tessella - the Scientia Review

tessella - the Scientia Review

tessella - the Scientia Review

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Table of Contents<br />

Geometry of Mosaics.......................................................................................3<br />

The Earliest Mosaics......................................................................................4<br />

Case Study: The Antioch Mosaics.................................................................5<br />

Medieval to Modern Mosaics........................................................................6<br />

Case Study: The Ravenna Mosaics...............................................................7<br />

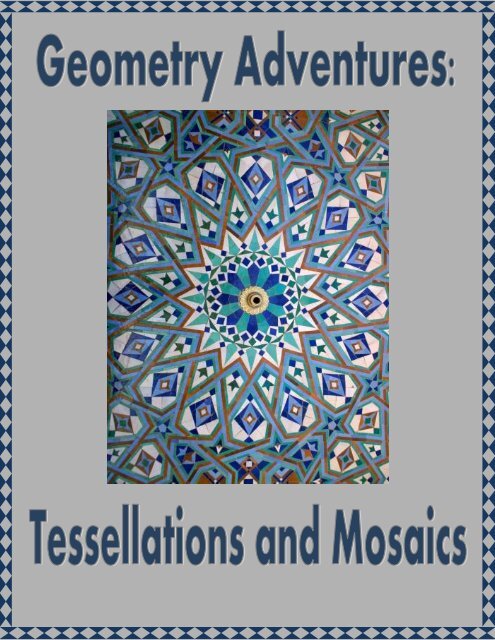

Middle Eastern Mosaics................................................................................8<br />

The Direct Method........................................................................................9<br />

The Indirect Method....................................................................................10<br />

The Double Indirect Method........................................................................11<br />

Case Study: Sonia King...............................................................................12<br />

What are Tessellations?................................................................................13<br />

Regular and Semi-Regular Tessellations.....................................................14<br />

Tessellations in Nature................................................................................15<br />

Case Study: M.C. Escher............................................................................16<br />

Wallpaper Groups.......................................................................................17<br />

Case Study: Nikolas Schiller......................................................................18<br />

Make Your Own: The Line Method............................................................19<br />

Make Your Own: The Slice Method...........................................................20<br />

Glossary......................................................................................................21<br />

About <strong>the</strong> Authors......................................................................................22<br />

Illustration Credits......................................................................................23<br />

2

Geometry of Mosaics<br />

Mosaic is an art form that uses small pieces of materials placed next to each<br />

o<strong>the</strong>r to create an image or pattern. The term for each piece of material is<br />

tessera (plural: tesserae). The tesserae can be shaped like squares or be interlocking<br />

shapes like triangles and rectangles. There are many different ways to<br />

arrange <strong>the</strong> tesserae to produce a picture.<br />

Opus <strong>tessella</strong>tum mosaic (3rd century); <strong>the</strong> refers to<br />

<strong>the</strong> mainly vertical rows in <strong>the</strong> main background<br />

behind <strong>the</strong> animal, where tiles are not also aligned<br />

to form horizontal rows.<br />

One way is to use simple rows and columns<br />

of square or rectangular pieces.<br />

The patterns and pictures are <strong>the</strong>n created<br />

by using different colored pieces.<br />

Ano<strong>the</strong>r way of laying <strong>the</strong> tesserae out<br />

is to have <strong>the</strong> tiles follow <strong>the</strong> outline of<br />

a special shape, for example a central<br />

graphic or letters. The tiles can also<br />

overlap to form curvy, twisting patterns.<br />

And sometimes <strong>the</strong> tesserae are<br />

irregularly shaped and so <strong>the</strong>re is not<br />

pattern in how <strong>the</strong>y are laid out. This is<br />

called “crazy paving.”<br />

An example of “crazy paving” by mosaic artist Sonia King<br />

3

The Earliest Mosaics<br />

The earliest known mosaics date back to<br />

3000 B.C. They were made of pieces of<br />

colored shells, stone, and ivory. Excavations<br />

in Iran have discovered <strong>the</strong> first examples<br />

of glazed tiles used in mosaics,<br />

around 1500 B.C. These early mosaics<br />

were made up of random placements of <strong>the</strong><br />

stones and some simple patterns. In Roman<br />

times, geometric patterns became popular<br />

and many buildings had mosaic floors.<br />

It wasn’t until <strong>the</strong> 200 B.C. that mosaics were used to depict images. The minute<br />

