Evidence-Based Practice in Foster Parent Training and Support ...

Evidence-Based Practice in Foster Parent Training and Support ...

Evidence-Based Practice in Foster Parent Training and Support ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

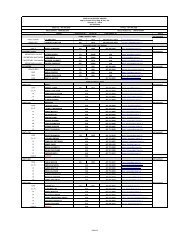

EBP <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>Support</strong>Benefits………………………………………………………………………………………….. 92Integrated Models…………………………………………………………………………….. 96Involvement <strong>in</strong> Program……………………………………………………………………... 97Level of Care………………………………………………………………………………….. 105Respite…………………………………………………………………………………………. 109Social <strong>Support</strong>……………………………………………………………………………….... 109<strong>Support</strong> Inventories………………………………………………………………………...… 112Treatment <strong>Foster</strong> Care………………………………………………………………………. 113Wraparound…………………………………………………………………………………… 114Summary……………………………………………………………………………………….. 117Annotated Bibliography of <strong>Evidence</strong>-<strong>Based</strong> <strong>Practice</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> <strong>Support</strong>………….…. 120References…………………………………………………………………………………… 154APPENDIX I - Quick Reference Guide ...................................................................................166Table A. Outcomes of <strong>Evidence</strong>-<strong>Based</strong> <strong>Practice</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g ................169Table B. Outcomes of <strong>Evidence</strong>-<strong>Based</strong> <strong>Practice</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> <strong>Support</strong>……………..172Center for Advanced Studies <strong>in</strong> Child Welfare (CASCW)University of M<strong>in</strong>nesota School of Social WorkContact: Krist<strong>in</strong>e N. Piescher, Ph.D. kpiesche@umn.edu

EBP <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>Support</strong>Positive <strong>Parent</strong><strong>in</strong>g Program (PPP)Teach<strong>in</strong>g Family Model (TFM)Specialized <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gAttachment <strong>and</strong> BiobehavioralCatch-Up (ABC)Car<strong>in</strong>g for Infants with SubstanceAbuseCommunication & ConflictResolutionEarly Childhood Developmental<strong>and</strong> Nutritional Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gBor, S<strong>and</strong>ers, & Markie-Dadds, 2002; Leung, S<strong>and</strong>ers,Leung, Mak, & Lau, 2003; Mart<strong>in</strong> & S<strong>and</strong>ers, 2003;Roberts, Mazzucchelli, Studman, & S<strong>and</strong>ers, 2006;S<strong>and</strong>ers, Bor, & Morawska, 2007; S<strong>and</strong>ers, Markie-Dadds,Tully, & Bor, 2000; Turner, Richards, & S<strong>and</strong>ers, 2007;Zubrick et al., 2005Bedl<strong>in</strong>gton et al., 1988; Jones & Timbers, 2003; Kirg<strong>in</strong>,Braukman, Atwater, & Wolf,1982; Larzelere et al., 2004;Lee & Thompson, 2008; Lewis, 2005; Slot, Jagers, &Dangel, 1992; Thompson et al., 1996Dozier et al, <strong>in</strong> press; Dozier et al., 2006Burry, 1999Family Resilience Project Schwartz, 2002Prepar<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong>s’ Own Jordan, 1994Children for the <strong>Foster</strong><strong>in</strong>gExperience<strong>Support</strong> <strong>and</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g for Adoptive<strong>and</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> Families (STAFF)Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g Modality<strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> CollegeCobb, Leitenberg, & Burchard, 1982; M<strong>in</strong>nis, Pelosi,Knapp, & Dunn, 2001Gamache, Mirabell, & Avery, 2006Burry & Noble, 2001Buzhardt & Heitzman-Powell, 2006; Pacifici, Delaney,White, Cumm<strong>in</strong>gs, & Nelson, 2005; Pacifici, Delaney,White, Nelson, & Cumm<strong>in</strong>gs, 2006Group vs. Individual Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g Hampson, Schulte & Ricks, 1983On-L<strong>in</strong>e Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gThe evidence base (support<strong>in</strong>g empirical literature) of each tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g model reviewed <strong>in</strong>this report was evaluated us<strong>in</strong>g the California <strong>Evidence</strong>-<strong>Based</strong> Clear<strong>in</strong>ghouse’s (CEBC) Rat<strong>in</strong>gScales (CEBC, 2008e). The evaluation revealed that effective tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g practices currently<strong>in</strong>clude IY, MTFC, PCIT, <strong>and</strong> IY; efficacious tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g practices <strong>in</strong>clude 1-2-3 Magic <strong>and</strong>MTFC-P; promis<strong>in</strong>g tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g practices <strong>in</strong>clude ABC, Car<strong>in</strong>g for Infants with Substance Abuse,Center for Advanced Studies <strong>in</strong> Child Welfare (CASCW)University of M<strong>in</strong>nesota School of Social WorkContact: Krist<strong>in</strong>e N. Piescher, Ph.D. kpiesche@umn.eduiii

EBP <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>Support</strong>communication & Conflict Resolution, FPSTP, KEEP, NPP, PAW, <strong>and</strong> TFM; <strong>and</strong> emerg<strong>in</strong>gtra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g practices <strong>in</strong>clude Behaviorally-Oriented Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, CBT, Early ChildhoodDevelopmental & Nutritional Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, Family Resilience Project, <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> College, MAPP,NOVA, NTU, Prepar<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong>s Own Children for the <strong>Foster</strong><strong>in</strong>g Experience, <strong>and</strong> PRIDE.The review of research suggests that tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g programs are most able to create positivechanges <strong>in</strong> parent<strong>in</strong>g knowledge, attitudes, self-efficacy, behaviors, skills, <strong>and</strong> to a lesser extent,child behaviors. Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g of foster parents is also l<strong>in</strong>ked to foster parent satisfaction, <strong>in</strong>creasedlicens<strong>in</strong>g rates, foster parent retention, placement stability, <strong>and</strong> permanency. (See the QuickReference Guide for associations among these key child welfare outcomes <strong>and</strong> particular fosterparent tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gs <strong>and</strong> support services.)Effective elements of foster parent tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g programs <strong>in</strong>clude: <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g positive parentchild<strong>in</strong>teractions (<strong>in</strong> non-discipl<strong>in</strong>ary situations) <strong>and</strong> emotional communication skills; teach<strong>in</strong>gparents to use time out; <strong>and</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g discipl<strong>in</strong>ary consistency (Kam<strong>in</strong>ski, Valle, Filene, & Boyle,2008). Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g programs that <strong>in</strong>corporate many partners (teachers, foster parents, socialworkers, etc.) with clearly def<strong>in</strong>ed roles appear to be the most promis<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> produc<strong>in</strong>g long termchange (i.e., MTFC, IY). Additionally, tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g that is comprehensive <strong>in</strong> nature <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>corporateseducation on attachment, <strong>and</strong> tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> behavior management methods appears promis<strong>in</strong>g ataddress<strong>in</strong>g the complex tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g needs of treatment foster parents.Although a variety of foster parent tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g programs currently exist, the review ofresearch leads us to believe that more rigorous studies are needed to evaluate the effectiveness ofemerg<strong>in</strong>g practices for both pre-service <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>-service foster parent tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gs. Few of the tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gprograms <strong>in</strong> this report have been evaluated <strong>in</strong> a Treatment <strong>Foster</strong> Care sett<strong>in</strong>g. Although manyCenter for Advanced Studies <strong>in</strong> Child Welfare (CASCW)University of M<strong>in</strong>nesota School of Social WorkContact: Krist<strong>in</strong>e N. Piescher, Ph.D. kpiesche@umn.eduiv

