The diagnosis and clinical importance of Giardiasis

The diagnosis and clinical importance of Giardiasis

The diagnosis and clinical importance of Giardiasis

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

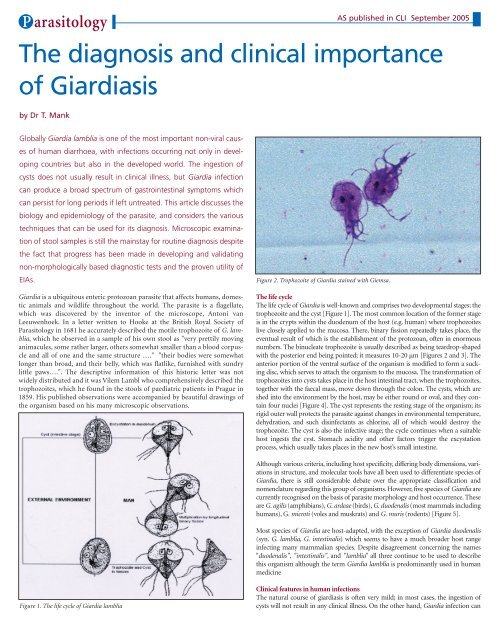

P arasitologyAS published in CLI September 2005<strong>The</strong> <strong>diagnosis</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>clinical</strong> <strong>importance</strong><strong>of</strong> <strong>Giardiasis</strong>by Dr T. MankGlobally Giardia lamblia is one <strong>of</strong> the most important non-viral causes<strong>of</strong> human diarrhoea, with infections occurring not only in developingcountries but also in the developed world. <strong>The</strong> ingestion <strong>of</strong>cysts does not usually result in <strong>clinical</strong> illness, but Giardia infectioncan produce a broad spectrum <strong>of</strong> gastrointestinal symptoms whichcan persist for long periods if left untreated. This article discusses thebiology <strong>and</strong> epidemiology <strong>of</strong> the parasite, <strong>and</strong> considers the varioustechniques that can be used for its <strong>diagnosis</strong>. Microscopic examination<strong>of</strong> stool samples is still the mainstay for routine <strong>diagnosis</strong> despitethe fact that progress has been made in developing <strong>and</strong> validatingnon-morphologically based diagnostic tests <strong>and</strong> the proven utility <strong>of</strong>EIAs.Giardia is a ubiquitous enteric protozoan parasite that affects humans, domesticanimals <strong>and</strong> wildlife throughout the world. <strong>The</strong> parasite is a flagellate,which was discovered by the inventor <strong>of</strong> the microscope, Antoni vanLeeuwenhoek. In a letter written to Hooke at the British Royal Society <strong>of</strong>Parasitology in 1681 he accurately described the motile trophozoite <strong>of</strong> G. lamblia,which he observed in a sample <strong>of</strong> his own stool as "very prettily movinganimacules, some rather larger, others somewhat smaller than a blood corpuscle<strong>and</strong> all <strong>of</strong> one <strong>and</strong> the same structure …." "their bodies were somewhatlonger than broad, <strong>and</strong> their belly, which was flatlike, furnished with sundrylittle paws….". <strong>The</strong> descriptive information <strong>of</strong> this historic letter was notwidely distributed <strong>and</strong> it was Vilem Lambl who comprehensively described thetrophozoites, which he found in the stools <strong>of</strong> paediatric patients in Prague in1859. His published observations were accompanied by beautiful drawings <strong>of</strong>the organism based on his many microscopic observations.Figure 2. Trophozoite <strong>of</strong> Giardia stained with Giemsa.<strong>The</strong> life cycle<strong>The</strong> life cycle <strong>of</strong> Giardia is well-known <strong>and</strong> comprises two developmental stages; thetrophozoite <strong>and</strong> the cyst [Figure 1]. <strong>The</strong> most common location <strong>of</strong> the former stageis in the crypts within the duodenum <strong>of</strong> the host (e.g. human) where trophozoiteslive closely applied to the mucosa. <strong>The</strong>re, binary fission repeatedly takes place, theeventual result <strong>of</strong> which is the establishment <strong>of</strong> the protozoan, <strong>of</strong>ten in enormousnumbers. <strong>The</strong> binucleate trophozoite is usually described as being teardrop-shapedwith the posterior end being pointed; it measures 10-20 µm [Figures 2 <strong>and</strong> 3]. <strong>The</strong>anterior portion <strong>of</strong> the ventral surface <strong>of</strong> the organism is modified to form a suckingdisc, which serves to attach the organism to the mucosa. <strong>The</strong> transformation <strong>of</strong>trophozoites into cysts takes place in the host intestinal tract, when the trophozoites,together with the faecal mass, move down through the colon. <strong>The</strong> cysts, which areshed into the environment by the host, may be either round or oval, <strong>and</strong> they containfour nuclei [Figure 4]. <strong>The</strong> cyst represents the resting stage <strong>of</strong> the organism; itsrigid outer wall protects the parasite against changes in environmental temperature,dehydration, <strong>and</strong> such disinfectants as chlorine, all <strong>of</strong> which would destroy thetrophozoite. <strong>The</strong> cyst is also the infective stage; the cycle continues when a suitablehost