tesserae, or <strong>the</strong> small pieces of tile that make up a mosaic, were cut so small that<br />

sometimes <strong>the</strong>y were only a few millimeters in size. These pieces were so small<br />

that artists could imitate paintings. The expansion of <strong>the</strong> Roman Empire brought<br />

<strong>the</strong> popularity of mosaics to <strong>the</strong> corners of <strong>the</strong> globe. As empires rose and fell, mosaics<br />

stayed an important art form. Mosaics were used to depict religious scenes,<br />

everyday life, and geometric patterns. West of Europe mosaics were also very<br />

popular. In Islamic countries mosaics were not used to create images, but instead<br />

<strong>the</strong>y consisted of complex patterns and <strong>tessella</strong>tions.<br />

Roman (left) and Islamic (right) mosaics<br />

4<br />

The gold leaf mosaic on <strong>the</strong> ceiling of <strong>the</strong> Florence Baptistry

Case Study:<br />

Antioch was an ancient city located near modern-day Antakya, Turkey. The<br />

city thrived as a center of trade through <strong>the</strong> second to sixth century A.D. Mosaic<br />

floors were popular with wealthy merchants and because so many lived in<br />

Antioch, hundreds of designs were constructed. Earthquakes destroyed <strong>the</strong><br />

prosperous city in 526 and 528 A.D. and it wasn’t until 1932 that archeological<br />

An example of a geometric mosaic found at Antioch<br />

digs found <strong>the</strong> incredible mosaics of<br />

Antioch. The archeologists expected to<br />

find great monuments and temples, but<br />

instead discovered more than three hundred<br />

mosaic floors. The largest of<br />

which, measuring 20.5 by 23.3 feet, is<br />

called The Worcester Hunt, and is<br />

housed in <strong>the</strong> Worcester Art Museum.<br />

The materials used by <strong>the</strong> artists who created <strong>the</strong> Antioch mosaics were mostly<br />

colored marble and limestone. The designs of <strong>the</strong> mosaics discovered at Antioch<br />

range from realistic images and scenery to geometric patterns.<br />

Part of one of <strong>the</strong> Antioch mosaics located at <strong>the</strong> Worcester Art Museum<br />

5

Medieval to Modern Mosaics<br />

This mosaic made of fur shows <strong>the</strong> emperor Franz Joseph I<br />

of Austria<br />

Eventually, production of mosaics halted,<br />

until <strong>the</strong> 19th century when <strong>the</strong>re was a revival<br />

of interest in mosaics. The Art Nouveau movement<br />

during this time period artists like Antoni<br />

Gaudi and Josep Maria Jujol started using<br />

After <strong>the</strong> fall of <strong>the</strong> Roman Empire, <strong>the</strong><br />

popularity of mosaics also began to decline.<br />

However, during <strong>the</strong> Middle Ages <strong>the</strong><br />

flourishing tile industry helped keep mosaics<br />

alive in churches and abbeys. Often<br />

<strong>the</strong>se religious buildings would be decorated<br />

by tiled patterns on <strong>the</strong> floors and<br />

ceilings. The styles used started to become<br />

less like traditional mosaics, and more<br />

kinds and shapes of tile were used.<br />

found objects to create mosaics. Their most popular work is in Guell Park, where<br />

<strong>the</strong>y used broken tiles and ceramics to cover buildings. Modern mosaics make use<br />

of found objects and recycled pieces of pottery and ceramics to make interesting<br />

patterns and <strong>tessella</strong>tions.<br />

6<br />

An example of curved, interlocking mosaic pieces<br />

Part of <strong>the</strong> groundbreaking mosaic work of Gaudi and Jujol in Guell Park