EBP <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>Support</strong>studies have <strong>in</strong>cluded youth who resemble TFC youth <strong>in</strong> their samples, most tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g programshave strictly been evaluated <strong>in</strong> a traditional foster care sett<strong>in</strong>g. Clearly, more work needs to bedone to evaluate these programs for TFC youth.<strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> <strong>Support</strong>The follow<strong>in</strong>g foster parent supports were reviewed <strong>in</strong> this report:ModelBenefitsHealth Insurance & ManagedCareService Provision & ManagedCareStipendsEmpirical LiteratureDavidoff , Hill, Courtot, & Adams, 2008; Jeffrey &Newacheck, 2006; Krauss, Gulley, Sciegaj, & Wells, 2003;Newacheck et al., 2001; Okumura, McPheeters, & Davis,2007; Rosenbach, Lewis, & Qu<strong>in</strong>n, 2000McBeath & Meezan, 2008; Meezan & McBeath, 2008;Campbell & Downs, 1987; Chamberla<strong>in</strong>, Morel<strong>and</strong>, & Reid,1992; Denby & Re<strong>in</strong>dfleisch, 1996; Doyle, 2007; Duncan &Argys, 2007Integrated ModelsKeep<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong>s Tra<strong>in</strong>ed Chamberla<strong>in</strong>, Price, & Laurent et al., 2008; Chamberla<strong>in</strong>,<strong>and</strong> <strong>Support</strong>ed (KEEP)Price & Reid et al., 2008; Price et al, 2008Multidimensional Treatment Chamberla<strong>in</strong>, Leve, & DeGarmo, 2007; Chamberla<strong>in</strong> &<strong>Foster</strong> Care (MTFC)Moore, 1998; Chamberla<strong>in</strong> & Reid, 1998; Eddy, BridgesWhaley, & Chamberla<strong>in</strong>, 2004; Eddy & Chamberla<strong>in</strong>, 2000;Eddy, Whaley & Chamberla<strong>in</strong>, 2004; Harmon, 2005; Kyhle,Hansson, & V<strong>in</strong>nerljung, 2007; Leve & Chamberla<strong>in</strong>, 2005;Leve & Chamberla<strong>in</strong>, 2007; Leve et al., 2005Multidimensional Treatment Fisher, Burraston, & Pears, 2005; Fisher et al., 2000; Fisher<strong>Foster</strong> Care-Preschool (MTFC-P) & Kim, 2007<strong>Support</strong> <strong>and</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g for Bury & Noble, 2001Adoptive <strong>and</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> Families(STAFF)Involvement <strong>in</strong> Program (Collaboration/Partner<strong>in</strong>g)Co-<strong>Parent</strong><strong>in</strong>gL<strong>in</strong>ares, Monalto, & Li et al., 2006; L<strong>in</strong>ares, Monolto, &Rosbruch et al., 2006Ecosystemic Treatment Model Lee & Lynch, 1998Family Reunification Project Simms & Bolden, 1991Center for Advanced Studies <strong>in</strong> Child Welfare (CASCW)University of M<strong>in</strong>nesota School of Social WorkContact: Krist<strong>in</strong>e N. Piescher, Ph.D. kpiesche@umn.eduv

EBP <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>Support</strong><strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Involvement <strong>in</strong>Service Plann<strong>in</strong>gPrivatized Child Welfare Services Friesen, 2001Shared Family <strong>Foster</strong> Care Barth & Price, 1999Shared <strong>Parent</strong><strong>in</strong>g L<strong>and</strong>y & Munro, 1998Level of CarePositive Peer CultureDenby, R<strong>in</strong>dfleisch, & Bean, 1999; Henry, Cossett, Auletta,& Egan, 1991; Rhodes, Orme, & Buehler, 2001; Sanchirico,Jablonka, Lau, & Russell, 1998Leeman, Gibbs & Fuller, 1993; Nas, Brugman, & Koops,2005; Sherer, 1985Re-ED Fields et al., 2006; Hooper et al., 2000; We<strong>in</strong>ste<strong>in</strong>, 1969Stop-Gap McCurdy & McIntyre, 2004RespiteRespite Brown, 1994; Cowen & Reed, 2002; Ptacek et al., 1982Social <strong>Support</strong>Social <strong>Support</strong> Denby, R<strong>in</strong>dfleisch, & Bean, 1999; F<strong>in</strong>n & Kerman, 2004;Fisher et al., 2000; Hansell et al., 1998; Kramer & Houston,1999; Rodger, Cumm<strong>in</strong>gs, & Leschied, 2006; Rhodes et al.,2001; Strozier, Elrod, Beiler, Smith, & Carter, 2004;Urquhart, 1989; Warde & Epste<strong>in</strong>, 2005<strong>Support</strong> InventoriesCasey <strong>Foster</strong> Applicant Inventory Orme et al., 2007Help with <strong>Foster</strong><strong>in</strong>g Inventory Orme, Cherry, & Rhodes, 2006; Orme & Cox et al., 2006Treatment <strong>Foster</strong> CareTreatment <strong>Foster</strong> Care Galaway, Nutter, & Hudson, 1995WraparoundFamily-Centered Intensive CaseManagement (FCICM)<strong>Foster</strong><strong>in</strong>g Individual AssistanceProgram (FIAP)General Wraparound ServicesEvans et al., 1994; Evans, Armstrong, & Kupp<strong>in</strong>ger, 1996Clark & Prange, 1994; Clark, Lee, Prange, & McDonald,1996Bickman et al., 2003; Bruns et al., 2006; Carney & Butell,2003; Crusto et al., 2008; Hyde, Burchard, & Woodworth,1996; Myaard et al., 2000; Pullman et al., 2006In this report, the evidence base of each foster parent support was evaluated us<strong>in</strong>g theCEBC’s Rat<strong>in</strong>g Scales (CEBC, 2008e). Although many areas of support did not <strong>in</strong>clude specificpractice models (e.g., respite, stipends, etc.), each area of support was evaluated <strong>in</strong> light of theexist<strong>in</strong>g empirical literature. This evaluation revealed that effective supports currently <strong>in</strong>cludeCenter for Advanced Studies <strong>in</strong> Child Welfare (CASCW)University of M<strong>in</strong>nesota School of Social WorkContact: Krist<strong>in</strong>e N. Piescher, Ph.D. kpiesche@umn.eduvi

EBP <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>Support</strong>MTFC; efficacious supports <strong>in</strong>clude FCICM, MTFC-P, <strong>and</strong> PPC; promis<strong>in</strong>g supports <strong>in</strong>cludeCo-parent<strong>in</strong>g, FIAP, KEEP, <strong>and</strong> Stop-Gap; <strong>and</strong> emerg<strong>in</strong>g supports <strong>in</strong>clude EcosystemicTreatment Model, Re-ED, Shared Family Care, <strong>and</strong> Shared <strong>Parent</strong><strong>in</strong>g. Specific models of someTFC provider support services have not yet been developed, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g stipends, health <strong>in</strong>surancedelivery, managed care service provision, respite, <strong>and</strong> social support. However, the provision ofthese services to foster parents is associated with improved foster parent <strong>and</strong> child outcomes (seeAppendix I).<strong>Foster</strong> parent’s primary motivation for foster<strong>in</strong>g is to make a positive difference <strong>in</strong>children’s lives (MacGregor, Rodger, Cumm<strong>in</strong>gs, & Leschied, 2006; Rodger, Cumm<strong>in</strong>gs, &Leschied, 2006). However, this cannot be successfully accomplished without a variety ofsupports from agencies, community <strong>and</strong> family members, <strong>and</strong> policymakers. The review ofempirical literature suggests the follow<strong>in</strong>g:BenefitsHealth care benefits for foster children are a major issue for foster parents. This <strong>in</strong>cludesboth the cont<strong>in</strong>uity of coverage <strong>and</strong> coord<strong>in</strong>ation of care for foster children (Kerker & Dore,2006; Leslie, Kelleher, Burns, L<strong>and</strong>sverk, & Rolls, 2003). In addition, the program fund<strong>in</strong>gscheme (fee-for-service versus performance based) has an impact on foster children’s outcomes.Research has shown that children <strong>in</strong> performance-based programs are significantly less likely tobe reunified <strong>and</strong> are more likely to be placed <strong>in</strong> k<strong>in</strong>ship foster homes or adopted (Meezan &McBeath, 2008).Center for Advanced Studies <strong>in</strong> Child Welfare (CASCW)University of M<strong>in</strong>nesota School of Social WorkContact: Krist<strong>in</strong>e N. Piescher, Ph.D. kpiesche@umn.eduvii

