Management Plan - National Estuarine Research Reserve System

Management Plan - National Estuarine Research Reserve System

Management Plan - National Estuarine Research Reserve System

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

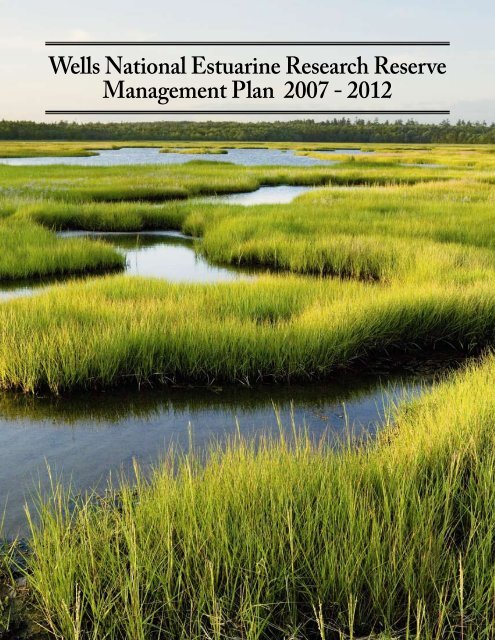

Wells <strong>National</strong> <strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong><strong>Management</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> 2007 - 2012

AcknowledgmentsThis document was prepared and printed with funds from Grant Award Number NA04NOS4200098,<strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>s Division, Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource <strong>Management</strong> (OCRM), <strong>National</strong> OceanService (NOS) of the <strong>National</strong> Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), U.S. Department ofCommerce. Additional funds provided by Laudholm Trust.The Wells <strong>National</strong> <strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> was prepared by the staff of the Wells<strong>Reserve</strong> with input from its Advisory Committees—including those for Buildings, Education, Stewardship,and <strong>Research</strong>—and the members of the <strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>Management</strong> Authority. Guidance from NOAA wasprovided by Program Officer Doris Grimm of the <strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>s Division. The principal contributorsincluded: Chris Feurt, Coastal Training Program Coordinator; Laura Lubelczyk, Education Coordinator(2006); Sarah Jolly, Education Coordinator; Tin Smith, Stewardship Coordinator; Michele Dionne,<strong>Research</strong> Coordinator; Nancy Viehmann, Volunteer Coordinator; Scott Richardson, CommunicationsCoordinator; Sue Bickford, Natural Resource Specialist; Cayce Dalton, <strong>Research</strong> and Education Associate(graphic design); Matthew McBride, GIS Specialist; and Paul Dest, <strong>Reserve</strong> Manager (editor).

Table of ContentsAcknowledgments.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . iiI. Overview .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2Introduction to the <strong>Reserve</strong> .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2Part of a <strong>National</strong> <strong>System</strong> .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2Purpose and Scope of the <strong>Plan</strong> .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2Education .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3<strong>Research</strong> .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4Stewardship .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4Boundary and Land Acquisition. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4Facilities .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5Administration .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6Volunteers. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6Site Profile .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6II. Introduction. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8The Value of Estuaries .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8The NERR <strong>System</strong>.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8Mission.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8Goals. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9<strong>National</strong> <strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>System</strong> Strategic Goals 2003 – 2008.. . . . 9<strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>System</strong> Strategic <strong>Plan</strong> Mission (revised 2006) .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9<strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>System</strong> Strategic <strong>Plan</strong> Goals (revised 2006).. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9Biogeographic Regions. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9<strong>Reserve</strong> Designation and Operation.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11NERRS Administrative Framework .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11<strong>Research</strong> and Monitoring <strong>Plan</strong> [§921.50].. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11<strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>System</strong> <strong>Research</strong> Goals .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11<strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>System</strong> <strong>Research</strong> Funding Priorities.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12<strong>System</strong>-Wide Monitoring Program.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12Education <strong>Plan</strong> [§921.13(a)(4)]. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13<strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>System</strong> Education Mission and Goals.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14<strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>System</strong> Education Objectives .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14<strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>System</strong> Coastal Training Program.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14III. Wells NERR Setting. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18Physical Setting—Overview .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18Geography.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18Geology .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19Hydrology.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19Climate. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 20Vegetation and Habitats .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21Upland Fields and Forests.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21Wetlands.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21Beach and Dune .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22Table of Contentsiii

Intertidal.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22Key Species. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22Flora.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22Invertebrate Fauna.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23Vertebrate Fauna.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23Cultural History and Community Setting .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24History.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24Community Growth and Land Use .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25Population Growth.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26Land-Use <strong>Plan</strong>ning. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26Marine-Related Activities. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26Tourism and Travel.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26Water Quality.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26Impacts Affecting the <strong>Reserve</strong>.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26IV. Strategic <strong>Plan</strong> 2007 - 2012 .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30Vision .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30Mission.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30Strategic Goals.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30Strategic Objectives.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30Education .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30<strong>Research</strong> .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31Stewardship .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31Administration .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31Boundary and Acquisition .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31Facilities .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31Public Access .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31Communications. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31Volunteers. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31V. Accomplishments 2000 - 2006.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34Facilities, Exhibits and Trails.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34Interpretive Education. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34Coastal Training Program.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35<strong>Research</strong> .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36Stewardship .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38Public Information.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40Partnerships and Community Engagement .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40Volunteer Programs .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40<strong>Plan</strong>ning Documents .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40VI. Administrative <strong>Plan</strong>.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42Introduction .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42Objective and Strategies .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42Objective.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42Strategies .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42Administrative Structure: <strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>Management</strong> Authority.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42ivWells <strong>National</strong> <strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>

