GETTING THE WORD OUT

New_Scientist_2_April_2016@englishmagazines

New_Scientist_2_April_2016@englishmagazines

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

FROZEN STIFF<br />

Did interstellar cloud<br />

kill off the dinosaurs?<br />

IMPRECISION ENGINEERING<br />

To make computers better,<br />

try making them worse<br />

YOU SWINE!<br />

Problem porkers wreak<br />

havoc worldwide<br />

WEEKLY April 2 -8, 2016<br />

MINIMAL LIFE We’ve made the tiniest genome that works<br />

To explain our cosmic backyard,<br />

we need to break gravity<br />

No3067 US$5.95 CAN$5.95<br />

1 3<br />

0 70989 30690 5<br />

Science and technology news<br />

www.newscientist.com<br />

US jobs in science<br />

<strong>GETTING</strong> <strong>THE</strong> <strong>WORD</strong> <strong>OUT</strong> Stuttering starts deep in the brain

CONTENTS<br />

Volume 230 No 3067<br />

This issue online<br />

newscientist.com/issue/3067<br />

News<br />

6<br />

Unlocking the<br />

essence of life<br />

We’ve made the tiniest<br />

genome that works<br />

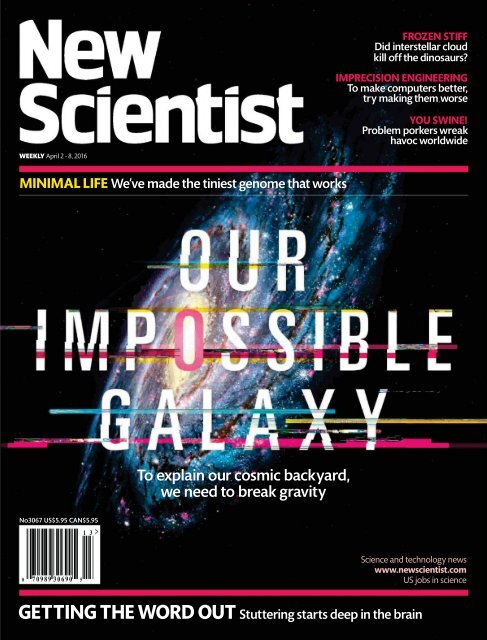

On the cover<br />

30<br />

Our impossible<br />

galaxy<br />

To explain our cosmic<br />

backyard, we need to<br />

break gravity<br />

Cover image<br />

Lynette Cook/Science Photo Library<br />

Features<br />

34<br />

Getting the<br />

word out<br />

Stuttering starts<br />

deep in the brain<br />

SERGE PICARD/AGENCE VU/CAMERAPRESS TOM DEERINCK & MARK ELLISMAN/NCMIR/UCSD<br />

8 Frozen stiff<br />

Did an interstellar cloud<br />

kill off the dinosaurs?<br />

36 Imprecision engineering<br />

To make computers<br />

better, make them worse<br />

40 You swine!<br />

Porkers wreak havoc<br />

6 Minimal life<br />

Tiniest working genome<br />

34 Getting the word out<br />

Stuttering and the brain<br />

Coming next week…<br />

On the road<br />

Is migration really a crisis?<br />

Black holes unmasked<br />

Frozen universe reveals their secrets<br />

Leaders<br />

3 Exploring the essentials of life isn’t about<br />

playing god. To err should be inhuman<br />

News<br />

4 UPFRONT<br />

Could bomb sensors stop another Brussels?<br />

Fast Antarctic ice melt could see catastrophic<br />

sea rise. Gecko Grippers head to space<br />

6 THIS WEEK<br />

Did a cosmic cloud kill the dinosaurs? Mars<br />

had a short-lived ocean. Prairie dog serial<br />

killers. The twins who felt fear for the first<br />

time. Lock up CO 2 in building materials. How<br />

brain-zapping works. Bright spots on Ceres.<br />

Stacking oranges in 24 dimensions<br />

15 IN BRIEF<br />

Migrating birds stay in UK for longer. Cats<br />

give us rage. Ghost galaxies. Exercise for a<br />

young brain. Unlocking ancient scroll library<br />

Technology<br />

18 Get immersed as first virtual reality games<br />

go on sale. Inside the factory of the future<br />

Aperture<br />

22 What the Zika virus looks like – probably<br />

Opinion<br />

24 Hinkley’s point Paul Ekins urges rethinking<br />

the world’s biggest nuclear power project<br />

24 US in Cuba Michael Clegg on a hopeful start<br />

25 INSIGHT Londoners’ toxic air nightmare<br />

28 Roborescue It’s time robots took their place<br />

in search and rescue, says Robin Murphy<br />

Features<br />

30 Our impossible galaxy (see above left)<br />

34 Getting the word out (see left)<br />

36 Imprecision engineering To make<br />

computers better, try making them worse<br />

40 You swine! Problem porkers wreak havoc<br />

worldwide<br />

CultureLab<br />

42 Animal crackers Pretending to be other<br />

creatures is an altogether human game<br />

43 A drug to make us good Hunting for<br />

morality in a neuroscientific mess<br />

Regulars<br />

52 LETTERS Theory proposes<br />

56 FEEDBACK When is a drug not a drug?<br />

57 <strong>THE</strong> LAST <strong>WORD</strong> Atomic bonds<br />

2 April 2016 | NewScientist | 1

LEADERS<br />

LOCATIONS<br />

USA<br />

50 Hampshire St, Floor 5,<br />

Cambridge, MA 02139<br />

Please direct telephone enquiries to<br />

our UK office +44 (0) 20 7611 1200<br />

UK<br />

110 High Holborn,<br />

London, WC1V 6EU<br />

Tel +44 (0) 20 7611 1200<br />

Fax +44 (0) 20 7611 1250<br />

Australia<br />

Tower 2, 475 Victoria Avenue,<br />

Chatswood, NSW 2067<br />

Tel +61 2 9422 8559<br />

Fax +61 2 9422 8552<br />

ELI MEIR KAPLAN/FOR <strong>THE</strong> WASHINGTON POST VIA GETTY<br />

SUBSCRIPTION SERVICE<br />

For our latest subscription offers, visit<br />

newscientist.com/subscribe<br />

Customer and subscription services are<br />

also available by:<br />

Telephone 1-888-822-3242<br />

Email subscribe@newscientist.com<br />

Web newscientist.com/subscribe<br />

Mail New Scientist, PO Box 3806,<br />

Chesterfield, MO 63006-9953 USA<br />

One year subscription (51 issues) $154<br />

CONTACTS<br />

Contact us<br />

newscientist.com/contact<br />

Who’s who<br />

newscientist.com/people<br />

General & media enquiries<br />

enquiries@newscientist.com<br />

Editorial<br />

Tel 781 734 8770<br />

news@newscientist.com<br />

features@newscientist.com<br />

opinion@newscientist.com<br />

Picture desk<br />

Tel +44 (0) 20 7611 1268<br />

Display advertising<br />

Tel 781 734 8770<br />

displaysales@newscientist.com<br />

Recruitment advertising<br />

Tel 781 734 8770<br />

nssales@newscientist.com<br />

Newsstand<br />

Tel 212 237 7987<br />

Distributed by Time/Warner Retail<br />

Sales and Marketing, 260 Cherry Hill<br />

Road, Parsippany, NJ 07054<br />

Syndication<br />

Tribune Content Agency<br />

Tel 800 637 4082<br />

© 2016 Reed Business<br />

Information Ltd, England.<br />

New Scientist ISSN 0262 4079 is<br />

published weekly except for the last<br />

week in December by Reed Business<br />

Information Ltd, England.<br />

New Scientist (Online) ISSN 2059 5387<br />

New Scientist at Reed Business<br />

Information, c/o Schnell Publishing Co.<br />

Inc., 225 Wyman Street, Waltham,<br />

MA 02451.<br />

Periodicals postage paid at<br />

Boston, MA and other mailing offices.<br />

Postmaster: Send address changes<br />

to New Scientist, PO Box 3806,<br />

Chesterfield, MO 63006-9953, USA.<br />

Registered at the Post Office as a<br />

newspaper and printed in USA by Fry<br />

Communications Inc, Mechanicsburg,<br />

PA 17055<br />

Bare necessities<br />