EBP <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>Support</strong>As stated earlier, foster parents’ primary motivation for foster<strong>in</strong>g is to help children, notto accumulate monthly funds. The literature suggests that supportive services <strong>and</strong> a monthlystipend can assist foster parents <strong>in</strong> pay<strong>in</strong>g for additional costs associated with car<strong>in</strong>g for childrenwith behavioral issues (such as TFC youth) <strong>and</strong> have a positive impact on foster parent retention(Doyle, 2007; Duncan & Argys, 2007; Meadowcroft & Trout, 1990). However, many fosterparents report that the monthly stipend is <strong>in</strong>adequate to meet the costs associated with car<strong>in</strong>g forfoster children <strong>and</strong> youth (Barbell, 1996; Soliday, 1998), Thus, more research on the costsassociated with car<strong>in</strong>g for TFC youth, <strong>and</strong> the various rates of TFC provider payments is needed.Involvement <strong>in</strong> Service Plann<strong>in</strong>g (Collaboration)<strong>Foster</strong> parents express desire to be <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> the service plann<strong>in</strong>g for children <strong>in</strong> theircare (Brown & Calder, 2002; Denby, R<strong>in</strong>dfleisch, & Bean, 1999; Hudson & Levasseur, 2002;Rhodes, Orme, & Buehler, 2001). Yet, there is a delicate <strong>in</strong>tersection betweenprofessionalization of the foster parent role <strong>and</strong> provid<strong>in</strong>g parental care for foster children, asfoster parents consider themselves parents first <strong>and</strong> foremost (Kirton, 2001). Involvement <strong>in</strong>plann<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> professionalization is l<strong>in</strong>ked to <strong>in</strong>creased foster parent satisfaction <strong>and</strong> retention(Denby, R<strong>in</strong>dfleisch, & Bean, 1999; Rhodes et al., 2001; Sanchirico, Jablonka, Lau, & Russell,1998).Several models of foster parent <strong>in</strong>volvement with biological parents have been developed<strong>and</strong> are <strong>in</strong> the early stages of evaluation (i.e., Co-parent<strong>in</strong>g, Ecosystemic Treatment Model,Shared Family Care, <strong>and</strong> Shared <strong>Parent</strong><strong>in</strong>g). These models require differ<strong>in</strong>g amounts ofcollaboration between biological <strong>and</strong> foster families, rang<strong>in</strong>g from plann<strong>in</strong>g meet<strong>in</strong>gs together toCenter for Advanced Studies <strong>in</strong> Child Welfare (CASCW)University of M<strong>in</strong>nesota School of Social WorkContact: Krist<strong>in</strong>e N. Piescher, Ph.D. kpiesche@umn.eduviii

EBP <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>Support</strong>foster families car<strong>in</strong>g for the entire family rather than just the child. TFC agencies who wish toimplement practices that <strong>in</strong>volve foster parents <strong>in</strong> service plann<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong>/or create opportunities forcollaboration between foster <strong>and</strong> biological parents may f<strong>in</strong>d these programs helpful.Respite CareRespite provides a break for foster parents. The research suggests that respite care is anecessity <strong>and</strong> should be provided by programs (Cowen & Reed, 2002; Rob<strong>in</strong>son, 1995).However, the format for respite will depend on the (chang<strong>in</strong>g) needs of parents (Meadowcroft &Grealish, 1990). Use of respite care is viewed as a deterrent to “burn out” (Meadowcroft &Grealish, 1990) <strong>and</strong> is l<strong>in</strong>ked to decreases <strong>in</strong> stress <strong>and</strong> satisfaction with the process (Cowen &Reed, 2002, Ptacek et al., 1982). It is therefore reasonable to assume that foster care agencies canutilize customer satisfaction surveys to evaluate their respite care services on an ongo<strong>in</strong>g basis asa means of ensur<strong>in</strong>g the provision of the most effective respite services for treatment fosterparents. Additionally, it may be important to survey TFC providers who are not currentlyutiliz<strong>in</strong>g respite services to detect any barriers associated with us<strong>in</strong>g respite care.Social <strong>Support</strong><strong>Support</strong> groups <strong>and</strong> social support can assist foster parents with lifestyle changes <strong>and</strong>adjustments. <strong>Foster</strong> parents stress the importance of ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g connections with other fosterparents, <strong>and</strong> many parents seek assistance from <strong>in</strong>formal sources (such as other foster families,friends, <strong>and</strong> family members) before seek<strong>in</strong>g formal support (Kramer & Houston, 1999). The<strong>in</strong>ternet may be a new area for foster parents to be supported, although current research <strong>in</strong>dicateson-l<strong>in</strong>e sources are <strong>in</strong>frequently used (F<strong>in</strong>n & Kerman, 2004). However, one recent study foundthat an on-l<strong>in</strong>e tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g was effective, <strong>and</strong> could be used with k<strong>in</strong>ship caregivers, to <strong>in</strong>crease self-Center for Advanced Studies <strong>in</strong> Child Welfare (CASCW)University of M<strong>in</strong>nesota School of Social WorkContact: Krist<strong>in</strong>e N. Piescher, Ph.D. kpiesche@umn.eduix

EBP <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>Support</strong>efficacy, teach computer skills, enhance social support, <strong>and</strong> build common ground betweenchildren <strong>and</strong> caregivers (Strozier, Elrod, Beiler, Smith, & Carter, 2004). Social support of fosterparents is l<strong>in</strong>ked to greater foster parent satisfaction <strong>and</strong> resources, as well as improved childbehavior (Denby et al., 1999; Fisher, Gibbs, S<strong>in</strong>clair, & Wilson, 2000).<strong>Support</strong> provided by agencies <strong>and</strong> caseworkers is l<strong>in</strong>ked to greater foster parentsatisfaction <strong>and</strong> retention (Rodger, Cumm<strong>in</strong>gs, & Leschied, 2006; Rhodes et al., 2001; Urquhart,1989). <strong>Support</strong> is also mitigat<strong>in</strong>g factor <strong>in</strong> reduc<strong>in</strong>g stress (Hansell et al., 1998). It is important tonote that k<strong>in</strong>ship <strong>and</strong> non-k<strong>in</strong>ship foster parents have differ<strong>in</strong>g needs, <strong>and</strong> therefore may requiredifferent types or amounts of social support (Cuddeback & Orme, 2002; Oakley, Cuddeback,Buehler, & Orme, 2007).The relationship between the social worker <strong>and</strong> foster family is also key to <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g thesatisfaction <strong>and</strong> retention of foster parents (Denby et al., 1999). <strong>Foster</strong> parents <strong>in</strong>dicate the needfor an open, positive, supportive relationship with the worker (Brown & Calder, 2000; Fisher etal., 2000). <strong>Foster</strong> parents’ satisfaction is related to their perceptions about teamwork,communication, <strong>and</strong> confidence <strong>in</strong> relation to both the child welfare agency <strong>and</strong> its professionals(Rodger et al., 2006).Treatment foster parents may benefit from the development of support models that 1)create additional formal agency supports, <strong>and</strong> 2) help treatment foster parents identify currentsupport needs <strong>and</strong> exp<strong>and</strong> their <strong>in</strong>formal support networks. Additionally, more collaboration <strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>tegration between foster parents <strong>and</strong> agencies is necessary to meet the ever chang<strong>in</strong>g needs offoster parents.Center for Advanced Studies <strong>in</strong> Child Welfare (CASCW)University of M<strong>in</strong>nesota School of Social WorkContact: Krist<strong>in</strong>e N. Piescher, Ph.D. kpiesche@umn.edux

<strong>Evidence</strong>-<strong>Based</strong> <strong>Practice</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>Support</strong>:Implications for Treatment <strong>Foster</strong> Care ProvidersIntroductionThe report on <strong>Evidence</strong>-<strong>Based</strong> <strong>Practice</strong> (EBP) <strong>in</strong> foster parent tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> support is<strong>in</strong>tended to assist <strong>Foster</strong> Family-<strong>Based</strong> Treatment Association (FFTA) foster care agenciesidentify the most effective practices of foster parent tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> support, as determ<strong>in</strong>ed by thestate of current empirical research. This report is based on a comprehensive review of publishedempirical literature conducted by the Center for Advanced Studies <strong>in</strong> Child Welfare (CASCW) atthe University of M<strong>in</strong>nesota’s School of Social Work. The report was developed under theauspices of Federal Title IV-E Fund<strong>in</strong>g, the Center for Advanced Studies <strong>in</strong> Child Welfare, <strong>and</strong>the <strong>Foster</strong> Family-<strong>Based</strong> Treatment Association (FFTA) as part of the Technical Assistance toFFTA Project.The report is organized <strong>in</strong>to two ma<strong>in</strong> sections: 1) <strong>Evidence</strong>-<strong>Based</strong> <strong>Practice</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong><strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g; <strong>and</strong> 2) <strong>Evidence</strong>-<strong>Based</strong> <strong>Practice</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> <strong>Support</strong>. Included <strong>in</strong> eachsection are comprehensive literature reviews <strong>and</strong> annotated bibliographies. The review ofliterature on evidence-based practice <strong>in</strong> foster parent tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g outl<strong>in</strong>es pre-service foster parenttra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g models, parent<strong>in</strong>g programs for foster parents, specialized foster parent tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gs, <strong>and</strong>alternate tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g modalities. The review of literature on evidence-based practices <strong>in</strong> foster parentsupport describes a variety of services that may support foster parents, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g benefits (health<strong>in</strong>surance, service provision, <strong>and</strong> stipends), foster parent collaboration with agency staff <strong>and</strong>biological families, level of care, respite, support from agency workers <strong>and</strong> community members,support <strong>in</strong>ventories, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>tegrated models of support <strong>and</strong> tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. The sections are then1

