Perner 2010.pdf

Perner 2010.pdf

Perner 2010.pdf

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Page 24115 Who took the cog out ofcognitive science? 1Mentalism in an era ofanti-cognitivismNOT FOR DISTRIBUTIONJosef <strong>Perner</strong>Brief naïve reflections on our behaviorist and cognitivist pastBehaviorism I remember as the doctrine of the black box: stick to theobservable input and output of a system, and refrain from theorizing aboutthe system’s internal clockwork of cog wheels (“cog-works” for short) thatcreate the causal connections between observable stimuli and responses. TheCognitive Revolution supposedly opened the black box to theory.Behaviorism had another doctrine: the empty slate to be filled by learning.This gave it predictive power, which critically depended on how the observablelearning history changes the observable input–output function. A growingrealization that the genetic determination of our knowledge cannot beignored helped the downfall of behaviorism, which only had place for knowledgeacquisition through learning. This breach with behaviorism was heraldedas the “cognitive revolution”, boosted by the first-time availability ofmore powerful computers with the promise of “intelligence” that had specifiablecognitions (program).The rise of nativism filled a lacuna in behaviorism’s account of knowledgeacquisition. However, it did little to enlighten the black box. Indeed, especiallywhen paired with modularity of processing, the negative argumentsagainst learnability of concepts and knowledge did little more than break upthe one big box into smaller boxes of domain-specific knowledge. But theblackness of these smaller boxes, if anything, deepened because their internalstructure couldn’t even be explored by learning. Also the equilibratingprocesses and resulting group structures of Piaget’s (1971, 1972) genetic epistemologydid not provide a lasting replacement of learning theory. In consequence,cognitive development and also the comparative study of cognitionbecame a question of documenting which body of knowledge can be demonstratedin which species or at which age in humans without analysis of thecog-nitive underpinnings of this knowledge.This anti-cognitivism was reinforced by the nativist reaction to classicalbehaviorism – not because nativism is inherently anti-cognitive but becausethe present genetic knowledge does not (yet) provide a cognitively explicitanalysis of how knowledge is encoded and epigenetically unfolds. ModularismPerception, attention, and action:International Perspectives on Psychological Science (Volume1). Peter A. Frensch and Ralf Schwarzer (Eds). 2010.Published by Psychology Press on behalf of the International Union of Psychological Science.This proof is for the use of the author only. Any substantial or systematic reproduction,re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in anyform to anyone is expressly forbidden.15:58:17:03:10Page 241

Page 242242 <strong>Perner</strong>gave this tendency its stamp of approval. Again, there is no intrinsic reason torefrain from cognitive analysis of the innards of modules, but the focus is onthe module doing its job regardless of its complicated internal workings.Moreover, modularity provided a useful launch pad for neurocognition andfunctional brain imaging as it provided theoretical reasons for there to belocalizable brain regions responsible for particular knowledge domains. Alsothe clinical drive for developing tests of differential potential in specific knowledgedomains did not help cognitive explicitness. Like intelligence tests, suchtests help differentiate people’s level of ability but do not illuminate the cognitiveunderpinnings of intellectual functioning. In sum, all this had theironic consequence that the heirs of the cognitive revolution became in someof their extreme forms more anti-cognitivist than behaviorism ever was (atleast the structure of the learned material shed some light on the cognitivestructure).My concern here is the particular knowledge domain of folk psychology ortheory of mind. It, too, is increasingly and exclusively treated as anunanalysed ability. My plea in this chapter is to return to a more explicitcognitive analysis to help shed light on the intransigent dispute betweenboosters’ mentalist interpretations (Tomasello & Call, 2006) and scoffers’ 2“behavior-rule” (Povinelli & Vonk, 2004) interpretations of nonhuman animals’social competence. And similarly, help is required for explaining humaninfants’ precocious “implicit” understanding of the mind (false beliefs;Onishi & Baillargeon, 2005) in view of their known problems until later inchildhood on direct, “explicit” tests of false belief (Clements & <strong>Perner</strong>, 1994).NOT FOR DISTRIBUTIONPovinelli’s challenge: Mentalism or “behavior rules”Do chimpanzees, who are excellent gaze-followers and have intricate understandingof where someone else is looking, also understand that lookingleads to knowledge, which then influences the knower’s behavior? After manynegative results under strict experimental control (Povinelli & Eddy, 1996)using cooperative set-ups, more positive evidence emerged finally from foodcompetitionsituations (Hare, Call, Agnetta, & Tomasello, 2000; Hare &Tomasello, 2001). Subordinate individuals observe carefully the dominant’slooking behavior when food is being placed. Registration of the dominant’svisual access influences the likelihood of the subordinate’s dashing for thebait, expressing appreciation of the fact that the dominant is less likely toclaim the bait if he has not been able to see it being placed than when he didsee the baiting. Povinelli and Vonk (2003, 2004) claimed that the subordinate’sfeat does not establish understanding of the dominant’s mind (knowledgestate) mediating between his looking and going for the bait. Rather, itcan be understood on the basis of “behavior rules” that capture the regularityof how the dominant’s visual access influences his likely behavior, withouthaving to understand that there is a mental state of knowledge mediatingbetween visual access and behavior.Perception, attention, and action:International Perspectives on Psychological Science (Volume1). Peter A. Frensch and Ralf Schwarzer (Eds). 2010.Published by Psychology Press on behalf of the International Union of Psychological Science.This proof is for the use of the author only. Any substantial or systematic reproduction,re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in anyform to anyone is expressly forbidden.15:58:17:03:10Page 242

Page 243Anti-cognitivism infiltrates theory of mind 243This controversy is marked by much discussion of what possible behaviorrules there could be to account for the range of available data. One argument(Tomasello & Call, 2006) was that the scoffers, who denigrate the animal’sabilities, have to assume so many more different explanations than theboosters, who grant the animal mental insight: “the boosters clearly haveparsimony on their side. The number of different explanations requiredto explain the evidence is sensibly smaller (12 versus 1 for 12 items of evidence)”(p. 380). This conclusion is a good demonstration of the current anticognitivismof the mentalist boosters. They treat mentalism as a singleexplanation, in contrast to the myriad of behavior rule explanations requiredto cover the evidence. This is to overlook that a cognitive analysis of theanimals’ mentalism also requires a myriad of rules – in fact, for this particularcase, as many plus one as there are behavior rules required.Without going into details of the nature of the required behavior rules, Ifocus on the general observation by Povinelli and Vonk (2004):NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION. . . the subject’s predictions about the other agent’s future behaviorcould be made either on the basis of a single step from knowledge aboutthe contingent relationships between the relevant invariant features ofthe agent and the agent’s subsequent behavior, or on the basis of multiplesteps from the invariant features, to the mental state, to the predictedbehavior. (pp. 8–9)This general observation then issues into my Recipe for posing Povinelli’schallenge:Let the Mentalist give you a specification of the inference proceduresrequired to get from what the animal observes to the ensuing mental stateand from that state to the predicted behavior. Collapse these inference rulesinto one that allows inference of the predicted behavior directly from whatthe animal observes.So, in case of food competition, a Mentalist has to specify for the subordinatechimp something like the following two computational inference procedures(CIPs), where “S” stands for the observable situation including the dominant’slooking behavior, “m” for an unobservable, to-be-inferred mental state(knows about food), “A” for the to-be-predicted action (e.g., goes for bait),and “→” for the respective CIPs on which these (subconscious) inferences arebased:S → m:“IF a dominant D looks at (has visual access to) a bait Bbeing placed at location L,THEN P knows 3 that B is at L.”Perception, attention, and action:International Perspectives on Psychological Science (Volume1). Peter A. Frensch and Ralf Schwarzer (Eds). 2010.Published by Psychology Press on behalf of the International Union of Psychological Science.This proof is for the use of the author only. Any substantial or systematic reproduction,re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in anyform to anyone is expressly forbidden.15:58:17:03:10Page 243

