SPACES June issue_3July16

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

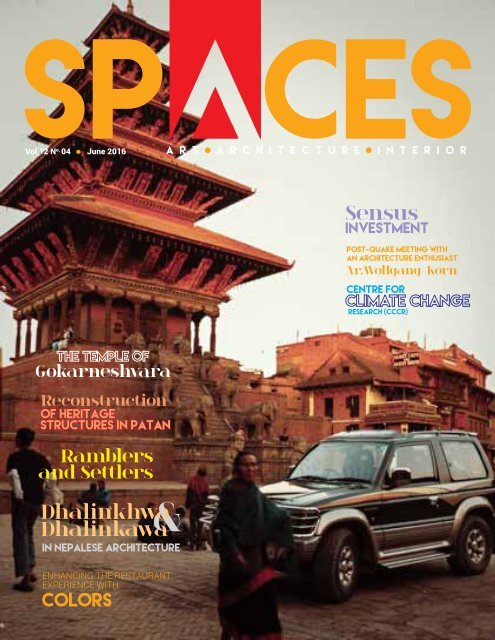

Vol 12 N o. 04 <strong>June</strong> 2016<br />

A R T A R C H I T E C T U R E I N T E R I O R<br />

Sensus<br />

Investment<br />

Post-quake meeting with<br />

an architecture enthusiast<br />

Ar.Wolfgang Korn<br />

CENTRE FOR<br />

RESEARCH (CCCR)<br />

Gokarneshvara<br />

Reconstruction<br />

of heritage<br />

structures in Patan<br />

Ramblers<br />

and Settlers<br />

Dhalinkhwa<br />

&<br />

Dhalinkawa<br />

in Nepalese architecture<br />

Enhancing the Restaurant<br />

Experience with<br />

Colors<br />

<strong>June</strong> 2016 <strong>SPACES</strong> / 1

2 / <strong>SPACES</strong> <strong>June</strong> 2016

HOMESAAZ NEW<br />

<strong>June</strong> 2016 <strong>SPACES</strong> / 3

hxf“ gful/s<br />

Toxf“ gful/s<br />

nagariknews.com<br />

myrepublica.com<br />

4 / <strong>SPACES</strong> <strong>June</strong> 2016

<strong>June</strong> 2016 <strong>SPACES</strong> / 5

Contents<br />

Volume 12 N O. 04 | <strong>June</strong><br />

S P A C E S N E P A L . C O M<br />

54<br />

archAeology<br />

Dhalinkhawas<br />

The use of Dhalinkhawas is a special technique employed by<br />

the Newar architects to give an interesting and appealing took<br />

to the cornice, which in turn beautifies the facade. Sukrasagar<br />

Shrestha explores the details of the craft.<br />

28<br />

interior<br />

Sensus Investment<br />

How can we turn small spaces<br />

into pretty, and a pleasant working<br />

space experience? How can scraps<br />

be used to build beautiful furniture?<br />

Architects are known to employ their ideas to introduce<br />

such innovations. Through this article, you will see how<br />

that can be done.<br />

15<br />

Events<br />

20<br />

archAeology<br />

Interior design competition<br />

An interior designing challenge was organized for students of<br />

the fraternity. It helped enhance the student’s skills and the<br />

ability to find new perspective in things. Pramila Rai tells us<br />

about how the event tried to achieve its purpose.<br />

Ramblers and Settlers<br />

The streets are places for us to roam, to walk, to drive through or to<br />

rest sometimes. Every nook and cranny on the streets serve some<br />

purpose for pedestrians. What have the spaces on the streets in<br />

Kathmandu stood as a significance of? How can these spaces be<br />

used to enhance the aesthetics as well as meet people’s convenience. Here’s on Subik<br />

Shrestha’s take on it.<br />

42<br />

Personality<br />

Discussion with Wolfgang Korn<br />

Nepal lost much of its cultural<br />

heritage during the recent<br />

earthquake. When we’re building<br />

back, what techniques can be<br />

employed to build back better? This article discusses<br />

just that with architecture enthusiast, Ar.Wolfgang Korn.<br />

45<br />

Architecture<br />

JK Cement article<br />

The Centre for Climate Change<br />

Research (CCCR) in Pune,<br />

India, is an example of how a<br />

building can be constructed to<br />

be environmentally friendly, instead in investing the<br />

techniques that take a toll on the atmosphere around<br />

us. The building is a representation of what the<br />

minds at the research centre believe in and stand for.<br />

Madhav Joshi has more for you.<br />

58<br />

interior<br />

Colours article<br />

Colours are vibrant. They can also<br />

be subdued. But what does that<br />

mean for people who experience<br />

the impact of the different shades.<br />

Kritika Rana did some research to tell you how the<br />

colours are used by eateries or bars to have the<br />

desired impact on their visitors.<br />

6 / <strong>SPACES</strong> <strong>June</strong> 2016

<strong>June</strong> 2016 <strong>SPACES</strong> / 7

Volume 12 N O. 04 | june<br />

CEO<br />

Editor-in-Chief<br />

Feature Editor<br />

Director- products and Materials<br />

Creative Manager<br />

Contributing Art Editor<br />

Junior Editor<br />

Correspondent<br />

Advisor<br />

Interns<br />

Contributing Editor<br />

Photographers<br />

Ashesh Rajbansh<br />

Ar. Sarosh Pradhan<br />

Prateebha Tuladhar<br />

Ar. Pravita Shrestha<br />

Deependra Bajracharya<br />

Madan Chitrakar<br />

Kasthamandap Art Studio<br />

Shreya Amatya<br />

Sristi Pradhan<br />

Avantika Gurung<br />

Ar. Pawan Kumar Shrestha<br />

Aastha Subedi<br />

Riki Shrestha<br />

President - Society of Nepalese Architects<br />

Ar. Jinisha Jain (Delhi)<br />

Ar. Chetan Raj Shrestha (Sikkim)<br />

Barun Roy (Darjeeling Hills)<br />

Pradip Ratna Tuladhar<br />

Intl. Correspondent<br />

Director- Operation & Public Relation<br />

Business Development Officer<br />

marketing officer<br />

Accounts<br />

Legal Advisor<br />

Bansri Panday<br />

Anu Rajbansh<br />

Debbie Rana Dangol<br />

Priti Pradhan<br />

Sunil Man Baniya<br />

Yogendra Bhattarai<br />

Distribution<br />

–- Kathmandu –-<br />

Kasthamandap Distributors,<br />

Ph: 4247241<br />

–- Mid & West Nepal –-<br />

Allied Newspaper Distributor Pvt. Ltd.<br />

Kathmandu Ph: 4261948 / 4419466<br />

Published by<br />

IMPRESSIONS Publishing Pvt.Ltd.<br />

Kopundole, Lalitpur, GPO Box No. 7048, Kathmandu, Nepal.<br />

Phone: 5181125, 5181120, info@spacesnepal.com<br />

Design/Layout & Processed at<br />

DigiScan Pre-press Pvt. Ltd.<br />

Advertising and Subscriptions<br />

–- Kathmandu –-<br />

IMPRESSIONS Publishing Pvt.Ltd.<br />

Ph: 5181125, 5181120<br />

market@spacesnepal.com<br />

facebook.com/spacesnepal<br />

twitter.com/spacesnepal<br />

Regd. No 30657/061-62 CDO No. 41<br />

<strong>SPACES</strong> is published twelve times a year at the address above. All rights are reserved in respect of articles, illustrations, photographs, etc. published in <strong>SPACES</strong>. The contents of this publication may not be<br />

reproduced in whole or in part in any form without the written consent of the publisher. The opinions expressed by contributors are not necessarily those of the publisher and the publisher cannot accept<br />

responsiblility for any errors or omissions.<br />

Those submitting manuscripts, photographs, artwork or other materials to <strong>SPACES</strong> for consideration should not send originals unless specifically requested to do so by <strong>SPACES</strong> in writing. Unsolicited manuscripts,<br />

photographs and other submitted material must be accompanied by a self addressed return envelope, postage prepaid. However, <strong>SPACES</strong> is not responsible for unsolicited submissions. All editorial inquiries<br />

and submissions to <strong>SPACES</strong> must be addressed to editor@spacesnepal.com or sent to the address mentioned above.<br />

