The Program Evaluation Standards in International Settings

The Program Evaluation Standards in International Settings - IOCE

The Program Evaluation Standards in International Settings - IOCE

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Program</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong><strong>in</strong> <strong>International</strong> Sett<strong>in</strong>gsEdited by Craig RussonPapers byNicole BacmannWolfgang BeywlSaviour ChircopSoojung JangCharles LandertPrachee MukherjeeNick SmithSandy TautThomas Widmer<strong>The</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> CenterOccasional Papers SeriesMay 1, 2000

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Program</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong><strong>in</strong> <strong>International</strong> Sett<strong>in</strong>gsEdited by Craig RussonPapers byNicole BacmannWolfgang BeywlSaviour ChircopSoojung JangCharles LandertPrachee MukherjeeNick SmithSandy TautThomas Widmer<strong>The</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> CenterOccasional Papers SeriesMay 1, 2000

<strong>The</strong> editor acknowledges the valuable assistance of Brian Carnell, Karen Russon, RagnarSchierholz, Sandy Taut, and Sally Veeder <strong>in</strong> the preparation of this manuscript.

Table of ContentsForeword........................................................1Cross-Cultural Transferability of <strong>The</strong> <strong>Program</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong> by SandyTaut............................................................5Considerations on the Development of Culturally Relevant <strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong>by Nick L. Smith, Saviour Chircop and Prachee Mukherjee . . . . . . . . . . . . 29<strong>The</strong> Appropriateness of Jo<strong>in</strong>t Committee <strong>Standards</strong> <strong>in</strong> Non-Western Sett<strong>in</strong>gs :A Case Study of South Korea by Soojung Jang . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41<strong>Standards</strong> for <strong>Evaluation</strong>: On the Way to Guid<strong>in</strong>g Pr<strong>in</strong>ciples <strong>in</strong> German<strong>Evaluation</strong> by Wolfgang Beywl .................................60Evaluat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Evaluation</strong>s: Does the Swiss Practice Live up to <strong>The</strong> <strong>Program</strong><strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong>? by Thomas Widmer .......................67<strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong> Recommended by the Swiss <strong>Evaluation</strong> Society (SEVAL)by Thomas Widmer, Charles Landert, and Nicole Bacmann . . . . . . . . . . . 81Annex: A Summary of the <strong>The</strong> <strong>Program</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong> .............103

ForewordOn February 18-20, 2000, the W. K. Kellogg Foundation-funded residency meet<strong>in</strong>g of regionaland national evaluation organizations took place <strong>in</strong> Barbados, West Indies. Severalorganizations were represented at the meet<strong>in</strong>g: African <strong>Evaluation</strong> Association, American<strong>Evaluation</strong> Association, Asociacion Centroamericana de Evaluacion, Associazione Italiana deValutazione, Australasian <strong>Evaluation</strong> Society, Canadian <strong>Evaluation</strong> Society, European<strong>Evaluation</strong> Society, Israeli Association for <strong>Program</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> (IAPE), Kenyan <strong>Evaluation</strong>Association, La Societe Francaise de l’<strong>Evaluation</strong> (SFE), Malaysian <strong>Evaluation</strong> Society,<strong>Program</strong>me for Strengthen<strong>in</strong>g the Regional Capacity for <strong>Evaluation</strong> of Rural Poverty AlleviationProjects <strong>in</strong> Lat<strong>in</strong> America and the Caribbean (PREVAL), Reseau Ruandais de Suivi et<strong>Evaluation</strong> (RRSE), Sri Lanka <strong>Evaluation</strong> Association (SLEvA), and the United K<strong>in</strong>gdom<strong>Evaluation</strong> Society. In addition, representatives from the W. K. Kellogg Foundation, <strong>The</strong>University of the West Indies, the Caribbean Development Bank, and the United Nations CapitalDevelopment Fund were present.One of the issues around which a lively debate ensued was <strong>The</strong> <strong>Program</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong>(<strong>The</strong> Jo<strong>in</strong>t Committee on <strong>Standards</strong> for Educational <strong>Evaluation</strong>, 1994). <strong>The</strong> Jo<strong>in</strong>t Committee hasalways ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed that <strong>The</strong> <strong>Standards</strong> are uniquely American and may not be appropriate for use<strong>in</strong> other countries without adaptation. Several national evaluation organizations from develop<strong>in</strong>gcountries are anxious to undertake projects to create standards suitable for use <strong>in</strong> their owncultural contexts as a means to guide practice <strong>in</strong> their countries.Some of the evaluation organizations from developed countries were less enthusiastic. <strong>The</strong>yview standards as a barrier to <strong>in</strong>novation. <strong>The</strong>y th<strong>in</strong>k that the word standards implies impositionof best practices. (Develop<strong>in</strong>g countries are not married to the term standards.) Furthermore,they th<strong>in</strong>k that no model can apply to all evaluations. <strong>The</strong> participants at the Barbados meet<strong>in</strong>gpostponed resolution of the issue by say<strong>in</strong>g that it was not appropriate to make a determ<strong>in</strong>ationregard<strong>in</strong>g this matter at the <strong>in</strong>ternational level. Rather, this decision should be made by eachcountry.It is <strong>in</strong> the context of this debate that <strong>The</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> Center is pleased to pr<strong>in</strong>t the seventeenthvolume <strong>in</strong> the Occasional Papers Series entitled, <strong>The</strong> <strong>Program</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong> <strong>in</strong><strong>International</strong> Sett<strong>in</strong>gs. <strong>The</strong> volume conta<strong>in</strong>s six outstand<strong>in</strong>g papers. <strong>The</strong> first paper is entitled“Cross-Cultural Transferability of <strong>The</strong> <strong>Program</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong>” and was written bySandy Taut, a Fulbright scholar at <strong>The</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> Center. In this paper, Taut exam<strong>in</strong>es thetheory beh<strong>in</strong>d the use of <strong>The</strong> <strong>Standards</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational sett<strong>in</strong>gs. She states that <strong>The</strong> <strong>Standards</strong>are values based. Taut then proceeds to exam<strong>in</strong>e several value dimensions such as<strong>in</strong>dividualism-collectivism, hierarchy vs. egalitarianism, etc. F<strong>in</strong>ally, she applies the previouslydiscussed value dimensions to each of the 30 <strong>Program</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong>.<strong>The</strong> second paper, entitled “Considerations on the Development of Culturally Relevant<strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong>,” was written by Nick Smith, Saviour Chircop, and Prachee Mukherjee.

2This article orig<strong>in</strong>ally appeared <strong>in</strong> Studies <strong>in</strong> Educational <strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>in</strong> 1993. (Many thanks toElsevier Science for permission to repr<strong>in</strong>t.) It is one of the earliest attempts to look at theapplication of <strong>The</strong> <strong>Standards</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational sett<strong>in</strong>gs—one referenced by most of the otherpapers <strong>in</strong> the monograph. With<strong>in</strong> the contexts of Malta and India, the authors explored the extentto which <strong>The</strong> <strong>Standards</strong> could be used as the basis for develop<strong>in</strong>g comparable, culturally relevantstandards for <strong>in</strong>digenous use and the ways they could be modified for use by U.S. evaluators <strong>in</strong>cross-cultural sett<strong>in</strong>gs.<strong>The</strong> third paper is entitled “<strong>The</strong> Appropriateness of Jo<strong>in</strong>t Committee <strong>Standards</strong> <strong>in</strong> Non-WesternSett<strong>in</strong>gs: A Case Study of South Korea” by Soojung Jang. This is the paper for which Jang wonthe student paper competition at the 1999 conference of the American <strong>Evaluation</strong> Association.Jang conducted a workshop on the standards for Korean graduate students and adm<strong>in</strong>istered aquestionnaire to workshop participants. <strong>The</strong> study aimed to establish a framework of advice thatcan be applied to Korean evaluation projects and to guide western evaluators who wish todevelop culturally effective techniques.<strong>The</strong> fourth paper, entitled “<strong>Standards</strong> for <strong>Evaluation</strong>: On the Way to Guid<strong>in</strong>g Pr<strong>in</strong>ciples <strong>in</strong>German <strong>Evaluation</strong>”, was written by Wolfgang Beywl, who translated <strong>The</strong> <strong>Program</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong><strong>Standards</strong> <strong>in</strong>to German. This paper was orig<strong>in</strong>ally published <strong>in</strong> a 1999 volume of the German<strong>Evaluation</strong> Society’s newsletter. It’s purpose was to <strong>in</strong>itiate development of a unique set ofGerman evaluation standards.<strong>The</strong> fifth paper is entitled “Evaluat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Evaluation</strong>s: Does Swiss Practice Live Up to <strong>The</strong><strong>Program</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong>?” by Thomas Widmer. This is a paper that Widmer presented atthe historic <strong>International</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> Conference that was held <strong>in</strong> 1995 <strong>in</strong> Vancouver, BritishColombia. In the paper, Widmer presents the results of a metaevaluation of 15 Swiss programsthat he conducted us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>The</strong> <strong>Standards</strong>. Recommendations are also <strong>in</strong>cluded for adapt<strong>in</strong>g <strong>The</strong><strong>Program</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong> to the Swiss context. This paper forshadowed the importantefforts carried out by the Swiss that are detailed <strong>in</strong> the last paper.<strong>The</strong> sixth, and last paper, is entitled “<strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong> Recommended by the Swiss<strong>Evaluation</strong> Society (SEVAL)” by Thomas Widmer, Charles Landert, and Nicole Bacmann. Inthis paper discusses the evaluation standards developed by SEVAL. <strong>The</strong>se standards are <strong>in</strong> partbased on <strong>The</strong> <strong>Program</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong>. This is an historic first. <strong>The</strong>se are the firstevaluation standards to be developed <strong>in</strong> a country outside of the USA. <strong>The</strong> experience of theSwiss may be a model for other countries to follow.Analysis of the f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs of the three empirically based papers (see Table 1) shows a substantialamount of agreement among Smith et. al. and Jang on the difficulty of apply<strong>in</strong>g the Propriety<strong>Standards</strong> <strong>in</strong> Malta, India, and Korea. Widmer found less difficulty with the Propriety standards<strong>in</strong> Germany. Perhaps the sense of propriety <strong>in</strong> a Western country such as Germany is closer tothat found <strong>in</strong> the USA than is the sense of propriety found <strong>in</strong> non-Western countries such asMalta or India.