Exploring the essentials of life isn’t about playing God<br />

HAVE we found the essentials of<br />

life? A team in the US has reduced<br />

the number of genes in a modest<br />

bug called Mycoplasma mycoides<br />

by almost half, creating the tiniest<br />

genome that can support vital<br />

survival functions (see page 6).<br />

The new strain is called JVCIsyn3.0,<br />

the letters coming from<br />

the name of the J. Craig Venter<br />

Institute in La Jolla, California.<br />

The institute is named after the<br />

charismatic biotechnologist<br />

who is almost as well known for<br />

his swagger as for his scientific<br />

achievements. The first human<br />

genome to be fully sequenced<br />

was Venter’s own, and he has in<br />

the past drawn opprobrium for<br />

attempting to patent genes. His<br />

apparent grandiosity irks more<br />

buttoned-down colleagues.<br />

And his ambition prompts those<br />

averse to genetic engineering to<br />

invoke inchoate risks, frequently<br />

buttressed by the claim that it<br />

amounts to “playing God”. This<br />

time, Venter’s rhetoric has been<br />

reined in a little. The genome of<br />

JVCI-syn3.0, while put together<br />

on a computer and assembled by<br />

DNA sequencers, includes no new<br />

or artificial genes. If anything, its<br />

creation shows the limits of our<br />

power and depth of our ignorance:<br />

we have no idea what a third of the<br />

genes the team found actually do.<br />

But now we can start figuring<br />

out what the essentials of life<br />

really are. That will, Venter insists,<br />

invigorate synthetic biology,<br />

with benefits for all of us: he, and<br />

Toerrshouldbeinhuman<br />

NEURAL networks, like the ones<br />

grabbing headlines for winning<br />

boardgames or driving cars,<br />

depend on huge amounts of<br />

computing hardware. That in<br />

turn means a colossal amount<br />

of power: the next wave may<br />

consume millions of watts each.<br />

That’s one reason why some<br />

suggest we rethink what we want<br />

computers to be. Reducing the<br />

precision with which they analyse<br />

problems, and putting up with<br />

the odd“error”, can cut zeroes off<br />

their energy consumption (see<br />

page 36). And it has precedent in<br />

the human brain – an unrivalled<br />

piece of hardware using electrical<br />

fluctuations and requiring a<br />

million times less power than<br />

a computer.<br />

Introducing error will also make<br />

computers better at handling<br />

the real world. Neural networks,<br />

others, want to design organisms<br />

that can make biofuels, protein<br />

or vaccines more efficiently.<br />

Since Venter made his first<br />

synthetic cell in 2010, however,<br />

the ease of gene editing has<br />

exploded. This allows scientists to<br />

tweak genomes far more cheaply<br />

than building them from scratch.<br />

The CRISPR technique, which has<br />

itself generated much ethical<br />

controversy, might end up the<br />

more practical and widespread<br />

method. Either way, far from<br />

wilfully taking risks – playing<br />

God, if you really must – synthetic<br />

biologists are developing the<br />

expertise to address very human<br />

needs. Venter’s bullish approach<br />

has brought that a step closer.<br />

Let him swagger. ■<br />

loosely modelled on the brain,<br />

capture some of its problemsolving<br />

capacity. AlphaGo<br />

surprised opponents and<br />

designers alike with Go moves<br />

described by some as “intuitive”.<br />

Computers that play Go,<br />

understand human language and<br />

behaviour, spot patterns across<br />

databases of genetic information<br />

or forecast economic and climate<br />

trends do not deal in absolutes.<br />

It is their rough guesses that will<br />

bring us closest to comprehensive<br />

artificial intelligence. ■<br />

2 April 2016 | NewScientist | 3

UPFRONT<br />

ADAM BERRY/GETTY<br />

Satellite lost<br />

JUNKED? Hitomi, a Japanese<br />

astronomy satellite, seems to be<br />

tumbling through space, and may<br />

have broken up. It was due to<br />

come online on 26 March, but<br />

failed to communicate with Earth.<br />

A tweet by the US Joint Space<br />

Operations Center reported five<br />

pieces of debris around the<br />

satellite shortly afterwards.<br />

All may not be lost. The Japan<br />

Aerospace Exploration Agency<br />

heard a brief burst of signal from<br />

the craft, and video taken from<br />

the ground suggests it is falling<br />

through space.<br />

“That indicates the sat was<br />

at that point alive, just unable<br />

to point its antenna at Earth,”<br />

says Jonathan McDowell at the<br />

“If we never hear from<br />

the satellite again,<br />

I would be devastated<br />

but not surprised”<br />

Can we sniff out bombs?<br />

LAST week, terrorists walked into scanned by an array of sensors as<br />

Brussels’ Zaventem airport and<br />

they walk through the tunnel to<br />

detonated bomb-laden luggage get into airports or train stations.<br />

in the check-in area. They also<br />

The Lincoln Laboratory at<br />

bombed a subway station.<br />

the Massachusetts Institute of<br />

As New Scientist went to press,<br />

Technology has a different approach.<br />

35 people had been killed and<br />

A team there has turned to lasers<br />

hundreds wounded.<br />

to “sniff” explosives from a distance.<br />

Can we stop attacks like this?<br />

The lab says it can scan spaces like<br />

Airport security focuses on keeping check-in areas from 100 metres<br />

explosives off planes. Stopping<br />

away by sweeping them with<br />

bombs detonating in crowded<br />

lasers tuned to frequencies that<br />

check-in areas and transit terminals vaporise molecules found in<br />

is a bigger challenge. Security<br />

bombs. This material makes a tiny<br />

checkpoints work, but they cause sound as it vaporises, which is<br />

delays and create queues that can amplified and detected.<br />

also be a target. But there are new<br />

Lasers are also used in a device<br />

ways to scan people as they walk. called G-Scan, developed by Laser<br />

Cameron Ritchie, head of<br />

Detect Systems of Ramat Gan in Israel.<br />

technology at the US-based security This fires a green laser at a target then<br />