8 / <strong>SPACES</strong> <strong>June</strong> 2016

Contributors<br />

Niels Gutschow<br />

Dr Niels Gutschow was born in 1941 in Hamburg,<br />

Germany. He is an honorary professor at the<br />

University of Heidelberg, South Asia Institute.<br />

Graduated in architecture from Darmstadt<br />

University, he wrote his PhD-thesis on the<br />

Japanese Castle Town in 1973. From 1978 to<br />

1980 he was head of the Münster Authority of<br />

Monument Protection and from 1980 to 2000 a member of the German<br />

National Committee for Conservation. Now a prolific writer of history<br />

of urban planning in Germany and Europe and into urban space and<br />

rituals in India and Nepal, his book ARCHITECTURE OF THE NEWARS:<br />

A HISTORY OF BUILDING TYPOLOGIES AND DETAILS IN NEPAL (3<br />

VOLUMES) is the most valuable contribution for the documentation and<br />

preservation of Nepali architecture. Currently he lives in Abtsteinach,<br />

Germany and Bhaktapur, Nepal.<br />

Ar. Chandani K.C.<br />

Ar. Chandani K.C. completed Masters of City<br />

and Regional Planning from University of City<br />

and Regional Planning from University of Texas<br />

at Arlington and Bachelors of Architecture from<br />

VNIT, Nagpur. She has worked in numerous<br />

urban planning projects in United States . Her<br />

interest includes urban research and regional<br />

development and she is keen to be involved in<br />

designing cities that are convenient, healthful and<br />

aesthetically pleasing.<br />

Ar. Kritika Rana<br />

Ar.Kritika Rana is a graduate from IOE Pulchowk<br />

Campu. She is currently practicing architecture at<br />

Prabal Thapa Architects. She is keen about research<br />

based writings about architecture and the sensation<br />

of spaces. She believes in understand the essence<br />

of space and its influence in human behavior. She is<br />

also engrossed in energy efficient and sustainable<br />

design in contemporary scenarios.<br />

Shukrasagar<br />

Sukrasagar is an archaeologist and a specialist<br />

in Nepali culture and history. He, coauthoring<br />

with Mehrdad Shokoohy and Natalie H Shokoohy,<br />

has recently published Street Shrines of Kirtipur:<br />

As long as the Sun and Moon Endure (2014).<br />

The book focuses on the shrines’ chronology<br />

from the earliest specimens to the end of the<br />

twentieth century, the reasons for their erection, their typology and<br />

their iconography with the aim of providing a broad understanding of<br />

such features in a wider perspective for all Newar settlements. Another<br />

important he has coauthored is Jarunhiti (2013).<br />

Ar. Sushmita Ranjit<br />

Sushmita Ranjit Shrestha received her B.Arch<br />

degree from IOE. She carries a passion<br />

for contextual writings and art. She has<br />

accomplished various design and construction<br />

projects and is dedicated to her profession.<br />

She is currently working on spatial product<br />

designs alongside consulting for a local product<br />

development and artistic installations design for<br />

MeghauliSerai, a Taj Safaris Lodge at Meghauli.<br />

Subik Kumar Shrestha<br />

Subik Kumar Shrestha is currently working<br />

for the University of Minnesota’s Metropolitan<br />

(Minnesota) Design Center as an Urban Design<br />

Research Fellow. He is pursuing his Ph.D.<br />

in Architecture at the University of Oregon<br />

beginning fall of 2016. Subik aims to improve his<br />

understanding of research and design methods<br />

in sustainable design. He aims to focus on cultural sustainability for<br />

developing a better architectural and urban design language for the<br />

Kathmandu Valley in particular. Subik completed his Master of Science<br />

in Architecture degree (concentrating on Environment Behavior and<br />

Place Studies) from Kansas State University in 2015 and Bachelor of<br />

Architecture from Tribhuvan University in 2011.<br />

Asha Dangol<br />

Asha Dangol is a contemporary Nepali visual<br />

artist. He is co-founder of the Kasthamandap<br />

Art Studio and E-Arts Nepal. He holds Master’s<br />

Degree in Fine Arts from Tribhuvan University,<br />

and has been creating and exhibiting his art<br />

since 1992. He has 10 solo art exhibitions to<br />

his credit. Dangol has participated in numerous<br />

group shows in Nepal and his work has been exhibited in different<br />

countries outside Nepal. The artist experiments with painting, mixed<br />

media, ceramics, installation, performance and video.<br />

Ar. Rumi Singh<br />

Rumi Singh is a B.Arch graduate from IOE<br />

Pulchowk Campus. She is currently working as<br />

an architect in Sustainable Mountain Architecture<br />

(SMA). She has been involved in a Variety of<br />

voluntary works including the Rapid visual<br />

assessment conducted by Nepal Engineering<br />

Association (NEA) post the Nepal Earthquake.<br />

She is also the recipient of the Winning Award at the KVDA Park Design<br />

Competition organized by Society of Nepalese Architects (SONA).<br />

<strong>June</strong> 2016 <strong>SPACES</strong> / 9

editorial<br />

In this <strong>issue</strong> some of the highlights are the viewpoints on construction material, technology and economy in Nepal. As a media<br />

partner for the Nepal BuildCon International and Nepal Wood International Expo 2016, we have taken the opportunity to interview<br />

industrial and business houses that participated at the expo and other business houses. Enclosed is a feature interview on how<br />

businesses have prepared themselves for their journey after the earthquake, the responses from the general public, and opinions on<br />

the construction economy of Nepal.<br />

We also have comments from experts within the construction industry - sharing construction technicalities and management <strong>issue</strong>s<br />

that had been disregarded since decades, along with <strong>issue</strong>s that can be guided towards mitigation. Nepal's construction practices,<br />

if viewed through the lens of the recent 2015 Gorkha Nepal Earthquake, provided a glimpseof the changing construction trends over<br />

the last decade. As Ananta Baidya shares that major aspects of construction practices such as “Public Safety for all including People<br />

with Disabilities and the Elderly” has been disregarded, while vertical growth in infrastructures have sporadically mushroomed all over<br />

Kathmandu Valley. While Badan Nyachhon shares that the last decade has seen positive changes in termsof consulting/utilizing the<br />

services of engineers, architects and designers. There is still plenty that needs to be done, and the bottom line should be not cutting<br />

corners in construction in terms of safety and respecting Mother Nature and the environment.<br />

Conversations on ethics of the built environment – leads us to talk to Ar.Kishore Thapa, the current President of Society of<br />

Nepalese Architect. He shares that the built environment is also the responsibility and moral duty of the citizen, besides the<br />

government rules and regulations. On the note that disciplines of ethics and philosophy should be included in the curriculum of the<br />

architectural schools, he relevantly points out thy architecture students should not only be good architects but should also be good<br />

human beings. Humanities courses are now being included in the engineering curriculum, in order to realize this important aspect.<br />

We also review two interesting events that have sparked a keen interest especially amongst the students - Organic Form making led<br />

by Albert John Mallari and Parametric Environmental Analysis with Saurabh Shrestha. Besides the main objective of the Organic<br />

form-making workshop of playing with the materiality of bamboo and stretchable fabric to create a dimensional form for a luminaire<br />

fixture, the deeper note was perhaps to learn to experiment, play and understand materials and getting beyond the skin to make<br />

meaningful and relevant design. Therein lies the soul of good design, which further echoes the skills of indigenous people are a major<br />

part of the cultural heritage, contributing hugely to the sustainability and design.<br />