Hopefully, this volume will contribute to the understand<strong>in</strong>g of applications of <strong>The</strong> <strong>Program</strong><strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational sett<strong>in</strong>gs. Evaluators outside the USA should not hesitateto use the <strong>Standards</strong> they feel are appropriate. Someday these evaluators may wish to undertakethe task of develop<strong>in</strong>g their own culturally relevant standards. Should they wish to do this, theprocess followed by the Jo<strong>in</strong>t Committee for <strong>Program</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong> (Russon, 1999) maybe a helpful guide.3

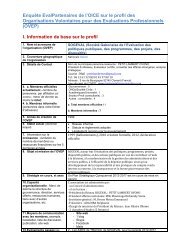

4Table 1: Comparison of F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs From Three Empirical PapersStandard Smith Jang WidmerU1 Stakeholder Identification XU2U3U4U5U6U7F1F2Evaluator CredibilityInformation Scope and SelectionValues IdentificationReport ClarityReport Timel<strong>in</strong>ess and Dissem<strong>in</strong>ation<strong>Evaluation</strong> ImpactPractical ProceduresPolitical ViabilityF3 Cost Effectiveness XP1 Service Orientation X XP2 Formal Agreements XP3 Rights of Human Subjects X XP4 Human Interactions XP5 Complete and Fair Assessment XP6 Disclosure of F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs X XP7 Conflict of Interest X XP8A1A2A3Fiscal Responsibility<strong>Program</strong> DocumentationContext AnalysisDescribed Purposes and ProceduresA4 Defensible Information Sources X XA5 Valid Information XA6A7A8A9Reliable InformationSystematic InformationAnalysis of Quantitative InformationAnalysis of Qualitative InformationA10 Justified ConclusionsA11 Impartial Report<strong>in</strong>gA12 MetaevaluationX

5Cross-Cultural Transferabilityof <strong>The</strong> <strong>Program</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong>“ . . . there is no such th<strong>in</strong>g as human nature <strong>in</strong>dependent of culture” (Geertz,1973)Sandy TautVisit<strong>in</strong>g Scholar<strong>The</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> CenterAbstract<strong>The</strong> paper addresses the cross-cultural transferability of <strong>The</strong> <strong>Program</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong><strong>Standards</strong> (Jo<strong>in</strong>t Committee on <strong>Standards</strong> for Educational <strong>Evaluation</strong>, 1994).Based on cross-cultural psychological and anthropological literature, culturalvalues are identified and discussed for each of the 30 standards. Examples aregiven as to the cross-cultural differences regard<strong>in</strong>g these values. <strong>The</strong> analysis<strong>in</strong>cludes a review of the relevant literature deal<strong>in</strong>g with the standards’transferability. <strong>The</strong> author concludes that Utility and Propriety <strong>Standards</strong>, <strong>in</strong>particular, have limited applicability <strong>in</strong> cultures differ<strong>in</strong>g from their NorthAmerican orig<strong>in</strong>. Hence, evaluators from other cultural contexts should be awareof the underly<strong>in</strong>g values limit<strong>in</strong>g the standards’ cross-cultural applicability.

6 Sandy TautIntroduction<strong>The</strong> purpose of this paper is to analyze the cross-cultural applicability of <strong>The</strong> <strong>Program</strong><strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong> (Jo<strong>in</strong>t Committee on <strong>Standards</strong> for Educational <strong>Evaluation</strong>, 1994). Aspecial emphasis is placed on the <strong>Standards</strong>’ implicit cultural values because these values makethe transfer of the <strong>Standards</strong> to other value contexts (i.e., cultures) difficult. In cross-culturalpsychological literature, the concept of standards is used to def<strong>in</strong>e values, e.g., as Smith andSchwartz (1997) put it, "values serve as standards to guide the selection or evaluation ofbehavior, people, and events" (<strong>in</strong>: Berry, Segall & Kagitibasi (ed.), 1997, Vol. 3, p. 80).Accord<strong>in</strong>g to Peoples and Bailey’s (1994) sem<strong>in</strong>al anthropological textbook, values are def<strong>in</strong>edas “provid<strong>in</strong>g the ultimate standards that people believe must be upheld under practically allcircumstances” (p. 28). In addition, Smith and Schwartz (1997; <strong>in</strong>: Berry et al., Vol. 3, p. 79)state that “[…] value priorities prevalent <strong>in</strong> a society are a key element, perhaps the most central,<strong>in</strong> its culture, and the value priorities of <strong>in</strong>dividuals represent central goals that relate to allaspects of behavior.” <strong>The</strong>se researchers further note that “as standards, cultural value prioritiesalso <strong>in</strong>fluence how organizational performance is evaluated – for <strong>in</strong>stance, <strong>in</strong> terms ofproductivity, social responsibility, <strong>in</strong>novativeness, or support for the exist<strong>in</strong>g power structure”(p. 83).<strong>The</strong> first assumption derived from these statements is that <strong>The</strong> <strong>Program</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong>are values-based. <strong>The</strong> second assumption, supported by a large amount of research on culturalvalues (e.g., see Berry et al., 1997, Vol. 3, chapter 3), is that values differ across cultures:“cultures can be characterized by their systems of value priorities” (p. 80). Members of onecultural group share many value-form<strong>in</strong>g experiences and therefore come to accept similarvalues.<strong>The</strong> discrepancy <strong>in</strong> values is not only apparent between the North American and other culturesaround the world, but also, for example, with<strong>in</strong> the United States. <strong>The</strong>re, one can identify somecultural subgroups whose values deviate from "ma<strong>in</strong>stream America," e.g., Native Americans(see Miller, 1997; <strong>in</strong>: Berry et al., 1997, Vol. 1, p. 105).In contrast to values, norms are “shared ideals (rules) about how people ought to act <strong>in</strong> certa<strong>in</strong>situations, or […] toward particular other people” (Peoples & Bailey, 1994, p. 28). Norms arebased on values. In some of the <strong>Standards</strong> (e.g., Formal Agreements), the more concrete normsare reflected <strong>in</strong> lieu of the higher-level values.When analyz<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>Program</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong> it seems important to refer to the Jo<strong>in</strong>tCommittee's def<strong>in</strong>ition of standards and to address the Jo<strong>in</strong>t Committee's conclusions regard<strong>in</strong>gtheir level of generality (across cultures and even with<strong>in</strong> North America). <strong>The</strong> Jo<strong>in</strong>t Committee(1994) def<strong>in</strong>es a standard as “a pr<strong>in</strong>ciple mutually agreed to by people engaged <strong>in</strong> a professionalpractice, that, if met, will enhance the quality and practice of that professional practice, forexample, evaluation” (p. 2). <strong>The</strong> Jo<strong>in</strong>t Committee acknowledges “that standards are not allequally applicable <strong>in</strong> all evaluations” (p. 2), that they are “guid<strong>in</strong>g pr<strong>in</strong>ciples, not mechanical

