Wynehamer v People.pdf - The University of Texas at Austin

Wynehamer v People.pdf - The University of Texas at Austin

Wynehamer v People.pdf - The University of Texas at Austin

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

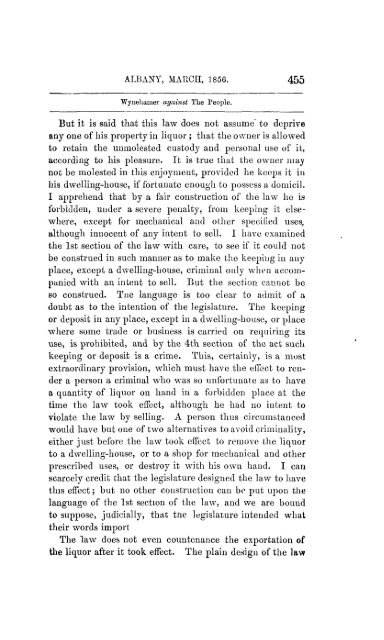

ALBANY, MARCH, 1856. 455<strong>Wynehamer</strong> against <strong>The</strong> <strong>People</strong>.But it is said th<strong>at</strong> this law does not assume' to depriveany one <strong>of</strong> his property in liquor ; th<strong>at</strong> the owner is allowedto retain the unmolested custody and personal use <strong>of</strong> it,according to his pleasure. It is true th<strong>at</strong> the owner maynot be molested in this enjoyment, provided he keeps it inhis dwelling-house, if fortun<strong>at</strong>e enough to possess a domicil.I apprehend th<strong>at</strong> by a fair construction <strong>of</strong> the law he isforbidden, under a severe penalty, from keeping it elsewhere,except for mechanical and other specified uses,although innocent <strong>of</strong> any intent to sell. I have examinedthe 1st section <strong>of</strong> the law with care, to see if it could notbe construed in such manner as to make the keeping in anyplace, except a dwelling-house, criminal only when accompaniedwith an intent to sell. But the section cannot beso construed. Tne language is too clear to admit <strong>of</strong> adoubt as to the intention <strong>of</strong> the legisl<strong>at</strong>ure. <strong>The</strong> keepingor deposit in anyplace, except in a dwelling-house, or placewhere some trade or business is carried on requiring itsuse, is prohibited, and by the 4th section <strong>of</strong> the act suchkeeping or deposit is a crime. This, certainly, is a mostextraordinary provision, which must have the effect to rendera person a criminal who was so unfortun<strong>at</strong>e as to havea quantity <strong>of</strong> liquor on hand in a forbidden place <strong>at</strong> thetime the law took effect, although he had no intent toviol<strong>at</strong>e the law by selling. A person thus circumstancedwould have but one <strong>of</strong> two altern<strong>at</strong>ives to avoid criminality,either just before the law took effect to remove the liquorto a dwelling-house, or to a shop for mechanical and otherprescribed uses, or destroy it with his own hand. I canscarcely credit th<strong>at</strong> the legisl<strong>at</strong>ure designed the law to havethis effect; but no other construction can be put upon thelanguage <strong>of</strong> the 1st section <strong>of</strong> the law, and we are boundto suppose, judicially, th<strong>at</strong> tne legisl<strong>at</strong>ure intended wh<strong>at</strong>their words import<strong>The</strong> law does not even countenance the export<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong>the liquor after it took effect. <strong>The</strong> plain design <strong>of</strong> the law