any way reproduce all or anypart, you must request permission. The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the opinion of<strong>FRIDE</strong>. If you have any comments on this document or any other suggestions, please email us atcomments@fride.org

VExecutive summaryThis paper considers the case of <strong>Angola</strong> as aninstitutionally weak state. It is intended to contributeto the research project Institutionally Weak States:Context, Responsibilities and Responses, undertakenby the Peace, Security and Human Rights departmentof <strong>FRIDE</strong>.The analysis seeks to respond to key questions about<strong>Angola</strong> posed in the project’s guiding purposes andmethodology. These appear in three clusters:1. What are the historical taproots of conflict in<strong>Angola</strong>, and of its weak uneven state and politicalinstitutions?2. What formal and informal forces and incentives areat work in <strong>Angola</strong>’s territorial political economythat affect state and political resilience orweakness?3. What aspects of the integration of <strong>Angola</strong>’s politicaleconomy into international systems may help explainthe persistence of weak state and politicalinstitutions?After addressing these questions, the paper suggestsways European and other international decisionmakersmight look afresh at notions of state weaknessin general, and at the case of <strong>Angola</strong> in particular.Studying the <strong>Angola</strong>n case may contribute to policyabout weak states, but perhaps not along customarylines.1 USAID/Iris Center 2004, Proposed Typology in Order to ClassifyCountries Based on Performance and State Capacity, College Park: IrisCenter, University of MarylandFirst, the <strong>Angola</strong>n case suggests the limited value ofscoring and ranking states, as if they were commoditiesor football clubs. For example, influential think-tanksin the USA have classified post-war <strong>Angola</strong> as acompletely ‘failed state’, 1 a ‘severe’ case of a lowincomecountry under stress 2 and most recently as a‘critically weak’ state, 11 th of the world’s current worstcases. 3 Yet another high-profile forum, Foreign Policymagazine, has for years rated <strong>Angola</strong> as well outsidethe ranks of the seriously weak and unstable. Givenappeals for clarity and consensus among Westernpolicy elites, this discord and confusion about animportant client state is noteworthy.Second, the <strong>Angola</strong>n case suggests that confiningattention to politics ‘onshore’ leads to explanatorydead-ends. That is because <strong>Angola</strong>’s political economyis extraverted. Key processes take place ‘offshore’, insupra-national realms. Drawing attention to theextraversion of places like <strong>Angola</strong> is all the moreimportant because influential ‘expert’ organisationslike the World Bank consistently fail to do so. 4Third, <strong>Angola</strong>’s case suggests the need to probecommon assumptions like the ‘resource curse’. Manyhold that oil revenues trigger bad politics andinstability; among cruder versions is that of a punditof the Financial Times: ‘The very presence of oilturns law-abiders into thugs, and pushes nationsbackwards into chaos.’ 5 Yet recent comparativeresearch finds that oil wealth, on the contrary, tendsto stabilise regimes. Hence pursuit of general ‘lawsof petro-politics’ is a dead end; it is more useful tolook for patterns case by case in their social andhistorical settings. <strong>Angola</strong> may show signs of ‘pathdependence’, but oil was only one factor laying downthe path.Fourth, and perhaps most urgently, the case of <strong>Angola</strong>calls attention to democratic deficits generated by thehydrocarbon industry not only in fragile peripheralstates but also in advanced industrialised countries. It2 World Bank IEG 2006, Engaging with Fragile States. AnIndependent Evaluation Group Review of World Bank Support to Low-Income Countries Under Stress, Washington, D.C: World Bank3 Rice, S. and S. Patrick 2008, Index of State Weakness in theDeveloping World, Washington DC: Brookings Institution4 See for example Harrison, G. 2005, ‘The World Bank, Governanceand Theories of Political Action in Africa’, British Journal of Politicsand International Relations, 7, 240–2605 Amity Shlaes, ‘In Poorer Nations, Oil Resources Can Be a CurseUpon the People’, Financial Times, 20 June 2004<strong>Angola</strong>: ‘Failed’ <strong>yet</strong> ‘Successful’David Sogge

VIillustrates the power of the oil industry – and thenational elites who depend on it – to corrupt andundermine the legitimacy of whatever political systemit touches. Yet rules and institutions governing globalfinancial flows, tax regimes and the environmentcontinue being shaped to suit corporate interests,especially those of the hydrocarbon industry. The risksto democracies young and old are serious.This paper draws on research and commentary byothers, and on information and views obtained in 2008by the author in interviews with <strong>Angola</strong>ns, andspecialists working on issues such as revenuetransparency and human rights.Working Paper 81

ContentsGlobalised <strong>Angola</strong> – the past 1Overt and structural violence 1Economic discontinuity and polarisation 2Weak and illegitimate political institutions 2Social identities and inequalities 2Conclusion 3Globalised <strong>Angola</strong> – the present 4Oil and geopolitics 4Other extractive industries and land 6Integration in trade and investment 7Financial integration 8Political integration 9Military and security integration 11Integration – conclusion 12<strong>Angola</strong>’s onshore political economy 12Military and security systems 12Politics onshore 14Economic growth, political sociology and state resilience 17Conclusion 20Ways forward 22Coherence in Western policy and global governance 22A wider view 22A longer-term view 23Enabling a responsive state 23

1Globalised <strong>Angola</strong> –the pastWhat forces have driven <strong>Angola</strong>’s emergence as anation and polity? How have they shaped its economy,social identities and politics? This chapter offers ashort overview, laying out the background to laterchapters focused on the main research questions.Conventional wisdom holds that state fragility in Africastems chiefly from the inner drives of elites themselves.They are in the dock as greedy, corrupt, scornful ofsound policy and driven by primitive ethnic rivalries. Yetin a political economy like <strong>Angola</strong>’s, where Westerninterests have set the ground rules and incentives forfive hundred years, the power of such essentialist viewsto explain anything is not great. <strong>Angola</strong>’s polity may bebetter understood by assessing the interplay of anumber of factors:• unremitting violence, both overt and structural;• an economy geared to serve outside interests;• a state apparatus and politics based on generationsof dependent, territorially weak, militarised,centralised and corrupted processes designed forcolonial purposes and thus ipso facto antidemocratic;• inequalities generated by uneven and extraverteddevelopment;• public goods and services provided chiefly in responseto elites, and lacking any grounding in transparent,democratic processes;• a political space for associational life (‘civil society’)that is severely confined and largely de-politicised.Overt and structural violenceIn the twentieth century, <strong>Angola</strong> enjoyed only abouttwenty years without war. This was the period 1941to 1961, between the last colonial militarycampaigns and the first open anti-colonial revolts.However, <strong>Angola</strong>ns in daily life have for generationsfaced less overt forms of violence: repression,alienation and preventable poverty. Such violencehelped subordinate colonial subjects and organise apredatory economy.In the four decades following 1960, <strong>Angola</strong> wentthrough spasms of open warfare, reaching crescendosin the 1980s and 1990s. Against such violence andchaos, <strong>Angola</strong>n citizens had few defenses; mosthunkered down, pursued survival strategies, especiallytaking flight across borders or to urban areas. Elitesfaced few incentives to end this disorder and many toturn it to their own advantage.<strong>Angola</strong>’s emergence to self-determination took placeamidst geo-political contention. First, facingsetbacks in Vietnam and insurgencies elsewhere, theUnited States sought to contain and roll backcommunism. It found itself typically wrong-footedwhen in 1974 its Portuguese client regime collapsed,largely under the burden of its wars in Africa.Second, facing new and successful assertivenessamong oil producing countries, the US governmenthad few hesitations about using force to set the termsof access to <strong>Angola</strong>n oil. Foreshadowing its invasionof Iraq three decades later, it opened a covert war in<strong>Angola</strong>, making use of regional proxies in Zaire andSouth Africa.Yet throughout this assault, corporate power took adifferent position. American corporations pumped andre-sold <strong>Angola</strong>n oil, furnished <strong>Angola</strong> with Boeingairliners and facilitated capital flight to Wall Streetand tax havens. By trading with the <strong>Angola</strong>n enemy,they easily recouped the hundreds of millions spent onmaking war against it.Today that US-led covert war to ‘roll back’ communismis referred to as a civil war -– thus airbrushing away itsgeopolitical drivers. While contentious politics in thepost-independence period were probably inevitable in<strong>Angola</strong> (as in many other African polities), theduration and destructive force of the conflict can onlybe understood by factoring in the geopolitics of thetime.<strong>Angola</strong>: ‘Failed’ <strong>yet</strong> ‘Successful’David Sogge