Case Study:<br />

Ravenna is a city in modern-day Italy that was <strong>the</strong> capital city of <strong>the</strong><br />

Western Roman Empire from 402 until 476. During <strong>the</strong> height of <strong>the</strong> Roman<br />

Empire, Ravenna was a bustling city filled with trade and fine arts. It’s numerous<br />

churches and public buildings became <strong>the</strong> center of late Roman mosaic art.<br />

An example of a great mosaic in Ravenna is <strong>the</strong> Church of San Giovanni Evan-<br />

Roman mosaic found at Calleva Atrebatum in modern-<br />

day England<br />

gelista, which was commissioned by<br />

her in order to fulfill a promise she had<br />

made having lived through a deadly<br />

storm at sea. The mosaic depicted <strong>the</strong><br />

great storm along with portraits of royalty.<br />

We only know <strong>the</strong> mosaic through<br />

Renaissance sources because it was destroyed<br />

in 1569. In <strong>the</strong> 6th century, after<br />

<strong>the</strong> fall of <strong>the</strong> Western Roman Empire,<br />

<strong>the</strong> Ostrogoths produced <strong>the</strong> mosaics<br />

in <strong>the</strong> Arian Baptistry, Baptistry of<br />

Neon, and <strong>the</strong> Archiepiscopal Chapel as<br />

well as many more. When Ravenna was<br />

conquered in 539 A.D. by <strong>the</strong> Byzantine<br />

Empire it became <strong>the</strong> center of<br />

great Christian mosaic works. The mo-<br />

saics in <strong>the</strong> Basilica of San Vitale and <strong>the</strong> Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo<br />

are outstanding examples of Byzantine mosaics. The last of <strong>the</strong> Byzantine mosaics<br />

in Ravenna was commissioned by bishop Reparatus between 673-79 in<br />

<strong>the</strong> Basilica of Sant'Apollinare in Classe.<br />

7

Middle Eastern Mosaics<br />

Islamic mosaics inside <strong>the</strong> Dome of <strong>the</strong> Rock in Palestine<br />

Muslim conquests of <strong>the</strong> eastern provinces of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Byzantine Empire. The design of mosaics<br />

began to include complex geometric patterns<br />

or twisting vines and trees. The most important<br />

early Islamic mosaic work is <strong>the</strong> decoration of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, <strong>the</strong>n capital<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Arab Caliphate. This mosque was<br />

built in 706 A.D. and at one time <strong>the</strong>re were<br />

Golden mosaics in <strong>the</strong> dome of <strong>the</strong> Great Mosque in Corduba<br />

(965-970)<br />

In modern-day Sou<strong>the</strong>rn Arabia, <strong>the</strong><br />

earliest mosaics date back to <strong>the</strong> late 3rd<br />

century. The pre-Islamic cultures in <strong>the</strong>se<br />

areas created mosaics depicted scenes of<br />

animals and people, but designs that<br />

showed representations of people or animals<br />

were prohibited after <strong>the</strong> Arab conquest<br />

and <strong>the</strong> spread of Islam. Islamic architects<br />

used mosaic technique to decorate<br />

religious buildings and palaces after <strong>the</strong><br />

8<br />

An example of an Islamic nature mosaic<br />

more than 200 artisans working.<br />

Because Islam prohibits depictions<br />

of people and animals in<br />

art, Islamic religious mosaics<br />

filled mosques with <strong>the</strong>ir fantastic<br />

geometric patterns. The nonreligious<br />

buildings in <strong>the</strong> Middle<br />

East, however, had many mosaics<br />

showing nature scenes with<br />

animals.