Page 244244 <strong>Perner</strong>m → A:“IF a dominant D knows that B is at LTHEN D will go to get B at L as soon as he is able to (isreleased from the cage).”For this case, Povinelli’s Challenge can be easily posed with the followingsituation–action inference procedure (i.e., “behavior rule”): 4NOT FOR DISTRIBUTIONS → A:“IF a dominant D looks at (has visual access to) a bait Bbeing placed at location L,THEN D will go to get B at L as soon as he is able to (isreleased from the cage).”This similarity in CIPs creates a problem about what evidence could possiblydecide between “behavior rules” and “mental rules”. Notably, severalsuggestions by Call and Tomasello (2008) won’t do the trick.(1) Timing: The fact that the subordinate’s decision is influenced by thedominant having looked at the baiting earlier, and does not look there at thetime of the subordinate’s decision, does not make any difference. The S→Arule can just be expressed in terms of “looked at the baiting”.(2) Intentional content: “This means that they knew not just where theother was looking, but they knew the content of what the others saw – thefood – because only with this knowledge could they predict her action”(Tomasello & Call, 2006, p. 376). Looking at a particular location L in spaceand looking at an object at that location are both observable states of theenvironment. So there is no need to infer an unobservable mental state ofseeing food in a location apart from the looking at food in that location. Thereis no need to introduce a distinction between the target of what the other islooking at (the food in location L) and a separate intentional content of howthe food in location L is seen by the other.(3) Flexibility: A central point in Table 17.1 of Tomasello and Call is thefact that not only can subordinates predict the dominant’s likely behavior inspecific conditions but they are very flexible – for example, they go for thefood behind an opaque barrier if the dominant did not see it put there butrefrain from going when he did witness the hiding. Moreover, they did not gofor the bait even when the dominant did not witness the baiting but the baitwas behind a transparent barrier, etc. What a cognitive analysis of mentalstate attribution makes clear is that these cases need great sophistication inknowing when the dominant will or won’t know about the food. Each caseasks for a different CIP:D looks at baiting of the opaque box → D knows about bait → he willclaim it.Perception, attention, and action:International Perspectives on Psychological Science (Volume1). Peter A. Frensch and Ralf Schwarzer (Eds). 2010.Published by Psychology Press on behalf of the International Union of Psychological Science.This proof is for the use of the author only. Any substantial or systematic reproduction,re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in anyform to anyone is expressly forbidden.15:58:17:03:10Page 244

Page 245Anti-cognitivism infiltrates theory of mind 245D doesn’t look at baiting of opaque box → D doesn’t know about bait→ he will not claim it.D looks at transparent box → D knows about bait → he will claim it....etc....NOT FOR DISTRIBUTIONPovinelli and Vonk’s (2004) point generalizes to the insight that behaviorrules do not complicate the matter in any way but actually simplify it becauseone gets the same predictive power by simply dropping the middle part with“know” in the inferential chain. Tomasello and Call’s intuition holds only ifone treats mentalism as a cognitively opaque but (for us) easy to apply abilityand contrasts it with a cognitively more explicit (and for us cumbersome)behavior rule specification – that is, conflating the complexity of the systemwith what is easy for us (see Heyes, 1998, p. 110). 5(4) Understanding goals: Call and Tomasello (2008) summarize evidencefor chimpanzees and human infants appreciating that actors pursue goalsand have intentions. Again there needs to be some observable behavior inthe given situation that allows a computational procedure to infer whatthe actor’s goal or intentions might be. For instance, chimps beg moreintensely from a keeper if he is unwilling than when he is unable to delivera grape. This is marked as particularly relevant, because the behavior ofthe keeper is very similar in these two cases. Clearly the chimps havethe ability (innate or learned) to make this fine behavioral distinction andare sensitive to the relevant consequences, which, presumably, are that thereis less point in keeping pestering an unwilling than a willing but clumsykeeper. It falls upon the mentalist to explain why exactly the chimpsreact that way. The challenger then simply needs to drop the mental parts inthat explanation. In this case we might get the following competingexplanations:(1) reluctant behavior → keeper does not want to surrender grape → nopoint persisting,(2) reluctant behavior → no point persisting.The question remains as to what in the evidence helps us decide between thesetwo alternatives.In sum, the prolonged dispute has shown how difficult it is to design a testfor deciding between use of a theory of mind and direct behavioral inferences(“behavior rules”). But it is not impossible to find such a test. The secret, asWhiten (1996) has made amply clear, lies in the essence of intentional action –namely, the interaction between instrumental conditions (the given facts;belief-inducing situation) and what is to be achieved (the goal or purpose;desire-inducing situation) that provide the reasons for action.Perception, attention, and action:International Perspectives on Psychological Science (Volume1). Peter A. Frensch and Ralf Schwarzer (Eds). 2010.Published by Psychology Press on behalf of the International Union of Psychological Science.This proof is for the use of the author only. Any substantial or systematic reproduction,re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in anyform to anyone is expressly forbidden.15:58:17:03:10Page 245

