10 July world supplement

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

2<br />

Monday, july <strong>10</strong>, 2017<br />

DT<br />

Analysis<br />

Insight<br />

3<br />

Monday, july <strong>10</strong>, 2017<br />

DT<br />

The truth behind Qatar-Saudi crisis<br />

• Tribune Desk<br />

During the nearly four decades of<br />

life of their bloc, the Arab states of<br />

the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC)<br />

have failed to attain their ideal of<br />

political consistency and strategic<br />

unity just like their pattern the European<br />

Union.<br />

Such a failure to achieve goal is<br />

apparently observable as the members’<br />

strategic interests conflict and<br />

their political spats show face every<br />

now and then. Their struggle for<br />

seizing leadership of the bloc remains<br />

standing and their national<br />

economies, which are supposed to<br />

be interwoven as a key feature of an<br />

economic union, remain parted.<br />

In the past few years, the deepest<br />

political gap of the six-nation<br />

Arab bloc was caused by differences<br />

between Saudi Arabia and Qatar.<br />

It overshadowed the Arab council’s<br />

all-out potentials, including its political<br />

clout in the regional equations.<br />

The division, additionally, has led to<br />

a polarised GCC, with some member<br />

states such as Bahrain and the UAE<br />

fully supporting Riyadh’s approach<br />

and others like Oman and Kuwait<br />

standing by Qatar that comes against<br />

the unilateral and overbearing policy<br />

of Saudi Arabia.<br />

In past few days, the tensions<br />

set for new escalation as on June<br />

5, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and the<br />

UAE, along with other countries out<br />

of the bloc, severed diplomatic ties<br />

with Doha by recalling ambassadors<br />

and expelling Qatar’s, and also<br />

suspend air, sea and land transport<br />

with Qatar.<br />

The fresh diplomatic spat called<br />

attention of the political analysts,<br />

pushing them to think that Doha is<br />

now on the course to wholly separate<br />

ways from Riyadh.<br />

What are the drives of the new<br />

crisis inside the GCC?<br />

Doha–Riyadh ideological conflict<br />

Although Saudi Arabia and Qatar<br />

are Sunni states they have different<br />

approaches to the sect. In fact,<br />

each one of them wants to apply<br />

and instill across the Muslim and<br />

Arab nations its own interpretation<br />

of the Islamic branch. The Saudi<br />

leadership propagates the Wahhabi<br />

ideology, which develops a narrow-viewed<br />

version of the Islamic<br />

life style. For example, it separates<br />

men and women in public places<br />

and also implements strict sharia<br />

law, allowing tough judicial rulings.<br />

It furthermore, does not recognise<br />

real rights for other sects of Islam.<br />

On the opposite side, Qatar stands<br />

and supports the Muslim Brotherhood<br />

that spreads almost across the<br />

Arab <strong>world</strong>, has a broader view of<br />

the religion, seeks more presence<br />

for the women on the public stage,<br />

and shows more respect for the other<br />

