SWARTHMORE

Swarthmore College Bulletin (September 2000) - ITS

Swarthmore College Bulletin (September 2000) - ITS

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

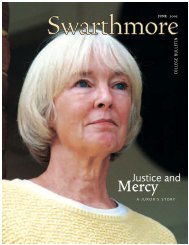

throw them out, and maybe you wouldwin. But I’ll tell you, there will be somereciprocal bleeding up here.”She said, “The interview is over.”The black students asked me why Iwanted to teach here. They weresmart. I said I didn’t particularly wantto come until I had seen them on television,and I thought they neededsomebody like me. That really waswhy I came to Swarthmore. It was1970, there still wasn’t one African-American professor on the faculty.I fully expected not to get an offer.Before I left that day, I said to HarrisonWright, “You’ve got some problems uphere.” He was a fair person. I told him Iwasn’t interested in the position. But Iwas also thinking Swarthmore was themost beautiful campus I had ever seen.Harrison said, “I really do understand.”He knew if he offered me the position Iwouldn’t take it. So I went home andforgot about Swarthmore College. ThenI got a telephone call. Harrison Wrighthad asked the head of the Black Students’Association to offer me the positionin the History Department.I asked, “Well, why didn’t he call mehimself?”She said, “Because he felt that if hecalled you, you wouldn’t accept theposition, but if we called you, youmight accept the position.”I realized I was probably the firstand only African-American professorthe College had ever hired in 106 years!Now, they had a couple of African professorsup here who, if they didn’tbehave, they could send back toAfrica, but they couldn’t send me backto Philly. You understand? There’s adifference [laughing]! It’s to their creditthat they wanted me—because I didn’tpull any punches. I was letting themknow I was someone who would disturbthe peace of racism. And theyoffered me the position. How do I knowwhy? There were some very radicalpeople up here at that time. I had alliesfrom the very beginning.I taught one course at Swarthmorein 1970. Then, I accepted a position inthe English Department at the Universityof Delaware and went back toSwarthmore as an assistant professorwith a three-year appointment. Theytold me it was not sure I would gettenure with my next appointment, andI accepted that. I said yes because Ididn’t know what I was doing. I had noidea how very political and very racistSwarthmore could be. Yes, some peopleat Swarthmore would not believehow racist it really is. Yes, I’m saying it,yes. They do not understand thedynamics of racism, how deep it goes,and how I understand it on an entirelydifferent level.For example, when I moved into myapartment [30 years ago], I was theonly African American in the building[Strath Haven Condominiums] and stilltoday there is only one other African-American couple living here. The swimclub in town did not allow blacks inthe pool when I first moved here, andthey had to desegregate that. Theseare the kinds of things most of thewhite students and faculty never haveto put up with, but we African Americansknow.ONE OF THE PEOPLEON THE INTERVIEWCOMMITTEE SAID TOME, “I KNOW MOREABOUT NEGROESTHAN MOST PEOPLE.”I SAID, “REALLY?”There were also other differences.My people don’t come from money,but several of my colleagues in the HistoryDepartment had family money. Ihad more in common with the blackpeople who came to clean, cook, andserve at Swarthmore College. Butwhen I first came to Swarthmore andwas looking for black community, Ifound that they didn’t want to be tooclose to me. Some of them were makingbelow minimum wage after 25years, you see? So I joined a group offaculty who were trying to get themunionized so they could get bettersalaries. The attempt failed becausethe black workers voted it down. Theywere afraid they were going to losetheir jobs. But some of those peoplereally took pride in everything I did.One, in particular, would come out atgraduation and say, “Kathryn, yougonna wear your gown?” I would do itbecause it mattered to her. Most ofthem I had deep respect for, and theyhad deep respect for me.Being African American at Swarthmore,you almost have to fight foryour identity every single day. For me,as a professor, it’s different from a studentbecause a student has other studentsto relate to. I had no AfricanAmerican colleagues until Jerry Woodwas also hired in the History Departmentsoon after I came. And thenChuck James came into the EnglishDepartment. Both of them are wonderful,talented people, and I was glad tohave them here.So I taught, and my courses werepopular. But there was politics inthe department. Some professors werehostile because they thought oral historyand folklore were not “real” history.They even told students—-whitestudents—-not to take my coursesbecause they weren’t historically valid,and they wouldn’t learn anything.Some students came and disrespectedthe whole thing until they began to listen,and then they grew to love oralhistory and folklore. But it was hard,day by day, to be in a departmentwhere some of your colleagues lookeddown on your field.There were other issues. One femalecolleague, who was the most sincereand nice, told me, “I want you to gettenure in the worst way. I’m going totell you something. Don’t wear thoselong earrings to work, and don’t wearyour hair like that.” I had a naturalhairstyle. “And don’t wear those dressesthat you wear, those long dresses,and those sandals. We don’t wear sandals.”I said, “Look. This is me. This is me,and I am going to be like I am. If youwant black people who look like whitepeople, who act like white people, geta white person! You don’t need a carboncopy of a white person. If you’relooking for diversity, you want the realS E P T E M B E R 2 0 0 021