firm Morpho, is working on a “tunnel uses Raman spectroscopy to<br />

of truth”. Passengers would be<br />

“fingerprint” the molecules that<br />

scatter light back. It can identify<br />

anything visible, including bottle<br />

contents or surface smears.<br />

Detecting explosive material from<br />

a distance would enable security<br />

services to track down bomb-making<br />

supplies – not just finished weapons.<br />

By scanning for telltale chemicals on<br />

people’s bodies and clothes as they<br />

move around cities, security services<br />

may be able to catch suspects before<br />

they have built their device.<br />

One concern is that such sensitive<br />

detectors may trigger many false<br />

alarms. There is also the question<br />

of whether airport and train security<br />

staff can respond to a positive signal<br />

quickly and effectively enough to<br />

neutralise a threat, says Brian<br />

Jenkins, a security researcher at the<br />

Rand Corporation. “You can’t just yell,<br />

‘hey you with the bomb’.”<br />

Harvard-Smithsonian Center for<br />

Astrophysics. He says it might be<br />

possible to talk to Hitomi and<br />

stop it tumbling. “But if you told<br />

me we were never going to hear<br />

from the sat again, I would be<br />

devastated but not surprised,”<br />

he says.<br />

Hitomi’s mission is to<br />

observe the universe in X-rays,<br />

investigating matters such as<br />

the birth of black holes and the<br />

origins of cosmic rays.<br />

Space geckos<br />

IN A few years, the exterior of the<br />

International Space Station could<br />

be crawling with geckos. It’s not<br />

an alien invasion, or the plot of a<br />

low-budget sci-fi movie. The<br />

robotic geckos could follow from<br />

an experiment NASA launched to<br />

the International Space Station<br />

last week aboard an uncrewed<br />

Cygnus spacecraft.<br />

The Gecko Gripper devices use<br />

tiny artificial hairs that replicate<br />

the ones geckos use to climb walls.<br />

They are designed to help<br />

4 | NewScientist | 2 April 2016

For new stories every day, visit newscientist.com/news<br />

60 SECONDS<br />

astronauts keep track of objects in<br />

zero gravity, and enable robots to<br />

crawl around a spacecraft to<br />

inspect and repair it.<br />

The bots have already been<br />

tested on parabolic aircraft flights,<br />

where they grabbed and<br />

manipulated 10-kilogram and<br />

100-kg objects during 20-second<br />

periods of microgravity. On the<br />

ISS trip, astronauts will test the<br />

system by attaching five devices<br />

in a range of sizes to 30 surfaces<br />

inside the space station at<br />

different angles, to check how well<br />

they grip. The devices will be left<br />

in place for periods of time<br />

between two weeks and a year.<br />

HIV prevention<br />

COLIN MONTEATH/HEDGEHOG HOUSE/MINDEN<br />

Zika’s arrival traced<br />

ONE person carried the Zika virus<br />

to the Americas a full two years<br />

before its detection there last year.<br />

Brazil was the first country in<br />

the Americas to report Zika, in<br />

May 2015, and the virus has since<br />

infected hundreds of thousands<br />

of people in 33 countries. The<br />

virus is native to Africa but in the<br />

last 10 years it jumped to some of<br />

the islands of Micronesia and<br />

Polynesia in the Pacific.<br />

A genetic analysis suggests the<br />

virus in the Americas came from<br />

an individual infected in<br />

Polynesia, and that it arrived<br />

IT SAVES money and prolongs A MASSIVE rise in sea level is coming,<br />

lives, but who should pay – the UK and it will trigger climate chaos<br />

health service or local councils? around the world. That was the<br />

Trials around the world have message from a controversial recent<br />

shown that Truvada, an antiviral paper by climate scientist James<br />

drug, helps prevent uninfected, Hansen. It was slated by many for<br />

at-risk people from getting HIV. assuming – rather than showing –<br />

After 18 months of negotiations, that sea level could rise by between<br />

it looked certain that NHS England 1 and 5 metres by 2100.<br />

would foot the bill if Truvada was But now, just a week after being<br />

rolled out across England. Instead, formally published, it is being backed<br />

on 21 March NHS England<br />

up by another study. “He was<br />

announced it would mount a<br />

speculating on massive fresh water<br />

two-year, £2 million pilot study of discharge to the ocean that I don’t<br />

500 men at high risk of infection think anybody thought was possible<br />

to assess the efficacy and cost.<br />

before,” says Rob DeConto of the<br />

NHS England also backed away University of Massachusettsfrom<br />

funding the drug, saying Amherst. “Now we’re about to<br />

that the bill should be met by local publish a paper that says these rates<br />

authorities, which provide other of fresh water input are possible.”<br />

HIV services.<br />

“After 18 months, it’s galling to<br />

be told that,” says Sarah Radcliffe<br />

at the National AIDS Trust charity.<br />

She says there is abundant<br />

evidence that Truvada is effective<br />

and cuts healthcare costs.<br />

Teresa O’Neill of London<br />

Councils says the capital has the<br />

country’s highest rates of HIV so<br />

councils there would face a high<br />

bill. She points out that it costs<br />

£380,000 to treat an HIV-positive<br />

person for life, versus £4700 to<br />

supply Truvada for a year, so you’d<br />

have to take the drug for 80 years<br />

before it became more expensive. –Still there… for now–<br />

between May and December 2013.<br />

“One person with the infection<br />

was bitten by a mosquito and that<br />

chain of infection persisted,” says<br />

Oliver Pybus of the University of<br />

Oxford (Science, doi.org/bdrx).<br />

It isn’t surprising it took two<br />

“Zika in the Americas came<br />

from an individual infected<br />

in Polynesia, and it arrived<br />

in the second half of 2013”<br />

years for Zika’s presence to come<br />

to light. Its symptoms closely<br />

resemble those of dengue and<br />

chikungunya viruses, which were<br />

already circulating.<br />

Catastrophic Antarctic melting<br />

DeConto’s model includes factors<br />

that previous studies omitted. First,<br />

floating ice shelves around Antarctica<br />

will soon be exposed to above-zero<br />

summer air temperatures, speeding<br />

their melt, he says. Second, once the<br />

shelves are gone, the huge ice cliffs<br />

that remain will begin to collapse<br />

(Nature, DOI: 10.1038/nature17145).<br />

DeConto’s findings suggest that<br />

even if countries meet the pledges<br />

made as part of the Paris agreement,<br />

global sea level could still rise 1 metre<br />

by 2100. If emissions keep climbing it<br />

could go up more than 2 metres.<br />

“Today we’re measuring global sea<br />

level rise in millimetres per year,”<br />

DeConto says. “We’re talking about<br />

the potential for centimetres per year<br />

just from Antarctica.”<br />

Bleach bum<br />

It’s a white-out for the Great Barrier<br />

Reef. An aerial survey last week<br />

showed that at least 95 per cent of<br />

the reef’s northern 1000 kilometres<br />

has been severely bleached. It’s the<br />

worst case in history, says the<br />

National Coral Bleaching Taskforce,<br />

which carried out the survey.<br />

Bleaching is caused by high sea<br />

temperatures and can kill coral.<br />

Apple vs FBI<br />

The stand-off is over, for now. The<br />

FBI has successfully broken into the<br />

iPhone belonging to San Bernardino<br />

gunman Syed Rizwan Farook,<br />

bringing to a halt its legal battle with<br />

Apple. In court documents filed on<br />

Monday, the FBI said it no longer<br />

required Apple’s assistance to access<br />

files on the phone, although it hasn’t<br />

made public how it did it.<br />

Stroke protection<br />

Giving mice antibiotics can protect<br />

them from brain damage caused by<br />

stroke. Antibiotics change the makeup<br />

of the mice’s gut bacteria, which<br />

in turn alters the immune cells<br />

that travel to the brain and would<br />

normally cause inflammation. The<br />

treatment appears to reduce cell<br />

destruction by around 60 per cent<br />

(Nature Medicine, doi.org/bdrw).<br />

Green boom<br />

More than twice as much was<br />

spent on new capacity to generate<br />

electricity from renewables like<br />

solar and wind than on power<br />

stations that burn fossil fuels last<br />

year. China was responsible for twothirds<br />

of the renewables investment<br />

in the developing world, and 36 per<br />

cent of the global total.<br />

Permafrost pups<br />

Two puppies that lived 12,460 years<br />

ago have been discovered perfectly<br />

preserved in permafrost in the<br />

northern Russian region of Yakutia.<br />

Last week, one of them underwent<br />

an autopsy so that its organs can be<br />

compared with those of modern<br />

dogs and wolves.<br />

2 April 2016 | NewScientist | 5

THIS WEEK<br />

Smallest ever genome comes to life<br />

Humans built it, but we don’t know what a third of its genes actually do<br />

Andy Coghlan<br />

WE HAVE even further to<br />

go to understand life than we<br />

thought. In creating the latest<br />

landmark synthetic organism –<br />

the world’s first minimal<br />

genome – Craig Venter and his<br />

team have discovered that we<br />

don’t know the functions of<br />

almost a third of the genes<br />

that are vital for life.<br />

“Finding so many genes without<br />

a known function is unsettling,<br />

but it’s exciting because it’s left<br />

us with much still to learn,” says<br />

Alistair Elfick, a bioengineer at the<br />

University of Edinburgh, UK. “It’s<br />

like the ‘dark matter’ of biology.”<br />

Venter, founder of the J. Craig<br />

Venter Institute in La Jolla,<br />

California, has long hoped to<br />

unravel life’s essential toolkit.<br />

Now his team has created the<br />

first minimal genome – the tiniest<br />

possible stash of DNA capable of<br />

supporting life. With 473 genes,<br />

the new cell, JCVI-syn3.0, has at<br />

least 50 fewer genes than nature’s<br />

record-holder for the shortest<br />

genome in a self-sustaining living<br />

organism, Mycoplasma genitalium<br />

(Science, doi.org/bdrz).<br />

The feat builds on JCVI-syn1.0,<br />

LIFE FROM SCRATCH? NOT YET<br />

The design of the first synthetic<br />

minimal genome hints at new ways<br />

to build life. So can we do this from<br />

scratch? Not quite.<br />

For a start, the genome is<br />

based on a slimline version of<br />

one from a naturally occurring<br />

bacterium. The genes were not<br />

dreamed up by people, but<br />

had already evolved in nature.<br />

Also, to make the minimal genome,<br />

researchers didn’t create any new<br />

genes or biological functions,<br />

but simply dumped those not<br />

TOM DEERINCK & MARK ELLISMAN/NCMIR/UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT SAN DIEGO<br />

