DOCUMENT RESUME ED 270 509 UD 024 855 AUTHOR ... - ERIC

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 270 509 UD 024 855 AUTHOR ... - ERIC

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 270 509 UD 024 855 AUTHOR ... - ERIC

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

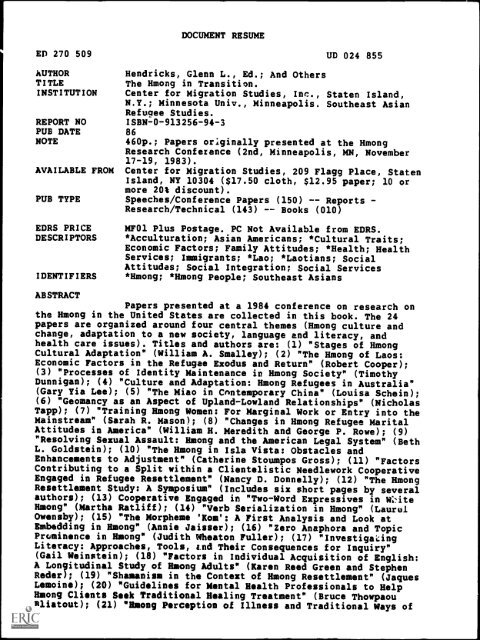

<strong>DOCUMENT</strong> <strong>RESUME</strong><strong>ED</strong> <strong>270</strong> <strong>509</strong> <strong>UD</strong> <strong>024</strong> <strong>855</strong><strong>AUTHOR</strong>Hendricks, Glenn L., Ed.; And OthersTITLEThe Hmong in Transition.INSTITUTION Center for Migration Studies, Inc., Staten Island,N.Y.; Minnesota Univ., Minneapolis. Southeast AsianRefugee Studies.REPORT NO ISBN-0-913256-94-3PUB DATE 86NOTE460p.; Papers originally presented at the HmongResearch Conference (2nd, Minneapolis, MN, November17-19, 1983).AVAILABLE FROM Center for Migration Studies, 209 Flagg Place, StatenIsland, NY 10304 ($17.50 cloth, $12.95 paper; 10 ormore 20% discount).PUB TYPE Speeches/Conference Papers (150) ReportsResearch /Technical (143) -- Books (010)<strong>ED</strong>RS PRIC<strong>ED</strong>ESCRIPTORSIDENTIFIERSMF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from <strong>ED</strong>RS.*Acculturation; Asian Americans; *Cultural Traits;Economic Factors; Family Attitudes; *Health; HealthServices; Immigrants; *Lao; *Laotians; SocialAttitudes; Social Integration; Social Services*Hmong; *Hmong People; Southeast AsiansABSTRACTPapers presented at a 1984 conference on research onthe Hmong in the United States are collected in this book. The 24papers are organized around four central themes (among culture andchange, adaptation to a new society, language and literacy, andhealth care issues). Titles and authors are: (1) "Stages of HmongCultural Adaptation" (William A. Smalley); (2) "The Hmong of Laos:Economic Factors in the Refugee Exodus and Return" (Robert Cooper);(3) "Processes of Identity Maintenance in Hmong Society" (TimothyDunnigan); (4) "Culture and Adaptation: Hmong Refugees in Australia"(Gary Yia Lee); (5) "The Miao in Cnntemporary China" (Louisa Schein);(6) "Geomancy as an Aspect of Upland-Lowland Relationships" (NicholasTapp); (7) "Training Hmong Women: For Marginal Work or Entry into theMainstream" (Sarah R. Mason); (8) "Changes in Hmong Refugee MaritalAttitudes in America" (William H. Meredith and George P. Rowe); (9)"Resolving Sexual Assault: Hmong and the American Legal System" (BethL. Goldstein); (10) "The Hmong in Isla Vista: Obstacles andEnhancements to Adjustment" (Catherine Stoumpos Gross); (11) "FactorsContributing to a Split within a Clientelistic Needlework CooperativeEngaged in Refugee Resettlement" (Nancy D. Donnelly); (12) "The AmongResettlement Study: A Symposium" (Includes six short pages by severalauthors); (13) Cooperative Engaged in "Two-Word Expressives in it*iteamong" (Martha Ratliff); (14) "Verb Serialization in Hmong" (LaurelOwensby); (15) "The Morpheme 'Rom': A First Analysis and Look atEmbedding in Huang" (Annie Jaisser); (16) "Zero Anaphora and TopicProminence in Mang" (Judith Wheaton Fuller); (17) "Investiga"cingLiteracy: Approaches, Tools, tnd Their Consequences for Inquiry"(Gail Weinstein); (18) "Factors in Individual Acquisition of English:A Longitudinal Study of Hmong Adults" (Karen Reed Green and StephenReder); (19) "Shamanism in the Context of Hmong Resettlement" (JaquesLemoine); (20) "Guidelines for Mental Health Professionals to Helpamong Clients Seek Traditional Healing Treatment" (Bruce ThowpaouBliatout); (21) "among Perception of Illness and Traditional Ways of

Healing" (Xoua Theo); (22) 'Sleep Disturbances and Sudden Death ofHmong Refugees: A Report on Field Work Conducted in the Ban VinaiRefugee Camp" (Ronald G. Munger); (23) "A Cross-Cultural Assessmentof Maternal-Child Interaction: Links to Health and Development"(Charles N. Oberg, Sharon Muret-Wagstaff, Shirley G. Moore and BrendaCumming); (24) "Undue Lead Absorption in Hmong Children" (Karl Chunand Amos S. Deinard); (25) "Attitudes of Hmong toward a MedicalResearch Project" (Marshall Hurlich, Neal R. Holtan, and Ronald G.Munger). (KH)************************************************************************Reproductions supplied by <strong>ED</strong>RS are the best that can be made **from the original document. ************************************************************************

AzMR emurneeNT 101WATIONOleos et Edmore* Remene08, t end loprovementRONAL RESOURCES INFORMATIONCENTER (<strong>ERIC</strong>)document MO been reproduced esreceived from MR onion or oreeettattondriteneting it0 Mina ottenpe neve been made to improvereproduction qualityPointe of thew or opinions UMW In Me daceleantdo not newsier* represent °Mw eowe moon or policy"PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THISMATERIAL IN MICROFICHE ONLYHAS BEEN GRANT<strong>ED</strong> BYdio F; Toni asiC.44 eaTO THE <strong>ED</strong>UCATIONAL RESOURCESINFORMATION CENTER (<strong>ERIC</strong>)."

THE HMONG IN TRANSITIONedited byGlenn L. HendricksBruce T. DowningAmos S. Deinard1986Center for Migration Studies of New York, Inc.The Southeast Asian Refugee Studies of the University of Minnesota3

The Center for Migration Studies is aneducational non-profit institute founded inNew York in 1964 to encourage and facilitatethe study of sociodemographic,economic, political, historical, legislativeand pastoral aspects of human migrationand refugee movements.The opinions expressed in this workare those of the authors.THE HMONG IN TRANSITIONA joint publication of theCenter for Migration Studiesof New York, Inc. and theSoutheast Asian RefugeeStudies Project of theUniversity of MinnesotaFirst EditionCopyright © 1986 byThe Center for Migration Studies of New York, Inc.All rights reserved No part of this book may bereproduced without permission from the publishersCenter for Migration Studies209 Flagg PlaceStaten Island, New York 10304ISBN 0-913256-94-3 (hardcover)ISBN 0-913256-95-1 (paperback)Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 85-47918Printed in the USA4

TABLE OF CONTENTSPREFACEGlenn L. HendricksMap of LaosxixvPART 1HMONG CULTURE AND CHANGE 1INTRODUCTION 3Glenn L. HendricksSTAGES OF HMONG CULTURAL ADAPTATION 7William A. SmalleyThe Stages, 7; The People of Moos Plais, 9,Typical Innovations of the Stages, 15THE HMONG OF LAOS: ECONOMIC FACTORS 23IN THE REFUGEE EXODUS AND RETURNRobert Cooper*Introductory Note, 23; The Thesis, 23; The HistoricalEvidence, 27; The Observational Evidence, 30; TheEmpirical Evidence, 32; Summary, 37; Conclusion,38PROCESSES OF IDENTITY MAINTENANCE 41IN HMONG SOCIETYTimothy Dunn IgenIntroduction, 41; The Oppositional Process, 42; TheHomeland, 45; Language, 46; Religion, 47; Kinship,49; Identity Maintenance, 50CULTURE AND ADAPTATION:55HMONG REFUGEES IN AUSTRALIAGary Yia LeesThe Traditional Productivity Base, 56; Religion andSocial Structure, 57; Impact of Resettlement, 59;Cultural Consciousness and Adaptation, 61; HmongResearch and Social Change, 66; Conclusion, 69* Indicates invited Conference keynote speaker

viTHE HMONG IN TRANSITIONTHE MIAO IN CONTEMPORARY CHINA: 73A PRELIMINARY OVERVIEWLouisa ScheinIntroduction, 73; Ethnic Classification in China, 74;The Setting, 75; The Miao as a Nationality, 76;Language and Education, 78; Some Aspects ofTradition and Change, 81; Conclusion, 83GEOMANCY AS AN ASPEdT OF 87UPLAND-LOWLAND RELATIONSHIPSNicholas TappPART 2 ADAPTING TO A NEW SOCIETY 97INTRODUCTION 99Glenn L. HendricksTRAINING HMONG WOMEN:FOR MARGINAL'WORK ORENTRY INTO THE MAINSTREAMSarah R. MasonIntroduction, 101; Federal Assistance to RefugeeJob Training,103; Development of IndochineseWomen's Programs, 104; Employment Training forSoutheast Asian Refugees in the St. Paul-MinneapolisArea, 104; Employment Training for HmongWomen in the Metropolitan Area: An Assessment,106; Conclusion, 118101CHANGES IN HMONG REFUGEE MARITAL 121ATTITUVES IN AM<strong>ERIC</strong>AW iliam H. Meredith and George P. RoweMarriage in Laos, 121; Method, 124; Population, 125;Results, 126; Conclusion and Discussion, 129RESOLVING SEXUAL ASSAULT: HMONG AND 135THE AM<strong>ERIC</strong>AN LEGAL SYSTEMBeth L. GoldsteinTHE HMONG IN ISLA VISTA: OBSTACLES AND 145ENHANCEMENTS TO ADJUSTMENTCatherine Stoumpos Gross6