Representation on the <strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>Management</strong> Authority. . . . . . . . . . . 42Maine Department of Conservation.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43Town of Wells .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43Laudholm Trust. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .43Maine State <strong>Plan</strong>ning Office/Maine Coastal Program.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43U.S. Department of Commerce, NOAA .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43Interagency Memoranda of Understanding.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 43Other Partner Roles and Responsibilities .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44NOAA’s Roles and Responsibilities. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45Laudholm Trust Partnership. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45<strong>National</strong> Historic Preservation Act. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46Maine Coastal Program and Maine Sea Grant College Program.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46<strong>Reserve</strong> Staff Responsibilities.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46In-Kind Staff Roles and Responsibilities .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47Volunteer Roles and Responsibilities. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47Wells <strong>Reserve</strong> Advisory Committees.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48Wells <strong>Reserve</strong> Program Integration Strategy.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48VII. Facilities and Construction <strong>Plan</strong>. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52Introduction .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52Objective and Strategies .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52Objective.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52Strategies .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52Laudholm Farm: Main Campus Facilities and Forest Learning Shelter .. . . . . . . . . 53Main Farmhouse (includes ell and woodshed).. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53Barn Complex (includes auditorium and library).. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54Maine Coastal Ecology Center (MCEC) .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54Ice House .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54Water Tower. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54Gazebo/Well House.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55Forest Learning Shelter .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55Laudholm Farm: <strong>Reserve</strong>d Life Estate Buildings .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55Manure Shed (circa 1905).. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56Sheep Barn (circa 1890-1900) .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56Farmer’s Cottage and Wood Shed (circa 1830-1850) .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 56Killing House (early 1900’s) .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 57Chick Brooder Building / Little Residence (circa 1916).. . . . . . . . . . . . . 57Bull Barn and Silo (early 1900’s) .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 57Auto Garages (1907/1920’s).. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 57Brooder House.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 57Other Buildings .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 57Facilities of the Alheim Property. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 58Alheim Commons (2006).. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 58Alheim Commons Studio (circa 1900) .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 58Ranch-style House (circa 1960’s). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 58Table of Contents

In-holding Properties and Renovation of Buildings. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5819 th Century Lord Farmhouse.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 59VIII. Public Access <strong>Plan</strong> .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 62Introduction .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 62Objective and Strategies .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 62Objective.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 62Strategies .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 62Audiences, Hours of Operation and Fees.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 62Trail Hours.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63Fees .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63Points of Access to the <strong>Reserve</strong>.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63Permitted Activities — Lands. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 64Permitted Activities — Facilities .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65Wildlife Sanctuary Designation .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65Rules and Regulations.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66IX. Education and Outreach <strong>Plan</strong>.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68Introduction .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68Objectives and Strategies.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68Objective 1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68Strategies .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68Objective 2. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68Strategies .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68Objective 3. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 68Strategies .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 69Objective 4. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 69Strategies .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 69Guiding Principles.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 69Geographic Scope .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 69Coastal Training Program.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70K–12 Education.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71Field-and-Lab School Programs .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71Field-Based School Programs.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72Day Camps .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72Teacher/Educator Training .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72Docent Naturalist Training.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73Public Programs.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73Exhibits. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 75Trail/Site Interpretation.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 75Higher Education (including internships and mentorships).. . . . . . . . 75Off-site Programs and Community Outreach .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 75Citizen Monitoring.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 75Coastal Resource Library.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 76X. <strong>Research</strong> and Monitoring <strong>Plan</strong>.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 78Introduction .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 78viWells <strong>National</strong> <strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>

Objectives and Strategies.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 78Objective 1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 78Strategies .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 78Objective 2. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 78Strategies .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 78Objective 3. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79Strategies .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79NERR <strong>System</strong> <strong>Research</strong> Overview .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 79<strong>System</strong>-wide <strong>Research</strong> Funding Priorities.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 80Graduate <strong>Research</strong> Fellowships .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 80<strong>System</strong>-wide Phased Monitoring .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 80<strong>System</strong>-wide Monitoring Program. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 81Abiotic Variables .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 81Biological Monitoring.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 81Land Use and Habitat Change.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 81Wells <strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>Research</strong> Themes.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 82<strong>Estuarine</strong> Water Quality. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 82Salt Marsh Habitats and Communities. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 82Habitat Value for Fish, Shellfish and Birds.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 83Salt Marsh Degradation and Restoration .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 83Field <strong>Research</strong> Sites .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 83Academic and Institutional Partnerships.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 83Government Partnerships.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 84Mentoring and Internships .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 85Information Dissemination.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 85Conferences and Workshops.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 85Site Profile.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 85XI. Stewardship <strong>Plan</strong> .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 88Introduction .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 88Goals and Objectives .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 88Objective 1. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 88Strategies .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 88Objective 2. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89Strategies .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89Objective 3. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89Strategies .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89Objective 4. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89Strategies .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89Site-Based Stewardship.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89<strong>Management</strong> Framework .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89Environmental and Public Safety Laws .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 90<strong>Management</strong> Zones. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91Public and Administrative Zone.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91Active <strong>Management</strong> Zone.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91Conservation Zone .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 92Table of Contentsvii

Protected Zone.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 92Resource <strong>Management</strong> Projects.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 92Deer Population Control.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 92Invasive <strong>Plan</strong>t Control.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 92New England Cottontail Habitat <strong>Management</strong>.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93Open Field <strong>Management</strong>. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93Drakes Island Restoration Monitoring .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93Potential Restoration Projects .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93Harbor Park .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 94Beaches and Dunes .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 94Wells Harbor.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 94Community-Based Stewardship.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 95Watershed Protection .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 95Land Conservation and GIS Center .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 95Habitat Restoration.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 96XII. <strong>Reserve</strong> Boundary and Acquisition <strong>Plan</strong>.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 98Introduction .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 98Objective and Strategies .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 98Objective.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 98Strategies .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 98Proposed Changes to the <strong>Reserve</strong> and Acquisition Boundary (Section 315).. . . . . . . . 99Justification for Changes to the Boundary.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100Ecology. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 102Maintain the Integrity of Coastal Watersheds .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 102Protecting Water Quality .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 102Habitat Protection.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 102Education, Outreach, and Training.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103<strong>Research</strong> and Monitoring .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103Evaluation Criteria.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 104Priorities for Acquisition.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 104Specific In-holdings and Adjacent Parcels.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 104Focus Areas on Little River and Webhannet River .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 105Focus Area #1 — Little River Watershed .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 105Focus Area #2 — Webhannet River Watershed.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 106Note on Sections of Watersheds Outside Town of Wells.. . . . . . . . . 106Strategies and Methods for Acquisition. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 106Evaluating Conservation Lands.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 106Means of Acquisition .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 106Approaches to Land Protection. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 106Fee Simple Purchase .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 106Conservation Easement. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107Donations.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107Other Methods. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107Funds for Land Acquisition.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107Holding Title to Acquired Lands.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107viiiWells <strong>National</strong> <strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>

