- Page 2 and 3:

Annals of National Institute of Res

- Page 4:

Dear participants to the 17th Trien

- Page 7 and 8:

TRANSCRIPTIONAL PROFILING IN POTATO

- Page 9 and 10:

AGRONOMY...........................

- Page 11 and 12:

Hiltunen L., Virtanen E., Hänninen

- Page 13 and 14:

IN TURKEY - Caliskan M.E ., Caliska

- Page 15 and 16:

IMPROVING THE APPLICATION OF CIPC T

- Page 17:

Key notes

- Page 20 and 21:

Agricultural exploitation type 4 Nu

- Page 22 and 23:

2) Development of clean technologie

- Page 24 and 25:

Box 3. Effects of climate change on

- Page 26 and 27:

glycaemic load (GL) is to be follow

- Page 28 and 29:

Lachman, K. and K. Hamouz: Red and

- Page 30 and 31:

IMPORTANT THREATS IN POTATO PRODUCT

- Page 32 and 33:

3. Control of agrophages during gro

- Page 34 and 35:

DEVELOPMENTS IN POTATO STORAGE IN G

- Page 36 and 37:

temperature and high humidity, ther

- Page 38 and 39:

Fogger Fans controlled by variable

- Page 40 and 41:

POTATO PROCESSING FOR THE CONSUMER:

- Page 42 and 43:

The total number of cultivars, bred

- Page 44 and 45:

al., 1991). We also obtained first

- Page 46 and 47:

transmission into tubers are determ

- Page 48 and 49:

Original seeds, produced on the bas

- Page 50 and 51:

Genetic Modification As state above

- Page 52 and 53:

(2x) with two groups Yari and Ajawi

- Page 54 and 55:

Alexandra Parma Cook and Noble Davi

- Page 56 and 57:

also present in all other yellow fl

- Page 58 and 59:

Potato has acquired a status of a m

- Page 60 and 61:

- Sensitivity to N, which means tha

- Page 62 and 63:

to be present or imminent. Referenc

- Page 64 and 65:

This example characterises the diff

- Page 66 and 67:

PHYSIOLOGY OF THE POTATO: NEW INSIG

- Page 68 and 69:

Iwama, K. 1998. Development of noda

- Page 71 and 72:

Genomics EPITOPES OF THE POTATO VIR

- Page 73 and 74:

identify early cold-responsive gene

- Page 75 and 76:

The GeneChip-assisted qPCR dataset

- Page 77 and 78:

QTLs and markers were projected bas

- Page 79 and 80:

GISH AND FISH ANALYSES OF TETRAPLOI

- Page 81 and 82:

This is the first study applying GI

- Page 83 and 84:

Molecular Breeding INHERITANCE OF R

- Page 85 and 86:

Table 1. Segregation ratios of resi

- Page 87 and 88:

original somatic hybrid; these char

- Page 89 and 90:

ABIOTIC STRESS RESPONSES IN POTATO:

- Page 91 and 92:

EFFECTOR GENOMICS AND CISGENIC EXPL

- Page 93 and 94:

GENOTYPING AND PHENOTYPING OF SOLAN

- Page 95 and 96:

THE EXPRESSION OF Y-VIRUS RESISTANC

- Page 97 and 98:

esistant lines (figure 1, lines b2,

- Page 99 and 100:

COMBINING MARKER ASSISTED SELECTION

- Page 101 and 102:

irdcherry oat aphid Rhopalosiphum p

- Page 103 and 104:

TESTS OF TAXONOMIC AND BIOGEOGRAPHI

- Page 105 and 106:

Since both studies considered resis

- Page 107 and 108:

GENETIC ANALYSIS OF SENSORY AND VOL

- Page 109 and 110:

POTATO BREEDING IN BELARUS: OBJECTI

- Page 111 and 112:

RESISTANCE BREEDING AGAINST PHYTOPH

- Page 113 and 114:

