EXBERLINER Issue 163, September 2017

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

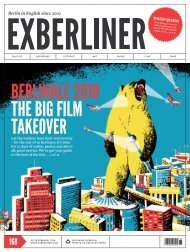

ELECTION <strong>2017</strong><br />

Where’s<br />

the German<br />

Corbyn?<br />

While the charismatic likes of Jeremy<br />

and Bernie have led left-wing surges<br />

in Britain and the US, the German<br />

left still hasn’t been able to come up<br />

with a credible alternative to Merkel.<br />

Ben Knight talked to members of Die<br />

Linke and the SPD to find out why.<br />

Illustration by<br />

Florian Sänger<br />

Angela Merkel is gliding to a fourth<br />

term in office like a big, comfortable,<br />

pragmatically helmed ship.<br />

Of course, the Alternative for Germany<br />

(AfD) will pee into the water and likely<br />

make a smell in the Bundestag, but they<br />

won’t take over Germany.<br />

But what about the left? The G20<br />

protests in Hamburg in July showed<br />

that there’s all kinds of anti-capitalist<br />

rage in Germany, just as the anti-TTIP<br />

protests before them showed there was<br />

a healthy distrust of global neo-liberalism.<br />

So how come none of that is visible<br />

in the opinion polls? The Left party<br />

(Die Linke) is still polling at 10 percent,<br />

and the Social Democratic Party<br />

(SPD) – despite a jolt in January when<br />

European Parliament President Martin<br />

Schulz was named candidate – is back<br />

to trailing Merkel’s CDU by at least 12<br />

percentage points. Why? Why were the<br />

British Labour and US Democrats able<br />

to put forward charismatic leaders like<br />

Corbyn and Sanders, while the Germans<br />

are unable to do the same?<br />

Some would say that the German<br />

left got its Corbyn/Sanders moment a<br />

few years ago, when Oskar Lafontaine,<br />

Gerhard Schröder’s finance minister,<br />

deserted the Social Democrats in 1999,<br />

railed against Schröder’s neo-liberal<br />

social reforms and eventually helped<br />

found Die Linke in 2007. You could call<br />

it the Lafontaine inoculation.<br />

“Lafontaine was a similarly charismatic<br />

figure to Sanders in the US or Corbyn<br />

in Britain. Social Democracy split itself<br />

to the left back then,” says Matthias Micus,<br />

a political scientist at the Institute<br />

for Democracy Research in Göttingen<br />

who has written about the stagnation of<br />

the SPD. “A leftist opposition within the<br />

party doesn’t exist today because it left<br />

the party and joined Die Linke.”<br />

Gero Neugebauer, a political scientist<br />

at Berlin’s Free University who has<br />

written about both the SPD and Die<br />

Linke, would go a lot further back than<br />

Lafontaine. “We just have a different<br />

party tradition here,” he says. Here’s the<br />

short version: the SPD was originally a<br />

collection of different socialist groups<br />

that coalesced in the 19th century before<br />

fragmenting again after World War<br />

I, when various outright radical communist<br />

parties branched off from the<br />

stem of Social Democracy. As a result,<br />

whereas the Democrats and the Labour<br />

Party like to keep their domestic rows<br />

internal (partly because the first-pastthe-post<br />

electoral system doesn’t favour<br />

coalitions), a difference among leftists<br />

in Germany often leads to a new party.<br />

The result of this, paradoxically, is<br />

that political parties here have to be<br />

more ready to compromise with each<br />

other if they want to get into power. All<br />

German governments are coalitions, no<br />

party ever gets to do whatever it wants,<br />

and everyone has to decide beforehand<br />

whom they’d consider bedding in with.<br />

Die Linke and the Greens would be fine<br />

forming a coalition with the SPD; the<br />

CDU would prefer the FDP but wouldn’t<br />

mind the Greens; the Greens would prefer<br />

the SPD but wouldn’t mind the CDU.<br />

The SPD, so far, has shown itself willing<br />

to ally towards the centre, but can’t yet<br />

bring itself to team up with Die Linke.<br />

That affects the political culture,<br />

even for radical parties, and how<br />

people vote. “It just works differently<br />

in Germany,” says Stefan Liebich, Die<br />

Linke’s MP for Pankow, Prenzlauer<br />

Berg and Weißensee. “Voters know<br />

that we have a coalition system, and<br />

they want a coalition system. Even our<br />

own voters know that when we are in<br />

power, we make compromises.”<br />

Die Linke holds many of the same<br />

positions as Corbyn’s Labour Party<br />

– more nationalised industries and a<br />

welfare system not based on punishing<br />

unemployed people, for example<br />

– but, while Germany also suffers<br />

from growing inequality and poverty,<br />

the economic conditions have never<br />

been bad enough to spark outright<br />

outrage. “Germany came out of the<br />

financial crisis very well,” Micus points<br />

12<br />

<strong>EXBERLINER</strong> <strong>163</strong>