XIII. Volunteer <strong>Plan</strong>.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 110Introduction .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 110Objective and Strategies .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 110Objective.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 110Strategies .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 110Volunteers.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 110Volunteer Positions.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 110Volunteer Recruitment .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 110Volunteer Training .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 111Evaluating Volunteers .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 111Rewarding Volunteer Involvement.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 111XIV. Communications <strong>Plan</strong>.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 114Introduction .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 114Objective and Strategies .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 114Objective.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 114Strategies .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 114Print Publications .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 114Electronic Communications.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 114Media Relations.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 114Events, Presentations, and Displays.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 115Tracking Success.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 115Appendix A: Memoranda of Understanding.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 120Appendix A.1: NOAA and RMA.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 120Appendix A.2: USFWS and RMA. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 124Appendix A.3: Maine Dept. Conservation/BPL and RMA - Laudholm Beach andUplands. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 128Appendix A.4: Maine Dept. Conservation/BPL and RMA - Submerged Lands.. 132Appendix A.5: Town of Wells and RMA.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 134Appendix A-6: Laudholm Trust and RMA.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 136Appendix B: Conservation Easements .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 142Appendix B-1: Conservation Easement Deed on Laudholm Farm .. . . . . . . . . . . . 142Appendix B-2: Conservation Easement Deed at Wells Harbor. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 154Appendix C: State of Maine Legislation .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 166Appendix C-1: Act to Establish Wells NERR .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 166Appendix C-2: Act to Amend the Laws Regarding the Location of Wells NERR... 172Appendix D: Rules for Public Use .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 176Appendix E: Natural Resource Laws.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 184Appendix F: Federal Regulations—NERRS .. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 194Appendix G: CZMA—Section 315.. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 222Appendix H: Wells NERR Acreage Comparisons.. . . . . . . . . . . . . 227Table of Contentsix

Wells <strong>National</strong> <strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>

xiiWells <strong>National</strong> <strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>

I. Overview

I. OverviewIntroduction to the <strong>Reserve</strong>The Wells <strong>National</strong> <strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>was designated a <strong>National</strong> <strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Research</strong><strong>Reserve</strong> by the <strong>National</strong> Oceanic and AtmosphericAdministration (NOAA) in 1984.The Wells <strong>Reserve</strong> is the only NERR in Maine andone of two NERRs located in NOAA’s AcadianBiogeographic Region. It is situated on the southernMaine coast, and comprises 2,250 acres of saltmarshes, beaches, dunes, upland fields and forests,riparian areas and submerged lands within thewatersheds of the Little River, Webhannet River,and Ogunquit River. Parcels of conserved landowned by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Townof Wells, the Maine Department of Conservationand the Wells <strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>Management</strong> Authoritymake up the <strong>Reserve</strong>.In addition to the conservation land, the Wells<strong>Reserve</strong> includes two building campuses that supportthe <strong>Reserve</strong>’s mission: 1) Laudholm Farm, acluster of buildings on the <strong>National</strong> Register ofHistoric Places, that serves as the center for visitorsand for the research, education, and stewardshipprograms; and 2) the Alheim Commons, a propertythat includes two facilities that house visitingscientists, educators, and resource managers.Part of a <strong>National</strong> <strong>System</strong>The Wells <strong>Reserve</strong> is part of the <strong>National</strong> <strong>Estuarine</strong><strong>Research</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>System</strong> (NERRS). Created bythe Coastal Zone <strong>Management</strong> Act of 1972, theNERRS provides a network of representative estuarineecosystem areas suitable for long-term research,education and stewardship. More than one millionacres of estuarine lands and waters are currentlyincluded within the 27 federally designated reserves.Administered by the <strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>s Division(ERD) at the <strong>National</strong> Oceanic and AtmosphericAdministration (NOAA), the reserve system is afederal-state partnership. NOAA and coastal statepartners collaborate to set common priorities andto develop system-wide programs. Additionally,NOAA provides support for state partners andnational cohesion. State partners carry out locallyrelevant and nationally significant programs atindividual reserves and provide day-to-day managementof resources and programs.Individual reserves represent specific biogeographicregions of the United States. A biogeographicregion is an area with similar plants, animals, andclimate. There are 11 major biogeographic regionsaround the coast and 29 sub-regions (see FigureII.3). The <strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>System</strong> is designed to includesites representing all 29 biogeographic subregions,with additional sites representing different types ofestuaries. The <strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>System</strong> currently represents18 of those sub-regions. Each reserve implementseducation, research, and stewardship programsrelevant to its bioregion and to the state in whichit is located.Purpose and Scope of the <strong>Plan</strong>This is the third edition of the Wells <strong>National</strong><strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>:the first <strong>Plan</strong> was approved by NOAA in April1985; the second in June 1996.Since the last management plan, the Wells <strong>Reserve</strong>has implemented several system-wide programs,acquired two key parcels of land, changed itsboundary, and constructed needed facilities. Inaddition to accomplishing core programs, the<strong>Reserve</strong> established the Geographic Information<strong>System</strong> Center to support its education, research,and stewardship activities; launched a highlysuccessful Coastal Training Program to reachdecision-makers; initiated outreach programs forsouthern Maine conservation organizations; andimplemented major components of the <strong>System</strong>-Wide Monitoring Program. It acquired the 27-acreAlheim property and the 2½-acre Lord Parcel, andchanged its boundary to include more of the watershedareas of the <strong>Reserve</strong>. The <strong>Reserve</strong> built theMaine Coastal Ecology Center, new interpretiveexhibits, the Alheim Commons dormitory, and theForest Learning Shelter, and equipped and openedthe Coastal Resource Library.Wells <strong>National</strong> <strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>