TABLE OF CONTENTSviiIntroduction, 145; Methodology, 145; Obstacles toAdjustment, 146; Factors Enhancing Adjustment,150; Outlook, 154FACTORS CONTRIBUTING TO A SPLIT WITHIN A 159CLIENTELISTIC NE<strong>ED</strong>LEWORK COOPERATIVEENGAG<strong>ED</strong> IN REFUGEE RESETTLEMENTNancy D. DonnellyBackground, 160; Patron/Client Relationships, 162;Implications, 165THE HMONG RESETTLEMENT ST<strong>UD</strong>Y: 175A SYMPOSIUMINTRODUCTION 175Stephen RederPOPULATION TRENDS 179Douglas OlneySECONDARY MIGRATION TO CALIFORNIA'S 184CENTRAL VALLEYJohn FinckLANGUAGE ISSUES 187Bruce DowningHMONG EMPLOYMENT AND 193WELFARE DEPENDENCYShur Vang VangyiHMONG YOUTH AND THE HMONG FUTURE IN 197AM<strong>ERIC</strong>AMary CohnECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT ANDEMPLOYMENT PROJECTSSimon M. Fass202PART 3LANGUAGE AND LITERACYINTRODUCTION 213Bruce Downing

viiiTHE HMONG IN TRANSITIONA NOTE ON HMONG ORTHOGRAPHY 217TWO-WORD EXPRESSIVES IN 219wine HMONGMartha RatliffVERB SERIALIZATION IN HMONG 237Laurel OwensbyTHE MORPHEME "KOM": 245A FIRST ANALYSIS AND LOOKAT EMB<strong>ED</strong>DING IN HMONGAnnie Jalsser"Kom" as a Higher Verb, 245; "Kom" as aComplementizer, 250; The IdiomaticPhrase "Kom Tam", 258ZERO ANAPHORA AND TOPIC 261PROMINENCE IN HMONGJudith Wheaton FullerSentence-Level Zero Anaphora, 261; Discourse-Level Zero Anaphora, 262; Topic 1Prominence and Zero Anaphora, 268;Conclusion, 275INVESTIGATING LITERACY:APPROACHES, TOOLS, ANDTHEIR CONSEQUENCES FOR INQUIRYGall WeinsteinBackground, 279; Perspectives on the Role ofLiteracy, 280; Some Social Consequences ofLiteracy: Reflections of a Backyard Ethnographer,286279FACTORS IN INDIVIDUAL ACQUISITION 299OF ENGLISH: A LONGIT<strong>UD</strong>INAL ST<strong>UD</strong>Y OFHMONG ADULTSKaren Reed Green and Stephen RederMethods, 302; Measuring Acquisition, 307; FactorsAffecting Acquisition, 314; Conclusions, 3238

TABLE OF CONTENTSixPART 4 HEALTH CARE ISSUES 331INTRODUCTION 333Amos S. DeinardSHAMANISM IN THE CONTEXT OFHMONG RESETTLEMENTJacques LemoineIntroduction, 337; Shamanism: A Hmong Way ofPsychotherapy, 339; Spirit Helpers and Shaman'sVocation, 340; The Shaman at Work, 343;Shamanism and the Psychomentil Complex of theHmong Refugees, 345337GUIDELINES FOR MENTAL HEALTH 349PROFESSIONALS TO HELP HMONG CLIENTSSEEK TRADITIONAL HEALING TREATMENTBruce Thowpaou BilatoutHmong Traditional Beliefs About Mental Health Problems,349; Types of Traditional Hmong Healers,355; Factors to Consider When Referring a HmongClient to Traditional Healers, 359; Conclusion, 363HMONG PERCEPTION OF ILLNESS AND 365TRADITIONAL WAYS OF HEALINGXoua ThaoHmong Shamanism, 366; Herbal Medicines, 366;The Concept of Soul Loss, 367; Ways of Calling theSoul Back, 368; The Mandate of Life, 370; NaturalCauses, 370; Organic Causes, 371; Traditional Useof Herbs, 371; Magical Causes, 372; Supernatural orSpirit Causes, 373; Ways of Dealing With Spirits, 373;The Ritual Called "Ua Neeb", 375. A Turning Point,376; Conclusion, 377SLEEP DISTURBANCES AND S<strong>UD</strong>DEN DEATH OF 379HMONG REFUGEES: A REPORT ON FIELDWORKCONDUCT<strong>ED</strong> IN THE BAN VINAI REFUGEE CAMPRonald G. Munger3

xTABLE OF CONTENTSSudden Deaths of Southeast Asian Refugees in theUnited States, 380; The Ban Vinai Refugee Camp,383; Research Methods, 385; Case Reports, 386;Discussion and Conclusions, 393A CROSS-CULTURAL ASSESSMENT OF 399MATERNAL-CHILD INTERACTION:LINKS TO HEALTH AND DEVELOPMENTCharles N. Oberg, Sharon Muret-Wagstaff,Shirley G. Moore and Brenda CummingMethod, 399; Results, 403; Discussion, 410UNDUE LEAD ABSORPTION IN HMONG 417CHILDRENKarl Chun and Amos S. DelnardIntroduction, 417; Background, 417; Methods, 419;Results, 420; Summary, 422; Discussion, 423ATTIT<strong>UD</strong>ES OF HMONG TOWARDA M<strong>ED</strong>ICAL RESEARCH PROJECTMarshall Hur itch, Neal R. Ho itpn andRonald G. MungerIntroauction, 427; Background, 427; Effects ofPrevious Research Experience on Current Projects,433; The Ban Vinai Experience, 436;Discussion, 439427CONTRIBUTORS 44710

PREFACEThe second Hmong Research Conference, held at theUniversity of Minnesota on November 17-19, 1983, drewfour hundred people. While this number was far beyondour expectations, perhaps we shouldn't have been surprised.The presence of more than sixty thousand Hmongin the United Statesall engaged in the struggle to existin a culture whose social, political and economicstructures are so different from their ownhas attractedattention from many groups. Among them are educators,academic researchers, shop owners, social workers, churchcongregations, appreciators of the arts, health care providers,landlords and neighbors. Their interests rangefrom seeking solutions for immediate resettlement problemssuch as providing medical care to theoretical considerationsof the structure of the Hmong language.The conference, entitled "The Hmong in Transition,"had as its focus the formal presentation of the researchpapers collected in this volume. It also encouraged informalexchanges between those involved in helping theHmong resettle in all parts of the country. How much helpis too much help, they asked of each other. Can theHmong adapt to a new culture and also preserve their traditions?What will become of Hmong children who arebeing taught one set of values at home and another atschool? Will the Hmong be caught in the vicious cycle ofpoverty that afflicts some other minority groups in thiscountry?When this book is published, it will be almost tenyears since the first mass exodus of Hmong from Laos,precipitated by the communist Pathet Lao takeover of theLaotian government. Scholars have now had almost a decadeto study the effects of this upheaval on the Hmongnot only in the United States but also in other places oftheir exile around the world. This volume includes informationabout Hmong in France, Australia and Thailand aswell as the United States. Particularly noteworthy isthat the Hmong, whose history was borne for centuriesonly in the hearts and minds and spoken words of its people,have now been surrounded by the written word.xi11The

x11THE HMONG IN TRANSITIONpapers prepared for this conference are but cne exampleof their incorporation into mankind's written records.The international scope of the Hmong dispersion wasreflected in the backgrounds of the three invited speakersto the conference: Jacques Lemoine is associated withthe School of Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences ofthe University of Paris; Robert Cooper is a British citizenworking for the United Nations High Commissioner forRefugees in Geneva; and Gary Yia Lee, a Hmong trained asa hropologist, is a leader of the Hmong community inAustralia.The conference was sponsored by the Southeast AsianRefugee Studies Project, a research oriented group of academics,established to encourage, coordinate, and supportresearch related to refugees from Southeast Asia whohave been resettled in the United States. It is fundedprimarily by the Center for Urban and Regional Affairs atthe University of Minnesota. Additional support for theconference came from the College of Liberal Arts. A generousgrant from the National Endowment for the Humanitiesenabled us to bring the three invited speakers tothe United States.The editors are particularly indebted to the editorialassistance of Ruth Hammond, who helped to bring consistencyand readability to the twenty-five papers includedin this volume. They were written by individualstrained in a variety of disciplines, each accustomed tousing widely varying writing formats and language in thepresentation of their research. Since w were aware thata large number of readers of this book would not be academic:,one of our chief aims in editing was to makereadable the sometimes esoteric, if not idiosyncratic,language some consider the hallmark of academia. RuthHammond's considerable experience as a writer and journalisthas been instrumental in helping us to achieve ourgoal of readability.This volume, a joint production of the Center forMigration Studies and the Southeast Asian Refugee StudiesProject is also a departure from usual production methodsin publishing a book. SARS not only provided the editedversion of the papers but also prepared the papers incamera-ready format. This demanded more than typicaltypist skills and we are indebted to Pamela Anderson,without whose abilities we could not have given this12

