You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

E<br />

SECRETSKY<br />

Part of the wonder of<br />

backyard observing<br />

is that we, with our<br />

modest telescopes,<br />

can probe deeply<br />

into the universe. And by<br />

pushing the limits of those<br />

instruments, we can edge ever<br />

closer to the beginning of time<br />

— not as close as Hubble, but<br />

close nevertheless.<br />

In the June night sky after<br />

sunset, two quasars, one much<br />

more distant than the other,<br />

culminate for visual observers.<br />

Quasars are the universe’s<br />

most luminous objects. They<br />

represent the blazing cores of<br />

early galaxies whose tremendous<br />

light output (each is billions<br />

of times more luminous<br />

than our Sun) comes from gas<br />

falling into a supermassive<br />

black hole.<br />

As the gas spirals inward, it<br />

unleashes a tsunami of raw<br />

energy into space. So powerful<br />

are quasars that, despite their<br />

vast distances (billions of lightyears),<br />

we amateur astronomers<br />

can spot the brightest<br />

ones through even modest<br />

telescopes.<br />

BY STEPHEN JAMES O’MEARA<br />

Halfway to the<br />

edge<br />

You can view an amazingly distant<br />

object this month.<br />

N<br />

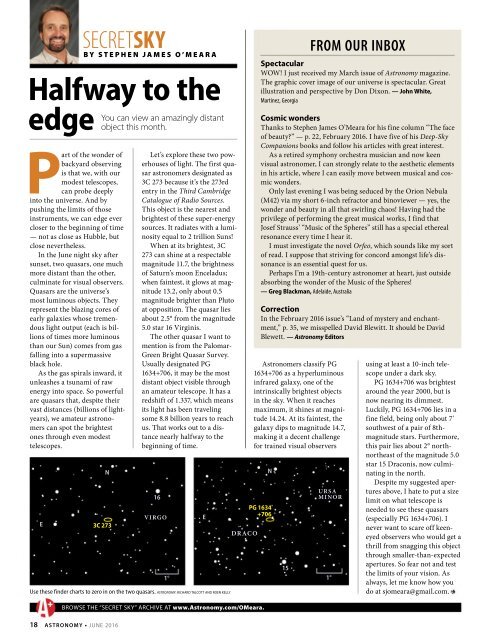

3C 273<br />

Let’s explore these two powerhouses<br />

of light. The first quasar<br />

astronomers designated as<br />

3C 273 because it’s the 273rd<br />

entry in the Third Cambridge<br />

Catalogue of Radio Sources.<br />

This object is the nearest and<br />

brightest of these super-energy<br />

sources. It radiates with a luminosity<br />

equal to 2 trillion Suns!<br />

When at its brightest, 3C<br />

273 can shine at a respectable<br />

magnitude 11.7, the brightness<br />

of Saturn’s moon Enceladus;<br />

when faintest, it glows at magnitude<br />

13.2, only about 0.5<br />

magnitude brighter than Pluto<br />

at opposition. The quasar lies<br />

about 2.5° from the magnitude<br />

5.0 star 16 Virginis.<br />

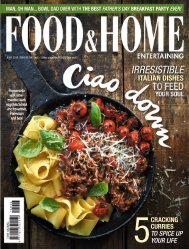

The other quasar I want to<br />

mention is from the Palomar-<br />

Green Bright Quasar Survey.<br />

Usually designated PG<br />

1634+706, it may be the most<br />

distant object visible through<br />

an amateur telescope. It has a<br />

redshift of 1.337, which means<br />

its light has been traveling<br />

some 8.8 billion years to reach<br />

us. That works out to a distance<br />

nearly halfway to the<br />

beginning of time.<br />

16<br />

VIRGO<br />

Use these finder charts to zero in on the two quasars. ASTRONOMY: RICHARD TALCOTT AND ROEN KELLY<br />

1°<br />

E<br />

DRACO<br />

N<br />

PG 1634<br />

+706<br />

BROWSE THE “SECRET SKY” ARCHIVE AT www.<strong>Astronomy</strong>.com/OMeara.<br />

Astronomers classify PG<br />

1634+706 as a hyperluminous<br />

infrared galaxy, one of the<br />

intrinsically brightest objects<br />

in the sky. When it reaches<br />

maximum, it shines at magnitude<br />

14.24. At its faintest, the<br />

galaxy dips to magnitude 14.7,<br />

making it a decent challenge<br />

for trained visual observers<br />

15<br />

FROM OUR INBOX<br />

Spectacular<br />

WOW! I just received my March issue of <strong>Astronomy</strong> magazine.<br />

The graphic cover image of our universe is spectacular. Great<br />

illustration and perspective by Don Dixon. — John White,<br />

Martinez, Georgia<br />

Cosmic wonders<br />

Thanks to Stephen James O’Meara for his fine column “The face<br />

of beauty?” — p. 22, February 2016. I have five of his Deep-Sky<br />

Companions books and follow his articles with great interest.<br />

As a retired symphony orchestra musician and now keen<br />

visual astronomer, I can strongly relate to the aesthetic elements<br />

in his article, where I can easily move between musical and cosmic<br />

wonders.<br />

Only last evening I was being seduced by the Orion Nebula<br />

(M42) via my short 6-inch refractor and binoviewer — yes, the<br />

wonder and beauty in all that swirling chaos! Having had the<br />

privilege of performing the great musical works, I find that<br />

Josef Strauss’ “Music of the Spheres” still has a special ethereal<br />

resonance every time I hear it.<br />

I must investigate the novel Orfeo, which sounds like my sort<br />

of read. I suppose that striving for concord amongst life’s dissonance<br />

is an essential quest for us.<br />

Perhaps I’m a 19th-century astronomer at heart, just outside<br />

absorbing the wonder of the Music of the Spheres!<br />

— Greg Blackman, Adelaide, Australia<br />

Correction<br />

In the February 2016 issue’s “Land of mystery and enchantment,”<br />

p. 35, we misspelled David Blewitt. It should be David<br />

Blewett. — <strong>Astronomy</strong> Editors<br />

URSA<br />

MINOR<br />

1°<br />

using at least a 10-inch telescope<br />

under a dark sky.<br />

PG 1634+706 was brightest<br />

around the year 2000, but is<br />

now nearing its dimmest.<br />

Luckily, PG 1634+706 lies in a<br />

fine field, being only about 7'<br />

southwest of a pair of 8thmagnitude<br />

stars. Furthermore,<br />

this pair lies about 2° northnortheast<br />

of the magnitude 5.0<br />

star 15 Draconis, now culminating<br />

in the north.<br />

Despite my suggested apertures<br />

above, I hate to put a size<br />

limit on what telescope is<br />

needed to see these quasars<br />

(especially PG 1634+706). I<br />

never want to scare off keeneyed<br />

observers who would get a<br />

thrill from snagging this object<br />

through smaller-than-expected<br />

apertures. So fear not and test<br />

the limits of your vision. As<br />

always, let me know how you<br />

do at sjomeara@gmail.com.<br />

18 ASTRONOMY • JUNE 2016