sects of Islam like Shia.<br />

Qatar-Saudi territorial disputes<br />

The rifts over territories between<br />

the two members of the Arab<br />

council have a historical record. In<br />

1992, Doha and Riyadh engaged in<br />

armed border clashes. The kingdom<br />

claimed ownership of 23 miles<br />

of the Qatari south-eastern coasts.<br />

The two neighbours temporarily<br />

reached a deal in 1992 to refer to a<br />

December 1965 border agreement<br />

for de-escalation.<br />

Another dispute point is Khafus<br />

border region. Doha and Riyadh<br />

have failed to settle the case since<br />

1965. The area is crucial for the Qataris<br />

since it links them to the UAE,<br />

their largest trade partner. Riyadh’s<br />

seizure of the area makes all of the<br />

Qatari land roads lead to the Saudi<br />

territory, which means Qatar needs<br />

to pass through Saudi lands to access<br />

the UAE.<br />

Relations with Iran<br />

Another issue standing as a polarising<br />

factor inside the body of the<br />

GCC is the failure by the member<br />

states to adopt a unanimous approach<br />

towards Iran. Saudi Arabia,<br />

spearheading a camp against growing<br />

Iranian influence in the region,<br />

seeks to sever relations between<br />

the GCC and Tehran and has recently<br />

stepped up efforts to build<br />

an anti-Iranian alliance of the Muslim<br />

countries. The recent Riyadh<br />

summit that participated by the US<br />

President Donald Trump echoed<br />

the Saudi anti-Tehran measures.<br />

But Qatar, a country that tries to<br />

adopt an independent policy expand<br />

its influence on the regional<br />

and global stage, has taken a friendly<br />

stance towards Iran.<br />

LIBYA<br />

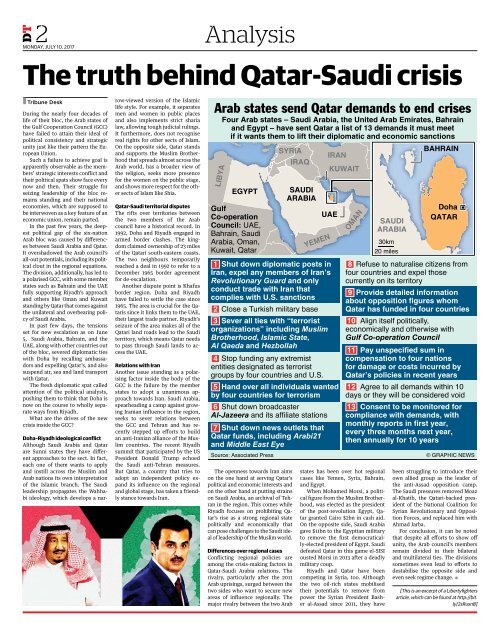

Four Arab states – Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain<br />

and Egypt – have sent Qatar a list of 13 demands it must meet<br />

if it wants them to lift their diplomatic and economic sanctions<br />

EGYPT<br />

Gulf<br />

Co-operation<br />

Council: UAE,<br />

Bahrain, Saudi<br />

Arabia, Oman,<br />

Kuwait, Qatar<br />

Source: Associated Press<br />

The openness towards Iran aims<br />

on the one hand at serving Qatar’s<br />

political and economic interests and<br />

on the other hand at putting strains<br />

on Saudi Arabia, an archival of Tehran<br />

in the region. This comes while<br />

Riyadh focuses on prohibiting Qatar’s<br />

rise as a strong regional state<br />

politically and economically that<br />

can pose challenges to the Saudi ideal<br />

of leadership of the Muslim <strong>world</strong>.<br />

Differences over regional cases<br />

Conflicting regional policies are<br />

among the crisis-making factors in<br />

Qatar-Saudi Arabia relations. The<br />

rivalry, particularly after the 2011<br />

Arab uprisings, surged between the<br />

two sides who want to secure new<br />

areas of influence regionally. The<br />

major rivalry between the two Arab<br />

SYRIA<br />

IRAQ<br />

SAUDI<br />

ARABIA<br />

KUWAIT<br />

UAE<br />

YEMEN<br />

1 Shut down diplomatic posts in<br />

Iran, expel any members of Iran’s<br />

Revolutionary Guard and only<br />

conduct trade with Iran that<br />

complies with U.S. sanctions<br />