1PREFACEx111type-set appearance to the book. In addition, DouglasOlney provided a great deal of the technical knowledbe ofcomputers and word processing which allowed us to attemptthis format. The cartographic skills of Carol Gersmehlprovided us with the map indicating areas of Hmong settlementin Southeast Asia and the location of the majorrefugee camps in Thailand in which Hmong have beenhoused..For those seeking more background information aboutthe Hmong other easily available sources include the proceeding:,of the First Hmong Research Conference, publishedas The Hmong in the West (1982), published by theCenter for Urban and Regional Affairs, University ofMinnesota, 301 19th Avenue South, Minneapolis, Minnesota55455, plus these additional publications:Barney, G. Linwood. 1967. "The Meo of Xieng KhouangProvince, Laos." In Southeast Asian Tribes, Minorities,and Nations, edited by Peter Kunstadter, pp.271-294. Princeton: Princeton University Press.Center for Applied Linguistics. 1979. "Glimpses of HmongHistory and Culture." Indochinese Refugee EducationGuides, General Information Series #16. National IndochineseClearinghouse. Washington, D.C.: Centerfor Applied Linguistics.Dunnigan, Timothy. 1982. "Segmentary Kinship in an UrbanSociety: The Hmong of St. Paul-Minneapolis. AnthrologicalQuarterly, Vol. 55(3), pp. 126-136.Geddes, William. 1976. Migrants of the Mountains: TheCu !tura! Ecology of the Biue Miao (Hmong Njua) ofThailand. Oxford, Clarendon Press.Also, a discussion on Hmong orthography can be found inPart Three, Language and Literacy, on pages 217-218.- Glenn L. HendricksMinneapolis, MinnesotaAugust 198513

\ \ Sichuan / d\ I /Guizhou ' ) Ir 4 Hunan\1,,iYunnani ..,--,, II 4. % fr i'../ isi1 ') fit- n Pi ir 4: 1101111"- 1) r A-474r'f CHINA %-l.aro%L - 1 \ - -ITiJ, II... ..."/__.. .GuangxiIleb)?).C.) 'SAv.0Hmong HomelandsandRefugee CampsBURMABAN TONG,Chlengra.I,o Hue XayIoLuaam Neua0VIETNAMTonkin- National boundary- - - Provini a boundaryHmong homelandsRefugee campsNAM VA°oChuengmalSOP TUANGA0BO 4".IP le 0 ion KhouangSayabulyT HAOILANDOKI%hen laneNONG KHAI14200 Mi.360 gra.

PART ONEHmong Culture and Change15

INTRODUCTIONGLENN L. HENDRICKSA common theme that emerged throughout the conferencein both the papers and subsequent discussions wasthat of the identification of what is representive ofHmong culture and how it has changed in the period of thediaspora. Too frequently some observers and commentatorsof the Hmong have failed to understand that the conceptof culture implicitly assumes it is dynamic and that overtime varying degrees of change will take place in any society.The rate that the change takes place is a functionor the historical situation as well as attributes ofthe culture itself. The failure to understand this leadssome to think in terms of before and after, that therewas a traditional almost unchanging way of Hmong livingthat has been severely altered by the events of the periodof flight and subsequent resettlement. That Hmonglife has been radically altered cannot be disputed butthe change must be seen as a matte. of degree. The papersin this section provide a needed corrective in assistingus to gain a longer perspective of Hmong society, particularlyin the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.It should be noted that these papers, while focusingon aspects of Hmong society and culture, touch on somebasic issues in the social sciences. Namely, what is thenature of culture? What constitutes cultural change?What is the relationship between culture and ethnic identity?Can change be directed in such fashion that it becomesdisruptive of neither culture nor ethnic identity?We need not discuss these issues here but the carefulreader will discern distinct, if not opposing, viewpointsamong the authors of the papers that follow. But the issueof change is not necessarily the exclusive arena ofthe academic. A central question asked by most of thosewho are involved in the resettlement of Hmong refugeeshas been how to accomplish the process while allowingthem to maintain their distinctive identity as Hmong.These papers provide food for thought for those responsiblefor making decis;ons about the immediate issues316

4 THE HMONG IN TRANSITIONsuch as providing housing or deciding who can speak forthe Hmong.William Smalley, a linguist who first became involvedwith the Hmong over thirty years ago while workingon a project to provide a written form of the Hmong language,sketches out a series of stages that he sees aspart of the transformation of that part of the Hmong societythat migrated to the West. He points out thatchanges had begun to evolve long before the ultimateflight from Laos. Varying forms of individual and groupbehavior in the new setting can be understood, at leastpartially, as a function of events in the past. Contrastingpatterns of community leadership that have emerged invarious areas of resettlement around the United Statescan be traced to both the introduction of education inLaos and the way in which refugee camps in Thailand wereorganized.Robert Cooper, a British anthropologist who hasworked among the Hmong in both Thailand and Laos, presentsdata arguing that in addition to the commonly understoodpolitical reasons for the Hmong flight from Laosthere were also economic motivations for the move. Histhesis is that in examining historical, empirical and observationaldata there are grounds for concluding thatconditions in Laos were such that the land could nolonger support the traditional agricultural economicbasis of Hmong life. This paper proved to be the mostwidely discussed presentation of the Conference, withmany of the Hmong present disputing his interpretation ofthe facts and events cited.Timothy Dunnigan, an anthropologist who has beenkeenly interested in the Hmong since they first arrivedin the Twin Cities in 1975, carries our discussion of theimpact of resettlement on Hmong culture further. He discussesthe process by which they are maintaining theirethnic identity even while some of the attributes whichare said to be markers of being traditional Hmong are inthe process of change. In some cases what appear to besignificant changes in group organization, for example,he identifies as latent attributes of Hmong culture whichhave manifested themselves in previous situations ofHmong history when their ethnic identity was threatened.Gary Yia Lee, part of the small Hmong group that migratedto Australia, was educated there and earned his17

INTRODUCTION 5doctorate in anthropology at the University of Sydney.Subsequently he has been a leader of the Hmong communityof Australia. In both his presentation and his commentson others' papers he was able to give a valuable insider/outsider's perspective to our discussions. He arguesthat, in the Australian case at least, there are indeedsignificant changes in the economic basis of Hmong life,social structure and religious beliefs. However, thisneed not portend a destruction of their identity asHmong, but rather must be seen as an adaptation tochanging circumstances.A particularly valuable contribution to the participantsof this Conference was the presentation by LouisaSchein about the Miao (Hmong) in contemporary China. Itwas from this group, or at least parts of this group,that the Hmong of Laos, Thailand and Vietnam migratedduring the eighteenth and early nineteenth century.Nicholas Tapp, another British-trained anthropologist,who has worked for several years studying Hmong innorthern Thailand, examines geomancy, the practice ofdivination based upon geographical and spatial features,and its historical place as an attribute of Hmong culture.He points out that while the practice has its rootsin China, it is but one of many factors to be taken intoaccount in any discussion which assume a "ideal" or traditionalHmong culture against which any change might bemeasured.18

STAGES OF HMONG CULTURAL ADAPTATIONWilliam A. SmalleyAmericans who have had contact with Hmong in theUnited States are often aware that massive change hascome to these new immigrants as they have settled here.However, many of these same Americans are unaware of thechanges in Hmong life and culture which took place inLaos and in the Thailand camps over the last generation,and before.1, for example, had had some minimal contact withHmong in Laos in the early 1950s, but was puzzled at whatseemed to be very different leadership patterns exhibitedin Lao Family Community and its layers of Hmong organizationin the Twin Cities. I was slow to realize how muchthe Hmong learned during the years of military action,wartime migration and resettlement in Laos and camp lifein Thailand. On the other hand, I occasionally see theopposite extreme of this limited understanding in otherAmericans who write about aspects of Hmong life that developedin the disruptions of the sixties or seventies asthough they were "traditional."THE STAGESIn what follows I would like to suggest severalrather self-evident stages in the modern historicalchanges which are part of Hmong experience. Each stagemanifests certain typical innovations, some of which willbe pointed out later.'1. Laos penetration stage: The time when the Hmong weremoving into Laos, when they were oriented more toChina and/or North Vietnam, when there were relativelysmall numbers, when they had to begin to learn tocope with new ethnic groups and new power structuresaround them, notably those of the Lao and the French.7 19