Cross-Cultural Transferability of the <strong>Program</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong> 7rules” (p. 8) and, implicitly, that they are based on North American values: “<strong>The</strong>y [the<strong>Standards</strong>] def<strong>in</strong>e contemporary ideas of what pr<strong>in</strong>ciples should guide and govern evaluationefforts” (pp. 17-18). In a section on guidel<strong>in</strong>es for application of the <strong>Standards</strong>, the third step isto “clarify the context of the <strong>Program</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong>” (p. 11), the cultural context unquestion<strong>in</strong>glybe<strong>in</strong>g of major importance. Stufflebeam (1986), Chair of the Jo<strong>in</strong>t Committee from its birth <strong>in</strong>1975 until 1988, notes that “their [the <strong>Standards</strong>’] utility is limited, especially outside the UnitedStates” (p. 18). Evaluators have called for more research on their transferability (e.g., Nevo,1984, p. 386). <strong>The</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g paper is an <strong>in</strong>vestigation along this dimension.With evaluation recently becom<strong>in</strong>g a stronger professional field <strong>in</strong> many countries, <strong>Standards</strong> forprofessional conduct also become an important issue. <strong>The</strong> process of develop<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Standards</strong> iseffortful and cost-<strong>in</strong>tensive (see Jo<strong>in</strong>t Committee, 1994, pp. xvi-xviii; Stufflebeam, 1986, pp. 2).<strong>The</strong>refore, it is only logical that evaluators from different countries turn to the <strong>Program</strong><strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong> as a model for their own work. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Standards</strong> have been translated <strong>in</strong>toGerman, after Beywl (1996, 1999) concluded that – with m<strong>in</strong>or adaptations – they aretransferable to the German cultural context. <strong>The</strong> Swiss <strong>Evaluation</strong> Society developed <strong>Standards</strong>closely follow<strong>in</strong>g the North American model (see SEVAL-<strong>Standards</strong>, Schweizerische<strong>Evaluation</strong>sgesellschaft, 1999). However, the Schweizerische <strong>Evaluation</strong>sgesellschaft did notspecifically address the degree of transferability of the <strong>Standards</strong>. Neither did the Spanishtranslation of the <strong>Standards</strong> (Villa, 1998). Dur<strong>in</strong>g a 1998 UNICEF <strong>Evaluation</strong> Workshop <strong>in</strong>Nairobi, Kenya, a focus group discussion dealt with the applicability of the <strong>Standards</strong> <strong>in</strong> Africancultures (Russon & Patel, 1999, p. 4). Of the n<strong>in</strong>e African evaluators, the majority found the<strong>Standards</strong> to be transferable if some modifications were undertaken. In their eyes, the <strong>Standards</strong>are not laden with values <strong>in</strong>compatible with African values. Dur<strong>in</strong>g the discussion, theparticipants suggested adaptations of twelve <strong>Standards</strong> (see Russon & Patel, 1999, pp. 5). Am<strong>in</strong>ority held that African Evaluators should develop their own <strong>Standards</strong>. <strong>The</strong> <strong>Standards</strong> havealso been used <strong>in</strong> Israel (see Nevo, 1984; Lewy, 1984), Brazil (see Rodrigues de Oliveira &Gomes-Elliot, 1983), and Sweden (see Marklund, 1984). <strong>The</strong>se authors conclude that theimportation of the <strong>Standards</strong> requires at least some adaptation to fit the host culture but <strong>in</strong> fewcountries has the transferability issue been addressed <strong>in</strong> detail. Consequently, an <strong>in</strong>-depthanalysis of the <strong>Standards</strong>’ general cross-cultural transferability is crucial and overdue.<strong>The</strong> present paper does not <strong>in</strong>vestigate the likelihood that various cultures meet the <strong>Standards</strong>based on their cultural idiosyncrasies. Instead, the values the <strong>Standards</strong> are based on will beexam<strong>in</strong>ed. It will be shown that <strong>in</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> cultures these values may limit the applicability of the<strong>Standards</strong> as guid<strong>in</strong>g pr<strong>in</strong>ciples for evaluators (see Beywl, 1999; Smith et al., 1993; Jang, 2000).In this context, it is important to differentiate between <strong>in</strong>digenous <strong>Standards</strong> emerg<strong>in</strong>g fromwith<strong>in</strong> different cultures, cross-cultural <strong>Standards</strong> <strong>in</strong>tended for evaluators work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> similarcultures (or with multicultural stakeholders), and ubiquitous <strong>Standards</strong> <strong>in</strong>tended to fit allcultures. <strong>The</strong> latter <strong>Standards</strong> might need to be highly general or vague to fit all possiblecontexts, which likely results <strong>in</strong> less specific direction and therefore less utility of these<strong>Standards</strong>. As po<strong>in</strong>ted out above, <strong>Standards</strong> are per se values-based and therefore culturespecific.Consequently, it seems that ‘cover<strong>in</strong>g up’ their orig<strong>in</strong> by add<strong>in</strong>g statements that stressgenerality can only work at the expense of the <strong>Standards</strong>’ effectiveness as guid<strong>in</strong>g pr<strong>in</strong>ciples.

8 Sandy Taut<strong>The</strong>re is evidence to support the Jo<strong>in</strong>t Committee's recommendations that care has to be takenwhen apply<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>Standards</strong> as goals for professional conduct outside the North American(‘ma<strong>in</strong>stream’) cultural context.<strong>The</strong> cross-cultural psychological and anthropological literature revealed values reflected <strong>in</strong> the<strong>Program</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong>. Researchers from these fields exam<strong>in</strong>e cultural value dimensionsand a number of other concepts as a way to describe and differentiate cultures. <strong>The</strong> culturaldimensions and concepts used for the analysis of the <strong>Standards</strong> will be expla<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> more detail<strong>in</strong> the follow<strong>in</strong>g chapter.A Summary of Relevant Cultural Value DimensionsCross-cultural psychologists commonly dist<strong>in</strong>guish seven culture areas, namely, WestEuropean, Anglo, East European, Islamic, East Asian, Lat<strong>in</strong> American, Japanese (Berry et al.,Vol. 3, p. 105). This dist<strong>in</strong>ction obviously displays a simplified view of the true diversity andnumber of cultures all over the world.As mentioned earlier, cross-cultural literature uses cultural value dimensions tocategorize differences between societies. For example, one of the most widely used andresearched categories is the Individualism-Collectivism dimension. This cultural dimension hasalso been employed by Smith et al. (1993, p. 12) to expla<strong>in</strong> difficulties <strong>in</strong> the applicability of the<strong>Standards</strong> <strong>in</strong> India and Malta. Some additional common dimensions <strong>in</strong>clude Egalitarianism-Hierarchy (or Power Distance), Conservatism-Autonomy and Mastery-Harmony. Empiricalstudies show that these dimensions are valid and reliable (see Berry et al., 1997, Vol. 3). Thispaper will briefly describe these dimensions, followed by a description of other relevant culturalconcepts used <strong>in</strong> this analysis.Individualism-CollectivismPhilosophic trends beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g with Descartes, followed by British empiricism (Hobbes,Smith), social Darw<strong>in</strong>ism (Spencer), phenomenology and existentialism (Kierkegaard, Husserl,Heidegger, Sartre) made <strong>in</strong>dividualism the hallmark of European social history s<strong>in</strong>ce thethbeg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g of the 16 century (see Berry et al., 1997, Vol. 3, p. 4). In contrast, eastern religionsand philosophies such as Confucianism, Taoism, Buddhism, H<strong>in</strong>duism and Sh<strong>in</strong>toism can beseen as roots of collectivism <strong>in</strong> these cultural sett<strong>in</strong>gs. Early monotheistic religions aris<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> theMiddle East (Judaism, Christianity, Islam) also emphasize collective loyalties. However, thethEuropean Reformation <strong>in</strong> Christianity (16 century) later <strong>in</strong>troduced <strong>in</strong>dividual responsibility(see Berry et al., 1997, Vol. 3, p. 5). Kagitcibasi (1997, <strong>in</strong>: Berry et al., Vol. 3, p. 5) states that“all societies must deal with tensions between collectivism and <strong>in</strong>dividualism, […] there is someof both everywhere. Nevertheless, differences <strong>in</strong> emphasis appear to be real.”Hofstede (1980) provided a more recent appraisal of the collectivist-<strong>in</strong>dividualistdist<strong>in</strong>ction. He conducted a survey on work-related values with 117,000 IBM-employees from40 (later expanded to 50) countries. A factor analysis revealed four value dimensions:

Cross-Cultural Transferability of the <strong>Program</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong> 9‘Uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty Avoidance,’ ‘Mascul<strong>in</strong>ity,’ ‘Power Distance’ and ‘Individualism-Collectivism.’Hofstede’s (1980, pp. 260f) orig<strong>in</strong>al def<strong>in</strong>itions of the those last two concepts read as follows:“Individualism stands for a society <strong>in</strong> which the ties between <strong>in</strong>dividuals are loose; everyone isexpected to look after himself or herself and his or her immediate family only”; “Collectivismstands for a society <strong>in</strong> which people from birth onwards are <strong>in</strong>tegrated <strong>in</strong>to strong, cohesive<strong>in</strong>groups, which throughout people’s lifetime cont<strong>in</strong>ue to protect them <strong>in</strong> exchange forunquestion<strong>in</strong>g loyalty.”Triandis’ research (1990, p. 113) elaborated on Hofstede’s work. Triandis notes that thedef<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g attributes of <strong>in</strong>dividualism are “distance from <strong>in</strong>groups, emotional detachment, andcompetition,” while he characterizes collectivism as stress<strong>in</strong>g “family <strong>in</strong>tegrity and solidarity.”Based on empirical f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs, Schwartz (1990, 1994a,b) ref<strong>in</strong>ed the <strong>in</strong>dividualism-collectivismdimension with two higher order dimensions. At the cultural level, these dimensions are‘Autonomy vs. Conservatism’ and ‘Hierarchy vs. Egalitarianism.’ Elaboration on the behavioraldifferences based on the collectivism-<strong>in</strong>dividualism dimension and their relation to the analysisof the <strong>Standards</strong> will be provided <strong>in</strong> a later section of this paper.Similar to Hofstede (1980), Schwartz (1994a,b) conducted a value survey <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g44,000 respondents (us<strong>in</strong>g teachers and students) from 56 countries. After statistical analyses ofthe data he proposed the follow<strong>in</strong>g three cultural level value dimensions.Conservatism-Autonomy<strong>The</strong> Conservatism-Autonomy dimension addresses the relations between <strong>in</strong>dividual andgroup. At the conservatism pole, people are strongly embedded <strong>in</strong> a collectivity – similar to thedef<strong>in</strong>ition of collectivism. Schwartz adds the notion of “social order, respect for tradition, […]and self-discipl<strong>in</strong>e” (Berry et al., 1997, Vol. 3, p. 99) to this concept. People <strong>in</strong> highlyautonomous cultures “f<strong>in</strong>d mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> […their] own uniqueness”; they are encouraged toexpress their own preferences, feel<strong>in</strong>g, motives etc. (Berry et al., Vol. 3, p. 99).Hierarchy vs. EgalitarianismWith this dimension, Schwartz (1994a) describes how cultures differ <strong>in</strong> their way tomotivate people to display responsible social behavior. In highly hierarchical societies (e.g.,Japan), a system of ascribed roles assures socially responsible behavior. People learn to complywith the demands attached to their roles and to see an unequal distribution of power, roles andresources as legitimate. In contrast, highly egalitarian cultures (e.g., Sweden) conta<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividualswho are equals and who are socialized to voluntarily cooperate with others (Berry et al., 1997,Vol. 3, p. 100).Mastery vs. HarmonySchwartz’s (1994a) third dimension deals with the role people play <strong>in</strong> the natural andsocial world. In high Mastery cultures, people seek to control and change the natural and social

10 Sandy Tautworld and exploit it <strong>in</strong> order to further personal or group <strong>in</strong>terests. Values <strong>in</strong>clude ambition,success, and competence. High Harmony cultures accept the world as it is and try to preserve itrather than to change or to exploit it (Berry et al., 1997, Vol. 3, p. 100).Uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty AvoidanceHofstede (1980, p. 110) describes this dimension based on three <strong>in</strong>dicators, “ruleorientation, employment stability and stress level.” In an extension of Hofstede’s research, Bond(1987) found some evidence that underm<strong>in</strong>es the universality of this cultural value (Berry et al.,1997, Vol. 3, p. 99), but at the same time his study replicated Hofstede’s other three dimensions.However, other researchers have cont<strong>in</strong>ued to use the uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty avoidance dimension.Other cross-cultural psychological concepts used here to describe differences betweencultures are:Direct vs. Indirect CommunicationGenerally, direct communication predom<strong>in</strong>ates <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividualistic cultures whereascollectivist societies communicate <strong>in</strong>directly (Gudykunst & T<strong>in</strong>g-Toomey, 1988). Selfdisclosure(giv<strong>in</strong>g personal <strong>in</strong>formation to others they don’t know) is associated with directcommunication styles. A crucial variable <strong>in</strong> collectivist cultures is whether communicationoccurs with members of the <strong>in</strong>group or with members of an outgroup; communication will bemore direct (more self-disclosure) among <strong>in</strong>group members compared to communication withoutgroup members. In contrast, there are no differences <strong>in</strong> self-disclosure between <strong>in</strong>group andoutgroup <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividualistic cultures (Gudykunst et al., 1992).High-Context vs. Low-ContextClosely related to the above mentioned communication issue is the dist<strong>in</strong>ction betweenhigh-context and low-context cultures. Members of collectivist cultures emphasize theimportance of context <strong>in</strong>formation <strong>in</strong> expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g others’ behavior more than people <strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>dividualistic cultures. This also makes adapt<strong>in</strong>g to the context an important part of highcontextcommunication patterns prevalent <strong>in</strong> collectivist cultures. In addition, Uncerta<strong>in</strong>tyAvoidance (UA, see above) <strong>in</strong>fluences the degree to which communication follows rules andrituals (high UA means highly ritualistic), especially for outgroup communication/<strong>in</strong>teraction.Lastly, Power Distance (PD) also determ<strong>in</strong>es <strong>in</strong>teraction/communication styles; high PD meanslow levels of egalitarian cooperation between people with different amounts of power. S<strong>in</strong>ceoutgroup members are outsiders, they tend to have less power than <strong>in</strong>siders (see Berry et al.,1997, Vol. 3, p. 142).

Cross-Cultural Transferability of the <strong>Program</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong> 11Seniority‘Seniority’ generally refers to the level of one’s social stand<strong>in</strong>g based on one’s age. Incross-cultural organizational psychology, the concept of ‘seniority’ is commonly used todescribe promotion systems. In contrast to <strong>in</strong>dividualistic societies, organizations <strong>in</strong> collectivistcultures base promotion on employees’ loyalty, seniority, and <strong>in</strong>-group membership (Berry et al.,1997, Vol. 3, p. 379).F<strong>in</strong>ally, one needs to address the fact that cultures are constantly chang<strong>in</strong>g over time.<strong>The</strong>re are two ways <strong>in</strong> which cultural change comes about: <strong>in</strong>novation (<strong>in</strong>ternally generatedchange) and diffusion (adopt<strong>in</strong>g traits from another society). People are receptive of new traitswhen these enhance their economic and social well-be<strong>in</strong>g. In addition, political and economicdom<strong>in</strong>ation, as well as environmental and demographic changes can all <strong>in</strong>troduce culturalchanges (see Peoples & Bailey, 1995, p. 105). In an <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly <strong>in</strong>terdependent world (with aglobal economy, immigration flows and world-wide communication), cultural change will likelyhappen more quickly. S<strong>in</strong>ce values are reflective of cultural changes, it is also likely that therewill be value changes <strong>in</strong> the form of adaptations to the chang<strong>in</strong>g environment. Yet, every culturalsett<strong>in</strong>g is unique, thus mak<strong>in</strong>g values a cont<strong>in</strong>uously valid way to differentiate cultures (Berry etal., 1997, Vol. 3, p. 110).<strong>The</strong> Role of Professional <strong>Standards</strong> Across Cultures<strong>The</strong> concept of professionalism <strong>in</strong> evaluation differs across cultures. As one componentof this concept, professional standards for enhanc<strong>in</strong>g the quality of evaluators’ performance areof vary<strong>in</strong>g importance <strong>in</strong> different societies. Smith et al. (1993) compare Malta, India and theUnited States along these l<strong>in</strong>es. In the U.S., professional groups historically regulate themselvesthrough professional standards and compliance with self-generated laws and pr<strong>in</strong>ciples has longexisted. In contrast, “[…]<strong>in</strong> Malta and India, the quality of one’s evaluation work is more likelyto be judged on political than on technical or professional grounds. Professional standards wouldplay a much weaker role <strong>in</strong> regulat<strong>in</strong>g evaluation practice […]” (p. 8). <strong>The</strong> authors conclude that“the development and use of <strong>in</strong>digenous professional standards are unlikely, unwelcome, andprobably unuseful” (p. 9). In contrast, for example, Widmer (1999) observes for the Swisscontext that the set of <strong>Standards</strong> proposed by the Swiss <strong>Evaluation</strong> Society (SEVAL) are usedmore and more as part of regulations, manuals, contracts, and decrees. He posits that, <strong>in</strong> theGerman-speak<strong>in</strong>g countries, the <strong>Standards</strong> serve as a means to build a “professionell orientiertesSelbstverstndnis [professionally oriented self-perception]” with<strong>in</strong> the evaluation community (p.8). Beywl (1999) theorizes that the <strong>Standards</strong> will <strong>in</strong>fluence the field of evaluation <strong>in</strong> Germanyalmost from its birth while <strong>in</strong> the U.S. the development of the <strong>Standards</strong> marked the arrival of acerta<strong>in</strong> level of maturity of the field. He advises the German <strong>Evaluation</strong> Society (DeGEval) toendorse an adapted version of the <strong>Standards</strong> as pr<strong>in</strong>ciples for proper conduct. Likewise, Russon& Patel (1999) report from a focus group discussion on the <strong>Program</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong> thatthe n<strong>in</strong>e participat<strong>in</strong>g African evaluators “reached a rapid consensus that there was a need forsome set of criteria of quality” <strong>in</strong> Africa (p. 4).