We also feature interior designer Preksha Baid’s creatively crafted Ruby Celing at the Park Hotel and Animesh Shrestha’s Architectural<br />

thesis on a modern day Auto Showroom. Besides the interesting Ruby ceiling, what clearly echoes within the features is that it finally is<br />

the awareness and understandings of the designer as well the various people within the context and craft of the design that become tools<br />

for story telling. What does stand out in the design endeavor is to have a sustainable design approach having both innovative as well as a<br />

continuity in treasuring traditional and the skills of our craftsmen.<br />

Much to learn and get inspired further…<br />

Namaste!<br />

Sarosh Pradhan / Editor in Chief<br />

10 / <strong>SPACES</strong> <strong>June</strong> 2016

Technical Associates New<br />

<strong>June</strong> 2016 <strong>SPACES</strong> / 11

12 / <strong>SPACES</strong> <strong>June</strong> 2016

NEPAL CONSTRUCTION MART<br />

THE FIRST CONSTRUCTION<br />

E-COMMERCE STORE IN NEPAL<br />

Value Properties Pvt. Ltd launched www.<br />

nepalconstructionmart.com, Nepal's first<br />

e-commerce store and online information<br />

centre for construction materials on<br />

<strong>June</strong> 12, 2016 - Nepal Construction<br />

Mart. It provides complete e-commerce<br />

solutions to construction materials and<br />

services that give priorities to quality and<br />

customer satisfaction and on time delivery.<br />

Architecture and Engineering Company:<br />

Green Tree Developers, <strong>SPACES</strong> Magazine<br />

and other professional Architects, Engineers<br />

and Builders are amongst the promoters of<br />

Nepal Construction Mart (NCM).<br />

The main objective of NCM is to educate<br />

and empower the customer with the right<br />

information to purchase construction<br />

materials and services and make buying<br />

convenient and easy for them. The<br />

customer can buy various construction<br />

materials and accessories including<br />

Electrical, Sanitary, Plumbing, Interior<br />

Furnishing, Paints, Security System,<br />

Various Building Materials, Doors,<br />

Windows, Household Solutions,<br />

Household Appliances and many more.<br />

The company also provides a wide range<br />

of project solutions for its customers.<br />

The official website www.<br />

nepalconstructionmart.com is a user<br />

friendly and informative website with<br />

the features like handyman tips, buying<br />

guides, material calculator and blogs<br />

providing various construction related<br />

information and updates. To assure that<br />

you don't face problems like low quality or<br />

duplicate products, Nepal Construction Mart<br />

has a precise vendor screening and enlisting<br />

process followed by governing policies set<br />

for vendors to achieve the required product<br />

quality and service levels to ensure your<br />

protection while buying products from us.<br />

They also provide all the necessary building<br />

materials in a package to simplify your<br />

purchases which will not only help you<br />

save money but also help you save time by<br />

avoiding running around to buy different<br />

items multiple number of times from<br />

multiple sources.<br />

NCM'S Protection Measures include:<br />

• Vendor's detailed background check,<br />

including authorization, product quality,<br />

service level agreement etc.<br />

• Buying assistance from our experts so<br />

that you get quality products at best<br />

prices with accurate estimation that suit<br />

your requirements.<br />

• Manufacturer warranty assurance.<br />

• Provision of receipts of your purchase/<br />

payment to assure a legal transaction.<br />

Their prices are very competitive and you<br />

can’t beat their customer service. Even<br />

on a tight time frame Nepal Construction<br />

Mart always comes through for us.<br />

No matter what you need, give Nepal<br />

Construction Mart a call… you won’t be<br />

disappointed!<br />

www.nepalconstructionmart.com<br />

<strong>June</strong> 2016 <strong>SPACES</strong> / 13

e v i e w <br />

G.P. Trading Concern<br />

launches EXCLUSIVE<br />

showroom for Opple<br />

LED Lights<br />

G.P. Trading Concern inaugurated its<br />

EXCLUSIVE store for Opple LED lights<br />

Putalisadak, Kathmandu on April 29, 2016.<br />

G.P. Trading Concern is a successful<br />

trading concern under Triveni Byapar.<br />

Triveni Byapar is the distribution arm of<br />

Triveni group and a well-known business<br />

conglomerate of Nepal. It has been<br />

dealing with some of the most popular<br />

home appliance brands such as Yasuda,<br />

Symphony, Crompton, Panasonic, Sansui,<br />

Samsung etc. The inauguration of the one<br />

of its kind showroom for Opple LED Lights<br />

was done by Mr.Shailesh Sanghai, Company<br />

Director of Triveni Byapar.<br />

The showroom showcases different<br />

varieties of Opple LED Lights available in the<br />

Nepalese Market with features like flicker<br />

free technology and 88% less consumption<br />

of energy than other lighting, which puts<br />

less strain on the eyes and increases<br />

productivity. Opple has a wide range of<br />

lighting products which can cater to an array<br />

of industries, such as hospitality, medical,<br />

commercial and manufacturing. Also,<br />

Opple is the lighting partner for some of<br />

the most renowned businesses around the<br />

world such as Holiday Inn, Adidas Flagship,<br />

Burger King, Starbucks and Sheraton.<br />

Opple provides the most comprehensive<br />

after sales services to consumers in Nepal,<br />

given the much needed quality lighting<br />

required for the Nepalese Market. Knowing<br />

the type of energy deficient country Nepal<br />

is, Opple's saving innovation that reduces<br />

electricity consumption, can solve the<br />

problem to a great extent.<br />

pHofnf] M df]jfOn, cgnfOg / /]l8of]<br />

df]jfOn xftdf, pHofnf] ;fydf<br />

14 / <strong>SPACES</strong> <strong>June</strong> 2016

e v e n t s <br />

INTERIOR DESIGNING COMPETITION ENCOURAGES<br />

STUDENTS TO CHALLENGE THEMSELVES<br />

TEXT : Pramila Rai<br />

T<br />

he functionality of a building depends<br />

in a major way, on appropriate interior<br />

design of the structure. Interior design also<br />

ensures that the structure is aesthetically<br />

pleasing along with its smart functionality.<br />

A first of its kind competition in Nepal, the<br />

national level Interior Design Competition<br />

(IDC) was organized in August 2014,<br />

with the objective of providing a creative<br />

platform for students. This pioneering<br />

initiative of Spaces magazine and Nepal<br />

Furniture and Furnishing Association saw<br />

the participation of 50 students from eight<br />

colleges. IDC 2014 revolved around the<br />

theme of a residential design inspired by<br />

culture but in a modern setting. The designs<br />

were to be submitted in 2D drawing and 3D<br />

computer rendering.<br />

Top 15 students in the final stage of IDC<br />

2014 were given the opportunity to put up<br />

their models for display and public voting at<br />

the Furnex Expo 2014, where a surprisingly<br />

large number of visitors to the furniture<br />

exhibition turned up to vote for their<br />

favorite.<br />

After the successful first attempt, the<br />

organizing committee prepared the second<br />

IDC to be held toward the end of 2015.<br />

Fifty students from IEC College of Art and<br />

Fashion, Kantipur International College<br />

(KIC), Kathmandu Engineering College<br />

(KEC) and Nepal Engineering College<br />

(NEC) joined the contest. Each of the 50<br />

<strong>June</strong> 2016 <strong>SPACES</strong> / 15

e v e n t s <br />

participants had to work on the theme of<br />

a modern BBQ restaurant with a generous<br />

cultural feel to it.<br />

The students were enthusiastic. They<br />

worked hard, did their homework,<br />

researched and learnt. The top three<br />

students assert that the competition was<br />

definitely a learning experience. Lasata<br />

Shrestha from IEC won the top prize for her<br />

project, which had elements of traditional<br />

Newari design and architecture.<br />

“It was just like a real project and we took<br />

the opportunity to learn and research as<br />

best as we could,” she says, recalling the<br />

competition. “I took inspiration from my<br />

own culture and used basic elements of<br />

a typical Newari home with its warm mud<br />

color and wooden posts in the ceiling.”<br />

Shrestha says she worked hard to win and<br />

that managing to do so was a validation of<br />

her hard work.<br />

The competition proved to be the perfect<br />

platform to test the students’ theoretical<br />

knowledge, according to Shrawan Thakuri,<br />

who won the first runner up award. The<br />

KEC student’s project included interesting<br />

ingredients of traditional Nepali art like cobbled<br />

courtyards, stone spouts, and the famous<br />

Durbar Squares. “The contest gave us a<br />

chance to put our learning to practical use.<br />

All the theories and principles we were taught<br />

were finally put into action. We approached it<br />