This 3 rd edition of the <strong>Management</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> serves asthe primary guidance document for the operationof the Wells <strong>Reserve</strong>’s core and system-wide programsin research and monitoring, education andcoastal training, and resource management andstewardship. In addition, it provides guidance onthe acquisition of land to be added to the <strong>Reserve</strong>,and on the construction and renovation of buildingsand exhibits that support NERR programs.The <strong>Management</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> also guides the <strong>Reserve</strong> inimportant related programs, such as volunteerismand outreach to communities to encourage stewardshipof coastal resources in southern Maine.This <strong>Plan</strong> includes important background on the<strong>Reserve</strong>, including the setting, history, rules andregulations, cooperative agreements between the<strong>Reserve</strong> and its partners, and other informationThe heart of this <strong>Management</strong> <strong>Plan</strong> is composedof a description of our major programs, and theirobjectives and strategies for the next five years.Here is an overview of our major program areas:EducationThe goal of the education program is to design,implement, and support quality science-basedprograms that promote stewardship of the Gulf ofMaine and coastal environments through understandingand appreciation of ecological systems andprocesses.The <strong>Reserve</strong> is a regional center for education,training, and outreach on coastal, estuarine andwatershed ecology. Education programs at theWells <strong>Reserve</strong> inform and engage audiences on thefunctions and values of coastal ecosystems and waysto manage those systems’ sustainability. Educationprograms translate research into readily availableinformation, promote stewardship of coastalresources, and provide a conduit for research findingsto coastal decision makers and communities.Current and future education focus areas for the<strong>Reserve</strong> include: the Docent Program; InterpretiveWalks; Events; Lectures; Childrens’ Programs;Internships and Field Studies; School Programs;Figure I.1. A view of the estuarine section of Branch Brook. Photo Ward Feurt.<strong>Management</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>: Overview

Exhibits and Interpretive Trails; Publications; andOutreach to Community Groups and Schools.A major component of the <strong>Reserve</strong>’s educationalefforts is the Coastal Training Program. Throughthis system-wide initiative, the Wells <strong>Reserve</strong>provides decision-makers in Maine communitieswith science-based information to encourage thewise stewardship of coastal resources. This is donethrough workshops, seminars, conferences, and theestablishment of community partnerships, as wellas the development and distribution of informationon appropriate topics.<strong>Research</strong>The Wells <strong>Reserve</strong> research program studies andmonitors natural and human-induced change inGulf of Maine estuaries, coastal habitats, andadjacent coastal watersheds, and produces sciencebasedinformation needed to protect, sustain, orrestore them.<strong>Reserve</strong> scientists participate in research, monitoring,planning, management, and outreach activitieslocally, regionally and nationally. The program supportsfield research along Maine’s southwest coastfrom the Kennebec River to the Piscataqua River.Current and future focus areas for the research programinclude: <strong>Estuarine</strong> Water Quality; Salt MarshHabitats and Natural Communities; Distributionand Abundance of Fish and Shellfish; Salt MarshDegradation and Restoration Science.A major program component of the Wells <strong>Reserve</strong>is the <strong>System</strong> Wide Monitoring Program (SWMP)and its links to the Integrated Ocean Observing<strong>System</strong>. This program monitors for various waterquality parameters, weather, biological change, andlandscape change.StewardshipThe Wells <strong>Reserve</strong> strives to exemplify wise coastalstewardship through sound natural resource managementwithin its boundary and through its partnershipsin the communities of southern Maine.The diverse habitats encompassed by the Wells<strong>Reserve</strong> support distinct plant and animal communitiesthat require specific stewardship approaches.Woodlands and fields are fairly resilient to humanuse, while salt marshes, sand dunes, vernal pools,and certain upland habitats are more sensitive tohuman impacts. Some parts of the <strong>Reserve</strong> arerelatively pristine, while other areas—includingearly successional farm fields—are under ecologicalstress associated with past land use practices and thespread of invasive species. Rare native plants andanimals require specific management approaches.Deer population levels have contributed to thespread of invasive plants and human health issuesassociated with Lyme disease. Because of its habitatdiversity, and management challenges, the Wells<strong>Reserve</strong> natural environments serve as an excellentlocation to experiment with various innovativeresource management activities, to conduct researchand offer education programs.The <strong>Reserve</strong> is also active in promoting coastalstewardship in the communities of southern Maine.Through its community-based stewardship programefforts, the <strong>Reserve</strong> encourages individuals andorganizations to recognize connections betweenland-use actions and environmental quality and totake responsibility for protecting coastal watersheds.This is accomplished through working with groupsand municipalities on watershed management, landconservation planning and assistance and habitatrestoration.Boundary and Land AcquisitionThe Wells <strong>Reserve</strong> seeks to permanently conservelands necessary to protect <strong>Reserve</strong> resources,thereby ensuring a stable environment for researchand education. One goal over the next five years isto broaden the <strong>Reserve</strong>’s representation of coastalecosystems beyond the salt marshes and immediatelyadjacent uplands to include coastal watershedareas. Over the next five years the <strong>Reserve</strong> willidentify and prioritize parcels of land within theWebhannet River, Little River, and Ogunquit Riverwatersheds that best meet the evaluation criteria setout in this <strong>Management</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>. The Wells <strong>Reserve</strong>Wells <strong>National</strong> <strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>