ingests the cyst. Stomach acidity <strong>and</strong> other factors trigger the excystationprocess, which usually takes places in the new host’s small intestine.Although various criteria, including host specificity, differing body dimensions, variationsin structure, <strong>and</strong> molecular tools have all been used to differentiate species <strong>of</strong>Giardia, there is still considerable debate over the appropriate classification <strong>and</strong>nomenclature regarding this group <strong>of</strong> organisms. However, five species <strong>of</strong> Giardia arecurrently recognised on the basis <strong>of</strong> parasite morphology <strong>and</strong> host occurrence. <strong>The</strong>seare G. agilis (amphibians), G. ardeae (birds), G. duodenalis (most mammals includinghumans), G.microti (voles <strong>and</strong> muskrats) <strong>and</strong> G. muris (rodents) [Figure 5].Most species <strong>of</strong> Giardia are host-adapted, with the exception <strong>of</strong> Giardia duodenalis(syn. G. lamblia, G. intestinalis) which seems to have a much broader host rangeinfecting many mammalian species. Despite disagreement concerning the names"duodenalis", "intestinalis", <strong>and</strong> "lamblia" all three continue to be used to describethis organism although the term Giardia lamblia is predominantly used in humanmedicineFigure 1. <strong>The</strong> life cycle <strong>of</strong> Giardia lambliaClinical features in human infections<strong>The</strong> natural course <strong>of</strong> giardiasis is <strong>of</strong>ten very mild; in most cases, the ingestion <strong>of</strong>cysts will not result in any <strong>clinical</strong> illness. On the other h<strong>and</strong>, Giardia infection can

P arasitologyAs published in CLI September 2005Figure 3. Scanning electron micrograph <strong>of</strong> a Giardia lambliatrophozoite from a biopsy <strong>of</strong> human jejunum.sometimes produce abroad spectrum <strong>of</strong> gastrointestinalsymptoms inaddition to diarrhoea.<strong>The</strong> <strong>clinical</strong> syndrome <strong>of</strong>acute giardiasis has beenwell characterised, especiallyin travellers. <strong>The</strong>most prominent symptom<strong>of</strong> the infection isprotracted diarrhoea. Itcan be mild <strong>and</strong> producesemisolid stools, or it canbe intensive <strong>and</strong> debilitatingwhen the stoolsbecome watery <strong>and</strong> voluminous.Untreated, thistype <strong>of</strong> diarrhoea may last weeks or months, although it may vary in intensity, withexacerbations <strong>and</strong> remissions.In the majority <strong>of</strong> healthy individuals the infection is self-limiting, a proportion(estimated at 30-50%) <strong>of</strong> infected patients, however, will go on to chronic giardiasis,characterised by steatorrhoea accompanied by a classic malabsorption syndromewith substantial weight loss, general debility <strong>and</strong> fatigue. Chronic infectionin early childhood is associated with poor cognitive function <strong>and</strong> failure to thrive.<strong>The</strong> factors determining the variability in <strong>clinical</strong> outcome in giardiasis are poorlyunderstood. Host factors, such as immune status, nutritional status <strong>and</strong> age, as wellas differences in virulence <strong>and</strong> pathogenicity <strong>of</strong> Giardia strains are recognised asimportant factors determining the severity <strong>of</strong> infection. <strong>The</strong> recent application <strong>of</strong>molecular techniques to Giardia lamblia isolates has revealed high levels <strong>of</strong> geneticdiversity within this species. Currently, there are six recognised variants orassemblages (assemblage A, B, C, D, E <strong>and</strong> F), each having a varying degree <strong>of</strong> hostspecificity. Several studies on the correlation between <strong>clinical</strong> presentation <strong>and</strong>genotypes have been performed. However due to the conflicting results reportedin the literature, it is still not completely clear what the relation is between symptoms<strong>and</strong> infection with different genotypes, in particular those belonging toassemblages A <strong>and</strong> B, which are so far the only genotypes known to cause hum<strong>and</strong>isease.Unfortunately in contrast to the case <strong>of</strong> infections with Entamoeba, where it waspossible to define two distinct genotypes that are now named E. histolytica <strong>and</strong> E.dispar, applying such a dichotomy is not (yet) possible with Giardia