like a real project,” says Thakuri.<br />

KEC student Pratik Lohani, who won<br />

the second runner up award says the<br />

competition taught him about market<br />

trends, correct budgeting, working on mood<br />

boards, and using the right materials. He<br />

adds that he also learnt the art of interacting<br />

and handling of clients, “I’m an architecture<br />

student, so this was a great opportunity to<br />

learn about interior designing. I worked on<br />

a rustic theme for my BBQ restaurant using<br />

timber and stone in my designs.”<br />

The second IDC had its share of triumphs and<br />

disadvantages. The year 2015 was to be an<br />

eventful year for Nepalis as the country was<br />

first rocked by earthquakes followed by the<br />

Indian border blockade. It can be said that IDC<br />

2015 was an example of the Nepali resilience,<br />

with the organizing committee doing their<br />

best to prepare a great second innings.<br />

Interior architect Sabin Shakya, a member<br />

of the executive committee, believes that<br />

the team did really well despite the barriers.<br />

“The show must go on regardless of what’s<br />

happening,” he says. “So it was tough to<br />

convince sponsors and those directly related<br />

to the competition that we had to keep going.<br />

Given the problems of last year, I think we did<br />

a good job. Of course, there are certain gaps<br />

we have to bridge the next time. But overall, it<br />

was a good collective effort.”<br />

Shakya says lessons for next time includes<br />

being prepared well before hand so as<br />

to avoid last minute rush and decision<br />

making. “It’s also important to educate the<br />

country about the interior design market so<br />

the role of the mainstream media is really<br />

important here,” he says. “This will also<br />

help us connect with clients. Accordingly,<br />

it’s a must to have an effective promotion<br />

package in place, not just IDC but for the<br />

entire interior design industry. Otherwise it<br />

will be a Herculean task to take the industry<br />

to the next level.”<br />

The jury members say that it was quite clear<br />

that students lacked proper grooming. The<br />

panel comprised interior designer, Sabita<br />

16 / <strong>SPACES</strong> <strong>June</strong> 2016

e v e n t s <br />

Sakha, product designer, Pravin Chitrakar,<br />

and architect Sanjaya Pradhan. They<br />

said they observed that the glaring lack<br />

of preparation and guidance stopped the<br />

students from meeting their potential, even<br />

as they were talented.<br />

The judges concur that it is the<br />

responsibility of the colleges to ensure<br />

that their students are prepared for such<br />

competitions. National level competitions<br />

require talent as well as the right kind of<br />

preparations. The jury members said they<br />

felt that the participants lacked proper<br />

guidance and the knowledge required to<br />

excel at such competitions.<br />

At the same time, they were still impressed<br />

by the commitment shown by the<br />

students.<br />

“I appreciated that they worked really<br />

hard and came up with good projects. I<br />

remember we had a hard time selecting<br />

the top five,” Chitrakar recalls.<br />

“A handful of students really caught my<br />

eye, although most of the presentations<br />

needed a lot of improvement,” says<br />

Pradhan, “If they’d been better prepared,<br />

our students would have done really well.<br />

I noticed that students of architecture<br />

focused on architecture in their projects<br />

while interior design students did likewise.”<br />

The minimal interaction opportunity<br />

with participants was another drawback,<br />

according to interior designer Sakha. “We<br />

just had two sessions with them. I believe<br />

with more feedback at different stages,<br />

their final projects could have been a lot<br />

better. Some students did take our advice<br />

which was nice to see,” she adds.<br />

Another suggestion she has for the<br />

organizing committee is to get a superior<br />

filtering process so only the best students<br />

can get in, thus elevating the quality of the<br />

competition.<br />

“The next IDC must be better planned with<br />

each component meticulously thought<br />

out. The organizers should also take in<br />

suggestions and feedbacks from previous<br />

jury members so that it’s better than ever<br />

the next time”, says Pradhan.<br />

Jury members Pradhan and Chitrakar also<br />

said thatthe amount of work expected<br />

from the students and the expectations<br />

were too high.<br />

The jury also commented that the contest<br />

was badly timed with most students<br />

undergoing their final exams, which perhaps<br />

cut into the time they should have used<br />

for project preparations. In spite of the<br />

drawbacks, it is hard to not compliment the<br />

vision of the organizing team.<br />

The judges’ professional backgrounds<br />

came to be a bonus, as their different<br />

professional backgrounds brought fresh<br />

perspective to the event. Students received<br />

different kinds of inputs and advice, which<br />

helped further their knowledge.<br />

According to Pradhan, a competition like this<br />

is important because it gives students the<br />

opportunity to test their own standards.<br />

Chitrakar calls the event successful and adds<br />

that it was a great platform to expose students<br />

to what is expected from them in professional<br />

capacity.<br />

The top three students received cash prizes of<br />

Rs 30,000, Rs 20,000 and Rs 10,000 respectively<br />

along with certificates, trophies, dinner coupons<br />

to BBQ Courtyard restaurant and bar, and coffee<br />

packets from Kathmandu Coffee.<br />

<strong>June</strong> 2016 <strong>SPACES</strong> / 17

e v e n t s <br />

AN<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

TO TIMBER<br />

CONSTRUCTION<br />

Technical Support Office (TSO)<br />

Architectures Sans Frontiers Nepal<br />

(ASFNepal) and Architecture &<br />

Development, supported by Foundation de<br />

France successfully organized a seminar<br />

led by Andrew Lawrence, Associate<br />

Director of Arup, on 'An Introduction to<br />

Timber in Construction'. The workshop was<br />

held at Alliance Françoise, Tripureshwor, on<br />

April 7, 2016.<br />

The workshop had an impressive turnout<br />

of more than a hundred professionals, and<br />

students. His excellency, Yves Carmona,<br />

Ambassador of France to Nepal and<br />

Prafulla Man Singh Pradhan, Advisor at<br />

un habitat were among those attending<br />

the event. The seminar kicked off with an<br />

introductory speech by Pawan Shrestha,<br />

Program Manager of ASF nepal, and his<br />

excellency Yves Carmona talked about the<br />

need to explore different technologies and<br />

ideas, and gave credit to the organizing<br />

team for initiating such programs.<br />

Andrew Lawrence, the timber specialist<br />

from Arup, started off his session with<br />

an argument on why ‘many people<br />

become skeptic about wooden buildings<br />

regarding their durability’. With that said,<br />

he introduced the audience to the oldest<br />

timber building in the UK, that has stood<br />

for oever a thousand years. Lawrence<br />

said that the last 15 years has seen a<br />

renaissance of wooden construction<br />

around the globe, primarily for its<br />

sustainability and durability. He showed<br />

some case studies of houses that were<br />

fully constructed with timber that have had<br />

great results.<br />

Lawrence’s other focus was also on<br />

ensuring maximum resistance against<br />

termite, insects and fungus and its<br />

further treatment using Boron, Pressure<br />

Treatment and other tips, do's and don’ts.<br />

Lawrence reiterated that the locally<br />

found species of timber in Nepal Sal, is<br />

not only very durable but also produces<br />

natural toxins that poisons fungus and<br />

termites. Lawrence concluded his session<br />

supporting his argument with all the<br />

necessary steps that are required for<br />

grooming timber, which is a process worth<br />

the extra mile. Lawrence’s session was<br />

short but precise, informative and helped<br />

build a sense of awareness among the<br />

Nepalese and non-Nepalese, who still live<br />

in timber homes, or are looking towards<br />

building in timber construction.<br />

The talk ended with the floor opening<br />

for questions from the audience.<br />

Questions were raised regarding the use<br />

of materials like bamboo and timber,<br />

policies regarding management of timber<br />

production, structural significance of<br />

traditional joints during the earthquake,<br />

etc. This introductory session on timber<br />

construction left the participants with a fair<br />

knowledge on the topic.<br />

18 / <strong>SPACES</strong> <strong>June</strong> 2016

<strong>June</strong> 2016 <strong>SPACES</strong> / 19

archAeology<br />

Ramblers<br />

and Settlers<br />

Streets as<br />

Determinants of<br />

Urbanism and Urban<br />

Life for Kathmandu<br />

TEXT: Subik Kumar Shrestha<br />