EBP <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>Support</strong>followed by a bibliographic list of all references used <strong>in</strong> creat<strong>in</strong>g the report. A Quick ReferenceGuide, which provides key f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>and</strong> empirically-based relationships among evidence-basedpractices <strong>in</strong> foster parent tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> support, <strong>and</strong> key child welfare outcomes, accompanies thisreport (see Appendix I).Search MethodologyThe search for empirical research was conducted between May 20, 2008 <strong>and</strong> August 15,2008 us<strong>in</strong>g the follow<strong>in</strong>g databases:University of M<strong>in</strong>nesota Libraries• Child Abuse, Child Welfare, <strong>and</strong> Adoption Database (1965 to December 2007)• Family <strong>and</strong> Society Studies Worldwide Database (1970 to July 2008)• PsychArticles (1988 to July 2008)• Social Sciences Citation Index (1975 to August 2008)• Social Services Abstracts (1980 to July 2008)• Social Work Abstracts (1977 to July 2008) 1World Wide Web• Cochrane Library (1996 to August 15, 2008) athttp://www.mrw.<strong>in</strong>terscience.wiley.com/cochrane• Campell Collaboration at http://www.campbellcollaboration.org• Google Academic1 Includes Medl<strong>in</strong>e 1950 – July 2008; PsycInfo 1856 – July 2008; <strong>and</strong> Social Work Abstracts 1977 – June2008)Center for Advanced Studies <strong>in</strong> Child Welfare (CASCW)University of M<strong>in</strong>nesota School of Social WorkContact: Krist<strong>in</strong>e N. Piescher, Ph.D. kpiesche@umn.edu 2

EBP <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>Support</strong>In conduct<strong>in</strong>g these searches, the keywords “foster parent” <strong>and</strong> “foster care” were <strong>in</strong>dividuallypaired with the follow<strong>in</strong>g:• Tra<strong>in</strong>• <strong>Support</strong>• Respite• <strong>Support</strong> group• Benefit• Profession• Voice• Stipend• Pay• Level of care• Placement disruption• Placement stability• Retention• <strong>Support</strong> system• Involve• Biological parent• Relationship• Collaboration• Reunification• Shared parent<strong>in</strong>g• Inclusive• Insurance• Managed CareThe keywords “multi-dimensional treatment foster care,” “treatment foster care,” <strong>and</strong>“wraparound service” were used to extend the search for empirical literature on foster parenttra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> support. In addition, bibliographies of articles produced by the search methodologyoutl<strong>in</strong>ed above were <strong>in</strong>spected for relevant articles. The Social Science Citation Index was alsoused to locate articles that cited articles produced by the aforementioned search methodology.F<strong>in</strong>ally, all databases were searched us<strong>in</strong>g the name of each model <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> this report askeywords.Center for Advanced Studies <strong>in</strong> Child Welfare (CASCW)University of M<strong>in</strong>nesota School of Social WorkContact: Krist<strong>in</strong>e N. Piescher, Ph.D. kpiesche@umn.edu 3

EBP <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>Support</strong>Term<strong>in</strong>ologyEmpirical ResearchFor this report, the follow<strong>in</strong>g terms were used to describe the empirical research on fosterparent tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> support (<strong>in</strong> order of rigor): r<strong>and</strong>omized controlled trial (RCT), controlledstudy, exploratory study, <strong>and</strong> descriptive study. A r<strong>and</strong>omized controlled trial refers to a study <strong>in</strong>which participants 1) were r<strong>and</strong>omly assigned to experimental <strong>and</strong> control (<strong>and</strong>/or comparativetreatment), <strong>and</strong> 2) completed both pre-tests <strong>and</strong> post-tests. A controlled study is one <strong>in</strong> which theoutcomes of participants from treatment, control, <strong>and</strong>/or comparative treatment groups arecontrasted with one another. These studies utilize a pre-test/post-test design but do not r<strong>and</strong>omlyassign participants to treatment groups. An exploratory study refers to research that utilizes bothpre- <strong>and</strong> post-tests but does not <strong>in</strong>clude a control or comparative treatment group <strong>in</strong> its design.Descriptive studies exam<strong>in</strong>e the outcomes of treatment; however, these studies do not utilizecontrol groups or a pre-test/post-test design. Additionally, some studies <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> this reportwere meta-analyses of empirical research; a meta-analysis is a systematic statistical analysis of aset of exist<strong>in</strong>g evaluations of similar programs <strong>in</strong> order to draw general conclusions, developsupport for hypotheses, <strong>and</strong>/or produce an estimate of overall program effects.<strong>Evidence</strong>-<strong>Based</strong> <strong>Practice</strong>The recent reliance on, <strong>and</strong> dem<strong>and</strong> for, evidence-based practice (EBP) is a relativelynew development <strong>in</strong> child welfare. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to Chaff<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> Friedrich (2004, p. 1097), EBP wascreated due to the recognition that many common health care <strong>and</strong> social services practices arebased more <strong>in</strong> “cl<strong>in</strong>ical lore <strong>and</strong> traditions than on scientific outcome research.” Although thisrepresents a radical view of social work practice, there has been a grow<strong>in</strong>g concern that socialCenter for Advanced Studies <strong>in</strong> Child Welfare (CASCW)University of M<strong>in</strong>nesota School of Social WorkContact: Krist<strong>in</strong>e N. Piescher, Ph.D. kpiesche@umn.edu 4

EBP <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>Support</strong>work practices have been conducted <strong>in</strong> the absence of, or without adequate attention to, evidenceof their effectiveness <strong>in</strong> decision mak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> client care (Gambrill, 2001). Appropriatelyutiliz<strong>in</strong>g EBP <strong>in</strong> child welfare can remedy this by br<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g services more <strong>in</strong> alignment with thebest-available cl<strong>in</strong>ical science, <strong>and</strong> promot<strong>in</strong>g practices which have been demonstrated to be safe<strong>and</strong> effective.An evidence-based practice is def<strong>in</strong>ed as an <strong>in</strong>tervention, program, procedure, or toolwith empirical research to support its efficacy <strong>and</strong>/or effectiveness. Efficacy refers to the capacityof an <strong>in</strong>tervention to produce the desired effect when tested under carefully controlledconditions. These conditions replicate those found <strong>in</strong> a laboratory sett<strong>in</strong>g; the methodologyutilized <strong>in</strong> this research is highly selective <strong>in</strong> terms of the sample, the tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> supervision ofstaff, <strong>and</strong> the implementation of the practice (Chorpita, 2003). These service environments aredue <strong>in</strong> part to needed constra<strong>in</strong>ts imposed by research design, measurement protocols on referralcriteria, <strong>and</strong> concurrent <strong>in</strong>terventions which serve as comparison groups. Effectiveness refers tothe capacity of an <strong>in</strong>tervention to produce the desired effect when utilized <strong>in</strong> a general practicesett<strong>in</strong>g, where the power to control confound<strong>in</strong>g factors is reduced (Nathan & Gorman, 2002).Ideally, effectiveness trials follow efficacy trials <strong>and</strong> are an <strong>in</strong>termediate step between <strong>in</strong>itialefficacy test<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> widespread dissem<strong>in</strong>ation (Chaff<strong>in</strong> & Friedrich, 2004).It is important to th<strong>in</strong>k of EBP as a process of pos<strong>in</strong>g a question, search<strong>in</strong>g for <strong>and</strong>evaluat<strong>in</strong>g the evidence, <strong>and</strong> apply<strong>in</strong>g the evidence with<strong>in</strong> a client- or policy-specific context(Regehr, Stern, & Shlonsky, 2007). EBP blends current best evidence, community values <strong>and</strong>preferences, <strong>and</strong> agency, societal, <strong>and</strong> political considerations <strong>in</strong> order to establish programs <strong>and</strong>policies that are effective <strong>and</strong> contextualized (Gambrill, 2003, 2006; Gray, 2001). In fact, theCenter for Advanced Studies <strong>in</strong> Child Welfare (CASCW)University of M<strong>in</strong>nesota School of Social WorkContact: Krist<strong>in</strong>e N. Piescher, Ph.D. kpiesche@umn.edu 5