Figure I.2. The historic farmhouse serves as the <strong>Reserve</strong>’s Visitor Center.will seek to accomplish the following: 1) work withpartners including U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service,Town of Wells, Kennebunk/Kennebunkport/WellsWater District, Great Works Regional Land Trustand the Laudholm Trust to develop conservationstrategies and funding; 2) cooperate with partnersto maximize the protection of natural resourcesof highest value to the <strong>Reserve</strong>’s programs; and 3)develop and implement the best options to permanentlyconserve identified lands.FacilitiesThe Wells <strong>Reserve</strong> strives to provide staff and collaboratorswith safe, comfortable buildings andequipment required to accomplish <strong>Reserve</strong> education,research, and stewardship program strategies;to provide visitors with facilities in which to learnabout coastal ecosystems; and to preserve thebuildings’ architectural heritage in the context ofaccommodating 21st century uses as an estuarineresearch and education center.<strong>Reserve</strong> facilities used for these purposes are in twolocations: Laudholm Farm, a complex of more thana dozen historic buildings and one new building;and the Alheim Property, an adjacent parcel holdingthree buildings one-half mile from LaudholmFarm.<strong>Management</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>: Overview

The Wells <strong>Reserve</strong> requires specific facilities for abroad range of programs and activities. Facilitiesneeded include offices for staff and visiting educatorsand researchers; laboratories for scientists andstudents; a maintenance and repair shop; storageareas; interpretive exhibit areas; classrooms; a giftshop; a welcome area; a public library; meetingrooms; spaces for public events; and living spaces forvisiting scientists, educators, and natural resourcemanagers.AdministrationThe Wells <strong>Reserve</strong> is unique in the NERR <strong>System</strong>,as it is the only <strong>Reserve</strong> unaffiliated with a Statenatural resource agency or university. Instead, it isa public/private partnership whose administrativeoversight is vested in the <strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>Management</strong>Authority (RMA). This independent state agencywas established in 1990 to support and promotethe interests of the Wells <strong>Reserve</strong>. The RMA hasa Board of Directors composed of representativeshaving a property, management, or programinterest in the Wells <strong>Reserve</strong>. RMA membersrepresent the Maine Department of Conservation,the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Town ofWells, Laudholm Trust, the Maine State <strong>Plan</strong>ningOffice, and the <strong>National</strong> Oceanic and AtmosphericAdministration. A Governor-appointed scientistwith an established reputation in the field of marineor estuarine research also serves on the RMA. TheManager reports to the RMA, which has quarterlyboard meetings.VolunteersOne of the great strengths of the Wells <strong>Reserve</strong>is its spirit of volunteerism, which was essentialto the establishment of the <strong>Reserve</strong>. The <strong>Reserve</strong>’svolunteer programs engage a diverse corps of morethan 400 people who contribute over 15,000 hoursannually to advancing the Wells <strong>Reserve</strong>’s mission.Volunteer programs are directed through a closecollaboration with Laudholm Trust.The Wells <strong>Reserve</strong> volunteers fill many roles andaccomplish many tasks. They greet visitors, answerphones, teach school groups, tend the grounds,patrol trails, scrape and paint, proofread, domailings, enter research data, distribute programinformation, lead nature walks, develop educationalmaterials, assist ad hoc committees, monitorwater quality and raise funds. Many volunteersserve on standing advisory committees that meetregularly to guide <strong>Reserve</strong> staff on research, education,building, library and resource managementprograms and issues. In addition, volunteers areinvolved with projects through collaborationswith the Rachel Carson <strong>National</strong> Wildlife Refuge,Maine Sea Grant, local schools, businesses, YorkCounty Audubon Society and other partners.Over the next five years, the Wells <strong>Reserve</strong> willcontinue to engage and cultivate volunteers inour programs, as their involvement is key to the<strong>Reserve</strong>’s continued success.Site ProfileThe Wells <strong>National</strong> <strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>Site Profile is a separate document that providesdetailed information about the <strong>Reserve</strong> and its naturalresources. Published in January 2007, the 326-page book contains information on the <strong>Reserve</strong>’sphysical and biological resources. It includes plantand animal species lists, past research and monitoringprojects, and current and future research needs.The Site Profile is an excellent reference document,which is aimed at researchers and resource managerscarrying out projects in south coastal Maine.It also helps guide research projects at the Wells<strong>Reserve</strong> and informs decisions on land and waterstewardship within the <strong>Reserve</strong>’s boundaries and inits watersheds.Wells <strong>National</strong> <strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>

II. Introduction

II. IntroductionThe Value of EstuariesEstuaries are coastal areas where salt water fromthe sea mixes with fresh water from rivers. Theycomprise some of the most productive ecosystemson Earth. Whether they are called a bay, a river,a sound, a bayou, a harbor, an inlet, a slough, ora lagoon, estuaries are the transition between theland and the sea.Estuaries are dynamic ecosystems that provideessential habitat for plant and animal life. Theyserve as nurseries for numerous plant and animalspecies, some of which humankind depends on.Wetlands on the shores of estuaries protect humancommunities from flooding. They act as buffersagainst coastal storms that would otherwise flooddeveloped inland areas.Creating a greater understanding of estuaries amongthe citizens of the United States, and encouragingthe stewardship of these vital areas, is the focus ofthe <strong>National</strong> <strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>System</strong>.The NERR <strong>System</strong>The Coastal Zone <strong>Management</strong> Act and theEstablishment of the <strong>National</strong> <strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Research</strong><strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>System</strong>The <strong>National</strong> <strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>System</strong> was createdby the Coastal Zone <strong>Management</strong> Act (CZMA) of1972, as amended, 16 U.S.C. sec. 1461, to augmentthe Federal Coastal Zone <strong>Management</strong> (CZM)Program. The CZM Program is dedicated to comprehensive,sustainable management of the nation’scoasts.Estuaries also serve as filters: many pollutantsproduced by humans are filtered from the waters asthey pass from upland areas through the plant communitiesof estuaries. This filtering process protectscoastal waters. Estuaries provide important recreationalopportunities, such as swimming, boating,birding, sightseeing, and hiking.Estuaries, however, are easily altered and degradedby human activities. Pollution, sedimentation,and other threats can damage the habitat that somany wildlife populations depend on for survival.The reserve system is a network of protected areasestablished to promote informed management ofthe Nation’s estuaries and coastal habitats. Thereserve system currently consists of 27 reserves in22 states and territories, protecting over 1.3 millionacres of estuarine lands and waters.MissionAs stated in the NERRS regulations, 15 C.F.R.Part 921.1(a), the <strong>National</strong> <strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Research</strong><strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>System</strong> mission is:Figure II.1. Estuaries are rich and dynamic environments where the land, rivers and sea meet.Wells <strong>National</strong> <strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>