20 / <strong>SPACES</strong> <strong>June</strong> 2016

archAeology<br />

"Streets" in this article refer more to the<br />

pedestrian pathways and sidewalks as parts of<br />

the larger urban movement channels.<br />

In highly cultured urban places (in terms of the quality of<br />

space) around the world, streets form the major urban<br />

open spaces, in contrary to the more conventional<br />

understanding of streets as being solely the arteries that<br />

connect different places or channel movement. Streets<br />

are places themselves that tell the stories of particular<br />

locations—venues where the normal life occurs every day. In<br />

the traditional times, the streets were closely related with the<br />

adjacent buildings through careful ground floor occupation.<br />

The floor immediately in connection with the streets would<br />

have shops and dalans to facilitate and support human flows.<br />

These facilities would be supported by the windows of the<br />

upper floors which maintained direct visual connection with<br />

the streets. In this sense, the houses made a dialogue with<br />

the outdoor environment, most prolifically with the adjacent<br />

streets. Do we find that sociable connection ubiquitously in<br />

Kathmandu today? Simply put, if the answer was a certain yes,<br />

this article would not have been conceived in the first place.<br />

The traditional streets and early modern streets of Kathmandu<br />

possess special characteristics of being able to offer so much<br />

to the urban life, in contrary to the post 2000s contemporary<br />

streets that have been bullying their way all around<br />

Kathmandu till present. The traditional streets possessed<br />

distinct characteristics of being paved in brick or stone and<br />

allowing pedestrian and minimum vehicular access through<br />

the same pathway. This indicates that vehicles requiring<br />

asphalt roads were not in use and more importantly for this<br />

discussion, signifies that a single continuous street system<br />

possibly connected the whole town. The urban design<br />

characteristics of these interlinked continuous streets, thus,<br />

suggest the characteristics of wholeness in urban design<br />

for such towns. It would also mean that pedestrians ruled<br />

the streets and urban spaces, and that lively and vibrant<br />

spaces between buildings existed. While it will be foolhardy<br />

to suggest today that the road/street system should not<br />

promote automobiles, it can certainly be argued that such<br />

road systems should not come in the way of a lively urban<br />

realm. In other words, if major areas of a city contain roads<br />

that prioritize automobiles in place of pedestrians, the urban<br />

and architectural designs will be inclined towards the “auto-<br />

<strong>June</strong> 2016 <strong>SPACES</strong> / 21

archAeology<br />

22 / <strong>SPACES</strong> <strong>June</strong> 2016

archAeology<br />

dominated” cities. Such cities evidently<br />

contain buildings that do not speak with<br />

the outside (e.g., no openings), the ground<br />

floors are usually closed or contain nonsociable<br />

use (lack of retail stores or such<br />

facilities on the ground floor that promotes<br />

interaction), and become deserted (since<br />

there would consequently be fewer reasons<br />

for users to walk).<br />

It is evident that poorly used streets<br />

manifest the urban ills of any place. But<br />

another question needs to be answered as<br />

well: so many of the streets in Kathmandu<br />

are full of moving pedestrians traveling<br />

from one point to the other; so why a<br />

discussion of poorly used streets in terms<br />

of Kathmandu? As an important focus of<br />

this article, it suggests that there are big<br />

differences between ‘traveling pedestrians’<br />

and ‘staying pedestrians.’ In other words,<br />

most of the newer pedestrian streets<br />

in the Kathmandu Valley (the streets in<br />

Baneshwore and Bishal Bazaar along<br />

the ‘institutional’ buildings) are only used<br />

as a medium of movement and not as<br />

“places to stay.”They are treated largely<br />

as channels of movement and supports<br />

no resting (sitting/standing) opportunities<br />

whatsoever to support urban life. Due<br />

to this reason, these pedestrian streets,<br />

although decorated with overcrowding<br />

pedestrian flows, are actually lifeless.<br />

Evidently, one can contend that the<br />

degradation of Kathmandu’s urban street<br />

life, spans a period of more than two<br />

centuries over the Rana era, Shah era,<br />

and Ganatantra (republic) years after that.<br />

Rana period (lasted till 1951) did see some<br />

thoughtful changes made to the street<br />

patterns, particularly with the widening<br />

of road sections for the increasing<br />

automobile use. But these developments<br />

were less sociable in terms of street use<br />

for the pedestrian, except for some visible<br />

examples in the New Road area. Another<br />

fact that needs consideration, however,<br />

is that the Rana rulers at least made<br />

numerous efforts to preserve the street<br />

patterns of the Malla towns and in fact,<br />

contributed large urban fabrics of their<br />

own consisting of such “buildings and<br />

communities that maintain dialogues with<br />

the outside”—a term discussed previously.<br />

This effort should be lauded and was<br />

very important for the Kathmandu Valley<br />

urbanism, although not at equals with the<br />

Malla era urbanism. It was only after the<br />

1950s (the duihajaarsaatsaal ko andolan)<br />

that thoughtful premises for urban<br />

design began lacking from the concerned<br />

authorities, resulting in the present form of<br />

thoughtless street designs.<br />

As an effort to once again bring the<br />

importance of streets in Kathmandu’s<br />

urban design into focus, this article<br />

lists three preliminary characteristics of<br />

streets. It should be noted that this article<br />

is interested in presenting the “design”<br />

aspect more than the “planning” aspect<br />

of the streets. These design qualities and<br />

characteristics present a holistic idea<br />

of understanding and designing streets<br />

as a universal phenomenon for urban<br />

Kathmandu:<br />

1. Architectural design and street life:<br />

a. Building edges and active frontages and<br />

b. Blank walls and the cynical city streets.<br />

2. Streets as stages for manifesting the<br />

urban culture; and<br />

3. Streets as more than channels for<br />

movement.<br />

1. Architectural design and street life<br />

Considering streets as important elements<br />

of urban “design,” the discussion cannot<br />

be considered complete without explaining<br />

their relationship between with the adjacent<br />

buildings. In this regard, two topics become<br />

important: (a) building edges and active<br />

<strong>June</strong> 2016 <strong>SPACES</strong> / 23

archAeology<br />

frontages and (b) blank walls and cynical<br />

architecture.<br />

a. Building edges and active frontages<br />

Building edges and active frontages<br />

play a pivotal role in defining the active<br />

social life of any street. Building edges<br />

represent various opportunities for<br />

passers-by and the public to engage to<br />

the world adjacent to the buildings via<br />

their architectural characteristics. While<br />

the outdoor spaces adjacent to buildings<br />

may be lawns, open spaces, roadways,<br />

or pathways, this discussion focuses on<br />

the role of such building edges which are<br />

adjacent to pedestrian streets. Building<br />

edges are comfortable resting areas<br />

placed on the public side of buildings and<br />

with a direct connection to them, which<br />

influence life between buildings. Some<br />

relevant examples of building edges could<br />

be sittable projections, designed edges,<br />

benches, tiny gardens, shops, or any form<br />

of outdoor seating. If a building contains an<br />

24 / <strong>SPACES</strong> <strong>June</strong> 2016

archAeology<br />

outdoor café with seating, it is making more<br />

connection with the public in the sidewalks<br />

and promotes use. Similar character can be<br />

supposed about shops having displays that<br />

promote window shopping and makes a<br />

connection with the outside.<br />

In specific architectural terms, doors<br />

and windows represent active frontages.<br />

Although this statement reads nothing<br />

that is unheard of, designers vividly<br />

lack the imagination of how to make<br />

proper “urban use” of these elements.<br />

Kathmandu’s fascination with “curtain<br />

walls” is enough of an example to validate<br />

this point. The question of how much does<br />

Kathmandu offer to the citizens through<br />

active frontages may well be answered via<br />

empirical research works and findings, but<br />

a careful observation will certainly indicate<br />

that “doors” and “windows” are slowly<br />

vanishing with the adoption of modern<br />

cultures. There aren’t any governing<br />

rules that require the incorporation of<br />

building elements or facilities at least on<br />