the first living bacterium reliant<br />

on a synthetic copy of an existing<br />

genome, unveiled by Venter in<br />

2010. That genome was designed<br />

in a computer, before assembly<br />

and insertion into cells.<br />

Since then, Venter and his<br />

colleagues, co-led by Clyde<br />

Hutchison, have been whittling<br />

essential for keeping the cell alive.<br />

Then there was the cell itself.<br />

Once the genome was designed<br />

from code on a computer, it had to<br />

be put inside a living cell stripped of<br />

its own, native genome. That cell also<br />

came from a living natural bacterium<br />

that had all the intricate cellular<br />

machinery already in place. And the<br />

process revealed we have no clue<br />

what a third of those vital genes do.<br />

So the ability to create life from<br />

scratch without nature’s help is still<br />

way beyond our capabilities.<br />

–Minimalist life–<br />

down the 901 genes of JCVIsyn1.0<br />

to the minimum for<br />

supporting life. With the help<br />

of transposons –“jumping<br />

genes” that insert themselves<br />

into sections of DNA and disrupt<br />

individual genes – the team<br />

tested which genes a bacterium<br />

can do without. They then<br />

designed a stripped-down<br />

genome, and inserted it into<br />

an existing cell that had had<br />

its own genome removed.<br />

But their first attempts at a<br />

minimalist cell didn’t succeed.<br />

“Every one of our designs failed<br />

because we based these on our<br />

existing knowledge base,”<br />

says Venter.<br />

Their breakthrough came when<br />

they realised that some genes<br />

they thought were expendable<br />

were actually crucial. “To get a<br />

viable cell, the researchers needed<br />

to make discoveries about many<br />

essential and semi-essential genes<br />

that we did not know about,” says<br />

Steven Benner of the Foundation<br />

for Applied Molecular Evolution<br />

in Alachua, Florida.<br />

Surprisingly, some 31 per cent<br />

of the vital genes have no known<br />

function, suggesting we may<br />

still have much to learn about<br />

the cellular processes crucial<br />

to maintaining life. “It means<br />

we know about two-thirds of<br />

essential biology,” says Venter.<br />

Hutchison says it is an “exciting<br />

possibility” that some of these<br />

genes perform key functions<br />

we don’t know of yet.<br />

It’s unclear how genes of<br />

such universal importance<br />

have ducked under the radar for<br />

so long. One possibility is that<br />

the mystery genes do actually<br />

code for known functions, but<br />

their sequences are so different<br />

from their equivalents in other<br />

organisms that we have not been<br />

able to spot and identify them.<br />

Once these mysterious extra<br />

genes were included, the minimal<br />

cells were found to live, grow and<br />

divide, forming clumps of cells in<br />

a dish of nutrients.<br />

Bacterial Eden<br />

Of the genes with known<br />

functions, most make proteins<br />

vital for survival, or check the<br />

fidelity of genome duplication<br />

when the cell divides. Other<br />

essential genes include ones<br />

that code for cell-membrane<br />

proteins and those that enable<br />

the organism to turn nutrients<br />

into energy.<br />

But Venter’s organism was<br />

produced in a bacterial Eden<br />

with every comfort provided,<br />

including a plentiful energy<br />

supply of easy-to-process glucose.<br />

In a harsher environment, such<br />

as soil or water, it would need<br />

extra genes to compete with rivals<br />

for resources, and to survive and<br />

6 | NewScientist | 2 April 2016

In this section<br />

■ Did a cosmic cloud kill the dinosaurs?, page 8<br />

■ The twins who felt fear for the first time, page 9<br />

■ Get immersed as first virtual reality games go on sale, page 18<br />

grow using scarcer sources of<br />

nutrients. “It is likely that their<br />

degree of ‘essential-ness’ will be<br />

environment-specific,”says Elfick.<br />

Next, the team plans to<br />

work out the functions of the<br />

mystery genes. What they find<br />

out could yield insights into<br />

how genes can be repurposed for<br />

synthetic biology, or enable us<br />

to design entirely new genomes<br />

for the first time (see “Life from<br />

scratch?”, below left).<br />

“What we’ve done is important<br />

because it is a step towards<br />

“Finding so many genes<br />

without a known function<br />

is exciting. It’s like the ‘dark<br />

matter’ of biology”<br />

completely understanding how a<br />

living cell works,” says Hutchison.<br />

“If we can really understand this,<br />

then we will be able to design cells<br />

efficiently for the production<br />

of pharmaceutical and other<br />

useful products.”<br />

Bioengineers have applauded<br />

the feat, but some are sceptical<br />

about the commercial potential.<br />

Some believe it is cheaper and<br />

more effective to tweak existing<br />

natural genomes, using<br />

techniques such as gene editing,<br />

than it is to build new genomes<br />

from the bottom up. “It’s a<br />

milestone,” says George Church<br />

of Harvard Medical School,<br />

who is a pioneer of CRISPR gene<br />

editing. “But the market will tell<br />

youifit’svaluable.”<br />

Such efforts to design synthetic<br />

life forms are often referred to<br />

as playing God, and frequently<br />

raise fears about their possible<br />

impact on the environment and<br />

human health. “If we’re already<br />

playing God, we’re not doing a<br />

particularly good job of it,” Elfick<br />

says. “Simply streamlining what’s<br />

already in nature doesn’t seem<br />

very God-like and, if anything, is<br />

a very humbling exercise.”<br />

He says we should not worry<br />

about this synthetic cell: “There<br />

are plenty of bugs already out<br />

there we should be much more<br />

worried about.” ■<br />

FEDERICO DE LUCA<br />

ONE MINUTE INTERVIEW<br />

Tiny but mighty<br />

A bacterium that can thrive with the smallest feasible string of<br />

synthetic genes is no vanity project, says Richard Kitney<br />

PROFILE<br />

Richard Kitney is a professor of biomedical<br />

systems engineering at Imperial College London,<br />

and co-director of the Centre for Synthetic<br />

Biology and Innovation. He was not involved<br />

in Craig Venter’s research<br />

What is the main advance with the creation of<br />

the smallest synthetic genome, JCVI-syn3.0?<br />

What Craig Venter’s team has done in making this<br />

minimal genome is to identify clear gaps in our<br />

knowledge about what makes a cell survive. They<br />

have essentially removed sections of the genome<br />

one by one to see what happens – in other words,<br />

to see if it dies and to try and understand why.<br />

What new insights has the bacterium given<br />

about life’s minimum requirements?<br />

The failure of a predecessor organism with even<br />

fewer genes led to the refinement of the rules for<br />

designing a genome, and identified a group of<br />

indispensable genes with functions we now need<br />

to investigate.<br />

What do you make of the fact that almost a<br />

third of the genes in syn3.0 have no known<br />

function, yet seem essential to life? What might<br />

they be doing?<br />

This is partially because of the incomplete state of<br />

knowledge within the field. As Venter’s team also<br />

points out, the tools used to match genes in syn3.0’s<br />

genome to comparable ones with known functions<br />

in other organisms may have failed to identify<br />

some genes because their sequences differ too<br />

much. It is of course an intriguing question as to<br />

what any unidentified genes do.<br />

Does the fact that Venter borrowed the<br />

“shell” of a different organism as a host and<br />

provided a perfect environment for growth<br />

detract from his achievement?<br />

Borrowing the shell of a naturally occurring<br />

bacterium is of course a major simplification of the<br />

technical challenge of making a synthetic organism.<br />

But it did allow the team to concentrate on the<br />

problem of genome minimisation–averylarge<br />

endeavour on its own. Because the researchers<br />

chose a rich growth medium, they could snip out<br />

many functions from the original host, as these<br />

are not needed when food is plentiful. What all<br />

this highlights is that there is in fact no universal<br />

minimal cell, only a minimal cell for a given set<br />

of conditions.<br />

Does the work offer clues about how<br />

life began?<br />

No, it tells us nothing about how life started<br />

naturally.<br />

There has been criticism that such work is<br />

a vanity project with no real scientific worth.<br />

Do you agree?<br />

Venter and his colleagues are serious researchers<br />

who are pursuing an important goal, so this is<br />

absolutely not a vanity project. It is an important<br />

step towards meeting synthetic biology’s need<br />

for stable, well-understood host cells that make<br />

and do useful things for us.<br />

Does it take us closer towards creating<br />

living organisms from scratch?<br />

