america

Swarthmore College Bulletin (September 2006) - ITS

Swarthmore College Bulletin (September 2006) - ITS

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

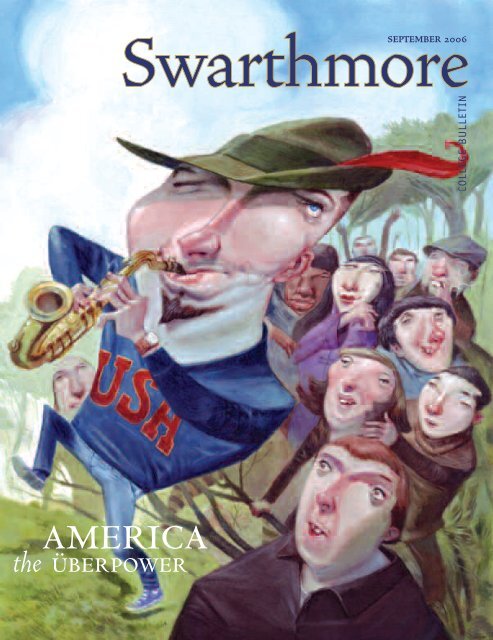

<strong>america</strong>the überpower

features12: America the UbiquitousWhen one nation dominates the world,its power breeds unease, resentment, anddenigration.By Josef Joffe ’6518: Ask the Right QuestionsCharles Bennett ’77 connects the dotsbetween medicine and public policy.By Dana Mackenzie ’7922: Life in HonorsStudents revel in the rigor, challenge,exhilaration—and exhaustion—of today’sHonors Program.By Carol Brévart-Demm30: Painting Chester’s FutureA public mural project seeks to transform astruggling city through collective creativity.By Jeffrey Lottdepartments3: LettersReaders’ voices4: CollectionA miscellany of campus activities34: ConnectionsGroup meetings and faculty travels38: Class NotesAlumni share their lives.47: DeathsRemembering departed friends andclassmates58: Books + ArtsBefore the Separation, an album of songsby Daniel “Freebo” Friedberg ’66Reviewed by Jeffrey Lott70: In My LifeBack to My NatureBy Elisabeth Commanday Swim ’9976: Q + AWhy Is Rafael Zapata So Connected?By Alisa Giardinelliprofiles54: God and GovernmentR. Kent Greenawalt ’58 explores the lawof church and state.By Audree Penner62: Artful Energy 2Robert Storr ’72: curator, artist, teacher,critic, historian, and writerBy Susan Cousins Breen69: Suds and ScienceBiologist Gretchen Margaret Meller ’90helps to create an informal opportunityto share science.By Carol Brévart-DemmON THE COVERMillions of people around the world wear, eat, drink, sing, and danceAmerican—seduced by all things “Made in U.S.A.” Illustration by DaronParton. Story on page 12.OPPOSITEThe Alice Paul Residence Hall glows beneath fireworks celebrating theCollege’s 134th Commencement. Photograph by Ari Levinson.

Swarthmore’sDistinctive Invitationto LeadCOMMENCEMENT ADDRESSBY PRESIDENT ALFRED H. BLOOMhow powerfully they prepare you for leadershipof a truly distinctive kind.Your habit of stepping back to define significantends—and then stepping forward tomake a significant difference—ensures thatyour leadership will be distinguished by yourexceptional abilities for intellectual and ethicalanalysis in setting significant goals andby your resolve to make a difference in energizingmomentum toward those goals.Your habit of seeking to verify what youbelieve and represent to be true ensures thatyour leadership will be anchored in realisticassessment of the obstacles and opportunitiesin its path, open to new information asit unfolds, and vigilant that its own visiondoes not override consequences it does notintend.Your habit of engaging complexityensures that your leadership will take carefulaccount of the complex trade-offs inherentin the choices it makes—trade-offs such asthose between likely benefits and possibleharm, between the competing interests ofdiverse constituencies, between response toindividual circumstances and furthering collectivepurpose. It will be a leadership thatimagines complex solutions that not onlymake the hard decisions required to stay oncourse but at the same time respond as wellas possible to all legitimate claims, not simplythose of highest priority.Your habit of demanding the higheststandards of integrity ensures that yourleadership will, to the best of your awareness,speak the truth; to the extent that prudenceand confidentiality allow, maximizetransparency; and, with unqualified commitment,honor community and public trust.Your habit of valuing others across differencesensures that you, as a leader, will listento others, seek to build common ownershipof the directions you take, weigh carefullythe consequences for fellow human beings inthe trade-offs you make, and be willing todraw the line on decisions that risk visitingunacceptable harm.Your habit of turning away from moralisticand sentimental appeal as well as frominstrumental punishment and reward,ensures that you, as a leader, will empowercolleagues to independently embrace yourvision, rather than conscript followers tothat vision.Across the disciplines, professions,organizations, communities, nations, andthe world you will serve, there exists a deepand pervasive thirst for leadership. And I amconvinced that when humankind has thechoice, it will opt for the very distinctivequalities of leadership you are ready toprovide.So, whenever you envision a promisingdirection for your discipline or profession orspot an imaginative strategy for your forprofitor nonprofit organization, wheneverthe opportunity arises to take responsibilityfor a group, institution, or society, step forwardmindful of the quality and power of theleadership you can deliver. If you don’t,someone else will. And it’s all too likely thatthat “someone” will be less prepared to distinguishsignificant goals and less able toinspire others to embrace them; less resolvedto test the realities that bear on the implementationof those goals; less committed torespond to the full range of complexities atplay in the decisions made; less resolute insustaining integrity; less practiced in openand fair process; less determined to seeksolutions that affirm the value of all humanbeings; less compelled to find and build oncommon ground; and less certain to choosea mode of persuasion which respects colleaguesrather than demeans them.The world is searching for the truly rareand distinctive leadership skills that youhave cultivated here. I know this is so fromobserving the way the world has respondedto the leadership offered by those who, overthe years, have sat in the very seats you occupythis morning. You will know I am rightonce you begin to test your leadership skillsbeyond Swarthmore and watch the worldrespond to you.The credential I will hand you shortly notonly testifies to what you have accomplishedbut promises what you can accomplish in aworld that waits. So I ask you, as you walkfrom those seats to this stage, let go foreverof any hesitancy you might harbor over yourability to lead! TThe foregoing was adapted from PresidentBloom’s address, delivered May 28, 2006.september 2006 :5

By Jeffrey LottPhotographs by Eleftherios KostansSunlight bathed the Scott Amphitheateron one of the first warm days of thespring.Honorary Degree RecipientsNeil Gershenfeld ’81, honorary doctorof science: “[At Swarthmore], I spenthappy hours working in the lab in thebasement of the physics building. At thetime, some schools did laboratory demonstrations.Others would provide lab equipmentalong with instructions on how to doan experiment. At Swarthmore, we weregiven the apparatus and told to fix it. Inretrospect, this is one of the most importantlife lessons I learned. As I went on tomake computerized musical instrumentsand molecular quantum computers andpersonal fabricators, I was driven by thekind of imperative I found at Swarthmore—tosee what could be rather thanwhat is.”Mary Murphy Schroeder ’62, honorarydoctor of laws (right, with Professorof Political Science Carol Nackenoff):“Swarthmore and Professor J. Roland Pennockgave me the encouragement andopportunity to do what few womenthought of doing in 1962—to become alawyer and aspire to public service at thehighest levels…. So my charge to you isabout opportunity. Your generation willfind new heroes. Perhaps some of you willbe among them. Help them, and help eachother reach at least my generation’s goalsof equal justice and equal opportunity, notonly in the United States but throughoutthe world.”Kwame Anthony Appiah, honorarydoctor of humane letters: “Here’s a conundrumfor you: The past century has beenan age of unprecedented scientific andscholarly mastery; it has also been an ageof unprecedented bloodshed.... If we’reso good at math, why haven’t we becomewhizzes at morality? ... When you graduatefrom Swarthmore, you’ll surely add tothe relentless expansion of human knowledge.As you do so, I suggest only, by wayof common sense, that you see what contributionsyou can make to that other,great collective project of moral understanding.”september 2006 :7