the ground floor that contribute to the<br />

urban congregation while longer stays<br />

in the streets (roadside) of Kathmandu<br />

are turning out to be “urban myths” in so<br />

many of the major locations. Kathmandu<br />

needs more numbers of urban street users<br />

in addition to the ramblers and active<br />

frontages may well play an important role<br />

in attaining this goal.<br />

b. Blank walls and cynical architecture<br />

According to Matthew Carmona, blank<br />

walls are a declaration of “… distrust of the<br />

city and its streets and the undesirables<br />

who might be living inside them.” Blank<br />

walls (both without any openings and<br />

with openings that cannot be actually<br />

opened) are “architectural dead ends” and<br />

long rows of blank frontages (typically<br />

of institutions, banks, corporate offices)<br />

not only deaden the part of the street, but<br />

also break the continuity of experience<br />

vital for the rest of the street. They are<br />

inward focused even if designed in the<br />

best possible way (with fancy court-like<br />

interior spaces), which is not good enough<br />

to bring activity to the streets. It is not<br />

that these buildings individually are an<br />

end in themselves, but blocks after blocks<br />

<strong>June</strong> 2016 <strong>SPACES</strong> / 25

archAeology<br />

of only such institutional<br />

functions without any retail<br />

and residence facilities<br />

are certainly malicious to<br />

urban Kathmandu. One<br />

may walk from the main<br />

road connecting western<br />

end of Tripureshwore with<br />

Teku leading to Kalimati to<br />

observe this phenomenon.<br />

How many are using the<br />

streets in terms of “stays”<br />

than just “walks” in any<br />

given day? Perhaps, only a<br />

handful. People are attracted<br />

to activities which give<br />

opportunities to see, hear,<br />

and meet others. As many<br />

others have noted, people<br />

get attracted only if there<br />

are activities to be involved<br />

in or people to watch. As<br />

this article claims, the street<br />

design should facilitate<br />

the coming together of<br />

individuals; not separating<br />

away from each other.<br />

According to a 2004 TEDtalk<br />

by Howard Kunstler<br />

such huge blank facades<br />

that deliberately disconnects<br />

architecture with urban life<br />

“… make humans feel like<br />

termites,” and rightfully so!<br />

2. Streets as stages for<br />

manifesting the urban<br />

culture<br />

Urban culture in this regard,<br />

refers more, to the dayto-day<br />

activities occurring<br />

on every street in addition<br />

to the special “cultural”<br />

functions they serve (like<br />

jatras and festivals). Whyte<br />

(1980), in a seminal study<br />

of plazas, argued that the<br />

three most important design<br />

factors for plaza design<br />

are: (1) location; (2) streetplaza<br />

relationship; and (3)<br />

seating. Although this article<br />

is not a discussion about<br />

the plaza, Whyte’s findings<br />

and his consideration to<br />

streets as an important<br />

element of urban design<br />

(note the second design<br />

factor) is valuable. This<br />

points to an earlier debate<br />

that streets need to be<br />

connected to each other<br />

and also to other forms of<br />

open spaces, as is evidently<br />

lacking in the Kathmandu<br />

Valley at present. Traditional<br />

Kathmandu Valley streets<br />

are examples of streets<br />

being a stage for all these<br />

activities. Such streets<br />

facilitated not only the dayto-day<br />

urban life but were<br />

designed for the chariot<br />

festivals that would occur<br />

periodically each year.<br />

So, the point that is being<br />

made here is that streets,<br />

in relation with the larger<br />

open spaces are the stages<br />

for urban culture to flourish.<br />

These are the spaces where<br />

city users are allowed to<br />

perform their activities.<br />

Kathmandu needs much<br />

more of such stages, not<br />

less.<br />

One of the more interesting<br />

observations can be noted<br />

from Jane Jacobs’ work in<br />

which the author discusses<br />

‘street ballet’— “…an intricate<br />

ballet in which the individual<br />

dancers and ensembles all<br />

have distinctive parts which<br />

miraculously reinforce<br />

each other and compose<br />

an orderly whole.” Street<br />

ballet can be most clearly<br />

visible in thedaytime in<br />

Asan of Kathmandu. This central node/space has been providing a<br />

platform for urban life for centuries. Even today, one can view flocks of<br />

people passing through this area bearing specific movement of their<br />

bodies and defining the certain flow of mood, that can be correctly<br />

termed as street ballet. One can relate words such as “overcrowding,”<br />

“congestion,” “unmanaged” to the central node of Asan, but the power<br />

of this place should be understood first, more importantly, to learn<br />

from these spaces and to replicate their characteristics in future<br />

designs. Designers who have experienced this phenomenon shall not<br />

attach such disheartening cliché words to indicate Asan.<br />

3. Streets as more than channels for movements<br />

Interesting routes make the “experienced distance” shorter and<br />

promotes walking. Along with the facilities on the ground floor and the<br />

nature of the adjacent buildings, the nature of the streets themselves<br />

26 / <strong>SPACES</strong> <strong>June</strong> 2016

archAeology<br />

can play an important role in fulfilling this<br />

criterion. In connection with the previous<br />

discussions, it becomes important to repeat<br />

here: how does a particular street facilitate<br />

longer stays? Although it is very important<br />

to consider human movement in the design<br />

of streets to facilitate appropriate design<br />

elements, streets and sidewalks need to<br />

be presented as a social arena instead<br />

of being only a channel for an efficient<br />

movement like in modern cities, or as an<br />

aesthetic visual element like in city beautiful<br />

movement. Bill Hillier and Julienne Hanson<br />

(the inventors of space syntax theory) have<br />

advocated that treating urban pathways<br />

and open spaces “…as a place to go and not<br />

to pass through on the way to somewhere<br />

else…” creates the potential for other<br />

activities in addition to the basic activity of<br />

traveling from origin to destination. Major<br />

streets, on the contrary, act as barriers<br />

to longer stays, creating “fragmented”<br />

urban areas because movement if it exists,<br />

becomes only a pass-through activity and<br />

not a social experience.<br />

If one thinks about his/her travel along (1)<br />

the main street from Bhadrakali to Singha<br />

Durbar and (2) along Asan to Indrachowk,<br />

the difference becomes evident. There is<br />

no attraction that makes people stop on<br />

their way to Singha Durbar from Bhadrakali.<br />

The streets there are not vibrant and<br />

people only travel so as to reach other<br />

more bustling places of the city. The main<br />

reason is because the entire strip has been<br />

dedicated to institutions and banks which<br />

do not invite diverse users. Had there been<br />

other primary activities like residences and<br />

stores, the case would have been different.<br />

However, a walk around Asan will give a<br />

different experience to the pedestrians.<br />

Anyone who walks around that path will be<br />

persuaded to stop and look for something<br />

to buy, to enter a religious place, or just look<br />

at the place bustling with activities.<br />

Conclusion<br />

I do not intend to argue that every place<br />

should be packed with people all the<br />

time, but is there harm in making every<br />

pedestrian route in Kathmandu inviting<br />

for longer experience and more exciting?<br />

Can more streets be made a great social<br />

experience and not just a pass-through<br />

way?<br />

<strong>June</strong> 2016 <strong>SPACES</strong> / 27

interior<br />

Sensus<br />

Investment<br />

TEXT : Ar. Rumi Singh Photos : SMA<br />

Swotha stands proud with its historic<br />

temples on the outskirts of the national<br />

heritage, Patan Darbar Square. The studio<br />

for Sensus Investment Company managed<br />

by Reshu Aryal Dhungana is located at the<br />

heart of the old city of Patan. The best part<br />

of this location lies in the fact that no<br />

one can escape the walk through the true<br />

and rich culture of the city before arriving<br />

at the studio. The space originally built in<br />

traditional Newari-style architecture, was<br />

renovated in contemporary design by the<br />

property owner for residential purpose. It<br />

was the joint mission of Sensus Studio and<br />

SMA to transform this apartment based<br />

furnished room into an office space.<br />

T<br />

he wood and bricks gave this small<br />

place a heavy look which is unseemly<br />

for a workplace. This very restriction<br />

became the source for creative inspiration<br />

