Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

PROFILE<br />

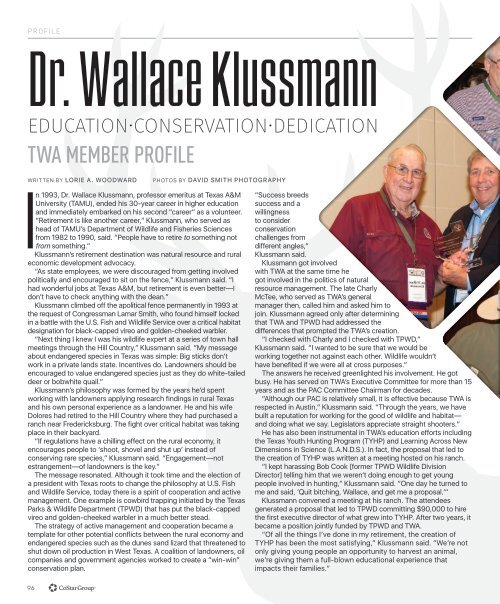

Dr. Wallace Klussmann<br />

EDUCATION•CONSERVATION•DEDICATION<br />

TWA MEMBER PROFILE<br />

WRITTEN BY LORIE A. WOODWARD<br />

PHOTOS BY DAVID SMITH PHOTOGRAPHY<br />

In 1993, Dr. Wallace Klussmann, professor emeritus at Texas A&M<br />

University (TAMU), ended his 30-year career in higher education<br />

and immediately embarked on his second “career” as a volunteer.<br />

“Retirement is like another career,” Klussmann, who served as<br />

head of TAMU’s Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences<br />

from 1982 to 1990, said. “People have to retire to something not<br />

from something.”<br />

Klussmann’s retirement destination was natural resource and rural<br />

economic development advocacy.<br />

“As state employees, we were discouraged from getting involved<br />

politically and encouraged to sit on the fence,” Klussmann said. “I<br />

had wonderful jobs at Texas A&M, but retirement is even better—I<br />

don’t have to check anything with the dean.”<br />

Klussmann climbed off the apolitical fence permanently in 1993 at<br />

the request of Congressman Lamar Smith, who found himself locked<br />

in a battle with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service over a critical habitat<br />

designation for black-capped vireo and golden-cheeked warbler.<br />

“Next thing I knew I was his wildlife expert at a series of town hall<br />

meetings through the Hill Country,” Klussmann said. “My message<br />

about endangered species in Texas was simple: Big sticks don’t<br />

work in a private lands state. Incentives do. Landowners should be<br />

encouraged to value endangered species just as they do white-tailed<br />

deer or bobwhite quail.”<br />

Klussmann’s philosophy was formed by the years he’d spent<br />

working with landowners applying research findings in rural Texas<br />

and his own personal experience as a landowner. He and his wife<br />

Dolores had retired to the Hill Country where they had purchased a<br />

ranch near Fredericksburg. The fight over critical habitat was taking<br />

place in their backyard.<br />

“If regulations have a chilling effect on the rural economy, it<br />

encourages people to ‘shoot, shovel and shut up’ instead of<br />

conserving rare species,” Klussmann said. “Engagement—not<br />

estrangement—of landowners is the key.”<br />

The message resonated. Although it took time and the election of<br />

a president with Texas roots to change the philosophy at U.S. Fish<br />

and Wildlife Service, today there is a spirit of cooperation and active<br />

management. One example is cowbird trapping initiated by the Texas<br />

Parks & Wildlife Department (TPWD) that has put the black-capped<br />

vireo and golden-cheeked warbler in a much better stead.<br />

The strategy of active management and cooperation became a<br />

template for other potential conflicts between the rural economy and<br />

endangered species such as the dunes sand lizard that threatened to<br />

shut down oil production in West Texas. A coalition of landowners, oil<br />

companies and government agencies worked to create a “win-win”<br />

conservation plan.<br />

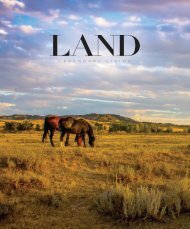

“Success breeds<br />

success and a<br />

willingness<br />

to consider<br />

conservation<br />

challenges from<br />

different angles,”<br />

Klussmann said.<br />

Klussmann got involved<br />

with TWA at the same time he<br />

got involved in the politics of natural<br />

resource management. The late Charly<br />

McTee, who served as TWA’s general<br />

manager then, called him and asked him to<br />

join. Klussmann agreed only after determining<br />

that TWA and TPWD had addressed the<br />

differences that prompted the TWA’s creation.<br />

“I checked with Charly and I checked with TPWD,”<br />

Klussmann said. “I wanted to be sure that we would be<br />

working together not against each other. Wildlife wouldn’t<br />

have benefited if we were all at cross purposes.”<br />

The answers he received greenlighted his involvement. He got<br />

busy. He has served on TWA’s Executive Committee for more than 15<br />

years and as the PAC Committee Chairman for decades.<br />

“Although our PAC is relatively small, it is effective because TWA is<br />

respected in Austin,” Klussmann said. “Through the years, we have<br />

built a reputation for working for the good of wildlife and habitat—<br />

and doing what we say. Legislators appreciate straight shooters.”<br />

He has also been instrumental in TWA’s education efforts including<br />

the Texas Youth Hunting Program (TYHP) and Learning Across New<br />

Dimensions in Science (L.A.N.D.S.). In fact, the proposal that led to<br />

the creation of TYHP was written at a meeting hosted on his ranch.<br />

“I kept harassing Bob Cook [former TPWD Wildlife Division<br />

Director] telling him that we weren’t doing enough to get young<br />

people involved in hunting,” Klussmann said. “One day he turned to<br />

me and said, ‘Quit bitching, Wallace, and get me a proposal.’”<br />

Klussmann convened a meeting at his ranch. The attendees<br />

generated a proposal that led to TPWD committing $90,000 to hire<br />

the first executive director of what grew into TYHP. After two years, it<br />

became a position jointly funded by TPWD and TWA.<br />

“Of all the things I’ve done in my retirement, the creation of<br />

TYHP has been the most satisfying,” Klussmann said. “We’re not<br />

only giving young people an opportunity to harvest an animal,<br />

we’re giving them a full-blown educational experience that<br />

impacts their families.”<br />

96