Varietal assessment THE VALORISATIO

- Page 115 and 116:

References - Brescia, M.A., M. Monf

- Page 117 and 118:

VARIATION OF GROWTH AND DISEASE CHA

- Page 119 and 120:

over years and in different countri

- Page 121 and 122:

Table 1. Drought influence on yield

- Page 123 and 124:

IN VITRO SCREENING OF POTATO AGAINS

- Page 125 and 126:

Table 1. Effect of different media

- Page 127 and 128:

Virology EFFECTIVENESS OF PARAFFINI

- Page 129 and 130:

-1998-1999-2000: paraffinic mineral

- Page 131 and 132:

Fig 2. Trial 1998/2000: treatment e

- Page 133 and 134:

3. 2001 trial. 3.1 Treatments effic

- Page 135 and 136:

DETECTION AND MANAGEMENT OF TOBACCO

- Page 137 and 138:

Since 1995, 95% of the sever virus

- Page 139 and 140:

100 80 60 40 20 0 healthy N 605 123

- Page 141 and 142:

were conducted in both Washington S

- Page 143 and 144:

Table 3. Potato plants with zebra c

- Page 145 and 146:

Girsova, N., Bottner, K.D., Mozhaev

- Page 147 and 148:

at 50°C and the inoculated medium

- Page 149 and 150:

3. Pathogenicity tests At the end o

- Page 151 and 152:

Non-wounded tubers rarely had dryco

- Page 153 and 154:

FUSARIUM GRAMINEARUM AS A CAUSE OF

- Page 155 and 156:

indices in comparison with control

- Page 157 and 158:

on leaves. Experimental and trainin

- Page 159 and 160:

ASPECTS IN PATHOGENICITY OF COLLETO

- Page 161 and 162:

was dried at 40°C and stored dry a

- Page 163 and 164:

DETECTION OF SYMPTOMLESS INFECTIONS

- Page 165 and 166:

The CelA PCR primers also did not d

- Page 167 and 168:

BIOLOGIZED SYSTEM OF EARLY POTATO P

- Page 169 and 170: Table 3 Tuber quality of early pota

- Page 171 and 172: EFFECTS OF INTERACTIONS BETWEEN TWO

- Page 173 and 174: Phytophthora EVOLUTION OF THE POPUL

- Page 175 and 176: etween 18°C to 22°C) were good ex

- Page 177 and 178: Fig. 3. : Mefenoxam resistance fiel

- Page 179 and 180: Table 3 : The epidemics in 2004, 20

- Page 181 and 182: protocols of Goodwin et al. (1995).

- Page 183 and 184: PHENOTYPIC TRAITS OF PHYTOPHTHORA I

- Page 185 and 186: % of isolates 100 80 60 40 20 0 R1

- Page 187 and 188: ANALYSIS OF GENETIC VARIABILITY BY

- Page 189 and 190: succeeding the conversion of RAPD m

- Page 191 and 192: Potato seed production IN VITRO BAS

- Page 193 and 194: farm model calculations that relies

- Page 195 and 196: Production costs, ¢/kg 400,00 350,

- Page 197 and 198: STUDIES ON DEVELOPMENT OF NATIONAL

- Page 199 and 200: greenhouses at two institutes in Ma

- Page 201 and 202: produce minitubers from their own v

- Page 203 and 204: Potato Health Management. APS Press

- Page 205 and 206: Figure 2: Average daily temperature

- Page 207 and 208: STUDY THE POTATO - WEED INTERACTION

- Page 209 and 210: Diseases Research Institute (PPDRI)