2 Close a Turkish military base<br />

3 Sever all ties with “terrorist<br />

organizations” including Muslim<br />

Brotherhood, Islamic State,<br />

Al Qaeda and Hezbollah<br />

IRAN<br />

4 Stop funding any extremist<br />

entities designated as terrorist<br />

groups by four countries and U.S.<br />

5 Hand over all individuals wanted<br />

by four countries for terrorism<br />

6 Shut down broadcaster<br />

Al-Jazeera and its affiliate stations<br />

7 Shut down news outlets that<br />

Qatar funds, including Arabi21<br />

and Middle East Eye<br />

OMAN<br />

states has been over hot regional<br />

cases like Yemen, Syria, Bahrain,<br />

and Egypt.<br />

When Mohamed Morsi, a political<br />

figure from the Muslim Brotherhood,<br />

was elected as the president<br />

of the post-revolution Egypt, Qatar<br />

granted Cairo $2bn in cash aid.<br />

On the opposite side, Saudi Arabia<br />

gave $11bn to the Egyptian military<br />

to remove the first democratically-elected<br />

president of Egypt. Saudi<br />

defeated Qatar in this game el-SISI<br />

ousted Morsi in 2013 after a deadly<br />

military coup.<br />

Riyadh and Qatar have been<br />

competing in Syria, too. Although<br />

the two oil-rich states mobilised<br />

their potentials to remove from<br />

power the Syrian President Basher<br />

al-Assad since 2011, they have<br />

SAUDI<br />

ARABIA<br />

30km<br />

20 miles<br />

BAHRAIN<br />

Doha<br />

QATAR<br />

8 Refuse to naturalise citizens from<br />

four countries and expel those<br />

currently on its territory<br />

9 Provide detailed information<br />

about opposition figures whom<br />

Qatar has funded in four countries<br />

<strong>10</strong> Align itself politically,<br />

economically and otherwise with<br />

Gulf Co-operation Council<br />

11 Pay unspecified sum in<br />

compensation to four nations<br />

for damage or costs incurred by<br />

Qatar’s policies in recent years<br />

12 Agree to all demands within <strong>10</strong><br />

days or they will be considered void<br />

13 Consent to be monitored for<br />

compliance with demands, with<br />

monthly reports in first year,<br />

every three months next year,<br />

then annually for <strong>10</strong> years<br />

© GRAPHIC NEWS<br />

been struggling to introduce their<br />

own allied group as the leader of<br />

the anti-Assad opposition camp.<br />

The Saudi pressures removed Moaz<br />

al-Khatib, the Qatari-backed president<br />

of the National Coalition for<br />

Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition<br />

Forces, and replaced him with<br />

Ahmad Jarba.<br />

For conclusion, it can be noted<br />

that despite all efforts to show off<br />

unity, the Arab council’s members<br />

remain divided in their bilateral<br />

and multilateral ties. The divisions<br />

sometimes even lead to efforts to<br />

destabilise the opposite side and<br />

even seek regime change. •<br />

[This is an excerpt of a Libertyfighters<br />

article, which can be found at http://bit.<br />

ly/2sRusn8]<br />

An image grab taken from a propaganda video released by Islamic State (IS) terrorists group, have shown children training for combat and performing executions<br />