2Economic discontinuity andpolarisationThe hasty and vengeful departure of most Portuguesesettlers in 1975 and the onset of expanded warfaretriggered the collapse of most formal industry andcommerce. From a high degree of self-reliance, <strong>Angola</strong>began to import food and other basic goods, mainlythose needed by city dwellers. Small farmers faced a‘goods famine’, thereby reducing incentives and meansto produce surpluses. The war, and resulting forcedurbanisation, were the final blows to a sophisticatedcommercial agrarian economy. The post-colonialperiod might just as accurately be termed the ‘postagrarian’period.Turbulence and discontinuity have been <strong>Angola</strong>’s fate.Its leading exports (slaves, rubber, sisal, coffee) haveboomed, then gone bust. Its development strategies(captive dependency, import-substitution, settlementschemes, Soviet-style planning) have come and gone.These cycles left behind few capacities, traditions,infrastructure or institutions for periods that followed.There was little Schumpeterian ‘creative destruction’,as the losses swamped out the gains. What hasremained constant, however, is the commandingposition of foreign capital, allied with repressive andadministrative powers of the state.Weak and illegitimate politicalinstitutions<strong>Angola</strong>’s systems of administration developedaccording to Portuguese law, custom andorganisational capacities. Those systems were weak.Under more than forty years of dictatorship and abizarre creed that the colonial order was legitimateand sustainable, government became more rigid,centralised and corrupted. In rural areas the state waspresent in only rudimentary ways, if it was present atall. Alongside formal institutions were many informalnorms of the Portuguese police state, claims ofprivilege by petty officials and grand corruption bysenior officials including the military. Apart fromchurches, sports clubs and a few charities, there was noformal associational life. Political activism in civilsociety was outlawed.Organised expressions of nationalism emerged amongintellectuals in Luanda and provincial towns. ViolentPortuguese counter-measures following spontaneousupheavals in 1960 and 1961 sent many nationalistsinto exile. Nationalist parties themselves showed littleinternal coherence or anchoring among <strong>Angola</strong>ncitizens broadly. One <strong>Angola</strong>n political analyst put it asfollows:‘Although [ national parties’] programmes proclaimeddemocratic liberties as objectives of the struggle, noneof them conducted themselves in ways that wouldguarantee pluralism. […] Within each organisation,conditions of tolerance and openness to politicaldebate [were] nonexistent.’ 6In these and other ways, <strong>Angola</strong>n anti-colonial politicsforeshadowed the autocratic and violent political orderof the post-colony. The nationalist leadership inheritedno institutions or traditions on which to build aresponsive bond or social contract between citizensand the state. Even if economic collapse and war hadnot occurred, building such a new political order wouldhave posed immense challenges. But that positivescenario was eliminated from the outset; <strong>Angola</strong>’sinstitutional fragility was in this sense ‘overdetermined’.Social identities and inequalitiesUntil the late 1800s, <strong>Angola</strong> was not a country butmerely a string of coastal enclaves. Only in the 20 thcentury did its inland territory gain politicalboundaries and infrastructure. Several distinct zonesarose around crop and labour systems, transportcorridors and marketing networks. Out of fragmentedsocio-linguistic groupings, major ethnic blocscrystallised as follows (Portuguese estimates of each6 Gonçalves, J. 2003, O descontínuo processo de desenvolvimentodemocrático em <strong>Angola</strong>, paper presented at CODESRIA Conference,Gaberone, Botswana, 18/19 October 2003 [trans. D.S.]Working Paper 81

3one’s proportion of the country’s population in 1960are given in parentheses):a) in coffee-exporting north-western zones and theCabinda enclave, a diverse range of peoplesspeaking dialects of ki-Kongo (13 %);b) in a north-central band running from Luanda to theeast, where cotton was grown for export, peoplesspeaking dialects of ki-Mbundu with increasingadmixtures of Portuguese (22 %);c) in a mixed farming (maize, beans etc) zoneextending from the central coast into the centralhighlands, peoples speaking dialects of umBundu(37 %).As elsewhere in Africa, missionaries transcribed andcodified languages and other cultural markers, thereby‘inventing’ tribal identities. Through their churches,schools, health posts and charitable works, Protestantmissions quietly competed with the dominant Catholicsystem, which colluded with Portuguese colonial order.The churches’ resulting social networks stronglyshaped <strong>Angola</strong>’s regionalised and ethnically-chargedpolitics. Leaderships of the three main nationalistparties – the FNLA in the Northwest, the MPLA inLuanda and the north-central zone and UNITA in thecentral highlands - emerged from respectively Baptist,Methodist and Congregationalist institutions. 7Apart from these ‘horizontal’ divisions, there wasmarked ‘vertical’ segregation. Foreign-based rentiers,followed by various strata of settlers, formed the top ofthe social pyramid. African hierarchies were dominatedby a longstanding Creole merchant elite. Most membersof that elite were categorised as assimilados (with minorprivileges and subaltern status as colonial citizens)distinguishing them from the indigenas, the caste ofpermanently excluded Africans. There was furtherstratification in rural areas, where the Portuguese hadarbitrarily created ‘advanced’ farmers, local policemen,straw bosses and ‘traditional’ authorities –- althoughtheir popular legitimacy was often in question.7 Birmingham, D. 1992, Frontline Nationalism in <strong>Angola</strong> andMozambique, London: James CurreyLate in the colonial period, driven by governmenttaxation, forced labour systems, settler land-grabs andthe growth of commercial agriculture, most <strong>Angola</strong>nshad been absorbed into capitalism’s cash nexus as fullor part-time proletarians and petty producers. Inseveral agrarian zones, African strata of accumulatingsmallholders had emerged, among them some ofAfrica’s most advanced rural producers at the time. Yetfurther advances for <strong>Angola</strong>ns were blocked by denialof education and by further confiscations of land bysettlers and corporations.ConclusionOver hundreds of years, <strong>Angola</strong>’s foreign overlords hadput in place a political economy based on overt andstructural violence, an ever-changing but lucrativeorder serving chiefly a rentier class in the colonialmetropole and consumers in the USA and WesternEurope. Foreign interests built up a ‘limited accessorder’ that restricted privileges and rents to a narrowelite. 8 The state mirrored social hierarchies based onthe restricted allocation of assets, economic predationand a coercive, militarised approach to public order.Colonial and post-colonial elites showed no interest increating an ‘open access order’ based on citizenship forall and competitive markets. A path was laid downaround a weak but autocratic colonial state dependenton outside powers. Mediocre institutions and underskilledpeople were additional legacies. <strong>Angola</strong>nnationalist movements, their leaders imbued withnorms of a ‘limited access order’, and habituated to theuse of armed force, had no ready alternatives whenthey assumed power.8 The terms ‘limited access order’ and ‘open access order’ arediscussed in North, D.C. and others 2007, Limited Access Orders in theDeveloping World: A New Approach to the Problems of Development,Working Paper 4359, Independent Evaluation Group, Washington DC:The World Bank<strong>Angola</strong>: ‘Failed’ <strong>yet</strong> ‘Successful’David Sogge