12 Sandy TautFrom a more general po<strong>in</strong>t of view, we could expla<strong>in</strong> these cultural differences <strong>in</strong> the roleof professional standards us<strong>in</strong>g cultural dimensions and concepts. For example, one could arguethat high-conservatism societies tend to not use <strong>Standards</strong>. In those cultures, the emphasis on thema<strong>in</strong>tenance of the status quo keeps people from engag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> behavior that might disrupt thegroup solidarity(<strong>in</strong> this case the group of evaluators). <strong>The</strong> same may be true for collectivistcultures. In those cultures, a “socially-oriented achievement motivation” (Berry et al., 1997, Vol.3, p. 25) might prevent <strong>in</strong>dividual accountability on the basis of <strong>Standards</strong> to be valued. Incultures with strong <strong>in</strong>groups, “group achievement rather than <strong>in</strong>dividual expertise is valued”(Rohlen, 1979, <strong>in</strong>: Berry et al., 1997, Vol. 3, p. 380). In countries with “Confucian work ethics”(<strong>The</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>ese Culture Connection, 1987, <strong>in</strong>: Berry et al., 1997, Vol. 3, p. 373), work is “a moralduty to the collectivity.”In addition, for example, <strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>a (Chen & Uttal, 1988, <strong>in</strong>: Berry et al., 1997, Vol. 3, p.139), “effort is regarded as more important than ability <strong>in</strong> expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g academic outcomes than <strong>in</strong>the United States.” Extrapolated to the professional context, accountability based on <strong>Standards</strong>of proper conduct seems difficult. Also, <strong>in</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> cultures, the motivation of people to performis lower than <strong>in</strong> others. For example, an underly<strong>in</strong>g assumption of Organizational Developmentis that the organizational members have the motivation “‘to make […] a higher level ofcontribution to the atta<strong>in</strong>ment of organizational goals […].’ [French & Bell, 1990, p. 44]Probably this assumption does not hold true <strong>in</strong> many develop<strong>in</strong>g countries” (<strong>in</strong>: Berry et al.,1997, Vol. 3, p. 394).One should also take <strong>in</strong>to account current and future developments <strong>in</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> acrossthe world. As more <strong>in</strong>digenous evaluators are be<strong>in</strong>g tra<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> western sett<strong>in</strong>gs or by westernevaluators, the <strong>Standards</strong> will probably become more widespread even <strong>in</strong> cultures where theiruse would not come about without such foreign <strong>in</strong>fluence. Additional dissem<strong>in</strong>ation might, ofcourse, come from those western evaluators engaged <strong>in</strong> evaluations <strong>in</strong> foreign cultural sett<strong>in</strong>gs.Even though, <strong>in</strong> some cultures, evaluators do not and will not rely on <strong>Standards</strong> for judg<strong>in</strong>gprofessional performance, the <strong>Standards</strong> can still provide helpful ideas on important aspects ofwhat good evaluations should look like. However, even these ideas need to be relevant to thespecific cultural backgrounds and values, mak<strong>in</strong>g an analysis of their cross-culturaltransferability a sensible task.A Values-Based Analysis of the <strong>Standards</strong>’ Cross-Cultural TransferabilityFor exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the <strong>Standards</strong>’ transferability to other cultures, it is important to analyzethe <strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong> regard<strong>in</strong>g the North American values they reflect, as represented by theJo<strong>in</strong>t Committee members. Values have a vary<strong>in</strong>g degree of generality across cultures. Likevalues, we consider some of the <strong>Standards</strong> as be<strong>in</strong>g universal. <strong>The</strong>se <strong>Standards</strong> (e.g., PracticalProcedures) need no further discussion from a cross-cultural po<strong>in</strong>t of view. Yet other <strong>Standards</strong>(e.g. Rights of Human Subjects) are unique to North American culture and lack transferability toother cultures.

Cross-Cultural Transferability of the <strong>Program</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong> 13What values or value dimensions are reflected <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Standards</strong> and how do these valuesdiffer across cultures? Which are valid <strong>Standards</strong> for evaluators <strong>in</strong> all cultures, and which<strong>Standards</strong> perta<strong>in</strong> to goals of conduct that do not apply <strong>in</strong> cultures different from the NorthAmerican culture?In exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the <strong>Standards</strong>, the complexity of the analysis was restricted by omitt<strong>in</strong>g todiscuss the <strong>in</strong>terdependencies among the <strong>Standards</strong>. By def<strong>in</strong>ition, focus<strong>in</strong>g on one Standard willsometimes mean neglect<strong>in</strong>g another (trade-off, see Stufflebeam, 1986, pp. 10; Jo<strong>in</strong>t Committee,1994, p. 9); some <strong>Standards</strong> form an entity <strong>in</strong> the evaluation process. In addition, as mentionedabove, the Jo<strong>in</strong>t Committee (1994) stresses that the <strong>Standards</strong> are not rigid pr<strong>in</strong>ciples. <strong>The</strong>analysis presented <strong>in</strong> this paper can neither account for all possible situations and cases <strong>in</strong> whichthe <strong>Standards</strong> are used, nor the different ways <strong>in</strong> which they are applied by different evaluators.<strong>The</strong>ir negotiability ameliorates their transferability to other cultural contexts. However, theirnegotiability does not compensate for their reflection of values specific to their orig<strong>in</strong>. Inaddition, an analysis deal<strong>in</strong>g with cultural values is necessarily oriented to ‘ma<strong>in</strong>stream’ values.Societal values are always arranged along a cont<strong>in</strong>uum, some people be<strong>in</strong>g closer to one end,some closer to the other; but the majority will be found <strong>in</strong> the middle. <strong>The</strong> <strong>in</strong>terpretation and useof the <strong>Standards</strong> also occurs along a cont<strong>in</strong>uum which is affected by the evaluator's expertise andvalues and the current context of the evaluation (with<strong>in</strong> a culture). But some degree ofsimplification is necessary to ensure the clarity of the analysis. We concede that the follow<strong>in</strong>ganalysis is based on subjective <strong>in</strong>terpretation of the <strong>Standards</strong> as they appear <strong>in</strong> the secondedition, with all the above mentioned restrictions.A f<strong>in</strong>al remark is dedicated to the ‘Guidel<strong>in</strong>es’ and ‘Common Errors’ sections <strong>in</strong> the<strong>Standards</strong> (Jo<strong>in</strong>t Committee, 1994). We are aware that they were designed as proceduralsuggestions based on the experiences of North American evaluators – they are not <strong>in</strong>tended asgeneral pr<strong>in</strong>ciples applicable <strong>in</strong> any situation (even less than the <strong>Standards</strong> themselves).Nevertheless, some of the observations made when read<strong>in</strong>g these sections through the ‘crossculturallens’ are <strong>in</strong>cluded s<strong>in</strong>ce these remarks might help the reader <strong>in</strong> understand<strong>in</strong>g the valuedimensions that were identified and might also heighten the reader’s awareness regard<strong>in</strong>gcultural <strong>in</strong>fluences dur<strong>in</strong>g the evaluation process.Utility <strong>Standards</strong>U1 Stakeholder Identification Persons <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> or affected by theevaluation should be identified, so that their needs can be addressed.<strong>The</strong> 'Stakeholder' concept is of central importance throughout the <strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong>(it is part of almost all <strong>Standards</strong>), and it is most explicit <strong>in</strong> the Utility Standard U1, StakeholderIdentification. This concept is closely tied to the Hierarchy-Egalitarianism cultural dimension.For example, the <strong>in</strong>clusion of all significant stakeholders <strong>in</strong> the evaluation process is a desirableand legitimate goal <strong>in</strong> Western democratic societies, like the United States, that have anegalitarian understand<strong>in</strong>g of society. In other cultures, people view the unequal distribution of