The Direct Method<br />

There are three main techniques for laying out mosaics: <strong>the</strong> direct<br />

method, <strong>the</strong> indirect method and <strong>the</strong> double indirect method. The direct method<br />

of mosaic construction involves directly gluing <strong>the</strong> tesserae onto whatever surface<br />

<strong>the</strong> mosaic will be on. This technique is useful for placing mosaics on<br />

three-dimensional surfaces such as vases. Most mosaics created in <strong>the</strong> medie-<br />

Tool table for ancient roman mosaics a Roman villa in Spain<br />

val and Roman times used this method.<br />

Sometimes <strong>the</strong> tesserae have fallen off<br />

mosaics and you can see <strong>the</strong> underdrawings<br />

which are <strong>the</strong> drawings made<br />

on <strong>the</strong> surface before <strong>the</strong> tiles are<br />

added. The disadvantage of <strong>the</strong> direct<br />

method is that you have to work directly<br />

on <strong>the</strong> surface, which could mean<br />

sitting for days on a floor. The direct<br />

method is not suitable for long-term or<br />

large scale projects but is advantageous<br />

for small projects because it allows a<br />

lot of flexibility in design changes for<br />

<strong>the</strong> artist.<br />

A 'Direct Method' mosaic courtyard made from irregular pebbles and stone strips<br />

9

Indirect Method<br />

The indirect method is used for large mosaic projects where it is impractical to<br />

work on-site. The tesserae are placed face-up on a mesh or sheet with an adhesive<br />

backing in <strong>the</strong> pattern <strong>the</strong>y will appear. The mosaic is <strong>the</strong>n transferred<br />

onto <strong>the</strong> wall, floor, or o<strong>the</strong>r surface. This method is useful for very large projects<br />

like murals. Many artists use this method because it allows <strong>the</strong>m to work<br />

in <strong>the</strong>ir own studios and rework necessary parts without altering <strong>the</strong> entire<br />

work. Also, using <strong>the</strong> indirect method it is possible to maintain a more even<br />

mosaic than using <strong>the</strong> direct method.<br />

An example of a mosaic created using <strong>the</strong> indirect method. This mosaic is in <strong>the</strong> mausoleum of Galla Placidia<br />

10

Double Indirect Method<br />

An example of a mosaic floor created using <strong>the</strong> double indirect method. This specific mosaic was discovered in Israel and<br />

covers more than 600 square feet<br />

The double indirect method is when tesserae are placed face-up on a sheet of<br />

paper (often adhesive-backed paper, sticky plastic or soft lime or putty) as it<br />

will appear when installed. When <strong>the</strong> mosaic is complete, ano<strong>the</strong>r sheet of adhesive<br />

paper is placed on top of it. The piece is <strong>the</strong>n turned over, <strong>the</strong> original<br />

paper is carefully removed, and <strong>the</strong> piece is installed as in <strong>the</strong> indirect method<br />

described above. This allows <strong>the</strong> artist to see <strong>the</strong> work as it is being put toge<strong>the</strong>r.<br />

However, this method is very complex and requires great skill on <strong>the</strong><br />

part of <strong>the</strong> artist to avoid damaging <strong>the</strong> work. Its greatest advantage lies in <strong>the</strong><br />

possibility of <strong>the</strong> operator directly controlling <strong>the</strong> final result of <strong>the</strong> work,<br />

which is important when <strong>the</strong> human figure is involved.<br />

11

Case Study:<br />

Sonia King was born in 1953 and is a well-known mosaic artist. Her work is<br />

displayed across America and <strong>the</strong> world. She uses a variety of materials to create<br />

her mosaics. Most often, she uses rocks and semiprecious stones in geometric<br />

patterns. King’s artwork does not depict images or real life scenes. Instead,<br />

she uses patterns and natural materials to create abstract landscapes.<br />

King creates contemporary, abstract<br />

mosaic art with a complex variety of<br />

tesserae, working with spacing, reflectivity<br />

and texture. Most mosaics are<br />

grouted, which means <strong>the</strong> spaces between<br />

<strong>the</strong> tiles are filled with a type of<br />

cement, but King prefers not to use<br />

grout and instead emphasize shadows<br />

and negative space. Her abstract, mod-<br />

ern mosaics are very different from <strong>the</strong> religious mosaics of <strong>the</strong> Byzantine period,<br />

but are still just as beautiful.<br />

12<br />

Nebula Aqua mosaic by Sonia King<br />

The Nebula Chroma mosaic King created for <strong>the</strong> Children’s Medical Center of Dallas