8 THE HMONG IN TRANSITION2. Laos traditional stage: The period when the Hmonghad become a significantly large ethnic group inLaos, but when they kept to their mountains as muchas possible, and largely avoided contact with morepowerful groups.3. Laos adaptive stage: The period when a somewhatstable relationship had been estabished between theHmong and other ethnic groups, when they had learnedways of coping with such groups, arid when they wereseeking more aggressively to take a significant placein the larger life of the Lao state.4. Laos resettlement stage: The period when increasingpercentages of the Hmong population were forced outof their villages into resettlement conglomerationswhere they typically were mingled with peoples fromother ethnic groups, where the exercise of some traditionalcultural patterns was curtailed, and wherenew cultural forces were brought to bear on them withgreat suddenness and intensity.5. Thailand camp stage.6. United States resettlement stage.I have deliberately not set dates for these stages.They are not discrete periods of time, nor did they takeplace at exactly the same time for all Hmong in all partsof Laos. Some Hmong people, some villages, some familieswere in the Laos adaptive stage when other families, othervillages, other people were still in the Laos penetrationstage. In 1974, when he was an official in the Laocoalition ministry of planring, Yang Dao (personal communication)found Hmong in border areas of Laos who stillknew Chinese but not Lao. He discovered this case of theLaos penetration stage at the same time that many Hmongelsewhere were in the Laos resettlement stage.Most Hmong who have reached the United States belong,or did belong, to groups which went through all ormost of these stages. Presumably, very few of these individualsremember when their community was in the Laospenetration stage, but all the other stages have beenexperienced by the older people, and all Hmong in the20

STAGES OF HMONG CULTURAL ADAPTATION 9United States are products of this history, with someindividuals and groups having been more strongly influencedby developments in one stage or another.THE PEOPLE OF MOOS PLAISIn the early 1950s there was a cluster of four Hmongvillages two days travel (but only sixty miles directflight) north of Luang Prabang, the Royal Capital ofLaos. This cluster is usually called Moos Plais1 by itsformer inhabitants now in the Twin Cities. The villagesat Moos Plais were relatively stable and prosperous.There was enough land so that people did not have to migrate.They had a surplus rice crop, raised animals andgrew opium. I would like to illustrate briefly the stagesof adaptation by reciting a few bits of these maple'sexperience.At least three developments epitomized the transitionof Moos Plais from the Laos traditional stage to theLaos adaptive stage. The earliest to develop was regularand frequent trade relations with the Lao. The traditionalLaos period included extensive trade, of course.Bu in the Laos adaptive stage, Hmong did not depend soexclusively on traders coming to them; they also went toLao towns in very much larger numbers and with greaterfrequency.Next was cooperation with the French/Lao militaryeffort. Initially it was simply a matter of Hmong menpatrolling under the leadership of their own headmen toambush occasional bands of Pathet Lao and to defend theirvillages, but during the early 1950s the French/Laoforces set up a multi-ethnic garrison at Moos Plais, withten French officers led by a colonel. Lao officers andtechnicians were also stationed there, as were troopsfrom other mountain peoples in addition to Hmong. Helicoptersbegan to come with increasing frequency.An airstripwas built, shortening the trip from Luang Prabangto a few minutes. Eventually the Lao and French officersat Moos Plais were replaced by Hmong under the commandof General yang Pao, and the garrison was suppliedby American pilots.The third major indication of the Laos adaptivestage was in the establishment of a Lao school in Moos21

10 THE HMONG IN TRANSITIONPlais. This provided only two years of education, butfor the first time almost all of the boys and many of thegirls began to learn the rudiments of reading and writingLao, together with a little arithmetic and Lao civics. Asmall number of boys who showed aptitude and were otherwisesuitable then went to live with Lao contacts orfriends in nearby Lao towns to continue their education.The Laos Resettlement StageSome of the older men from Moos Plais now living inthe Twin Cities look back on the late period of the Laostraditional stage and the Laos adaptive stage as theirgolden age. They were prosperous; they sensed progressand change, but they were able to cope; they had a senseof accomplishment and of power.But by about 19673 the military garrison at MoosPlais was forced to withdraw, and most of the villagers(about 160 people) went with them. They left everythingthey could not carry or lead. After a day's walk theyreached Mom Phuv, a large Hmong village south of MoosPlais, which also had a military garrison and an airstrip.Their military garrison from Moos Plais joinedthat of Mom Phuv, and the civilians camped in tents suppliedby the military. They were completely dependent;all of their food was airlifted in.Thus began, on a small scale for these Hmong fromMoos Plais, the Laos resettlement stage. Other refugeesfrom nearby areas joined them, fleeing their own villages.Their settlement was a small example of whatAjchenbaum and Hassoun (1979) have called an "agglomerationde guerre," and what I will call a conglomeration.It was characterized by the intermingling of Hmong groupswho themselves did not know each other, in the same communitywith still other different ethnic groups (Khmu',Mien, Thai Dam, Lao). The military provided what overallorganization there was. In this particular case therainy season, the uncertainty about the future and thedagger made farming and other normal economic activityimpassible, so that all food and other supplies wereflown in.In scarcely two months the whole Mom Phuv conglomerationhad to move on again as the military situation oncemore became impossible and the combined garrison with-22

STAGES OF HMONG CULTURAL ADAPTATION 11drew. Their move formed a new conglomeration at TriosTub, another Hmong village with a garrison strategicallylocated in the mountains above the confluence of the NamOu (Lao: Ou River) with the Mekong, only twenty milesnorth of Luang Prabang. This conglomeration lasted sixmonths, during which time it was regularly surrounded byheavy fighting and suffered many casualties. Its numberscontinued to be swelled by more diverse groups whichjoined as they fled their earlier settlements and conglomerations.Finally, the civilians were flown out of Toos Tub toa safer destination, leaving the military forces to helpdefend Luang Prabang. They settled along the Nam Poui(Lao: Poui River), in an area that was across the MekongRiver from Moos Plais, toward the Thai border and aboutthirty miles southwest of the provincial capital ofSayaboury.4 The people flown in from Toos Tub joined asmall population of Lao and Hmong already in the area,which had not been appreciably affected by the war.Through further influx of displaced people, the populationin this new conglomeration eventually increased toeight thousand or nine thousand.Nam Poui was more systematically and more permanentlybuilt than the previous conglomerations in which itsnew residents had settled. Lao and United States aid officialslaid out the town in blocks.5 People from differentethnic groups lived in different parts of town.Within the Hmong section, the people originally from MoosPlais lived together and preserved the social structuresthey brought with them, under the same family and villageleaders.United States aid provided some animals for breedingand seed to plant both irrigated and mountain ricefields. Within a few months the people were growingtheir own food and were beginning to develop cash produce,primarily in pigs. The government and the Americanaid program extended a road into the community, helped inthe devel pment of irrigated lands and built publicbuildings, including a school. Lao, Chinese and Indianmerchants built stores and moved in.In many important ways the conglomeration at NamPoui was very different from the constricted and badlyoverpopulated larger conglomerations such as Long Cheng,in the heart of the war zone. Nam Poui had a similar23

12 THE HMONG IN TRANSITIONmixture of population (without the resident Americans)and a similar dominant military umbrella, but stresslevels were lower, and it became economically self-suff i-dent. Ultimately it did not have to be supplied withfood by the government, and it began to prosper.In terms of adaptation, Nam Poui shared with theother semipermanent conglomerations an increased exposureto nontraditional technology and material goods, greateropportunity for Lao education of the children, significantinteraction with non-Hmong, and an overarching politicalstructure which was supplied by the military, butwhich allowed traditional village and family structures(when they were still intact) to operate on a lower level.In this mixed environment, spurred by the needs createdthrough displacement, many Hmong rapidly learnedthings and became used to conditions they had never knownbefore.Nam Poui was settled about 1968. In 1975, someweeks after General Vang Pao left Laos, most of the conglomerationof Nam Poui left en masse for Thailand. Thecaravan of several thousand people crossed the border,was disarmed by the Thai, and was resettled in a locationthat became the camp called Sop Tuang.The Thailand Camp StageAt Sop Tuang, life was in some respects a continuationof the Nam Poui conglomeration. Most of the originalrefugees moved in together, and as they built SopTuang, they followed the organizational patterns they hadbeen using at Nam Poui. The same Hmong major who hadbeen in charge of the garrison at Nam Poui and who hadbeen the overall leader of the conglomeration was alsothe Hmong person in charge here under the Thai authorities.The same settlement by ethnic groups took place.These ethnic groups continued to be organized under theleadership each had brought with it. New refugee groupswere added from time to time, as had happened in NamPoui. They came as villages or other sizable, previouslyexisting groupsnot as individuals, small family groupsor parts of families.What was different about Sop Tuang, as compared toNam Poui, was that now the groups had constraints resultingfrom their status as refugees in a different country.2404:.;.4