Can Islamic State’s indoctrinated kids be<br />

saved from a future of violent jihad?<br />

• Tribune Desk<br />

The blue-eyed boy with the chubby<br />

cheeks still talks about the after-school<br />

movies he used to love<br />

so much. This was three years ago,<br />

when he was just 9 and living on<br />

the outskirts of Raqqa, in northern<br />

Syria. Sometimes, his father would<br />

take him and his little brother to an<br />

outdoor makeshift theatre. The films<br />

varied, but the plot was always the<br />

same: Black-clad members of the<br />

Islamic State militant group (IS) “liberated”<br />

cities from kuffar, or non-believers,<br />

chopping off their heads in<br />

bloody, righteous celebration. There<br />

was no acting involved. The films<br />

showed real events. “I thought,” the<br />

boy recalls, “it would be fun to go to<br />

jihad.” Today, the boy who asked to<br />

be identified only as Mohammed,<br />

lives with his uncle in the Turkish<br />

town of Reyhanli. When we meet on<br />

a cool evening in May in his uncle’s<br />

tidy but crowded home, I am surprised<br />

to hear that the violence in<br />

those videos never frightened him.<br />

“They are kuffar, and it is OK to kill<br />

them,” he explains. Instead, he recalls<br />

feeling “excited” as he watched<br />

the action on screen or when he<br />

spotted IS fighters patrolling the<br />

streets of Raqqa, enforcing the exacting<br />

dress codes and mosque attendance<br />

mandated by their radical<br />

interpretation of Islamic law.<br />

The drift of Mohammed and his<br />

two brothers toward IS worried his<br />

uncle, who asked to be identified<br />

only as Ra’ed, convinced the boys’<br />

father to move with his family out<br />

of Raqqa, the militant group’s main<br />

stronghold in Syria, and into Turkey.<br />

Today, Ra’ed and his own family<br />

share their home with the three<br />

boys- Mohammed, who is now 12,<br />

<strong>10</strong>-year-old Ibrahim and 16-yearold<br />

Salim and their parents. The<br />

boys are studying in a Unicef-funded<br />

school for Syrian refugees. Hoping<br />

to shift their allegiance away<br />

from violent jihad, Ra’ed bought<br />

them iPads, has them pitch in at<br />

his second-hand clothing shop and<br />

tries to gently challenge their beliefs<br />

about what it means to be a<br />

good Muslim. But even after nine<br />

months away from the jihadi group,<br />

the boys still idolize the soldiers of<br />

the self-styled caliphate. “They are<br />

always yelling at me, ‘Why did you<br />

bring us here?’” Ra’ed says. “It’s going<br />

to take time. A brain is not like a<br />

computer. Once it downloads information,<br />

it cannot easily be erased.”<br />

The propaganda<br />

IS devoted extensive resources to<br />

the indoctrination of children in its<br />

territory, which at its peak, from<br />

mid-2014 through 2015, spanned<br />

roughly a third of Syria and Iraq and<br />

was home to between 6m and 12m<br />

civilians. Swiftly and methodically,<br />

the group forced its curriculum<br />

on schools and lured children to its<br />

training camps with gifts and propaganda<br />

videos. IS also captured the<br />

children of its enemies, from Yazidis<br />

to Christians, and brainwashed<br />

many of them in training camps<br />

before sending them off to battle as<br />

soldiers or suicide bombers. Now, as<br />

US-backed forces in Syria and Iraq<br />

close in on the last IS strongholds,<br />

the <strong>world</strong> is getting an increasingly<br />

detailed look at the damage wrought<br />

on a generation of youth. The first to<br />

grapple with this damage are those<br />

on the outskirts of IS’s collapsing<br />

territory. Interviews with children<br />

now living in southern Turkey and<br />

northern Iraq who attended IS training<br />

camps and schools, as well as<br />

the therapists and security officials<br />

scrambling to assess them, open a<br />

rare window into the crisis.<br />

In addition to being far behind in<br />

their education, many of these children<br />

are suffering from trauma and<br />

other mental health issues. Some of<br />

them also alarm authorities, and,<br />

in some cases, their families, with<br />

their extremist views and violent<br />

behaviour. Liesbeth van der Heide,<br />

an expert on the rehabilitation and<br />

reintegration of terrorists at the International<br />

Centre for Counter-Terrorism<br />

in the Hague, says IS is a<br />

much graver challenge than other<br />

extremist groups that tried to radicalise<br />

communities.<br />