4Globalised <strong>Angola</strong> –the presentWhat forces entwine <strong>Angola</strong> in the world economic,social, military and political order? To what incentivesdo <strong>Angola</strong>n elites mainly respond? How do those elitesassert themselves in regional and global settings?These are among the main questions addressed in thischapter.Oil and geopoliticsIn the short runOil became <strong>Angola</strong>’s top revenue-earner in 1973, amere five years after its first appearance in exportstatistics and some 18 years after pumping began atthe country’s first commercial well. Oil radically raisedthe political stakes. It led impoverished Portugal tocling more violently to her colonies. It encouraged theUnited States to promote a devastating war against<strong>Angola</strong> and at the same time make money from it. Thecombined impact of those conflicts, rising revenues andthe massive political influence of the oil industry inWestern democracies have made oil decisive in<strong>Angola</strong>’s political economy.<strong>Angola</strong>’s case illustrates the oil industry’s geo-politicalprivileges. It gets a laissez-passer across even the bestguardedideological boundaries. Until 1974, westernoil firms’ revenues bankrolled the Portuguese wareffort. Yet when the Portuguese departed, those sameoil firms effortlessly switched their allegiance to thetriumphant African leadership in Luanda. The WhiteHouse worked hard to stop the sharing of oil revenueswith the ‘Marxist Leninists’, <strong>yet</strong> American oilcompanies easily sidestepped those pressures and hadno qualms about cultivating cordial and profitablerelations with the new ‘leftist’ government. Indeed,before the US Congress, a senior American oilcompany executive defended its tax and royaltypayments on grounds that they enabled the <strong>Angola</strong>ngovernment to improve popular living conditions, thevery claim the ‘Marxist Leninists’ made to legitimatetheir struggle. 9Five of the world’s eight largest corporations –Chevron, BP, Exxon/Mobil, Royal Dutch Shell, andTotal - created the hydrocarbon sector in <strong>Angola</strong>. Theycontinue to expand their stakes there to the presentday. Alongside some smaller ones such as the ItalianENI/AGIP (27 th largest corporation in the world), theywield not only technical but also financial and politicalpower in <strong>Angola</strong> and in geo-political spheres in which<strong>Angola</strong> is embedded.<strong>Angola</strong>’s case can be understood in light of thecommanding influence the hydrocarbon industry holdsover the political classes in many Westerndemocracies, especially the United States. Thatindustry finances political parties, fields thousands oflobbyists and shapes public debate and opinion throughthe media and think tanks. 10 Also in Western capitals,hydrocarbon-exporting dictatorships and sheikdomsmake their presence felt in spending power and inregiments of public relations operatives. For their part,western politicians pay close attention to the wishes ofthose autocracies, sometimes blocking probes into theircorrupting influence in Western public life. Accordingto a leading former oil executive, Western governmentssubsidise the hydrocarbon industry to the tune of $200billion a year. 11Oil industry power affects geopolitics via nationalgovernments, but also via the scaffolds of globalgovernance. The industry codifies and enforcesinternational financial and legal mechanismsmatching corporate requirements. Among crucialmechanisms are offshore financial centres that shieldoil revenues and personal wealth from taxation.National governments also promote hydrocarbon9 Oliveira, R. S. 2007, Oil and Politics in the Gulf of Guinea, NewYork: Columbia Univ Press, p. 18210 See for example: Oil Change International. http://priceofoil.org11 Former British Petroleum CEO Lord Browne, cited in FionaHarvey ‘Axe fossil-fuel handouts, says Browne’ Financial Times, 2November 2008Working Paper 81

5investments with World Bank loans. They deploynaval, air and ground forces to secure oil shipmentsand to protect oil-producing client states. Westerngovernments have regularly promoted oil intereststhrough covert action or open invasions. In <strong>Angola</strong>’scase, the United States provided very few of its ownforces, opting instead for a covert war by way ofnational and regional proxies.royalty payments for such resources to developingcountries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, havebeen far lower than they should be.’ 15In short, <strong>Angola</strong> may be as much sinned against assinning. Its treasury, just as treasuries elsewhere,including those of richer countries where oil companiesare headquartered, is not receiving a fair share.In <strong>Angola</strong>, the political class resides onshore but isanchored financially offshore. Its power depends on itspartnership with oil corporations and the technical,financial, diplomatic and military resources theyprovide directly or effectively guarantee. Yet thepartnership is not one of equal risks and benefits. Forexample, the terms of Production Sharing Contractscushion oil corporations against price fluctuations,thereby exposing <strong>Angola</strong> to most risks of incomevolatility. 12Companies’ technical and financial control preventsoutsiders, <strong>Angola</strong>n authorities included, from knowingwith any precision what actual oil output and profitsare. Shielded by national and supra-national rulescrafted through massive lobbying, oil corporations usetransfer pricing and bank secrecy to put their revenuebeyond anyone’s tax jurisdiction. An industry expertnotes: ‘In the Gulf of Guinea, the foreigners pump theoil, and sell it to themselves (often keeping two sets ofbooks, and squirreling away the difference in Swissbank accounts).’ 13 An IMF report estimates that Gulfof Guinea oil exporting governments lose about half thevalue of oil actually exported. 14 A report on tax lossesto mineral exporting poor countries concludes that‘there is plenty of evidence that through a combinationof hard-nosed negotiating tactics and the use ofsophisticated offshore financial products and services,In international domains today, corporationseffectively face only ‘soft law’ - that is, moralpressures to operate transparently; whereas in<strong>Angola</strong> itself they are legally forbidden to reveal keyinformation. <strong>Angola</strong> remains outside the ExtractiveIndustries Transparency Initiative, although in 2004it began to release somewhat more information onoil revenues. 16 The largest operators in <strong>Angola</strong> areamong the industry’s worst performers when itcomes to publishing what their operations actuallyyield in profits or what payments they make to thegovernment. 17 This basic bargain among elites thusrests on a mutually assured denial of information tothe public.For their part, oil corporations require a crediblesovereign state, one that is solid enough to complywith contracts as enforced by international lawyers,judges and mediators and to exercise a monopoly ofcoercive power in zones relevant to the corporations.Thanks to oil revenues, the <strong>Angola</strong>n state has becomecapable of both. It remains dependent and unevenlydeveloped, but has built alliances with colludingpolitical and corporate actors abroad. As discussedbelow, <strong>Angola</strong>’s political class has used itspartnerships to acquire its own technical capacities inthe oil sector, as well as capacities in military, financialand media realms.12 Shaxson, N. 2005, ‘New approaches to volatility: dealing withthe “resource curse” in sub-Saharan Africa’, International Affairs, 81:213 Yates, D. 2004, ‘Changing Patterns of Foreign Direct Investmentin the Oil-Economies of the Gulf of Guinea’ in Rudolf Traub-Merz andDouglas Yates (eds) Oil Policy in the Gulf of Guinea, Security &Conflict, Economic Growth, Social Development, Berlin: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung14 Katz, M., and others 2004, Lifting the Oil Curse. ImprovingPetroleum Revenue Management in Sub-Saharan Africa, WashingtonDC: IMF15 ActionAid 2008, Hole in the pocket. Why unpaid taxes are themissing link in development finance, London: Action Aid, pp. 17-1816 Ferreira, P.M. 2008, State-Society Relations in <strong>Angola</strong>: Peace-Building, Democracy and Political Participation, Initiative forPeacebuilding, Madrid: <strong>FRIDE</strong>, p. 817 Transparency International 2008, Promoting RevenueTransparency. 2008 Report on Revenue Transparency of Oil and GasCompanies, Berlin: Transparency International<strong>Angola</strong>: ‘Failed’ <strong>yet</strong> ‘Successful’David Sogge