collectionELEFTHERIOS KOSTANSA Select Setof StudentsA RECORD 4,850 studentsapplied to the College foradmission to the Class of 2010,a 19 percent increase over2005–2006. Offers of admissionwere sent to 897 (18 percent)of the applicants, fromwhich a class of about 372arrived in late August.Of those admitted fromschools reporting class rank, 33percent are valedictorians orsalutatorians, 56 percent are inthe top 2 percent of their highschool class, and 91 percent arein the top decile. The Class of2010 comes from five continents,36 nations, and 47 U.S.states as well as the District ofColumbia. Sixty-three percentof those admitted were frompublic high schools, 21 percentfrom independent schools, 8percent from schools overseas,and 1 percent were homeschooled.Fifty-two percent ofaccepted students identifiedthemselves as domestic studentsof color: 21 percent asAsian American, 14 percent asAfrican American, 16 percent asLatino/a, and 1 percent asNative American/Hawaiian.According to the 2006Princeton Review survey of“America’s Best Value Colleges,”Swarthmore ranked ninthamong public and private collegesoffering the best educationfor the money.And, for the third year in arow, Swarthmore was ranked3rd among national liberal artscolleges by U.S. News and WorldReport, behind Williams andAmherst colleges. Of theseschools, Swarthmore is the onlyone to have remained in the topthree since the rankings werefirst published in 1983.Tuition, room and board,and other fees will rise to$43,532 in 2006–2007, but theCollege continues to meet alldemonstrated need with scholarships.More than half ofSwarthmore students receivedaid in 2005–2006, with theaverage aid award (scholarships,loans, and campus jobs)totaling $29,500.—Jeffrey LottMembers of the Class of 2010get to know each otherduring orientation in lateAugust.2010No Single Motivationfor TerrorLINKING THE RECENT CONFLICT BETWEEN ISRAEL ANDHEZBOLLAH to the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, the U.S. administrationrepeated the message often used to justify U.S. involvement inIraq: that the “war on terror” presupposes the existence of a singleenemy united around a single cause—religiously motivated hostilityto freedom and the American way of life.Assistant Professor of Political Science Jeffrey Murer disagrees,maintaining that militant Islam is neither unified and cohesive inpurpose nor religious in nature.Co-editor—with Associate Professor of National SecurityAffairs at the Naval War College Derek S. Reveron—and contributorto the book Flashpoints in the War on Terrorism, published inAugust by Routledge, Murer says: “We found that insurgents whoare using Islam around the world are doing so to mark their differencesfrom the states they are opposing. They are primarily fightinglocal wars, asymmetrical wars of independence. Other than that,they have little connection with one another.”8: swarthmore college bulletin

Alumni TravelPrograms toExpandTO INCREASE THE NUMBERand variety of travel optionsoffered to alumni, the College’sAlumni Relations Office recentlyentered into an agreementwith Travel Study Services(TSS), a New York firm that specializesin creating travel packagesfor colleges and universities.“We wanted to offer moretrips and be able to include destinationsthat we haven’t visitedbefore,” says Lisa Lee ’81, directorof alumni relations. “Wealso wanted to have some shortertrips, some that would appealto younger alumni, to peopleinterested in social or environmentalissues—and possiblyeven some opportunities forcommunity service.”Although her office will continueto develop ideas for alumnitravel and work with the facultymembers, Lee says that TSSwill handle the logistics, allowingthe College to offer three ormore trips a year instead of theone or two currently available.For more than 30 years,Swarthmore has offered popularAlumni College Abroad trips toalumni, parents, and friends.Usually accompanied by membersof the faculty, featuredalumni, or guest hosts, participantsin these trips haveenjoyed learning together abouta country or region’s history,economy, religion, art, and culture.Programs include formallectures as well as opportunitiesfor informal discussions duringmeals and tours—and a chancefor Swarthmoreans to get toknow each other while travelingas a group.Trips to three destinationshave been planned for 2007:Russia, China, and river raftingon the Salmon River in Idaho.For more information, see theback cover of this magazine orgo to www.swarthmore.edu/-ac_abroad.xml.—Jeffrey LottAn exhibit titled Beach Series II, 1988-2006, featuring some ofthe most recent work of sculptor Penelope Jencks '58, is ondisplay in the College's List Gallery, Lang Performing ArtsCenter, from Sept. 6 to Oct. 8. Portraying Jencks' childhoodmemories of seeing adults bathing nude during summers onCape Cod, Mass., eight 10-foot-tall, plaster sculptures captureboth the monumentality and physical vulnerability of theirsubjects, as imagined from a child's perspective.COURTESY OF THE LIST GALLERYThe book comprises case studies of 14 conflicts around theworld considered to be part of a “global jihad” by authors from theAir War College, Naval War College, National Defense University,and other colleges and universities including Yale and MIT.Although acknowledging the threat of terrorism, Murer fearsthat American policy exacerbates many conflicts by failing to recognizetheir local quality. “To treat them all the same,” he says, “is todeny the specificity of the solutions that each requires.”Addressing the question of whether terrorism is fueled primarilyby religion or politics, Murer and his co-authors contend that religionis invoked to stir passions and rally followers after leadersmake a political decision to fight.“The ‘war on terror’ is largely based on a flawed understandingof the dynamics that fuel terrorism,” Murer says. “Much of it stemsfrom a failure to recognize that Islam is as varied as Christianity. Noone expects Christianity to be homogeneous. Yet that’s what manypolitical leaders presume about Islam. A change in that misunderstanding—andthe policy changes that would follow—would go along way to undercut terrorist motivations.”—Alisa Giardinelli and Carol Brévart-DemmELEFTHERIOS KOSTANSMurer says that U.S. policymakers should “movebeyond a one-dimensionalworld view that centerson Osama bin Laden andthe tendency to treat theinterface of religion andpolitics as seamless.”september 2006 :9

collectionArboretum HonoredIN APRIL, the Scott Arboretum received renewedaccreditation from the Accreditation Commission of theAmerican Association of Museums. The arboretum was recognizedfor “professional operation and adherence to current and evolvingstandards and best practices; commitment to continual institutionalimprovement; and for public service and accountability through fulfillment of itsmission.” The arboretum celebrated its 75th anniversary with the publication ofa commemorative history. The book is available from the Scott Arboretum ((610)328-8025) or from the College bookstore (www.swarthmore.edu/bookstore).ISTOCKPHOTO.COMGetting to “I Do”PLANNING A WEDDING IS EXCITING—and expensive. Thanks to a new book byAssociate Professor of Psychology AndrewWard and Shirit Kronzon of the University ofPennsylvania’s WhartonSchool, brides-to-be mayhave an easier time “gettingto ‘yes’” (or rather,“I do”) than before. TheBargaining Bride: How toHave the Wedding of YourDreams Without Payingthe Bills of Your Nightmares(New Page Books,2005) offers advice onthe business aspects ofgetting married, discussing the costand compromise involved in choosingthe cake, gown, flowers, music, invitations,photographers as well as dealingwith hidden, unexpected charges likealteration fees, corkage, and cake cutting.Ward, who has conducted research on negotiationfor 15 years, and Kronzon, who teachesit, offer tips on working successfully with familymembers and wedding providers and encouragethe use of a “devil’s advocate” at meetingsand a contingency contract to cover last-minutesurprises.Despite the authors’ meticulous attention tothe business details of weddings, they don’tcover quite everything. “Call us hopelessromantics,” Ward says, “but we don’t discussprenups.”Rhyme and RhythmINTERIOR DESIGNIn a house made all of afterthoughts, wheredusty cupboards block each others’ movesand sockets brood unused while afternoonshold sullen bookshelves in their glare;in a house made all of surfaces, like paperson a desk after colliding at the edge,filth spills through the caulk’s white wedgeto fill in cracks, cement stray hairs.In the heaving jumble’s even grime,things lose their hum of smooth design;and some uncaring understanding madeof a pair of wandering ants intrudesto scatter blindly in the light and losethe way back to the slowly fading fray.THIS POEM WON William Welsh ’08 the Iris N. Spencer UndergraduatePoetry Award from the West Chester University PoetryCenter. Seeking only original, unpublished poems composed intraditional modes of meter, rhyme, and form, the award recognizespoetic achievement among undergraduate poets from DelawareValley colleges and universities. Welsh was the first recipient of theaward, which included a $500 prize and an invitation to the WestChester University Poetry Conference.Welsh says that formal poetry—as opposed to the free versepopular with most contemporary poets—appeals to him because ofits memorability.“Fitting language to certain patterns of rhyme and rhythm givesit a brilliance that is more likely to stick in your mind,” Welsh says.He adds that formal poetry is challenging yet rewarding. “Readinga poem that moves gracefully through a traditional structure is likewatching a dancer with weights tied to his limbs: his performanceis more impressive because he has to overcome externally appliedconstraints. Even better if he can use them to his advantage.”10 : swarthmore college bulletin