This is not really a step forward in that sense.<br />

And where will the work go next?<br />

What is clear is that the host genome as<br />

presented has quite a way to go in terms of<br />

extending the catalogue of usable organisms<br />

available for synthetic biology.<br />

Interview by Andy Coghlan<br />

2 April 2016 | NewScientist | 7

THIS WEEK<br />

LYNN HILTON/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO<br />

Did a cosmic cloud<br />

kill off the dinos?<br />

Shannon Hall<br />

A NEBULAR winter could have<br />

doomed the dinosaurs. The clue is<br />

a thick layer of an extraterrestrial<br />

element on the ocean floor, now<br />

claimed to be the result of Earth<br />

colliding with a galactic cloud.<br />

The most-heard explanation<br />

for the dinosaurs’ demise is an<br />

asteroid impact, which left a<br />

crater off the coast of Mexico and<br />

a worldwide 30-centimetre-thick<br />

layer of iridium, an element<br />

otherwise rare on Earth.<br />

But every so often, astronomers<br />

suspect, the solar system ploughs<br />

into a giant nebula of molecular<br />

gas and dust much denser than<br />

typical interstellar space. The<br />

resulting galactic fog would have<br />

darkened skies and cooled the<br />

ground until a harsh winter set<br />

in. It would also have destroyed<br />

the ozone layer and halted<br />

photosynthesis.<br />

Now Tokuhiro Nimura of the<br />

Japan Spaceguard Association in<br />

Ibara and colleagues claim such<br />

a collision could have ended the<br />

dinosaurs’150-million-year reign.<br />

At a site in the Pacific Ocean, the<br />

team found an iridium-rich<br />

sediment layer 5 metres thick,<br />

too thick for a sudden event like<br />

an asteroid strike to account for it.<br />

They argue that a collision with<br />

a giant molecular cloud – which<br />

could take Earth at least a million<br />

years to pass through, picking<br />

up iridium steadily as it does so –<br />

fits the discovery much better.<br />

“Such an encounter and related<br />

perturbation in global climate [is]<br />

a more plausible explanation for<br />

the mass extinction than a single<br />

impact event,” they write (arxiv.<br />

org/abs/1603.06136).<br />

Adrian Melott at the University<br />

–No escaping this winter–<br />

of Kansas in Lawrence says the<br />

idea is wacky but not impossible.<br />

“We know that these clouds exist,”<br />

he says. “We know that we’re likely<br />

to run into one sooner or later.<br />

And they have some evidence<br />

from the ocean floor in favour of<br />

their idea.”<br />

Others question that evidence.<br />

David Kring at the Lunar and<br />

Planetary Institute in Houston,<br />

Texas, argues that the deposit<br />

could have been disturbed by<br />

currents, organisms and drilling,<br />

broadening the layer locally.<br />

“There have been several<br />

studies specifically designed to<br />

determine the thickness of the<br />

iridium anomaly,” he says. “They<br />

all indicate the anomaly is sharp,<br />

not broad,” which would favour<br />

the impact hypothesis.<br />

Even so, a collision with a cloud<br />

could have dislodged rocks from<br />

the fringes of the solar system and<br />

sent them hurtling toward Earth –<br />

perhaps explaining the crater and<br />

leaving a thin iridium layer intact.<br />

We could test this idea by<br />

searching the ocean floor for<br />

radioactive elements likely to<br />

be replenished from space, like<br />

uranium and plutonium, says<br />

Alexander Pavlov at NASA’s<br />

Goddard Space Flight Center in<br />

Maryland. Most uranium isotopes<br />

aren’t even found in the solar<br />

system, so finding them along<br />

with iridium would prove that<br />

something interstellar, like a vast<br />

nebula, was the true culprit. ■<br />

Asteroid shower<br />

brought a sea to<br />

young, dry Mars<br />

MARS may once have had an ocean –<br />

but only for a geological eye blink.<br />

This puts a dampener on ideas that<br />

there is or was life on the Red Planet.<br />

That’s according to a theory from<br />

Tim Parker of NASA’s Jet Propulsion<br />

Laboratory in Pasadena, California.<br />

Speaking at the Lunar and Planetary<br />

Science Conference in The Woodlands,<br />

Texas, in March, he argued that a<br />

sustained barrage of asteroids hitting<br />

the young Mars could have delivered<br />

short-lived water to the surface.<br />

Signs that Mars was once rife with<br />

water litter the surface. These include<br />

polygonal cracks seen by NASA’s<br />

Opportunity rover. On Earth, these<br />

require evaporation to form, so Parker<br />

sees them as an indication that the<br />

rover is traversing what was once the<br />

edge of an ocean. “The uniformity of<br />

the surface is much easier to explain<br />

in a shallow marine setting,” he says.<br />

But models of the ancient Mars<br />

climate require a thicker atmosphere<br />

to keep water liquid on the surface.<br />

This atmosphere must have somehow<br />

been rapidly lost to leave Mars as dry<br />

as we see it today.<br />

Now Parker and his colleagues say a<br />

tumultuous time in the solar system’s<br />

history known as the late heavy<br />

bombardment could provide the water<br />

with no need for a major change in the<br />

atmosphere. During this period about<br />

4 billion years ago, a barrage of<br />

asteroids is thought to have collided<br />

“This ocean would have<br />

frozen and disappeared –<br />

leavingverylittletimefor<br />

life to evolve”<br />

with the inner planets. Such asteroids<br />

could have brought water to an<br />

initially dry Mars, says Parker.<br />

Because Mars’s atmosphere<br />

was so thin, this ocean would have<br />

frozen and disappeared after just a<br />

few hundred million years – allowing<br />

very little time for life to evolve.<br />

“Tim is always thinking outside<br />

of the box,” says Devon Burr of the<br />

University of Tennessee, Knoxville.<br />

“There are a variety of ways of<br />

warming Mars and getting liquid<br />

water, I don’t know if the late heavy<br />

bombardment, for me, is conclusive.”<br />

Jacob Aron ■<br />

8 | NewScientist | 2 April 2016

For daily news stories, visit newscientist.com/news<br />

JOHN HOOGLAND<br />

Prairie dogs are<br />

serial killers of<br />

ground squirrel<br />

IT WAS thought to be just a small,<br />

furry grass-nibbler, but the whitetailed<br />

prairie dog has another life – as<br />

a serial killer. Some prairie dogs bite<br />

their ground squirrel neighbours to<br />

death on a regular basis, the first time<br />

that a mammalian herbivore has been<br />

seen killing other herbivores.<br />

What’s more, those who kill go on<br />

to produce more surviving offspring,<br />

improving their evolutionary fitness,<br />

say John Hoogland, a biologist at the<br />

University of Maryland Center for<br />

Environmental Science, and Charles<br />

Brown of the University of Tulsa,<br />

Oklahoma. The duo recorded<br />

163 killings of the squirrels over<br />

six years in the Arapaho National<br />

Wildlife Refuge in Colorado.<br />

Hoogland describes the killings<br />

as quick, subtle and unanticipated.<br />

While some prairie dogs chased the<br />

squirrels, others stalked them, waited<br />

outside their burrows or even dug<br />

babies out of their holes. They bit<br />

them to death, then abandoned<br />

the carcass and resumed foraging<br />

on nearby vegetation. “The killer<br />

supreme killed seven babies from the<br />

same litter in one day,” says Hoogland.<br />

Over the six years, about 47 prairie<br />

dogs killed squirrels, and 19 of<br />

them were serial slayers, including<br />

one female who dispatched nine<br />

squirrels over four years (Proceedings<br />

of the Royal Society B, doi.org/bdpv).<br />

For squirrels a competitor species<br />

can be as much of a risk as a predator.<br />

Aisling Irwin ■<br />

–Not going to eat that...–<br />

BRAND NEW IMAGES/GETTY<br />

‘Fearless’ twins show<br />

body affects emotions<br />

IS FEAR all in the mind – or body?<br />

Experiments on twins who can’t<br />

feel fear are suggesting that some<br />

emotions rely on us becoming<br />

aware of changes to our body.<br />

Many studies have shown that<br />

the amygdalae, two almondshaped<br />

structures in our brain,<br />

are crucial for feeling fear. People<br />

who have lost them through<br />

injury or disease also lose the<br />

ability to feel most kinds of fear.<br />

In 2013, Justin Feinstein, then<br />

at the University of Iowa in Iowa<br />

City, and his colleagues managed<br />

to scare three“fearless”people –<br />

two female identical twins and<br />

a woman known as S. M., all of<br />

whom had had their amygdalae<br />

destroyed by illness. Feinstein<br />

made them inhale carbon dioxide,<br />

giving them the sensation of<br />

choking. This was the first time<br />

that S. M. had experienced fear<br />

since she was a child. It showed<br />

that the amygdalae are not<br />

essential for all kinds of fear.<br />

One theory of emotion suggests<br />

that feelings are not generated<br />

directly by the brain, but through<br />