infections.Worldwide co-operation, including the exchanging <strong>of</strong> the various genotypes <strong>and</strong>st<strong>and</strong>ardisation <strong>of</strong> methods, will eventually reveal some answers to the remainingquestions. By genotyping the different strains it will become possible to study thevariety <strong>of</strong> associated symptoms, although host factors, e.g. host immune responseto infection, will also have to be taken into account.Diagnosis in human infectionsProgress has been made in developing <strong>and</strong> validating non-morphologically baseddiagnostic tests for intestinal parasite antigens. Immun<strong>of</strong>luorescence microscopy(IF), enzyme linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA), parasite DNA polymerasechain reaction - restriction fragment length polymorphism [PCR-RFLP], <strong>and</strong> realtime PCR [RT-PCR]) have all been utilised for Giardia <strong>diagnosis</strong>. However,microscopy is still the cornerstone <strong>and</strong> gold st<strong>and</strong>ard for detecting intestinal parasitesin stool samples in both <strong>clinical</strong> <strong>and</strong> veterinary diagnostic parasitology laboratories.Traditionally fresh or preserved stool samples are microscopically examineddirectly or with (permanent) staining, with or without concentration.Unfortunately, the sensitivity <strong>of</strong> this conventional ovum-<strong>and</strong>-parasite (O&P)examination on a single stool sample for G. lamblia is less than optimal. It wasrecently determined by Cartwright to be only 74% [1]. <strong>The</strong> poor sensitivity <strong>of</strong> asingle parasitological stool examination for diagnosing giardiasis is mainly due tothe variable excretion or low-level shedding <strong>of</strong> the parasite in both symptomatic<strong>and</strong> asymptomatic patients. Furthermore, symptoms can occur before intact parasitesare detected in the stool, hence repeatedexaminations are necessary until morphologicalforms are seen, as is well described <strong>and</strong> recommendedin many parasitology textbooks. To overcomesampling issues, the Triple-Faeces-Test (TFT)was recently developed in the Netherl<strong>and</strong>s as an allround test for the laboratory <strong>diagnosis</strong> <strong>of</strong> intestinalparasites. <strong>The</strong> advantages <strong>of</strong> both fixatives, permanentstaining methods <strong>and</strong> multiple sampling arecombined in this test [2].Figure 4. Cyst stage <strong>of</strong> Giardia,stained with iodine, from a stoolspecimen.Since the early nine-ties enzyme immunosorbentassays (EIAs) for detecting Giardia-specific antigensin stool samples have become commerciallyavailable. A number <strong>of</strong> <strong>clinical</strong> evaluations <strong>of</strong>Giardia EIAs have been reported in the literature;the sensitivity <strong>of</strong> EIA has been found to be eithersimilar, or in most cases slightly superior to single,as well as to multiple, microscopic stool examinations[3-7]. Due to these findings, <strong>and</strong> due to thefact that Giardia lamblia is by far the most commonlyfound enteric pathogen in general practice, EIA is an attractive alternative toconventional O&P examination. However, in the case <strong>of</strong> a negative test result <strong>and</strong>persistent symptoms, a conventional parasitological stool examination, includinga permanent stained smear from a preserved stool sample, should also be performed.Serological approaches to the <strong>diagnosis</strong> <strong>of</strong> giardiasis have been developed <strong>and</strong> havebeen proven to be most useful in epidemiological surveys [8-10]. PCR assays forspecific genera/genotypes <strong>of</strong> intestinal parasites are useful for surveys, but not forthe <strong>clinical</strong> diagnostic laboratory. Stools must be screened for a variety <strong>of</strong>pathogens <strong>and</strong> the cost <strong>of</strong> different PCR assays would be too high. RT-PCR mayhave a role in diagnostic <strong>and</strong> reference laboratories, as several targets could becombined in one multiplex RT-PCR assay, allowing the simultaneous detection <strong>of</strong>multiple infections such as E. histolytica, G. lamblia <strong>and</strong> Cryptosporidium species<strong>and</strong> genotypes infectious to humans.With the use <strong>of</strong> the new approaches in routine parasitological stool examinations,a substantial increase in sensitivity <strong>and</strong> specificity in the laboratory <strong>diagnosis</strong> <strong>of</strong>intestinal