WULFF HEINTZ DIES AT 76FORMER DIRECTOR OF THE SPROULOBSERVATORY and Professor Emeritus ofAstronomy Wulff Heintz, age 76, died onJune 10.“Wulff set a model of intense dedicationto advancing scientific knowledge, which,combined with his clarity and enthusiasmfor what he came to know, made learningfrom him irresistible. The community issadly diminished by his passing,” PresidentAlfred H. Bloom said.A native of Würzburg, Germany, Heintzspent World War II in hiding to avoid beingdrafted, after the Nazis made life difficultfor his physician father who disagreed withtheir policies. Although he was still only ateenager, his passion for astronomy—aswell as a subtle sense of humor—wasalready evident. “I used to love the blackoutsduring the bombing runs,” he said,“because they made it so much easier to seethe stars.”In 1953, Heintz received a Ph.D. inastronomy from Munich University, followedby an advanced postdoctoral degreefrom the Technical University of Munich in1967, the same year he came to Swarthmoreas a visiting astronomer. Two years later, hewas appointed an associate professor, servingas department chair from 1972 to 1982.He retired in 1998.During research that spanned more than50 years, Heintz established the foundationfor much of the current knowledge aboutthe structure and evolution of stars and thegalaxies of which they are a part, completingmore than 54,000 double-star measures,discovering 900 new pairs, and calculatingapproximately 500 orbits. He was theauthor of more than 150 research papersand author, co-author, or editor of ninebooks, including Double Stars (1978), whichis arguably the definitive text in his field.Heintz spent his first 26 years at Swarthmorecontinuing to its conclusion an 82-year-old program of photographic observationof the heavens, using the observatory’s24-inch refracting telescope, in place since1912. Concentrating on binary star systems(where two or more stars orbit around eachother) and dwarf stars (those with smallerthan-usualmasses and low luminosities),Heintz completed a collection containingmore than 90,000 photographic plates ofabout 1,500 stars or star systems, includingIn MemoriamWulff Heintz (above) was “a prolificscientist with a great love of observing,”one colleague said. His instrumentwas the 24” refracting telescope inthe College’s Sproul Observatory.their cataloging and evaluation. In anAugust 1994 Bulletin article, he announcedfrom Sproul Observatory, “We havesqueezed out of photography everything wecould do at this location.”Dozens of students contributed toHeintz’s work, staying up all night at the telescope.“It’s difficult for us to be awake forclass the next day after having spent a nightat the telescope,” he told the Bulletin, “butthe observations and their processing continuedon schedule.”After retirement, he continued to use thetelescope in Sproul Observatory, hostingpopular visitor nights to share his passionand knowledge of the origin and propertiesof stars and planets.Heintz’s former colleague Associate Professorof Astronomy Eric Jensen says: “Iremember Wulff as a prolific scientist with agreat love of observing, especially with theSproul telescope. He was always ready toshare his time to educate people about thetelescope and its discoveries, whether it wasthe public visiting during open observatorynights, students learning how to use a telescopefor the first time, or professional colleaguesinquiring about the many observationsmade here by Wulff over the years.”—Carol Brévart-DemmTATIANA MANOOILOFFCOSMAN-WAHL, 1917–2006ON MAY 9, Assistant Professor Emerita ofRussian Tatiana Manooiloff Cosman-Wahl,age 89, died at her home in Riddle Village, aretirement community in Media, Pa.Although born in Siberia,Cosman-Wahl spentmost of her childhoodin China,where her parentshad fled toescape theRussian Revolution.Orphanedat an early age,she was adoptedby social workerIda Pruitt, whoassumed responsibilityfor her education, includinginstruction in Chinese and English,and, in 1938, her immigration to the UnitedStates.Cosman-Wahl served with a China relieforganization in New York City and as a Russiaresearcher at the Library of Congress inWashington, D.C. She obtained a B.A. fromMiddlebury College, an M.A. in Russianfrom Columbia University, and a Ph.D. inRussian literature from New York University.After teaching at several colleges in NewYork City, she served as an assistant professorof Russian at Swarthmore for 10 years,until her retirement in 1982.—Carol Brévart-DemmSTEVEN GOLDBLATT ʼ67HALCYON 1978september 2006 : 11

WHEN ONE NATION DOMINATES THEWORLD, ITS POWER BREEDS UNEASE,RESENTMENT, AND DENIGRATION.By Josef Joffe ’65Illustrations by Daron Parton“America is everywhere” is astatement attributed to the Italian novelistIgnazio Silone (1900–1978). Today, the dictumshould be expanded to include “andeven more so by the day.”When I grew up in postwar West Berlin,before enrolling at Swarthmore, Americawas not everywhere. At that time, Americawas military bases. America was the BerlinAirlift (1948–1949), which saved the Westernhalf of the former Reich capital fromSoviet encirclement; it was the M-48 tanksthat faced down Soviet T-55s across theBerlin Wall in fall 1961. America was Westernsand Grace Kelly movies at the local cinema,interspersed with lots of German, Italian,French, and English films. And it wasjust a single radio station, the AmericanForces Network (AFN), which twice dailyplayed forbidden rock ’n’ roll during programslike Frolic at Five or Bouncing inBavaria on AM radio.The only true American piece of apparelwas a pair of Levi’s. U.S. TV fare wasrationed—mainly because there were onlythree public channels in Germany until themid-1980s, when private networks werelegalized. A phone call to America was soexpensive that it was placed only once ayear, at Christmas or for an important birthday.The Paris editions of The New York Timesand Herald Tribune were read only by Americantourists. In school, it was the occasionalSteinbeck or Hemingway work in translation,and a lot of Goethe, Schiller, andShakespeare. Food was strictly of the localkind: sausages, seasonal vegetables, pork,herring, cabbage, dark bread, potatoes. Sowas drink. When ordered in 1960 at theBerlin Hilton, a Coke consumed 60 percentof a teenager’s weekly allowance. Save forthe tourists and soldiers, America was not areality but a distant myth, as portrayed insoft brushstrokes on TV by series like Lassieand Father Knows Best.No more. Today, the entire world watches,wears, drinks, eats, listens, and dancesAmerican—even in Iran, where it is donein the secrecy of one’s home.Suddenly, Halloween—complete withthe American paraphernalia—has becomean institution in Germany and even inFrance, a country that prides itself for defyingall things American. Suddenly, the GermanWeihnachtsmann looks a lot like theAmerican Santa Claus, and the garishChristmas decorations that festoon middleclassAmerican suburbs in December havesprouted up all over Europe. Thanksgiving,the most American of feasts—completewith turkey and cranberries—is making itsdebut in the more cosmopolitan homes ofGermany. Even the lowly bagel is spreadingacross Europe as an ironic testimony toAmerica’s gastronomic clout. (Originally, thebagel—from the German word beugel,meaning “that which is bent”—was parboiledand baked in the southwest of Germany,whence it emigrated with GermanJews to eastern Europe and then traveledacross the Atlantic to New York’s Lower EastSide.) Pizza, though invented in Naples, haschanged citizenship and swept the world,courtesy of the U.S.-based chains.Not only is American English the world’slingua franca, American culture became theworld’s cultura franca in the last fifth of the20th century. Assemble a few kids from, say,If there is a globalcivilization, it is American.Sweden, Germany, Russia, Argentina, Japan,Israel, and Lebanon in one room. Theywould all be wearing jeans and baseballcaps. How would they communicate? Inmore or less comprehensible English, withan American flavor. And what would theytalk about? About the latest U.S.-madevideo game, American hits on the top-10chart, the TV series South Park, or the mostrecent Hollywood blockbuster. Or theywould debate the relative merits of Windowsand Apple operating systems. No, theywould not talk about Philip Roth or HermanMelville, but neither would they dissectseptember 2006 : 13