an awareness of our body. When<br />

–In tune with their body state–<br />

we see a spider, for example,<br />

the theory says we feel fear not<br />

because emotional centres of<br />

the brain are activated, but<br />

because the brain evaluates the<br />

situation and releases hormones<br />

such as adrenaline that increase<br />

“This seems to be evidence<br />

that extreme panic has<br />

different circuitry from<br />

normal fear”<br />

our heart rate and give us sweaty<br />

palms. It is our awareness of<br />

these changes to our body that<br />

we interpret as fear.<br />

Now Feinstein’s colleague<br />

Sahib Khalsa, at the University<br />

of Tulsa, Oklahoma, and his team<br />

have given the fearless twins a<br />

drug that mimics the action of<br />

adrenaline. High levels of this<br />

drug can cause temporary<br />

breathing difficulties and rapid<br />

heart palpitations. The team<br />

asked the twins and a group of<br />

volunteers with intact amygdalae<br />

to rate their experience of these<br />

changes on a scale from 0 to 10.<br />

Both twins had the same<br />

physical reaction as the other<br />

volunteers – their heart and<br />

breathing rates increased. But<br />

only one twin said she was aware<br />

of both these changes, rating her<br />

breathing problems as a 10 on the<br />

scale. She also reported a choking<br />

sensation and had a panic attack.<br />

The volunteers also noted<br />

breathing difficulties and a<br />

quarter had panic attacks.<br />

The other twin noted a slight<br />

awareness of her heart rate<br />

changing, but she rated her<br />

physical symptoms as close<br />

to zero and did not panic.<br />

The results indicate that<br />

there are mechanisms beyond<br />

the amygdalae that are involved<br />

in fear and anxiety, and support<br />

the theory that an awareness of<br />

physiological changes may be<br />

necessary to experience some<br />

kinds of emotion (The Journal<br />

of Neuroscience, doi.org/bdpz).<br />

However, the fact that the<br />

twins – who both have damaged<br />

amygdalae because of a rare<br />

genetic condition – had different<br />

responses suggests there may be<br />

environmental factors at play, too.<br />

“This seems to be more evidence<br />

that extreme panic has its own<br />

underlying circuitry that is<br />

different from normal fear,”<br />

says Nick Medford, who studies<br />

consciousness and emotion at the<br />

Sackler Centre for Consciousness<br />

Science in Brighton, UK.<br />

Further experiments involving<br />

scanning the twins’ brains while<br />

they experience fear would help<br />

us identify mechanisms of<br />

emotion in the brain, says Khalsa.<br />

Such studies could also lead to<br />

alternative treatments for anxiety<br />

disorders. There is some evidence<br />

to suggest that people who have<br />

abnormal awareness of their<br />

bodily functions are more prone<br />

to anxiety and depression.<br />

“If you could pinpoint neural<br />

regions responsible for our<br />

awareness of our body state and<br />

the different mechanisms that<br />

generate fearful feelings, you<br />

might have new targets to<br />

modulate or reduce anxiety,”<br />

says Khalsa. Helen Thomson ■<br />

2 April 2016 | NewScientist | 9

THIS WEEK<br />

Emissions reveal<br />

a constructive side<br />

Richard Schiffman<br />

TAKING carbon dioxide out of the<br />

atmosphere is crucial to slowing<br />

the progress of climate change.<br />

But rather than lock all that CO 2<br />

away underground, what if we<br />

could use it to make things?<br />

That’s the aim of a pilot plant<br />

at the University of Newcastle<br />

near Sydney, Australia.<br />

Launched last week, the plant<br />

will test the commercial potential<br />

of mineral carbonation, a process<br />

that forms stable materials by<br />

chemically binding CO 2<br />

to<br />

minerals containing calcium or<br />

magnesium. The plant will bind<br />

the gas into crushed serpentinite<br />

rocks to create magnesium<br />

carbonate, which can be used to<br />

produce cement, paving stones<br />

and plasterboard.<br />

It could be a way of<br />

“permanently and safely<br />

disposing of CO 2<br />

and making<br />

useful products in the process”,<br />

says Klaus Lackner of Arizona<br />

State University in Tempe,<br />

who pioneered the technique<br />

in the lab.<br />

The process happens naturally<br />

when rocks are gradually<br />

MINERAL CARBONATION INTERNATIONAL<br />

weathered by exposure to CO 2<br />

in the air. This helped cut the<br />

proportion of the gas in the<br />

ancient atmosphere to levels<br />

low enough for life to flourish,<br />

says Geoff Brent, senior<br />

scientist at Orica, an explosives<br />

– Made with greenhouse gases–<br />

manufacturer based in Melbourne.<br />

His firm is supplying the plant<br />

with CO 2<br />

– a by-product of making<br />

ammonium nitrate.<br />

But we can’t afford to wait<br />

millions of years for geology<br />

to rid the atmosphere of our<br />

greenhouse emissions. “It’s about<br />

turning the natural process into<br />

a large-scale industrial process<br />

on our required timescale – which<br />

is extremely urgent,” says Brent.<br />

There are several challenges.<br />

Mining for serpentinite is energyintensive<br />

and damaging to the<br />

environment, for one thing.<br />

But Brent says the rock is one of<br />

the most common on Earth, and<br />

that carbonation plants could<br />

be built near mining areas to<br />

reduce transport emissions.<br />

Another objection is that<br />

mineral carbonation costs too<br />

much compared with storing<br />

CO 2<br />

underground. However,<br />

underground storage has its own<br />

problems: suitable repositories<br />

are hard to find and there is a risk<br />

that the gas may one day escape.<br />

“Carbonation is more secure in<br />

the long term, because there is no<br />

danger of leakage and no need to<br />

maintain long gas pipelines and<br />

transportation infrastructure to<br />

move the CO 2<br />

, since we will be<br />

obtaining it on-site,” says Brent.<br />

“The whole point of the<br />

project is to get the price down<br />

low enough,” says Marcus Dawe,<br />

CEO of Mineral Carbonation<br />

International, the firm<br />

coordinating the effort. “It is<br />

all about how we can make<br />

this economical.”<br />

Dawe and his team are<br />

optimistic that they will make<br />

progress by the end of the 18-<br />

month pilot project. But for<br />

mineral carbonation to take off,<br />

there will need to be a higher<br />

price on carbon, says Dawe,<br />

because right now “nothing is<br />

more economical than putting<br />

CO 2<br />

in the air”. ■<br />

Is calcium boost<br />

behind brain<br />

zap effects?<br />

WE MAY finally be figuring out how<br />

an increasingly popular therapy that<br />

uses electricity to boost the brain’s<br />

functioning has its effects – by<br />

pushing up levels of calcium in cells.<br />

Transcranial direct current<br />

stimulation (tDCS) has been linked to<br />

effects such as accelerated learning<br />

and improving the symptoms of<br />

depression. It involves using<br />

electrodes to send a weak current<br />

across the brain, which proponents<br />

think changes the electrical<br />

properties of neurons, leading<br />

to changes in their connectivity.<br />

But the cellular mechanisms that<br />

lead to such broad neurological<br />

changes are not clear and some are<br />

doubtful that tDCS has any effect on<br />

the brain. Despite this, devices are<br />

being developed to sell to people<br />

keen to influence their own brains.<br />

Now Hajime Hirase at the RIKEN<br />

Brain Science Institute in Tokyo,<br />

Japan, and his colleagues have an<br />

answer. They have identified sudden<br />

surges in calcium flow in the brains of<br />

mice seconds after they receive low<br />

doses of tDCS. The surges start in<br />

star-shaped cells called astrocytes<br />

that strengthen connections between<br />

neurons and regulate the electrical<br />

signals that pass between them.<br />

The team used mice that had been<br />

engineered to show depression-like<br />

symptoms, such as struggling less<br />

against restraints. After they had<br />

received tDCS, the mice struggled<br />

for longer. The same effect didn’t<br />

happen in mice whose calcium<br />

“By triggering calcium<br />

surges, tDCS may<br />

be interfering with<br />

neuron connectivity”<br />

signalling had been disabled (Nature<br />

Communications, doi.org/bdr2).<br />

Astrocytes use calcium to manage<br />

the flow of information between<br />

neurons, and these findings suggest<br />

that tDCS artificially boosts the<br />

process. Hirase thinks calcium<br />

signalling may also be behind other<br />

suggested effects of tDCS, such as<br />

improved memory.<br />

Understanding the link between<br />

tDCS and calcium could dispel doubts<br />

about the technique. “Scepticism is<br />

not so much about tDCS itself as it is<br />

about inflated expectations,” says<br />

Walter Paulus of the University of<br />