6In the longer run<strong>Angola</strong>’s known oil and gas reserves are relativelymodest, being far smaller than those of Nigeria orSaudi Arabia. Its oil output is projected to peak in2010. Between 2015 and 2018, <strong>Angola</strong>’s petrodollarbasednational budget could flip from surplus to deficitif no alternative sources of state revenue are found.The hydrocarbon sector currently absorbs aroundthree-quarters of all investment but generates only afraction of one percent of all new employment. Bycontrast, the agricultural sector absorbs less than onepercent of recorded new investment 18 but couldgenerate massive new employment.Should <strong>Angola</strong> persist in its current pattern of elitecentredconsumption and hydrocarbon-centredproduction, it will probably face a serious downturn byaround 2020. 19 The revenue shock triggered in 2008by falling oil and diamond prices (accompanied in alllikelihood by accelerated capital flight) provides aforetaste of what may lie ahead. The next decade couldsee an abrupt end to rising expectations among urbanstrata who aspire to stable middle class lifestyles. Thecurrent development model is thus a ticking politicaltime bomb. The coming decade will reveal whether thatbomb will be defused or not.Other extractive industries andlandDiamonds have linked <strong>Angola</strong> to world systems sincethe early 1900s, but with impacts rather different fromthose of the oil sector. Many diamond-digging firms areactive, most employing private or irregular armedforces. In principle a state monopoly managed underformal sector rules, alluvial diamond mining alsoinvolves informal trade and labour circuits. As of2000, an estimated 300 to 350 thousand artisanal18 BPI 2007, Estudos Económicos e Financeiros – <strong>Angola</strong>,Departamento de Estudos Económicos e Financeiros, Outubro, Lisboa:BPI19 Mitchell, J. and P. Stevens 2008, Ending Dependence. HardChoices for Oil-Exporting States, London: Chatham House (the RoyalInstitute of International Affairs)diamond miners or garimpeiros were thought to beactive; <strong>yet</strong> even after a brutal government-ledcampaign to suppress them, there were in 2007 at leastas many if not more garimpeiros. 20All these elements pose political and fiscal challengesboth to central authority and to internationalmonitoring. Diamond-trafficking paid Unita’s billsduring its last nine years of war. In 1994, an abortivepeace settlement allocated control over five diamondareas to Unita; in 2002 this elite bargain was renewed,this time with success. Separatist movements in themain diamond zones of Lunda North and Lunda Southhave emerged, but have been held in check throughagreements among political and military elites abouteach one’s shares of diamond revenues. Transparencyhas been even weaker than in the hydrocarbon sector,although UN and civil society pressures have broughtformal diamond trading circuits under a permanentpublic spotlight. These get attention because theyinvolve major international players, such as the DeBeers monopoly.Other extractive industries such as iron ore, granite andmarble are far less lucrative, but control over them islikewise subject to limited access in the service ofinternationalised elite bargains. The same logic holdsfor access to land. Upward pressures on global foodprices strengthen incentives for foreign corporationssuch as Lonhro to acquire land suitable for farming orranching, either for direct use or for speculation.Chinese investors are also among those showing activeinterest in <strong>Angola</strong>n farmlands. A land law enacted in2004 protects small farmers only marginally, 21 insteadfavouring corporate interests. Such trends castshadows on the prospects for decent rural livelihoodsand an equitable distribution of income and wealth; onthe contrary, they set the scene for further socioeconomicpolarisation and conflict.20 PAC 2007, Diamond Industry Annual Review for <strong>Angola</strong> 2007,Ottawa: Partnership Africa-Canada21 Discussed in ‘A Questão da Terra em <strong>Angola</strong>. Ontem e Hoje’ F.Pacheco (coord.), Caderno de Estudos Sociais No. 1, 2005, Luanda:Centro de Estudos Sociais e Desenvolvimento; and ARD, Inc. 2007,Strengthening Land Tenure and Property Rights in <strong>Angola</strong>. Land Lawand Policy: Overview of Legal Framework, Washington DC/BurlingtonVT: USAID/ARDWorking Paper 81

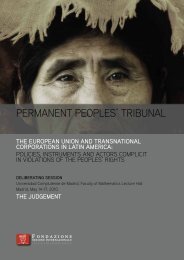

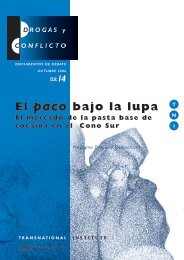

7Integration in trade andinvestmentBy 1985, ten years into the post-colonial period,<strong>Angola</strong> faced increasing disorder: more war, furtherdeterioration of basic utilities and infrastructure, arural economy in collapse and volatility of oil revenues.By 1986 these had shattered the dreams of Luanda’scentral planners about economic self-reliance,including the substitution of imports with home-madegoods. Once a major exporter of food, <strong>Angola</strong> by 1990was importing more than half its food needs, as well asmany other basic goods.As illustrated in this chart, foreign direct investmentexploded, with profits and other outflows nowsurpassing inflows in net terms. 22Consumer desires and consumer culture have sincemushroomed, fed by rapidly-growing publicity andmarketing industries in which Brazilian andPortuguese firms dominate. Advertising and consumerimages saturate national print and electronic media,whose content is largely imported from Brazil, the USand Portugal. Wants, needs and aspirations are undercontinual upward pressure as images of Westernlifestyles spread and intensify.Trade in imported goods became a key source of profitfor rich people and of informal employment for therest. Licenses to import provided access to hardcurrency credit; they thus became patronage plums,with military commanders among the first to get thefruit. Informal commerce with Zaire and South Africaflourished. Thousands of <strong>Angola</strong>ns became longdistancetraders, importing consumer goods by airfrom Brazil, Portugal and the Far East.Chinese trade and investment have radically shifted thepace and direction of <strong>Angola</strong>’s integration. Total tradevolume has grown explosively, reaching US$ 25.3billion in 2008, roughly 14 times what it had been in2000. <strong>Angola</strong> is now China’s number one tradingpartner in sub-Saharan Africa. 23 Chinese businesspresence is expanding, driven largely by national loansand lines of credit tied to its national firms andlubricated by elite interchange via trade fairs and semi-15,00010,000<strong>Angola</strong>Inward Foreign Direct Investment1974-2007in millions of US dollars5,000source: UNCTAD 20090-5,00019741979 1984 1989 1994 1999 2004FlowStock22 UNCTAD 2009, FDI Statistics, Interactive Database,http://www.unctad.org/23 In 2008, China’s trade with Brazil, whose GDP is about 25times larger than <strong>Angola</strong>’s, was only twice as large as its trade with<strong>Angola</strong>.<strong>Angola</strong>: ‘Failed’ <strong>yet</strong> ‘Successful’David Sogge

8official trade promotion agencies such as theInternational Lusophone Markets Business Association(ACIML). Competition among foreign suppliers ofgoods and services is thus sharpening, affording<strong>Angola</strong>n government elites <strong>yet</strong> more negotiating power.Portugal remains, however, <strong>Angola</strong>’s chief commercialsupplier, as well as a major investor.Financial integrationFew countries are more globalised financially than<strong>Angola</strong>. As of 1998, it was one of only seven economieswhose recorded gross external assets and liabilitiesexceeded their recorded gross domestic products. 24Since 2002, thanks to an explosion of loans, credits,capital flight and <strong>Angola</strong>n investments abroad, itsfinancial integration has only deepened.<strong>Angola</strong>’s engagement with world capital markets hasoccurred without the mediation or blessing of theBretton Woods institutions; <strong>Angola</strong> has never taken anIMF loan. However, in the late 1980s the governmentbegan introducing some standard WashingtonConsensus policy formulas, showing particularenthusiasm for measures favouring upwardredistribution. These included a stop to consumer foodsubsidies and the sale of public assets – all importantsignals to domestic and foreign business interests thatthe era of state socialism was at an end.<strong>Angola</strong>n financial surpluses have for decades excitedthe interest of foreign banks and purveyors of credit –an excitement reciprocated by <strong>Angola</strong>ns seeking to puttheir monies discretely offshore. Collusion betweenforeign and national elites has made <strong>Angola</strong> a netexporter of capital for decades. From 1985 through to2004 its estimated capital flight totalled 216 percentof recorded GDP, ranking it among the most severecases of financial haemorrhage in sub-SaharanAfrica. 2524 Lane, P. and G. M. Milesi-Ferretti 2001, ‘The External Wealth ofNations: Measures of Foreign Assets and Liabilities for Industrial andDeveloping Nations’, Journal of International Economics, Vol. 55, pp.263-394. The data offered may not have included wealth held secretly.25 Ndikumana, L. and J.K. Boyce, 2008, New Estimates of CapitalFlight from Sub-Saharan African Countries: Linkages with ExternalOutflows take place through a mix of corporate misinvoicing,26 bribes and simple transfers by wealthyindividuals. Quantities of capital flight and uncollectedtax revenues are not known with precision. Thatmassive information deficit is a deliberate outcome ofspecial privileges granted to offshore financial centresby Western governments, in large part thanks to hardlobbying and political contributions by the financialindustry. These legal arrangements have helped makethe economic life and public governance more fragilenot only in <strong>Angola</strong>, but in many other places includingWestern democracies. 27After 2002 <strong>Angola</strong> became a hot new destination forthe financial industry, backed by enthusiastic officialsfrom Western capitals. In 2007 the US AssistantSecretary of State for Africa projected <strong>Angola</strong> as oneof the continent’s three main hubs alongside Nigeriaand South Africa. A Western diplomat told a reporter,‘There’s a general feeling that if we are not a player in<strong>Angola</strong> in the next five years we will have missed thebest opportunity in Africa.’ 28 Official banks and exportcredit agencies of Brazil, China, France, Germany,Portugal and Spain have scrambled to extend newcredit, while <strong>Angola</strong> has settled old debts. Privatebanks and insurance companies arrive every year to setup shop.World Bank assessments of <strong>Angola</strong>’s business climateare not flattering, but pro-market American thinktanks give it relatively good ratings, chiefly for its mildBorrowing and Policy Options, working paper 166, Political EconomyResearch Institute, Amherst: University of Massachusetts.www.peri.umass.edu/236/hash/61e07e4377/publication/301/. Illicitflows from Africa are poorly documented and therefore greatly understated;see Kar, D. and D. Cartwright Smith 2009, Illicit FinancialFlows from Developing Countries: 2002-2006, Washington DC: GlobalFinancial Integrity26 Over-charging on exports to <strong>Angola</strong> was the main form of tradebasedcapital flight to the USA from 2000 to 2005. Pak, S. 2006,Estimates of Capital Movements from African Countries to the U.S.through Trade Mispricing, Workshop on Tax, Poverty and Finance forDevelopment, University of Essex, 6-7 July 2006, Association forAccountancy and Business Affairs27 See documentation available on the websites of the Tax JusticeNetwork (www.taxjustice.net) and of Global Financial Integrity(www.gfip.org).28 Alec Russell, ‘Investors sign up to <strong>Angola</strong>’s miracle’ FinancialTimes, 22 August 2007Working Paper 81