Thomas Mann or Dante. The point is thatthey would talk about icons and images“Made in the U.S.A.” If there is a global civilization,it is American—which it was not20 or 30 years ago.Nor is it just a matter of low culture. It isMcDonald’s and Microsoft, Madonna andMoMA, Hollywood and Harvard. If twothirdsof the movie marquees carry anAmerican title in Europe (even in France),the fraction is even greater when it comes totranslated books. The ratio for Germany in2003 was 419 versus 3,732; that is, for everyGerman book translated into English, nineAmerica’s ubiquity goes hand in glovewith seduction. Europe—indeed, most ofthE world—also wants what America has.English-language books were translatedinto German, most of them from America,as a perusal of a German bookstore suggests.A hundred years ago, Berlin’s HumboldtUniversity was the educational modelfor the rest of the world. Tokyo University,Johns Hopkins, Stanford, and the Universityof Chicago were founded in consciousimitation of the German university and itsnovel fusion of teaching and research. Stanford’smotto is taken from the German Renaissancescholar and soldier Ulrich von Hutten(1488–1523): Die Luft der Freiheit weht—the winds of freedom blow.Today, Europe’s universities have losttheir luster, and as they talk reform, theytalk American. Read through mountains ofdebate on university reform, and the twowords you will find most often are “Harvard”and “Stanford.” (Some of us mentionSwarthmore, especially at the new EuropeanCollege of Liberal Arts in Berlin, where I ama trustee.)America’s cultural sway at the beginningof the 21st century surpasses that of Romeor any other empire in history. Rome’s orHabsburg’s cultural penetration of foreignlands stopped exactly at their military borders,and the Soviet Union’s cultural presencein Prague, Budapest, or Warsaw vanishedthe moment the last Russian soldierwas withdrawn. American culture, however,needs no gun to travel. It is everywhere,even in countries where it is denounced asthe “Great Satan.”Joseph Nye, the Harvard political scientist,has coined a term for this phenomenon:“soft power.” Such power does notcome out of the barrel of a gun. It is “lesscoercive and less tangible.” It derives from“attraction” and “ideology.” The distinctionbetween “soft power” and “hard power” isan important one, especially in an age whenbombs and bullets, no matter how “smart,”do not translate easily into politicalpower—that is, the capacity to make othersdo what they otherwise would not do. A perfectexample is America’s swift military victoryagainst Iraq, which was not followed soswiftly by either peace or democracy. Indeed,the relationship between “soft power” andhard influence—that is, America’s ability toget its way in the world—may be nonexistentor, worse, pernicious.Hundreds of millions of people aroundthe world wear, listen, eat, drink, watch, anddance American, but they do not identifythese accoutrements of their daily lives withAmerica. A baseball cap with the Yankeeslogo is the very epitome of things American,but it hardly signifies knowledge of, letalone affection for, the team from New Yorkor America as such. The same is true forAmerican films, foods, or songs. The filmTitanic, released in 1997, has grossed $1.8billion worldwide in box office sales alone.It is still the all-time best seller. With twoexceptions, the next 257 films in the revenueranking are American as well. But this pervasivecultural presence does not seem togenerate “soft power.” There appears to belittle, if any, relationship between artifactand affection.If the relationship is not neutral, it is oneof repellence rather than attraction—andthat is the dark side of the “soft power”coin. The European student movement ofthe late 1960s took its cue from the Berkeleyfree speech movement of 1964. But it quicklyturned anti-American; America wasreviled while it was copied. A telling anecdoteis a march on Frankfurt’s Amerikahausduring the heyday of the German studentmovement. The enraged students wore jeansand American army apparel. They evenplayed a distorted Jimi Hendrix version ofthe American national anthem. But theythrew rocks against the U.S. cultural centernonetheless. Though they wore and listenedAmerican, they targeted precisely theembodiment of America’s cultural presencein Europe.Between Vietnam and Iraq, America’scultural presence has expanded into ubiquity,and so has the resentment of America’s“soft power.”Ubiquity breeds unease, unease breedsresentment, and resentment breeds denigrationas well as visions of American omnipotenceand conspiracy. In some cases, feelingsharden into governmental policy. TheFrench have passed the Toubon law, whichprohibits the use of English words. OtherEuropean nations impose informal quotason American TV fare. America the Ubiquitoushas become America the Excessive.In the affairs of nations, too much hardpower ends up breeding not submission butcounterpower, be it by armament or byalliance. Likewise, great “soft power” doesnot bend hearts but twists minds in resentmentand rage. Yet, how does one balanceagainst “soft power”? No coalition of Europeanuniversities could dethrone Harvardand Stanford. Neither can all the subsidiesfielded by European governments crack thehegemony of Hollywood. To breach the bastionsof American “soft power,” the Europeanswill first have to imitate, then toimprove on, the American model—just asthe Japanese bested the American automotiveindustry after two decades of copycatting—andthe Americans, having dispatchedtheir engineers for study in Britain,overtook the British locomotive industry inthe 19th century. But competition has barelybegun to drive the cultural contest. Instead,14 : swarthmore college bulletin

Europe, mourning the loss of its centuriesoldsupremacy, seeks solace in the defamationof American culture.AMERICA THE BEGUILINGAmerica’s ubiquity goes hand in glove withseduction. Europe—indeed, most of theworld—also wants what America has.Nobody has ever used a gun to driveFrenchmen into one of their 800 McDonald’s.No force need be applied to makeEuropeans buy clothes or watch films“Made in the U.S.A.” Germans take toDenglish as if it were their native tongue.So might the French to Franglais if theirauthorities did not impose fines on suchlinguistic defection. Japan’s cars and electronicshave conquered the world, but veryfew people want to dance like the Japanese.Nor does the rest of the world want to dresslike the Russians or (outside Asia) watchmovies made in “Bollywood,” though Indiaproduces more movies than all Westernnations put together. Nobody risks death onthe high seas to get into China, and thenumber of those who want to go for anM.B.A. in Moscow is still rather small.America’s hard power isbased on its nuclear carrierfleets and its stealthbombers as well as on its$12 trillion dollar economy.But its allure rests on pull,not on push, and it hasdone so since Columbus setout to tap the riches ofIndia but instead ended upin America. Why? One neednot resort to such sonorousterms as “freedom,” the“New Jerusalem,” or JohnWinthrop’s “cittie upon ahill with the eies of all peopleupon them”—conceptsthat evoke religious transcendenceand salvation.America’s magnetism hasmuch more tangible roots.If it is transcendence, itis of a very secular type—asociety where a peddler’sson can still move fromManhattan’s Lower EastSide (now heavily Chinese)to the tranquil suburbs inthe span of one generation. Hence, the bestand the brightest still keep coming, even ifthere is no Metternich, Hitler, or Stalin todrive them out. Nor is citizenshipbequeathed by bloodline. People can becomeAmericans. They do not have to invokeDeutschtum or Italianità to acquire citizenship;they merely have to prove 5 years oflegal residence, swear allegiance, and signon, symbolically speaking, to documents likethe Declaration of Independence and theConstitution. American-ness is credal, notbiological.Two million legal and illegal immigrantspush into the United States each year. Everynew group has contributed its own ingredientto the melting pot (or “salad bowl,” asthe more correct parlance has it). In fact, itwas Russian Jews with (refurbished) nameslike Goldwyn, Mayer, and Warner who firstinterpreted the “American dream” for aworldwide audience on celluloid. It was thedescendants of African slaves who createdan American musical tradition, rangingfrom gospel via jazz to hip-hop, that hasconquered the world. It was a Bavarian Jewby the name of Levi Strauss whose jeansswept the planet. Frenchmen transformedNapa Valley into a household word for wine.Scandinavians implanted a social-democratictradition into the politics of the Midwest,while Irish built the great political machinesof Boston and New York. Hispanics set thearchitectural tone of California and NewMexico.And the “work in progress” continues.According to the article “Alien ScientistsTake Over U.S.A.” (Economist, Aug. 21,1999), at the end of the 20th century, 60percent of the American-based authors ofthe most-cited papers in the physical scienceswere foreign born, as were nearly 30percent of the authors of the most-cited lifescience papers. Almost one-quarter of theleaders of biotech companies that went publicin the early 1990s came from abroad. In aseminar I taught at Stanford in 2004, threeout of five straight-A papers were written bystudents named Zhou, Kim, and SurrajPatel—and the course was not about computerscience, but American foreign policy.And so America has become the first “universalnation.”Demonstration, seduction, imitation—this is the progression that feeds into“America the beguiling.” So why doesn’tirresistible imitation generate affection andsoft power? The answer is simple: Seductioncreates its own repulsion. We hate theseducer for seducing us, and we hate ourselvesfor yielding to temptation. A fineillustration is offered by a cartoon on theJordanian Web site www.mahjoob.com(April 29, 2002, since removed) that transcendsits Arab origins. It shows a Jeep-likeSUV, a pack of cigarettes with a Marlborodesign, a can of Coca-Cola, and a hamburger—allenticing objects of desire, but drippingwith blood. These products “made inthe U.S.A.,” the cartoon insinuates, are theweapons that drive America’s global domination.They are meant to seduce, and yetthey drip with blood that symbolizesheinous imposition. Yield to the seduction,and the price will be the loss of your ownculture, dignity, and power.AMERICA THE ÜBERPOWERAnti-Americanism or any anti-ism flow fromwhat the target is, and not from what itdoes. It is revulsion and contempt thatneeds no evidence, or will find any “proof”that justifies the prejudice. As a generalseptember 2006 : 15