Göttingen in Germany. Sally Adee ■<br />

10 | NewScientist | 2 April 2016

F<br />

I<br />

N<br />

Subscribe now for less than $2 per week,<br />

and discover a whole world of new ideas<br />

and inspiration<br />

Visit newscientist.com/8823 or call<br />

1-888-822-3242 and quote offer 8823<br />

#LiveSmarter<br />

CYRUS CORNUT/DOLCE VITA/PICTURETANK

THIS WEEK<br />

NASA/JPL-CALTECH/UCLA/MPS/DLR/IDA/PSI/LPI<br />

Bright spots and<br />

ice dazzle on Ceres<br />

Jacob Aron, The Woodlands, Texas<br />

LET’S take a look inside. The latest<br />

from NASA’s Dawn probe, which<br />

has been in orbit around the dwarf<br />

planet Ceres since April last year,<br />

suggests this tiny world has water<br />

ice on the surface and craters that<br />

provide a window on its interior.<br />

A spectacular view of the<br />

beguiling bright spots at the heart<br />

of the 92-kilometre-wide Occator<br />

crater from just 375 kilometres up,<br />

shown above, was just one of the<br />

latest findings unveiled by the<br />

mission team at the Lunar and<br />

Planetary Science Conference<br />

in The Woodlands, Texas, on<br />

22 March.<br />

These spots have perplexed<br />

researchers since Dawn first<br />

reached Ceres, the largest object<br />

in the asteroid belt. Probing their<br />

nature could give clues to Ceres’s<br />

interior. In the new image, Dawn<br />

has seen colour variations across<br />

the surface of the bright regions.<br />

These wouldn’t be visible to the<br />

human eye, but reflect possible<br />

differences in the composition<br />

of the material seen by Dawn.<br />

This close-in view reveals that<br />

the central bright spot actually<br />

sits within a 10-kilometre-wide<br />

depression inside the crater.<br />

At the centre of that is a small<br />

mound. “We’re starting to see<br />

how complex the distribution of<br />

the bright material is,” said Carol<br />

Raymond of NASA’s Jet Propulsion<br />

Laboratory in California.<br />

How this arrangement formed<br />

is still a mystery. Timothy Bowling<br />

at the University of Chicago<br />

presented a possible explanation,<br />

“Seeing water ice anywhere<br />

on Ceres is a surprise – it<br />

is warm enough at the<br />

surface for it to evaporate”<br />

in which a meteorite smacked<br />

into Ceres, exposing icy material<br />

from as much as 40 kilometres<br />

below the surface and heating it up.<br />

As this material settled into the<br />

Occator crater we see today, the<br />

water would evaporate, leaving<br />

bright salt and minerals behind.<br />

The floor of Occator is also<br />

riddled with fractures that<br />

seem to be older than the crater<br />

itself. These could have provided<br />

an escape route for material<br />

How to stack<br />

oranges in 24<br />

dimensions<br />

IT’S a tight squeeze. Mathematicians<br />

have proved that they know the<br />

best way to pack spheres in eight<br />

and 24 dimensions – the first time<br />

this problem has been solved in a<br />

new dimension for almost 20 years.<br />

“I think they’re fantastic results. I’m<br />

excited that this has been done at last,”<br />

says Thomas Hales at the University<br />

of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.<br />

The sphere-packing problem asks<br />

a deceptively simple question: what<br />

–Beguiling brightness– arrangement crams the most spheres<br />

into a limited volume? It is easy to<br />

beneath the surface.<br />

describe, but difficult to prove.<br />

The team behind Dawn has also In 1611, Johannes Kepler suggested<br />

made an unexpected discovery: that the best arrangement for<br />

water ice hiding in a crater. The 3-dimensional spheres like oranges<br />

10-kilometre-wide Oxo crater is a pyramid. But it took until 1998<br />

seems to have formed relatively for Hales to publish a proof – and<br />

recently. The find comes from another 16 years to formally verify it.<br />

spectral data taken during Dawn’s Meanwhile, mathematicians have<br />

higher orbit in June last year.<br />

been gunning for higher dimensions.<br />

Seeing water ice anywhere on Now, Maryna Viazovska at Humboldt<br />

Ceres is a surprise as it is warm University of Berlin has proved that<br />

enough at the surface for any<br />

a grid called the E8 lattice is the best<br />

ice to evaporate into space. That packing in eight dimensions (arxiv.<br />

means it must have been exposed org/abs/1603.04246v1). Almost<br />

recently, said Jean-Philippe<br />

immediately after, she teamed up<br />

Combe of the Bear Fight Institute with other researchers to prove that<br />

in Winthrop, Washington. “This a related arrangement called the<br />

area is possibly a cold trap where Leech lattice is best in 24 dimensions<br />

H 2<br />

0-rich materials could be<br />

(arxiv.org/abs/1603.06518v1).<br />

preserved for at least some time,” The fact that these dimensions<br />

he said.<br />

were next to fall is no coincidence.<br />

So where has this water<br />

For reasons we don’t understand,<br />

come from? Models of Ceres’s such lattices don’t show up in other<br />

formation, along with the<br />

dimensions. But they were suspected<br />

sightings of bright spots like the to be the most efficient arrangements<br />

ones at Occator, suggest the dwarf in the dimensions they apply to.<br />

planet has an icy sub-surface layer “These are unbelievably good<br />

that is mixed up with salt and packings,” says Henry Cohn at<br />

rock. The ice at Oxo could have Microsoft Research New England in<br />

been exposed by a landslide,<br />

Cambridge, Massachusetts. “The<br />

or dug up by a meteorite.<br />

spheres in these dimensions fit<br />

Dawn will continue to gather perfectly, in ways that don’t happen<br />

data about Ceres until August at in other dimensions.”<br />

least, and possibly into next year. Packing spheres in 24 dimensions<br />

But some questions about this isn’t just a mathematical game. The<br />

enigmatic world may not<br />

problem has applications in wireless<br />

be answered until a repeat visit. communication, and has been used to<br />

“It would be nice to land there, communicate with spacecraft in the<br />

wouldn’t it?” said Raymond. ■ distant solar system. Lisa Grossman ■<br />

12 | NewScientist | 2 April 2016

Cognitive Behavioral<br />

Therapy: Techniques for<br />

Retraining Your Brain<br />

Conquer Your Bad<br />

Thoughts and Habits<br />

70%<br />

LIMITED TIME OFFER<br />

off<br />

ORDER BY APRIL 12<br />

Why is it so hard to lose weight, stop smoking, or establish healthy<br />

habits? Why do couples argue about the same issues over and over? Why<br />

do so many people lie awake at night, stricken with worry and anxiety?<br />

The answers to these questions—and the path to lasting change in your<br />

life—lie in cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). Developed on a proven<br />

foundation of neurological and behavioral research, CBT is a welltested<br />

collection of practical techniques for managing goal-oriented<br />

change. Build a toolkit of CBT techniques as you to take on the role of<br />

medical student, physician, psychologist, and patient, and learn how to<br />

create lasting change in your life.<br />

Offer expires 04/12/16<br />

<strong>THE</strong>GREATCOURSES.COM/4NSUSA<br />

1-800-832-2412<br />

Taught by Professor Jason M. Satterfield<br />

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN FRANCISCO<br />

LECTURE TITLES<br />

1. Cognitive Behavioral Foundations<br />

2. Quantified Self-Assessment for Therapy<br />

3. Setting Therapeutic Goals<br />

4. Third-Wave Cognitive Behavioral Therapy<br />

5. Stress and Coping<br />

6. Anxiety and Fear<br />

7. Treating Depression<br />

8. Anger and Rage<br />

9. Advanced Cognitive Behavioral Therapy<br />

10. Positive Psychology<br />

11. Healing Traumatic Injuries<br />

12. Forgiveness and Letting Go<br />

13. Digging Deep and Finding Meaning<br />

14. Cognitive Behavioral<br />

Therapy and Medicine<br />

15. Staying on the Wagon<br />

16. Thinking Healthy: Weight and Nutrition<br />

17. Behavioral Therapy for<br />

Chemical Addictions<br />

18. Getting a Good Night’s Sleep<br />

19. Mastering Chronic Pain<br />

20. Building and Deepening Relationships<br />

21. Constructive Conflict and Fighting Fair<br />

22. Thriving at Work through<br />

Behavioral Health<br />

23. Developing Emotional Flexibility<br />

24. Finding the Best Help<br />

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy:<br />

Techniques for Retraining Your Brain<br />

Course no. 9631 | 24 lectures (30 minutes/lecture)<br />

SAVE UP TO $190<br />

DVD $269.95 NOW $79.95<br />

CD $199.95 NOW $59.95<br />

+$10 Shipping, Processing, and Lifetime Satisfaction Guarantee<br />

Priority Code: 127962<br />

For over 25 years, The Great Courses has brought<br />

the world’s foremost educators to millions who<br />

want to go deeper into the subjects that matter<br />

most. No exams. No homework. Just a world of<br />

knowledge available anytime, anywhere. Download<br />

or stream to your laptop or PC, or use our free<br />

mobile apps for iPad, iPhone, or Android. Over 550<br />

courses available at www.TheGreatCourses.com.

