Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

a satisfactory device. He also attempted to symbolize<br />

durational differences by introducing characters of<br />

different widths. However, his system had no better<br />

success than did others of the time.<br />

Languages of America and Africa<br />

In the early 19th century, most of the languages<br />

of Africa and the indigenous languages of America<br />

had no writing systems. Pierre Duponceau (see<br />

Duponceau, Pierre Etienne (1760–1844)), a French<br />

émigré to the United States, won the Volney Prize in<br />

1838 with his Mémoire sur le système grammatical<br />

des langues de quelques nations indiennes de l’Amérique<br />

du Nord, and had shown in an earlier article<br />

(‘English phonology,’ 1817) a thorough understanding<br />

of the principles of a universal alphabet, though<br />

he never produced one himself. Under his influence,<br />

John Pickering (1777–1846), like Duponceau a lawyer<br />

by training, was led to publish his Essay on a<br />

uniform orthography for the Indian languages of<br />

North America (Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1818).<br />

Pickering, like Sir William Jones, whose work he<br />

admired, used a Roman alphabet supplemented by<br />

digraphs and some diacritics, preferring small superscript<br />

letters or subscript numerals to dots or hooks,<br />

which he felt might accidentally be omitted. This<br />

system was designed specifically for Native American<br />

languages, not as a universal alphabet.<br />

Many of the missionary societies were concerned<br />

at this time to establish a standard transcription system.<br />

The Church Missionary Society produced a<br />

pamphlet in 1848 entitled Rules for reducing unwritten<br />

languages to alphabetical writing in Roman characters:<br />

with reference especially to the languages<br />

spoken in Africa. The rules allowed some flexibility<br />

in deciding how detailed the transcription should be,<br />

according to its intended use. The notation suggested<br />

was Roman based, with a few diacritics and some<br />

digraphs. Lewis Grout produced a Roman-based system<br />

for Zulu in 1853, on behalf of the American<br />

Mission in Port Natal, using the symbols <br />

for the clicks.<br />

Carl Richard Lepsius (1810–1884)<br />

In 1852, the Church Missionary Society (CMS) invited<br />

the distinguished German Egyptologist Lepsius to<br />

adapt an alphabet that he had devised earlier, to suit<br />

the needs of the Society. Lepsius had been interested<br />

in writing systems for many years. In 1853, he won<br />

the agreement of the Royal Academy of Berlin to fund<br />

the cutting and casting of type letters for a new alphabet,<br />

to be used as a basis for recording languages with<br />

no writing system. In the following year, an Alphabetical<br />

Conference was convened in London, on the<br />

initiative of the Prussian ambassador in London, Carl<br />

<strong>Phonetic</strong> <strong>Transcription</strong>: <strong>History</strong> 403<br />

Bunsen, who, as a scholar with an interest in philology,<br />

wished to explore the possibility of an agreed<br />

system for representing all languages in writing. The<br />

conference was attended by representatives from the<br />

CMS, the Baptist Missionary Society, the Wesleyan<br />

Missionary Society, and the Asiatic and Ethnological<br />

Societies, and a number of distinguished scholars,<br />

including Lepsius and Friedrich Max Müller. In spite<br />

of their well-known involvement in the transcription<br />

problem, neither Isaac Pitman nor A. J. Ellis was<br />

among those included. Four resolutions were passed:<br />

(1) the new alphabet must have a physiological basis,<br />

(2) it must be limited to the ‘typical’ sounds employed<br />

in human speech, (3) the notation must be rational<br />

and consistent and suited to reading and printing and<br />

also it should be Roman based, supplemented by<br />

various additions, and (4) the resulting alphabet<br />

must form a standard ‘‘to which any other alphabet is<br />

to be referred and from which the distance of each<br />

is to be measured.’’<br />

Lepsius and Max Müller both submitted alphabets<br />

for consideration; Müller’s Missionary alphabet,<br />

which used italic type mixed with roman type, was<br />

not favored, and Lepsius’s extensive use of diacritics<br />

had obvious disadvantages for legibility and the availability<br />

of types. The conference put off a decision,<br />

but later in 1854, the CMS gave its full support to<br />

Lepsius’s alphabet. A German version of the alphabet<br />

appeared in 1854 (Das allgemeine linguistische Alphabet),<br />

followed in 1855 by the first English edition,<br />

entitled Standard alphabet for reducing unwritten<br />

languages and foreign graphic systems to a uniform<br />

orthography in European letters. The Lepsius<br />

alphabet had some success in the first few years, but<br />

Lepsius was pressed by the CMS to produce a new<br />

enlarged edition, which appeared in English in 1863<br />

(printed in Germany, like the first edition, because<br />

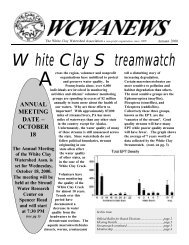

the types were only available there; see Figure 5).<br />

The most obvious difference from the first edition<br />

was that the collection of alphabets, illustrating the<br />

application of Lepsius’s standard alphabet to different<br />

languages, had been expanded from 19 pages and<br />

Figure 5 Symbols of the standard alphabet devised by Lepsius<br />

in 1863.