STAGES OF HMONG CULTURAL ADAPTATION 13Placed above the social structure imported from Nam Pouiwas a level of authority responsible to the Thai government.A Thai military officer presided over the camp,and Thai soldiers were stationed there.Furthermore, in Nam Poui the Lao and United Statesgovernments had provided money, goods and personnel tohelp lay out and build the community and get the peoplestarted. But the people of the conglomeration had beenable to outgrow the need for extensive economic help. AtSop Tuang, after an initial period of inaction, the Thaigovernment, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees,and numerous religious and charitable agenciesgathered to provide food, medical care, education, sanitation,opportunities for economic development and essentialsupplies of material goods. Here was a loosely-knitgroup of organizations, sometimes cooperating, often competing,which the refugees had to learn to depend on forsurvival.The most significant difference from Nam Poui, sofar as the people were concerned, was that there was insufficienteconomic opportunity for them. Some men wereable to take advantage of the limited opportunities foremployment within and outside of camp, and women couldsell their handiwork to some extent,b but neither endeavorwas adequate to solve financial needs.The experience of the villagers from Moos Plais atCamp Sop Tuang was in several important ways differentalso from that of Hmong in the much larger, more denselysettled and more important camp of Ban Vinai. Refugeeswho arrived at Ban Vinai tended to come in small clusters,accompanied by only fragments of their socialgroupings. Unlike those at Sop Tuang, they often had totravel through Pathet Lao areas, had to hide out in thejungle for long periods, started out malnourished andarrived starving. They had to break up into small groupsto avoid detection, and many groups and individuals whoheaded for that part of Thailand never did arrive. Whenpeople did reach Ban Vinai there may have been members oftheir social groups already there, but the newcomers hadto take whatever housing location was available, andcould not live in groupings to which they were accustomed.So the lower rungs of leadership that existed underthe top levels of Thai control and the formal organiza-25

2614 THE HMONG IN TRANSITIONtion of Ban Vinai, were set up somewhat differently fromthose at Sop Tuang. Both camps were divided into sectors.In Sop Tuang the sectors were natural ones (interms of preexistent groupings) with people clustered insomewhat familiar ways.' In Ban Vinai people belonged towhatever sector they happened to be assigned housing in.8As families or villages were reunited at Ban Vinai, theydid, of course, reestablish older relationships, and aconsiderable part of the informal structure of the campwas made up of such groups in spite of their scatteredresidence. The formal structure, however, did not matchthe informal structure as well as they matched at SopTuang. An important related difference between Sop Tuangand Ban Vinai was in the part played by the educatedyouth at Ban Vinai. In the years immediately precedingthe initial evacuation of 1975, there had been about sixhundred Hmong students in Vientiane. They had formed astudent association as a mutual assistance group. Asthey evacuated to Thailand and eventually ended up in BanVinai they were very important in organizing and runningsome of the necessary functions of camp life. They assistedin food distribution, camp cleanup and sanitation,and they took over education of the children, as well asEnglish classes for everyone.It seems that they were in a strategic place for tworeasons: their education better prepared them for sonicaspects of this new situation, and the shredded socialstructures perhaps left a vacuum in leadership and potentialfor action on some levels of camp life. In BanVinai, as at Sop Tuang, the Hmong military provided theleadership at the top. Below that, in Ban Vinai, thefunctions served by the youth group were eventuallyabsorbed into the more formal structure of the camp or,in the case of education, were taken over by the Thai.Furthermore, the contribution was temporary because theeducated youth often went on to other countries soonerthan many others. But for a while they were critical tothe functioning of the camp.9At Sop Tuang, on the other ;land, the youth as agroup were of little importance in the operation of thecamp. They occupied a much more traditional relationshipto the community, I am : ,igesting, because community patternshad not been shredded in the migration, and alsobecause there was not as large a nucleus of students moreacculturated than their eiders as there was at Ban Vinai.

STAGES OF HMONG CULTURAL ADAPTATION 15The United States Resettlement StageThe only aspect of the United States resettlementstage on which I'll take time to comment is one regardingthe evolution of the role of the youth at Ban Vinai. Itis the difference in Hmong leadership and social organizationbetween Dallas-Fort Worth, Texas, and Minneapolis-St. Paul, Minnesota, reported by Mason and Downing (Mason1983; Downing 1983). In Dallas-Fort Worth, a strongyouth group operating under young leadership performsadaptive and supportive functions somewhat parallel tothose carried out by the youth groups of Vientiane, NamPhong and Ban Vinai. There is no mutual assistance associationcontrolled by elders. In the Twin Cities ofMinneapolis-St. Paul, however, although some of the leadersof the same group which was active in the camp arepresent, there is no significant youth leadership for theHmong community. Instead, the primary leadership comesfrom a variety of older types, including the former militaryand former people of influence in Laos, as well aspeople emerging in the American situation.As for the people of Moos Plais who are now in theTwin Cities, certain aspects of the social structurewhich they maintained throughout moves to Mom Phuv, ToosTub, Nam Poui and Sop Tuang still govern their relationshipshere. This is supplemented by tenuous ties to theLao Family Community and its network of relationships,all under the umbrella of an American system about whichthe people of Moos Plais are learning, but still understandvery little.TYPICAL INNOVATIONS OF THE STAGESHere follows, then, a sketchy list of the innovationswhich I see as being characteristic of the stages.I do not know much about the Laos penetration stage, butpresumably those Hmong who knew an outside language spokea Chinese language or Vietnamese, depending on where theycame from. They were small in number, kept much to themselves,and had infrequent contacts with the Lao orFrench.10In the Laos traditional stage Hmong had establishedtrade patterns with Haw, Lao and Chinese traders who came,,27

16 THE HMONG IM TRANSITIONto their villages, but there was minimal travel to Laotowns, minimal learning of the Lao language, and minimalcontact with the Lao/French military and government. Thecontact they did have included paying tribute that consistedof mountain and jungle products (Yang 1975:45).Yang Dao reports that the first low-level diet. ct officer(tasseng) was appointed as early as 1896, although itwas not until much later that this practice became wide-Hmong numbers, however, were increasing rapidly,spread.and some Hmong did experience some severe conflicts withthe French/Lao, notably the revo:e. of 1919 to 1921.Hmong cultivation of the poppy for the opium trade becameeconomically very important in the country.In the Laos adaptive stage, major changes, whichsignificantly began to alter the position and role of atleast some Hmong in Laos, took place. The Hmong presencenow became very noticeable as they traveled in groups toLao provincial centers to trade, becoming regular vendorsin the markets (Yang 1975:122-127), and as some of thembegan to live closer to these Lao towns. The provincialcapital of Xieng Khouang became an important Hmong c'ter. The establishment of Lao schools in Hmong villages'',and the practice of sending a few Hmong studentsto Lao towns to study, began in this period. Virtuallyall Hmong men now spoke some Lao, and Lao vocabulary borrowingslaced Hmong discourse. A few Hmong went toFrance to study, and a tiny educated Hmong elite began toemerge.A national Hmong leadership was epitomized at firstwith Touby Lyfoung, who became officially recognized asleader of the Hmong by the French/Lao goverment in 1947(Yang 1975:51), and by his rival Faydang Lobliayao, wholed the communist faction (Yang 1975:54). Later therewere Yang Pao and others. During this period the cooperationwith the French/Lao military and civilian authoritiesbecame strong among some of the noncommunist Hmong,and a sense of participation in the Lao state began toemerge. Hmong district heads (tasseng) were now frequentlyappointed.Christianity, both in Roman Catholic and in Protestantforms, made solid headway for the first time amongthe Hmong in Laos during this stage. Missionary effortshad existed long before that, but for some Hmong, conversionto Christianity now became a desirable option28

STAGES OF HMONG CULTURAL ADAPTATION 17(Barney 1957a,b).Some Hmong also began to make use of Western medicineas administered in Lao hospitals to a much greaterdegree than before, although Western medicalstill treatmenttended to be a solution of last resort, andqualitytheof the medical treatment available was not good(Dooley 1958:192ff; Halpern 1961).In the Laos resettlement stage, modern war came tolarge apercentage of the Hmong population in Laos withcruel force and disruption. The Hmong participation inthe war became intense. Hmong suffered terrible casualties,many villages being uprooted, some several times;and large parts of the population were resettled in ref u-gee conglomerations, often around military centers.12Normal agricultural and economic activity were often impossibleon any adequate scale, and in many of the centersHmong were forced to live by external aid plus whatevernew economic skills they could learn. Traditionalsewing skills were adapted to make items directly salableto Westerners.13For many Hmong, war and conglomerate life broughtparticipation in some forms of modern technology. Instrumentsof warand in some areas, those of transportationand agriculturebecame more widely known.tary Mili-participation and life in the conglomerationsbrought new social structures that overlaid thetionaltradi-ones still in place. Many military learned anEnglish-based code for communication with American officersand civilian pilots, while some Hmong learned tocommunicate in everyday English.-Westernization and adaptation to Lao culture wasintensified for some Hmong as they participated with Laoand Americans in the war effort, lived in the same conglomerationswith Lao and other ethnic groups, and in afew cas,ss became more educated in Lao.Hmong literacy increased slightly. In addition tothe rnmanized orthograthy, two Lao-based writing systemswere in use during the period. One was developed by theHmong who sided with theparts Pathet Lao and the otherof bythe Protestant church (Smalley 1976; Lemoine1972a). As economic and cultural deprivationtaryand mili-stress increased, there developed the Chao"Lord of the Sky") MessianicFa (Lao:movement, an attempt to recreatea golden past mixed with elements of the changingpresent, something which was uniquely Hmong. With it was. .t40On