LET YOUR LOVE LIFE LIFT OFF<br />

ON<br />

NEW SCIENTIST CONNECT<br />

Join now<br />

FOR<br />

FREE<br />

We all know it’s not rocket science trying to find that special<br />

someone with whom we connect, even though it sometimes feels<br />

that way. Which is why we’ve launched New Scientist Connect.<br />

Meet like-minded people who share similar interests to you –<br />

whether you’re looking for love, or just to meet someone on the<br />

same wavelength, no matter where you are in the world.<br />

Launch your search now at: http://dating.newscientist.com

IN BRIEF<br />

JOHN WATKINS/FLPA/CORBIS<br />

Migrating birds arrive in the<br />

UKearlierandleavelater<br />

SOME common migrating birds – including the blackcap,<br />

(pictured above) – are staying in the UK for two weeks<br />

or more longer than half a century ago. “We knew that<br />

birds were arriving earlier in spring, but this is the first<br />

study I know of in Europe that has also tracked when they<br />

leave in autumn,” says Stuart Newson of the British Trust<br />

for Ornithology.<br />

Newson has tapped into amateur observations of bird<br />

migrations collected over more than 50 years, starting<br />

with paper files in the 1960s and ending with 800,000<br />

records from BirdTrack, an internet-based volunteer<br />

Ghostgalaxiesarefullofdarkmatter<br />

<strong>THE</strong>RE’S more than meets the eye.<br />

A so-called ultra-diffuse galaxy<br />

has been found to consist of over<br />

99.96 per cent dark matter.<br />

An ultra-diffuse galaxy is a<br />

huge galaxy with relatively few<br />

stars widely spread out, so it looks<br />

ghostly and is hard to study.<br />

The fact that they hold their<br />

shape makes researchers think<br />

such galaxies must consist of at<br />

least 98 per cent dark matter – the<br />

stuff thought to make up about<br />

80 per cent of the mass in the<br />

universe overall. But no one<br />

had directly measured it.<br />

Now Michael Beasley at the<br />

Institute of Astrophysics of the<br />

Canary Islands, Spain, and his<br />

colleagues have “weighed” an<br />

ultra-diffuse galaxy in the<br />

Virgo cluster named VCC 1287.<br />

The team measured the speeds<br />

of seven globular star clusters<br />

observation network, to study 14 common migrating<br />

birds. He found that 11 species arrive earlier and four<br />

leave later (Ibis, doi.org/bdpr).<br />

Amateur data is best, he says. Professional<br />

ornithologists have mostly counted birds arriving at a<br />

handful of coastal observation points. And many previous<br />

studies concentrated on dating the first birds to arrive.<br />

Observations from citizen scientists avoid such biases,<br />

and cover leaving times too.<br />

One reason for late leaving could be that females are<br />

laying more than one clutch of eggs thanks to the longer<br />

breeding season, says Tim Sparks of Coventry University,<br />

UK. Indeed, the study also shows that birds taking most<br />

advantage of earlier springs and balmy late autumns,<br />

such as the blackcap, are increasing in number.<br />

orbiting the galaxy, a clue to how<br />

much mass it contains, and found<br />

that it must have about 80 billion<br />

times more mass than the sun<br />

and 3000 times more dark matter<br />

than stellar mass (Astrophysical<br />

Journal Letters, doi.org/bdpb).<br />

VCC 1287 was probably born<br />

with both dark matter and gas<br />

but lost the latter as it fell into<br />

the Virgo cluster. Without gas,<br />

it couldn’t create new stars, so it<br />

ended up with lots of dark matter<br />

but little light.<br />

Exercise keeps<br />

your brain younger<br />

YOUNG in body, young in mind.<br />

Older people who are physically<br />

active seem to stave off memory<br />

loss – but only if they start early.<br />

Clinton Wright at the University<br />

of Miami in Florida and his<br />

colleagues followed 876 people,<br />

starting at an average age of 71,<br />

over five years. At the end, the<br />

brains of non-exercisers looked<br />

10 years older than those who<br />

did moderate exercise. Those<br />

who exercised also showed<br />

less memory loss (Neurology,<br />

doi.org/bdpw).<br />

These effects are associated<br />

with better vascular health,<br />

suggesting that exercise helps<br />

the brain by keeping down blood<br />

pressure and preventing strokes.<br />

But the team’s results showed<br />

that physical activity can only<br />

delay memory loss if a person<br />

begins exercising before the<br />

onset of symptoms. “Once<br />

there’s damage, you can’t really<br />

reverse it,” says Wright.<br />

Why we have really<br />

big noses…<br />

IT’S an evolutionary mystery<br />

that’s literally as plain as the<br />

nose on your face. Why did our<br />

ancestors develop a prominent<br />

protruding nose when most<br />

primates have flat nasal openings?<br />

A new study suggests that our<br />

unusual nose may simply be a byproduct<br />

of other, more important<br />

changes in the structure of our<br />

face as our brains enlarged.<br />

Takeshi Nishimura at Kyoto<br />

University, Japan, and his team<br />

modelled the flow of inhaled air<br />

through the nasal passages of<br />

humans, chimpanzees and<br />

macaques. It turns out that our<br />

noses, unlike those of other<br />

primates, are poor at warming or<br />

cooling air that goes to the lungs<br />

(PLoS Computational Biology, DOI:<br />

10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004807).<br />

2 April 2016 | NewScientist | 15

IN BRIEF<br />

For new stories every day, visit newscientist.com/news<br />

E BRUN<br />

Leaded ink opens<br />

up ancient scrolls<br />

LEAD often gets a bad press. But its<br />

discovery in ancient Graeco-Roman<br />

ink could make it easier to read an<br />

early form of publishing – precious<br />

scrolls buried by the eruption of<br />

Mount Vesuvius in AD 79.<br />

Some 800 scrolls, part of the<br />

classical world’s best-surviving<br />

library, have tantalised scholars<br />

since they were unearthed in a<br />

villa in the ancient Roman city of<br />

Herculaneum in 1752. About 200<br />

are in such a delicate state that they<br />

have never been read. Unrolling the<br />

charred scrolls could destroy them,<br />

so people have been X-raying the<br />

bundles in the hopes of decoding<br />

the writing inside. But progress has<br />

been slow – it is difficult to detect<br />

the difference between the letters<br />

and the papyrus they are written on.<br />

Now physicist Vito Mocella of<br />

the Italian National Research Council<br />

and his colleagues have discovered<br />

lead in the ink on two Herculaneum<br />

papyri fragments held in the<br />

Institute of France in Paris. The<br />

presence of lead means that<br />

imaging techniques could be<br />

recalibrated to pick up the metal,<br />

something X-rays excel at (PNAS,<br />

doi.org/bdn5).<br />

“This really opens up the<br />

possibility of being able to read<br />

these scrolls,” says Graham Davis,<br />

at Queen Mary University of London.<br />

“If this is typical of this scroll or other<br />

scrolls, than that is very good news.”<br />

Violent pirouette spun off the moon’s water<br />

BALLET doesn’t suit everyone.<br />

Molten rock flowing beneath the<br />

moon’s crust billions of years ago<br />

shifted its spin axis by about six<br />

degrees. The pirouette could have<br />

cost the moon most of its water.<br />

We saw the first direct evidence<br />

of water on the moon in 2009,<br />

when a deliberately crashed<br />

satellite found hydrogen – a proxy<br />

for water – in a southern crater.<br />

There was more there than at the<br />

actual pole, a little more than five<br />

degrees away, says Matthew<br />

Siegler of the Planetary Science<br />

Institute in Tucson, Arizona.<br />

Fungi may help<br />

woodpeckers drill<br />

IF A red-cockaded woodpecker<br />

wants a home, it does more than<br />

just knock on wood – it takes some<br />

tiny helpers with it. It seems to<br />

carry spores of wood-rotting fungi<br />

to each new hole.<br />

Red-cockaded woodpeckers<br />

live in the pine forests of the<br />

south-eastern US, where they dig<br />