14 Sandy Tautpower, roles and resources as desirable and legitimate. People are socialized to comply with theirroles and the obligations related to each role. Society often penalizes people for fail<strong>in</strong>g tocomply with the obligations imparted by their social status (Berry et al., 1997, Vol. 3, p. 79).Thus, paradoxically, what the <strong>Standards</strong> list as Common Errors may serve as Guidel<strong>in</strong>es <strong>in</strong> highhierarchy cultures, e.g., when stat<strong>in</strong>g: "Assum<strong>in</strong>g that persons <strong>in</strong> leadership or decision-mak<strong>in</strong>groles are the only, or most important, stakeholders." (Jo<strong>in</strong>t Committee, 1994, p. 26. For example,for South Korea, Jang (2000, p. 10) po<strong>in</strong>ts out that “the project focus is likely to be determ<strong>in</strong>edby the specific client group that supports and controls the project.” Throughout her analysis ofthe applicability of the <strong>Standards</strong> <strong>in</strong> South Korean society, Jang stresses the importance of thefocus on the top client group (see Jang, 2000, pp. 10) and she concludes that “evaluators […]need to meet only the immediate stakeholder’s expectations” (p. 24).U2 Evaluator Credibility <strong>The</strong> persons conduct<strong>in</strong>g the evaluation shouldbe both trustworthy and competent to perform the evaluation, so that the evaluationf<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs achieve maximum credibility and acceptance.<strong>The</strong> second Utility Standard U2, Evaluator Credibility, also touches upon culturallyrelevant value dimensions. As po<strong>in</strong>ted out before by Smith et al. (1994, p. 7), the concept of aprofessional differs across cultures (e.g., between Malta, India, and the U.S.). <strong>The</strong>y state that “<strong>in</strong>the U.S., a professional is someone who […] has acquired a certa<strong>in</strong> expertise [which] isofficially acknowledged through certification and licensure […],” whereas <strong>in</strong> Malta, “the notionof professional is much looser […].” In India, “‘Professionalism’ is not a common word and tothe orthodox or older generation it connotes a lack of love for the job […]. Professionalism hasnoth<strong>in</strong>g to do with the level of one’s expertise” (p. 7). Consequently, the notion of ‘competence’as specified <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Program</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong> (see Jo<strong>in</strong>t Committee, 1994, p. 31) is not aprerequisite for an evaluator’s credibility across all cultures. <strong>The</strong> characteristics that causeclients to judge the professional evaluator as competent and trustworthy differ across cultures.For example, cross-cultural organizational psychology uses the pr<strong>in</strong>ciple of seniority to describedifferences <strong>in</strong> authority held by members of an organization (Berry et al., 1997, Vol. 3, p. 379).Accord<strong>in</strong>g to this pr<strong>in</strong>ciple, older people are per se attributed a higher degree of competence <strong>in</strong>certa<strong>in</strong> cultures, regardless of other factors also <strong>in</strong>fluenc<strong>in</strong>g competence, e.g., level of education(see Jang 2000, p. 26). <strong>The</strong> social status of a person (often positively correlated with age) alsoaffects the attribution of competence and trustworth<strong>in</strong>ess <strong>in</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> cultures, contrary to a moreachievement-oriented, <strong>in</strong>dividualistic approach to professional worth<strong>in</strong>ess. <strong>The</strong> latter is conveyed<strong>in</strong> the <strong>Standards</strong> when stat<strong>in</strong>g that "evaluators are credible to the extent that they exhibit thetra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, technical competence, substantive knowledge, experience, <strong>in</strong>tegrity, public relationsskills, and other characteristics considered necessary by clients […]" (Jo<strong>in</strong>t Committee, 1994, p.31). For example, Jang (2000, p. 11) notes that the well-known “name” of the evaluator is thebasis for be<strong>in</strong>g considered competent by South Korean clients. As another example, an Indianevaluator (see Hendricks & Conner, 1995, p. 83) describes his culture as one <strong>in</strong> which“personalized relationships and connections matter more than public <strong>in</strong>terest,” so that “a nexus

Cross-Cultural Transferability of the <strong>Program</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong> 15develops where evaluation is a means to bestow favors to each other irrespective of their levelsof competence.”U3 Information Scope and Selection Information collected should be broadlyselected to address pert<strong>in</strong>ent questions about the program and be responsive to theneeds and <strong>in</strong>terest of clients and other specified stakeholders.Standard U3, Information Scope and Selection, mentions multiple stakeholders, "each ofwhom should have an opportunity to provide <strong>in</strong>put to the evaluation design and have a claim foraccess to the results" (Jo<strong>in</strong>t Committee, 1994, p. 37). As po<strong>in</strong>ted out before, compliance with thisStandard is not necessarily desirable <strong>in</strong> a hierarchically structured society. <strong>The</strong> client and theevaluator might not f<strong>in</strong>d it important to extend <strong>in</strong>volvement to other than the s<strong>in</strong>gle most<strong>in</strong>fluential stakeholder group because other groups may not or should not <strong>in</strong>fluence theevaluation process and results (see Jang, 2000, p. 10). In addition, group-orientation and loyaltytoward authorities may forbid certa<strong>in</strong> stakeholder groups to voice their op<strong>in</strong>ions, contrary to thedemocratic approach generally evident <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Standards</strong> (Jo<strong>in</strong>t Committee, 1994). Also, as Jangobserves, “Koreans […] are not as experienced as Americans <strong>in</strong> express<strong>in</strong>g their personalop<strong>in</strong>ions” (2000, p. 18). <strong>The</strong> author attributes this phenomenon to “the cultural norm of<strong>in</strong>direction” (p. 18). In addition, there is a high tendency to perceive group consensus (falsegroup consensus effect) <strong>in</strong> collectivist cultures which further limits the <strong>in</strong>formation scope of theevaluation <strong>in</strong> these cultures (see Berry et al., 1997, Vol. 3, chapter 1, p. 58; Jang, 2000, p. 18, foran example from South Korea). Contrary to <strong>in</strong>dividualistic societies (e.g., Australia) where<strong>in</strong>group members are expected to act as <strong>in</strong>dividuals even if it means go<strong>in</strong>g aga<strong>in</strong>st the <strong>in</strong>group, <strong>in</strong>collectivist cultures (e.g., Indonesia, see Noesjirwan, 1978) the members of the <strong>in</strong>group shouldadapt to the group, ameliorat<strong>in</strong>g its unity (see Berry et al., 1997, Vol. 3, p. 143).U4 Values Identification <strong>The</strong> perspectives, procedures, and rationaleused to <strong>in</strong>terpret the f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs should be carefully described, so that the bases forvalue judgments are clear.Standard U4, Values Identification, is an example of a culturally sensitive Standard. Itcalls for the acknowledgment and description of contextually different value bases for<strong>in</strong>terpretation of obta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong>formation. "Value is the root term <strong>in</strong> evaluation; and valu<strong>in</strong>g […] isthe fundamental task <strong>in</strong> evaluations" (Jo<strong>in</strong>t Committee, 1994, p. 43). Values differ across<strong>in</strong>dividuals as well as across cultures (see above); therefore "it seems doubtful that any particularprescription for arriv<strong>in</strong>g at value judgments is consistently the best <strong>in</strong> all evaluative contexts"(Jo<strong>in</strong>t Committee, 1994, p. 43).

16 Sandy TautU5 Report Clarity <strong>Evaluation</strong> reports should clearly describe the program be<strong>in</strong>gevaluated, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g its context, and the purposes, procedures, and f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs of theevaluation, so that essential <strong>in</strong>formation is provided and easily understood.<strong>The</strong> fifth Utility Standard U5, Report Clarity, generally seems culturally universal but theconcept of clarity touches upon a cross-culturally relevant communication style issue. <strong>The</strong>Standard states that “[…] clarity refers to explicit and unencumbered narrative, illustrations, anddescriptions” (Jo<strong>in</strong>t Committee, 1994, p. 49). This might be contra<strong>in</strong>dicated <strong>in</strong> some cultureswhere <strong>in</strong>direct communication is the socially accepted way to exchange ideas and to makestatements. Barnlund (1975) contends that “the greater the cultural homogeneity [collectivism],the greater the mean<strong>in</strong>g conveyed <strong>in</strong> a s<strong>in</strong>gle word, the more that can be implied rather thanstated” (<strong>in</strong>: Berry et al., 1997, Vol. 3, p. 141). Jang (2000, p. 22) notes that <strong>in</strong> South Korea,public argumentation is “actively shunned because engag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> it means to stand out, risk publicdisagreement, and lose favor […].” In addition, context <strong>in</strong>formation will have a different impacton the <strong>in</strong>terpretations of given <strong>in</strong>formation. In collectivist cultures, the greater <strong>in</strong>terdependenceorients people toward greater sensitivity to context <strong>in</strong>formation and more mean<strong>in</strong>g is drawn fromit. In contrast, <strong>in</strong>dividualistic cultures, which are regarded as low-context cultures, place a greateremphasis on dispositional attributions (Berry et al., 1997, Vol. 3, chapter 1, p. 26).U6 Report Timel<strong>in</strong>ess and Dissem<strong>in</strong>ation Significant <strong>in</strong>terim f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs andevaluation reports should be dissem<strong>in</strong>ated to <strong>in</strong>tended users, so that they can be used<strong>in</strong> a timely fashion.Standard U6, Report Timel<strong>in</strong>ess and Dissem<strong>in</strong>ation, calls for report dissem<strong>in</strong>ation to “all<strong>in</strong>tended users” (Jo<strong>in</strong>t Committee, 1994, p. 53). Reach<strong>in</strong>g all stakeholders is not a goal if theclient expects absolute authority over the evaluation and sole reception of evaluation f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs.Jang (2000, p. 24f) argues that <strong>in</strong> South Korea, the responsibility of the evaluator is limited to“report<strong>in</strong>g to the top client” and that the top client decides about “the extent to which evaluationresults are shared.” Consequently, the practice of “fail<strong>in</strong>g to recognize stakeholders who do nothave spokespersons” (Jo<strong>in</strong>t Committee, 1994, p. 55, labeled as a Common Error) might beacceptable conduct <strong>in</strong> nonegalitarian cultures. Another culturally vary<strong>in</strong>g concept is that oftimel<strong>in</strong>ess. It is not a universal value and might therefore be excluded as part of proper conductfor evaluators <strong>in</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> cultures. For example, “Africans have different concept of time thanWestern audiences” (Russon & Patel, 1999, p. 6; also see Jang, 2000, p. 25; Smith et al., 1994, p.11).