protozoan infections can be achieved. Nevertheless it is still extremelyimportantto familiarise physicians with the <strong>clinical</strong> relevance <strong>and</strong> epidemiology <strong>of</strong> theseinfections.Physicians should include a parasitological stool examination in their diagnosticwork-up <strong>of</strong> patients with persistent (lasting longer than 1 week) or intermittentdiarrhoea. This is indicated because <strong>of</strong> the frequency <strong>of</strong> protozoal diarrhoea ingeneral practice, <strong>and</strong> the negligible diagnostic value <strong>of</strong> symptoms <strong>and</strong> otheranamnestic data from patients infected with Giardia lamblia or other intestinalprotozoa, as well as the fact that most intestinal protozoal infections can be treated.EpidemiologyGiardia lamblia is recognised as a major cause <strong>of</strong> diarrheal illness in humans <strong>and</strong>livestock. Worldwide it is one <strong>of</strong> the most important non-viral infectious agentscausing diarrhoeal illness in humans [11-12]. <strong>The</strong> parasite is not restricted topeople living in the developing countries, where sanitation is frequently non-existent<strong>and</strong> people are forced to drink unfiltered surface water, but also occursamong people living in developed, market economies where public hygiene isgood <strong>and</strong> water supplies are purified <strong>and</strong> piped.<strong>The</strong> infection is endemic in all regions <strong>of</strong> the world, <strong>and</strong> also occurs in sporadicepidemic bursts. Exact figures on incidence <strong>and</strong> prevalence depend <strong>of</strong> the populationexamined. In the Netherl<strong>and</strong>s, the prevalence <strong>of</strong> the infection variesbetween 2% <strong>and</strong> 14%, being high in patients who consult their general practitionerwith persistent diarrhoea <strong>and</strong> low (2%) in asymptomatic subjects [13-15].Survival in fresh water has enabled Giardia to achieve the reputation <strong>of</strong> being themost common cause <strong>of</strong> epidemic waterborne diarrheal disease. <strong>The</strong> first record-

P arasitologyAs published in CLI September 2005ed waterborne outbreak <strong>of</strong> giardiasis involved travelers to St. Petersburg, Russia.Since then many epidemics have been well characterised in both North America<strong>and</strong> Europe, <strong>and</strong> they have usually been associated with inadequate water treatment.High rates <strong>of</strong> infection have also been reported for hikers <strong>and</strong> campers inthe USA. Because some <strong>of</strong> these areas were remote from human habitation,infected wild animals, especially beavers, are suspected <strong>of</strong> being a host or reservoirfor Giardia lamblia [16-17].Direct person-to-person spread by faecal-oral transmission is another majormechanism by which the disease is transmitted. <strong>The</strong> organism tends to be foundmore frequently in children or in groups that live in close quarters. Outbreaks <strong>of</strong>giardiasis are well recognised in day care centres, residential institutions <strong>and</strong>schools. Many infections are asymptomatic but spread <strong>of</strong> cysts can occur toother members <strong>of</strong> the family or to other residents. Transmission <strong>of</strong> the parasitealso occurs during sexual activity, in particular as a result <strong>of</strong> intimate oro-analcontact.<strong>The</strong> contribution <strong>of</strong> foodborne transmission <strong>of</strong> giardiasis has not been wellcharacterised. However, there have been a number <strong>of</strong> reports where food hasclearly been identified as the source in several outbreaks <strong>of</strong> giardiasis. In mostcases an infected food h<strong>and</strong>ler has been implicated, presumably transmittingcysts to freshly prepared food [18].TreatmentNitro-imidazoles (metronidazole <strong>and</strong> tinidazole) <strong>and</strong> albendazole are the drugs<strong>of</strong> choice for giardiasis, but lack <strong>of</strong> treatment compliance <strong>and</strong> side effects canresult in treatment failures. For treatment <strong>of</strong> special patient groups e.g., pregnant<strong>and</strong> immunocompromised patients, alternative drugs, such as paromomycin,<strong>and</strong>/or prolonged or combination therapy may sometimes be necessary.References1. Cartwright CP. Utility <strong>of</strong> multiple-stool-specimen ova <strong>and</strong> parasite