Page 246246 <strong>Perner</strong>Going beyond Povinelli’s ChallengeThe problem so far with trying to decide between theories is that for eachtheory-of-mind rule (“S→m→A” CIPs) for a particular action A, a behaviorrule (“S→A” CIP) can be found. That is, both theories explain the sameinput–output function, and no empirical test is possible on these grounds.Moreover, whether we assume that these CIPs are learned or innate, in neithercase are there convincing arguments that behavior rules are more or lesslikely to exist than theory-of-mind rules.Although the input–output functions are the same, the internal structuresof the theories differ. This difference becomes apparent when we look at theinteraction between beliefs and desires (conditions and goals). I illustratethis structural difference with help of the false-belief test used on children(Wimmer & <strong>Perner</strong>, 1983):NOT FOR DISTRIBUTIONA protagonist P puts an object O in location L1. O is unexpectedly transferredin P’s absence to location L2. Children have to predict whether P willgo to L1 or L2 to get O.To give a reasoned answer, something like the following CIPs are required:Mentalist CIPs:S → m:m → A:“IF a person P looks at an object O being put inside a locationL1, and does not look when it is transferred to locationL2, THEN P believes that O is still in L1.”“IF a person P wants to get an object O, and P believes that Ois in location L,THEN P will go to L.”Behavior Rule (SA-CIP): 6S → A:“IF a person P looks at an object O being put inside a locationL1, and does not look when it is transferred to locationL2, AND IF P is 7 to get the object O,THEN P will go to L1.”This example makes clear that there are two elements on the input side.One specifies where the object is seen by the person which gives rise to wherethe person thinks it is (belief-inducing), and the other specifies what the personis supposed to do (response demands, purpose) which gives rise to whatthe person allegedly wants to do (desire-inducing) – namely, to get the object.Perception, attention, and action:International Perspectives on Psychological Science (Volume1). Peter A. Frensch and Ralf Schwarzer (Eds). 2010.Published by Psychology Press on behalf of the International Union of Psychological Science.This proof is for the use of the author only. Any substantial or systematic reproduction,re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in anyform to anyone is expressly forbidden.15:58:17:03:10Page 246

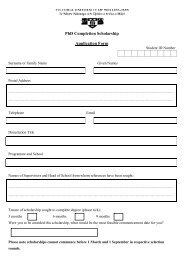

Page 247Anti-cognitivism infiltrates theory of mind 247The input elements giving rise to the respective mental states can varybut result in the same belief and desire. For instance, if we change the story:instead of failing to witness the unexpected transfer of the object from L1 toL2 the person simply is being misinformed that the object (in L2) is in L1;from this we can infer that the person believes the object to be in locationL1. So these are two different ways of getting the person to believe that O is inL1. We can also add a new desire-inducing response demand or purpose.Instead of P to get the object, P may be asked to say where the object is.Combination of the two different belief-inducing and two desire-inducingelements results in the following four situations, which are also illustrated inFigure 15.1:NOT FOR DISTRIBUTIONS1: Unexpected transfer from L1 to L2 A1: P will go to L1& P is going to get OS2: Unexpected transfer from L1 to L2 A2: P will say “O is in L1.”& P asked where O isS3: P told that O in L1 & P is going to A3: P will go to L1get OS4: P told that O in L1 & P asked A4: P will say “O is in L1.”where O isTo make correct action predictions in all four cases, a mentalist has to positthe following set of rules (CIPs):Epistemic (S→b) inference procedures:Sb-CIP1: Unexpected transfer from L1 to L2 → 8 P believes O is in L1Sb-CIP2: P told that O in L1 → P believes O is in L1Connative (S→d) inference procedures:Sd-CIP1: P is going to get O → P wants to get OSd-CIP2: P asked where O is → P wants to tell where O isAction (bd→A) inference procedures:bdA-CIP1: P thinks O is in L1 &P wants to get object O → 9 P will go to L1bdA-CIP2: P thinks O is in L1 &P wants to tell where O is → P will say “O is in L1”Perception, attention, and action:International Perspectives on Psychological Science (Volume1). Peter A. Frensch and Ralf Schwarzer (Eds). 2010.Published by Psychology Press on behalf of the International Union of Psychological Science.This proof is for the use of the author only. Any substantial or systematic reproduction,re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in anyform to anyone is expressly forbidden.15:58:17:03:10Page 247

Page 248248 <strong>Perner</strong>NOT FOR DISTRIBUTIONFigure 15.1 Illustration of two different belief-inducing situations in combinationwith two different desire-inducing response demands.For the behavior rule approach, these can be reduced to four rules:Behavior rules (S→A CIPs):SA-CIP1: Unexpected transfer from L1 toL2 & P is going to get O → 10 P will go to L1sSA-CIP2: Unexpected transfer from L1 toL2 & P asked where O is → P will say “O is in L1”Perception, attention, and action:International Perspectives on Psychological Science (Volume1). Peter A. Frensch and Ralf Schwarzer (Eds). 2010.Published by Psychology Press on behalf of the International Union of Psychological Science.This proof is for the use of the author only. Any substantial or systematic reproduction,re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in anyform to anyone is expressly forbidden.15:58:17:03:10Page 248

Page 249SA-CIP3:SA-CIP4:Anti-cognitivism infiltrates theory of mind 249P told that O in L1 & P isgoing to get O→ P will go to L1P told that O in L1 & Pasked where O is → P will say “O is in L1”But these behavior rules are differently structured from the mentalist inferences.This gives us empirically testable predictions. For instance, imagine achild who reliably makes correct predictions for three of the four situationsbut fails to understand in S3 that a person who is told that O is in L1 andwants to get O, will go to L1. If the child uses behavior rules, this pattern ofresults is easily explained by the fact that this child simply lacks SA-CIP3. Ifthe child uses mentalist inference rules, this pattern becomes a mystery: Masteryof the other three situations shows that the child possesses both therelevant Sb- and Sd-CIPs, can combine beliefs with desires, and possesses therelevant bdA-CIP, which are all the ingredients for a making a correct predictionin S3. So why does the child fail on S3? Presumably, the child does notuse a theory of mind to make the predictions for the other situations. Thisexample shows that the answer pattern over combinations of different beliefinducingcircumstances and different desire-inducing response demandsmakes the mentalist approach falsifiable (as every empirically informativetheory needs to be). It is more difficult to extract a falsification for behaviorrules. Additional assumptions are need.Let us assume that we have control over the acquisition process for CIPs.Then we can work with transfer tests. If CIPs can be taught, then we couldtrain our subjects on S1 and S4, say. If their acquired competence is based onbehavior rules SA-CIP1 and SA-CIP4, then no transfer to situations S2 andS3 are to be expected, since the corresponding CIPs have not been learned. Incontrast, if the competence is based on mentalist CIPs, then the training onsituation S1 must have installed Sb-CIP1 and Sd-CIP1 and bdA-CIP1, similarlyfor training on S4: Sb-CIP2 and Sd-CIP2 and bdA-CIP2. This providesall the component CIPs necessary for situations S2 (put in bold type) and forS3 (underlined). Consequently, after training on S1 and S4, competenceshould easily transfer to untrained situations S2 and S3 on mentalist assumptions.If such transfer occurs, we have evidence against the use of behaviorrules, and failure of transfer speaks against the use of mentalism.So far so good – provided we can gain control over acquisition. If the claimis that children or animals are innately endowed with such knowledge, thenthe transfer test becomes impotent. The reason is simple. We do not knowenough about the genetic and epigenetic basis of innate knowledge to interveneat the level of individual input–output links to give behavioral tests thepower to distinguish between different CIP-structures (mentalist orbehavioral rules). Moreover, once genetic analysis does allow us such intervention,then behavioral tests will have become obsolete, since our geneticcontrol is more likely to aim at individual CIPs directly than at their inputNOT FOR DISTRIBUTIONPerception, attention, and action:International Perspectives on Psychological Science (Volume1). Peter A. Frensch and Ralf Schwarzer (Eds). 2010.Published by Psychology Press on behalf of the International Union of Psychological Science.This proof is for the use of the author only. Any substantial or systematic reproduction,re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in anyform to anyone is expressly forbidden.15:58:17:03:10Page 249

