2010/2011

Estonian Human Development Report - Eesti Koostöö Kogu

Estonian Human Development Report - Eesti Koostöö Kogu

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

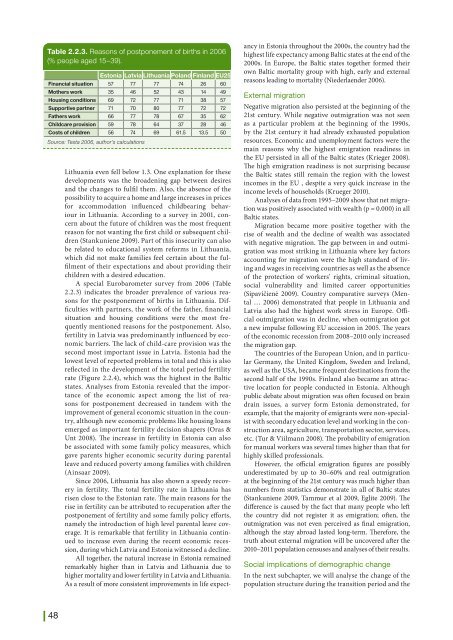

Table 2.2.3. Reasons of postponement of births in 2006<br />

(% people aged 15–39).<br />

Estonia Latvia Lithuania Poland Finland EU25<br />

Financial situation 57 77 77 74 26 60<br />

Mothers work 35 46 52 43 14 49<br />

Housing conditions 69 72 77 71 38 57<br />

Supportive partner 71 70 80 77 72 72<br />

Fathers work 66 77 78 67 35 62<br />

Childcare provision 59 78 64 37 28 46<br />

Costs of children 56 74 69 61.5 13.5 50<br />

Source: Testa 2006, author’s calculations<br />

Lithuania even fell below 1.3. One explanation for these<br />

developments was the broadening gap between desires<br />

and the changes to fulfil them. Also, the absence of the<br />

possibility to acquire a home and large increases in prices<br />

for accommodation influenced childbearing behaviour<br />

in Lithuania. According to a survey in 2001, concern<br />

about the future of children was the most frequent<br />

reason for not wanting the first child or subsequent children<br />

(Stankuniene 2009). Part of this insecurity can also<br />

be related to educational system reforms in Lithuania,<br />

which did not make families feel certain about the fulfilment<br />

of their expectations and about providing their<br />

children with a desired education.<br />

A special Eurobarometer survey from 2006 (Table<br />

2.2.3) indicates the broader prevalence of various reasons<br />

for the postponement of births in Lithuania. Difficulties<br />

with partners, the work of the father, financial<br />

situation and housing conditions were the most frequently<br />

mentioned reasons for the postponement. Also,<br />

fertility in Latvia was predominantly influenced by economic<br />

barriers. The lack of child-care provision was the<br />

second most important issue in Latvia. Estonia had the<br />

lowest level of reported problems in total and this is also<br />

reflected in the development of the total period fertility<br />

rate (Figure 2.2.4), which was the highest in the Baltic<br />

states. Analyses from Estonia revealed that the importance<br />

of the economic aspect among the list of reasons<br />

for postponement decreased in tandem with the<br />

improvement of general economic situation in the country,<br />

although new economic problems like housing loans<br />

emerged as important fertility decision shapers (Oras &<br />

Unt 2008). The increase in fertility in Estonia can also<br />

be associated with some family policy measures, which<br />

gave parents higher economic security during parental<br />

leave and reduced poverty among families with children<br />

(Ainsaar 2009).<br />

Since 2006, Lithuania has also shown a speedy recovery<br />

in fertility. The total fertility rate in Lithuania has<br />

risen close to the Estonian rate. The main reasons for the<br />

rise in fertility can be attributed to recuperation after the<br />

postponement of fertility and some family policy efforts,<br />

namely the introduction of high level parental leave coverage.<br />

It is remarkable that fertility in Lithuania continued<br />

to increase even during the recent economic recession,<br />

during which Latvia and Estonia witnessed a decline.<br />

All together, the natural increase in Estonia remained<br />

remarkably higher than in Latvia and Lithuania due to<br />

higher mortality and lower fertility in Latvia and Lithuania.<br />

As a result of more consistent improvements in life expect-<br />

ancy in Estonia throughout the 2000s, the country had the<br />

highest life expectancy among Baltic states at the end of the<br />

2000s. In Europe, the Baltic states together formed their<br />

own Baltic mortality group with high, early and external<br />

reasons leading to mortality (Niederlaender 2006).<br />

External migration<br />

Negative migration also persisted at the beginning of the<br />

21st century. While negative outmigration was not seen<br />

as a particular problem at the beginning of the 1990s,<br />

by the 21st century it had already exhausted population<br />

resources. Economic and unemployment factors were the<br />

main reasons why the highest emigration readiness in<br />

the EU persisted in all of the Baltic states (Krieger 2008).<br />

The high emigration readiness is not surprising because<br />

the Baltic states still remain the region with the lowest<br />

incomes in the EU , despite a very quick increase in the<br />

income levels of households (Krueger <strong>2010</strong>).<br />

Analyses of data from 1995–2009 show that net migration<br />

was positively associated with wealth (p = 0.000) in all<br />

Baltic states.<br />

Migration became more positive together with the<br />

rise of wealth and the decline of wealth was associated<br />

with negative migration. The gap between in and outmigration<br />

was most striking in Lithuania where key factors<br />

accounting for migration were the high standard of living<br />

and wages in receiving countries as well as the absence<br />

of the protection of workers’ rights, criminal situation,<br />

social vulnerability and limited career opportunities<br />

(Sipavičienė 2009). Country comparative surveys (Mental<br />

… 2006) demonstrated that people in Lithuania and<br />

Latvia also had the highest work stress in Europe. Official<br />

outmigration was in decline, when outmigration got<br />

a new impulse following EU accession in 2005. The years<br />

of the economic recession from 2008–<strong>2010</strong> only increased<br />

the migration gap.<br />

The countries of the European Union, and in particular<br />

Germany, the United Kingdom, Sweden and Ireland,<br />

as well as the USA, became frequent destinations from the<br />

second half of the 1990s. Finland also became an attractive<br />

location for people conducted in Estonia. Although<br />

public debate about migration was often focused on brain<br />

drain issues, a survey form Estonia demonstrated, for<br />

example, that the majority of emigrants were non-specialist<br />

with secondary education level and working in the construction<br />

area, agriculture, transportation sector, services,<br />

etc. (Tur & Viilmann 2008). The probability of emigration<br />

for manual workers was several times higher than that for<br />

highly skilled professionals.<br />

However, the official emigration figures are possibly<br />

underestimated by up to 30–60% and real outmigration<br />

at the beginning of the 21st century was much higher than<br />

numbers from statistics demonstrate in all of Baltic states<br />

(Stankuniene 2009, Tammur et al 2009, Eglite 2009). The<br />

difference is caused by the fact that many people who left<br />

the country did not register it as emigration; often, the<br />

outmigration was not even perceived as final emigration,<br />

although the stay abroad lasted long-term. Therefore, the<br />

truth about external migration will be uncovered after the<br />

<strong>2010</strong>–<strong>2011</strong> population censuses and analyses of their results.<br />

Social implications of demographic change<br />

In the next subchapter, we will analyse the change of the<br />

population structure during the transition period and the<br />

| 48