EBP <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>Support</strong>most widely cited def<strong>in</strong>ition of EBP emphasizes “the <strong>in</strong>tegration of best research evidence withcl<strong>in</strong>ical expertise <strong>and</strong> patient values” (Sackett, Straus, Richardson, Rosenberg, & Haynes, 2000,p.1). Th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g about EBP as a contextualized process negates the criticism that EBP is acookbook approach that <strong>in</strong>volves extract<strong>in</strong>g best practices from the scientific literature <strong>and</strong>simplistically apply<strong>in</strong>g them to clients without regard to who the clients are, their personalmotivations <strong>and</strong> goals, or other potentially complicat<strong>in</strong>g life situations, or without the expertiseof the social worker <strong>in</strong>volved (Regehr et al., 2007).Regehr et al. (2007) proposed a model of EBP implementation that reflects the multifacetedcontext of social work practice <strong>and</strong> policy (see Figure 1). This model (adapted fromHaynes, Devereaux, & Guyatt, 2002) considers the emerg<strong>in</strong>g research on the ecological<strong>in</strong>fluences that may affect mov<strong>in</strong>g from evidence to practice, such as <strong>in</strong>traorganizational,extraorganizational, <strong>and</strong> practitioner-level factors, as well as the dynamic <strong>and</strong> reciprocal<strong>in</strong>teractions between levels. For EBPs to be effectively implemented, this model suggests thatcl<strong>in</strong>ical expertise <strong>and</strong> judgment are crucial. In practice, professionals must not only evaluate theresearch evidence support<strong>in</strong>g a practice, but they must also draw on their expertise to determ<strong>in</strong>eif a practice is appropriate for a given client <strong>and</strong> context.The purpose of this report is to assist TFC professionals exp<strong>and</strong> their knowledge ofrelevant EBPs <strong>in</strong> foster parent tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> support. This report is <strong>in</strong>tended to help TFCprofessionals become familiar with 1) the variety of EBPs that are currently documented <strong>in</strong> theresearch literature, <strong>and</strong> 2) the evidence base that supports the efficacy <strong>and</strong>/or effectiveness ofthese EBPs. It is important to note that because this report relies solely on practices that haveCenter for Advanced Studies <strong>in</strong> Child Welfare (CASCW)University of M<strong>in</strong>nesota School of Social WorkContact: Krist<strong>in</strong>e N. Piescher, Ph.D. kpiesche@umn.edu 6

EBP <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>Support</strong>been documented <strong>in</strong> the peer-reviewed, published literature, some field practices may not be<strong>in</strong>cluded.Figure 1. Elements of <strong>Evidence</strong>-<strong>Based</strong> Policy <strong>and</strong> <strong>Practice</strong>Political ContextOrganizational M<strong>and</strong>ateSocio/Historical ContextCommunityClientPreferences& ActionsClient & StateCircumstancesProfessionalExpertiseResearch<strong>Evidence</strong>Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g/SupervisionProfessional ContextOrganizational Resources/Constra<strong>in</strong>tsEconomic ContextSOURCE: Regehr, Stern, & Shlonsky (2007)<strong>Evidence</strong>-<strong>Based</strong> <strong>Practice</strong> Rat<strong>in</strong>g ScaleNot all models of foster parent tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> support are equally supported by empiricalresearch, <strong>and</strong> not all empirical research is equally valuable <strong>in</strong> determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g whether or not apractice is considered to be evidence-based. This report utilizes the California <strong>Evidence</strong>-<strong>Based</strong>Clear<strong>in</strong>ghouse for Child Welfare’s Scientific Rat<strong>in</strong>g Scale as a classification system for rat<strong>in</strong>gthe quality of empirical research support<strong>in</strong>g the various models of foster parent tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong>Center for Advanced Studies <strong>in</strong> Child Welfare (CASCW)University of M<strong>in</strong>nesota School of Social WorkContact: Krist<strong>in</strong>e N. Piescher, Ph.D. kpiesche@umn.edu 7

EBP <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>Support</strong>support (CEBC, 2008e). This classification system uses criteria regard<strong>in</strong>g a practice’s cl<strong>in</strong>ical<strong>and</strong>/or empirical support, documentation, acceptance with<strong>in</strong> the field, <strong>and</strong> potential for harm toassign a summary classification score. A lower score <strong>in</strong>dicates a greater level of support for thepractice (see Figure 2). Specific criteria for each classification system category are presented <strong>in</strong>Table 1.Figure 2. California <strong>Evidence</strong>-<strong>Based</strong> Clear<strong>in</strong>ghouse for Child Welfare’s Scientific Rat<strong>in</strong>g ScaleSOURCE: CEBC (2008)Center for Advanced Studies <strong>in</strong> Child Welfare (CASCW)University of M<strong>in</strong>nesota School of Social WorkContact: Krist<strong>in</strong>e N. Piescher, Ph.D. kpiesche@umn.edu 8

Table 1. Criteria for Evaluat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Evidence</strong>-<strong>Based</strong> <strong>Practice</strong>Rat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Evidence</strong>-Base Safety Documentation Research Base Length ofSusta<strong>in</strong>edEffect1 Effective<strong>Practice</strong>2 Efficacious<strong>Practice</strong>3 Promis<strong>in</strong>g<strong>Practice</strong>4 Emerg<strong>in</strong>g<strong>Practice</strong>5 <strong>Evidence</strong> Failsto DemonstrateEffect6 Concern<strong>in</strong>g<strong>Practice</strong>No substantialrisk of harmNo substantialrisk of harmNo substantialrisk of harmOutcomeMeasuresAvailable Multiple Site (RCT) Replication 1 year Reliable<strong>and</strong> ValidAvailable S<strong>in</strong>gle Site (RCT) 6 months Reliable<strong>and</strong> ValidWeight ofResearch<strong>Evidence</strong><strong>Support</strong>spractice’sbenefit<strong>Support</strong>spractice’sbenefitAvailable Controlled Study <strong>Support</strong>spractice’sbenefitAvailable Exploratory or DescriptivestudyAvailable Non-efficacy <strong>in</strong> 2 RCTs Does notsupportpractice’sbenefitAvailableReasonable theoretical, cl<strong>in</strong>ical,empirical, or legal basissuggest<strong>in</strong>g that the practiceconstitutes a risk of harm toclientsSOURCE: adapted from the California <strong>Evidence</strong>-<strong>Based</strong> Clear<strong>in</strong>ghouse for Child Welfare’s Scientific Rat<strong>in</strong>g ScalesNegativeeffect onclients9

EBP <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>Support</strong><strong>Evidence</strong>-<strong>Based</strong> <strong>Practice</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>Support</strong>:Implications for Treatment <strong>Foster</strong> Care ProvidersSection I: <strong>Evidence</strong>-<strong>Based</strong> <strong>Practice</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gReview of LiteratureTreatment foster care (TFC) is a rapidly exp<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g alternative child welfare <strong>and</strong> childmental health service for meet<strong>in</strong>g the needs of children <strong>and</strong> adolescents with serious levels ofemotional, behavioral, <strong>and</strong> medical problems, <strong>and</strong> their families. Treatment foster care programsprovide <strong>in</strong>tensive, foster family-based, <strong>in</strong>dividualized services to children, adolescents, <strong>and</strong> theirfamilies as an alternative to more restrictive residential placement options. Research on TFC<strong>in</strong>dicates that it is less expensive, is able to place more children <strong>in</strong> less restrictive sett<strong>in</strong>gs atdischarge (with <strong>in</strong>creased permanency), <strong>and</strong> produces greater behavioral improvements <strong>in</strong> thechildren served than residential treatments (Hudson, Nutter, & Galaway, 1994; Meadowcroft,Thomlison, & Chamberla<strong>in</strong>, 1994; Reddy & Pfeiffer, 1997).The role of foster parents <strong>in</strong> TFC programs is complex. Much like traditional fosterparents, TFC foster parents are responsible for provid<strong>in</strong>g daily care to children placed <strong>in</strong> theirhomes. However, unlike traditional foster parents (who have little to no responsibility forprovid<strong>in</strong>g treatment to their foster children) TFC foster parents are viewed as the primarytreatment agents. TFC foster parents are responsible for provid<strong>in</strong>g active, structured treatment forfoster children <strong>and</strong> youth with<strong>in</strong> their foster family homes (FFTA, 2008). Because of thissignificant responsibility <strong>and</strong> the high level of emotional, behavioral, <strong>and</strong> medical problems forCenter for Advanced Studies <strong>in</strong> Child Welfare (CASCW)University of M<strong>in</strong>nesota School of Social WorkContact: Krist<strong>in</strong>e N. Piescher, Ph.D. kpiesche@umn.edu 10