- Page 211 and 212: 1985a). But, for redroot pigweed, t

- Page 213 and 214: Weed Management. Agricultural Syste

- Page 215 and 216: Table 1Productivity of early variet

- Page 217 and 218: REDUCING COSTS CAUSED BY ISOLATION

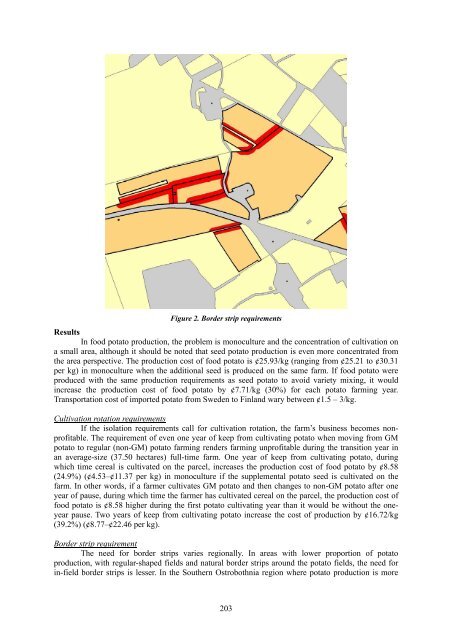

- Page 219: Figure 2. Border strip requirements

- Page 223 and 224: Integrated agrothechnology formatio

- Page 225 and 226: idge planting mineral fertilizers a

- Page 227 and 228: as the colour of crisps and the qua

- Page 229 and 230: due to storage, the quality score d

- Page 231 and 232: CULTIVATION AND ANALYSIS OF ANTHOCY

- Page 233 and 234: anthocyanin content in mg/100g dry

- Page 235 and 236: Physiology YIELD AND BIOMASS PARTIT

- Page 237 and 238: summer-autumn cycle (25.0 and 23.0

- Page 239 and 240: PHYSIOLOGIC SUPPORT OF EARLY GROWN

- Page 241 and 242: 5 th level. Potential crop capacity

- Page 243 and 244: REGULATION OF STEROIDAL GLYCOALKALO

- Page 245 and 246: In 2005 the concentration of Ca and

- Page 247 and 248: ESTIMATION OF POTATO PLANT PHYSIOLO

- Page 249 and 250: Table 3. Mean macro and microelemen

- Page 251 and 252: Tab. 1: Dry matter and sugar conten

- Page 253 and 254: ULTRASOUND IMPROVES CHIP COLOUR OF

- Page 255 and 256: L value 70 60 50 40 Norin 1 M ay Q

- Page 257 and 258: ethereal oils on weight losses were

- Page 259 and 260: After the application, the rains we

- Page 261 and 262: t/ha (35+) to +3,5 t/ha (50+) (figu

- Page 263 and 264: conveyor of both tubers and stones

- Page 265 and 266: shock absorbing units [4]. The dama

- Page 267 and 268: 251 Posters

- Page 269 and 270: AGRONOMY RADIATION USE EFFICIENCY A

- Page 271 and 272:

Field Crops Res. 34, 273-301. Khura

- Page 273 and 274:

Table 1 - Total seasonal water inpu

- Page 275 and 276:

tuber production due largely to red

- Page 277 and 278:

SPAD readings 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 p

- Page 279 and 280:

Table 1. Variants of pre-emergent h

- Page 281 and 282:

THE INFLUENCE OF SELENIUM FERTILIZA

- Page 283 and 284:

Fig 1: Influence of Se-treatment on

- Page 285 and 286:

POTATO CROP ESTABLISHMENT WITH USIN

- Page 287 and 288:

application (Maidl et al., 2002; Pi

- Page 289 and 290:

GENOTOXIC EFFECTS OF EXTRACTS FROM

- Page 291 and 292:

ECOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF FERTILIZERS A

- Page 293 and 294:

magnesium). In soils with the neutr

- Page 295 and 296:

RESULTS OF USING DRIP IRRIGATION FO

- Page 297 and 298:

variety) to 52.3 cm (Futura variety

- Page 299 and 300:

Table 1. Microelements and varietie

- Page 301 and 302:

CONCLUSIONS - applications with Mn

- Page 303 and 304:

Results CLIMATE Figure 1. Climatic

- Page 305 and 306:

Prod. (t/ha) 50,0 Prod. (t/ha) 45,0

- Page 307 and 308:

difficult to record a definite yiel

- Page 309 and 310:

Fig. 9: Application map of Olešná

- Page 311 and 312:

stem infections on the adjacent Agr

- Page 313 and 314:

POTENTIALS FOR WIREWORM CONTROL IN

- Page 315 and 316:

Table 1. Characteristics of tested

- Page 317 and 318:

BREEDING FOR ORGANIC FARMING: COMPA

- Page 319 and 320:

comparatively higher amount of star

- Page 321 and 322:

POTATO SEED PRODUCTION THE INFLUENC

- Page 323 and 324:

Sitobion avenae (Fabricius) 1 9 7 4

- Page 325 and 326:

THE OVERVIEW OF THE RESEARCH AND AP

- Page 327 and 328:

The multiplication of meristem plan

- Page 329 and 330:

EVALUATION OF MICRO TUBER PRODUCTIO

- Page 331 and 332:

Finally, a planter with a cup syste

- Page 333 and 334:

WINIGER, LUDWIG, and BROUWER (1976)

- Page 335 and 336:

Practically, in this case it can be

- Page 337 and 338:

Tubers were selected and sprouted i

- Page 339 and 340:

References Basky Z. (2002). The rel

- Page 341 and 342:

deep on emaciated earths, earthen /

- Page 343 and 344:

Figure 2. Variation of the total tu

- Page 345 and 346:

from the Republic of Karelia for th

- Page 347 and 348:

Degefu Y., Jokela S., Joki-Tokola E

- Page 349 and 350:

potato, in the percentage of farms

- Page 351 and 352:

EVOLUATION OF ACTUAL SITUATION AND

- Page 353 and 354:

BREEDING DEVELOPING SELECTION CRITE

- Page 355 and 356:

maximum soil cover; d = time from m

- Page 357 and 358:

YEAR 0 40.000 seeds Crossings (glas

- Page 359 and 360:

POTATO BREEDING WITHOUT POTATO VIRU

- Page 361 and 362:

Material and methods Like biologica

- Page 363 and 364:

Figure 3. The proposal system to pr

- Page 365 and 366:

Material and methods In this study

- Page 367 and 368:

DEVELOPMENT OF POTATO BREEDING RESE

- Page 369 and 370:

tonnes/ha. Culinary quality is good

- Page 371 and 372:

„CLAUDIU” NEW POTATO ADVANCED C

- Page 373 and 374:

the precision level of the estimato

- Page 375 and 376:

GENETIC RESOURCES THE EVALUATION OF

- Page 377 and 378:

According to the evaluation method,

- Page 379 and 380:

THE EXPLOITATION OF SOLANUM CARDIOP

- Page 381 and 382:

somatic hybrids was lower than that

- Page 383 and 384:

Some genotypes have combined resist

- Page 385 and 386:

Table 1. Primers used for the ampli

- Page 387 and 388:

The genetic variation within a samp

- Page 389 and 390:

The genetic basis of resistance to

- Page 391 and 392:

COPY NUMBER AND TRANSCRIPTION LEVEL

- Page 393 and 394:

STUDY OF GENETIC VARIATION OF EUROP

- Page 395 and 396:

18 6 441 24.5 13 2 83 6.38 26 9 82

- Page 397 and 398:

Use of SSR-markers made possible lo

- Page 399 and 400:

seedlings originated from the hybri

- Page 401 and 402:

level of somatic hybrids by means o

- Page 403 and 404:

characters were less than 1% in 200

- Page 405 and 406:

ADVANCEMENTS IN THE APPLICATION OF

- Page 407 and 408:

gel-electrophoresis, which makes th

- Page 409 and 410:

Results The results are shown in Ta

- Page 411 and 412:

A BIOCHEMICAL AND MOLECULAR APPROAC

- Page 413 and 414:

THE POTATO PHYSICAL AND SEQUENCE MA

- Page 415 and 416:

