Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

FORYOURCONSIDERATION<br />

BY JEFF HESTER<br />

Not the end of<br />

science<br />

The emerging science<br />

of process<br />

I<br />

picked up a copy of John<br />

Horgan’s The End of<br />

Science the other day.<br />

Horgan is a good writer<br />

with impressive rhetorical<br />

skill, but the book itself is a<br />

travesty. Horgan is a true<br />

believer that we have reached<br />

the end of what science can tell<br />

us, leaving him keenly attuned<br />

to things that might support<br />

his faith, but deaf to things<br />

that do not.<br />

What I saw in Horgan’s<br />

prose more than anything was<br />

a mixture of hubris and failed<br />

imagination. The future of<br />

science will, without question,<br />

be different from its past. But<br />

Horgan seems convinced that<br />

because he, personally, cannot<br />

envision what that future will<br />

be, it must be a dead end.<br />

From where I sit, things<br />

look different. Last month, I<br />

wrote about tiers of scientific<br />

thought. From observation, to<br />

catalogs and categorization,<br />

to predictive description, to<br />

explanation and a search for<br />

mechanism and physical law,<br />

science has come a long way.<br />

But while science continues to<br />

delve aggressively into the fundamental<br />

nature of reality, the<br />

last century and a half has also<br />

seen something different.<br />

Rather than looking for<br />

new physical laws or testing<br />

ever more esoteric theoretical<br />

predictions of those laws, scientists<br />

are increasingly asking<br />

a different sort of question:<br />

“Once you know the rules and<br />

the way pieces move, how does<br />

the game unfold?”<br />

For want of something better,<br />

I’ll call this kind of science<br />

the “science of process.”<br />

I need to be clear that I<br />

am not talking about process<br />

in the way an engineer does.<br />

Engineers begin with a goal,<br />

and then design processes to<br />

accomplish that end. To an<br />

engineer, process is inherently<br />

teleological, meaning it embodies<br />

the last of Aristotle’s four<br />

causes: purpose.<br />

But the science of process has<br />

nothing to do with Aristotle’s<br />

philosophy. Purpose is superfluous.<br />

Instead, the science<br />

of process asks what happens<br />

when you throw all of our<br />

observations, descriptions, and<br />

physical laws into a pot and put<br />

it on to boil.<br />

Looking forward in time, the<br />

science of process asks, “Given<br />

the way things work, what will<br />

happen next?” Looking back<br />

into the past it asks, “Given the<br />

way things work, how did we<br />

get here?”<br />

Once recognized, the emergence<br />

of the science of process<br />

is not difficult to see. A century<br />

ago, cutting-edge astronomy<br />

meant classifying stars and galaxies<br />

and discovering the sizes<br />

of things. In sharp contrast,<br />

astronomy today looks at the<br />

process of star formation and<br />

evolution, the process of galaxy<br />

and structure formation, and<br />

even the processes that gave rise<br />

to physical law itself.<br />

<strong>Astronomy</strong> is hardly alone.<br />

Modern geology and planetary<br />

science are built on processes<br />

such as tectonism, volcanism,<br />

impacts, and gradation. Medical<br />

research talks less of organs and<br />

their function, and more about<br />

processes and their interactions.<br />

The exploding field of brain science<br />

looks at learning, memory,<br />

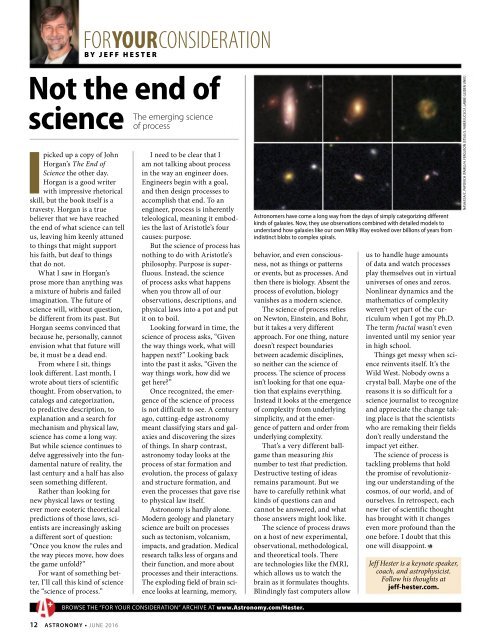

Astronomers have come a long way from the days of simply categorizing different<br />

kinds of galaxies. Now, they use observations combined with detailed models to<br />

understand how galaxies like our own Milky Way evolved over billions of years from<br />

indistinct blobs to complex spirals.<br />

behavior, and even consciousness,<br />

not as things or patterns<br />

or events, but as processes. And<br />

then there is biology. Absent the<br />

process of evolution, biology<br />

vanishes as a modern science.<br />

The science of process relies<br />

on Newton, Einstein, and Bohr,<br />

but it takes a very different<br />

approach. For one thing, nature<br />

doesn’t respect boundaries<br />

between academic disciplines,<br />

so neither can the science of<br />

process. The science of process<br />

isn’t looking for that one equation<br />

that explains everything.<br />

Instead it looks at the emergence<br />

of complexity from underlying<br />

simplicity, and at the emergence<br />

of pattern and order from<br />

underlying complexity.<br />

That’s a very different ballgame<br />

than measuring this<br />

number to test that prediction.<br />

Destructive testing of ideas<br />

remains paramount. But we<br />

have to carefully rethink what<br />

kinds of questions can and<br />

cannot be answered, and what<br />

those answers might look like.<br />

The science of process draws<br />

on a host of new experimental,<br />

observational, methodological,<br />

and theoretical tools. There<br />

are technologies like the fMRI,<br />

which allows us to watch the<br />

brain as it formulates thoughts.<br />

Blindingly fast computers allow<br />

us to handle huge amounts<br />

of data and watch processes<br />

play themselves out in virtual<br />

universes of ones and zeros.<br />

Nonlinear dynamics and the<br />

mathematics of complexity<br />

weren’t yet part of the curriculum<br />

when I got my Ph.D.<br />

The term fractal wasn’t even<br />

invented until my senior year<br />

in high school.<br />

Things get messy when science<br />

reinvents itself. It’s the<br />

Wild West. Nobody owns a<br />

crystal ball. Maybe one of the<br />

reasons it is so difficult for a<br />

science journalist to recognize<br />

and appreciate the change taking<br />

place is that the scientists<br />

who are remaking their fields<br />

don’t really understand the<br />

impact yet either.<br />

The science of process is<br />

tackling problems that hold<br />

the promise of revolutionizing<br />

our understanding of the<br />

cosmos, of our world, and of<br />

ourselves. In retrospect, each<br />

new tier of scientific thought<br />

has brought with it changes<br />

even more profound than the<br />

one before. I doubt that this<br />

one will disappoint.<br />

Jeff Hester is a keynote speaker,<br />

coach, and astrophysicist.<br />

Follow his thoughts at<br />

jeff-hester.com.<br />

NASA/ESA/C. PAPOVICH (TAMU)/H. FERGUSON (STSCI)/S. FABER (UCSC)/I. LABBÉ (LEIDEN UNIV.)<br />

BROWSE THE “FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION” ARCHIVE AT www.<strong>Astronomy</strong>.com/Hester.<br />

12 ASTRONOMY • JUNE 2016