diagnosis, this interpretation is validenough. Hence, visions of omnipotence andconspiracy dancing in the anti-ist’s head aremere figments of an imagination that pinesfor a reprieve from crisis and complexity.The problem with America, though, ismore intricate. Unlike other objects of antiism,America is powerful—indeed, themightiest nation in history. And being easilyleads to doing, or to fears of what Americamight do.As early as 1997, France’s foreign ministerHubert Védrine began to muse about thetemptations of “unilateralism” afflicting theUnited States and about the “risk of hegemony”it posed. Though George W. Bushhad not yet flashed his Texas cowboy bootson the world stage (Bill Clinton was still inthe White House), it was time, according toJim Hoagland in “The New French DiplomaticStyle” (Washington Post, Sept. 25,1997), for Paris to shape “a multipolar worldof the future.” In 1998, France “could notaccept a politically unipolar world or theunilateralism of a single hyperpower,” saidFrench Foreign Minister Hubert Védrine inan interview (Liberation, Nov. 24, 1998). Bythen, the United States was the “indispensablenation,” as Bill Clinton and his secretaryof state Madeleine Albright liked to putit. It was a power that, in 1999, wouldunleash cruise missiles to bludgeon Serbia’sSlobodan Milosevic into the surrender atDayton. By 2002 and 2003, there was sheerhysteria in the streets not only of Europebut of the rest of the world—complete withthe most vicious anti-American epithets like“Nazi” and “global terrorist.”Singular power, especially power liberallyused, transformed a festering resentmentinto an epidemic, and so the anti-Americanobsession that swept the world containedan at least semirational nucleus—the fear ofa giant no longer trammeled by anothersuperpower. No, the United States wouldnot unleash its smart bombs against France,Germany, Brazil, or Malaysia as it haddone—or was about to do—against Milosevicand Hussein. But anti-Americanism, likeother anti-isms, is not about rational expectationsbecause power breeds its own angst.It is the fear of the unknown, of what mighthappen when ropes that once bound thecolossus have fallen away.There had been plenty such safeguards inthe era of bipolarity—when the UnitedStates and the Soviet Union, two superpowers,kept each other in check. Moreover,America had contained itself, so to speak, byharnessing its enormous strength to a hostof international institutions, from theNorth Atlantic Treaty Organization to theUnited Nations. Now, it had become a rawpower, which intimated as of 2002 that itwould go to war against Iraq with or withouta Security Council resolution. Angst ofpower unbound led to the perverse spectacleof millions demonstrating against the UnitedStates and thus, “objectively speaking,”seeking to protect Saddam Hussein, one ofthe most evil tyrants in history.Any anti-ism harbors fantasies about itstarget’s omnipotence; hence the paranoidfrenzy of 2002–2003, which, interestingly,subsided when American weakness in pacifyingIraq was demonstrated in the aftermathof military triumph. It was partschadenfreude, part relief that the giant’s feetof clay were finally being revealed. At anyrate, the fearsome power differentialbetween the United States and the rest ofthe world seemed to have shrunk a bit. Lessclout, less loathing—four words thatexplain hysteria’s decline. Yet, what prescriptionmight follow from this diagnosis?Reducing its might to reduce hatred isnot an option for theworld’s last remainingsuperpower. Nor canAmerica seek to pleasethe world by becomingmore like it—less modernor more postmodern,less capitalist or lessreligious, more parochialand less intrusive. TheUnited States is unalterablyenmeshed in theworld by interest andnecessity, and it will notcease to defend its dominanceagainst all comers.Great powers do notwant to become lesserones, nor can they flattenthemselves as a target.There is no opt-outfor No. 1, unless forcedto do so by a morepotent player, and thereis no change in personafor a nation whoseexceptionalist self-definition is so differentfrom that of the rest of the West.The United States is different from therest, in particular from the postmodernstates of Europe stretching from Italy viaGermany and Austria to the Benelux andScandinavian countries. The EuropeanUnion is fitfully undoing national sovereigntywhile failing to provide its citizenswith a common sense of identity or collectivenationhood. Europe is a matter of practicality,not of pride. As a work in progress,it lacks the underpinning of emotion and“irrational” attachment. Europeans mightbecome all wound up when their nationalsoccer teams win or lose, but the classicalnationalism that drove millions into thetrenches of the 20th century is a fire thatseems to have burned out. If there is a commonidentity, it defines itself in oppositionto the United States—to both its cultureand its clout.As Europe’s strategic dependence on theUnited States has trickled away, new strategicthreats have not emerged. And substrategicthreats like Islamist terrorism are notpotent or pervasive enough to change acreed that proclaims, “Military violencenever solves political problems.” Of course,massive violence did solve Europe’s existen-16 : swarthmore college bulletin

planetary clout, its location athwart twooceans, and its global interests, it remainsthe universal intruder and hence in harm’sway. Its very power is a provocation for thelesser players, and, unlike Europe or Japan,No. 1 cannot huddle under the strategicumbrella of another nation. Nor can it liveby the postmodern ways of Europe, whichfaces no strategic challenge as far as the eyecan see. (Neither would Europe be so postmodernif it had to guarantee its own safety.)The United States is the security lenderof last resort, and there is no InternationalSecurity Fund where the United Statescould apply for a quick emergency loan. AndWith its planetary clout, its locationathwart two oceans, and its globalinterests, the United States’ very power is aprovocation for the world’s lesser players.tial problems twice in the preceding century,but that memory takes second place to thehorrors of those two world wars and toEurope’s refusal to sacrifice a bit of butterfor lots more guns. But why should Europemake that sacrifice? Its actuality is peace,which has made for a far happier way of lifethan did the global ambitions of centuriespast.Europe’s empire is no longer abroad. Itsname is European Union, and it is an“empire by application,” not by imposition.Its allure is a vast market and a social modelgiven to protection, predictability, and theample provision of social goods. Its teleologyis one of transcendence—of borders,strife, and nationalism. Its ethos is pacificityand institutionalized cooperation—theethos of a “civilian power.” Shrinkingsteadily, European armies are no longerrepositories of nationhood (or ladders ofsocial advancement), but organizations withas much prestige as the post office or thebureau of motor vehicles.If this is postmodern, then America ispremodern in its attachment to faith andcommunity, and modern in its identificationwith flag and country. In the postmodernstate, says Robert Cooper in The Breaking ofNations: Order and Chaos in the Twenty-firstCentury (Atlantic Monthly Press, 2003):“The individual has won, and foreign policyis the continuation of domestic concernsbeyond national borders. . . . Individual consumptionreplaces collective glory as thedominant theme of national life [and] war isto be avoided.” The modern state fusedpower to nationhood, and mass mobilizationto a mission. Still, the differencebetween Europe and the United States isnot one of a kind. After all, Americans arejust as consumerist and preoccupied withself and family as are Europeans, nor dothey exactly loathe the culture of entitlementsthat spread throughout the West inthe last half of the 20th century. If the “statist”Europeans invented social security, the“individualist” Americans invented “affirmativeaction” as a set of privileges forgroups defined by color, race, sex, or physicaldisabilities. “Political correctness,” thevery epitome of postmodernism, is an Americaninvention.But if we subtract the postmodern fromthe modern in the United States, a largechunk of the latter remains. For all of itsmultiethnicity, America possesses a keensense of self—and what it should be. Patriotismscores high in any survey, as does religiosity.There is a surfeit of national symbolsthroughout the land, whereas no gasstation in Europe would ever fly an oversizednational flag. With its sense of nationhoodintact, the United States is loath toshare sovereignty and reluctant to submit todictates of international institutions whereit is “one country, one vote.” The UnitedStates still defines itself in terms of a mission,which Europeans no longer do—though the French once invented a missioncivilisatrice for themselves, and the Britishthe “white man’s burden.”The American army still offers newcomersone of the swiftest routes to inclusionand citizenship. And, unlike most of theircounterparts in Europe, the U.S. armedforces are central tools of statecraft. Americanbases are strung around the globe, andno nation has used force more often in thepost–World War II period than has theUnited States—from Korea to Vietnam toIraq and in countless smaller engagementsfrom Central America to Lebanon andSomalia.But whatever the distribution of pre-,post-, and just modern features may be, themost critical difference between Americaand Europe concerns power and position inthe global hierarchy. The United States isthe nation that dwarfs the rest. With itsso, the United States must endure in aHobbesian world where self-reliance is theultimate currency of the realm and goodnessis contingent on safety.But a predominant power that wants tosecure its primacy can choose among variousgrand strategies. While anti-Americanismhas been, and will remain, a fixture ofthe global unconscious, it need not burstinto venomous loathing. Nor is the fear ofAmerican muscle necessarily irrational whenthat power seems to have no bounds.“Oderint, dum metuant”—“Let them hateme as long as they fear me”—the Romanemperor Caligula is supposed to have said.Fear is indeed useful for deterring others,but it may turn into a vexing liability whengreat power must achieve great ends in aworld that cannot defeat, but can defy,America. TJosef Joffe is publisher-editor of the Germannewspaper Die Zeit and a fellow at StanfordUniversity’s Hoover Institute. This essay isadapted from his new book Überpower: TheImperial Temptation of America by Josef Joffe(W.W. Norton & Co., Inc., 2006, with permission).Daron Parton is an English artist andillustrator who lives and works in New Zealand.september 2006 : 17