for this studio designed to exhibit a<br />

personal work zone for Dhakal, with<br />

possibility of a meeting space. The plan<br />

was drawn up as such that the place would<br />

look more work-friendly with the use of<br />

light and colorful materials. A metal based<br />

Thinking Wall and Network Tables and<br />

fabric based Textile Wall were decided to<br />

be placed inside the studio to control the<br />

dark atmosphere, with a conscious use of<br />

materials other than bricks and wood.<br />

Firstly, a space planning was done for<br />

Dhakal’s workplace and a meeting room.<br />

Due to space constraint, innovation had<br />

to come with the design of personal table<br />

and the meeting table, which we call a<br />

Network Table because this is where<br />

the communication takes place. These<br />

tables are made with iron strips generally<br />

considered junk, and painted in seven<br />

different colors. It is topped-off with glass<br />

to provide the sense of tranparency. An<br />

aperture is built at the center of this crosslegged<br />

table through which wires can be<br />

placed in an organized manner. The gaps<br />

between the colorful strips and glass top<br />

provide a complete view of the ceiling to<br />

the floor which creates an illusion of the<br />

space being bigger, brighter and open. Also,<br />

these two equal height tables are designed<br />

to fit each other so that it can be affixed to<br />

be one huge table, to host bigger meetings.<br />

The Thinking Wall has been a solution<br />

of choice for discerning professionals to<br />

place their ideas, notes and memos. And<br />

to spark the ideas and trigger the thinking<br />

process of the visitors and to introduce an<br />

influence of work culture, The Thinking Wall<br />

was what Sensus needed. The blob–shape<br />

was chosen to diffuse the angle of perfect<br />

28 / <strong>SPACES</strong> <strong>June</strong> 2016

interior<br />

geometrical shapes inside the space. It has<br />

a metal frontend so that magnets can be<br />

used to stick papers on to it. Dhakal has<br />

even come up with different materials like<br />

thrown away rubber bands and paper clips<br />

to hold the papers placed on the Thinking<br />

Wall. The offset Textile Wall is hung as<br />

a partition between the kitchenette and<br />

the meeting room. This colorful wall of<br />

2150mm x 1830mm is made out of Nepali<br />

handmade fabric prepared by Women Skill<br />

Development Multi-purpose Cooperative<br />

Ltd. To prevent the movement of the<br />

Textile Wall with the passing of the wind<br />

and to make it sound observant, foam has<br />

Work in progress:<br />

Designers,<br />

Anne Feenstra and<br />

Ruby Singh work<br />

with a craftsman<br />

at designing the<br />

worktable for the<br />

Sensus Investment.<br />

been used. This façade conceals the view<br />

of kitchenette from the outside and also<br />

controls the sound.<br />

The insides of a room influence the<br />

mind. And Sensus Studio, a space of<br />

architectural beauty and iconic design,<br />

is one such exemplary outcome which<br />

believes in investing in heritage but with<br />

contemporary design and fabrication.<br />

The collaboration of Sensus and SMA<br />

focused on acceptance of culture of its<br />

surrounding, brought local artisans and<br />

craftsmen to create cross-cultural design<br />

which helps in composed communication.<br />

Dhakal now proudly opens the door for<br />

her visitors and business partners to her<br />

studio lying just outside of the hustle<br />

bustle of the city.<br />

<strong>June</strong> 2016 <strong>SPACES</strong> / 29

architecture<br />

Gokarneshvara<br />

The apex of the Newar art of woodcarving<br />

at the end of the 16th century<br />

TEXT: Niels Gutschow Photos: Ashesh Rajbansh<br />

30 / <strong>SPACES</strong> <strong>June</strong> 2016

architecture<br />

Nothing is known<br />

about the origin of the<br />

temple. Owing to the<br />

importance of the place<br />

in the myth of creation,<br />

the temple must have<br />

been in existence since<br />

a long time.<br />

<strong>June</strong> 2016 <strong>SPACES</strong> / 31

architecture<br />

Topographical and ritual<br />

context<br />

The Gokarneshvara temple is located<br />

upstream the Bagmati River, marking or<br />

even guarding the first of three gorges the<br />

river makes its way through before leaving<br />

the valley at its southern edge. The name<br />

of the temple refers to a sacred place at the<br />

southwestern coast of India’s Karnataka,<br />

where Shiva is enshrined in the form of the<br />

Atmalinga, the “original” linga. Literally the<br />

“cow’s ear”, the name Gokarna refers to a<br />

myth, according to which Shiva emerged<br />

from the ear of a cow, in front of Brahma<br />

who was about to create the universe. The<br />

creation of replicas of such places is a<br />

common practice in Hinduism and enriches<br />

the sacred landscape of the Kathmandu<br />

Valley in many ways.<br />

The temple of Gokarneshvara in Nepal<br />

figures as the 54th of altogether 64<br />

lingas, arranged in such a way that they<br />

form a spiral-like movement around<br />

the Pashupatinatha, thus arriving at<br />

the spiritual centre of the valley. The<br />

Gokarneshvara also figures as the<br />

second of the Eight Passionless One<br />

(Ashtavaitaraga), which in the Buddhist<br />

tradition of Creation, guard the valley.<br />

Moreover, the temple marks the first of<br />

twelve sacred places (tirtha) along the<br />

Bagmati and Bishnumati, which are visited<br />

by Buddhist devotees along a year-long<br />

pilgrimage (tirthaytara). The place right in<br />

front of the temple is called Punyatirtha<br />

because here, evil (paapa) is given up and<br />

merit (punya) attained. Punyatirtha is the<br />

place to perform a death ritual (shraddha)<br />

in memory of the deceased father on the<br />

day of new moon in September.<br />

One more context needs to be mentioned:<br />

The temple marks the 38th place of a<br />

series of 50 Power Places (Tib. gnas)<br />

identified in the valley according to the<br />

Tibetan tradition, written down in the 1770s<br />

by a Newar monk from the Tibetan “Vulture<br />

Peak Monastery” in Kimdol, at the foot of<br />

Svayambu Hill. This complex configuration<br />

of ritual entanglements presents the<br />

Gokarneshvara temple as a highly<br />

important pilgrimage site, a landmark of<br />

the religious infrastructure of the valley.<br />

History<br />

Nothing is known about the origin of the<br />

temple. Owing to the importance of the<br />

place in the myth of creation, the temple<br />

must have been in existence since a long<br />

time. The early temple was most probably<br />

replaced by the present one at the end of<br />

the 16th century – an inscription at the<br />

pinnacle refers to the year 1583.<br />

Somewhat hidden behind the hill of<br />

Gokarna, the temple has escaped the<br />

attention of historians of the field of<br />

architecture and art. Measuring 9.39 m,<br />

it is slightly larger than the Indreshvara<br />

in Panauti (8.95 m) but smaller than the<br />

Yaksheshvara in Bhaktapur (10.13 m).<br />

While the third tier of the Indreshvara<br />

temple appears to be a later addition<br />

to comply with height ambitions of the<br />

second half of the 17th century, the third<br />

tier of the Gokarneshvara temple seems to<br />

be an integral part of the original design.<br />

With this third roof the temple probably for<br />

the first time overcame the earlier tradition<br />

of the Licchavi era, which survived with the<br />

royal donations of two-tiered temples: the<br />

early 13th century Indreshvara, the 15th<br />

century Yaksheshvara, the three Vaishnava<br />

temples on the Darbar Squares of the<br />

three cities, and the later replicas of the<br />

Pashupatinatha and Changu Narayana.<br />

Later, triple, and even five-tiered temples<br />

with portals replaced earlier ones.<br />

The building<br />

The addition of a third tier is not the only<br />

striking innovation in contrast to the twotiered<br />

structure of those seven temples<br />

mentioned above. Even more innovative<br />

is the fact that the portals were built<br />

without the use of any tympana – the one<br />

facing east is a recent, early 20th-century<br />

addition. Dispensing with the tympana at<br />

portals – maybe the first case in the history<br />

of Newar architecture – also allowed the<br />

builder to abandon the use of the inner<br />

secondary jambs, to which colonnettes<br />

were usually added in order to support a<br />

tympanum.<br />

As a striking result, the four jambs of the<br />

portal are jointly bearing the primary and<br />

secondary lintels. The jambs left and right<br />

of the portal measure 26 by 19.5 cm, those<br />

framing the principal doorway 18 by 16<br />

cm. Compared to the 24 by 20 cm of the<br />

principal jamb of the Yaksheshvara temple,<br />

the dimensions are only slightly larger but<br />

can probably be called more monumental.<br />

The proportions of the Gokarneshvara<br />

temple appear to be more upright.<br />