Page 250250 <strong>Perner</strong>and output relationship. Strong belief in the future benefits of nativismmakes cognitive analysis with available means seem pointless.Mentalism: What develops?The worry about how to distinguish use of behavior rules from use of amentalistic theory has plagued comparative psychology more than developmentalpsychology. The reason for this is twofold. For one, we are convincedthat we as adults use a theory of mind to explain behavior, hence signs ofchildren’s understanding are uncritically accepted as such. Also, untilrecently the developmental trajectory of this emerging understanding seemedstraight forward. For instance, children’s understanding of the critical conceptof belief seemed to appear around 4 years, when they stop makingwrong predictions in the false-belief paradigm. This picture has recentlybecome more complicated by the finding that although children younger than4 years find it hard to give the correct answer to the question of where amistaken protagonist will look for an object (direct test assessing “explicit”understanding), much younger children show signs of understanding onother measures – for example, looking in expectation (indirect tests assessing“implicit” understanding).These findings lead me to rethink our sanguine trust in passing the falsebelieftest being a sure sign of a theory of mind. Three questions arise pertainingto Povinelli’s Challenge:NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION1 Does the original, direct false-belief test show use of mentalist rules oronly of behavior rules? 112 Does precocious performance on indirect tests show use of mentalist orbehavior rules?3 Might the use of behavior rules count as an implicit understanding ofthe mind?Does the traditional false-belief test meet Povinelli’s Challenge?There is no obvious reason why children’s correct behavioral predictions onthe test could not be based on a use of behavior rules. We have to look at thepattern over different false-belief-inducing situations combined with differentresponse demands. Few studies systematically compared different conditions.By and large, findings show little difference in the age at which childrenmaster the different versions. <strong>Perner</strong> and Wimmer (1988) compared theunexpected transfer paradigm with the misinformation paradigm on 80German- and 80 English-speaking children and found no difference betweenparadigms. The most widely used variations are the unexpected transfer test(Wimmer & <strong>Perner</strong>, 1983) and the unexpected content (Smarties box containingpencils; Hogrefe, Wimmer, & <strong>Perner</strong>, 1986; <strong>Perner</strong>, Leekam, & Wimmer,1987). These tests differ in terms of how the belief is induced, and childrenPerception, attention, and action:International Perspectives on Psychological Science (Volume1). Peter A. Frensch and Ralf Schwarzer (Eds). 2010.Published by Psychology Press on behalf of the International Union of Psychological Science.This proof is for the use of the author only. Any substantial or systematic reproduction,re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in anyform to anyone is expressly forbidden.15:58:17:03:10Page 250

Page 251Anti-cognitivism infiltrates theory of mind 251have to predict different actions (where protagonist will go or what he willanswer) or describe directly what the protagonist thinks (a method notapplicable to nonverbal investigations). All these factors do not lead to anysignificant differences in a large meta-analysis (Wellman, Cross, & Watson,2001). Call and Tomasello (1999) used a particularly interesting versioninvolving identically looking containers and turned it into a nonverbal test:children, who did not know in which container the object was had to inferfrom a misled person’s well-intended but wrong cue where the object reallywas. Despite these changes in procedure and the test’s intuitive complexity,children solved the task at the same age as the traditional false-belief test. 12In sum, although no systematic attempt was made to compare the onsetage for solving different false-belief tests that vary in belief- and desireinducingconditions, the data from different experiments suggest that no greatvariation occurs. This poses a problem for a theory of behavior rules beinglearned. For, if they were learned, then frequently occurring situations, as inthe unexpected change task, should be mastered much earlier than rarelyoccurring combinations – for example, that a person who instructs someoneto move an object, but that person forgets to do so, will look in the object’ssupposed new location (<strong>Perner</strong> et al., 1987, Expt. 1; replication: Doherty &<strong>Perner</strong>, 1998, Expt. 4). But there is no striking difference in children’s mastery.In that weak sense, of speaking against the learning of behavior rules,the false-belief test does meet Povinelli’s Challenge. However, any claim thata set of genetically predisposed behavior rules matures at this age cannot beruled out. The data also pose interesting constraints for the acquisition of atheory of mind. They make it unlikely that the individual CIPs are learned.The reasons are the same as for learning behavior rules.The false-belief test also provides qualitatively distinct evidence in the formof children using mental terminology in explaining the protagonist’s erroneousaction. Unequivocal evidence of this kind emerges, however, with somedelay after making correct behavioral predictions (<strong>Perner</strong>, Lang, & Kloo,2002; Wimmer & Mayringer, 1998). For instance, of 20 4-year-olds (3½ to 4½years), 10 gave correct predictions but only 6 gave sensible explanations(Wimmer & Mayringer, 1998, Expt. 1). The number of children giving correctexplanations increased to 14 at age 5 years, and to 16 at 6 years – altogether60% of all 60 children. However only 14 of the 36 correct explanations referencedmental states (8 said “because he thinks the ice-cream man stays there”,and 6, “because the ice-cream man was there and he didn’t know that he isnow at the station”). The remaining “sensible” explanations made referenceto the original location (e.g., “because Ann had put the book in there”, “thebook was in there”, or, “because he saw the ice cream man there”) which mayimply reference to mental states but is also compatible with justifications interms of behavior rules: people go to get objects where they had put them, orlast seen them (looked at them when being placed). So, on the basis of explicitverbal justifications, the false-belief test meets Povinelli’s Challenge only forsome 5- to 6-year-old children.NOT FOR DISTRIBUTIONPerception, attention, and action:International Perspectives on Psychological Science (Volume1). Peter A. Frensch and Ralf Schwarzer (Eds). 2010.Published by Psychology Press on behalf of the International Union of Psychological Science.This proof is for the use of the author only. Any substantial or systematic reproduction,re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in anyform to anyone is expressly forbidden.15:58:17:03:10Page 251