What are Tessellations? A <strong>tessella</strong>tion is a pattern of figures that fill<br />

a plane with no spaces or gaps. All <strong>tessella</strong>tions<br />

use translational symmetry while<br />

some patterns use translational, rotational,<br />

and reflective symmetry. In total <strong>the</strong>re are<br />

17 different combinations of symmetries<br />

that can be used to create <strong>tessella</strong>tions.<br />

Subcategories of <strong>tessella</strong>tions include regular,<br />

semi-regular, and demi-regular. The<br />

word itself comes from <strong>the</strong> Latin word<br />

An example of a demi-regular <strong>tessella</strong>tion<br />

<strong>tessella</strong> which means “small stone” and also<br />

refers to <strong>the</strong> tiny bits of stone, clay, or glass<br />

that make up mosaics. Used since ancient<br />

times, <strong>tessella</strong>tions remain an important artistic<br />

tool to this day. Modern Artists such as M. C.<br />

Escher and Nikolas Schiller make extensive<br />

use of <strong>tessella</strong>tions in <strong>the</strong>ir artwork.<br />

Part of M. C. Escher’s Metamorphosis II <strong>tessella</strong>tions<br />

13<br />

An example of one of Nikolas Schiller’s <strong>tessella</strong>tions<br />

made from aerial photographs

Regular and Semi-Regular Tessellations<br />

The two major types of <strong>tessella</strong>tions are regular and semi-regular <strong>tessella</strong>tions<br />

both of which use only regular polygons. A series of congruent regular polygons<br />

comprises a regular <strong>tessella</strong>tion, and two types of congruent regular polygons<br />

comprise a semi-regular <strong>tessella</strong>tion. All regular <strong>tessella</strong>tions use only<br />

equilateral triangles, squares, or regular hexagons. These shapes can <strong>tessella</strong>te<br />

by <strong>the</strong>mselves because 360, <strong>the</strong> number<br />

of degrees around a point, is a multiple<br />

of <strong>the</strong>ir interior angle (refer <strong>the</strong> box at<br />

<strong>the</strong> bottom of <strong>the</strong> page) . Because semi<br />

-regular <strong>tessella</strong>tions can use more than<br />

one type of regular polygon <strong>the</strong>re are<br />

eight possible combinations of shapes.<br />

As with regular <strong>tessella</strong>tions, <strong>the</strong> interior<br />

angles of all <strong>the</strong> shapes at a point<br />

types of congruent regular polygons<br />

must add to 360 degrees. Although <strong>the</strong>re<br />

are 18 ways to fit regular polygons around a point, only 8 of <strong>the</strong>se combina-<br />

14<br />

As shown above, semi-regular <strong>tessella</strong>tions use multiple<br />

As shown above, equilateral triangles, squares, and regular hexagons are <strong>the</strong> only three<br />

polygons whose interior angles can add up to 360 degrees. Because of this, <strong>the</strong>y are <strong>the</strong><br />

only three shapes that can be used to make regular <strong>tessella</strong>tions

Tessellations in Nature<br />

A honeycomb is an example of a natural <strong>tessella</strong>tion<br />

Many <strong>tessella</strong>tions occur all around us<br />

in nature. Honeycombs are a great example<br />

of a hexagonal <strong>tessella</strong>tion pattern.<br />

Fruit like raspberries, grapefruit,<br />

oranges, pineapple skin, and limes all<br />

have repeating patterns that can be classified<br />

as <strong>tessella</strong>tions. Animals can also<br />

sport <strong>tessella</strong>tions: snakeskin, tortoise<br />

shells, and fish scales are all interesting<br />

examples of <strong>tessella</strong>tions in nature.<br />

But perhaps <strong>the</strong> most interesting examples are found in <strong>the</strong> Bimini Wall and <strong>the</strong> Giant’s<br />