9tax regime 29 and deregulated trade. 30 The USgovernment approves of its financial integrationmeasures, such as easy outward transfer of revenues. 31Indeed, more money continues to flow out of <strong>Angola</strong>than goes in, as shown, for example, in data on foreigndirect investment in the period 2005-2007. 32 Where<strong>Angola</strong>’s money actually goes is not publicly known.But if its revenues follow those of other oil exporters,the chief beneficiaries are American. In a studyentitled Recycling Petrodollars, three economists ofthe US Federal Reserve conclude, ‘Although it isdifficult to determine where the funds are firstinvested, the evidence suggests that the bulk are endingup, directly or indirectly, in the United States.’ 33Pioneered by Persian Gulf oil exporters, SovereignWealth Funds are important new state vehicles formanaging petrodollars. In 2004 <strong>Angola</strong> created such afund, the Reserve Fund for Oil. However most of<strong>Angola</strong>’s recorded offshore assets are managed by thestate holding company Sonangol. That company’s corebusiness is oil, including major shares in oil firms inGabon, Congo and Equatorial Guinea, where it alsofurnishes security advice. But it has diversified widely,including interests in Portuguese energy and bankingfirms. It may soon become owner of some major mediain Portugal. In Guinea-Bissau, one of its jointventures, <strong>Angola</strong> Bauxite, is investing hundreds ofmillions in mining and port facilities.Financial integration and self-assertion are thus welladvanced.Even in the face of rising Chinesecompetition, these arrangements have furnishedWestern elites with several major desiderata: furtherdiversification of petroleum supplies, increased29 Heritage Foundation 2008, Index of Economic Freedom.Washington DC: The Wall Street Journal and the Heritage Foundation30 Cato Institute 2008, Economic Freedom of the World: 2008Annual Report. Washington DC: Cato Institute31 US Department of State 2008, Investment Climate Statement– <strong>Angola</strong> (2007),http://www.state.gov/e/eeb/ifd/2007/32 UNCTAD 2008, World Investment Report 2008, New York andGeneva: UNCTAD, p. 29433 Higgins, M., T. Klitgaard, and R. Lerman, 2006, ‘RecyclingPetrodollars’ Current Issues in Economics and Finance, 12: 9, NewYork: Federal Reserve Bank of New Yorkrevenues to Wall Street and Western-held financialcorporations; and a burgeoning market for Westernexports and investment opportunities. Forcollaborating <strong>Angola</strong>n elites, the rewards have alsobeen considerable. This incentive system is highlygeared to the short run and built on precariousecological and economic premises, but those thingshave not made it any less compelling for participants.Having been integrated for a long time, <strong>Angola</strong> mightserve to illustrate the beneficial effects that marketfundamentalists claim about globalised finance. Butthose claims look spurious, and <strong>Angola</strong>’s case is merelyone of many. Greater financial integration does notimprove long-term economic growth of poor countries,as even a recent IMF study - with evidentdisappointment - had to conclude. 34 Tellingly, thatreport’s data were gathered before poor countriesbegan to feel the impact of the global financial crisis.As that crisis deepens, the damaging effects ofuncontrolled financial integration are now becomingclear.Political integrationFinancial and military power, and seasoned politicalexperience, have enabled <strong>Angola</strong>’s elites to negotiateterms of engagement from positions of growingstrength. As European countries jockey for energysecurity, and for lucrative markets for their goods andservices, their attention to <strong>Angola</strong> has risen.With Western democraciesThe misuse of <strong>Angola</strong>n oil revenues to advance theinterests of politicians and parties in Western Europeand the United States is one of the more notoriousexpressions of <strong>Angola</strong>’s political integration withforeign political systems. Despite high-level efforts tokeep the matter secret, sufficient information leakedout regarding French oil company payoffs to Africanand European politicians to trigger criminal34 IMF Research Department 2007, Reaping the Benefits ofFinancial Globalisation, Washington DC: International Monetary Fund<strong>Angola</strong>: ‘Failed’ <strong>yet</strong> ‘Successful’David Sogge

10prosecutions in France. Evidence that <strong>Angola</strong>n oilrevenues also taint US politics has been detected, butthe matter still awaits full investigation. 35 A closeobserver of African oil politics underscores what is atstake in the Anglo-Saxon democracies:‘In the rich English-speaking world the corruption isprobably not in the form of a grand unified Frenchstylestate conspiracy, but a more privatised,decentralised, nebulous rottenness, stemming fromthose grand, generic offshore temptations whichinsidiously poison our democracies through lobbyingand other, more nefarious schemes. The higher the oilprice, the bigger the balloons of cash, and the greaterthe threat to our democracies. Once again, oil acts likeheroin: it feels good, but the final result is catastrophic.This is not just more tedious foreign corruption. This isreally dangerous stuff.’ 36With global and regional institutionsShortly after independence in 1975, <strong>Angola</strong> became amember in good standing of the United Nations and itsaffiliates. Only much later did it join institutions whereglobal economic rules are made: the IMF in 1989 andthe GATT/WTO in 1994. In the years immediatelyafter independence <strong>Angola</strong> participated as a torchbearerof third-world nationalism in such bodies as theNon-Aligned Movement; today that interest has largelyevaporated. There is little enthusiasm for progressiveblocs such as Socialist International, despite <strong>Angola</strong>’shaving received much financial and diplomatic supportfrom Sweden and other pillars of social democracy.The government shows only perfunctory interest informal African institutions such as the African Union,the Southern African Development Community(SADC) and, since 1999, the Economic Community ofCentral African States (ECCAS), a mainlyfrancophone body, often dormant, that facilitatesengagement with donors.35 Global Witness 2002, All The President’s Men: TheDevastating Story of Oil and Banking in <strong>Angola</strong>’s Privatised War,London: Global Witness, pp. 24-2536 Shaxson, N. 2007, Poisoned Wells. The Dirty Politics ofAfrican Oil, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 101<strong>Angola</strong> has been more visible in international platformswhere it has a direct stake. Luanda has become theheadquarters of a recently-revived Nigerian initiative,the Gulf of Guinea Commission, with joint economicand security ambitions. However, it shows greatenthusiasm for the oil cartel OPEC, in which it becamea full member in 2007 and president in January 2009.In its regional politics, <strong>Angola</strong> usually acts unilaterally,sometimes with force of arms. Observers note a will toenjoy hegemony over the region and to become a‘kingmaker’ rivalling South Africa. 37 These ambitionshave not gone unnoticed in Washington DC, wherealarm bells began to ring when <strong>Angola</strong>n armed forceswent in to rescue allied regimes in the Congos andelsewhere. While some in Washington once saw <strong>Angola</strong>as a source of ‘regional destabilisation’, 38 suchanxieties have since given way to benign projections of<strong>Angola</strong> as a useful regional policeman.With the aid systemIn contrast to most other sub-Saharan Africancountries, donors and the aid system rarely mediate<strong>Angola</strong>’s political integration. Business and NGOleaders do not see the aid industry as a majordevelopmental force, and deplore the condescensionand conditionalities of the aid encounter. One veteran<strong>Angola</strong>n observer rejects the notion that, before it canbe properly aided, the country has to be integrated onterms set by donors. Rather, <strong>Angola</strong>ns wish to berespected, not berated to accept the ‘bible’ of ‘goodgovernance, transparency and accountability’, when thepreconditions for such things are not present. 39Donors have therefore never exercised the kind ofpower they have elsewhere in Africa. Since the end ofthe humanitarian emergency, their influence has fallen37 For example: Prendergast, J. and J. Bowers 2003, <strong>Angola</strong>’sSecond Chance, Brussels: International Crisis Group38 World Bank 2003, Transitional Support Strategy for theRepublic of <strong>Angola</strong>, Washington DC: World Bank, p. 739 Pacheco, F. 2006, Diplomacia, Cooperação e Negócios a Ajudaao Desenvolvimento: O Papel dos Agentes Externos em <strong>Angola</strong>, paperpresented at Conference ‘Diplomacia, Cooperação e Negócios. O Papeldos Actores Externos em <strong>Angola</strong> e Moçambique’, Instituto de EstudosEstratégicos e Internacionais (IEEI), Lisbon 27 March 2006Working Paper 81