Page 252252 <strong>Perner</strong>Do precocious signs of understanding belief meetPovinelli’s Challenge?The meta-analysis by Wellman et al. (2001) showed that despite manyattempts to demonstrate understanding false belief before the age of 4 years,no factor emerged that could reliably achieve this. Single studies reportinglarger proportions of successful younger children appeared to be ephemeralblips. Only the results from using indirect measures of understanding(Clements & <strong>Perner</strong>, 1994) have been replicated on a larger scale after publicationof the meta-analysis. Signs of appreciating false belief appear reliably ina majority of children at or just before the age of 3 years. In the basic set-up,the story protagonist disappears and returns via one of two doors. Thisallows checking on children’s expectations of where the protagonist willreturn by recording their eye gaze. And, indeed, a majority of 3-year-oldslook at the door next to the location where the protagonist thinks his objectis, while almost all of them predict, when asked, that he will reappear at theother door near where the object actually is. This admittedly curious findinghas been securely replicated (e.g., Garnham & <strong>Perner</strong>, 2001; Garnham &Ruffman, 2001; Low, 2007; Ruffman, Garnham, Import, & Connolly, 2001).Moreover, when the object in question disappears from the scene, a similarfinding has been reported in children as young as 2 years (Southgate, Senju, &Csibra, 2007), 13 or even younger (Southgate 2008).Another group of studies claimed even earlier sensitivity to false beliefusing looking time as the dependent measure. The duration of looking at anerroneous action is compared to looking at a successful action. Longer lookingat the successful action than at the erroneous action in cases of false beliefis interpreted as children being surprised about a successful action when theactor has a false belief. These data indicate sensitivity to the protagonist’sbelief as early as 14 or 15 months (Onishi & Baillargeon 2005; Surian, Caldi,& Sperber, 2007). One problem with these data is that the looking-time differencesare multiply interpretable and not a clear indicator of expectation(<strong>Perner</strong> & Ruffman 2005; Sirois & Jackson, 2007). Here I just want to pointout that the looking-time differences 14 and the looking in expectation can beexplained by the use of behavior rules (SA-CIPs).Two features help defend this explanation. (1) The measures employed areall indirect tests 15 as opposed to the direct tests of belief-based behavior in thetraditional false-belief tests. This can explain why 3-year-old children look atthe point of reappearance where the protagonist thinks the object is whereas,when asked, they steadfastly claim that he will reappear from the door nearwhere the object actually is. This is in analogy to implicit memory. Havingseen a word on a list can make it demonstrably more likely to find it as asolution to an anagram (indirect test) even when there is complete failure ofidentifying the word as a member of the list on a (direct) recognition test. (2)These original demonstrations of precocious sensitivity use a quite narrowrange of both belief-inducing situations and response demands – that is,NOT FOR DISTRIBUTIONPerception, attention, and action:International Perspectives on Psychological Science (Volume1). Peter A. Frensch and Ralf Schwarzer (Eds). 2010.Published by Psychology Press on behalf of the International Union of Psychological Science.This proof is for the use of the author only. Any substantial or systematic reproduction,re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in anyform to anyone is expressly forbidden.15:58:17:03:10Page 252

Page 253Anti-cognitivism infiltrates theory of mind 253unexpected change and retrieval of an object. So it is unlikely that the existingdata provide evidence of simultaneity of mastering different situation–purpose combinations required to rule out learning of behavior rules. 16 However,researchers are now working intensively on a variety of belief-inducingsituations.Symposium S-104 at ICP 2008 contained several ingenious contributions. Ican pick but one for detailed analysis: Scott and Baillargeon (2008) showedinfants two identically looking dotted cups and a striped cup and demonstratedthat one dotted cup and the striped cup rattle when shaken, while theother dotted cup remains silent. In the false-belief condition infants then sawhow the rattling of one of the dotted cups was demonstrated to a new person,who was then encouraged to do the same with one of the two other cups.Infants looked longer when that person shook the striped cup than the otherdotted cup. When, in a knowledge condition, that person was present whilethe properties of the cups were demonstrated to the infants themselves, theirlooking pattern reversed. How might the mentalist analyse the underlyingcognitive competence?NOT FOR DISTRIBUTIONMentalist rules:General rules:(application of CIP1 takes precedence over CIP2)(Sb-CIP1): IF a person looks at a demo of an action on an objectproducing an effect,THEN she knows that this action on that object has that effect.(Sb-CIP2): IF a person looks at a demo of an action on an objectproducing an effect,THEN she believes that the same action is more likely to producethe same effect on the same kind of (similarly looking) object thanon a different kind of object.(Sd-CIP): IF a person is asked to produce an effect, THEN she wants toproduce the effect.(dbA-CIP): IF a person wants to produce an effect, THEN she will usean object of which she knows/believes that it is most likely to producethat effect.Application to specific situations:(FB): The person looks at the demo of the dotted cup being shaken andproducing a rattling noise. The person knows that shaking the dotteddemo cup will produce a noise. One cup is more similar to the democup than the other. The person believes that the more similar cup ismore likely to produce the effect (Sb-CIP2, since 1 does not apply).The person is asked to use one of the other cups to produce theeffect. Person wants to produce the effect (Sd-CIP). Hence the personPerception, attention, and action:International Perspectives on Psychological Science (Volume1). Peter A. Frensch and Ralf Schwarzer (Eds). 2010.Published by Psychology Press on behalf of the International Union of Psychological Science.This proof is for the use of the author only. Any substantial or systematic reproduction,re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in anyform to anyone is expressly forbidden.15:58:17:03:10Page 253

Page 254254 <strong>Perner</strong>will use the cup of which she believes that it will more likely producethe effect (dbA-CIP), i.e., the other dotted cup.(TB-control): The person looks at demo for each individual cup, therefore(Sb-CIP1) knows that striped cup does but second dotted cupdoes not rattle when shaken. ... Hence the person will use the cup ofwhich she knows that it will more likely produce the effect (dbA-CIP), i.e., the other dotted cup.Behavior Rules:General rules (CIP1 takes precedence over CIP2):(SA-CIP1): IF a person looks at a demo of an action on objects producingan effectAND the person is asked to produce the effect with one ofthese objects,THEN the person is more likely to use an object on whichthe effect was shown when she looked than one that didn’tshow the effect when she looked.(SA-CIP2): IF a person looks at a demo of an action on an objectproducing an effectAND the person is asked to produce the effect with newobjects,THEN the person is more likely to use an object that issimilar to the demo object than one that is dissimilar.Application to specific situation:(FB): CIP1 does not apply, therefore, CIP2 applies and makes thecorrect prediction.(TB-control): CIP1 applies and makes the correct prediction.NOT FOR DISTRIBUTIONI also looked at most of the other studies mentioned in Seminar S-104(Buttelmann, Carpenter, & Tomasello, 2008, presented by Carpenter;Neumann, Thörmer, & Sodian, 2008; Poulin-Dubois & Chow, 2008; Träuble,Marinovic, & Pauen, 2008) and think them amenable to a very similar analysis.Their ingenious designs give us useful information about the CIPs infantsmust have available and how infants encode what they experience (situationsS and actions A) in a way that is also suitable for a mentalist approach (smartencoding). But these studies do not provide hard evidence in favour of mentalistCIPs over behavioral SA-CIPs. As I tried to point out in the secondsection (on Povinelli’s Challenge), such evidence is hard to come by andinvolves tests of generalizability. Lacking such evidence, let me investigatewhether we can find some help in plausibility arguments.Perception, attention, and action:International Perspectives on Psychological Science (Volume1). Peter A. Frensch and Ralf Schwarzer (Eds). 2010.Published by Psychology Press on behalf of the International Union of Psychological Science.This proof is for the use of the author only. Any substantial or systematic reproduction,re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in anyform to anyone is expressly forbidden.15:58:17:03:10Page 254