Charles Bennett has hired 21 Swarthmore students or young alumni to work in hisNorthwestern University lab since 1998. The amount of responsibility he gives themis unusual—there are no make-work tasks. Project coordinators (left to right)Neal Dandade ’06, Cara Angelotta ’05, Charlie Buffie ’06, and Cara Tigue ’06 areseen here with Bennett at the V.A. Lakeside Hospital in Chicago.LLOYD DEGRANE18 : swarthmore college bulletin

A s k t h e{ R i g h t }Q u e s t i o n sCHARLES BENNETT ’77 CONNECTS THE DOTSBETWEEN MEDICINE AND PUBLIC POLICY.By Dana Mackenzie ’79At Swarthmore, Charles Bennett had several heroes.One was the late Franklin and Betty Barr Professor of EconomicsBernard Saffran—a hero to many students. “I had him as a microeconomicsteacher in an honors seminar,” Bennett says. “Bernie wasalways about being careful with your thinking. He pushed me tothink about the creative aspects of what you are doing.” A secondidol was a fellow mathematics major, Dave Bayer ’77 (see “BeautifulMath,” June 2002 Bulletin), who exemplified for Bennett what creativethinking meant.“What I learned during my years at Swarthmore was that the creativepeople were the ones who could ask the right questions,” Bennettsays. He was good at answering questions—good enough tograduate with high honors. At the time, though, he found it frustratingthat he could not figure out the right questions to ask, the wayBayer could.But something must have rubbed off on Bennett, now a professorof medicine in the division of hematology and oncology atNorthwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine. There, hehas founded one of the country’s foremost centers for investigatingadverse drug reactions. The center’s success is based on asking theright questions about drug safety. Why did this patient get seriouslyill after taking drug X? How many similar cases have been reported?How many cases have not been reported because no one noticed theconnection? And how can we track them down?In 2001, Bennett received funding from the National Institutesof Health to develop the academic watchdog group RADAR. Theacronym stands for Research on Adverse Drug Events and Reports(with some poetic license). RADAR now has eight full-time staffmembers and about 45 collaborators. Although the Food and DrugAdministration (FDA) is charged with oversight of the nation’spharmaceuticals, Bennett insists that the two are not in competition.“We’re not going to be better [than the FDA], but we can becomplementary,” he says. The FDA’s drug safety program could becompared to a huge network of weather sensors; every year, itreceives 250,000 adverse event reports associated with thousandsof different medications. In contrast, RADAR doesn’t evaluate everygust of wind—it looks for big storms. Bennett’s group investigatesprimarily cancer drugs, with side effects that have been either fatalor required major medical intervention. The drugs they investigateare market leaders, usually with hundreds of millions of dollars insales. So far they have found 16 drugs that fit this profile.As so often happens in science, Bennett got interested in adversedrug reactions because of a personal experience. “My father’s bestfriend was admitted to Northwestern with a very rare disease calledthrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura [TTP],” he says. Discoveredin 1924, TTP is named for the purplish spots (purpura) that appearon the skin of its victims, due to ruptured blood vessels. If leftuntreated, it kills 90 percent of its victims within days. It was notuntil 1992 that a lifesaving treatment was identified. With thistreatment, emergency filtering of the patient’s blood, the mortalityrate for TTP is now 10 percent. But fortunately, TTP is rare, affectingroughly one person in a million.Bennett’s family friend survived, but he couldn’t stop wonderingwhy she had come up on the wrong end of that one-in-a-million lottery.As a hematologist/oncologist, he knew the right people to ask.“I told other doctors her story, and several said they had hadpatients with the same diagnosis,” he says. “They had all taken thesame drug 2 weeks before they got sick.” It was a drug called Ticlid,an anti-clotting medication for people at risk of strokes or heartattacks. Within 3 months, Bennett had obtained information on 60patients with TTP associated with Ticlid, 20 of whom had died. Forpatients on Ticlid, he estimated that the odds of getting TTP wereabout one in 1,600. It was uncommon enough that it had not beenreported previously—but far too common for comfort.Bennett’s report, published in 1998, caused an earthquake in thelucrative market of heart-attack medications. Roche, the companythat makes Ticlid, was forced by the FDA to write a “Dear Doctor”letter to physicians, describing the risk of TTP. The bottom droppedout of the market for Ticlid, which was replaced by a competitor’sdrug, Plavix—now the second-leading drug in the world in dollarsales. (Ironically, in 2000, Bennett reported in the New EnglandJournal of Medicine that Plavix caused TTP as well—just not as frequently.The manufacturers of Plavix also sent a “Dear Doctor” letterto physicians.)september 2006 : 19

“The data on Ticlid had beensitting in several locations, butno one had taken the time tosynthesize it,” Bennett says.“That made me think,how many other drug sideeffects are out there thatpeople don’t know about?”He set out to find the answer.For Bennett, the TTP story was life changing. “I realized that thedata on Ticlid had been sitting in several locations, but no one hadtaken time to synthesize it. That made me think, how many otherdrug side effects are out there that people don’t know about? Moreimportant, how many cancer patients die from side effects of drugs,and the family and the doctor mistakenly attribute the death to thecancer?” Thus, the idea for RADAR was born.One of RADAR’s other high-profile cases concerned a drugcalled epoetin, which is prescribed to prevent anemia in cancerpatients and patients with kidney failure. For 10 years after it firstbecame available, there were no problems with it, but, in 1998,something went drastically wrong. “All of a sudden, 11 patients onepoetin in Paris became horribly anemic, so badly that they weregetting transfusions every other day,” Bennett says.“When I first read about the 11 cases, I was sure that there mustbe more,” Bennett says. “We requested all the data we could fromthe FDA. The data existed, but it took 9 months to clean up thedatabase. There were three epoetin formulations that were soldworldwide (although only one is available in the United States),and we had to identify which one the affected patients had beentaking. Sometimes they would be switching formulations right andleft. It took a fair bit of detective work to realize that it was onecompany’s product that was causing the problem.” They eventuallyidentified 200 cases of the severe anemia, concentrated in fourcountries—England, France, Canada, and Australia.The problematic formulation was called Eprex, manufactured byJohnson & Johnson (but sold only outside the United States). As itturned out, 1998 was the year that mad-cow disease became amajor concern in England. Regulatory authorities in Europebelieved that a stabilizing ingredient in Eprex, called human serumalbumin, could transmit mad-cow disease. To be safe, they requiredthe company to change its manufacturing process. Unfortunately,the revised formulation caused an immune reaction in somepatients. But why only in those four countries? It turned out thatthey were the ones whose health services required doctors to injectEprex into the skin, to save money. “We showed that if theystopped administering Eprex subcutaneously; if they bit the financialbullet and injected it intravenously, the side effect would goaway,” Bennett says. (Intravenous injections require higher dosagesbecause the drug is more quickly flushed from the body.) Indeed,since 2004, when Bennett published his findings, the frequency ofthis side effect has dropped to near zero. “We saved a $14 billionmarket and preserved the quality of life for hundreds of thousandsof patients with kidney failure,” says Bennett.It may seem odd to hear a doctor talking about saving markets,but Bennett has an unusual background. He is one of a handful ofmedical doctors who also has a Ph.D. in public policy. HenryKissinger handed him his doctoral diploma from the RAND GraduateSchool in Santa Monica in 1991.“In the world of oncology, I was the first physician to earn aPh.D. in public policy,” he says. It was not an easy decision to goback to the life of a graduate student after a decade of training inmedicine. Yet the sacrifice has paid dividends. His public-policybackground has enabled Bennett to co-author papers with a NobelPrize winner (Barry Blumberg, discoverer of the hepatitis B virus)and also with his Swarthmore mentor Bernie Saffran.The interface between medicine and public policy is huge. Adversedrug reactions are only a part of Bennett’s work. He has also studiedthe link between low literacy and cancer. For example, doctorshave known for years that black men with prostate cancer tend tohave more advanced cases when they are first diagnosed. Bennettshowed that the difference has nothing to do with biology. Maleswith poor literacy skills are not informed about the need forprostate cancer screening, whether they are black or white. The policyimplication is clear: All men need to be informed about cancerscreening in a way that they can understand. Brochures thatassume a high school reading level will not work.So Bennett turned to another medium. “We hired veterans to beactors in a video that informs veterans about cancer screening,” hesays. “They sit in the cafeteria, discussing cancer screening atlunch. At the end of the video, it says that so-and-so served in20 : swarthmore college bulletin