Causeway. The Bimini Wall is an underwater wall of rock with many right angles.<br />

For many years, it was thought to be part of <strong>the</strong> ancient city of Atlantis. The<br />

Giant’s Causeway is located in Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Ireland and consists of many hexagonal<br />

columns made of basalt, or hardened lava. Both of <strong>the</strong>se geological phenomena are<br />

called “<strong>tessella</strong>ted pavement.” These fascinating rock formations look like <strong>the</strong>y<br />

have been cut into regular hexagons and rectangles, but <strong>the</strong>y are actually naturally<br />

formed, ei<strong>the</strong>r from volcanoes or eroded bedrock. The right angles of <strong>the</strong> Bimini<br />

Wall were created when water<br />

and sand eroded surrounding<br />

rock but left <strong>the</strong> inherent crystal<br />

structure of <strong>the</strong> rock intact.<br />

This is just one of <strong>the</strong> many examples<br />

of <strong>tessella</strong>ted pavement<br />

and o<strong>the</strong>r types of <strong>tessella</strong>tions<br />

in nature.<br />

15<br />

The Bimini Wall

Case Study:<br />

M. C. Escher was a Dutch graphic artist that was famous for <strong>the</strong> <strong>tessella</strong>tions in<br />

his art. Born in 1898, his family lived in Leeuwarden, <strong>the</strong> Ne<strong>the</strong>rlands before<br />

moving to Arnhem. After high school he attended <strong>the</strong> Haarlem School of architecture<br />

and design. After failing to become an architect, Escher decided to<br />

study decorative arts. In 1937, he started to incorporate ma<strong>the</strong>matics into his<br />

Regular Division of <strong>the</strong> Plane III, woodcut, 1957 - 1958.<br />

artwork which consisted mostly of<br />

lithographs and woodcuts. From a paper<br />

by George Polya, Escher learned<br />

about <strong>the</strong> different symmetries used to<br />

create <strong>tessella</strong>tions. His 1936 Regular<br />

Division of <strong>the</strong> Plane work and his<br />

1937 work Metamorphosis I were some<br />

of his first works to make use of <strong>tessella</strong>tions.<br />

In 1958, he published a book<br />

called Regular Division of <strong>the</strong> Plane<br />

that was composed of his previous<br />

works that made use of <strong>tessella</strong>tions.<br />

His final work to use <strong>tessella</strong>tions was<br />

his Metamorphosis III which he made<br />

The concept of this work (Metamorphosis I) is to morph one image into a <strong>tessella</strong>ted pattern, <strong>the</strong>n gradually to alter <strong>the</strong><br />

outlines of that pattern to become an altoge<strong>the</strong>r different image. From left to right, <strong>the</strong> image begins with a depiction of<br />

<strong>the</strong> coastal Italian town of Atrani. The outlines of <strong>the</strong> architecture <strong>the</strong>n morph to a pattern of three dimensional blocks.<br />

These blocks <strong>the</strong>n slowly become a <strong>tessella</strong>ted pattern of cartoon like figures in oriental attire.<br />

16

Wallpaper Groups<br />

Two <strong>tessella</strong>tions are in <strong>the</strong> same wallpaper group if <strong>the</strong>y have <strong>the</strong> exact same<br />

symmetries. This means two <strong>tessella</strong>tions that have <strong>the</strong> same symmetries can<br />

be translated, rotated, and reflected in <strong>the</strong> same way and still produce a <strong>tessella</strong>tion.<br />