Slow poisoning education<br />

When IS seized control of Mosul,<br />

Iraq, and announced the establishment<br />

of its caliphate in June<br />

2014, Umar Aljbouri was working<br />

there at a government-run institute<br />

for women and children. The<br />

civil servant continued reporting<br />

to work each day as the militants<br />

asserted their control over Mosul’s<br />

nearly 2m inhabitants, one institution<br />

at a time. Eventually, they shut<br />

down his institute and instructed<br />

Aljbouri to begin reporting to a<br />

local elementary school that was<br />

short of teachers. Though Aljbouri<br />

had never taught, he was afraid to<br />

object and agreed to attend mandatory<br />

IS training courses for teachers.<br />

There, he learned that teachers<br />

and children of all ages were to be<br />

separated by gender, and they were<br />

to adhere to a strict Islamic dress<br />

code. Many subjects that had been<br />

taught, including history and literature,<br />

were scrapped; mathematics,<br />

Arabic and the study of Islam would<br />

remain, but only according to IS’s<br />

curriculum. Eventually, the group’s<br />

office of education distributed IS<br />

course materials and textbooks.<br />

“IS’s curriculum was based on<br />

extremist doctrine,” he says. “It was<br />

inviting children to hate and kill<br />

people from other religions. Even in<br />

mathematics, instead of ‘1 apple + 2<br />

apples = 3 apples,’ they would say,<br />

‘1 bullet + 2 bullets = 3 bullets.’ Parents<br />

were so worried.”The education<br />

overhaul was part of a broader<br />

indoctrination for children that IS<br />

instituted in towns and cities across<br />

its territory.<br />

Mohammed Alhamed, an activist<br />

tracking IS education in Syria,<br />

says the group used schools to ease<br />

children into the organisation. “IS<br />

doesn’t force children to join them.<br />

But they teach them their rules and<br />

everything about jihad and the Islamic<br />

State, and by the time they<br />

are older, they want to join.” While<br />

IS threatened parents who wouldn’t<br />

send their children to school with<br />

fines or lashings, it took a lighter approach<br />

with its pupils. Mohammed,<br />

the boy now in Reyhanli, attended<br />

an IS-run school for two years<br />

at a mosque in Raqqa. He says his<br />

teachers never used corporal punishment<br />

and treated students “really<br />

nice. I liked them, and I liked<br />

Islam. They said if you read the Koran,<br />

you get prizes.”<br />

Courtesy: NEWSWEEK<br />

Rehabilitation<br />

There have been small and sporadic<br />

efforts to identify the young ones in<br />

need of aid, but it is easy for parents<br />

to keep these children in the shadows.<br />

Some families who want help<br />

for their radicalised children are reluctant<br />

to seek it, fearing they will<br />

be investigated and punished by<br />

local security services. Others, like<br />

Ra’ed, think they can manage the<br />

problem on their own. The family<br />

patriarch acknowledges that there<br />

have been some missteps in his efforts<br />

to rehabilitate his nephews.<br />

Once, when Salim first arrived<br />

from Raqqa, Ra’ed brought the teen<br />

to a beach to challenge his deeply<br />

conservative views about women.<br />

Upon seeing women in bikinis, Salim<br />

fumed that he should “behead<br />

them and turn the sea red with their<br />

blood.” When Ra’ed bought Ibrahim<br />

an iPad, the boy instantly downloaded<br />

war games. But he believes he is<br />

slowly winning this war of hearts<br />

and young minds. “They are all getting<br />

better,” he insists. “It’s a different<br />

lifestyle here, and bit by bit, they<br />

are changing.” He is less optimistic,<br />

though, about the children of IS sympathisers,<br />

whom he sees from time<br />

to time around Reyhanli. One recently<br />

visited his second-hand clothing<br />

shop. The boy erupted in rage<br />

when his sister approached Ra’ed to<br />

inquire about a size. “Why are you<br />

talking to a man?” he screamed. “If<br />

you have a question, you ask me,<br />

and I ask him. I swear to God, I will<br />

go back home and have your older<br />

brother cut your head off.”As Ra’ed,<br />

recounts the story, he shakes his<br />

head. “Some of these children are<br />

growing up with jihadist ideas. And<br />

they will be a problem for the future<br />

of the whole <strong>world</strong>.” •<br />

[This is an excerpt of a Newsweek<br />

article, which can be found at http://bit.<br />

ly/2swCmhI]