18 THE HMONG IN TRANSITIONinvented a writing system unlike any of the others in usefor the language (Lemoine 1972a:142-146).The Thailand camp stage was in many ways an extensionof the conglomerate life of the resettlement areasin Laos. There were some important differences, ofcourse. Camp life brought contact with a different governmentand numerous foreign agencies. It brought artificialrestriction on movement, and even more limitedpossibilities for economic self-help. It also broughtsome relief from war pressures, although the pressurecontinued for those Hmong who slipped back across theborder to continue fighting or who had relatives in dangerin Laos.The degree to which traditional social structureswere shredded in camp life depended on the family historyof disaster. Some camps preserved the spatial proximityof traditional relationships from earlier village settlement.Ban Vinai in particular did not. For many Hmongthe camps brought the trauma of family separation of anew kind. Parts of extended families would leave totravel unimaginable distances to fearful and legendarydestinations in other parts of the world.The camps brought Thai education for children, andintensified aesire and opportunity for Hmong literacy.It also brought high motivation and increased opportunityfor learning English. Yang Dao (personal communication)states that at Nam Phong, the Thai camp to which- thefirst Hmong refugees were taken, there was an Englishclass taught by the few who knew some English "underevery tree."- Eventually some of this adult education wastaken over by social agencies from outside the camp.The Hmong who came to the United States, then, camewith a far more varied and complex experience than areading of Lemoine (1972b), set in the Lao adaptivestage, or Geddes (1976), set in an analogous stage inThailand, would lead us to expect. Some people had beenswept along by the changing events, without learning todo much more than minimal coping for survival. Othershad responded to the new situations by learning newskills and adapting creatively to new opportunities.The innovations of the United States resettlementstage are beyond the scope of this paper, even if theywere to be presented only in the sketchy form with whichI approached the other stages. But for many Hmong this30

STAGES OF HMONG CULTURAL ADAPTATION 19has been the most traumatic stage of all. This is thestage, of course, in which many Americans have come toknow the Hmong. The attempt to understand something ofwhat is behind the adaptations emerging in the UnitedStates requires us to look at the innovations which tookplace in the camps and, before that, in the resettlementconglomerations, in addition to examining traditionallife. Adaptation to life in America continues the processwhich has been going on through the lifetimes of theHmong who are here.ACKNOWL<strong>ED</strong>GEMENTSThis work was aided by National Endowment for theHumanities grant #R0-20310-82 to the Southeast AsianRefugee Studies program of the University of Minnesota.I have profited by comments on an earlier draft fromBruce Downing, Lysao Lyfoung, Vang Vang and Yang Dao.NOTESII am here concerned only with modern history of theHmong, and only with developments which took place inLaos and among Hmong who were dispersed from Laos since1975. The centuries-long experience of the Hmong inChina is not included.2This is probably a Hmong pronunciation of the Lao MuongMai. The Hmong name is Zos Key Xov Hlau. The villageswere located about one third of the way between MuongSai and Muong Ngoi. Principal informant on theexperience of the Moos Plais people was Vam NtxhaisXyooj (Vas Say Xiong), headman of one of the villagesthroughout the total experienced described. His informationwas supplemented by that provided by other membersof the group.3This date is estimated by working back from Vam NtxhaisXyooj's memory of approximate times spent in subsequentlocations.4A move of about one hundred direct-line miles.31

20 THE HMONG IN TRANSITION5Note that rectangular blocks and houses oriented to themare not in keeping with traditional Hmong houseorientationpatterns.6Doris White lock reported (personal communication) thatat nearby camp Ban Nam Vac:, men sometimes worked withwomen at the embroidery and became fairly good at it.7"The constraint of space, so common in the other refugeecamps, is not a problem in Sop Tuang. The camp isspread over approximately 1,000 acres .... [This has]allowed the residents to group themselves into naturalvillage communities." (Committee for Coordination1982:52).81 have not had time to find out how conglomerations likeLong Cheng were organized, and whether (as I suspect)some of that organization carried over into the camps.9lnformation about Ban Vinai and the youth group there isprimarily from Yang Vang, who was one of the youths involved.10For a map of nineteenth century Hmong migration intoLaos, see Yang 1975:10.11 Yang Dao reports that the first such school in XiengKhouang Province was established in 1939 (1975:134).12For an indication of the distribution of Hmong resettlementareas in southern Xieng Khouang Province in 1974,see Yang 1975:144.13The square or oblong pi ntaub decorative pieces sold byHmong women in the United States date back to 1964, duringthe resettlement stage in Vientiane. The sewingFoil Is are very much older, of course, as are most of.he designs typically to be seen in examples of thiscraft. However, the square form was adapted for sale totourists out of the traditional baby carrier shaped tohold the baby on the mother's back, and with strapsattached (Lemoine, personal communication).32

STAGES OF HMONG CULTURAL ADAPTATION 21REFERENCESAjchenbaum, Yves, and Jean-Pierre Hassoun. 1979. Histoiresd'insertion de groupes familiaux Hmong reen France. Association pour le Developpement dela Recherche et !'Experimentation en Sciences Humaines.Barney, G. Linwood. 1957a. "The Meo--An IncipientChurch." Practical Anthropology 4.2:31-50.. 1957b. "Christianity: Innovation in Meo Culture."Unpublished MA Thesis, University of Minnesota.Committee for Coordination of Services to Displaced Personsin Thailand. 1982. The CCSDPT Handbook: RefugeeServices in Thailand. Bangkok: du MaurierAssociates.Dooley, Tom. 1958. The Edge of Tomorrow. New York:Farrar, Straus and Cudahy.Downing, Bruce (assisted by Bruce Thowpaou Bliatout).1983. "The Hmong Resettlement Study Site Report:Dallas-Fort Worth, Texas." (Draft prepared in theSoutheast Asian Refugee Studies Program of the Universityof Minnesota.)Geddes, William R. 1976. Migrants of the Mountains: TheCultural Ecology of the Blue Miao (Hmong Njua) ofThailand. Oxford: Clarendon Press.Halpern, Joel. 1961. "Laotian Health Statistics." LaosProject Paper No. 10. Mimeographed.Lemoine, Jacques. 1972a. "Les ecritures des Hmong."Bulletin des Amis du Royaume Lao 7-8:123-165.. 1972b. Un village Hmong vert du haut Laos.Paris: Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique.Mason, Sarah. 1983. "The Hmong Student Association ofDallas and Fort Worth". In "The Hmong Resettlement33

22 THE HMONG IN TRANSITIONStudy Site Report," edited by Bruce Downing (seeabove).Smalley, William A. 1976. "The Problems of Consonantsand Tone: Hmong (Meo, Miao)." In Phonemes andOrthography: Language Planning in Ten Minority Languagesof Thailand, edited by William A. Smalley,pp. 85-123. Canberra, Australia: Lingustic Circle ofCanberra.Yang Dao. 1975 Les Hmong du Laos face au develloppement.Vientiane, Laos: Edition Siaosavath.34

THE HMONG OF LAOS:ECONOMIC FACTORS IN REFUGEE EXODUS AND RETURNRobert Cooper*INTRODUCTORY NOTEThis paper is concerned only with the economic aspectsof Hmong exodus from and repatriation to Laos. Itis not suggested that economic motives for fleeing an intolerablesituation preclude or dominate other motives.That the great majority of Hmong refugees fled because ofa genuinely-felt fear of reprisal or persecution from thenew regime is not called into question. I suggest onlythat there were additional economic reasons for the Hmongto leave Laos, and to leave when they did. These economicfactors in the Hmong exodus are important (or arelikely to become important) to any discussion of futurereturn to Laos, however and under whatever political ormilitary conditions that return is envisaged.I am fully aware that the suggestion that economicfactors played a role in the Hmong refugee exodus, albeita subordinate role, will transgress some Hmong sensitivities.I hope that my Hmong friends, on both sides of thefrontier, will understand that my intention in makingthis suggestion is only to contribute to the debate onthe future welfare of all Hmong, particularly those currentlycaught up in the no man's land of refugee camps.Naively, I ask the Hmong reader to set aside the intoleranceand suspicion bred through years of tragedy anduncertainty and to approach this paper with as much as heor she can muster of the tolerance and sincerity thatcharacterizes traditional, peaceful, village Hmongety.soci-THE THESISSo far, 190 Hmong have repatriated voluntarily toLaos since the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees(UNHCR) began a voluntary repatriation programme in1980 (see Table 1; all figures are correct as of end of1983).2335

24 THE HMONG IN TRANSIT1011Table 1VOLUNTARY REPATRIATION TO LAOSYear Lao Hmong Yao1980 1931981 276 130 1331982 802 59 2081983 526 1 801,797 190 421 TOTAL: 2,408Not very many. But the importance of the programmecannot be judged simply by the numbers involved. A greatmany more Hmong are at this moment (January 1984) sittingit out in refugee camps in Thailand, waiting to see whathappens to the 190 before deciding which way to go: onto America or back to Laos.One-hundred-ninety people is, if you put them alltogether, only the size of one Hmong village, and not avery big one at that. One-hundred-ninety returnees comparedto more than 60,000 Hmong who have chosen resettlementin third countries; 190 returnees compared to morethan 40,000 Hmong currently in the camps; 190 returneescompared to more than 100,000 Hmong who have fled the LaoPeoples Democratic Republic.And 190 returnees comparedto an estimated 200,000 Hmong remaining in the country.The number of Hmong who have decided to turn aroundand go back home is tiny, yet the movement back to Laoshas a significance far greater that its size. Their decisionto return poses questions which must be answered.36