Korea, this guy served in Vietnam, that guy was at Normandy. It’ssomething the patients at the veterans’ hospital can really relate to.We showed that we could markedly increase the rate of screening,at a cost of only $100 per person. It’s unbelievably cost-effective.”Recently, Bennett and Northwestern received $3.2 million fromthe National Cancer Institute to participate in a multicenter studycalled the Patient Navigator Program, which will help inner-cityChicago residents who are at high risk for cancer to navigate theVeterans Administration and county health care systems. Bennettsees it as a counterpoint to his work on adverse drug reactions:“RADAR is cutting-edge in terms of science, and Navigator is cutting-edgein terms of service.”In recent years, Bennett’s work has brought him back in touchwith Swarthmore. In 1999, he co-wrote a paper that appeared asthe lead article in the Journal of the American Medical Association.Bernie Saffran was a co-author. Because the subject was sensitive—it showed that drug companies were letting bias interfere with theireconomic evaluation of new products—Saffran’s participation as aneutral economist was crucial. “His was a voice of reason,” Bennettsays. “Bernie told me not to overemphasize the findings but to bevery precise and stay on point.” Several years later, at Saffran’smemorial service, Bennett found out that his former professor hadbeen very proud of that paper.Another co-author on the same paper with Saffran was MarkFriedberg ’98, who, Bennett says, did excellent work on the projectand presented it at a national meeting. Since then, Bennett hasmade a regular habit of employing Swarthmore students as internsand research assistants. He has hired 21 Swarthmore students overall,including three interns and three 2006 graduates this yearalone. “Charlie has been a great mentor,” says Cara Angelotta ’05,who is a project coordinator for RADAR. “It has been great to workfor him because, in a way, I feel as if I am still at Swarthmore. I’mconstantly learning and being presented with challenges, but in avery supportive environment.” Angelotta will work with RADAR foranother year and then go to medical school.The amount of responsibility that Bennett gives to undergraduateswho work for him is unusual—no make-work tasks. Nearlyhalf the papers he has written at Northwestern since Friedbergworked there have had a Swarthmore student as co-author. Theyeven help him write grant proposals, which are the lifeblood of anyacademic researcher.“My colleagues are amazed that I allow [undergraduates] tohave major roles in the grant preparation efforts,” Bennett says. Buthe believes Swarthmore students are exceptional because of theirwriting skills and motivation to improve the world.Bennett’s track record seems to justify the faith he puts in thestudents. He currently has 10 active grants totaling $10 million.The students also benefit from the experience. “They have beenimportant co-authors on papers that appear in journals that are outof reach even for many senior academic researchers,” Bennett says.“That’s why, when they apply to medical school, several of themhave received full scholarships to top-tier medical schools such asHarvard, Stanford, Emory, the University of Michigan, and Penn.”Bennett’s own status also continues to rise. This fall, he willreceive an endowed chair at Kellogg, the Northwestern UniversityBusiness School, concurrent with his professorship in the medicalschool. The new professorship will connect the lines between hispublic policy and medical research efforts. Bennett; his wife, Amy;and their 7-year-old son, Andrew, are firmly entrenched in Chicago—atleast, they hope, until Andrew matriculates to Swarthmorefor the Class of 2021.Meanwhile, he hopes that he can continue to keep RADARfunded. It’s an uphill battle, because federal funding opportunitieshave dropped by half since the Iraq War began. “We really hopesome white knight comes out of the blue and understands that weare trying to battle companies that have billions of dollars on thetable, while saving thousands of lives,” Bennett says. However, ashe said in a recent television interview, “If I save just one life, I feelgood.” TDana Mackenzie ’79 is a freelance science writer and author of The BigSplat, or How Our Moon Came to Be.september 2006 : 21

IT’S RIGOROUS, DEMANDING,CHALLENGING, EXHAUSTING,EXHILARATING—ANDTHAT’SWHATSTUDENTS LOVE ABOUTSWARTHMORE’SHONORSPROGRAM.By Carol Brévart-DemmPhotographs by Eleftherios Kostans22 : swarthmore college bulletin

Fiedler, however, plans to become aneconomist, not a mathematician. “My InternationalEconomics seminar with Professor[Stephen] Golub was awesome,” he says.“He struck a great balance between textbookwork and articles he brought in to supplementthem. Students made presentations,building the theory bit by bit, and he’s sogood at asking the next question and bitingoff the right chunk for that certain studentto do. He enabled us to work together reallyeffectively.”The rigors of the Honors Program do notprevent Fiedler from engaging in extracurricularactivities. He is the scheduling coordinatorand a writing associate in the WritingAssociates Program, an advisory boardmember and mentor in the Student AcademicMentor Program, a teaching assistantand tutor in the Economics Department aswell as a member of the a cappella groupSticks and Stones and technical consultantfor the College Young Democrats’ Web sitewww.garnetdonkey.com.“Honors was a good fit for me,” Rhiannon Graybill says. “I like being able to focusintensively on something, and I like the way the honors seminars are dialogic.”While Fiedler talks math, Rhiannon Graybill’06, an honors religion major and honorsinterpretation theory minor, sits in the sciencecenter’s Eldridge Commons, her eyesriveted to her laptop screen as she writes theconclusion to her honors thesis.“I’m writing about the Tower of Babel,analyzing the biblical story as a story in theBible and as a story that teaches us how toread the Bible,” she explains. Graybill arguesthat the Tower of Babel presents an alternativeto what she calls the Sinaitic model ofunderstanding language, law, and interpretation.Her adviser, Associate Professor ofReligion Nathaniel Deutsch says: “Rhiannoncame up with a thought-provoking andoriginal hypothesis and followed it through.She has uncovered and explored somethings that nobody—including contemporarybiblical scholars—has actually evertouched on.”In addition to three other honors preparations,Graybill, who received a SwarthmoreFoundation grant in 2004 and thePhilip M. Hicks Prize for Literary CriticismEssay and a Mellon Mays UndergraduateFellowship in 2005, has learned Hebrew sothat she can read the Hebrew Bible and theMidrash in their original language. Aftervisiting Morocco last year, she also began tostudy Arabic. Outside class, she is a cofounderof the TOPSoccer organization—avolunteer group that enables physicallychallenged children to play soccer—and hasserved as a resident assistant.IN THE FREAR ENSEMBLE THEATRE, the LangPerforming Arts Center’s “black box,” NealDandade ’06, an honors theater major andhonors English literature minor who is alsoa premed student, rehearses Edward Albee’sZoo Story, one of three theater preparations.24 : swarthmore college bulletin