EBP <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>Support</strong>children <strong>and</strong> youth <strong>in</strong> their care, TFC foster parents require high levels of tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g tailoredspecifically to the population of children <strong>and</strong> youth <strong>in</strong> their care.Provid<strong>in</strong>g foster care to children with <strong>in</strong>creased emotional, behavioral, <strong>and</strong>/or medicalneeds requires not only extra time, but also greater patience, skill, <strong>and</strong> endurance <strong>in</strong> deal<strong>in</strong>g withthe child's dem<strong>and</strong>s, <strong>and</strong> the effect of the child’s dem<strong>and</strong>s on the foster carers' personal <strong>and</strong>social life (Cliffe, 1991). This may be especially true for foster parents of adolescents (Turner,Macdonald, & Dennis, 2007). However, foster parents often voice that they are unprepared tomeet the dem<strong>and</strong>s of children with <strong>in</strong>creased behavioral <strong>and</strong> emotional needs <strong>and</strong> adolescents <strong>in</strong>their care (Henry, Cossett, Auletta, & Egan, 1991; Rhodes, Orme, & Buehler, 2001; <strong>and</strong>Sanchiricho, Lau, Jablonka, & Russell, 1998). This situation can result <strong>in</strong> placement disruption,which further stra<strong>in</strong>s foster care resources <strong>and</strong> has negative impacts on foster children <strong>and</strong> youth.Placement disruptions <strong>and</strong> frequent changes of foster parents can underm<strong>in</strong>e children's capacityfor develop<strong>in</strong>g mean<strong>in</strong>gful attachments, disrupt friendships, <strong>and</strong> contribute to discont<strong>in</strong>uities <strong>in</strong>education <strong>and</strong> health care (Macdonald, 2004). Additionally, unplanned term<strong>in</strong>ations ofplacements have the potential to dra<strong>in</strong> the field of experienced carers, a much needed but limitedresource, <strong>and</strong> compound the problems of f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g an adequate supply of fosterparents to provide children with stable care (Turner, Macdonald, & Dennis, 2007).This section of the report is <strong>in</strong>tended to assist <strong>Foster</strong> Family-<strong>Based</strong> TreatmentAssociation (FFTA) agencies identify the most successful practices of foster parent tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g byprovid<strong>in</strong>g a comprehensive literature review <strong>and</strong> annotated bibliography of evidence-basedpractices <strong>in</strong> foster parent tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. This section focuses on studies that exam<strong>in</strong>e the effectivenessof <strong>in</strong>terventions <strong>and</strong> models of tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g for foster parents. Both pre-service <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>-service modelsCenter for Advanced Studies <strong>in</strong> Child Welfare (CASCW)University of M<strong>in</strong>nesota School of Social WorkContact: Krist<strong>in</strong>e N. Piescher, Ph.D. kpiesche@umn.edu 11

EBP <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>Support</strong>of tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g are <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the review. The tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g models are divided <strong>in</strong>to four major categories:pre-service foster parent tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gs, parent<strong>in</strong>g models, specialized foster parent tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gs, <strong>and</strong>tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g modalities.Pre-Service Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g ModelsNOVAThe Nova model of foster parent tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g was developed as part of the <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong>Project at Nova University (Pasztor, 1985). The <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Project was based on four ma<strong>in</strong>pr<strong>in</strong>ciples: 1) agency language, recruitment strategies, <strong>and</strong> foster parent support need to change<strong>in</strong> order for foster parents to learn to work <strong>in</strong> ways that are more compatible with permanencyplann<strong>in</strong>g goals, 2) foster parents should be <strong>in</strong>volved as team members <strong>in</strong> permanency plann<strong>in</strong>gagencies, 3) the role of the foster parent should be clearly def<strong>in</strong>ed regard<strong>in</strong>g permanencyplann<strong>in</strong>g responsibilities, <strong>and</strong> 4) foster parent retention depends on the degree to which they aresupported by others <strong>in</strong> the system. The goal of this project was to develop a model of service thatcould be replicated by foster care agencies of all types (i.e., large, small, urban, <strong>and</strong> rural). Themodel has been used <strong>in</strong> 22 states, as well as <strong>in</strong> sections of Ontario, Canada.The tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g component of the Nova model <strong>in</strong>cludes an orientation meet<strong>in</strong>g followed bysix group tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g sessions. These sessions last approximately three hours each <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>clude up to30 participants. The group-based foster parent preservice tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g is comb<strong>in</strong>ed with a home studyprocess. Session content <strong>in</strong>cludes: 1) foster care program goals, <strong>and</strong> agency strengths <strong>and</strong> limits<strong>in</strong> achiev<strong>in</strong>g those goals; 2) foster parent roles <strong>and</strong> responsibilities; <strong>and</strong> 3) the impact of foster<strong>in</strong>gon foster families, <strong>and</strong> on children <strong>and</strong> parents who need foster care services. The tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g usesCenter for Advanced Studies <strong>in</strong> Child Welfare (CASCW)University of M<strong>in</strong>nesota School of Social WorkContact: Krist<strong>in</strong>e N. Piescher, Ph.D. kpiesche@umn.edu 12

EBP <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>Support</strong>learner-centered, nondirective teach<strong>in</strong>g methods to help prospective foster parents assess theirown strengths <strong>and</strong> limits <strong>in</strong> work<strong>in</strong>g with children <strong>and</strong> parents who need foster care services.Role play<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> guided imagery are heavily utilized.The Nova model of tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g is rated as an emerg<strong>in</strong>g practice. The Nova tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g modelhas been associated with <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong> licens<strong>in</strong>g rates <strong>and</strong> placement stability (Pasztor, 1985).Additionally, parents who report this tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g to be useful also report higher satisfaction withfoster parent role dem<strong>and</strong>s (Fees, et al., 1998). This model has not been tested <strong>in</strong> a treatmentfoster care population; however the pr<strong>in</strong>cipals of the <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Project are conducive towork<strong>in</strong>g closely with treatment foster parents.<strong>Parent</strong> Resources for Information, Development, <strong>and</strong> Education (PRIDE)PRIDE was developed by the Child Welfare League of America (CWLA) through acollaboration of 14 state child welfare agencies, two national resource centers, <strong>and</strong> severaluniversities <strong>and</strong> colleges. This model is used by private <strong>and</strong> public child welfare agencies <strong>in</strong> 30states <strong>and</strong> 19 other countries to tra<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> support foster care families. PRIDE is designed tostrengthen the quality of foster care <strong>and</strong> adoption services by provid<strong>in</strong>g a st<strong>and</strong>ardized, structuredprocess for recruit<strong>in</strong>g, tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> select<strong>in</strong>g foster <strong>and</strong> adoptive parents. PRIDE covers topics<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g attachment, plann<strong>in</strong>g for permanency, loss, strengthen<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g familyrelationships, discipl<strong>in</strong>e, <strong>and</strong> general foster care <strong>in</strong>formation.PRIDE is associated with <strong>in</strong>creased foster parent knowledge about work<strong>in</strong>g with fosterchildren <strong>and</strong> youth (Christenson & McMurty, 2007). Though it is widely used <strong>in</strong> pre-servicetra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, PRIDE is rated as an emerg<strong>in</strong>g practice due to the dearth of empirical research tosupport its effectiveness.Center for Advanced Studies <strong>in</strong> Child Welfare (CASCW)University of M<strong>in</strong>nesota School of Social WorkContact: Krist<strong>in</strong>e N. Piescher, Ph.D. kpiesche@umn.edu 13