(Ashoub et al., 1998). This paper d

- Page 417 and 418:

DNA METHYLATION PATTERNS ASSOCIATED

- Page 419 and 420:

COMMUNITY RESOURCES FOR HIGH THROUG

- Page 421 and 422:

to Phytophthora infestans (late bli

- Page 423 and 424:

species, carbapenem antibiotic prod

- Page 425 and 426:

TRANSGENIC RESEARCH INTROGRESSION I

- Page 427 and 428:

changed in the first sexual progeny

- Page 429 and 430:

STUDY OF AGRONOMICAL CHARACTERS OF

- Page 431 and 432:

With respect to mean tuber yield pe

- Page 433 and 434:

THE TRANSGENE CODING FOR THE COLD-I

- Page 435 and 436:

UNRAVELLING STARCH GRANULE MORPHOLO

- Page 437 and 438:

• The seed pool increase. Further

- Page 439 and 440:

MICROTUBERIZATION AS AN EFFICIENT W

- Page 441 and 442:

Table 1. Precipitation (mm) during

- Page 443 and 444:

‘Maret’, ‘Reet’ and breed 1

- Page 445 and 446:

Table 1. Yield performance of potat

- Page 447 and 448:

Table 2. Overall yield performance

- Page 449 and 450:

RESULTS OBTAINED TO SOME POTATO VAR

- Page 451 and 452:

The number of days from emergency t

- Page 453 and 454:

Physical measurements Flesh colour

- Page 455 and 456:

Cultivation site Table 2. Product e

- Page 457 and 458:

PHYSIOLOGY THE INFLUENCE OF THERMAL

- Page 459 and 460:

TS and TO variant (Table 2). By tha

- Page 461 and 462:

INFLUENCE OF VARIOUS FERITLIZATION

- Page 463 and 464:

References (1) Al-Saikhan, M.S. - H

- Page 465 and 466:

EFFECT OF LOCALITY AND VARIETY ON T

- Page 467 and 468:

significant to 21,00 %). On average

- Page 469 and 470:

ECOPHYSIOLOGICAL RESPONSE OF POTATO

- Page 471 and 472:

valid in detecting differences in p

- Page 473 and 474:

FERRIC REDUCING- ANTIOXIDANT POWER

- Page 475 and 476:

References Pawelzik E. Haase N. U.

- Page 477 and 478:

In fenofaza of flowery ( the June)

- Page 479 and 480:

PATHOLOGY VERTICILLIUM WILT OF POTA

- Page 481 and 482:

EVALUATION OF THE DIFFERENT MILDIU

- Page 483 and 484:

Crop emergence (% of seed tubers) 1

- Page 485 and 486:

BIOFUMIGATION FOR REDUCING SOILBORN

- Page 487 and 488:

the fungus appear much faster than

- Page 489 and 490:

drain into the inter-rows. For dise

- Page 491 and 492:

CHLORANTRANILIPROLE (RYNAXYPYR®, C

- Page 493 and 494:

Figure 3. Efficacy on L. decemlinea

- Page 495 and 496:

BIOFUMIGATION FOR CONTROLLING SOIL

- Page 497 and 498:

2007, followed by a further 15 line

- Page 499 and 500:

Jeffries CJ (2001) A history of pot

- Page 501 and 502:

POTATO LATE BLIGHT DISEASE: MECHANI

- Page 503 and 504:

RESULTS In 2006, infection develope

- Page 505 and 506:

EXPLOITATION OF WILD AND INTERSPECI

- Page 507 and 508:

Acknowledgements This work was supp

- Page 509 and 510:

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION Table2. Late

- Page 511 and 512:

The frequency of tubers with late b

- Page 513 and 514:

BACTERIAL DESEASES FATE OF SOIL INF

- Page 515 and 516:

Strips : 1 2 3 4 5 6 June 2002 Sept

- Page 517 and 518:

NEMATODES COMMERCIAL AND TECHNICAL

- Page 519 and 520:

INSECTS POTATO PLANT ACCEPTANCE BY

- Page 521 and 522:

TECHNICAL AND PHYSICAL PARAMETERS M

- Page 523 and 524:

MECHANISATION MECHANIZATION LEVEL A

- Page 525 and 526:

which have been used (though not so

- Page 527 and 528:

TESTING METHOD TO ASSES THE POTATO

- Page 529 and 530:

Fig. 4. The pendulum calibration us

- Page 531 and 532:

AGROTRONICS IN MEASURING AND MAPPIN

- Page 533 and 534:

scientific applications, industrial

- Page 535 and 536:

CONTRIBUTIONS OF THE PRECISION MECH

- Page 537 and 538:

• The substantial increase of the

- Page 539 and 540:

STORAGE STORAGE SUITABILITY OF STAR

- Page 541 and 542:

CARBOHYDRATE METABOLISM OF STARCH P

- Page 543 and 544:

Sugars The sugar contents of all va

- Page 545 and 546:

ASSISTORE - A DECISION SUPPORT SYST

- Page 547 and 548:

Step 3: Application After balancing

- Page 549 and 550:

EFFECTS OF RESTRAIN ON SPROUT GROWT

- Page 551 and 552:

esearch. Data related to the topic

- Page 553 and 554:

½ tea glass of vegetable oil 1 tea

- Page 555 and 556:

Tab. 3: Quality parameter of chippi

- Page 557 and 558:

dumplings of commercial origin was

- Page 559 and 560:

Tab. 2 - Qualitative and technologi

- Page 561 and 562:

EVALUATION OF FLESH COLORED VARIETI

- Page 563 and 564:

Conclusions In total 25 varieties w

- Page 565 and 566:

assimilates to the growing tubers a

- Page 567 and 568:

VIROLOGY THE STRUCTURE, ABUNDANCE,

- Page 569 and 570:

same classes. In 2002, in spite of

- Page 571 and 572:

MANAGEMENT OF POTATO VIRUS Y IN SEE

- Page 573 and 574:

SOIL-BORN VIRUSES IN TATARSTAN Zama

- Page 575 and 576:

Clark and Adams (1977). We used 100

- Page 577 and 578:

The influence of the sample’s inc

- Page 579 and 580:

Potato sprouts of 2 cm, grown on li

- Page 581 and 582:

microtuberisation than Roclas varie

- Page 583 and 584:

Results and Discussion The multipli

- Page 585 and 586:

maximum tuber size, which could be

- Page 587 and 588:

EFFECT OF HAULM APPLICATION OF GIBB

- Page 589 and 590:

Table 2: Weight distribution by cla

- Page 591 and 592:

THE EFFECT OF PHYSIOLOGICAL AGE AND

- Page 593 and 594:

inhibiting roots growth, lateral br

- Page 595 and 596:

Analyzing the obtained data, we obs

- Page 597 and 598:

Conclusions Figure7. Regenerated pl

- Page 599 and 600:

Plants were destructively sampled 1

- Page 601 and 602:

Tuber number per stem 20 15 10 5 0

- Page 603 and 604:

After four weeks of in vitro cultiv

- Page 605 and 606:

vitro growth stage in such a way th

- Page 607 and 608:

STUDY ABOUT POSSIBILITIES OF REPEAT

- Page 609 and 610:

PHYTOPLASMA & ZEBRA CHIP STOLBUR PH

- Page 611 and 612:

POTATO STOLBUR PHYTOPLASMA INDUCED

- Page 613 and 614:

597 Authors index

- Page 615 and 616:

Cooke L.R. ........................

- Page 617 and 618:

Makhan’ko O......................

- Page 619 and 620:

Virtanen E. .......................

- Page 621 and 622:

ADDENDUM EFFECTS OF COMPOST APPLICA

- Page 623 and 624:

Assessments Composts. At the moment