The establishment and management, throughFederal-state cooperation, of a national system of<strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>s representative of thevarious regions and estuarine types in the UnitedStates. <strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>s are establishedto provide opportunities for long-term research,education, and interpretation.GoalsFederal regulations, 15 C.F.R. sec. 921.1(b), providefive specific goals for the reserve system:1.2.Ensure a stable environment for researchthrough long-term protection of <strong>National</strong><strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong> resources;Address coastal management issues identifiedas significant through coordinated estuarineresearch within the <strong>System</strong>;3.4.5.Enhance public awareness and understandingof estuarine areas and provide suitable opportunitiesfor public education and interpretation;Promote Federal, state, public and private useof one or more <strong>Reserve</strong>s within the <strong>System</strong>when such entities conduct estuarine research;andConduct and coordinate estuarine researchwithin the <strong>System</strong>, gathering and makingavailable information necessary for improvedunderstanding and management of estuarineareas.<strong>National</strong> <strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>System</strong> StrategicGoals 2003 – 2008The reserve system began a strategic planning processin 1994 in an effort to help NOAA achieveits environmental stewardship mission to “sustainhealthy coasts.” In conjunction with the strategicplanning process, <strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>s Division(ERD) and reserve staff have conducted a multiyearaction planning process on an annual basissince 1996. The resulting three-year action planprovides an overall vision and direction for thereserve system.Figure II.2. Location of the Wells <strong>Reserve</strong>.<strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>System</strong> Strategic <strong>Plan</strong> Mission (revised 2006)To practice and promote coastal and estuarine stewardshipthrough innovative research and education,using a system of protected areas.<strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>System</strong> Strategic <strong>Plan</strong> Goals (revised 2006)1.2.3.Strengthen the protection and managementof representative estuarine ecosystems toadvance estuarine conservation, research andeducation.Increase the use of reserve science and sites toaddress priority coastal management issues.Enhance the public’s ability and willingness tomake informed decisions and take responsibleactions that affect coastal communities andecosystems.Biogeographic RegionsNOAA has identified eleven distinct biogeographicregions and 29 subregions in the U.S., each of whichcontains several types of estuarine ecosystems(15 C.F.R. Part 921, Appendix I and II). Whencomplete, the reserve system will contain examplesof estuarine hydrologic and biological types char-<strong>Management</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>: Introduction

Figure II.3. Biogeographic regions and locations of <strong>National</strong> <strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>s.Acadian1. Northern Gulf of Maine(Eastport to Sheepscot River)2. Southern Gulf of Maine(Sheepscot River to Cape Cod)Virginian3. Southern New England(Cape Cod to Sandy Hook)4. Middle Atlantic(Sandy Hook to Cape Hatteras)5. Chesapeake BayCarolinian6. Northern Carolinas(Cape Hatteras to Santee River)7. South Atlantic(Santee River to St. Johns River)8. East Florida(St. Johns River to Cape Canaveral)West Indian9. Caribbean(Cape Canaveral to Ft. Jefferson and south)10. West Florida(Ft. Jefferson to Cedar Key)Louisianan11. Panhandle Coast(Cedar Key to Mobile Bay)12. Mississippi Delta(Mobile Bay to Galveston)13. Western Gulf(Galveston to Mexican border)Californian14. Southern California(Mexican border to Pt. Conception)15. Central California(Pt. Conception to Cape Mendocino)16. San Francisco BayColumbian17. Middle Pacific(Cape Mendocino to Columbia River)18. Washington Coast(Columbia R. to Vancouver Island)19. Puget SoundGreat Lakes20. Lake Superior, including St. Marys River21. Lakes Michigan and Huron, includingStraits of Mackinac, St. Clair River, and Lake St. Clair22. Lake Erie, includingDetroit River and Niagara Falls23. Lake Ontario, including St. Lawrence RiverFjord24. Southern Alaska(Prince of Wales Island to Cook Inlet)25. Aleutian Islands (Cook Inlet to Bristol Bay)Sub-Arctic26. Northern Alaska(Bristol Bay to Demarcation Point)Insular27. Hawaiian Islands28. Western Pacific Islands29. Eastern Pacific Islands10 Wells <strong>National</strong> <strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>