THE HMONG IN LAOS: ECONOMIC FACTORS 25Why did Hmong leave Laos? Why did the exodus takethe apparently erratic form evident in the annual andmonthly statistics? (Tables 2 and 3). Why are there suchremarkable differences between departure patterns of lowlandLao and highland Hmong (Table 2, 3 and 4). Why didthe majority of Hmong remain in Laos? Why did some Hmong,having left, decide to return to Laos?Reference to political, factors alone cannot fullyanswer these questions or fully explain patterns of behaviour.I am going to suggest that by adding an economictheory to the well-known political facts, we can comenearer to an explanation.In this paper, I shall argue that the environmentthat supported traditional Hmong swidden (slash-and-burn)cultivation in Laos had ganged significantly before thegreat exodus of 1975, and that because of this changemany of those who fled at that time might have died ofhunger had they remained in Laos. I shall also considerthe possibility that the very magnitude of the exodus reestablishedsomething of an ecological equilibrium, furtherreducing the urgency of the exodus rate and raisingthe possibility that resources in Laos could support amovement of Hmong refugee farmers back to the mountainsof Laos.I am also going to suggest that Hmong who chose toleave Laos early in the year probably had sound economicmotives, in addition to any other motives, for going atjust that time.I find it convenient to arrange evidence and argumentsto test the following thesis:In Laos, a direct correlation exists between theHmong population/resources ratio and the rate ofexodus and return.I shall consider evidence to support this thesiswithin three categories: historical, observational andempirical.37

Table 2ARRIVALS IN THAILAND BY YEAR1975 1976 1977 19711 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983LAO10,195 19,499111,065 48,786 22,045 28,96716,4283,2034,521HILL-TRIBE44,659 7,2663,873 1,013 23,943 14,9014,3051,8162,870Table 3ARRIVALS IN THAILAND BY MONTHA. HILL-TRIBE'Year San Feb Mar Apr May Jun 3u1 Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec TOTAL19816514031,221662358228 5628415114241454,30519821321713713191910 416216412710817816191323559323934017119 35420601121142202,870B.LOWLAND LAO19816514031,221662358228 5623415114241454,3051982643612423196189227 21525079120961483,2033ri

THE HMONG IN LAOS: ECONOMIC FACTORS 27THE HISTORICAL EVIDENC<strong>ED</strong>uring the years 1850 tofought a 1880, the Hmong in series Chinaof wars against the Manchu Government,which was at the time committed to a policyation in order to of heavy tax-pay off the heavy indemnities by the British after demandedthe Opium War andways of making money.was looking forOpium had caused theseand it seems likely indemnitiesthat the Manchusof paying off saw opium as a waythese indemnities. Certainlypolicy of banning opiumthe Chinesecultivation was now reversedproduction seems to have andbeen encouraged.sittingWith the Hmongon some of the best opium land inis logicalthe world, itto assume that thetime wanted Chinese authorities ofcontroltheover it and revenue from it.seems reasonable therefore Itto say that the Hmong-Manchuwars were predominantly economic in character.To say that the wars had economic motives doesof course, deny that not,there was repression by the Manchuauthorities or that manythe thousands of Hmong fledborder. acrossFor all we know, the nineteenth centuryHmong exodus from China could have beengreat as the twentieth every bit ascentury exodus from Laos.even greater.PerhapsOf course, repressionin spite of was not absolute andthe great number of refugees who fledcountry, the themajority of Hmong remained incentury China, as the majoritynineteenthof Hmong remained intieth century Laos.twen-Thus, the history of the Hmong isleast seen to contain atone precedent of large-scale refugee exodus.Hmong, unable Theto continue their way of lifeterferencewithout in-from the Chinese authorities, fled innumbers from one nationlargestate to re-establishsuccessfully in anotherthemselvesnation state.This nineteenth century refugee movementonce persecution,slowed downor the fear ofexist.persecution, ceasedHowever,tothe movement did notdid it reverse.stop. Still lessSignificantly, it continued. Why?I can see only one reason to explain the persistentmovement from China, throughand into Laos: the the northern part of Vietnameconomic certainty thatmuch better in theresources werenew location than in China.It seems likely that a situation ofimbalance or, to callenvironmentalit by another name, "resource scar-39

78THE HMONG IN TRANSITIONwith the French, this was only after the rn' 'ion wasunder way. Anyway, the Hmong in Laos probably extractedfrom the French a much greater degree of political autonomythan they could hope to obtain in Thailand.city," existed in some of the Hmong areas of nineteenthcentury southern China and that the Hmong solved thisproblem by relocating a large number of their people intoan area of fresh resources. Once ar 'vironmental balancewas reestablished in China, or the imbalancebecame less acute, the exodus slowed t r,As far as an be guessed, the 0,ation from Chinaseems to have taken two forms: a large-scale refugee exodusand a small-scale calculated relocation of individualfamilies or groups of families.Exactly the same forms of migration are evident inthe post-1975 Hmong exodus from Laos. This fact in itselfsuggests a likely similarity of causes, which Iwould summarize as fear of persecution plus the need toescape a situation of resource scarcity.By suggesting the existence of historical precedent,I do not wish to imply that the Hmong collectively orindividually copied actions which had proven effectiveresponses to problems encountered in the past. I am onlysaying that the Hmong have demonstrated an ability toface economic and political problems in a certain way,that way being large-scale migration.After the exodus from China into Vietnam and Laos, afurther movement of Hmong took place from Laos into Thailand.This gradual migration took the form of householdrelocation. It seems to have begun soon after the Hmongleft China and to have led to a sizable Hmong presence inThailand by the early twentieth century. Why did thismovement take place?A politica! motive seems to have been absent. Althoughthe Hmong in Laos did get into some skirmishes40

THE HMONG IN LAOS: ECONOMIC FACTORS 29I would suggest, therefore, the likelihood that theswidden use of mountain sides for opium cultivation(which progressively reduces soil fertility until landceases to be productive) created a resources/populationimbalance in certain Hmong areas of Laos throughout thefirst half of the twentieth century and that the Hmongresponded to that situation in exactly the same way theyhad responded to the same problem in China: by moving aproportion of the populationnot all of the populationinto a situation of resource plenty.Thus, it can be argued that two historical precedentsof Hmong economic migration across national frontierspreaated the beginnings of the Laotian civil war inthe 1950s.The thirty-year-long civil war was undoubtedly responsiblefor removing further portions of land in Hmongareas of Laos from the possibility of exploitation. Manymountain areas, previously open to cultivation, werestripped of vegetation by the effects of bombing and chemicals.During the fighting of the 1960s and early 1970s,the Hmong tended to group in certain safe villages, indisplaced person camps in the lowlands and in the "secretarmy" mountain town of Long Cheng, which had been establishedas early as 1961. Such large population groupingscould not hope to supply all subsistence needs by traditionalswidden cultivation, and a great many Hmong familiescame to rely increasingly on food drops by aircraft,handouts in the population centres or the soldier's payearned by adult males. Most estimates of the number ofHmong on some form of "welfare" during this period totalover one hundred thousand.In addition to these one hundred thousand we shouldremember that there were also Hmong in uniform on thePathet Lao side. They earned little money but it is trueto say that they also gained at least part of their basicsubsistence by nonagricultural means.The picture of Hmong areas of Laos in 1975 is one inwhich the pinch of resource scarcity had long promoted asteady movement of Hmong migrants into Thailand; thissituation of resource scarcity was compounded by a civilwar which had many of the effects of the industrial revolutionin Europe, driving farmers from their lands whilst41

30 THE HMONG IN TRANSITIONat the same time offering alternative means of livelihoodin centres of population.It is also worth noting that as far as we know comparativelyfew Hmong fled war-torn Laos in the decade before1975. This is surprisingeven amazingconsideringthat the Hmong were the principal casualties of the war.This low level of refugee outflow during the war suggestsone or both of two things: either that the Hmong stayedin Laos to fight against communism or that the provisionof aid and paid employment acted as an economic incentiveto remain, even when remaining was not only dangerous butrequired adaptation or abandonment of traditional lifestyle.(Similar economic incentives induced many thousandThais to leave the safety of Thailand and fight asmercenaries in Laos.)When, in 1975, the alternative means of livelihoodcame to an abrupt end, tens of thousands of Hmong foundthemselves abruptly face to face not only with the fearof the enemy's revenge but also with a situation of accumulatedresource scarcity.I do not doubt that the Hmong who fled Laos at thattime did so from a genuine fear of persecution followingthe change in regime. However, I feel it is worth makingthe point that they also had an economic motive for fleeingwhen they did. Had they remained in Laos, it is difficultto see how they could have avoided large-scalefamine. Certainly the Pathet Lao government, had it beeninclined to do so, could not have offered any assistance,since the rice harvests in the years following the changeof regimes were insufficient to feed the lowland population.Thus, whatever the political reasons for leaving(which are not in doubt), the convulsive exodus from Laoscould be said to have served economic functions, both forthe leavers and the stayers. The leavers were removedfrom a situation of resource scarcity and potential faminewhilst the stayers had far less competition foravailable resources.THE OBSERVATIONAL EVIDENCEMy argument that the Hmong of Laos suffered from avery adverse population/resources imbalance is supported42