Page 256256 <strong>Perner</strong>procedure and reduce it to a quick reaction to the other’s response. When Iindicate my attack, I do not care what he thinks, I just wait for the firstglimpse of his movement to that side and react like a flash in moving to theother side, monitoring his reaction to my move, and plunging for a successfulstab or executing a counterfeint, if necessary. All this occurs in response tomonitoring his moves according to a behavior rule system pre-establishedthrough massive practice. In this example, the behavior rules are formedthrough practice following theoretical considerations about improving ourfencing prowess. But if the quick moves matter for survival and fitness, evolutionis better off establishing such behavioral strategies directly and not firsta flexible theory of mind on the basis of which one could devise suchbehavioral strategies.Looking at the findings on theory of mind in nonhuman animals, myimpression is that, whatever understanding of the mind they have, it is not theflexible kind. It is more likely an understanding based on behavior rules,limited to interactions that are particularly important for the species – forexample, food competition in chimpanzees. So I can agree with Povinelli andVonk (2004) that there is no evidence to date that speaks against the use ofbehavior rules (SA-CIPs). Given the evolutionary importance of such a system,it is plausible that we humans are genetically equipped with some basicprocedures or, at least, an acquisition system that preferentially picks uprelevant behavior rules by observation. My proposal, then, is that indirecttheory-of-mind tests pick up an understanding of social interaction in termsof behavior rules expressed in automatic, subconscious reactions. The directtests pick up later developing reasoned expectations and predictions, whichcan at times stand in contrast to the automatic reactions – as we have seen inthe case of expectant looking vs. answering questions.NOT FOR DISTRIBUTIONAre behavior rules an implicit theory of mind?I have made two points about precocious signs of understanding false belief. Iargued that these signs could well be based on behavior rules (SA-CIPs). Ialso pointed out that these signs all come from indirect tests, which, combinedwith the absence of such signs from direct tests, indicates the presenceof implicit knowledge. Can these two points be merged – that is, could knowledgebased on behavior rules be implicit knowledge of the mind?My best (most opportune) way of capturing the conversational meaning of“implicit” (similar to Dienes & <strong>Perner</strong>, 1999) is with the phrase “leavingsomething implicit” and explicate this as “getting at something without reallysaying so”. In this spirit we can view behavior rules as leaving the mindimplicit. For, they do get at the causal relations between S and A created bythe mind, without saying anything about the mind. Let us look again at thestandard scenario of an organism being in a situation S that has a desireinducing(response demand, purpose) and a belief-inducing (actual conditionsand instrumental facts) component. These components cause mentalPerception, attention, and action:International Perspectives on Psychological Science (Volume1). Peter A. Frensch and Ralf Schwarzer (Eds). 2010.Published by Psychology Press on behalf of the International Union of Psychological Science.This proof is for the use of the author only. Any substantial or systematic reproduction,re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in anyform to anyone is expressly forbidden.15:58:17:03:10Page 256

Page 257Anti-cognitivism infiltrates theory of mind 257states of desire (d) and instrumental beliefs (b) of what needs doing to fulfilthe desire. In turn these mental states are working together to cause an actionA. As a consequence, the workings of the mind create a causal link between Sand A. Which S causes which A depends on the mind. Behavior rules (SA-CIPs) try to capture the causal dependence of As on Ss without saying anythingabout the mind that creates those dependencies. But – and this isimportant – what they capture reflects the working of the mind. Behaviorrules provide an implicit theory of the mind– that is, they capture the workingsof the mind without mentioning the mind. Mentalism tries to capturethe same S-A dependencies but by being explicit about the intervening mind.Put in this way it may seem obvious and trivial. However, it has ideologicallyimportant implications.NOT FOR DISTRIBUTIONConclusionBehavior rules (SA-CIPs) are not mind-blind behaviorism. 17 In my understandingof behavior rules as SA-CIPs, they start from the same conceptualizationsof the environment (as S) and behavior (as A) as are used bymentalist inference procedures. Moreover, these rules capture the causaldependencies created by the mind. One certainly cannot say that an animal orinfant who uses behavior rules does not understand anything about the mind.The issue between behavior rules and mentalism is not one between understandingand no understanding of the mind. The issue is one about thestructure of that knowledge. The way to decide that issue is not by showinghow many S→A regularities are understood, but how understanding some ofthem might spread to others, as argued in the third section (“Going beyondPovinelli’s Challenge”). And that kind of evidence is hard to come by and isstill absent for non-human animals and human infants.Notes1 I unabashedly was inspired by Marshall Haith’s (1998) title “Who put the cog ininfant cognition?” But my use of “cog” is different. While he refers to the allegedthinking processes in infants, I mean the cognitive analysis of these mentalprocesses.2 The vivid booster-scoffer terminology was coined by Chandler, Fritz, and Hala(1989).3 Tomasello and Call (2006) are highly cautious and restrict themselves to talkingabout “seeing” short of claiming that chimps understand how seeing leads toknowing. What I have to say about knowing also applies to seeing insofar as seeingis seen as a mental state different from the physical relationship of looking (directingones unimpeded gaze at an object or event. Potential confusion can arise if“seeing” is equivocated between seeing as a synonym for “looking” and as amental state with intentional content like knowing. Two years later Call andTomasello (2008) find the available evidence had improved to warrant extendingthe claim to knowledge.4 I will use both terminologies to remind readers that these kinds of CIPs arePerception, attention, and action:International Perspectives on Psychological Science (Volume1). Peter A. Frensch and Ralf Schwarzer (Eds). 2010.Published by Psychology Press on behalf of the International Union of Psychological Science.This proof is for the use of the author only. Any substantial or systematic reproduction,re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in anyform to anyone is expressly forbidden.15:58:17:03:10Page 257