Cross-Cultural Transferability of the <strong>Program</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong> 17U7 <strong>Evaluation</strong> Impact<strong>Evaluation</strong>s should be planned, conducted, andreported <strong>in</strong> ways that encourage follow-through by stakeholders, so that thelikelihood that the evaluation will be used is <strong>in</strong>creased.Regard<strong>in</strong>g Standard U7, <strong>Evaluation</strong> Impact, it is important to stress that the evaluatorshould encourage follow-through by stakeholders/clients <strong>in</strong> any culture–as long as hierarchicaland collectivist constra<strong>in</strong>ts do not prevent the evaluator from play<strong>in</strong>g such a role. For example,Jang (2000, p. 25) states that evaluators <strong>in</strong> South Korea should not “take responsibility for[enhanc<strong>in</strong>g] the use of the evaluation results”; this is solely the clients’ bus<strong>in</strong>ess. Lewy (1984, p.377) reports about Israel that “utilization of study results are mediated through an academic filteroperated by the chief scientist” who serves as a mediator between academic community andeducational adm<strong>in</strong>istration. <strong>The</strong>refore, Israeli evaluators will not be active <strong>in</strong> promot<strong>in</strong>g followthroughto the degree demanded by Standard U7.Feasibility <strong>Standards</strong>F1 Practical Procedures <strong>The</strong> evaluation procedures should be practical,to keep disruption to a m<strong>in</strong>imum while needed <strong>in</strong>formation is obta<strong>in</strong>ed.F2 Political Viability<strong>The</strong> evaluation should be planned andconducted with anticipation of the different positions of various <strong>in</strong>terest groups, sothat their cooperation may be obta<strong>in</strong>ed, and so that possible attempts by any of thesegroups to curtail evaluation operations or to bias or misapply the results can beaverted or counteracted.F3 Cost Effectiveness<strong>The</strong> evaluation should be efficient and produce<strong>in</strong>formation of sufficient value, so that the resources expended can be justified.In general, the Feasibility <strong>Standards</strong> seem more culturally universal than the Utility<strong>Standards</strong>. For example, <strong>Standards</strong> F1, Practical Procedures, and F3, Cost Effectiveness, seemculturally universal. However, F2, Political Viability, displays an egalitarian approach topolitical viability when it demands “[…] fair and equitable acknowledgment of the pressures andactions applied by various <strong>in</strong>terest groups with a stake <strong>in</strong> the evaluation” (Jo<strong>in</strong>t Committee,1994, p. 71). See U1 for further elaboration on the Stakeholder concept. Contrary to the<strong>Standards</strong>’ recommendation to avoid “giv<strong>in</strong>g the appearance -by attend<strong>in</strong>g to one stakeholdergroup more than another- that the evaluation is biased <strong>in</strong> favor of one group” (Jo<strong>in</strong>t Committee,

18 Sandy Taut1994, p. 72), <strong>in</strong> hierarchical cultures it might be crucial for a successful evaluation to attend toone (the most powerful, not necessarily the most important) stakeholder group more thananother. Generally, <strong>in</strong> more conservative (as opposed to autonomous) cultures, it is desirable torefra<strong>in</strong> from actions that might disrupt the solidarity of the group or traditional order (seeSchwartz 1994a, <strong>in</strong>: Berry et al., 1997, Vol. 3, p. 99). In these cultures, political <strong>in</strong>fluences arelikely to be stronger than <strong>in</strong> more autonomous societies like the United States where people seekto express their op<strong>in</strong>ions (see Jang, 2000, p. 10, for South Korean example). In India, forexample, accord<strong>in</strong>g to Smith et al. (1994, p. 3), “the quality of one’s evaluation work is morelikely to be judged on political than on technical or professional grounds.”Propriety <strong>Standards</strong>Miller and colleagues (1990, <strong>in</strong>: Berry et al., 1997, Vol. 3, p. 24) argue that “[…]conceptions of morality vary across cultures: A justice-based notion of morality that emphasizesautonomy of the <strong>in</strong>dividual and <strong>in</strong>dividual rights […] is found predom<strong>in</strong>antly <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividualisticcultural contexts.” This notion of morality (or propriety) relies upon impartial rules andstandards that are equally applicable to everybody. In contrast, <strong>in</strong> collectivist cultures “[…]morality constitutes a social practice that should be understood <strong>in</strong> terms of a duty-based<strong>in</strong>terpersonal code.” Lewy (1984, p. 379) also po<strong>in</strong>ts out the contextual dependency of ethicalcategories. Stufflebeam (1986, p. 4) notes that the Propriety <strong>Standards</strong> are “particularlyAmerican.” Russon & Patel (1999, p. 8) quote their African focus group participants consent<strong>in</strong>gthat the Propriety <strong>Standards</strong> portray “the greatest challenges” for transferability.<strong>The</strong>re is also a close connection between the Propriety <strong>Standards</strong> and the Hierarchy-Egalitarianism cultural dimension; egalitarian cultures stress the moral equality of <strong>in</strong>dividuals(Schwartz 1994a, <strong>in</strong>: Berry et al., 1997, Vol. 3, p. 63) while hierarchical societies emphasize thelegitimacy of <strong>in</strong>equality of <strong>in</strong>dividuals and groups. Jang (2000, p. 24) notes that <strong>in</strong>collectivist/hierarchical societies, ethical problems (as seen through Western eyes) might be“rationalized as be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the group’s best <strong>in</strong>terest.” In addition, there are high-context cultureswhich stress situational (context) <strong>in</strong>formation when judg<strong>in</strong>g behavior. In contrast, low-contextcultures, like the United States, refer more often to dispositional <strong>in</strong>formation, based on theassumption that traits have generality over time and situations (see Berry et al., 1997, Vol. 3, p.63). For all the reasons mentioned above, it generally seems difficult to transfer the Propriety<strong>Standards</strong> to collectivist/hierarchical/high-context cultures.P1 Service Orientation<strong>Evaluation</strong>s should be designed to assistorganizations to address and effectively serve the needs of the full range of targetedparticipants.Specifically, Standard P1, Service Orientation, calls for serv<strong>in</strong>g “program participants,community, and society” (Jo<strong>in</strong>t Committee, 1994, p. 83). In societies where there are largedifferences between <strong>in</strong>dividual/group status and goals (and where these differences areconsidered legitimate), this range of service delivery seems to be out of reach for the evaluator.Consumer rights, mirror<strong>in</strong>g service orientation and reflected by legislation, also vary across