The portals<br />

The thresholds are made up of three<br />

pieces of roughly dressed stone on all<br />

four sides. The U-shaped intermediate<br />

element dividing the outer frame from the<br />

principal jamb is shaped in a unique way as<br />

a miniature jamb of 10 cm width, with the<br />

bottom end molded in correspondence with<br />

the principal jambs complete with a pot<br />

motif and a narrow niche housing a pair of<br />

anthropomorphic snakes.<br />

The central doorway of rectangular shape<br />

has a stepped frame featuring lotus scrolls.<br />

On the eastern portal the lintel is covered<br />

by gilded copper repoussé. The doorway<br />

itself is framed by a pair of small pillars<br />

which are bearing a lintel with a single<br />

roof-molding. The three-foil cusped arches,<br />

made up of three horizontal layers, feature<br />

wisdom bearers in the spandrels.<br />

The jambs are based on a pot motif<br />

with niches on top with pointed frames,<br />

housing demonic beings usually called in<br />

a very general way daitya. At mid height<br />

medallions with niches are occupied by<br />

female deities playing musical instruments<br />

below a double roof molding and on<br />

top niches with beaded and pointed<br />

frames housing a variety of deities. This<br />

configuration allows 120 deities and<br />

32 / <strong>SPACES</strong> <strong>June</strong> 2016

<strong>June</strong> 2016 <strong>SPACES</strong> / 33

34 / <strong>SPACES</strong> <strong>June</strong> 2016

architecture<br />

demons to be represented. Among these<br />

very few are easily identifiable: a pair of<br />

Surya on the eastern portal, Bhairava and<br />

unnamed demons dominating the southern<br />

portal, Hanuman on the western portal,<br />

Varahi and Kirtimukha on the northern<br />

portal. Bewildering is the use of a group<br />

of creatures with a human body, and<br />

multiple heads of a crow, a cock, peacock,<br />

a ram, and a lion (with horns), and that of a<br />

kneeling female deity holding a scale in the<br />

right hand.<br />

The pointed blocks above the threshold<br />

(bailahkva) are – as is usual for Shaiva<br />

temples – occupied by the Ashtabhairava<br />

in their capacity as guardians of the<br />

universe, the microcosm of which is<br />

represented by the temple. Corresponding<br />

to their specific location in oriented space<br />

we find the Ashtamatrika, the Eight Mother<br />

Goddesses in the quarter-round panels<br />

(dyahkva) of the wall brackets: starting<br />

with Brahmayani on her goose-mount on<br />

the right side of the eastern portal and<br />

ending with Mahalakshmi on her lion on<br />

the left side of the northern portal. Except<br />

Varahi, who appears against a mandorla<br />

and without attendants, all others are<br />

seated on their mounts. They are framed<br />

by attendants with namaskara gesture or<br />

presenting garlands.<br />

Unique and surprising is the group of eight<br />

four-handed male as well as female deities<br />

occupying the wall brackets. The top of<br />

these brackets is invariably occupied by<br />

foliage with up to nine leaves of branches,<br />

populated by birds and monkeys, the<br />

bottom is filled by the aquatic Makara<br />

creature, whose tail develops into three<br />

coils of foliage while the deities either<br />

stand cross legged in its wide opened<br />

jaws (Vishnu, Parvati), or on their mounts<br />

(Durga). The eastern portal is framed on<br />

both sides by female deities, probably<br />

representing Parvati, the southern portal<br />

displays Durga in her form as the crusher of<br />

the buffalo-demon (Mahishasuramardini).<br />

In her upper hands she wields sword and<br />

shield, her lower right hand aims the spear<br />

at the demon in human (right) and even<br />

in elephant form (left). The western portal<br />

presents on the right a rare representation<br />

of Vishnu in his Jalashayana form (“lying<br />

on water”). His head is protected by a fivefold<br />

snake hood, from his navel appears<br />

<strong>June</strong> 2016 <strong>SPACES</strong> / 35

36 / <strong>SPACES</strong> <strong>June</strong> 2016

architecture<br />

right. The deity on the right has a rosary<br />

in her upper right hand, the palm of the<br />

raised left hand supports a bull in miniature<br />

form. Her lower right hand is raised in the<br />

mudra in which the middle finger touches<br />

the thumb, while her lower left hand holds<br />

the noose. Her earrings enclose a snake,<br />

the base of her crown includes skulls. On<br />

her right an ascetic appears offering fruits,<br />

while on her left is a devotee.<br />

Summary<br />

The documentation of the portal’s details<br />

represented something like a revelation<br />

to me and I have no explanation for my<br />

ignorance, not having paid attention<br />

earlier to this outstanding monument of<br />

the Newar architectural tradition. The<br />

carving at Gokarneshvara marks the peak<br />

of artistic achievement and the end of<br />

a period that presented figures with an<br />

outstanding volume. The faces of the Eight<br />

Mother Goddesses and the faces of the<br />

eight deities of the wall brackets are each<br />

crafted in such a way that they overcome<br />

prescriptions or clichés. Individual<br />

characters are created which transcend the<br />

general notion of “deity”. It is rather human<br />

beings with a prominently different facial<br />

features, whom the visitor encounters.<br />

a lotus, which supports the triple-headed<br />

Brahma. On the left side appears again Durga<br />

in her conventional form as the slayer of<br />

the buffalo: her right foot supported by her<br />

regular mount, a lion, her lower left hand<br />

wielding a vajra against the head of the<br />

demon, in this case represented in the form<br />

of a buffalo. The northern portal displays two<br />

forms of Maheshvari, on the left with damaru<br />

and trishul in the upper hands, the lower<br />

hands displaying the varada and abhaya<br />

gestures; her mount, the bull is seen to her<br />

Background<br />

In the context of my ongoing endeavour to<br />

document Newar architecture, details of the<br />

western portal of the Indreshvara temple<br />

in Panauti were presented by <strong>SPACES</strong><br />

in November 2014. In the meantime,<br />

elevations of the portals of ten temples<br />

with an inner ambulatory have been made<br />

by Bijay Basukala at the scale 1:10. The<br />

photographs taken by Ashesh Rajvamsh<br />

are meant to illustrate the drawings the<br />

publication of which, are planned for fall<br />

2016 (Himal, Himalayan Traditions and<br />

Culture Series). The documentation was<br />

supported by the Gerda Henkel Foundation<br />

(Düsseldorf, Germany), a private, non-profit<br />

organization to promote research in the<br />

fields of history, archaeology and history of<br />

art.<br />

<strong>June</strong> 2016 <strong>SPACES</strong> / 37

architecture<br />

Reconstruction<br />

TEXT: :................................<br />

Ar. Chandani KC Photos : Ashesh Rajbansh<br />

38 / <strong>SPACES</strong> <strong>June</strong> 2016

architecture<br />

O<br />

ver the last few years, natural<br />

disasters have caused heavy<br />

losses and damages to human<br />

lives, physical facilities and have affected<br />

socio-economic conditions of different<br />

communities. The tsunami in India, hurricane<br />

in New Orleans, earthquake in Haiti and<br />

floods in Pakistan have completely disrupted<br />

the lives of people and caused damages to<br />

development of the country. The earthquake<br />

of April 25th and May 12th 2015 in Nepal<br />

caused tremendous damages to the buildings<br />

and rendered a staggering loss of lives in 39<br />

districts of Central and Western region of<br />

Nepal. According to the Government of Nepal,<br />

some 6,02,257 houses were destroyed and<br />

1,85,099 damaged. After more than a year<br />

of the earthquake, Nepal is still recovering<br />

from the disaster. Reconstruction process<br />

has been very slow and people are getting<br />

frustrated as their houses and heritage<br />

structures, which are part of their daily lives<br />

have still not been reconstructed. The 2015<br />

earthquakes also caused great devastation<br />

to the heritage structures. According to the<br />

Post Disaster Needs Assessment report, the<br />

earthquakes affected about 2,900 heritage<br />

structures with cultural and religious values.<br />

Major monuments in Kathmandu’s seven<br />

world heritage monument zones were severely<br />

damaged and many collapsed completely.<br />

UNESCO describes it as the greatest loss of<br />

heritage in the last century caused by a natural<br />

disaster. Kathmandu is now slowly reeling<br />

back from the loss of the structures that has<br />

greatly affected the rituals, practices and<br />

activities associated with it.<br />

<strong>June</strong> 2016 <strong>SPACES</strong> / 39

architecture<br />

The<br />

priority in<br />

safeguarding the<br />

materials were wood<br />

rather than the<br />

bricks due to the<br />

craftsmanship<br />

involved.<br />