EBP <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>Support</strong><strong>Parent</strong><strong>in</strong>g Models1-2-3 Magic1-2-3 Magic is a discipl<strong>in</strong>e program for parents of children approximately 2-12 years ofage (Bradley et al., 2003); the program can be used with a variety of children, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g thosewith special needs. Groups of six to 25 participants meet one or two times per week for an hour<strong>and</strong> a half over a duration of four to eight weeks. A homework component is also <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> thetra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. 1-2-3 Magic divides the parent<strong>in</strong>g responsibilities <strong>in</strong>to three straightforward tasks:controll<strong>in</strong>g negative behavior, encourag<strong>in</strong>g good behavior, <strong>and</strong> strengthen<strong>in</strong>g the child-parentrelationship. The program seeks to encourage gentle, but firm, discipl<strong>in</strong>e without argu<strong>in</strong>g,yell<strong>in</strong>g, or spank<strong>in</strong>g.1-2-3 Magic is an efficacious practice <strong>and</strong> is l<strong>in</strong>ked to improved parent<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> childbehaviors (Bradley et al., 2003). This program was designed for parents of children withbehavior problems <strong>in</strong>volv<strong>in</strong>g compliance <strong>and</strong> oppositional issues but was not developed or testedfor children with developmental delays. Most TFC parents would be greatly benefited byparticipat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> this tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g.Behaviorally-Oriented Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gBoyd <strong>and</strong> Remy (1978, 1979) were some of the first researchers to implementbehaviorally-oriented tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g programs for foster parents. Behaviorally-oriented tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gs thatdo not fall under any of the other parent tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g models <strong>in</strong> this report have been implemented asrecently as this year. For example, Van Camp et al. (2008) utilized a behaviorally-orientedtra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g consist<strong>in</strong>g of 30 hours of classroom tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g that was taught <strong>in</strong> weekly three-hoursessions for 10 weeks, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>cluded optional <strong>in</strong>-home visits by a behavioral analyst. ThisCenter for Advanced Studies <strong>in</strong> Child Welfare (CASCW)University of M<strong>in</strong>nesota School of Social WorkContact: Krist<strong>in</strong>e N. Piescher, Ph.D. kpiesche@umn.edu 14

EBP <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>Support</strong>behaviorally-oriented parent<strong>in</strong>g tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g is l<strong>in</strong>ked to <strong>in</strong>creased parent<strong>in</strong>g skills <strong>and</strong> retention offoster parents. However, this type of tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g is rated as an emerg<strong>in</strong>g practice due to theresearchers’ lack of comparison groups <strong>in</strong> the studies. This tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g practice has not been tested<strong>in</strong> a TFC population.Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) – <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g ProgramThe purpose of this group-based tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g is to promote emotional <strong>and</strong> social competence,<strong>and</strong> to prevent, reduce, <strong>and</strong> treat behavioral <strong>and</strong> emotional problems <strong>in</strong> young children (muchlike the Incredible Years model) us<strong>in</strong>g a cognitive-behavioral approach (Macdonald & Turner,2005). The program runs four to five weeks <strong>in</strong> length with sessions last<strong>in</strong>g from three to fivehours each week. The tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g familiarizes carers with an underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g of social learn<strong>in</strong>g theory,<strong>in</strong> terms of both how patterns of behavior develop <strong>and</strong> how behavior can be <strong>in</strong>fluenced us<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>terventions derived from learn<strong>in</strong>g theory. The program places an emphasis on develop<strong>in</strong>g theskills to observe, describe, <strong>and</strong> analyze behavior <strong>in</strong> behavioral terms—the so-called “ABC”analysis. In the program, these skills were developed before mov<strong>in</strong>g on to consider specificstrategies or <strong>in</strong>terventions. However, some fluidity between sessions occurs.The CBT model of foster parent tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g is rated as an emerg<strong>in</strong>g practice. <strong>Parent</strong>s whoparticipate <strong>in</strong> the tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g report satisfaction with the program <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>creased confidence aboutdeal<strong>in</strong>g with difficult behavior, although no significant differences have been found between thetra<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>and</strong> untra<strong>in</strong>ed group on behavior management skills, child behavioral problems, orplacement stability (Macdonald & Turner, 2005). This may prove to be a promis<strong>in</strong>g tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g forTFC parents if the efficacy of this program can be demonstrated <strong>in</strong> the future.Center for Advanced Studies <strong>in</strong> Child Welfare (CASCW)University of M<strong>in</strong>nesota School of Social WorkContact: Krist<strong>in</strong>e N. Piescher, Ph.D. kpiesche@umn.edu 15

EBP <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>Support</strong><strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Skills Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g Program (FPSTP)The <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Skills Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g Program is a foster parent tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g curriculum thatfocuses on develop<strong>in</strong>g help<strong>in</strong>g skills for foster parents of children aged five to 12 (Guerney,1977). The program is given <strong>in</strong> a 10-session group format. N<strong>in</strong>e of the 10 sessions addresshelp<strong>in</strong>g skills, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g skills of empathy, relationship development, underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g child need<strong>and</strong> development, <strong>and</strong> skills of child management. The FPSTP program is l<strong>in</strong>ked to sensitivity tochildren’s needs, effective parent<strong>in</strong>g skills, skills associated with promot<strong>in</strong>g child <strong>and</strong> parentrelationships, <strong>and</strong> attitudes of acceptance towards children (Brown, 1980; Guerney, 1977; <strong>and</strong>Guerney & Wolfgang, 1981). Although FPSTP is rated as a promis<strong>in</strong>g practice, these f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsare based on a traditional foster care population <strong>and</strong> no new studies of FPSTP have beenconducted s<strong>in</strong>ce 1981. The applicability to TFC foster parents may be limited.Incredible Years (IY)The Incredible Years <strong>in</strong>cludes three separate, multifaceted, <strong>and</strong> developmentally-basedcurricula for parents, teachers, <strong>and</strong> children (Webster-Stratton, 2000). IY was designed topromote emotional <strong>and</strong> social competence, <strong>and</strong> to prevent, reduce, <strong>and</strong> treat behavioral <strong>and</strong>emotional problems <strong>in</strong> young children (aged 4-8). The parent, teacher, <strong>and</strong> child programs can beused separately or <strong>in</strong> comb<strong>in</strong>ation. IY <strong>in</strong>cludes treatment versions of the parent <strong>and</strong> childprograms as well as prevention versions for high-risk populations, such as TFC youth.The IY parent<strong>in</strong>g component addresses parental negative affect, negative comm<strong>and</strong>s,poor parent bond<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>effective limit sett<strong>in</strong>g (CEBC, 2008b). <strong>Parent</strong> tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g groups consistof 12-16 participants who meet weekly for two hours. The Basic <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g Program lastsCenter for Advanced Studies <strong>in</strong> Child Welfare (CASCW)University of M<strong>in</strong>nesota School of Social WorkContact: Krist<strong>in</strong>e N. Piescher, Ph.D. kpiesche@umn.edu 16

EBP <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>Support</strong>12-14 weeks. The Advanced <strong>Parent</strong> Program is recommended as a supplemental program for thetreatment version. The entire Basic plus Advance <strong>Parent</strong> Program takes 18-22 weeks tocomplete.The IY child component addresses aggression, conduct problems, social competencyproblems, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, <strong>in</strong>ternaliz<strong>in</strong>g problems such as fears, phobias,<strong>and</strong> somatization (conversion of anxiety <strong>in</strong>to physical symptoms), <strong>and</strong> children experienc<strong>in</strong>gdivorce, ab<strong>and</strong>onment, or abuse (CEBC, 2008b). Children’s groups consist of six participantswho meet weekly for two hours. The Child Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g Program runs 18-22 weeks. The ChildPrevention Program is 20 to 30 weeks <strong>and</strong> may be spaced over two years.IY is rated as an effective practice <strong>and</strong> is l<strong>in</strong>ked to the development <strong>and</strong> ma<strong>in</strong>tenance ofeffective parent<strong>in</strong>g skills <strong>and</strong> improved child behaviors (Baydar, Reid, & Webster-Stratton,2003; Gardner, Burton, & Klimes, 2006; L<strong>in</strong>ares, Montalto, Li, & Oza, 2006; Reid, Webster-Stratton, & Baydar, 2004; Reid, Webster-Stratton & Beaucha<strong>in</strong>e, 2001; <strong>and</strong> Webster-Stratton,2000). IY has not been developed or tested for children with developmental delays. Theapplicability of IY for TFC foster parents is noteworthy.Keep<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>and</strong> K<strong>in</strong> <strong>Parent</strong>s <strong>Support</strong>ed <strong>and</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong>ed (KEEP)Keep<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>and</strong> K<strong>in</strong> <strong>Parent</strong>s <strong>Support</strong>ed <strong>and</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong>ed is program designed to 1) giveparents effective tools for deal<strong>in</strong>g with their child's externaliz<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> other behavioral <strong>and</strong>emotional problems, <strong>and</strong> 2) support parents <strong>in</strong> the implementation of those tools (Price et al.,2008). The foster/k<strong>in</strong> parents' role is framed as that of “key agents of change” with opportunitiesto alter the life course trajectories of the children placed with them. <strong>Foster</strong>/k<strong>in</strong> parents are taughtCenter for Advanced Studies <strong>in</strong> Child Welfare (CASCW)University of M<strong>in</strong>nesota School of Social WorkContact: Krist<strong>in</strong>e N. Piescher, Ph.D. kpiesche@umn.edu 17