Symmetries aren’t always easy to spot because two <strong>tessella</strong>tions can<br />

look different and still be in <strong>the</strong> same wallpaper group.<br />

Yevgraf Fyodorov proved that only 17<br />

wallpaper groups existed in his 1891<br />

book, The symmetry of regular systems<br />

of figures. Some wallpaper groups use<br />

only translations, rotations, and reflection<br />

while o<strong>the</strong>rs use a combination of<br />

<strong>the</strong> three. All possible <strong>tessella</strong>tions belong<br />

to one of <strong>the</strong> 17 wallpaper groups<br />

each consisting of a different combination<br />

of translational, rotational, and reflective<br />

symmetries.<br />

17<br />

Although <strong>the</strong>y appear different, both<br />

<strong>the</strong>se <strong>tessella</strong>tions belong to <strong>the</strong> same<br />

wallpaper group, p4m.

Case Study: Nikolas Schiller<br />

Nickolas Schiller is an artist who uses digital maps as his medium. While attending<br />

George Washington University, Schiller created a blog that showcased<br />

his modified maps. Using existing digital photographs, Schiller creates imaginary<br />

maps that contain <strong>tessella</strong>tions and o<strong>the</strong>r types of ma<strong>the</strong>matically inspired<br />

designs. His <strong>tessella</strong>ted works take <strong>the</strong>ir inspiration from Arab mosaics such as<br />

Great Mosque in sou<strong>the</strong>rn Spain. Many of his images are of government buildings<br />

from <strong>the</strong> area around Washington D.C. The two images below are composed<br />

of repeated images of <strong>the</strong> state house in Madison, Wisconsin and <strong>the</strong><br />

downtown of Montpelier.<br />

18

Make Your Own: The Line Method<br />

1. First draw an equilateral triangle and draw a wavy line down one of <strong>the</strong><br />

sides.<br />

2. Copy this wavy line and rotate it 60 degrees. You should now have two out<br />

of <strong>the</strong> three of <strong>the</strong> sides of <strong>the</strong> tes- sellation drawn.<br />

3. On <strong>the</strong> final side drawn a wavy line from one vertex to <strong>the</strong> midpoint.<br />

4. Copy this line and rotate it 180 degrees around <strong>the</strong> midpoint. Your <strong>tessella</strong>tion<br />

is com- plete.<br />

19

Make Your Own: The Slice Method<br />

1. Start with a square or equilateral triangle<br />

2. Cut out a piece out of one side of <strong>the</strong> shape<br />

3 . Paste this piece onto <strong>the</strong> opposite side of<br />

<strong>the</strong> figure.<br />

20

Glossary<br />

Archaeological digs: excavation sites where remnants of civilizations ancient<br />

Limestone: a sedimentary rock composed of calcium carbonate<br />

Ivory: The dentine from <strong>the</strong> teeth or tusks of elephants used for carvings and mosaics.<br />

Found objects: an object that is used in art that is intended for some o<strong>the</strong>r use.<br />

Tesserae: The individual tiles that make up a mosaics<br />

Underdrawings: drawings done on a surface before <strong>the</strong> mosaic is laid down. This<br />

ensure that <strong>the</strong> tiles are placed properly<br />

Grout: The substance used to fill in <strong>the</strong> cracks between <strong>the</strong> tiles of <strong>the</strong> mosaics<br />

Ostrogoths: An Eastern Germanic tribe that played an important role in <strong>the</strong> fall of<br />

<strong>the</strong> Roman Empire.<br />

Artisans: Skilled craftsmen who create art such as sculptures and mosaics.<br />

Tessellation: a pattern of figures that fill a plane with no spaces or gaps,<br />