THE HMONG IN LAOS: ECONOMIC FACTORS 31by my personal observations made over the period of December1980 to March 1983. During this time, I lived inVientiane and travelled very widely by aeroplane, helicopter,truck, jeep and boat, and on foot. During thesetravels around the country I was able to visit Sayaboury,Xieng Khouang, Luang Prabang, Vientiane, Savannakhet,Pakse and Attopeu provinces and got to see a number ofHmong villages.I was particularly interested in Xieng Khouang forfour reasons:1. The majority of Hmong refugees in Ban Vinai Camp (theHmong refugee camp in Thailand) seem to come fromthat province.2. Only one of the 190 Hmong repatriates to Laos returnedto Xieng Khouang. A few others had originatedfrom that province but chose not to return there.3. Many of some if teen hundred Hmong who live in thelarge settlement at KM 52 north of the town ofVientiane said sy had left Xieng Khouang becauseof the difficulty of finding enough land to farm inthat province.4. Several thousand Hmong from Xieng Khouang had resettledin several groups around Yang Viang. Some hadarrived there before 1975, but most had come sincethe change in regimes. All of those I met statedthat it wrl very difficult to make a living in XiengKhouang.I was able to fly extensively by helicopter throughoutXieng Khouang Province. Everywhere, the mountainswere covered with grassnot trees. And it was the kindof tough grass known technically as imperata, a grassthat grows where little else can and puts down long rootswhich make cultivation by hand hoe extremely difficult ifnot impossible.I had flown around northern Thailand ten years previouslyand seen much the same kind of thing in areas ofknown resource scarcity. However, even in the worstareas of northern Thailand, it had still been possible tosee some trees and some secondary growth on the mountain-31 43

32 THE HMONG IN TRANSITIONsides and there was the feeling that resources recoverywas at least possible. Throughout most of Xieng Khouang,however, I could find trees only in the folds betweenmountains, where the slope was usually too steep to permitcultivation.I did see Hmong villages and fields but far fewerthan I had expected to see. There were, by contrast,many Hmong in Phone Savane, the capital of Xieng KhouangProvince, including the president of the province. I wasable to speak with them without restriction and all gavea rather gloomy picture of the province's economy. Theiraccounts suggest that it is still possible for some villagesto get by by growing opium, and Xieng Khouangmains the major opium - producing province of Laos, but"getting by" means living next to poverty and, as thingsstand, there is no reason to assume that agriculturalprospects in the province will improve very much in thefutureṪhe situation in Luang Prabang, Sayaboury, and Vientianeprovinces was less severe than in Xieng Khouang.Several villages I visited seemed to be getting by reasonablywell in terms of fields cultivated, food stocksheld, household livestock and standard of housing, dressand so on. However, there is certainly no cause for complacency.Even in the best of areas it would be verydifficult to find a single location containing adequateresources to support installation of a village-sizedgroup of, say, two hundred Hmong wishing to follow onlytraditional techniques of cultivation.Many other foreigners travelling to various parts ofLaos have confirmed my impression that the mountain areasof Laos, in spite of very low population ratios, sufferfrom a situation of resource scarcity that could best bedescribed as varying between serious and chronic. It is,I feel, most likely that the roots of this situation extendback far beyond the great divide of 1975.THE EMPIRICAL EVIDENCEThe empirical evidence to support the thesis of directcorrelation between resource availability and therate of exodus is, I must admit, not 100 percent convincing.This is mostly because of the difficulties involved44

THE HMONG IN LAOS: ECONOMIC FACTORS 33in doing any really objective research in Laos and in thecamps of Thailand. I have therefore had to rely on statisticscollected for various official reasons, none ofthem collected specifically to test the thesis. It mustalso be borne in mind that these figures represent onlymovement in and out of camps. It is most likely thatthousands more Hmong than get into the statistics havemoved across the border into Thailand without passingthrough a camp and equally likely that several thousandhave "spontaneously repatriated" to Laos.The figures I am giving here do not conclusivelyprove my thesis. On the other hand, they certainly donot disprove it. To play it safe, I would say that areasonable interpretation of available statistics tendsto support the thesis.First, annual arrivals of Hmong refugees in Thailandsince 1975, as set out in Table 2, invite analysis a-gainst an economic background. (Figures are actually forhill-tribe arrivals and include a few thousand Yao andsome members of other minority groups, but the great majorityare Hmong.)Two peaks are evident: 1975 and 1979. The reasonsfor the 1975 exodus are obvious enough: fear of retaliationagainst the Hmong by the victorious Pathet Lao andthe very sound economic reasons for leaving that I havealready gone into. But why should figures peak again in1979? If fear of such factors as "yellow rain" were theonly reason for leaving, why did 23,943 flee the countryin 1979 and only 1,816 in 1982? The real answer, I feel,has a lot to do with economics and the economic historyof the Hmong.For a long, long time Hmong have lived near larger,more dominant ethnic groups. Speaking as we must in generalizations:the majority ethnic groupsChinese, Vietnamese,Lao and Northern Thaiwere firmly entrenched inthe lowlands where they practiced irrigation methods togrow rice and lived in communities typified by permanenteconomies, permanent villages, permanent authority structuresand so on. The Hmong, on the other hand, werehopping around from mountaintop to mountaintop, practicingshifting cultivation in communities typified byshifting economies, temporary villages and temporary authoritystructures. During thousands of years of quietsubsistence farming, the Hmong lived near a majority cult45

34 THE HMONG IN TRANSITIONture but had little reason to interact with that cultureand experienced no real competition for available resources.Then, along came cash-crop opium.Starting sometime in the nineteenth century, theHmong began to specialize in opium. They continued topractice economic specialization even when this meantthat sufficient rice or other foods could not be grown tomeet all domestic needs. It was more profitable to sellthe opium and buy the extra food required, or to exchangeopium directly for food.A situation developed in which, although very fewHmong actually owned irrigated rice fields, a great manyHmongperhaps most Hmongwere dependent for at least apart of their basic food supply on lowland fields in Laohands. The Lao were, in turn, dependent on Hmong (andsome other hill-tribe groups) for opium. But it is possibleto live without opium, whereas it is much more difficultto live without rice, as was dearly evident inLaos in 1977 and 1978.In 1977, Laos experienced a disastrous drought.This was followed in 1978 by an even more disastrousflooding at harvest time. In both years Laos was forcedto appeal for international assistance to prevent famine.There was, of course, very little rice from any sourceavailable to sell to the Hmong.The effects of this economic situation on the exoduspattern of ethnic Lao is seen very clearly in Table 2.More left in 1978 than in any other year. For the Hmong,the effect was a little delayed for two reasons. Firstly,the Hmong upland rice crop, insufficient for allneeds as it was, was relatively unaffected by the floods.The October harvest therefore was enough to keep everybodygoing until after the January opium harvest of 1979.By that time, however, it would have been clear that sup-,plementary rice would not be available and it seems reasonableto assume that this has something to do with the1979 Hmong exodus peak.The years 1981, 1982 and 1983 have seen the bestrice harvests in Laos for many years. (Laos can now beconsidered self-sufficient in rice cultivation.) Thesegood harvests, like the bad, seem to be reflected in theannual exodus rate for both Hmong and Lao in 1982 and1983, which are the lowest recorded since 1975.'46

THE HMONG IN LAOS: ECONOMIC FACTORS 35A second economic reason for the delayed effect onHmong exodus patterns is suggested by the monthly figuresfor Hmong refugee arrivals in Thailand over the years1981, 1982 and 1983, which are set out in Table 3.(Monthly statistics are not available before January1981.)Figures for the first four months of each year aremuch higher than for the other months of each year andpeak around March in all three years. Why should thispattern emerge and what does it suggest?A facile explanation often heard and credited, isthat the Mekong River, which most Hmong must cross beforearriving in Thailand, is low during the first half of theyear and at its height towards year's end. If this factis to be used to explain the least number of hill-triberefugee crossings (only four) in November 1981, it cannotexplain the high figure of 1,413 lowland Lao who crossedthe same river in the same month of the same year.certainly Itcannot explain why no Hmong crossed in June1982, when the river was at its lowest.Thus, whilst it is recognized that the Mekong inflood presents a fearsome obstacle to mountain people unusedto water travel, we must look beyond the rivertheory for an explanation of the monthly patterns of exodusevident in Table 3. I suggest that these patternsare less a result of river level than they are evidenceof the dictates of the agricultural year.Hmong harvest rice around October, sometimes intoNovember. This harvest is followed by Hmong New Yearcelebrations, which in turn are followed by the opiumharvest.The opium harvest usually takes a single familythree to four weeks to complete. The precise date it beginsvaries between localities and depends on soil conditions,type of seeds used and weather conditions in anyparticular year. At the very earliest, it begins inearly December and at the very latest it is completed inthe first days of February. The two months following theopium harvest, February and March, are used to cut newfields, repair the house and do various tasks to preparefor the coming agricultural year. Families intending tomove to a new location do so at this time of year. They,,47