11even further. Staff of the European Commission havenoted that ‘As with other resource rich countries, thescope for influencing the government of <strong>Angola</strong> ingeneral and on governance issues in particular islimited.’ 40 According to one informant, the donors’‘last stand’ was in 2003, when the government finisheddrafting its Anti-Poverty Strategy paper (Estratégia deCombate à Pobreza). That official statement ofpurpose now appears to be a dead letter. A non-official‘observatory’ set up with a donor subsidy in 2004 tomonitor government anti-poverty work is todaydormant.at best, in part because it lacked strong and consistentbacking from powerful member states, particularly inthe West. 42Military and security integrationAmong fighting forces on the continent, <strong>Angola</strong>’s armyhas had more experience in combat and in rapidinterventions. Those facts, plus <strong>Angola</strong>’s enormousspending power, make it an attractive partner forforeign military or security officials and theirrespective arms industries.International agencies hesitate about confronting thegovernment, even when their own institutions are atstake. In 2008 they offered few audible objections tothe closure, at government behest, of the Office of theUN High Commissioner for Human Rights in Luanda.There have been exceptions to this timidity; the UN’sSpecial Rapporteur on the right to adequate housingand the UN Special Representative on human rightsdefenders have published reports critical ofgovernment actions.Only a few international development NGOs can becounted on to express criticism. This was the case in2007, when government bullying of four <strong>Angola</strong> humanrights NGOs triggered a protest from Europeanorganisations. Foreign powers like the United Statestend to give the <strong>Angola</strong>n government the benefit of thedoubt; indeed, robust defences of <strong>Angola</strong>n policy havebeen heard from US diplomats. In general, however, the‘international community’ tends to keep its collectivehead down and its mouth shut.Between international agencies and <strong>Angola</strong>ns there islittle love lost. Surveys of opinion 41 indicate low levelsof public confidence in the United Nations. Its overallpolitical and humanitarian record has been mediocre40 Commission of the European Communities 2007, Towards anEU response to situations of fragility, Commission Staff WorkingDocument SEC(2007) 1417, Brussels: CEC, p. 3041 BBC World Service Trust 2008, Elections Study <strong>Angola</strong> 2008,London: BBC World Service Trust; Farinha, H., I.S. Emerson and J.Pinto de Andrade 2004, O Futuro Depende De Nós - <strong>Angola</strong>nosdiscutem o seu futuro político - Perspectivas dos Quimbos às Cidadesde <strong>Angola</strong>, Washington DC: National Democratic InstituteFor decades, <strong>Angola</strong>n military, security and businessplayers have been buying arms and military/securityservices in both official and shadow markets. <strong>Angola</strong>nbelligerents evaded UN sanctions in their purchases ofmassive amounts of arms at premium prices. Towardsthe end of the war, non-governmental and officialresearchers documented the huge scope of <strong>Angola</strong>nintegration with the global market in military goodsand services. 43Since the war’s end in 2002, the military and securitybranches have invested more in military training,facilities and other software; in means of surveillanceand control over civil unrest; and in the private provisionof security services. There are multiple-use goods andmultiple users. For example, since 2004 Chevron hasused Israeli-made unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) forsurveillance of territory, in collaboration with <strong>Angola</strong>’smilitary. There is evidence of increasing competitionbetween Chinese and American military establishmentsfor opportunities to win <strong>Angola</strong>’s favours; bothAmerican and Chinese training efforts have increased,and joint <strong>Angola</strong>n-US military exercises, begun in 1997,have now become routine.Western military and police training and salesprogrammes began in the 1990s. Spain’s Guardia Civilworked with <strong>Angola</strong>n police forces from 1992 to 1998,42 Lari, A. and Kevlihan, R. 2004, ‘International Human RightsProtection in Situations of Conflict and Post-Conflict. A Case Study of<strong>Angola</strong>’, African Security Review 13:443 See for example Human Rights Watch 1999, <strong>Angola</strong> Unravels.New York: HRW, pp. 92-153<strong>Angola</strong>: ‘Failed’ <strong>yet</strong> ‘Successful’David Sogge

12followed by Spanish aid for prison services. The US isincreasingly involved; in 2007, for example, itsupported the regional training (including counternarcotics)of 35 <strong>Angola</strong>n police officers. The Pentagonbegan its first active programmes in 1997; today, jointUS-<strong>Angola</strong>n military exercises have become routine.Talk of ‘terrorism’ suggests the influence of Americansecurity discourse among <strong>Angola</strong>n security elites.Integration – conclusionIn a continent marked by extraverted politicaleconomies, <strong>Angola</strong>’s is an extreme case. Its mainexport is produced increasingly offshore. Most of whatit consumes is imported from abroad. Financially it isdeeply tied to Western financial markets, and now toChinese banks as well. Political and military leverageat home and abroad depend on strategic cooperationwith foreign suppliers. In short, <strong>Angola</strong>’s politicaleconomy is deeply enmeshed with external circuits andactors.Under Portuguese rule, its economy was geared toglobal markets thanks chiefly to agrarian exports. Thatoutput stimulated consumption, which fed back intoinvestment and further production onshore. Oil andwar changed all that. They fuelled politics thatdestroyed the agrarian economy and displaced thepopulation to urban areas, which are now thedemographic centre of gravity. These urban enclavesare poorly linked with local production systems;earnings and investment capital depend on marketsdriven by consumption (mainly of hydrocarbons)elsewhere in the world, as well as by casino-likespeculation.Domestic politics therefore have little to do withreciprocal relations between citizens as payers of taxesor producers of goods on the one hand, and a politicalclass in need of those taxes and goods on the other.Crucial sources of political power stem from <strong>Angola</strong>’sreliance on global systems that supply revenue, goodsand means of coercion - all taking place increasinglyunder US diplomatic and military protection.Integration offshore thus stabilises and shapes a‘limited access order’ onshore, as described in moredetail in the following chapter.<strong>Angola</strong>’s onshorepolitical economyIn what measure do formal institutions ‘onshore’ in<strong>Angola</strong> account for state resilience or fragility? Whatpatterns and rules of power operate informally throughor around them? What incentives arise, particularlyamong elites, to maintain or challenge these rules?How might these incentives evolve in the future? Theseare among the main questions addressed in thischapter.Military and security systemsFor generations <strong>Angola</strong> has been hammered by war, itshistory ‘irrigated by the blood of the victims’. 44<strong>Angola</strong>n and non-<strong>Angola</strong>n actors in pursuit of powerand wealth have, before trying anything else, usuallytaken paths of violence and coercion. The effects havebeen cumulative. In response to the ‘rollback’ warlaunched against it, the MPLA threw together, withEast Bloc help, 45 a force that later grew into acompetent, battle-hardened army. Thanks to a US-ledcrusade against it, to a flow of petrodollars and to afree market in military goods and services, <strong>Angola</strong> istoday a highly militarised and ‘securitised’ place, onecapable of deploying forces affecting politics in otherAfrican countries.Relative to the size of its population, <strong>Angola</strong>’s military,police and paramilitary forces are the largest in sub-Saharan Africa, with the probable exception ofEritrea.44 Pélissier, R. 1986, História das Campanhas de <strong>Angola</strong>.Resistência e Revoltas 1845-1941, vol II, Lisboa: ImprensaUniversitaria, Editorial Estampa, p. 28045 Cuba was an important source of military and non-militarytechnical assistance in the period 1976-1990. See ‘Cuban interventionin <strong>Angola</strong>’, http://en.wikipedia.org/. The Soviet Union, Vietnam and EastGermany also contributed technicians, material and funds. With theexception of military capacities, little today remains of their influence.Working Paper 81