Rotational symmetry: The ability of an object to be rotated a certain amount and<br />

still look <strong>the</strong> same.<br />

Translational symmetry: The ability of an object to be translated a certain amount<br />

and still look <strong>the</strong> same<br />

Reflective symmetry: The ability of an object to be reflected across an axis of symmetry<br />

and still appear <strong>the</strong> same.<br />

Regular polygon: A polygon that has angles that are all <strong>the</strong> same measure and sides<br />

that are all <strong>the</strong> same length.<br />

Interior angle: an angle found inside of a polygon.<br />

Wallpaper group: A classification of a <strong>tessella</strong>tion based on its symmetries. There<br />

are 17 wallpaper groups.<br />

Semi-regular <strong>tessella</strong>tion: A <strong>tessella</strong>tion that uses two or more types of regular<br />

polygons.<br />

Regular <strong>tessella</strong>tion: A <strong>tessella</strong>tion that uses a single type of regular polygon.<br />

Lithograph: A printing method that uses a completely smooth stone or metal plate.<br />

21

About <strong>the</strong> Authors<br />

George Slavin grew up in Douglas, Massachusetts and he is currently a student<br />

at <strong>the</strong> Mass Academy of Math and Science. Outside of school he likes to sing,<br />

play piano, and ride his bicycle.<br />

Anna Brill has lived in Maine, and Rhode Island, but currently resides in<br />

Worcester Massachusetts. She is a student at <strong>the</strong> Mass Academy of Math and<br />

Science. Outside of school she likes to sew, knit, bake, and read books.<br />

This is <strong>the</strong>ir first book collaboration and <strong>the</strong>y hope this volume inspires children<br />

to appreciate <strong>the</strong> connection between ma<strong>the</strong>matics and art.<br />

22

Illustration Credits<br />

pg1: http://fineartamerica.com/images-medium/1-traditional-islamic-zeliji-around<br />

-a-water-fountain-ralph-ledergerber.jpg<br />

pg 2: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Escher,_Metamorphosis_II.jpg<br />

pg 4: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Mosa%C3%AFque_d%27Ulysse_et_les_sir%C3%A8nes.jpg<br />

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Florenca133b.jpg<br />

http://www.<strong>the</strong>joyofshards.co.uk/history/index.shtml (multiple images)<br />

pg 5: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Antakya_Arkeoloji_Muzesi_1250287_nevit.jpg<br />

http://www.<strong>the</strong>joyofshards.co.uk/history/modern.shtml (multiple images)<br />

pg 6: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Fur_mosaic_Emperior_Franz_Josef.jpg<br />

pg 7: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Silchester_mosaic.jpg<br />

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Mosaics,_Worcester_Art_Museum_-_IMG_7457.JPG<br />

pg 8: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Cordoba_moschee_innen5_dome.jpg<br />

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Arabischer_Mosaizist_um_735_001.jpg<br />

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Arabischer_Maler_um_690_002.jpg<br />

pg 9: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Ancient_Roman_Mosaics_Villa_Romana_La_Olmeda_021_<br />

Pedrosa_De_La_Vega_-_Salda%C3%B1a_(Palencia).JPG<br />

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Li_Jiang_Guesthouse.jpg<br />

pg 10: http://farm1.static.flickr.com/89/237212229_7b1d7f02d9.jpg<br />

pg 11: http://assets.nydailynews.com/img/2009/07/02/alg_mosaic.jpg<br />

pg 12: http://www.solo-mosaico.org/2009/sonia-king/?lang=en (two images)<br />

pg 13: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Tiling_Semiregular_3-3-4-3-4_Snub_Square.svg<br />

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Tiling_Dual_Semiregular_V3-12-12_Triakis_Triangular.svg<br />

pg 14: http://library.thinkquest.org/16661/simple.of.regular.polygons/regular.1.html<br />

pg 15: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Buckfast_bee.jpg<br />

http://cltblog.com/media/2008/10/charlotte_spheres2-zoom.jpg<br />

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Escher,_Metamorphosis_II.jpg<br />

pg 16: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Regular_Division_of_<strong>the</strong>_Plane<br />

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metamorphosis_I<br />

pg 17: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wallpaper_group<br />

pg 18: www.nikolasschiller.com<br />

pg 19: George Slavin, 2011<br />

pg 20: George Slavin, 2011<br />

23