Albee’s 1958 play explores isolation andclass differences through the story of Jerry,a poor man consumed with loneliness, whobegins a conversation with Peter, a wealthyman, and ultimately forces Peter to help himcommit suicide. Dandade is collaboratingwith visiting director Ross Manson, founderof the Toronto-based Volcano TheaterCompany.Dandade, whose parents left India in the1970s to move to El Paso, Texas, is playingJerry, the main character. Along with the twoprotagonists’ socioeconomic differences,Dandade introduces a racial element intothe play. He makes Jerry’s character PalestinianAmerican to place the piece in apost–Sept. 11 context.As they rehearse, Dandade,extremely self-critical,pauses several times tocorrect flaws in his acting.Donning a scruffy, oversizedovercoat, he becomes Jerry,rendering masterfully thedejected slouch of the downtrodden.His expressive face isable to mold itself easily to portrayboth the anguish of a deeplyunhappy man and his animatedstruggle to hold Peter’s attention ashe tells stories of the rooming housewhere he lives. He has perfected anArabic accent.“You’re hitting all the beats, gettingall the details,” Manson tells him.“This is the first college-level productionI’ve directed,” Manson says, “and Itreat it—and Neal—the way I would anyother process or actor. [His work is] of avery high level. He has raw talent, and hetakes direction extremely well. All he needsis experience.”Dandade’s previous honors preparationin theater was Mango Chutney on Mesa Street,an autobiographical solo play, which he createdand performed to excellent reviews inFebruary.“Neal came to me several years ago andwanted to study theater in India,” AssistantProfessor of Theater and Dandade’s adviserErin Mee says. “So I put him in touch withKavalam Narayan Panikkar, one of India’smost famous directors, with whom I haveworked. Neal came back overflowing withnew ideas about theater. He wanted to putsome of those ideas to work in a solo pieceabout growing up in El Paso. I gave himsome assignments for the summer and hireda director [solo actress and director MariaMöller] to work with him. This resulted inMango Chutney, a brilliant and moving pieceof theater.”For relaxation, Dandade performsimprov comedy with Vertigo-Go and has cohosteda WSRN radio show. He is a memberof the Southeast Asian society DESHI andserves as a campus tour guide.Associate Professor and Chair of TheaterStudies Allen Kuharski says: “Neal is a greatexample of what can happenat Swarthmore:For my LatinAmerican Politicsseminarwith ProfessorSharpe,we received a40-pagesyllabus.He’s graduatingfrom the Honors Programin theater, and he also got greatscores on his MCATs.”IN TROTTER HALL, students gather in theRoland Pennock Seminar Room for Professorof Political Science Carol Nackenoff’sConstitutional Law seminar. There are 12 ofthem—a large seminar group, but, with 60percent of all political science majors in theHonors Program, this is not surprising.“I’m getting scoliosis from carrying allthe reading material for this class,” onestudent jokes.“How many trees do you think werekilled for honors seminars?” anotherstudent wonders.Abena Mainoo ’06, an honors politicalscience major and honors French minorfrom Ghana, sits quietly, organizing materialsfor her oral argument in today’s mootcourt session. The students will argue thecase LULAC v. Perry, examining the constitutionalityof the 2003 controversial redrawingof the Texas congressional map thathelped Republicans to win 21—up from15—of the state’s 32 seats in Congress.Mainoo has chosen the role of counsel forthe defense, representing the state of Texasand Governor Rick Perry—“to see how I’lldo arguing for a side I’m not naturally sympatheticwith,” she says.Nackenoff calls the court to order with agavel, and Mainoo, dressed in a smart blackpants suit, steps to the podium. Clearly andconcisely, she argues that Texas is not guiltyof unconstitutional mid-decade redistricting,racial and political gerrymandering,and voter dilution. Calmly assured, sheanswers questions from the other “justices.”Kristin Davis ’06, in a white pants suit,presents opposing arguments. Afterward,both have the opportunity for rebuttal. Aloud and lively discussion ensues, untilNackenoff calls a 15-minute recess forsnacks. Scheduled from 1 to 5 p.m., thisclass almost always lasts until 6 p.m.The court decides in Mainoo’sfavor on the counts of racial and politicalgerrymandering and vote dilutionbut determines that mid-decaderedistricting was unconstitutional.“I was extremely impressed withAbena’s formal presentation,”Nackenoff says. “It was very professional,very rigorous. She had a really goodinstinct how to pitch it. None of the questionsthrew her, and she was able to craftreally good answers. She’d make an excellenttrial lawyer.”Stoical about the staggering workloadaccompanying honors seminars, Mainoosays: “For my Latin American Politics seminarwith Professor Ken Sharpe, we receiveda 40-page syllabus. We had to presentpapers every week. The class went from7 p.m. to midnight or 1 a.m. Sometimes, Igot sleepy, but it was always really interesting.The seminars just go as long as theygo.” Instead of grading the students’ papers,Sharpe writes one-page, letter-style critiquesof their work. “He indicated things he likedand those I could improve on,” Mainoosays. “It was a kind of correspondence withhim, and he always offered constructive crit-september 2006 : 25

The Evolution of HonorsSince 1922, when College President Frank Aydelotte first introducedit, Swarthmore’s Honors Program, based on the Oxford tutorialmodel and arguably the oldest such program in the country, has undergoneseveral revisions. The most recent was in 1996, after the numberof participants reached its lowest ebb at 10 percent of the studentbody.“Despite changes over the decades, the essence of the programremains the same,” affirmed Professor of English Literature and ProgramCoordinator Craig Williamson. Seminars still form the backboneof the program. Whether in classrooms, labs, or research contexts,students take responsibility for leading discussions“Honors students atSwarthmore need tohave an awful lot ofstamina, just to be ableto cover the tremendousamount of work. Theyhave to be dedicatedto learning—really drivenby curiosity for knowledgeand the wish to doresearch and to think.”—Cynthia Halpern, associateprofessor of political scienceand critiquing each other’s work. Dialogue flowsback and forth between students and faculty. Andthe program culminates in external examinationsadministered by invited scholars, who determinewhether a student receives honors, high honors, orhighest honors.In 1996, the number of required honors preparationswas set at four—three in the major and one inthe minor. The restructuring made the program moreaccessible and attractive to students and opened theway for the departments that had dropped out ofthe system to reenter. For these departments, relyingonly on 2-credit seminars had become inconsistentwith the breadth of the disciplinary preparationthey felt responsible to offer. The revised structureallows courses to be combined to create honorspreparations and welcomes in-depth research and honors theses, whichtypically demand an entire academic year of work.The structure also enables students to be examined in foreign studyand community-based projects, encourages interdisciplinary combinationsof majors and minors, and invites participation by the creativearts in the form of poetry portfolios, theater productions, musicalcompositions, and art exhibits. Every academic department of the College—includingall the sciences and engineering—now participates.The revision also includes a change in the grading policy. Underthe former system, students were not graded in honors seminars inorder to further the spirit of student-teacher collaboration in preparingfor the outside examiners. However, as students became increasinglyaware of the importance of grades for acceptance into graduateand professional schools, many were discouraged from enrolling. Since1996, Swarthmore professors award grades in the honors preparations,and the outside examiners confer honorifics. To ensure the pre-eminentrole of the Honors Program, “distinction in course” is no longerawarded by the College.“I think the camaraderie in the seminars was never largely sustainedby the lack of grades. Rather, that sense of camaraderie is builtby the sense of responsibility that we, as teachers, give to students,the respect we give them in terms of this dialogic model, and the reallove of learning and testing of ideas that goes on in the seminars,”Williamson says.This year, 130 external examiners came to campus to evaluate thework of 114 honors candidates, constituting 33 percent of the seniorclass. Ten received highest honors; 64, high honors; and 40, honors.“The outside examiners love our students and are very impressedwith them,” Williamson says. He adds that Swarthmore faculty membersrelish not only the opportunity to exchangenew ideas but also the chance to show the qualityof their students and the program.“For 84 years, the Honors Program has embodiedthe College’s commitment to the rigor, joy, and significanceof the finest liberal arts education,” saidPresident Alfred H. Bloom, “and the 1990s revisionhas had a dramatically positive effect in energizingand sustaining the program in a very differentworld. Grades have become necessary to ensure thatour students are not disadvantaged in graduate andprofessional school admission. The subject matter ofmany disciplines that could not be segmented into2-credit seminars is effectively accommodated, andresearch projects, theses, foreign study, communitybasedinitiatives, and the creative arts all havetaken their rightful place in the program.“Our graduates who have participated in this Honors Programinvariably count their experiences—particularly their interactions withthe external examiners—to be among the most formative experiencesof their lives, moments that reaffirm for a lifetime their confidence toset the highest standards for themselves and to chart their own intellectualpaths.”Assistant Professor of Politics Kenneth Kersch of Princeton, who for2 years has served as the outside examiner for Professor of PoliticalScience Carol Nackenoff’s Constitutional Law seminar, offers an outsideperspective: “The Swarthmore Honors Program in many ways resemblesthe Ph.D. qualifying exams we give to our students at Princeton. Iwrite both exams and orally examine both Swarthmore and my Ph.D.students at about the same time of year. The Swarthmore students areevery bit as good as my graduate students—a testament to both themand their teachers. I find that I am able to use the same pool of questionsfor both exams. I also enjoy the opportunity to spend time withmembers of the political science faculty at Swarthmore during myvisit—a very interesting and enjoyable group of people.”—C.B.D.icism. It was definitely not about grades.”Mainoo says that the frequent presentationsrequired in the honors seminars havebuilt up her self-confidence in oral performance,especially in French; writing weeklypapers has improved her writing; thetremendous amount of reading has helpedher learn to “skim” proficiently; and throughstudying in groups with her seminar mates,she has made new friends and learned newperspectives.Working out and running for fun withfriends helps relieve stress. She has been amember of the Swarthmore African StudentsAssociation, has participated in theChester Debate and the Chinatown Tutorial,and has worked for 11 hours a week in anumber of campus offices.CLASSES ARE OVER ON APRIL 28. In thedays preceding their honors exams, Fiedler,Graybill, Dandade, and Mainoo are quietlyconfident.Fiedler has a plan to ensure that he canreview everything by exam time. His mainchallenge is in preparing for Real Analysis.“I took the course in my sophomore year, soit’s the most distant,” he says. For math, he26: swarthmore college bulletin