Cross-Cultural Transferability of the <strong>Program</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong> 19cultures. North America is especially known all over the world for its service orientation.However, Standard P1 can be considered a universal goal for evaluators, even if not common <strong>in</strong>many cultures yet.P2 Formal AgreementsObligations of the formal parties to anevaluation (what is to be done, how, by whom, when) should be agreed to <strong>in</strong> writ<strong>in</strong>g,so that these parties are obligated to adhere to all conditions of the agreement orformally to renegotiate it.Smith et al. (1994, p. 10) po<strong>in</strong>t out the cultural differences <strong>in</strong> the way agreements arehandled. Formal agreements, especially as elaborated by Standard P2, Formal Agreements, arenot common practice <strong>in</strong> many cultures. For example, <strong>in</strong> India the power of formal agreements ismore limited than <strong>in</strong> the United States (see Smith et al., 1994, p. 10). Likewise, Jang (2000, p.18) observes that, for South Korea, memorandums and contracts <strong>in</strong> bus<strong>in</strong>ess sett<strong>in</strong>gs are lesscommon than <strong>in</strong> Western cultures. A contract might actually deteriorate the client-evaluatorrelationship because the client could perceive it as a sign of distrust toward him. This practicemight also be connected to communication style issues, i.e., the preference for <strong>in</strong>directcommunication might co<strong>in</strong>cide with a preference for <strong>in</strong>formal agreements.P3 Rights of Human Subjects<strong>Evaluation</strong>s should be designed andconducted to respect and protect the rights and welfare of human subjects.Standard P3, Rights of Human Subjects, is clearly based on U.S.-American legislation.As Chapman & Boothroyd (1988, p. 41) po<strong>in</strong>t out, American human rights laws “would neverpermit many practices <strong>in</strong> the United States that are common <strong>in</strong> evaluation studies <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>gcountries.” Smith et al. (1994, p. 11) also mention cross-culturally different ideas of what harms<strong>in</strong>dividual rights. For example, <strong>in</strong> Malta and India, reputation and mental health “are notpossessed by the <strong>in</strong>dividual <strong>in</strong> the U.S. sense.” Differences <strong>in</strong> human rights legislation are alsonoted by Hendricks & Conner (1995, p. 85). African evaluators noted <strong>in</strong> a discussion of thisStandard’s transferability that, contrary to many Western cultures, <strong>in</strong> Africa “the rights of the<strong>in</strong>dividual are perhaps more often considered subord<strong>in</strong>ate to the greater good of the group” (p.9).P4 Human InteractionsEvaluators should respect human dignity andworth <strong>in</strong> their <strong>in</strong>teractions with other persons associated with an evaluation, so thatparticipants are not threatened or harmed.Standard P4, Human Interactions, states cross-culturally relevant goals for evaluatorsalthough the actual professional behavior might differ considerably between different culturalsett<strong>in</strong>gs, due to vary<strong>in</strong>g desirable <strong>in</strong>terpersonal <strong>in</strong>teraction patterns (for examples toward eldersand high status persons, see Smith et al., 1994, p. 11).

20 Sandy TautP5 Complete and Fair Assessment <strong>The</strong> evaluation should be complete and fair <strong>in</strong> itsexam<strong>in</strong>ation and record<strong>in</strong>g of strengths and weaknesses of the program be<strong>in</strong>gevaluated, so that strengths can be built upon and problem areas addressed.Standard P5, Complete and Fair Assessment, exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g a program to f<strong>in</strong>d both strengthsand weaknesses, seems a goal for evaluators everywhere, despite multiple factors that might get<strong>in</strong> the way of this Standard, for example, pressures exerted by powerful stakeholders to stresseither strengths or weaknesses. <strong>The</strong>se pressures could be said to have more impact on evaluators<strong>in</strong> hierarchical and collectivist societies (also see analysis of Standard P7,‘Conflict of Interest’).P6 Disclosure of F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>The</strong> formal parties to an evaluation should ensure thatthe full set of evaluation f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs along with pert<strong>in</strong>ent limitations are made accessibleto the persons affected by the evaluation, and any others with expressed legal rights toreceive the results.Standard P6, Disclosure of F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs, displays the right to know which is legally grantedto United States citizens as part of the Bill of Rights. As an example of how values provideultimate standards, Peoples & Bailey (1997, p. 28) mention “the American emphasis on certa<strong>in</strong>rights of <strong>in</strong>dividuals as embodied <strong>in</strong> the Bill of Rights <strong>in</strong> the Constitution […] Freedom of thepress, of speech, and of religion are ultimate standards […].” In cultures other than the UnitedStates, these issues do not play such a vital role <strong>in</strong> an <strong>in</strong>dividual’s rights (see Beywl, 1996). Forexample, Hendricks & Conner (1995, p. 85) po<strong>in</strong>t out that Australia has a Freedom ofInformation Act but “it would be difficult (even under this act) to allow all relevant stakeholdersto have access to evaluative <strong>in</strong>formation, and …actively dissem<strong>in</strong>ate that <strong>in</strong>formation tostakeholders.” In addition, the “code of directness, openness, and completeness” (Jo<strong>in</strong>tCommittee, 1994, p. 109) might not be <strong>in</strong> accordance with the preference (and superiority) of<strong>in</strong>direct communication and the existence of hierarchical structures <strong>in</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> cultures. Jang(2000, p. 15) states that <strong>in</strong> South Korea, “the task of ‘fully’ <strong>in</strong>form<strong>in</strong>g research subjects who areunfamiliar with the purposes and procedures of the study is not the first concern.” Likewise,absence of such disclosure might not, as claimed <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Standards</strong> (p. 109), threaten theevaluation’s credibility. To the contrary, the absence of disclosure may preserve the evaluation'scredibility <strong>in</strong> some cultures. Smith et al. (1993, p. 10) offer an example of the acceptable absenceof disclosure when they refer to both Maltese and Indian cultures. For these cultures, thepossibility of “plac<strong>in</strong>g someone <strong>in</strong> jeopardy” (e.g., by negative evaluation f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs) is nevercommunicated <strong>in</strong> writ<strong>in</strong>g, thus limit<strong>in</strong>g the disclosure of f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs.

Cross-Cultural Transferability of the <strong>Program</strong> <strong>Evaluation</strong> <strong>Standards</strong> 21P7 Conflict of InterestConflict of <strong>in</strong>terest should be dealt with openlyand honestly, so that it does not compromise the evaluation processes and results.Standard P7, Conflict of Interest, is another Standard reflect<strong>in</strong>g North American values.<strong>The</strong>re are different cultural standards for deal<strong>in</strong>g with conflicts. Group-orientation <strong>in</strong> collectivistcultures results <strong>in</strong> conflict avoidance or non-adversarial conflict resolution with<strong>in</strong> groups (seeBerry et al., 1997, Vol. 3, chapter 1, p. 26). In those cultures, it might be counterproductive toopenly address an exist<strong>in</strong>g conflict. In some cultures, direct communication is generally avoided(see Jang, 2000, p. 18). Another cross-culturally relevant problem with this Standard is thehigher <strong>in</strong>terdependency of people <strong>in</strong> collectivist societies. Personal friendships or professionalrelationships play a much more crucial role <strong>in</strong> these cultures than <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividualistic societies suchas the U.S. As Jang (2000, p. 12) describes South Korean culture, “professionalism is def<strong>in</strong>edma<strong>in</strong>ly by an <strong>in</strong>dividual’s loyalty toward the group he or she serves.” In addition to the priorityof group <strong>in</strong>terest, Jang mentions the great impact of authority figures on op<strong>in</strong>ion formation (p.22). Accord<strong>in</strong>g to Smith et al. (1993, p. 10), Indian evaluators are “specifically chosen for apo<strong>in</strong>t of view consistent with the official position” and this would not be considered a conflict of<strong>in</strong>terest situation there. Standard P7 can therefore be considered unsuitable <strong>in</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> culturalcontexts.P8 Fiscal Responsibility <strong>The</strong> evaluator’s allocation and expenditure ofresources should reflect sound accountability procedures and otherwise be prudentand ethically responsible, so that expenditures are accounted for and appropriate.F<strong>in</strong>ally, Standard P8, Fiscal Responsibility, is seen as cross-culturally applicable.Accuracy <strong>Standards</strong>Across cultures, different degrees of importance are allocated to accuracy as part of anevaluation (see Nevo, 1984, p. 385 on the high priority of accuracy <strong>in</strong> Israeli evaluations). Databasedjudgements might be less credible than personal op<strong>in</strong>ions from authorities <strong>in</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> highhierarchycultures (e.g., not meet<strong>in</strong>g the notion of accuracy that the <strong>Standards</strong> display. <strong>The</strong>concept of ‘Uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty Avoidance’ might provide some cross-cultural psychologicalexplanation for differences <strong>in</strong> importance of reliability. For example, Hofstede (1980) talksabout Uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty Avoidance <strong>in</strong> terms of how comfortable people are with uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty orambiguity <strong>in</strong> their lives, or else, how much they value security and reliability. Jang (2000, p. 16)notes that although South Koreans “believe western systematic methodology is very useful <strong>in</strong>analyz<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formation” (she also mentions the considerable U.S. <strong>in</strong>fluence with<strong>in</strong> the academiccommunity <strong>in</strong> South Korea), it is necessary to <strong>in</strong>volve South Korean staff to ensure receiv<strong>in</strong>greliable, valid data as the <strong>Standards</strong> call for. This quote implies that there is a “western”methodology that <strong>in</strong>variably needs adaptation when applied <strong>in</strong> non-western contexts (see Jang,2000, for advice on South Korea).