examinations in ahigh-prevalence setting. Journal <strong>of</strong> Clinical Microbiology 1999; 37: 2408-2411.2. Gool T, Mank TG. Triple faeces test: an effective tool for detection <strong>of</strong> intestinal parasitesin routine <strong>clinical</strong> practice Eur J Clin Microbio Infec Dis 2003; 22: 284-290.3. Mank TG et al. Sensitivity <strong>of</strong> microscopy versus enzyme immunoassay in the laboratory<strong>diagnosis</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Giardiasis</strong>. European Journal <strong>of</strong> Clinical Microbiology 1997; 16: 615-619.4. Garcia LS, Shimizu RY. Evaluation <strong>of</strong> nine immunoassay kits (enzyme immunoassay<strong>and</strong> direct fluorescence) for detection <strong>of</strong> Giardia lamblia <strong>and</strong> Cryptosporidium parvumin human fecal specimens. Journal <strong>of</strong> Clinical Microbiology 1997; 35: 1526-1529.5. Ros<strong>of</strong>f JD et al. Stool <strong>diagnosis</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Giardiasis</strong> using a commercially available enzymeimmunoassay to detect Giardia-specific antigen 65. Journal <strong>of</strong> Clinical Microbiology 1989; 27:1997-2002.6. Scheffer EA,Van Etta LL. Evaluation <strong>of</strong> a rapid commercial enzyme immunoassay for detection<strong>of</strong> Giardia lamblia in formalin-preserved stool specimens. Journal <strong>of</strong> ClinicalMicrobiology 1994; 32: 1807-1808.7. Zimmerman SK, Needham CA. Comparison <strong>of</strong> conventional stool concentration <strong>and</strong> preserved-smearmethods with Merifluor Cryptosporidium/Giardia direct immun<strong>of</strong>luorescenceassay <strong>and</strong> ProSpect Giardia EZ microplate assay for detection <strong>of</strong> Giardia lamblia. Journal <strong>of</strong>Clinical Microbiology 1995;33: 1942-1943.8. Isaac-Renton JL et al.Epidemic <strong>and</strong> endemic seroprevalence<strong>of</strong> antibodies toCryptosporidium <strong>and</strong> Giardiain residents <strong>of</strong> three communitieswith different drinkingwater supplies. Am J TropMed Hyg 1999; 60: 578-583.9. Isaac-Renton JL et al.A secondcommunity outbreak <strong>of</strong>waterborne giardiasis inCanada <strong>and</strong> serological investigation<strong>of</strong> patients. Trans RSoc Trop Med Hyg 1994; 88:395-399.10. Miotti PG et al. Age-relatedrate <strong>of</strong> seropositivity <strong>of</strong>antibody to Giardia lamblia in four diverse populations. J Clin Microbiol 1986; 24: 972-975.11. Meyer EA. 1990 Taxonomy <strong>and</strong> nomenclature. In: EA Meyer (ed.), <strong>Giardiasis</strong>.,Amsterdam:Elsevier Holl<strong>and</strong>, 1999, p 51-60.12. Thompson RCA et al. Giardia- from molecules to disease <strong>and</strong> beyond. Parasitology today1993; 9: 313-315.13. Mank TG et al. Comparison <strong>of</strong> fresh versus sodium acetate acetic acid formalin preservedstool specimens for <strong>diagnosis</strong> <strong>of</strong> intestinal protozoal infections. European Journal <strong>of</strong> ClinicalMicrobiology <strong>and</strong> Infectious Diseases 1995; 14: 1076-1081.14. Mank TG et al. Persistent diarrhoea in a general practice population in the Netherl<strong>and</strong>s,prevalence <strong>of</strong> protozoal <strong>and</strong> other intestinal infections. In: Proceedings <strong>of</strong> the IXthInternational Congress <strong>of</strong> Parasitology, Chiba, Japan,pp. 803-807.15. Wit Mas DE et al. Gastroenteritis in sentinel general practices, the Netherl<strong>and</strong>s. EmergingInfectious Diseases 2001; 7: 82-91.16. Dykes AC et al. Municipal waterborne giardiasis. An epidemiologic investigation. AnnIntern Med 1980; 93: 165-170.17. Healy GR. <strong>Giardiasis</strong> in perspective: the evidence <strong>of</strong> animals as a source <strong>of</strong> human Giardiainfections, p 305-313. In: EA Meyer (ed.), <strong>Giardiasis</strong>. Human Parasitic Diseases, vol. 3. NewYork: Elsevier Biomedical Press, 1990.18. Adam RD. <strong>The</strong> biology <strong>of</strong> Giardia spp. Microbiological Reviews 1991; 55: 706-732.<strong>The</strong> author<strong>The</strong>o G Mank, Ph.D.Medical ParasitologistDepartment <strong>of</strong> ParasitologyPublic Health Laboratory HaarlemBoerhaavelaan 262035 RC Haarlem<strong>The</strong> Netherl<strong>and</strong>sTel.: +31 23 5307800Fax: +31 23 5307805E-mail: t.mank@streeklabhaarlem.nlFigure 5. Circular lesions on the mucosa <strong>of</strong> a mouse smallintestine resulting from attachment <strong>of</strong> Giardia muris.