13As of 2005, close to half a million people were on thepayroll of the <strong>Angola</strong>n Armed Forces, although lessthan a third of them were on active duty. Many tensof thousands 46 more serve in regular and irregularpolice forces, the Presidential Guard and the secretservices.Alongside those public forces, private securitycompanies have grown. As of 2004, nearly twohundredprivate security agencies employed around 36thousand people, mainly in Luanda and in diamondmining zones. These firms have bought and sold in ashadowy public-private market structured more bypolitical relationships (the leading security companieshaving been acquired by senior military officers) thanby open competition.In formal terms, civilian politicians have always hadthe upper hand over the <strong>Angola</strong>n military and securitybranches. Informally, however, their authority hasdepended on pacts with senior military officials. Suchpacts have been imperative since 1977, when a violentcoup attempt by security branch officials traumatisedthe political class. That imperative grew in the 1980sas Unita and its foreign backers intensified their waragainst the government. Effective, disciplined and loyalarmed forces became a fundamental project in statebuilding.Senior figures have paid close attention to therecruitment, training discipline and compensation ofmilitary and security officials. They have done so witha close eye for the social make-up of the securitybranches, in order to reduce risks of dissension anddisloyalty. After purging a number of white andmestiço officers from the army in the early 1980s, theleadership changed its policy and took an inclusiveapproach, recruiting officers of ethnic groups fromwhich opposition parties and their insurgent armiesdrew their adherents.46 In 2008, a total of 45,544 police staff participated in a trainingprogram of some kind, according to the Interior Minister (ANGOP 12January 2009). <strong>Angola</strong>’s internal security workforce may therefore benearly twice the sub-Saharan African average of 180 police personnelper 100,000 citizens.After the war’s end in 2002, the security sectorabsorbed some of the 130,000 demobilised excombatants.Incorporation of more than 5000 formerUnita soldiers and generals into the national army andpolice force was an important gesture of reconciliation.Training and upgrading have followed, often withforeign support.The leadership has worked to cement officer corps’allegiance by cultivating personal loyalties based onboth formal benefits such as promotions and pensionsand on informal benefits. In the wave of privatisationsof the 1990s, senior military figures acquired urbanreal estate and former state farms. 47 Their routes toaccumulation included access to discounted dollarsand to commercial brokerage positions, especiallyquasi-monopolies over flows of certain imports orexports - lucrative privileges obtained throughpatronage. Backed by substantial spending (some of itoff-budget), clientalist systems keep commandstructures unified and loyal. 48 Sub-streams ofpatronage branching downward help cement politicalallegiance in other levels of society. With the importantexception of Cabinda, a modest majority of <strong>Angola</strong>nsclaim to trust the armed forces. 49Otherwise, overt police coercion has been directedchiefly toward those lacking all political protection:migrant workers in diamond zones, low-incomeresidents living on prime urban real estate andepisodic protestors such as students. Theseincreasingly face ‘hybrid’ policing - joint operations offormal police with private security services - a‘privatised’ approach in which information is legallyunobtainable, complaint procedures become dead endsand no officials can be held to account. Meanwhile, thedeployment of secret police and the use of informantsseem to be growing, penetrating even local NGOnetworks.47 Péclard, D. 2008, ‘Introduction au Thème. Les Chemins de la“Reconversion Authoritaire” en <strong>Angola</strong>’, Politique Africaine 110, p. 1548 Elite bargains built on privatisation can be fragile. In Serbia,Georgia and Azerbaijan, the award of privatised assets to favouredclients did not guarantee their political loyalties. See: Gould, J. A. andC. Sickner 2008, ‘Making market democracies? The contingent loyaltiesof post-privatisation elites in Azerbaijan, Georgia and Serbia’, Review ofInternational Political Economy. 15(5):740-76949 BBC World Service Trust 2008, Elections Study <strong>Angola</strong> 2008,London: BBC World Service Trust<strong>Angola</strong>: ‘Failed’ <strong>yet</strong> ‘Successful’David Sogge

14Risks to public security in <strong>Angola</strong> are, at first glance,serious. In successive waves of demobilisation since1992, many tens of thousands of ex-soldiers have beendumped into labour markets, where very few havefound decent jobs. Moreover, <strong>Angola</strong> is awash withprivate firearms: 21 per 100 civilians, one of thehighest ratios in the non-Western world. 50 Violentcrime is certainly present, <strong>yet</strong> its incidence is well belowwhat might be expected given the unfavourableequation of firearms-plus-jobless youth. A 2007 surveyof <strong>Angola</strong>n businesses showed much lower incidenceand effects of theft and other crimes than elsewhere inAfrica. 51 In contrast to the slums of Cape Town andsome Latin American cities, there are no criminalgangs with monopolies of violence in certain zones.Politics onshorePutting formal institutions at the serviceof informal powerExecutive’s powers to appoint or dismiss all officials ofthe judicial branch, from the Supreme Court to theAudit Court (Tribunal de Contas). But it also operatesinformally, such as by stacking key bodies like theNational Electoral Commission with ruling partyadherents.Effective powers of the Parliament (AssembleiaNacional) are highly circumscribed by its narrowmandates, minimal resources and lack of financialautonomy. 53 Although dissent may be voiced andlegislation initiated there, Parliament has servedmainly as a platform for the ruling party, a functionthat in formal terms is today absolute. The country’sfirst elections in 1992 gave the MPLA 59 percent ofall seats; those of 2008 gave it 87 percent. For allpractical purposes, the status quo of the pre-1992 onepartysystem has thus been restored. Political debateand checks-and-balances thus take place largely withinthe precincts of the party/governmental leadership,behind closed doors.According to its Constitution, <strong>Angola</strong> is aparliamentary democracy. It operates throughexecutive, legislative and judicial branches whoseseparate powers allow for checks and balances amongall three. In formal terms, the public can make its voiceheard through multiple parties, civil societyorganisations and public media. However, this formalframework is only loosely related to the ways politicsactually work. Informal rules and relationshipsprevail, usually behind the legitimating façade offormal arrangements.The reality is that <strong>Angola</strong>n politics pivot on thePresident’s office, ‘Futungo’. 52 It manages clientalistsystems through a state apparatus welded together atmany points with the dominant party, the MPLA. Thismonopoly is expressed formally, such as in the50 Small Arms Survey 2007, Geneva, (online)www.smallarmssurvey.org51 World Bank 2007 <strong>Angola</strong> Investment Climate Assessment,Washington DC: World Bank, p. 3552 Referring to Futungo de Belas, the Presidential complex on aseaside hill of Luanda from which the President and other seniorpersonages operate.A formal legal system has never been accessible toordinary <strong>Angola</strong>ns. Today the judicial branch remainsweak and subordinated to central authorities. Itsdeficits in staff and operating systems are graduallybeing addressed. Courts enjoy a certain amount ofpublic confidence. 54 But there are few precedents ofcitizens bringing suit against the authorities. 55Meanwhile government is promoting less formal andbinding approaches to dispute settlement. In 2008, itsthird year of operations, the Judicial Ombudsman’soffice (Provedoria de Justiça) registered 400 citizencomplaints. In the same year a senior official proposedthe creation of public and private Mediation Centres(Centros de Arbitragem). However, such bodies haveno mandates to enforce laws or impose legally bindingoutcomes. Instead they serve to alert the authorities to53 Isaksen, J. and others 2007, Budget, State and People. BudgetProcess, Civil Society and Transparency in <strong>Angola</strong>, Working Paper2007:7, Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute; Amundsen, I. and others2005, Accountability on the Move. The Parliament of <strong>Angola</strong>. WorkingPaper 2005:11, Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute54 BBC World Service Trust 2008, Elections Study <strong>Angola</strong> 2008,London: BBC World Service Trust55 Skaar, E. and J. Van-Dúnem 2006, Courts under Construction in<strong>Angola</strong>: What can they do for the Poor? Working Paper 2006:20,Bergen: Chr. Michelsen InstituteWorking Paper 81