acteristic of each biogeographic region. As of 2007,the reserve system includes twenty-seven reserves(see Figure II.3).<strong>Reserve</strong> Designation and OperationUnder Federal law (16 U.S.C. sec. 1461), a statecan nominate an estuarine ecosystem for <strong>Research</strong><strong>Reserve</strong> status so long as the site meets the followingconditions:◊◊◊◊The area is representative of its biogeographicregion, is suitable for long-term research andcontributes to the biogeographical and typologicalbalance of the <strong>System</strong>;The law of the coastal State provides long-termprotection for the proposed <strong>Reserve</strong>’s resourcesto ensure a stable environment for research;Designation of the site as a <strong>Reserve</strong> will serveto enhance public awareness and understandingof estuarine areas, and provide suitableopportunities for public education and interpretation;andThe coastal State has complied with therequirements of any regulations issued by theSecretary [of Commerce].<strong>Reserve</strong> boundaries must include an adequate portionof the key land and water areas of the naturalsystem to approximate an ecological unit and toensure effective conservation.If the proposed site is accepted into the reservesystem, it is eligible for NOAA financial assistanceon a cost-share basis with the state. The state exercisesadministrative and management control, consistentwith its obligations to NOAA, as outlinedin a memorandum of understanding. A reserve mayapply to NOAA’s ERD for funds to help supportoperations, research, monitoring, education/interpretation,stewardship, development projects, facilityconstruction, and land acquisition.NERRS Administrative FrameworkThe <strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>s Division (ERD) of theOffice of Ocean and Coastal Resource <strong>Management</strong>(OCRM) administers the reserve system. TheDivision establishes standards for designating andoperating reserves, provides support for reserveoperations and system-wide programming, undertakesprojects that benefit the reserve system, andintegrates information from individual reservesto support decision-making at the national level.As required by Federal regulation, 15 C.F.R. sec.921.40, OCRM periodically evaluates reserves forcompliance with Federal requirements and withthe individual reserve’s Federally-approved managementplan.The ERD currently provides support for threesystem-wide programs: the <strong>System</strong>-WideMonitoring Program, the Graduate <strong>Research</strong>Fellowship Program, and the Coastal TrainingProgram. It also provides support for reserve initiativeson restoration science, invasive species, K-12education, and reserve specific research, monitoring,education and resource stewardship initiativesand programs.<strong>Research</strong> and Monitoring <strong>Plan</strong>[§921.50]The reserve system provides a mechanism foraddressing scientific and technical aspects of coastalmanagement problems through a comprehensive,interdisciplinary, and coordinated approach.<strong>Research</strong> and monitoring programs, including thedevelopment of baseline information, form the basisof this approach. <strong>Reserve</strong> research and monitoringactivities are guided by national plans that identifygoals, priorities, and implementation strategies forthese programs. This approach, when used in combinationwith the education and outreach programs,will help ensure the availability of scientific informationthat has long-term, system-wide consistencyand utility for managers and members of the publicto use in protecting or improving natural processesin their estuaries.<strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>System</strong> <strong>Research</strong> Goals<strong>Research</strong> at the Wells <strong>Reserve</strong> is designed to fulfillthe <strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>System</strong> goals as defined in programregulations. These include:<strong>Management</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>: Introduction11

1.2.3.Address coastal management issues identifiedas significant through coordinated estuarineresearch within the <strong>System</strong>;Promote Federal, state, public and private useof one or more reserves within the <strong>System</strong>when such entities conduct estuarine research;andConduct and coordinate estuarine researchwithin the <strong>System</strong>, gathering and makingavailable information necessary for improvedunderstanding and management of estuarineareas.<strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>System</strong> <strong>Research</strong> Funding PrioritiesFederal regulations, 15 C.F.R. sec. 921.50 (a),specify the purposes for which research funds areto be used:◊◊◊Support management-related research thatwill enhance scientific understanding of the<strong>Reserve</strong> ecosystem,Provide information needed by resource managersand coastal ecosystem policy-makers,andImprove public awareness and understandingof estuarine ecosystems and estuarine managementissues.The reserve system is focusing on the followingresearch areas to support the priorities above:1.Eutrophication, effects of non-point sourcepollution and/or nutrient dynamics;2. Habitat conservation and/or restoration;3.Biodiversity and/or the effects of invasivespecies;with funding for 1-3 years to conduct their research,as well as an opportunity to assist with the researchand monitoring program at a reserve. Projectsmust address coastal management issues identifiedas having regional or national significance; relatethem to the reserve system research focus areas;and be conducted at least partially within one ormore designated reserve sites.Students work with the research coordinator ormanager at the host reserve to develop a plan toparticipate in the reserve’s research and/or monitoringprogram. Students are asked to provide upto 15 hours per week of research and/or monitoringassistance to the reserve; this training may takeplace throughout the school year or may be concentratedduring a specific season.Secondly, research is funded through theCooperative Institute for Coastal and <strong>Estuarine</strong>Environmental Technology (CICEET), a partnershipbetween NOAA and the University of NewHampshire (UNH). CICEET uses the capabilitiesof UNH, the private sector, academic and publicresearch institutions throughout the U.S., as wellas the 26 reserves in the reserve system, to developand apply new environmental technologies andtechniques.<strong>System</strong>-Wide Monitoring ProgramIt is the policy of the Wells <strong>Reserve</strong> to implementeach phase of the <strong>System</strong>-Wide Monitoring <strong>Plan</strong>initiated by ERD in 1989, and as outlined in thereserve system regulations and strategic plan:4.5.Mechanisms for sustaining resources withinestuarine ecosystems; orEconomic, sociological, and/or anthropologicalresearch applicable to estuarine ecosystemmanagement.◊◊Phase I: Environmental Characterization,including studies necessary for inventory andcomprehensive site descriptions;Phase II: Site Profile, to include a synthesis ofdata and information; andThere are two reserve system efforts to fund researchon the previously described areas. The Graduate<strong>Research</strong> Fellowship Program (GRF) supportsstudents to produce high quality research in thereserves. The fellowship provides graduate students◊Phase III: Implementation of the <strong>System</strong>-wideMonitoring Program.The <strong>System</strong>-wide Monitoring Program providesstandardized data on national estuarine environmentaltrends while allowing the flexibility to assess12 Wells <strong>National</strong> <strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>