EBP <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>Support</strong>methods for encourag<strong>in</strong>g child cooperation, us<strong>in</strong>g behavioral cont<strong>in</strong>gencies <strong>and</strong> effective limitsett<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> balanc<strong>in</strong>g encouragement <strong>and</strong> limits. There are also sessions on deal<strong>in</strong>g with difficultproblem behaviors <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g covert behaviors, promot<strong>in</strong>g school success, encourag<strong>in</strong>g positivepeer relationships, <strong>and</strong> strategies for manag<strong>in</strong>g stress brought on by provid<strong>in</strong>g foster care.Sessions consist of one 90-m<strong>in</strong>ute group meet<strong>in</strong>g per week (plus one 10-m<strong>in</strong>ute telephone callper week) over a course of 16 weeks; 7-10 foster parents are <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> each group. There is anemphasis on active learn<strong>in</strong>g methods, <strong>and</strong> illustrations of primary concepts are presented viarole-plays <strong>and</strong> videotapes.KEEP is rated as a promis<strong>in</strong>g practice <strong>and</strong> is associated with ga<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong> effective parent<strong>in</strong>gskills, improvements <strong>in</strong> child behavior, <strong>and</strong> placement permanency (Chamberla<strong>in</strong>, Price, &Laurent et al., 2008; Chamberla<strong>in</strong>, Price, Reid, & L<strong>and</strong>sverk, 2008; <strong>and</strong> Price et al., 2008).Because of its emphasis on treat<strong>in</strong>g child externaliz<strong>in</strong>g problems, mental health problems, <strong>and</strong>problems <strong>in</strong> school <strong>and</strong> with peer groups, KEEP may be appropriate as a tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g mechanism forTFC foster parents.Model Approach to Partnerships <strong>in</strong> <strong>Parent</strong><strong>in</strong>g (MAPP)The Model Approach to Partnerships <strong>in</strong> <strong>Parent</strong><strong>in</strong>g tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g curriculum is based heavilyupon the NOVA curriculum materials (Lee & Holl<strong>and</strong>, 1991). MAPP stresses develop<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>participants the knowledge, attitudes, <strong>and</strong> skills deemed necessary to serve effectively as fosterparents. The highly-structured MAPP curriculum occurs over a 10-week period with participantgroups. Topics of the curriculum <strong>in</strong>clude the foster care/adoption system, placement of fosterchildren, loss <strong>and</strong> attachment, behavior management, birth family connections, exit<strong>in</strong>g fosterCenter for Advanced Studies <strong>in</strong> Child Welfare (CASCW)University of M<strong>in</strong>nesota School of Social WorkContact: Krist<strong>in</strong>e N. Piescher, Ph.D. kpiesche@umn.edu 18

EBP <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>Support</strong>care, <strong>and</strong> the impacts of foster<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> adopt<strong>in</strong>g on the foster family. All sessions utilize lectures,group discussion <strong>and</strong> shar<strong>in</strong>g, role-play<strong>in</strong>g exercises, <strong>and</strong> guided imagery as learn<strong>in</strong>g techniques.Participants are encouraged to share their own experiences <strong>and</strong> to learn from each other.H<strong>and</strong>outs <strong>and</strong> homework assignments are distributed at each session. The home-studycomponent <strong>in</strong>cludes completion of an extensive family profile, exam<strong>in</strong>ation of family strengths<strong>and</strong> needs, <strong>and</strong> assessment of abilities for foster care.MAPP is rated as an emerg<strong>in</strong>g practice. Although several studies have been conducted totest its effectiveness, none have found MAPP to produce the desired results (Lee & Holl<strong>and</strong>,1991; Puddy & Jackson, 2003; <strong>and</strong> Rhodes, Orme, Cox, & Buehler, 2003). Additionally, familieswith psychosocial problems <strong>and</strong> less resources express greater likelihood of not cont<strong>in</strong>u<strong>in</strong>g fostercare after complet<strong>in</strong>g this pre-service tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g (Rhodes et al., 2003). The benefit of this practiceis questionable for TFC foster parents.Multidimensional Treatment <strong>Foster</strong> Care (MTFC)Multidimensional Treatment <strong>Foster</strong> Care is a model of treatment foster care for children12-18 years old with severe emotional <strong>and</strong> behavioral challenges <strong>and</strong>/or severe del<strong>in</strong>quency(Chamberla<strong>in</strong>, 2003). MTFC aims to create opportunities for youths to successfully live <strong>in</strong>families rather than <strong>in</strong> group or <strong>in</strong>stitutional sett<strong>in</strong>gs, <strong>and</strong> to simultaneously prepare their parents(or other long-term placement) to provide youth with effective parent<strong>in</strong>g (CEBC, 2008c). MTFC<strong>in</strong>cludes four key elements of treatment: 1) provid<strong>in</strong>g youths with a consistent re<strong>in</strong>forc<strong>in</strong>genvironment where he or she is mentored <strong>and</strong> encouraged to develop academic <strong>and</strong> positiveliv<strong>in</strong>g skills, (2) provid<strong>in</strong>g daily structure with clear expectations <strong>and</strong> limits, with well-specifiedCenter for Advanced Studies <strong>in</strong> Child Welfare (CASCW)University of M<strong>in</strong>nesota School of Social WorkContact: Krist<strong>in</strong>e N. Piescher, Ph.D. kpiesche@umn.edu 19

EBP <strong>in</strong> <strong>Foster</strong> <strong>Parent</strong> Tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> <strong>Support</strong>consequences delivered <strong>in</strong> a teach<strong>in</strong>g-oriented manner, (3) provid<strong>in</strong>g close supervision of youths'whereabouts, <strong>and</strong> (4) help<strong>in</strong>g youth to avoid deviant peer associations while provid<strong>in</strong>g them withthe support <strong>and</strong> assistance needed to establish pro-social peer relationships.MTFC is designed to be used for tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g groups of foster parents (less than 10participants per group) over a period of six to n<strong>in</strong>e months (CEBC, 2008c). <strong>Foster</strong> parentstypically are contacted a m<strong>in</strong>imum of seven times per week. These contacts consist of five 10-m<strong>in</strong>ute contacts, one two-hour group contact, <strong>and</strong> additional contacts based on the amount ofsupport or consultation required. For the youth <strong>in</strong> treatment, two contacts per week (consist<strong>in</strong>g ofa weekly <strong>in</strong>dividual one-hour therapy <strong>and</strong> weekly two-hour <strong>in</strong>dividual skills tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g) occur.Biological parents (or other long-term placement resource) experience one contact per week <strong>in</strong>the form of a one-hour family therapy session.MTFC is rated as an effective practice <strong>and</strong> has been associated with less del<strong>in</strong>quency, runaways, violent behavior, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>carceration for TFC youth (Chamberla<strong>in</strong>, Leve, & DeGarmo,2007; Chamberla<strong>in</strong> & Moore, 1998; Chamberla<strong>in</strong> & Reid, 1998; Eddy & Chamberla<strong>in</strong>, 2000;Eddy, Whaley, & Chamberla<strong>in</strong>, 2004, 2004b; Harmon, 2005; Leve & Chamberla<strong>in</strong>, 2005, 2007;<strong>and</strong> Leve, Chamberla<strong>in</strong>, & Reid, 2005). Additionally, components of the MTFC are highly ratedby foster parents (Kyhle, Hansson, & V<strong>in</strong>nerljung, 2007). MTFC is a highly appropriate tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gfor TFC foster parents.Center for Advanced Studies <strong>in</strong> Child Welfare (CASCW)University of M<strong>in</strong>nesota School of Social WorkContact: Krist<strong>in</strong>e N. Piescher, Ph.D. kpiesche@umn.edu 20