15problems without requiring them to find solutions.Other semi-formal initiatives, such as provincial humanrights committees, are largely dormant.Through its command of the airwaves and powers tointimidate or buy off critics, the regime controls andcolours the information available to most of the public.Self-censorship is rampant. Comparative indexescompiled by Reporters Without Borders and FreedomHouse commonly rank <strong>Angola</strong>’s press freedoms amongthe more restricted in Africa, though not among the mostrestricted. A recent analysis by a veteran media andhuman rights activist paints a somber picture ofindependent media becoming further confined, drained ofstaff and eclipsed by state and private media which churnout pro-regime images and frivolous entertainments. 56The public at large, and probably some in the politicalclass, are kept in the dark about essential political andeconomic matters. Transparency about official budgets isamong the most restricted in the world. 57 In these ways,informed, open politics face major barriers.Sub-national politicsTerritorial government has never been strong; fortyyears of war weakened it further, even to the point ofextinction in some zones. Humiliated for years by thepresence of a Unita-led ‘republic’ in the interior andsensitive to political rumblings in Cabinda and theLundas, central authorities are hyper-alert to incipientseparatism. They have shown political sophistication inkeeping provincial elites ‘inside the tent’, in a broadinformal coalition. Central authorities steer andfinance sub-national governance in layers down to locallevels. They appoint all senior sub-national officials,and create or dissolve institutions (branches ofparastatal companies, funds, commissions,programmes, etc.) according to their wishes. While afew may consult residents at local levels, every subnationalgovernment is accountable only upward,ultimately to the top authorities in Luanda.56 Marques, R. 2009, ‘Mass media in <strong>Angola</strong>: Hegemonic poweror power to be subverted?’ Pambazuka News, 8 January,http://www.pambazuka.org/57 Open Budget Initiative 2008, Open Budget Index 2008,http://www.openbudgetindex.orgAuthority is centralised, but provincial deputies haveoccasionally been granted discretionary powers. Innegotiations with Unita, the MPLA expressedwillingness to allow the President’s choice of provincialgovernors to be influenced by electoral outcomes.Futungo has from time to time suspended provincialleaders known to be corrupt and unpopular, but alsothose known to be effective and popular (e.g. formerPrime Minister Lopo de Nascimento as ‘super’authority over three southwestern provinces in the1980s).Nevertheless, Luanda is now confident enough to tryre-organising the power pyramid again. Since 2005,with Brazilian conceptual and technical advice, a pilotproject for ‘decentralisation’ has been underway in 88key districts, home to about 70 percent of thepopulation. In 2009, all of <strong>Angola</strong>’s 167 districts areto receive US$ 5 million each to be spent according toa locally-formulated District Master Plan approved inLuanda. A Decree-Law of 2007 mandates publicconsultation on local development plans and relatedissues, thus opening modest official spaces for citizens’voices to be heard at local levels.However, forums for politics made by citizensthemselves are unwelcome. It is far from clear thatpromised electoral competition at local levels willchange that. The MPLA in any case has begunpreparing the ground in some detail; for example, tomeet gender balances mandated in law, wives of MPLAofficials are being groomed (training courses in Brazil,etc.) for elected office. The authorities emphasisegradualism in these kinds of political innovations, justas they leave no doubt that significant powers willremain in their hands.Much more importance is attached to stateadministration than to political life. The territorialreach of state agencies remains weak, but performanceof some key tasks is growing stronger. 58 The collectionof taxes, customs revenues and electricity payments is58 Going by LSE Crisis States research programme indicators.See Putzel, J. 2008, Development as State-Making Research Plans(revised), Crisis States Research Centre, manuscript<strong>Angola</strong>: ‘Failed’ <strong>yet</strong> ‘Successful’David Sogge

16improving, from a low base. The regime’s capacities toget its messages across via radio, and limit alternativemessages, are strong, certainly contributing to theMPLA’s landslide victory in the September 2008parliamentary elections. Other public sector tasks haveseen uneven advances: road surfaces and watersystems have been improved, especially in the urbanzones of salaried strata. Indicators of formal schooling- number of students, teachers and classrooms - had by2008 more than doubled over 2002 levels. Healthsystems have also expanded, but results have beenmixed. Tuberculosis rates are rising and in 2007cholera hit tens of thousands in Luanda alone.Expanded reproduction of autocratic ruleFor Futungo, what is mainly at stake is its monopoly ofpower. Indispensable to this purpose are its offshorearrangements, chiefly with oil companies and their(mainly American) political and military protectors.Onshore, Futungo’s chief concern is to block theemergence of any serious domestic challenge to itsrule, whether a separatist movement or a majorcoalition of economic or political interests able tosustain itself independently of central authorities.During the war years, the MPLA leadership ultimatelyoverpowered domestic rivals with both militarycoercion and material persuasion. It gained allegianceof former rivals by furnishing access to perks, propertyand privileged means of extracting rents and access toforeign exchange. These measures neutralised moreand more opponents, convincing most to allythemselves to the MPLA government in an everbroaderelite coalition. Those showing too much ingrouployalty or reliance on foreign economic circuitsindependently of Futungo would find themselvessuddenly denied official favours and frozen out. In themid-1990s this was the fate of a then substantialcluster of prosperous Lebanese merchants, most ofwhom subsequently left the country. Aspiring newbusiness, professional or bureaucratic groups thus facestrong incentives to ally themselves vertically ratherthan laterally, and to frustrate or quash rivals and theirproposals.The state enterprise Sonangol has been a crucialinstrument in the leadership’s hands. Created in 1976as the national oil company, it is today a big andsuccessful holding company. Together with <strong>Angola</strong>’sarmed forces, it is a competent and robust institutionin a wider context of institutional decay and fragility.A close student of oil and politics in the Gulf of Guineadescribes Sonangol as ‘the centrepiece in themanagement of <strong>Angola</strong>'s “successful failed state”.’ 59With its deep pockets and solid backing from powerfulmilitary and financial forces abroad, Futungo’s handsare free – human and organisational capacitiespermitting – to pursue its clientalist political project onits own terms. However <strong>Angola</strong>’s extraverted economyand the post-war surge in foreign investment big andsmall are creating new opportunities for accumulationbeyond the purview of the ruling party. These rangefrom formal sector business licenses and credit lines toinformal sector trading, labour and transport circuits.With external business partnerships multiplying, someobservers thus see Futungo’s control overaccumulation onshore as not absolute but relative. 60Nevertheless, although deals between big <strong>Angola</strong>nentrepreneurs and foreign businesses occur regularly,central authorities work hard to maintain tight,vertical control over access to main streams of revenueand the assets that underlie them. Hence they actroutinely to frustrate horizontal alliances or majorenterprises (formal or informal) that might allow fundsand political resources to accumulate beyond theircontrol.Flows via the foreign aid system have created tensions.During the war years, the government had ceded todonors and humanitarian NGOs some control overresources and access to populations. Today the accentis firmly on state control, whether by diplomacy, cooptation,bullying or imitation. Non-state actors andprojects receiving foreign aid are kept on a particularlyshort leash. The MPLA and Futungo have advanced59 Oliveira, R. S. 2007, ‘Business success, <strong>Angola</strong>-style:postcolonial politics and the rise and rise of Sonangol’ J. of ModernAfrican Studies, 45:4, p. 59660 Vallée, O. 2008, ‘Du Palais aux Banques: La ReproductionÉlargie du Capital Indigène’ Politique Africaine 110, p. 26Working Paper 81