Page 258258 <strong>Perner</strong>behavior rules but also to minimize the behaviorist connotations and emphasizethat they are probably not conscious rules of the animal reflectively thinking: “ah,when he directs his gaze to . . .” etc”5 It also taints Premack and Woodruff’s (1978, p. 526) snappy defence of mentalism:“the ape could only be a mentalist . . . he is not smart enough to be abehaviorist.”6 These S→A CIPs are called “Behavior Rules” because part of the situation S isthe other individual’s behavior, which also needs to be observed for inferringfurther behavior, i.e., the action A.7 One could use “want” here. Two important points about the use of “want” in thiscontext: (1) Although a mental term is used, it is a quasi-“observable” fact of whatP wants, because one is told it in the story. (2) Although we classify “want” as amental state, it is an open question as to whether it is understood by children (oradults in routine cases) in this way. It can also be understood as a goal specification:he is going to get the object. Hence, I express it in this sort of neutral way.8 In the name of simplicity these arrows cover up much of the actual structure ofthe needed inference rules. For instance: IF P does not see an unexpected transfer,THEN he will think O is at the original location where he last saw it. It is notoriouslydifficult to find rules that cover our mentalist competence. Fortunately, thepresently relevant point is just that whatever rule is needed here, it can be adoptedin the formulation of behavior rules (see below).9 The rule underlying this arrow must stipulate something like: IF P wants to get O,THEN P will go to where he thinks O is. With further reasoning: Since he thinks itis in L1, we will arrive at the prediction that he will go to L1.10 Here too, a great simplification. The actual rule underpinning this arrow would besomething like: IF P is going to get O, THEN he will go to where he last saw O.The important general lesson is not the formulation of a specific behavioral rule,but that some rule is necessary for inferring either the future behavior or P’smental states and that the behavior can be inferred from the same observationalbasis as the mental states.11 My concern about this was raised when asked the question by Dan Povinelliduring the “Other Minds” conference at the University of Oregon in Eugene,September 2003.12 One may wonder how Call and Tomasello’s nonverbal false-belief test couldbe solved by behavior rules. Let us find out by following my recipe for applyingPovinelli’s Challenge: We need to first specify mentalist rules for solving thistask, e.g.:NOT FOR DISTRIBUTIONA person, who looks at an object in a box and does not look when this box isexchanged with an identical looking one, will think the object is now in the replacementbox. If the person is to mark the box with the object inside, the person willwant to mark the box where she thinks the object is, i.e., the now-empty replacementbox. The person marks the box on the left, so the object must be in the other box.This is a surprisingly great feat of reasoning for 4- or 5-year-old children, but abehavior rule approach does not make it more complicated. Only the first twosentences have to be reformulated:IF a person (who looks at an object in a box and does not look when this box isexchanged with an identical looking one) is supposed to mark the box with theobject inside, THEN the person will mark the box where the object was when shelooked inside, i.e., the now empty replacement box. ...13 Most impressively, due to sophisticated eye-tracking equipment, one can literallyPerception, attention, and action:International Perspectives on Psychological Science (Volume1). Peter A. Frensch and Ralf Schwarzer (Eds). 2010.Published by Psychology Press on behalf of the International Union of Psychological Science.This proof is for the use of the author only. Any substantial or systematic reproduction,re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in anyform to anyone is expressly forbidden.15:58:17:03:10Page 258

Page 259Anti-cognitivism infiltrates theory of mind 259see just how interested children at this age are in checking on another person’s eyegaze in relation to an ongoing event. Clearly, they keep carefully track of what theother is and is not looking at.14 In fact, I suspect that these studies can be better explained at a lower level than Iattempt in the text. They all show “smart encoding” by the infants, that is, infantsencode what they see (the S and As) in the same way a mentalist would. But onceencoded in that way, the looking times are governed not by what is expected tohappen but how similar the test situations are to what has occurred before whenthe relevant elements for smart encoding were present (see <strong>Perner</strong> & Ruffman 2005).15 A term familiar from the psychology of consciousness, e.g., implicit and explicitmemory. <strong>Perner</strong> and Clements (2000) draw extensive parallels to the implicitknowledge of blind-sight patients.16 Clements (1995, Expt. 5) varied belief-inducing situations to check whether theymake a larger difference for the indirect test (looking in expectation) than thedirect test, which would provide some evidence that indirect test performance isbased on behavior rules, in contrast to direct test performance. The interactionbetween situation type and type of test was in the expected direction but too weakto reach statistical significance.17 It remains debatable as to whether behaviorism is or is not mind-blind. It certainlydoesn’t like to talk about it. But presumably the regularities established by learning,which behaviorism tries to capture, reflect the workings of the mind.NOT FOR DISTRIBUTIONReferencesApperly, I. A. (2008, July). How does theory of mind change from children to adults?Paper presented at the XXIX International Congress of Psychology, Berlin.Apperly, I. A., & Butterfill, S. A. (2008). Do humans have two systems to track beliefsand belief-like states? Unpublished manuscript, Department of Psychologty, Universityof Birmingham.Buttelmann, D., Carpenter, M., & Tomasello, M. (2008). Sixteen-month-olds showfalse belief understanding in an active helping paradigm. Unpublished manuscript,Department of Developmental and Comparative Psychology, Max Planck Institutefor Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig.Call, J., & Tomasello, M. (1999). A nonverbal false belief task: The performance ofchildren and great apes. Child Development, 70(2), 381–395.Call, J., & Tomasello, M. (2008). Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind?30 years later. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 12, 187–192.Chandler, M. J., Fritz, A. S., & Hala, S. M. (1989). Small scale deceit: Deception as amarker of 2-, 3- and 4-years-olds’ early theories of mind. Child Development, 60,1263–1227.Clements, W. A. (1995). Implicit theories of mind. Unpublished doctoral dissertation,University of Sussex.Clements, W. A., & <strong>Perner</strong>, J. (1994). Implicit understanding of belief. CognitiveDevelopment, 9, 377–397.Dienes, Z., & <strong>Perner</strong>, J. (1999). A theory of implicit and explicit knowledge [Targetarticle]. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 22, 735–755.Doherty, M. J., & <strong>Perner</strong>, J. (1998). Metalinguistic awareness and theory of mind: Justtwo words for the same thing? Cognitive Development, 13, 279–305.Garnham, W. A., & <strong>Perner</strong>, J. (2001). Actions really do speak louder than words – butonly implicitly: Young children’s understanding of false belief in action. BritishJournal of Developmental Psychology, 19, 413–432.Perception, attention, and action:International Perspectives on Psychological Science (Volume1). Peter A. Frensch and Ralf Schwarzer (Eds). 2010.Published by Psychology Press on behalf of the International Union of Psychological Science.This proof is for the use of the author only. Any substantial or systematic reproduction,re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in anyform to anyone is expressly forbidden.15:58:17:03:10Page 259