coastal management issues of regional or localconcern. The principal mission of the monitoringprogram is to develop quantitative measurementsof short-term variability and long-term changesin the integrity and biodiversity of representativeestuarine ecosystems and coastal watersheds forthe purposes of contributing to effective coastalzone management. The program is designed toenhance the value and vision of the reserves as asystem of national references sites. The programcurrently has three main components and the firstis in operation.Abiotic Variables: The monitoring program currentlymeasures pH, conductivity, salinity, temperature,dissolved oxygen, turbidity, and water level.The program also monitors weather, including airtemperature, relative humidity, photosyntheticallyactive radiation, wind speed and direction, barometricpressure and precipitation. In addition, theprogram collects monthly nutrient and chlorophylla samples and monthly diel samples at one SWMPdata logger station. Each reserve uses a set of automatedinstruments and weather stations to collectthese data for submission to a centralized datamanagement office.Biotic Variables: The reserve system will incorporatemonitoring of organisms and habitats into themonitoring program as funds become available.The first aspect likely to be incorporated will quantifyvegetation (e.g., marsh vegetation, submergedaquatic vegetation) patterns and their changeover space and time. Other aspects that could beincorporated include monitoring infaunal benthic,nekton and plankton communities.Land Use, Habitat Mapping and Change: Thiscomponent will be developed to identify changes incoastal ecological conditions with the goal of trackingand evaluating changes in coastal habitats andwatershed land use/cover. The main objective ofthis element will be to examine the links betweenwatershed land use activities and coastal habitatquality.These data are compiled electronically at a centraldata management “hub”, the Centralized Data<strong>Management</strong> Office (CDMO) at the Belle W.Baruch Institute for Marine Biology and Coastal<strong>Research</strong> of the University of South Carolina. Theyprovide additional quality control for data andmetadata and they compile and disseminate the dataand summary statistics via the Web (http://cdmo.baruch.sc.edu) where researchers, coastal managersand educators readily access the information.The metadata meets the standards of the FederalGeographical Data Committee.Education <strong>Plan</strong> [§921.13(a)(4)]The reserve system provides a vehicle to increaseunderstanding and awareness of estuarine systemsand improve decision-making among keyaudiences to promote stewardship of the nation’scoastal resources. Education and interpretation inthe reserves incorporates a range of programs andmethodologies that are systematically tailored tokey audiences around priority coastal resource issuesand incorporate science-based content. <strong>Reserve</strong>staff members work with local communities andregional groups to address coastal resource managementissues, such as non-point source pollution,habitat restoration and invasive species. Throughintegrated research and education programs, thereserves help communities develop strategies todeal successfully with these coastal resource issues.Formal and non-formal education and trainingprograms in the NERRS target K-12 students,teachers, university and college students and faculty,as well as coastal decision-maker audiences suchas environmental groups, professionals involvedin coastal resource management, municipal andcounty zoning boards, planners, elected officials,landscapers, eco-tour operators and professionalassociations.K-12 and professional development programs forteachers include the use of established coastal andestuarine science curricula aligned with state andnational science education standards and frequentlyinvolves both on-site and in-school follow-up activity.<strong>Management</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>: Introduction13

Department of of Commerce<strong>National</strong> Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration<strong>National</strong> Ocean ServiceOffice of of Ocean and Coastal Resource <strong>Management</strong>Coastal Programs DivisionMarine Sanctuaries DivisionFigure II.4. NOAA organizational chart.<strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>s Division<strong>Reserve</strong> education activities are guided by nationalplans that identify goals, priorities, and implementationstrategies for these programs. Education andtraining programs, interpretive exhibits and communityoutreach programs integrate elements ofNERRS science, research and monitoring activitiesand ensure a systematic, multi-faceted, and locallyfocused approach to fostering stewardship.<strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>System</strong> Education Mission and GoalsThe <strong>National</strong> <strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>System</strong>’smission includes an emphasis on education, interpretation,and outreach. Education policy at theWells <strong>Reserve</strong> is designed to fulfill the reservesystem goals as defined in the regulations, 15 C.F.Rsec. 921.1(b). Education goals include:◊◊Enhance public awareness and understandingof estuarine areas and provide suitable opportunitiesfor public education and interpretation;Conduct and coordinate estuarine researchand education within the system, gatheringand making available information necessaryfor improved understanding and managementof estuarine areas.<strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>System</strong> Education ObjectivesEducation-related objectives in the <strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>System</strong>Strategic <strong>Plan</strong> (FY 03-08) include:◊◊Enhance the transfer of knowledge, informationand skills to coastal decision makers forimproved coastal stewardship.Provide education programs for students,teachers and the public to increase literacyabout estuarine systems.<strong>Reserve</strong> <strong>System</strong> Coastal Training ProgramThe Coastal Training Program (CTP) providesup-to-date scientific information and skill-buildingopportunities to coastal decision-makers whoare responsible for making decisions that affectcoastal resources. Through this program, <strong>National</strong><strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>s can ensure that coastaldecision-makers have the knowledge and tools theyneed to address critical resource management issuesof concern to local communities.Coastal Training Programs offered by reservesrelate to coastal habitat conservation and restoration,biodiversity, water quality and sustainable14 Wells <strong>National</strong> <strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>

esource management and integrate reserve-basedresearch, monitoring and stewardship activities.Programs target a range of audiences, such asland-use planners, elected officials, regulators, landdevelopers, community groups, environmentalnon-profits, business and applied scientific groups.These training programs provide opportunities forprofessionals to network across disciplines, anddevelop new collaborative relationships to solvecomplex environmental problems. Additionally,the CTP provides a critical feedback loop to ensurethat decision-makers inform researchers of theirscience-based needs. Programs are developed in avariety of formats ranging from seminars, handsonskill training, participatory workshops, lectures,and technology demonstrations. Participantsbenefit from opportunities to share experiences andnetwork in a multidisciplinary setting, often with a<strong>Reserve</strong>-based field activity.Partnerships are important to the success of theprogram. <strong>Reserve</strong>s work closely with State CoastalPrograms, Sea Grant College extension and educationstaff, and a host of local partners in determiningkey coastal resource issues to address, as well asthe identification of target audiences. Partnershipswith local agencies and organizations are critical inthe exchange and sharing of expertise and resourcesto deliver relevant and accessible training programsthat meet the needs of specific groups.The Coastal Training Program requires a systematicprogram development process, involving periodicreview of the reserve niche in the training providermarket, audience assessments, development of athree to five year program strategy, a marketingplan and the establishment of an advisory group forguidance, program review and perspective in programdevelopment. The Coastal Training Programimplements a performance monitoring system,wherein staff report data in operations progressreports according to a suite of performance indicatorsrelated to increases in participant understanding,applications of learning and enhanced networkingwith peers and experts to inform programs.<strong>Management</strong> <strong>Plan</strong>: Introduction15

16 Wells <strong>National</strong> <strong>Estuarine</strong> <strong>Research</strong> <strong>Reserve</strong>

III. Setting17