Page 260260 <strong>Perner</strong>Garnham, W. A., & Ruffman, T. (2001). Doesn’t see, doesn’t know: Is anticipatorylooking really related to understanding of belief? Developmental Science, 4, 94–100.Haith, M. M. (1998). Who put the cog in infant cognition? Is rich interpretation toocostly? Infant Behavior and Development, 21, 167–179.Hare, B., Call, J., Agnetta, B., & Tomasello, M. (2000). Chimpanzees know whatconspecifics do and do not see. Animal Behaviour, 59, 771–785.Hare, B., & Tomasello, M. (2001). Do chimpanzees know what conspecifics know?Animal Behaviour, 61, 139–151.Heyes, C. M. (1998). Theory of mind in nonhuman primates. Behavioral and BrainSciences, 21, 101–148.Hogrefe, J., Wimmer, H., & <strong>Perner</strong>, J. (1986). Ignorance versus false belief: A developmentallag in attribution of epistemic states. Child Development, 57, 567–582.Low, J. (2007). Complements are necessary but insufficient: Roes of anticipatory eyegaze and cognitive flexibility for false-belief understanding. Unpublished manuscript,School of Psychology, Victoria University of Wellington.Neumann, A., Thörmer, C., & Sodian, B. (2008, July). False belief understandingin 18-month-olds’ anticipatory looking behavior: An eye-tracking study. Paperpresented at the XXIX International Congress of Psychology, Berlin.Onishi, K. H., & Baillargeon, R. (2005). Do 15-month-old infants understand falsebeliefs? Science, 308, 255–258.<strong>Perner</strong>, J., & Clements, W. A. (2000). From an implicit to an explicit theory of mind. InY. Rossetti & A. Revonsuo (Eds.), Beyond dissociations: Interaction between dissociatedimplicit and explicit processing (pp. 273–293). Amsterdam: JohnBenjamins.<strong>Perner</strong>, J., Lang, B., & Kloo, D. (2002). Theory of mind and self-control: More than acommon problem of inhibition. Child Development, 73, 752–767.<strong>Perner</strong>, J., Leekam, S. R., & Wimmer, H. (1987). Three-year olds’ difficulty with falsebelief: The case for a conceptual deficit. British Journal of Developmental Psychology,5, 125–137.<strong>Perner</strong>, J., & Ruffman, T. (2005). Infants’ insight into the mind: How deep? Science,308, 214–216.<strong>Perner</strong>, J., & Wimmer, H. (1988). Misinformation and unexpected change: Testing thedevelopment of epistemic-state attribution. Psychological Research, 50, 191–197.Piaget, J. (1971). Structuralism. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. (First published asLe Structuralisme, by Presses Universitaire de France, Paris, 1968).Piaget, J. (1972). The principles of genetic epistemology. London: Routledge & KeganPaul. (First published as L’epistemologie génétique, by Presses Universitaire deFrance, Paris, 1970.)Poulin-Dubois, D., & Chow, V. (2008). Seeing is believing: Infants attribute beliefs onlyto a reliable looker. Unpublished manuscript, Concordia University, Montreal,Canada.Poulin-Dubois, D., Sodian, B., Metz, U., Tilden, J., & Schoeppner, B. (2007). Out ofsight is not out of mind: Developmental changes in infants’ understanding ofvisual perception during the second year. Journal of Cognition and Development,8, 401–425.Povinelli, D. J., & Eddy, T. J. (1996). What young chimpanzees know about seeing.Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 61, 1–152.Povinelli, D. J., & Vonk, J. (2003). Chimpanzees minds: Suspiciously human? Trends inCognitive Sciences, 7, 157–160.NOT FOR DISTRIBUTIONPerception, attention, and action:International Perspectives on Psychological Science (Volume1). Peter A. Frensch and Ralf Schwarzer (Eds). 2010.Published by Psychology Press on behalf of the International Union of Psychological Science.This proof is for the use of the author only. Any substantial or systematic reproduction,re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in anyform to anyone is expressly forbidden.15:58:17:03:10Page 260

Page 261Anti-cognitivism infiltrates theory of mind 261Povinelli, D. J., & Vonk, J. (2004). We don’t need a microscope to explore the chimpanzee’smind. Mind & Language, 19, 1–28.Premack, D., & Woodruff, G. (1978). Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind?Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 1, 516–526.Ruffman, T., Garnham, W., Import, A., & Connolly, D. (2001). Does eye gaze indicateimplicit knowledge of false belief? Charting transitions in knowledge. Journal ofExperimental Child Psychology, 80, 201–224.Scott, R. M., & Baillargeon, R. (2008, July). Infant’s understanding of false beliefsabout the location, identity, and properties of objects. Paper presented at the XXIXInternational Congress of Psychology, Berlin.Sirois, S., & Jackson, I. (2007). Social cognition in infancy: A critical review ofresearch on higher order abilities. European Journal of Developmental Psychology,4, 46–64.Southgate, V. (2008, September). Attributions of false belief in infancy. Invited presentationat the EPS Research Workshop on theory of mind: A workshop in celebrationof the 30th anniversary of Premack & Woodruff’s seminal paper, “Does thechimpanzee have a Theory of Mind? (BBS 1978), University of Nottingham.Southgate, V., Senju, A., & Csibra, G. (2007). Action anticipation through attributionof false belief by 2-year-olds. Psychological Science, 18, 586–592.Surian, L., Caldi, S., & Sperber, D. (2007). Attribution of beliefs by 13-month-oldinfants. Psychological Science, 18, 580–586.Tomasello, M., & Call, J. (2006). Do chimpanzees know what others see – or onlywhat they are looking at? In S. Hurley & M. Nudds (Eds.), Rational animals(pp. 371–384). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.Träuble, B., Marinovic, V., & Pauen, S. (2008, July). Early understanding of false beliefrule-based or mentalistic? Paper presented at the XXIX International Congress ofPsychology, Berlin.Wellman, H. M., Cross, D., & Watson, J. (2001). Meta-analysis of theory of minddevelopment: The truth about false belief. Child Development, 72, 655–684.Whiten, A. (1996). When does smart behavior-reading become mind-reading? InP. Carruthers & P. K. Smith (Eds.), Theories of theories of mind (pp. 277–292).Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.Wimmer, H., & Mayringer, H. (1998). False belief understanding in young children:Explanations do not develop before predictions. International Journal ofBehavioral Development, 22(2), 403–422.Wimmer, H., & <strong>Perner</strong>, J. (1983). Beliefs about beliefs: Representation and constrainingfunction of wrong beliefs in young children’s understanding of deception.Cognition, 13, 103–128.NOT FOR DISTRIBUTIONPerception, attention, and action:International Perspectives on Psychological Science (Volume1). Peter A. Frensch and Ralf Schwarzer (Eds). 2010.Published by Psychology Press on behalf of the International Union of Psychological Science.This proof is for the use of the author only. Any substantial or systematic reproduction,re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in anyform to anyone is expressly forbidden.15:58:17:03:10Page 261

Page 262NOT FOR DISTRIBUTIONPerception, attention, and action:International Perspectives on Psychological Science (Volume1). Peter A. Frensch and Ralf Schwarzer (Eds). 2010.Published by Psychology Press on behalf of the International Union of Psychological Science.This proof is for the use of the author only. Any substantial or systematic reproduction,re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in anyform to anyone is expressly forbidden.15:58:17:03:10Page 262